Discrimination against traditionally less privileged social groups has been a part of the American legal profession for much of its early existence. In the first half of the twentieth century, attention was drawn to the discriminatory experiences of Jewish and other white ethnic men (Reference AuerbachAuerbach 1976; Reference CarlinCarlin 1966; Reference HornblassHornblass 1993; Reference LadinskyLadinsky 1963; Reference SmigelSmigel 1969). This discrimination lasted well into the 1970s (Reference Heinz and LaumannHeinz & Laumann 1982), but more recent work suggests that discrimination against Jewish men is largely over (Reference HeinzHeinz et al. 2005). However, concern remains about the experiences of women and racial minorities within the legal profession.

Even though women and minorities now enter America's largest law firms in growing numbers, relatively few are retained through the first decade of practice to join these firms as partners. Women today are roughly equal to men among entering associates in large firms, but they constitute only about 17 percent of partners. African and Hispanic Americans each form about 5 percent of entering associates, but neither group forms more than 1 percent of partners. So neither women nor minorities are well integrated into America's largest and most elite law firms. White males still make up more than 80 percent of the partners in these “white shoe” firms (compare Reference SmigelSmigel 1969 with Reference HeinzHeinz et al. 2005). The ratio of African American associates to partners is so big that Reference SanderSander (2006) calls it a “racial paradox.” We know more about the slightly longer-term experiences of women than about the more recent experiences of minorities, but the experiences in large law firms of women and minorities bear notable similarities and can help us understand the fate of both groups as more institutionally predictable than paradoxical. Therefore we use the literature on women's experiences within the legal profession as a way of understanding the experiences of racial and ethnic minorities, which is the primary focus of this article. Based on our findings, we conclude that institutional discrimination may be a better guide than human capital theory to understanding the experiences of minorities within the legal profession.

Gender As Precursor

Women have mounted recent major challenges to the privileged demography of large firm practice, first gaining entrance to law schools and then large firms in growing numbers over the last half of the twentieth century (Reference EpsteinEpstein 1981; Reference Hagan and KayHagan & Kay 1995). Despite these gains, theoretical and ideological resistance to women persists, and this resistance anticipates formidable barriers to the entry and advancement of minority lawyers. Reference BeckerBecker's human capital theory (1964, Reference Becker1985, Reference Becker1991) is an important academic account of resistance to both women and minority lawyers.

The emphasis of Becker's theory is on the efficient development of human capital. His gender theory is grounded in the assumption that women lawyers' capitalization is compromised by a split in their specialized commitments to the spheres of work and family. Women are thus assumed to invest less and to be less committed to their legal careers because they also invest heavily in their families. The deficit caused by split-sphere specialization is assumed to grow over time and also become a source of “stereotype” or “statistical discrimination” along the partnership track, as partners form decisions based on exaggerated assumptions about the work/family split of women associates. However, workplace efficiency has priority over discrimination in Becker's theory, and he concludes that “exploitation is largely a separate issue from efficiency in the division of labor by gender” (1991:4).

Gendered human capital assumptions about specialization choice and work commitment are challenged by empirical research (Reference Kay and GormanKay & Gorman 2008). Recent research finds that although women lawyers fear the consequences of having children for their occupational careers (Reference HaganHagan & Kay 2007), they nonetheless still are “opting in” to the practice of law in numbers similar to men (Reference PercheskiPercheski 2008). Neither research on women generally (Reference Bielby and BielbyBielby & Bielby 1989) nor research on women lawyers specifically (Reference Hagan and KayHagan & Kay 1995) indicates that women differ significantly from men in their long-term commitment to their careers. Young women leave law firms in greater numbers than men and they do not yet attain partnerships in equal proportion to men (Reference Beckman and PhillipsBeckman & Phillips 2005; Reference Hull and NelsonHull & Nelson 2000; Reference KayKay 1997; Reference Kay and HaganKay & Hagan 1998, Reference Kay1999), but these numbers are still changing and there is little evidence that gender differences in outcomes result from the free and efficient choices of women to opt out of their investments and commitments to the legal profession.

Yet human capital theory remains a strong intellectual current in law firm thinking about gender, and as already noted, this theory also influences the logic of law firm thinking about race.

Race As Successor

Racial and ethnic minorities have only recently gained entrance in notable numbers to large firms, and their lower levels of advancement to partnership relative to entry suggest that today they experience an even more skeptical reception than women. To explain this, Beckerian human capital theory substitutes an emphasis on racial differences in legal learning for the emphasis on gender differences in family/work specialization. Thus in this human capital race theory of law firms, hiring preferences linked to affirmative actionFootnote 1 and resulting lowered requirements of academic achievement replace personal family preferences as the root causal force. Human capital theory asserts that as a result of affirmative action policies young minority lawyers who are hired by large U.S. law firms arrive with a human capital intellectual deficit.

Like the response to specialization decisions of young women, lower law school grades of minority law students entering firm practice are thought to be portentous. Human capital theory assumes that partners will socialize and mentor only those associates they presume to be most intellectually gifted. Again, as in the response to gendered specialization differences, cumulative decisions based on early assumptions about differences in ability and achievement are assumed to produce significant disparities in legal experience and rewards. But as in the case of gender, this form of “stereotype” or “statistical” discrimination is not the root concern—the root cause is assumed to be academic accomplishment, which is taken as a key measure of performance and merit. Hence proponents of the human capital merit theory often oppose affirmative action policies, claiming they negatively affect those they are meant to assist (Reference SanderSander 2004, Reference Sander2006; Reference ThernstromThernstrom 1995).

A Human Capital Merit Theory of the “Racial Paradox”

This extension of the logic of Beckerian human capital theory from gender to race in law firms and its policy implications is notably illustrated in Reference SanderSander's (2006) recent and highly publicized law review article. Sander's primary focus is on what he calls “the racial paradox of the corporate law firm”: namely, that so many minority lawyers enter law firms but leave without becoming partners. Sander's work is unusual because it uses empirical data from a unique national study of young lawyers to connect a theory of law school affirmative action policies with law firm preferential hiring practices. But it is even more unusual because Sander's human capital theoretical approach and reported findings about the connection between law schools (2004) and firms (2006) have attracted the attention of mainstream media, including both the Wall Street Journal (Reference HechingerHechinger 2004) and the New York Times (Reference LiptakLiptak 2005, Reference Liptak2006). Sander concludes from his research that a “merit” -based version of what we have called Beckerian human capital theory, focusing on the determining impact of earlier law school performance and measured by academic achievement, plays an important role in the later differential retention of African American and white lawyers who enter law firms. He confidently concludes that “the ‘merit’ theory is not only intuitively logical; it also fits every piece of the data” (Reference SanderSander 2006:1818; emphasis added).

Why, Sander begins by asking, are African Americans overrepresented as entering associates at large law firms but paradoxically underrepresented among these firm's new partners? He responds, “I think the most plausible explanation of this paradox is that the use of large preferences by firms leads to disparities in expectations and performance that ultimately hurt the intended beneficiaries of those preferences” (Reference SanderSander 2006:1759). What Sander regards as a later performance gap linked to preferential hiring is inferred from earlier career differences in law school grades. Sander is clear about the meaning attached to law school grades and their role in law practice. In short, grades matter. The importance firms attach to grades is rational, so far as we can tell from the data, both for the short-term skills of associates and for long-term qualities related to success at the firm. “The much lower grades that result from aggressive racial preferences would therefore logically pose a substantial handicap for minorities entering large firms” (Reference SanderSander 2006:1795).

Sander concludes that this “handicap” in grades is further linked to a pattern of “benign neglect” in the responses of partners to African American associates. The racial merit performance gap is a source of “shunning” by partners who decline to socialize with and mentor African American associates based on their not being “up to the job.” Sander explicitly calls such treatment “benign neglect.” This is presumably an inevitable product of human capital merit and performance differences and therefore a benign “stereotype discrimination” rather than malign “overt” or “active discrimination” (Reference SanderSander 2006:1821). The implication is that large observed disparities in practice performance and merit following from disparities in earlier law school grades make subsequent partner discrimination a form of benign stereotyping. However, Sander does not actually find or report large observed racial/ethnic disparities in performance inside firms (2006).

Sander also attempts to explain why minorities are underrepresented as partners. He argues that minorities are aware of this “stereotype discrimination,” as seen in a lack of mentoring by partners and assignment of challenging work on cases. As a result, many minority associates decide to leave large firms early in their careers, when they are still marketable. This results in fewer minorities going up for and therefore attaining partner status.

Linking the Theoretical to the Empirical

Sander's work is not merely theoretical—it is also empirical. He presents data from several sources to assess his approach. Yet as explicit as Sander's theory is about the role of performance and merit (as measured by earlier law school grades) in explaining the racial paradox of corporate law firms, Sander analyzes neither the combined roles of grades and/or partner social contact and mentoring, nor the assumed differences in performance/merit inside firms, in explaining the paradoxical attrition/retention disparity between African American and white associates in large firms.

Instead, Sander gives the largest amount of his empirical attention to the racial difference in law school grades of associates in the large law firms, followed by a focus on African American/white within-firm experiences, which reveal no large observed differences in performance/merit. In his analyses of firm experiences, Sander conducts a series of bivariate analyses comparing racial differences in a variety of areas including hours worked, number of cases lawyers worked on, and responsibilities on cases. He finds no significant racial differences. He does find significant racial differences in mentoring and plans to leave the firm, with African American associates more likely to report a desire for more mentoring, less informal interaction with partners, and plans to leave large firms within a year. Sander then closes his argument with comparisons of doubtful relevance between male/female and African American/white firm outcomes, as well as large- and small-firm outcomes for African Americans. He uses these empirical results to support his human capital–based theory of stereotype discrimination.

Sander then links the empirical analyses to a policy recommendation of eliminating affirmative action policies by encouraging African American law students to enter less elite law schools and smaller firms, where he argues they could avoid harmful stereotype discrimination and achieve better outcomes.

Sander makes his case for reversing affirmative action policies by describing a set of outcomes he attributes to performance and merit differences, which he in turn links to earlier grades in law school and infers but does not measurably observe inside law firms:

The set of problems that plausibly stem from the aggressive use of racial preferences by law firms are therefore considerable: the frustration and sense of failure they foster among minority associates; the reinforcement of negative stereotypes among majority associates and partners; the likely crippling of human capital development among many of the most able young minority attorneys; substantial economic costs and inefficiencies at the firms themselves; and, of course, the failure of the underlying goal of this whole process – the integration of elite firms at the partnership level. It would be hard to imagine a more counterproductive policy (Reference SanderSander 2006:1820–1).

In short, Sander's policy conclusion is that performance-based merit differences in law school grades play a preparatory and merit-based prognostic role in driving a stereotyping process that undermines the subsequent careers of young African American associates in firms. Therefore, firms should eliminate their affirmative action policies and minority lawyers should go to smaller, less elite firms.

Reference Coleman and GulatiColeman and Gulati (2006), two minority former corporate firm associates and current law professors, accurately anticipated the public attention Sander's article would receive, noting that

Sander's prior work on affirmative action received extensive attention in the national press and, given this article is a provocative extension of that prior work, we suspect Racial Paradox will as well. That means that Sander's article will be one of the few pieces of academic work that actually gets read and taken seriously by those outside the academy. To the extent there is material in his article that will be understood as empirical confirmation of the lack of qualification of black students, the article imposes a high cost on those who need no additional obstacles placed before them (Reference Coleman and GulatiColeman & Gulati 2006:1826).

Coleman and Gulati therefore lament that Sander's work has gone unchallenged by other researchers, saying, “the effect of Sander's study will hopefully be a series of serious follow-up empirical studies into the causes of black attorneys' attrition from large firms” (Reference Coleman and GulatiColeman & Gulati 2006:1827), but also concluding that “we fear that Sander's hypothesis about grades and merit being the root cause of the racial paradox, as opposed to stereotyping, will fill the vacuum for a significant period of time” (Reference Coleman and GulatiColeman & Gulati 2006:1837).

Coleman and Gulati are right about the failure of timely follow-up research to address the role hypothesized by Sander of law school grades—as an enduring measure of performance and merit, including within firms, and/or in relation to partner social contact and mentoring—in explaining the paradoxical attrition/retention disparity in large American firms. Sander also underestimates just how dissatisfied young African American associates are with their experiences in large law firms and overestimates the effect of grades on their experiences.

An Institutional Discrimination Theory of “the Racial Paradox”

Despite the success of affirmative action policies in opening entry-level associate positions for minorities in firms (Reference KalevKalev et al. 2006; Reference SanderSander 2006; Reference SimpsonSimpson 1996), there is also a growing suspicion about more subtle but nonetheless explicit discriminatory practices that are institutionally restricting partner contact and mentoring and lead to high rates of minority departures from law firms and larger corporate America (Reference FormanForman 2003; Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins & Gulati 1996; Reference Thomas and WetlauferD. Thomas & Wetlaufer 1997). While Sander locates merit and performance differences dating to at least law school as the root causes of the “racial paradox” of high rates of minority lawyer departures from firms, institutional discrimination theory provides a more proximate, specific, and parsimonious explanation that makes the racially elevated departures rates not only nonparadoxical but also institutionally predictable.

Partner contact and mentoring is increasingly recognized as a key process and source of dissatisfaction and departures from law firms (Reference Dinovitzer and GarthDinovitzer & Garth 2007), especially for African American lawyers (Reference HigginsHiggins 2000; Reference Holder and VauxHolder & Vaux 1998). In contrast with human capital theory, an institutional discrimination theory suggests that disparity in social contacts with partners and mentoring experiences with partners, rather than disparities in merit and performance, can explain the “paradox” of high rates of minority lawyers' dissatisfaction and departures after being hired into large law firms. If demonstrated to occur, this discrimination in partner contact and mentoring net of merit and performance would make racial/ethnic differences in attrition easily understandable. Given the reduced institutional investment of firms in human capital transmission to minority associates through mentoring, and given a subsequent declining return to minority associates (i.e., on their prior investment in the reputational capital of the law degrees they have already received) in the form of new skills, it would simply be institutionally predictable rather than paradoxical for these minority associates to leave firms in search of better career opportunities.

It is important to further emphasize just how essential mentoring by partners can be in law, as well as other occupational settings. Partner contact and mentoring is a key way of transmitting knowledge and demonstrating the firm's investment and long-term valuing of recruited workers (Reference ThomasK. Thomas et al. 1998). Partner mentorship further provides sponsorship and visibility and may thereby improve prospects for advancement (Reference ThomasD. Thomas 2001). Partner mentors can also provide access to challenging work assignments that can demonstrate the potential of an individual and provide opportunities for growth (Reference ChanenChanen 2006). Partner mentors may also help mentees if they are treated unfairly and provide emotional support in times of stress as well as feelings of acceptance, friendship, and support (Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins & Gulati 1996).

Access to partners and mentoring may be of particular importance in large law firms. According to Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins and Gulati (1996), mentoring is the “royal jelly” of law firms because it builds social skills and contacts as well as legal knowledge. In addition, because many law firms do not have formal departments and work is organized informally, the presence of mentors is key to gaining social access to these groups and the challenging work associated with them (Reference ChanenChanen 2006; Reference JenkinsJenkins 2001).

Research confirms the concern that racial/ethnic minorities are less likely to be mentored (Reference DavilaDavila 1987; Reference NicolsonNicolson 2006; Reference SimpsonSimpson 1996; Reference ThomasD. Thomas 2001; Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins & Gulati 1996). This lack of mentoring is not because of a lack of interest on the part of minorities. In an IBM task force study, Asian, African American, and Native American spokespersons identified networking and mentoring as major concerns among their constituencies. The Hispanic task force identified recruitment and employee development as its primary concerns (Reference ThomasD. Thomas 2004). Within the field of law, the picture is not better. Almost half of the women lawyers studied by Reference SimpsonSimpson (1996) reported that they did not receive the training and challenging cases needed to develop their legal skills. Similarly a study by the American Bar Association of minority women lawyers found that 67.3 percent desired more and better mentoring by senior attorneys (Reference ChanenChanen 2006:36).

Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins and Gulati (1996) conducted an in-depth qualitative study of African American associates in large law firms. They maintain that racial/ethnic differences in treatment may be systemic within large law firms. They argue that while the “superstar” associates of any ethnicity will receive mentoring and training, racial/ethnic differences emerge when the “average” associate, the bulk of the cohort, is considered. They maintain that “average” whites are more likely to be mentored then “average” African Americans. Once African Americans realize they are not receiving the training needed to become partner, they decide to leave earlier in the process, while they still have some market value. The authors go on to argue that firms can do this because there are a limited number of partnerships available and so they are not adversely affected if preference is given to mediocre whites instead of African Americans because the entire group cannot become partner (Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins & Gulati 1996).

In contrast, Reference SanderSander (2006) argues that African American associates are less likely to be mentored because of their differences in human capital. If Sander's human capital–based argument is accurate, then one would expect mentoring and training to matter less in explaining disparities in retention outcomes once “merit” is controlled for. If Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins and Gulati (1996) and institutional discrimination theory are correct, one would expect mentoring to continue to impact attrition even when “merit” is controlled for.

In summary, Sander argues that affirmative action preferences are the source of merit and performance differences in recruitment that lead to stereotype discrimination in offers of mentoring, retention, and advancement. The alternative position of institutional discrimination theory, as presented in the work of Reference Wilkins and GulatiWilkins and Gulati (1996), is that actually affirmative action programs have not yet advanced far enough into law firm practices and instead simply have pushed disparate racial treatment further into the institutional employment experience, without basis in merit and performance differences that persist into the workplace from law school. The institutional discrimination hypothesis is that disparities in contact and mentoring, apart from disparities in merit and performance, account for differential retention and advancement.

Part of the logic of affirmative action policies is to foresee and mitigate the occurrence of institutional discrimination at stages beyond access to education and employment. When institutional discrimination occurs, its effect is predictable rather than paradoxical. If institutional discrimination occurs in partner contact and mentoring, differential retention is not paradoxical. It is this debate between stereotype and institutional discrimination that we address in our analyses. We find, using the same data Sander considered, that institutional discrimination is a better predictor of minority attrition.

A National Study of Young Lawyers

The After the JD (AJD) study is the centerpiece of Sander's article. The AJD study is the focus of his research because it includes a national oversampling of young minority and nonminority lawyers in large American law firms, and because the mail-back portion of the survey includes information about law school grades, mentoring, early work experiences, and perceptions, as well as plans to leave large firms and dissatisfaction with early practice experiences in these firms.

AJD is a national longitudinal survey based on an approximate 10 percent sample of American law school graduates who became lawyers in 2000 and had been in practice for two to three years (Reference DinovitzerDinovitzer et al. 2004). The stratification of the sample is by region and size of the new lawyer population in 2000. The sample includes all four of the largest legal markets with more than 2,000 new lawyers—Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, DC; five of the nine large markets with between 750 and 2,000 new lawyers—Boston, Atlanta, Houston, Minneapolis, and San Francisco; and nine smaller markets.

This mail-back survey began in May 2002, with nonrespondents followed up by mail and telephone. Of the original sample members who were located and who met the criteria for inclusion in the study, 71 percent responded to either the mail questionnaire or the telephone interview, for a total of 4,538 valid responses. The mail portion of the survey used a longer instrument that uniquely detailed measures of grades and in-firm practice experiences. A total of 2,609 respondents, or 57.5 percent of the sample, completed the longer form.

Reference SanderSander (2006) restricted his analysis of associates' plans to leave firms and work satisfaction to the mail portion of the survey of respondents in firms with more than 100 lawyers, while Reference Dinovitzer and GarthDinovitzer and Garth (2007) used a missing data imputation approach to include the phone survey respondents in an analysis that also included measures of law school grades, firm experiences, and work satisfaction in the full sample of lawyers.

While the latter study does not indicate that the outcome of using the missing data imputation approach would involve different results than analysis of the reduced sample, we use the reduced mail portion of the survey to make our results more easily comparable to Sander's findings. Restricting our analysis to cases in which there was observed and complete measurement also better lends itself to a matched cases methodology that we apply. Our analysis is thus based on responses from 321 lawyers with complete data in firms with 100 or more lawyers.

Methodology, Merit, and Mentoring

We first present cross-tabulations of race/ethnicity by key variables in the human capital and institutional discrimination perspectives on race and law firms, including law school grades, early firm performance, partner contact and mentoring experiences, minority firm presence and perceptions, plans to leave the firm in the next year, and job satisfaction. We next present reduced-form weighted logistic and least-squares regressions of our two key outcome variables—plans to leave the firm and job satisfaction—on background demographic characteristics (including race/ethnicity) and variables (law school grades and performance in the firm) that are emphasized but untested in Reference SanderSander's (2006) human capital merit and performance theory of the racial paradox of retention and job satisfaction.Footnote 2 We then turn to an alternative set of regressions that first introduce the institutional discrimination measures of partner contact and mentoring experiences that we argue better explain disparities in retention and job satisfaction, and then we simultaneously introduce in-firm performance measures and minority presence and perceptions of firms, law school grades, and racial/ethnic interaction effects involving perceived discrimination in firms.

We are especially concerned that we rigorously assess the alternative institutional discrimination theory of partner contact and mentoring that we argue makes the racial disparity in retention and job satisfaction institutionally predictable rather than paradoxical. Ideally, lawyers might be randomly assigned to receive or not receive partner contact and mentoring in an experimental design. However, law firms are not experimental laboratories. Propensity scoring techniques are increasingly used to simulate randomized experiments with nonexperimental survey data (e.g., Reference GanglGangl 2006; Reference HardingHarding 2003; Reference LundquistLundquist 2004). Such techniques statistically control for selection bias and allow for more rigorous statements about the potential causal relationship between independent and dependent variables. Yet propensity score matching can result in its own problems, including a loss of cases that introduces its own alternative biases. We use a “full matching” approach, which allows us to retain all cases (Reference Stuart and GreenStuart & Green 2008), and we compare these results with ordinary regression findings.

So in addition to presenting the weighted logistic and least-squares regression results described above, we present results based on propensity scoring with full matching through the program MatchIt. This software establishes our partner contact and mentoring variables (as nearly as possible) as “treatment” variables whose effects are not confounded by other observed variables (Reference HoHo et al. 2004, Reference Ho2007; Reference Stuart and GreenStuart & Green 2008). Eliminating selection bias is especially important in these analyses because many of the variables that may be related to partner contact and mentoring are also associated with job satisfaction and retention. By using propensity scoring with full matching, we can provide a more rigorous and unbiased assessment without losing valuable cases of the association between partner contact and mentoring with retention and job satisfaction.

The key partner contact and mentoring items in the AJD survey ask respondents if they join partners for meals and if they desire more and/or better mentoring by partners. In the MatchIt analyses that supplement the regression results, respondents answering that they join partners for meals and do not desire more and/or better mentoring are considered to have received the “treatment,” while those answering in the alternative are considered “comparison” or “control” group members. Specific scores are assigned to treatment and comparison group members based on a propensity analysis using the independent variables included in the final full regression models. The propensity scores are then used to match treatment and comparison cases.

In full matching, the measured distance is minimized on the predictor variables in the propensity scoring analysis for the matched comparison and treatment cases. Each matched set can have single or multiple treated and control comparison cases. Each comparison case is assigned a weight based on level of similarity to the treatment case (treated cases receive a weight of 1). These weights are then used in regular statistical analyses such as weighted regression (Reference HoHo et al. 2004, Reference Ho2007; Reference Stuart and GreenStuart & Green 2008). All cases are included and, as noted earlier, the amount of bias is usually less than achieved with regular propensity scoring (Reference Stuart and GreenStuart & Green 2008).

The resulting adequacy of the matching can be evaluated with an examination of the standardized biases of the propensity scores calculated for each of the predictor variables used in the matching (Reference Stuart and GreenStuart & Green 2008). Standardized bias is defined as the absolute value of the weighted difference in the means of the matched samples divided by the standard deviation in the full group of respondents. In our analysis, all these residual scores are 0.25 or lower. Reference HoHo et al. (2007:220; see also Reference Stuart and GreenStuart & Green 2008) conclude that “the .25 standard deviation figure, although not a universal constant of nature, is the most common recommendation in the literature.”

Plans to leave one's current position and overall job satisfaction are the two outcome variables examined in our analyses. Planning to leave is a dummy variable coded one if the respondents indicate they expect to leave their large firm position within a year. Overall job satisfaction is a composite measure ranging from one to seven, indicating the average of each respondent's reported satisfaction about issues of recognition, responsibility, performance evaluation process, and value of work. The 17 items included in this composite load well as a scale and have a Cronbach α score of 0.866. Descriptive information about all variables included in our models is presented in the Appendix.

The matching variables, which are also included in the regression analyses, consist of a variety of demographic characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and number of children. In addition, law school merit variables such as law school prestige, self-reported law school grades, participation in law review, and moot court are analyzed. Variables that considered one's merit or performance within the law firm itself are also included, such as whether lawyers took lead or routine roles on cases and number of billable hours. Minority presence and perception within law firms are measured by percentage of minorities within the firm and perceived discrimination. The Appendix contains a full description of these variables as well.

Explaining the Racial Paradox

Cross-tabulations of the race/ethnicity of associates with key variables in Table 1 indicate that white associates consistently differ from minority group associates in large firms. Thus the reports of law school grade point averages (GPA) confirm the influence of affirmative action based racial/ethnic hiring preferences emphasized in the human capital merit performance theory. While approximately half of white associates (49.1 percent) in large firms report average marks between 3.5 and 4.0, about one fourth of African American (23.3 percent) and less than one-third (28.6 percent) of Hispanic associates report receiving these top-tier grades. This difference is especially noteworthy given the finding that minorities are more likely to attend top 20 law schools (60.0 percent of African Americans and 57.1 percent of Hispanics vs. 38.5 percent of whites), which on average give higher grades. However, it is still unclear what role these law school credentials play in lawyer retention and satisfaction.

Table 1. Cross-Tabulation of Categorical Demographic Characteristics, Contact/Mentoring, Law School Credentials, and Plans to Leave Law Firm by Race/Ethnicity Among Lawyers in Large U.S. Law Firms

a Unweighted Chi Square=6.484, with 4 degrees of freedom and p=0.166.

b Unweighted Chi Square=15.341, with 4 degrees of freedom and p=0.004.

c Unweighted Chi Square=10.836, with 4 degrees of freedom and p=0.028.

d Unweighted Chi Square=34.934, with 12 degrees of freedom and p=0.000.

e Unweighted Chi Square=12.199, with 8 degrees of freedom and p=0.143.

f Unweighted Chi Square=20.014, with 4 degrees of freedom and p=0.000.

Turning to the institutional discrimination theory of contact and mentoring, there is a similarly large difference in partner contacts and mentoring for African American and white associates. More than half of the white associates in large firms report joining partners for meals (54.4 percent), while just more than one-quarter of African American (26.7 percent) but more than half of the Hispanic associates (57.1 percent) do so. Once more, less than half of the white associates (47.3 percent) desire more and/or better mentoring by partners, compared to more than two-thirds of African American (70.0 percent) and Hispanic (71.4 percent) associates. Both theories predict resulting disparities in outcomes such as plans to leave the firms and work satisfaction. So it is perhaps unsurprising that about one-fourth of white associates (23.0 percent) plan to leave in the next year, while in contrast half of African American (50.0 percent) and Hispanic (53.6 percent) associates are so inclined.

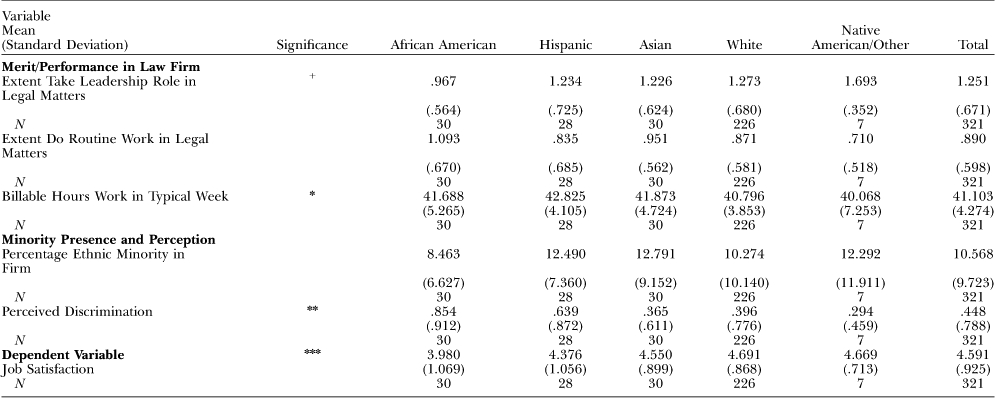

Table 2 presents further bivariate comparisons for relevant continuous variables. Several measures of in-firm merit and performance reveal much smaller differences than are reflected in law school grades between groups. White associates in large firms score slightly higher (1.273) than African American (0.967) associates and about the same as Hispanic (1.234) associates on a four-level measure of taking leadership on legal matters (alpha=0.767) versus doing routine legal work. Of course, this could reflect differences in work assignments rather than initiative. Meanwhile, African American (41.688) and Hispanic (42.825) associates score slightly higher than white associates (40.796) in hours billed per week. This could, in part, be due to the large number of minority lawyers in the four major cities, where lawyers work more hours on average. There is no dramatic or consistent difference in the institutional discrimination measure of representation of minorities in the firm by race/ethnicity of the associates, yet there is a notable difference in perceptions of discrimination in these large firms, with African Americans scoring highest (0.854) and Hispanics next highest (0.639) on a four-point scale on which whites score lowest (0.396). Finally, African American associates score lowest (3.980) on a 17-item scale of work satisfaction (alpha=0.866), while Hispanic (4.376) associates report higher satisfaction than African American associates but lower satisfaction than white (4.691) associates.

Table 2. Cross-Tabulation of Continuous Demographic Characteristics, Mentoring, Law School Credentials, and Plans to Leave Law Firm by Race/Ethnicity Among Lawyers in Private Law Firmsa

a p<0.1

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001.

Reference SanderSander (2006) used bivariate results like some of those just presented to make a case that the lower law school grades of minority associates can account for what he regards as a racial paradox: namely, that minority associates plan to leave law firms soon after they are recruited into them. His reasoning is that lower law school grades are a merit-based predictor of poorer performance in early law firm careers and that this performance difference leads to minority associates leaving these firms. Yet Sander does not take the next step of demonstrating that there is a bivariate relationship between lower law school grades or performance in early law firm careers and plans to leave firms, or that such relationships can in multivariate terms account for the more frequent “paradoxical” reports of African American and Hispanic compared with white associates' plans to leave these firms.

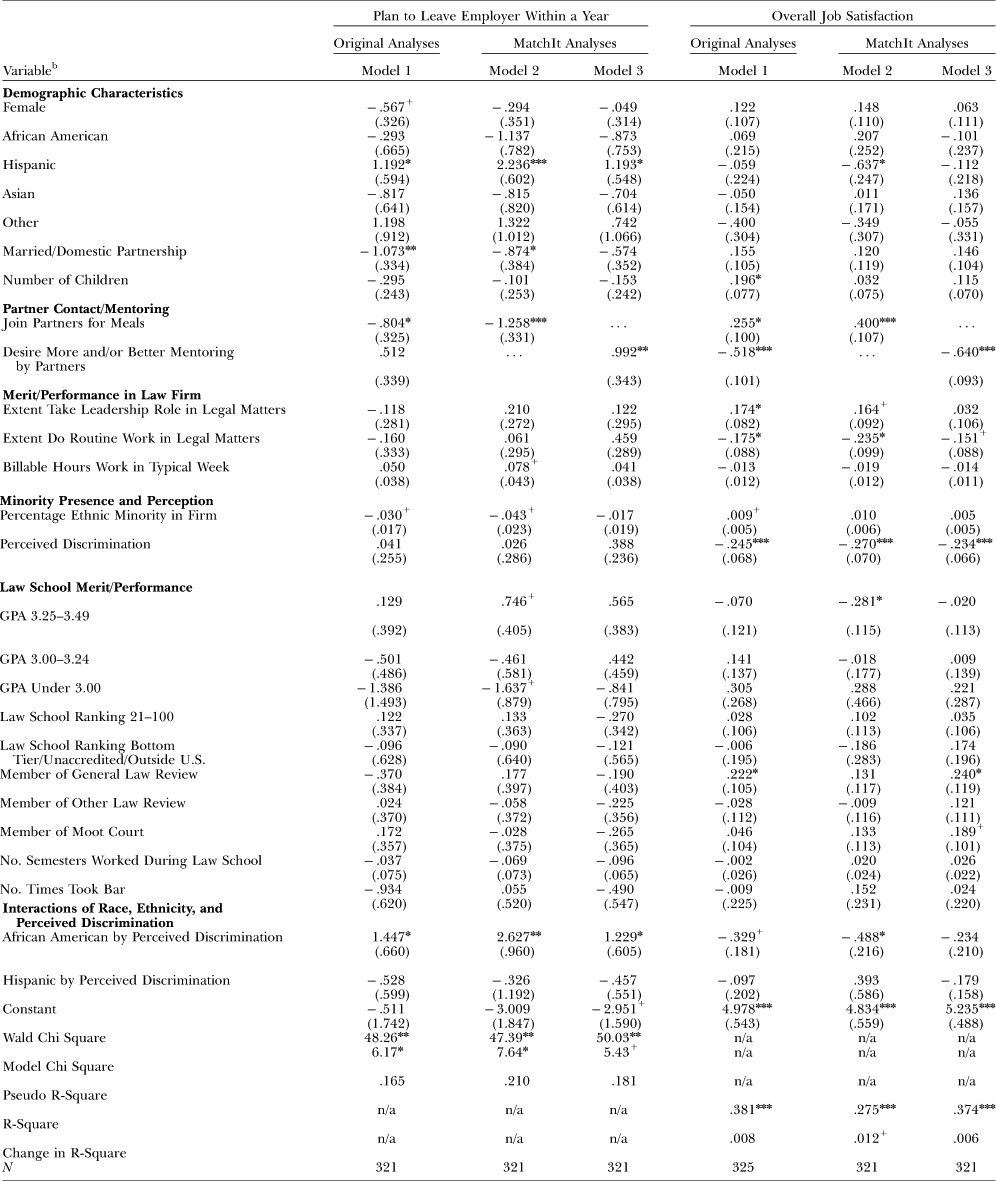

This is important because the results presented in Table 3 question basic assumptions of this racial/ethnic human capital theory about early career plans in large law firms. The left half of Table 3 presents logistic regression models of associates' plans to leave large firms within a year. In Model 1, both African American (b=1.177, p<0.05) and Hispanic (b=0.992, p<0.05) associates significantly more often report plans to leave. However, Model 2 indicates that neither law school grades nor measures of in-firm performance significantly increase these departure plans, and inclusion of these human capital merit and performance measures actually slightly increase rather than reduce the racial/ethnic coefficients (to 1.273 and 1.023, respectively).

Table 3. Regression of Plans to Leave Employer Within a Year and Overall Job Satisfaction by Demographic Characteristics Among Lawyers in Large Law Firms (Weighted Analyses)a

a p<0.1

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001. Listwise deletion used.

b The reference categories are as follows: (1) Gender: Female; (2) Race: White, Not Hispanic; (3) Marital Status: Not Married; (4) GPA: 3.50–4.00.

The righthand side of Table 3 addresses a further aspect of the human capital argument. Reference SanderSander (2006:1797) concludes on the basis of a single measure of job satisfaction—“How satisfied are you with your decision to become a lawyer?”—that minority respondents are not significantly dissatisfied with their work. Yet Model 1 on the right side of Table 3 presents results based on a 17-item measure (alpha=0.866) indicating that African American associates (although perhaps not Hispanic associates) are significantly more dissatisfied (b=−0.610, p<0.01) with their work than white associates. This disparity is slightly decreased (b=−0.516, p<0.05) but is still significant in Model 2 when the merit and performance measures of the quality of legal matters on which the associates are working are added to the equation.

The institutional discrimination theory argues that the above racial paradox of plans to leave and dissatisfaction is actually predictable. Table 4 introduces the measures emphasized by an institutional discrimination theory in a combination of ordinary logistic and least-squares regression models, as well as in models based on the matching analyses using treatment and comparison groups. We focus on the matching analyses because they provide the most rigorous means of isolating the effects of partner contacts and mentoring while holding extraneous sources of heterogeneity such as merit and performance constant. However, it is notable that the regression and matching results yield parallel substantive conclusions.

Table 4. Conventional and Matched Regression of Plans to Leave Employer Within a Year and Overall Job Satisfaction by Demographic Characteristics and Main Mentoring Variables Among Lawyers in Large Law Firms (Weighted Analyses)a

a p<0.1

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001. Listwise deletion used.

b The reference categories are as follows: (1) Gender: Female; (2) Race: White, Not Hispanic; (3) Marital Status: Not Married; (4) Join Senior Attorneys/Partner for Meals: No; (5) Desire More and/or Better Mentoring: No.

Recall that MatchIt identifies effects for “treatment” variables by making the “treatment” and “comparison” groups of respondents as similar as possible on the variables identified in the Appendix. When this is done, the measures of partner contact (b=−1.135 and 0.414, p<0.01) and mentoring (b=1.098 and −0.696, p<0.01 and 0.001) respectively still have highly significant effects on both plans to leave and work dissatisfaction. These separately measured treatment effects are likely capturing predictably overlapping partner contact and partner mentoring effects.

The results of the models estimated in Table 4 further indicate that in each case these measured treatment effects of partner contact and mentoring predictably decrease by about half and below statistical significance the effects seen previously in Table 3 of African American associates' plans to leave large firms (to b=0.626 and 0.562, p>0.05). Partner contact and mentoring are clearly salient factors in explaining associates' thoughts about seeking alternative employment and in the more frequent plans of African American associates to do so.

The results in Table 4 are more mixed for Hispanic associates' plans to leave and with regard to both African American and Hispanic work dissatisfaction. Controlling the treatment effect of joining partners for meals actually increases the disparity in Hispanic associates' (b=1.643, p<0.01) plans to leave while also revealing a differential in work dissatisfaction (b=−0.508, p<0.05); in contrast, controlling the treatment effect of the desire for more and better mentoring by partners reduces the differential in plans to leave among Hispanics (b=0.827, p>0.05) slightly below statistical significance. Controlling the treatment effect of joining partners for meals reduces the disparity and significance of African American associates' (b=−0.389, p>0.05) work dissatisfaction, but controlling the desire for more and better mentoring by partners leaves the tendency of African American associates to be more dissatisfied largely unchanged (b=−0.510, p<0.001). Hispanic associates do not appear more dissatisfied than other associates before or after (b=−0.247, p>0.05) the introduction of the treatment effect of desire for more and better partner mentoring.

Table 5 includes not only the separate estimations of the partner contact and mentoring treatment effects, but also further includes in the equations all the variables that are involved in the matching of cases, as well as interaction terms representing non-additive effects of African American and Hispanic associates' perceptions of discrimination. The latter racial interactions are of primary importance in this table. In three of the four matching equations, the African American perceived discrimination interactions are statistically significant, and in all four matching equations the African American disparity in plans to leave the large firms and in work dissatisfaction are now explained in the sense of being reduced below statistical significance. Thus when disparities in partner contact and mentoring experiences and race-specific perceptions of discrimination are statistically controlled, the more frequent plans of African American associates to leave large firms and to be dissatisfied in their work are largely explained.

Table 5. Regression of Plans to Leave Employer Within a Year and Overall Job Satisfaction by Demographic Characteristics, Mentoring Variables, Law School Credentials, and Interaction Terms Among Lawyers in Large Law Firms (Weighted Analyses)a

a p<0.1

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001. Listwise deletion used.

b The reference categories are as follows: (1) Gender: Female; (2) Race: White, Not Hispanic; (3) Marital Status: Not Married; (4) Join Senior Attorneys/Partner for Meals: No; (5) Desire More and/or Better Mentoring: No; (6) GPA: 3.50–4.00; (7) U.S. News & World Report 2003 Law School Ranking: Top 20; (8) Member of General Law Review: No; (9) Member of Other Law Review: No; (10) Member of Moot Court: No.

The implications of perceived discrimination for Hispanic associates are again less clear than for African American associates. Perceived discrimination has significant main effects in both work dissatisfaction models, but the Hispanic associate results by perceived discrimination interactions are nonsignificant.

Revolving-Door Law Firms

African American associates in large elite U.S. law firms do not perceive their experiences in these firms as “benign.” There is instead predictability to their plans to leave these firms shortly after their recruitment. Like women before them, many African American associates find the institutional experience of large law firms, and more specifically their reduced partner contact and mentorship in these firms, to be adverse. It is these more specific and proximate experiences, rather than the merits of their more distant academic training in law school or their more recent performance at work in these firms, that results in the plans of African American associates to seek alternative employment. By this evidence, a focus on merit and performance issues as a means of explaining a racial paradox in rates of leaving large firms is a form of false stereotyping that misleadingly disguises more “active” institutionalized discrimination experiences. These findings support an institutional discrimination theory of partner contact and mentoring and cast doubt on a human capital–based theory of merit and performance in explaining high rates of African American departures from large U.S. law firms.

Prior research in a variety of subfields (e.g., Reference HaganHagan et al. 2005; Reference Portes and RumbautPortes & Rumbaut 2001) has reported a gradient in African and Hispanic American experiences of discrimination, with African American experiences being more acute in practice and perception. Similarly, although our research finds that both African and Hispanic American associates are more likely than others to plan to leave the large firms into which they are recruited, this disparity is stronger for African than for Hispanic American associates; and while African American associates also are significantly more likely than others to express work dissatisfaction in large law firms, this is not so clearly true of Hispanic associates. In general, the pattern of our results is more consistently predictable for young African than Hispanic American lawyers.

Our findings suggest reason to question the role of a racial human capital theory of merit and performance in guiding the professional development of law firms. We have raised basic questions about the findings reported in Reference SanderSander's (2006) highly publicized research on the racial paradox of law firm retention of African American associates. This research infers a pattern of benign stereotype discrimination with roots in racial differences in law school grades and their assumed impact on racial differences in plans to leave law firms. However, it is important to critically assess the relative role of law school grades—as an enduring measure and predictor of performance and merit, including within firms, and/or in relation to partner social contact and mentoring—in explaining the paradoxical attrition/retention disparity in large American firms. We have found that partner social contacts and mentoring better account for racial differences in plans to leave large law firms. It is also important to acknowledge and analyze just how dissatisfied young minority associates are with their experiences in large law firms. When these other factors are considered, the results do not support the human capital theory's explanation of racial differences in lawyer retention, while our findings are consistent with institutional discrimination theory.

Our research may have important implications for affirmative action programs and policy. While the burden of effort to integrate American law firms has focused on recruitment of new associates into large firms, our research suggests that problems are not confined to recruitment policies but rather extend to the practices of partners with regard to minority lawyers once they are employed. Our findings suggest an institutionalized pattern of discrimination in which African American associates in particular are less likely to experience the benefits of being socially integrated and mentored by partners. These young lawyers in turn are more likely to perceive discrimination in their institutional experiences in large firms. Affirmative action mandates with regard to partner contact and mentoring of minority associates may be essential to achieve an effective racial integration of the upper reaches of the legal profession. Therefore, this study has practical and professional implications that extend beyond similarly pressing theoretical or empirical questions.

Finally, our research can provide some direction for future research on minority attrition in large law firms. More information is needed on what types of mentoring are most beneficial to minority associates. In addition, gender differences in job satisfaction and attrition among ethnic minorities should be explored. We control for gender in our analyses of plans to leave and overall job satisfaction and find that it does not have a consistent effect (see Table 5). This lack of a finding could be the result of our small sample size of ethnic minorities. Future research should consider if minority women find it even more difficult to develop mentoring relationships and get the experience they need to succeed within large law firms. Research in other fields suggests that minorities who feel social isolation and negative stereotyping underperform (e.g., Reference FoxFox et al. 2009; Reference Walton and CohenWalton & Cohen 2007; Reference Walton and SpencerWalton & Spencer 2009). Future research may want to explore how the lack of mentoring and job satisfaction may influence the performance of minority associates, which may also increase the rate of attrition. Scholars should also consider other variables within firms that may lead to minority dissatisfaction. For example, certain aspects of firm culture may be incompatible with the culture of some ethnic minorities, leading to even more social isolation and a desire to leave the firm. Finally, future studies should explore the extent to which dissatisfied minority associates who plan to leave their current positions in large firms actually leave and where they end up. Such research could provide valuable insight into which policies may decrease experiences of institutional discrimination and increase minority retention in large law firms.

This research was supported by grants from the American Bar Foundation, National Science Foundation (Grant No. SES0115521), Access Group, Law School Admission Council, National Association for Law Placement, National Conference of Bar Examiners, and Open Society Institute. The views and conclusions stated herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of individuals or organizations associated with the After the JD study. Thanks to David Wilkins for helpful comments.

Description of Lawyer Characteristics, Mentoring, and Job Satisfaction Among Lawyers in Large Law Firms

Note: Reference categories are italicized.