In a November 28, 1550, letter to William Cecil, then secretary of state, Protestant divine William Turner demonstrated how intertwined his studies of natural philosophy were with his religious conviction and political maneuvering. After his reformist zeal led to his rejection from consideration for leadership positions at Oriel and Magdalen colleges, Turner feared that he might never find the preferment he sought in England, and he proposed to Cecil that a return to the continent would offer him some consolation. Turner had first left England in early 1541 after marrying in defiance of his diaconal vows, and this sojourn abroad had enabled him to obtain an Italian MD.Footnote 1 If Cecil obliged with funds, Turner wrote, a new tour would enable him to complete a number of writing projects on theology and natural history. Both of these interests, as well as Turner’s careful study of textual transmission, are clearly on display in his request, as was his deep-seated conviction that the Roman Catholic church had corrupted doctrine:

if that i myght haue my pore prebende cu[m]myng to me yearly i will for it correct ye hold [old] newe testament in englishe, and wryt a booke of ye causis of my correctio[n] & changing of the translatio[n]. I will also finishe my great herball & my bookes of fishes stones & metalles, if good sende me lyfe and helthe.Footnote 2

Turner’s play on “old” and “new” was characteristic; more than a decade earlier, he had translated works by Joachim von Watt and Urbanus Regius, and these works’ English titles indicate Turner’s preoccupation with textual corruption: Of ye Olde God & the Newe (1534; STC 25127) and The Olde Learnyng & the Newe (1537; STC 20840). Turner’s exegetical interests in Protestant reform offered a valuable backdrop to his botanical investigations, encouraging him to couple textual analyses and corrections of classical and modern authorities with his own observations of plants. More often than not, on the title pages of his botanical works Turner’s role is identified as a “gatherer,” a figure who locates and assembles disparate information into a cohesive and useful whole. In his magnum opus, a three-part herbal of 1568 that was fully published only after his death, the unpublished third part of Turner’s work is presented as “lately gathered.”Footnote 3

Turner’s combination of observation, correction, and accretive book learning has appealed to modern critical sensibilities, and historians have hailed him as the “Father of British Botany” since the endorsement of that phrase by Benjamin Daydon Jackson in 1877. Turner’s paternal moniker offers a useful framing for understanding how his specific form of rhetorical self-fashioning became naturalized within the history of “author-ized” botanical books. The first named English herbalist carefully and explicitly signaled his use of his contemporaries, particularly continental herbalists, and Turner’s paratexts demonstrate the way that herbals were conceived by their authors as an iterative and intertextual genre even as the medium of the printed book enabled authors to declare their authority as “herbalists” to the world. In both verbal and pictorial content and in codicological form, then, herbals as a genre were embedded within a textual ecosystem that calls singular authorship into question. Later texts build upon the findings of previous ones, and later authors stand to gain by arguing and correcting their predecessors. The herbal genre, in other words, is self-perpetuating, and it was this recursive propagation that made such books particularly attractive to the publishers who stood to profit from their sale.Footnote 4

Turner and Cecil had become acquainted in the employ of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, where Cecil had been Somerset’s secretary and Turner his physician. Through Cecil’s intervention, shortly after the 1550 request, Turner succeeded to the deanery of Wells, but his religious successes were soon extinguished by the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary I in 1553. Turner, like many English reformers, fled to the continent. The hands-on studies of continental plants that Turner’s exiles made possible, coupled with his understanding of English flora, enabled him to overcome the linguistic and biogeographical barriers that had stymied his fellow English natural historians who still subscribed to the works of Dioscorides and Pliny as if they were dogma. By demonstrating his respect for these classical authorities while simultaneously acknowledging that there were limits to the information that modern editions of their works could possess, Turner’s lasting contributions to British botany have as much to do with his understanding of the ways that written texts can often lead the faithful astray as they do with his developing empiricist ethos, a codicological awareness Leah Knight describes as Turner’s “botanical reformation.”Footnote 5 I argue in this chapter that, throughout his careers as a naturalist and as a reformer, Turner strategically deployed print, using the medium to his advantage in both terrestrial and celestial fields to make his authoritative pretentions manifest. As a surrogate for his person, Turner’s printed books could go places that he could not, and they could speak even when their author was in continental exile.

Turner’s desire for authority is most on display in his medical works, where, after becoming a physician in the 1540s, he quickly adopted the domineering authorial posture characteristic of those who recognized that print could be instrumentalized to serve the medical establishment’s larger professional goals. Yet there is also an ambivalence laced throughout Turner’s writing. As he suggests that printed texts can usefully serve as surrogates for their authors, he also displays an increasing concern that the rapid and unauthorized transmission of books in print may lead to an author’s original intentions becoming corrupted. Once made public, copies of a printed book take on a life of their own, and authors are unable to control how others read and receive their message. Authors therefore needed to manage early modern stationers, the makers and distributors of books, with careful rhetoric to try to prevent the stationers’ agency over the printed artifact undermining the authority of authors over their subject matter. Like his continental contemporary Leonard Fuchs, Turner’s authorial self-fashioning responded to his dependency upon stationers by attempting to distinguish himself from those artisans whose skills were integral to his authoritative posturing.

Turner was not alone in his recognition that print could serve as a proxy for an author’s expertise and professional standing. In Chapter 5, I argued that in his 1539 edition of The Great Herball, the grocer-apothecary and printer Thomas Gibson used his address to the reader to reframe that work’s medical stance and support the professionalization of medicine. While the earlier and later editions of The Grete Herball of Peter Treveris and John King had suggested that books like herbals might serve as surrogates for medical practitioners like apothecaries, Gibson eliminated a closing address that recognized the way readers themselves could become practitioners of herbal medicine through study of the natural world. Instead, Gibson’s paratextual materials foreground the Galenic expertise espoused by European physicians, which Gibson later became, and suggest that the most trustworthy medical books should be accompanied by medical doctors’ endorsements or oversight. Thus did early modern physic and early modern bookselling become intertwined, as physicians quickly realized that printed books offered an opportunity for physicians to lay claim to public knowledge about the body. Over the course of his career in print, Turner, who may have known Gibson personally, eventually also came to assert that physicians’ authority allowed them to control the discourses of healing provided by printed books like herbals.

Turner’s authoritative posturing in his books of natural history complicates our understanding of his doctrinal positions because his professional status as a physician eventually required his endorsement of a hierarchy of knowledge that is seemingly at odds with the reformist position of sola scriptura. While, on the one hand, Turner’s botanical writing simply grows to endorse physicians’ traditional approaches to lay readership by assuming doctors’ command over readers’ understanding of their own bodies, reading Turner’s herbals alongside his religious polemics reveals contradictions with his earlier insistence on Christians’ informed but independent judgment in spiritual matters.Footnote 6 What gradually begins to emerge in his botanical writing is evidence of an epistemological collision between Turner’s dual roles as reformer and physician, as his affiliation with the latter group struggled to control an information medium that the former group had masterfully and strategically used to its advantage. Despite (and perhaps because of) this increasing ambivalence about authority, however, Turner’s publications throughout his lifetime display his acute awareness of the ways that print can be deployed strategically to support authorial agendas, and his lasting status as “the father of British botany” shows that, at least in the field of natural history, his efforts were successful.

Others have found similar evidence of Turner’s authorial ambivalence in the religious polemics he wrote attacking the Henrician bishop Stephen Gardiner, The Huntyng & Fyndying out of the Romishe Fox (1543; STC 24353) and The Rescuynge of the Romishe Fox (1545; STC 24355). Erin Katherine Kelly has shown that in these hunting tracts Turner instrumentalized the printed medium as a proxy for his devoted service in order to engage a “canny” posture that facilitated a simultaneous “assertion of status and an expression of utter servility.”Footnote 7 In Turner’s tracts, the publication of printed books are tools for making public the heretofore hidden efforts of Romish predators lurking in the king’s dominion. The narrator’s role as a reluctant hunter forced to seek out Gardiner, the Romish Foxe, aligns with his positioning the tracts as “hounds” dutifully deployed in service of Henry VIII. As Kelly notes, however, “the meanings attached to participants in the hunt, animal or human, change as Turner’s argument requires,” and Turner’s chosen metaphor also enables him to “use[] the hunt to assert his own status, both as a commentator on religious affairs in England and as a potential loyal servant in a truly reformed England.”Footnote 8 Yet the self-effacement is transient; when Turner returns to the hunt as a metaphor a decade later in his 1555 tract The Huntyng of the Romyshe Vuolpe (1555), Kelly says “the carefully calibrated humility that was evident in the earlier two tracts is discarded” in favor of a new declaration of expertise. However, Turner’s appreciation of the role of the printed medium as a vehicle for his self-pretention is still in clear evidence:

I haue for my parte found out these wolues, where as they were so dysgysed, that a man unexpert in thys kynde of hunting, which I do professe, would haue thought that they had been men, and not onely men, but honest men, and no Wolues. I haue in thys my boke shewed you where they be, & who they be.Footnote 9

For Turner, in 1545, printed books are useful largely because they make hidden truths public, but, by 1555, the material form of print is the foundation of an author’s authority to interpret. In both cases, however, the agents that Turner insists are responsible for “thys my boke” are not the stationers who made such works available to readers as publishers, printers, and distributors but the author who wrote its text.

Turner’s attitude towards printed books, and the uses to which they can be put by clever authors, can be seen to shift over the course of his interrelated careers as a physician, divine, and naturalist. This chapter demonstrates how Turner’s three herbals reflect a bibliographic self-consciousness in English botany that was emerging simultaneously with the efforts of English physicians to assert their influence over all elements of medicine. Anonymous bestselling English works like the little Herball as well as The Grete Herball were widely available during Turner’s undergraduate studies at Cambridge, but despite their popularity with readers, Turner claimed that those works offered little of use to professional medical practitioners. It was to remedy what he called the “unlearned cacography” of these texts that Turner was prompted in 1538 to first offer up his own botanical studies in English for the good of the commonweal despite his fellow physicians’ concerns that such an endeavor would make specialized professional knowledge widely available to laypeople.Footnote 10 Historians of botany have largely taken Turner at his word and consequently viewed him simply as a benevolent democratizer of medical information; however, the herbals that Turner wrote after he obtained a medical degree reveal that, like Thomas Gibson and Leonard Fuchs before him, Turner came to develop a mistrust of laypeople’s judgment. The shift in the attitudes of his herbals likewise mirrors the way that Turner’s approach to print changes through his hunting pamphlets: books that were first materially useful because of their wide distribution later become useful as a textual mechanism for asserting authoritative control. In either case, however, stationers profit so long as Turner’s books sell to a willing public. In the wider context of the trade in Renaissance books, then, Turner’s herbals result less from his personal religious zeal or professional ambition than they do from Tudor printers willingly taking advantage of an anticipated market demand.

Turner Reads the Print Marketplace

At the time of writing his 1550 appeal to Cecil, Turner had only just returned to England after a decade of self-imposed exile on the continent that had been necessitated by Turner’s marriage to Jane Alder.Footnote 11 Along with the ecclesiastical charges stemming from this marriage, Turner had also been wanted on charges of heresy for The Hunting & Fyndyng of the Romishe Foxe and The Rescvynge of the Romish Fox. The tracts had been printed in Germany and smuggled into England along with other reformer texts, and the crown, fearing that the pamphlets would fuel Protestant uprisings, had issued a prohibition on July 7, 1546, “[t]o auoide and abolish suche englishe bookes, as conteine pernicious and detestable erroures and heresies” (STC 7809). Along with Tyndale’s and Coverdale’s translations of the New Testament, no one in England

shall receiue have take or kepe in his or their possession, any maner of booke printed or written in the english tongue, which be or shalbe sette forth, in the names of Frith, Tindall, Wicliff, Joy, Roy, Basile, Bale, Barnes, Couerdale, Tourner, Tracy, or by any of them, or any other boke or bokes conteining matter contrary to the kinges maiesties booke, called, A necessary doctrine and erudition for any christian man.Footnote 12

Unaffected by this proclamation were Turner’s Latin works that were less accessible to lay readers, including his botanical tract Libellus de re Herbaria novus in quo Herbarum aliquot nomina greca, latina & anglica habes, vna cum nominibus officinarum (STC 24358), a short quarto published by John Byddell and distributed from his shop at the sign of the Sun on London’s Fleet street in 1538.Footnote 13 This “new booklet concerning herbal matters, in which you have some Greek, Latin and English names of herbs, together with names of medicaments,”Footnote 14 was effectively a simple glossary of 144 plants that included linguistic variants in plant names. Compared even to earlier botanical works like the multiple editions of the little Herball and The Grete Herbal, the practical or medical information contained in Turner’s Libellus was slight. For every Alsine that offered “this is the herb which our women call Chykwede [chickweed] … those who keep small birds shut up in cages refresh them with this when they are off their feed,” there were a dozen Athanasia that stated merely “[this] is called tagetes in Greek, tanacetum in Latin, what the English have called Tansy.”Footnote 15 The work is primarily a multilingual dictionary designed to enable readers to keep botanical signifiers in order as they read other texts. In other words, Libellus is a book that both relies upon and supports the existence of other books.

Turner’s biographers have noted that his fellow exiles on the continent during Henry VIII’s and Mary’s reigns were significant contributors to both his medical and his botanical development. Because universities were major sites for both humanism and medical education, natural historians affiliated with universities on the continent were among the first to interrogate the philology of plant names and to connect these linguistic investigations to their own personal experience with plants.Footnote 16 The first botanical garden was established in Pisa in 1544; a second followed in Padua in 1545. The original purpose of such gardens was to provide an applied education in simples for students as part of their medical education, and after their humanistic instruction at Oxford or Cambridge, many would-be English physicians were granted permission to seek residencies at Italian, Swiss, French, or Dutch universities to further their studies.Footnote 17 During his first exile in the early 1540s, Turner took advantage of his time on the continent to become a doctor of medicine at either Ferrara or Bologna, a degree that Cambridge incorporated upon his return to England in 1547. Such credentials enabled Turner to act as both physician and auxiliary chaplain to his patron, the Earl of Somerset, Lord Protector at Seymour’s residence at Syon.Footnote 18

Turner’s interest in plants as medicaments becomes evident from the preface to Libellus, which displays a mild rebuke to those learned men who refuse to share their knowledge in print. In his 1538 address to the “Candid Reader,” the thirty-year-old Turner explains why he, a “still beardless youth” (imberbem adhuc iuuenem), would attempt to write a herbal when he knows that there are, “in such studies, six hundred other Englishmen who precede me (as they say) on white horses.”Footnote 19 Despite these numerous but nameless would-be English herbalists, however, there remains in 1538 no printed list of English and classical botanical equivalencies like the one Turner himself provides, and he admits that he “thought it best that [he] should try something difficult of this sort rather than let young students who hardly know the names of plants correctly go on in their blindness.”Footnote 20 Such blindness, it seems, Turner himself had experienced as an undergraduate at Cambridge. He would later reminisce in the introduction to his 1568 New Herball that the Libellus was born from his frustration with inadequate instruction as an undergraduate, which could not be remedied by turning to the book market:

euen beyng yet felow of Penbroke [sic] hall in Cambridge/ wher as I could learne neuer one Greke/ nether Latin/ nor English name/ euen amongest the Phisiciones of anye herbe or tre/ suche was the ignorance in simples at that tyme/ and as yet there was no Englishe Herbal but one/ al full of vnlearned cacographees and falselye naminge of herbes/ and as then had nether Fuchsius nether Matthiolus/ nether Tragus written of herbes in Latin.Footnote 21

At least as he reconstructs his motivations in 1538 thirty years later, Turner saw his Libellus as filling a void for scholarly English readers, who had no printed works fit to guide their botanical explorations that had been produced by a native natural historian of plants.Footnote 22 Anonymous works like the little Herball (1525) and The Grete Herball (1526) were increasingly available in new editions, but each offered so little in the way of descriptive information on plant nomenclature, morphology, or localities that they were virtually useless for bridging the gap between the various continental and English terminologies for plants that Turner had identified. Whichever work it was that Turner recognized in his condemnation of the only “vnlearned cacographee” that was available to early English readers, it is clear that he nonetheless saw the enterprise of herbalism (cognoscendis herbis) in England as a nascent scholarship open to those willing to investigate on their own. Throughout Libellus, Turner urges his candid reader to read critically and improve upon his work: “If I am caught blundering (and this is very easy) I will gladly be corrected by men of learning. For I am not too proud and pleased with myself to accept gladly the verdicts of the learned.”Footnote 23

Turner clearly saw the works of continental authors as a crucial aid to plant identification and classification, and their names appear throughout his many volumes of natural history to bolster his arguments or to offer inferior hypotheses that Turner then endeavors to correct. For example, in his later 1548 volume The Names of Herbes, Turner notes that

Stachys semeth to Gesner to be the herbe that we cal in english Ambrose, & I deni not but that it may be a kynde of it. Howe be it I haue sene the true Italian staches, whiche hath narrower and whiter leaues then Ambrose hat. It maye be named in englishe little Horehounde or strayte Horehound.Footnote 24

Because Turner’s first herbal was a gloss or equivalency table of plant names, the text’s nature mostly precluded his citation of other botanists; nonetheless, a few authoritative figures appear in the work’s preliminaries. In 1538, those men esteemed by Turner as sufficiently “learned” included the Parisian physician Jean Ruel and German physician Otto Brunfels, whose works served as excellent exemplars of regionally inflected service to a growing body of natural philosophy. In Libellus’s address to the reader, Turner mentions both men by name, and both also regularly appear in the references of his later botanical writings. The first volume of Otto Brunfels’s three-volume Herbarum vivae eicones was printed by Johannes Schott in Strasburg in 1530, a work that, as its title (“Living Portraits of Plants”) suggests, was chiefly notable for its illustrations by Hans Weiditz, a pupil of Albrecht Dürer. Later volumes followed the publication of this text in 1531–1532 and 1536. Ruel’s translation of Dioscorides’ De materia medica (first printed in Greek by the Aldine Press in 1499) had been published in Paris by Henri Estienne in 1516; by 1551, Turner seems to have owned or to have had access to a copy of one of Ruel’s many editions. Both Ruel and Brunfels frequently appear in Turner’s A New Herball among a group of continental authorities whose printed works “haue greatly promoted the knowledge of herbes by their studies, and haue eche deserued very muche thanke, not only of their owne countrees, but also of all the hole common welth of all Christendome.”Footnote 25 Printed books of botany improved “the hole common welth” through their dissemination, which made what was once individual knowledge widely available, able to be shared in common.Footnote 26 Turner’s investment in others’ printed works was typical of the era, as Brian W. Ogilvie has noted: “published texts [of natural history] were not the end product of the process of natural history research; rather they were themselves employed as tools by naturalists seeking to make sense of their particular experience.”Footnote 27 In other words, later herbals descended from earlier ones, and previously printed botanical books were a crucial location for herbalists’ “gathering” behaviors.

A crucial and distinctive part of Turner’s use of contemporary botanical authorities, however, is his recognition of their provenance. He is particularly attuned to the sources that individual authors used in their translations of classical authorities. For example, in his entry on Nerium in the second volume of his Herball (1562), Turner notes that the seed pod

as it openeth/ sheweth a wollyshe nature lyke an thystel down/ as Ruellius tra[n]slation hath/ it semeth [that] hys greke text had άκάνθινοις παπποις. But my greke text hath ύάκινθίνοις παπποις. And so semeth the old translator to have red/ for he he [sic] translatheth thus: lanam deintus habens similem hyacintho. Yet for all that I lyke Ruelliusses Greke text better then myne for the down is whyte and lyke thestel down/ & nothynge lyke hyacinthus …Footnote 28

Printed Greek works were presumably available to Turner in the libraries of his friends and colleagues during his exiles on the continent between 1540 and 1558, but the availability of such texts in Cambridge in 1538 may have been limited, as only Ruel and Brunfels were mentioned in the text of the Libellus. Later, in the second part of the New Herball, Turner insists that the limited availability of good translations could be mitigated if publishers included the original work along with the vernacular conversion, “for so myght men the better examin theyr translationes.”Footnote 29

Turner notes that including both original and translated texts together would not only benefit plant knowledge by enabling correction but also encourage the spread of self-education, a secular form of the sola scriptura that was consistent with his devotion to religious reform. Turner’s awareness of the limited availability of quality books motivated both his educational and his reform goals, and he insisted that authors themselves were responsible for helping to remedy this bibliographic problem. This pursuit accords well with modern standards of scholarly citation and, I argue, later helped to ensure Turner’s botanical reputation.

Once he obtained his MD, Turner’s reputation was also protected by his role as a physician. As Turner realized that printing made possible a widespread distribution of books, he also recognized an opportunity that could serve his pastoral and botanical interests: the diverging systems of professional and civic authority governing the three medical professions. While physicians were university-trained professionals who were required to complete a Master of Arts degree before even beginning their medical studies, surgeons and apothecaries were educated through a seven-year apprenticeship in accordance with the customs of the City of London. Surgeons were ostensibly required to be conversant in Latin in order to pass their church-mandated licensing examination, yet since this requirement was often waived or inconsistently applied, its lax enforcement provided physicians with a humanistic basis for asserting surgeons’ inferior understanding: they did not know their Latin and were therefore wholly ignorant of the medical tradition. Apothecaries, originally included within the Grocers’ Company, were unable to split off from it until 1617, when their efforts were assisted by a College of Physicians that had a vested interest in the Apothecaries’ pharmacological skills.Footnote 30 Though Turner was never admitted into the select and limited membership of the College of Physicians of London, his boasts of superiority over other medical practitioners were in keeping with the general attitude that the College took towards the subordinate practitioners it had, since 1518, been charged with overseeing.Footnote 31 By the end of the sixteenth century, all three groups of medical practitioners had attempted to use print to their advantage, but physicians’ early strategic deployment of Tudor herbals gave them a head start in the quest for medical authority.

Turner’s attitude towards printed books of English botany in 1538 might have been formed through a relationship to Thomas Gibson, whom I identified in Chapter 5 as the first figure in English botany to introduce an authoritative posture in order to limit the interpretive boundaries of his work. Gibson’s unillustrated third edition of The Great Herball (1539) both removed that work’s Catholic sentiments and added a preface that promoted physicians’ authority over all elements of medical care. A reconsideration of Gibson’s changes to the text sheds additional light on Turner’s early dismissal of the English herbals available for study. While in 1538 he may well have shared with Gibson the latter conviction about the authority of medical doctors, Turner himself was not yet a medical doctor directly invested in the elevation of physicians at the expense of other kinds of authorized medical professionals.Footnote 32 Evidence of just such an attitude is apparent, however, in Turner’s next botanical publication, published after he had become a physician.

The Names of Herbes (1548)

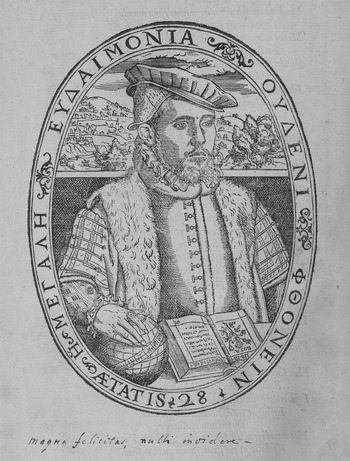

The Names of Herbes in Greke, Latin, Englishe, Duche & Frenche wyth the commune names that Herbaries and Apotecaries vse. Gathered by William Turner was published in 1548 by John Day and William Seres cum gracia & priuilegio and printed by Steven Mierdman. Eventually the holder of the patents for John Ponet’s catechism, the works of Thomas Becon, the Sternhold and Hopkins metrical psalter, and ABC with a Little Catechism, as well as the publisher of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, Day was arguably the most important stationer of his era and had an especially keen eye for saleable works, even early in his career. Day’s willingness to invest in Turner’s The Names of Herbes indicates that he believed there to be a viable market for a new English herbal, particularly one dedicated to the young King Edward VI. Day may have had a personal interest in herbals or simply wanted to flatter those who did, such as his patron William Cecil, who was especially fond of gardens. In his edition of physician William Cunningham’s The Cosmographical Glasse (STC 6119), for which, with Cecil’s aid, Day received a lifetime patent in 1559, Day commissioned a woodcut author portrait of Cunningham reading an illustrated herbal of Dioscorides beside a globe (Figure 7.1), signaling a relationship between cartography and botany that would increasingly figure in defenses of European colonial expansion.Footnote 33 Though Day printed most of his later books for himself, some of his earliest work was produced at the press of Steven Mierdman, an Antwerp printer resident in London between 1548 and 1553. In July 1550, Mierdman received a five-year generic grant of privilege from the king to print books at his own expense, but with the young king’s death, the Protestant Mierdman was forced to flee to Emden, where he died in 1559.Footnote 34

Figure 7.1 Portrait of William Cunningham from The Cosmographical Glasse (1559), sig. A3v.

During the better part of a decade that he spent in Europe during his first exile, Turner had investigated continental vegetation, attempting to reconcile his studies of the works of Pliny and Dioscorides with the new plants he encountered and collating them with his working knowledge of English flora that John Byddell had published as the Libellus in 1538. The Names of Herbes builds on the linguistic equivalencies in the earlier work, adding plant locations where known, as in his entry for Alnus, or alder trees (“it growth by water sydes and in marrishe middowes”).Footnote 35 Most of the work is devoted to reconciling his experience with classical description: “The best Gramen and moste agreying with Dioscoridis description, dyd I see in Germany with other maner of rootes.”Footnote 36 Occasionally, where he feels he has something to add or to correct in the works of authorities, Turner includes updated descriptions of plants that he mentions:

Typha growth in fennes & water sydes amo[n]g the reedes, it hath a blacke thinge Almost at the head of the stalke lyke blacke Veluet. It is called in englishe cattes tayle, or a Reedmace, in Duche Narren Kolb, or Mosz Kolb.Footnote 37

Throughout The Names of Herbes, Turner’s research into nomenclature is diverse and nonjudgmental, much like a modern-day descriptive linguist would produce. He offers names for the herbs of the ancients in a variety of languages, as well as the names that his contemporary apothecaries and “herbarists” actually use: “Seseli massiliense is called in the Poticaies shoppes, siler montanum, it may be called in englishe, siler montayne”; “Pistacia are called of the poticaries Fistica, they may be called in english Fistikes or Festike nuttes”; “Oxycantha is called in englishe as it is named of the poticaries berberes.”Footnote 38 By explaining how “poticaries” identify plants, Turner presumes a reader requesting simples at an apothecaries’ shop, indicating that he expects an audience who engages with apothecaries in their role as public merchants, not necessarily with apothecaries in their role as private healers. Such a feature hearkens back to the “exposycyon of the wordes obscure” feature of The Grete Herball, and Turner’s inclusion of “the Potecaries and Herbaries Latin” in his writings later becomes a central feature of the title page advertising for his larger, three-part herbal.

The distinction between apothecaries as vendors of prepared plants or as healers of patients is crucial to Turner’s larger authoritative goals in The Names of Herbes. In the period between the publication of his first herbal in 1538 and his second herbal in 1548, William Turner became a physician, and Turner’s investment in the medical authority of physicians over other members of the medical professions becomes clear. In the 1548 preface, Turner outlines the provenance of his latest botanical work, explaining that he had finished a Latin version of the text two years previously but had refrained from seeking to have it published after his fellow doctors urged him to provide a more comprehensive guide to English plants. His colleagues suggested instead that he investigate more broadly and, in particular, that he replicate the features of Fuchs’s successful De historia: “they moued me to set out an herbal in Englishe as Fuchsius dyd in latine with the discriptions, fisgures and properties of as many herbes, as I had sene and knewe.”Footnote 39

Yet an illustrated English work like Fuchs’s opus was impossible for Turner, or indeed any author, to produce on his own. As we have seen, an illustrated herbal requires a considerable outlay of capital from a willing printer able to invest in woodcut illustrations that can support an author’s text, as well as the support of craftsmen who can draw and carve them. Turner explains in his preface that he was unable to complete such a compilation at present, though he carefully suggests that he, as the author, is the limiting agent. He simply does not have the time, given his other responsibilities as physician and chaplain to the Lord Protector: “I could make no other answere but that I had no such leasure in this vocation and place that I am nowe in, as is necessary for a ma[n] that shoulde take in hande such an interprise.”Footnote 40 The codicological means by which his “vocation” could find its audience remains unmentioned – booksellers, block-cutters, and printers are nowhere to be seen. Turner’s business was not an issue, however, in his acquiescence to his friends’ other request, that he “at the least to set furth my iudgeme[n]t of the names of so many herbes as I knew whose request I have acco[m]plished, and haue made a little boke, which is no more but a table or regestre of suche bokes as I intende by the grace of God to set furth here after.”Footnote 41 Here, again, Turner leaves unmentioned the role of the publishers whose finances would enable his books to be made and “set furth,” as their agency and capital would undermine his careful maneuvering for political preferment. Characteristically, Turner follows up the account of his accomplishment with a direct request that the Lord Protector provide him with both leisure and a “co[n]venie[n]t place as shall be necessary for suche a purpose,” a request that, as his above-quoted letter to Cecil reveals, Turner felt had still not been adequately satisfied by November 1550.Footnote 42

Before concluding his 1548 preface with another appeal to the benevolence of Lord Seymour, Turner highlights his scholarly deference to the medical authority of classical authors, chiefly Galen, to signal his professional allegiance. In an assertion of his own empirical authority derived from personal experience, Turner hints at a mistrust of apothecaries’ judgment:

And because men should not thynke that I write of it that I neuer sawe, and that Poticaries shoulde be excuselesse when as the ryghte herbes are required of the[m], I haue shewed in what places of Englande, Germany & Italy the herbes growe and maye be had for laboure and money, whereof I declare and teache the names in thys present treates [treatise].Footnote 43

Turner’s botanical knowledge, gained by firsthand experience, is newly strengthened by his professional standing as a physician, which extended his authority over the body. Just as, in 1539, Gibson’s preface to The Great Herbal confirmed the righteousness of doctors’ control over all elements of ministry to the sick, so Turner’s 1548 preface concludes by declaring that the usefulness of his latest herbal will be confirmed by expert physicians: “howe profitable it shall be vnto al the sicke folke of thys Realme, I referre the matter vnto all them whiche are of a ryght iudgeme[n]t in phisicke.”Footnote 44 While in his Libellus of 1538 the naturalist Turner would suffer to be corrected by any “man of learning,” a decade later his work’s success or failure might be properly estimated only by those members of the medical caste in which he is now a member: formally educated physicians.

There are some limits to Turner’s new professional conceit as a doctor, but these are centered on the objects of his botanical observations. Though he is largely confident in his status as an authority, in The Names of Herbes Turner often indicates his unwillingness to pronounce a verdict on a given plant when the evidence is inconclusive: “Bacchar or Baccaris is the herbe (as I thynke) that we cal in english Sage of Hierusalem, but I wyll determine nothynge in thys matter tyl I haue sene further. Let lerned men examine and iudge”; “I heare saye that there is a better kynde of Buglosse founde of late in Spayne, but I haue not seene that kynde as yet”; “Chamaecyparissus is supposed of some men to be the herbe that we cal Lauander cotton, whose opinion as I do not vtterly reiect, yet …”Footnote 45 Such caution has suggested to botanical historians eager to cement Turner’s status as “the Father of British Botany” that he employed the skeptical scientific rigor espoused by modern science more than a century before the founding of the Royal Society. This may be true, but as Turner’s estimations center on a recognition of his own elevated subjectivity as a physician, it also seems clear that he views some kinds of botanical judgments as better than others, depending on the professional status of those who pronounce them. By 1548, then, Turner had internalized what Steven Shapin identifies as a key element in intersubjective trust, using his social and professional status to present to his readers authorized truth claims within printed English works of botany.Footnote 46

Authorizing the Medical Marketplace

Turner’s allusions to the advice of other physicians suggest his increasing bias towards the superior role of the medical establishment in the construction of an updated body of English natural philosophy. While Turner’s desire to discuss his botanical work with fellow physicians was perhaps not surprising, it is remarkable that he claims to have sought out their advice on the particulars of publishing it. As I have argued throughout this book, determining the reading market for a printed edition is the purview of a publisher who functions as a book’s speculative investor. A number of concurrences in Turner’s biography suggest that he was acquainted with at least one physician who was uniquely qualified to evaluate the saleability of his latest botanical work, someone who had recently edited, published, and printed an herbal himself: Thomas Gibson. Though no evidence survives suggesting a direct connection between the two men, biographers have charted several coincidences between Turner and Gibson: both were born in Morpeth and attended Cambridge, where they were noted for their commitment to Protestant reform.Footnote 47 Further, in 1548, both men had works published by the upstart publisher John Day shortly after Day had finally secured his right to retail books within the City. A short tract credited to Gibson, A Breue Cronycle of the Bysshope of Romes blessynge (STC 11842a), was published by Day and sold at his shop at the sign of the Resurrection “a little aboue Holbourne Conduite.”Footnote 48 While such surmises are not demonstrable, the coordination of two Morpeth-born physician-divines seeking publication from the same bookseller suggests that Day may have been particularly sympathetic to physicians’ engagement with print.

Day’s early biography provides additional hints that he was acquainted with printed medical texts, as well as those who used them. As a younger man, Day was apprenticed or otherwise in service to the physician Thomas Raynald, a printer of engraved pictures who was responsible for publishing the midwifery manual The Byrth of Mankynd (1540, STC 21153).Footnote 49 Raynald had been in London at least since 1540, when a deposition was made to the City on August 17 of that year by “Thomas Mannyng, John Borrell and John Day late servants to Thomas Reynoldes printer late dwelling at Hallywell nere unto London,” which asserted that a series of goods were Raynald’s own.Footnote 50 Among the jackets, gowns, and cloaks were a number of books, including works by Vincentius,Footnote 51 as well as two herbals, suggesting Raynald’s interest in medical books.Footnote 52 His effects also include a series of engraving plates for printing male and female anatomical figures with paste-in illustrated flaps, demonstrating Raynald’s awareness of how print could be used as a surrogate or supplement to a physician’s medical training. The midwifery volumes that Raynald published likewise indicate his cognizance that much-needed books of physic were still missing from the marketplace. If John Day had been Raynald’s apprentice or otherwise worked for him before he started printing and publishing on his own, Day would have directly observed Raynald’s navigation of the London market for medical books.

Day is now best known as the publisher of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, but his early skill at observation and his extraordinary ability to recognize opportunity were instrumental in his later success. As no London company yet had authority over the craft of printing, it could be practiced by anyone, but, as I explained in Chapter 2, goods could be retailed in London only by those who were free of the city. At the time he was working for Raynald, Day was a foren, an Englishman who had not been born in London, which restricted his employment and freedoms within the City limits until he could obtain the status of freeman. Raynald’s standing in London was unclear, but as the deposition of 1540 does not identify him with any City company, it is likely that he primarily earned his living as a physician, a profession that did not take apprentices.Footnote 53

Day began printing in 1546, the same year that the company of Stringers (bowstringers) were permitted by the City to admit twenty redemptioners to their company. These new members gained their admission by paying a fee and, once done, became freemen, eligible to buy and sell retail goods as well as practice their craft. Though the names of those who were made free by redemption by the Stringers in 1546 are unknown, it is almost certain that Day was one of them.Footnote 54 He was “translated” (transferred) to the Stationers’ Company in 1550. By 1553, Day had received patents for a number of the most profitable books in England. These patents would eventually help Day become one of the wealthiest stationers of his era, but more than a decade before that he was in service to the physician Thomas Raynald at the same time that Raynald published the first (and possibly also the second) edition of The Byrth of Mankynd.Footnote 55 Raynald’s publication was the first English book to feature engraved illustrations, and the expense and complexity of providing these high-quality images testify to Raynald’s belief in their value.Footnote 56 The volume’s preliminaries highlighted that most of the listed remedies for ailments were Greek or Latin terms that would be unfamiliar to most lay readers, highlighting the necessity of an English work of linguistic glosses for plants that Turner’s The Names of Herbs later provided.Footnote 57 In bringing The Names of Herbes to Day to publish, then, Turner may have found himself a particularly sympathetic investor.

By the time that the first part of Turner’s A New Herball appeared in print in 1551, he had become fully persuaded that physicians were expert witnesses over the medical domain. He also had become something of a botanical evangelical, claiming that the study of plants, being tied to medicine, was of the highest order of knowledge ordained for men by God. Turner writes that “[a]lthough … there be many noble and excellent artes & sciences, … yet is there none among them all, whych is so openy com[m]ended by the verdit of any holy writer in the Bible, as is [the] knowlege of plantes, herbes, and trees, and of Phisick.”Footnote 58 Turner’s musings throughout his preface use biblical and apocryphal exegesis to define the value of botanical study and demonstrate the elevated role of the physician, who learns of the fruits of the earth and uses that knowledge to heal, and to teach, others. The physician’s status as an intellectual authority is central to these tasks, because “The knowledge of the Phisicio[n] setteth vp hys heade, and maketh [the] noble to wondre.”Footnote 59 While apothecaries might temper medical mixtures together, their efforts are merely mechanical deployments of the wonders of God’s creation: “his [the apothecary’s] workes bringe nothinge to perfecyon, but from the lorde commeth furth helth into all the broade worlde.”Footnote 60 By contrast, the physicians’ appreciation of the causes of illness through their investment in the Galenic systems that underlay healing better recognize the complexity that underwrites creation. Turner thus ultimately urges his readers to place their trust in God – and in God’s most hallowed professional servant: “My sonne in thy syckenes fayle not, but pray vnto God: for he shall heale [thee]: leue of synne, shewe straight handes, and clenge thy harte from all synne. And then afterwarde gyue place vnto the Phiscion, as to him: whom god hath ordened.”Footnote 61

This attitude of deference to physicians’ theoretical knowledge is not unique to English books but is typical of the larger herbal genre; the German Herbarius features a large woodcut on its title page depicting physician sages such as Galen and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) dictating their wisdom to the text’s engrossed author, whom the preface identifies as a “great master” of medicine in his own right.Footnote 62 The German Herbarius’ preface similarly highlights the way that the work is designed to demonstrate “the wonderful works of God, and His benevolence in providing natural remedies for all the ailments of mankind.”Footnote 63 Such Christian devotion became conventional, particularly as Renaissance herbal authors needed to navigate increasing numbers of works of classical and Arabic authorities. What is unique to Turner’s approach, however, is the way that a traditional deference to medical authority becomes explicitly religious in its commandments, synching the usual generic pieties with a clear and defined expectation for readers that conveniently aligns with the larger goals of the English medical profession: “gyue place vnto the Phiscion, as to him: whom god hath ordened.”

As Turner continues his sermon on the superiority of physic, the celestial privilege afforded to doctors comes to situate ever more terrestrial concerns. After he notes that the hallowed status accorded medicine is unique among the subjects available for study, he shifts his attention from religious and historical attitudes to medicine’s superior subject matter of the human form. Because “mannis body is more precious then all other creatures,” “so is Phisick more noble and more worthy to be set by, then all other sciences.” Turner argues that those who bring works of physic into being should be celebrated, for “howe great a benefit doth he vnto the commo[n] welth that with great study and labor promoteteth, & helpeth men to the knowledge of Phisick.”Footnote 64 The printed books of physic that can be read and studied are implicit in Turner’s formulation, as are the efforts of the authoring physician who makes it possible for physic to be studied to the betterment of the commonwealth. The implicit nature of the book form becomes even more explicit as Turner returns to a theme familiar from his Libellus of 1538. More physicians should apply themselves to authoring herbals, Turner suggests, because England’s national honor is at stake:

There haue bene in England, and there are now also certain learned men: whych haue as muche knowledge in herbes, yea, and more then diuerse Italianes and Germanes, whyche haue set furth in prynte Herballes and bokes of simples. I mean of Doctor Clement, Doctor Wendy, and Doctor Owen, Doctor Wotton, & maister Falconer. Yet hath none of al these, set furth any thyng, ether to the generall profit of hole Christendome in latin, & to the honor of thys realme, nether in Englysh to the proper profit of their naturall countre.Footnote 65

Turner supplies a rationale for these men’s refusals to write about plants, surmising that they do not want to risk their learned reputations by setting forth works in print in which others may find fault. Instead, Turner’s own botanical efforts will serve to remedy the gap left by his fellow physicians, who are too fearful of public reproach to risk their status. Here, then, as in Turner’s hunting tracts, the printed book is imagined to be a surrogate for its author, who may be made vulnerable by virtue of his works’ publicity. By exaggerating the hazard to his own reputation, Turner is thus able to elevate his status as the first Englishman to author a printed herbal in any language. Turner’s enthusiasm for plants can then be associated with the same nationalistic fervor that governed his reformist investment in the nascent Church of England:

I therfore darker in name, and farr vnder these men in knowledge, for the loue that I beare vnto my countre, and at the commandeme[n]t of your grace my lord and maister, I haue set one part of a great herball more boldly then wysely and with more ieopardy of my name then with profite to my purse, as I knowe by dyuerse other bokes, whych I haue set out before this tyme, both in English and in Latin.Footnote 66

As he thus supplicates in offering his work to Somerset, Turner’s status as servant to the Lord Protector (and, by extension, to the king himself) paradoxically enhances the authority over all aspects of medicine that he claims for his profession. Turner’s technique of what Erin Katherine Kelly called his “canny posture” in Romysh Foxe is once again deployed to authorizing effect as he positions himself as a gracious and knowledgeable public servant.

Turner’s claim to authority derives from his dissemination of specialized knowledge to an otherwise-ignorant public, but this role immediately opens him up to another criticism, one that he is particularly eager to preempt: Why would a trained physician make his profession’s expert understanding available to a wider audience by offering it not only in print but also in the vernacular? When physic manuals were written exclusively in Greek or Latin, knowledge of their contents required a modicum of humanistic training, but English works could be read by anyone literate in a populace that was ever increasing. Printing and selling books about medicine would therefore render physic public and able to be practiced by everyone, a deeply unsettling prospect, because it leads, according to Turner, to murder:

for now (say they) euery man with out any study of necessary artes vnto the knowledge of Phisick, will become a Phisician, to the hynderau[n]ce and minishyng of the study of liberall artes, and the tonges, & to the hurte of the comenwelth. Whilse by occasyon of thys boke euery man, nay euery old wyfe will presume not without the mordre of many, to practyse Phissick.Footnote 67

Turner’s surmised objection, that knowledge of physic printed in the vernacular would cause public harm, reaffirms his assertion of medicine’s scholarly primacy, begging the question of why anyone would bother with the study of “liberall artes” at all if not to practice medicine.

In his response to this anticipated criticism, Turner returns to his familiar theme of bettering the English public through education, an ethos that his biographer Whitney R. D. Jones calls Turner’s “Commonwealth thinking.”Footnote 68 Such views involve “a completely traditional approach to such matters as due degree, gentility (with its cognate obligation of liberality), vocation, and economic morality” alongside a redistribution of Catholic wealth in the service of “poor relief and education.”Footnote 69 Turner’s English herbal of remedies is thus a public service, one which ensures that physicians, those with access to the most authoritative, text-based information about functional medicaments, provide their medical inferiors with a comprehensive system of instruction that recognizes both their inherent intellectual limitations and the social circumstances in which all medical players (including physicians) are employed. Turner’s defense of printed physic is so extraordinary that it is worth repeating in full:

I make thys answer, by a questyon, how many surgianes and apothecaries are there in England, which can vnderstande Plini in latin or Galene and Dioscorides, where as they wryte ether in greke or translated into latin, of the names descriptions and natures of herbes? And when as they haue no latin to come by the knowledge of herbes: whether all the Phisicians of England (sauyng very few) committ not [the] knowledge of herbes vnto the potecaries or no, as the potecaries do to the olde wyues, that gather herbes, & to the grossers, whylse they send all their receytes vnto the potecary, not beyng present their to se, whether the potecary putteth all that shuld be in to the receyt or no? Then when as if the potecari for lack of knowledge of the latin tong, is ignorant in herbes: and putteth ether many a good ma[n] by ignorance in ieopardy of his life, or marreth good medicines to the great dishonestie both of the Phisician and of Goddes worthy creatures, the herbes and the medicines: when as by hauyng an herball in English all these euelles myght be auoyded: whether were it better, that many men shuld be killed, or the herball shulde be set out in Englysh? The same reason might also be made of surgeons, whether it were better [that] they should kyll men for lack of knowledge of herbes or [that] an herball shuld be set out vnto them in English, whiche for the most part vnderstand no latin at all, sauying such as no latin eares can abyde?Footnote 70

While surgeons remedy injuries such as wounds and broken bones themselves, offering their patients healing medicaments where needed, physicians refuse such mechanic practices, instead prescribing their remedies for illnesses that patients need to take to an apothecary to be filled. As apothecaries rarely gathered their own plants but were often beholden to grocers and “old wyues, that gather herbes,” the success or failure of both the surgeon and the physician’s enterprise was entirely dependent on the accuracy of the plant knowledge of these inferiors all the way down the line. If England was to avoid mass death through medical error, according to Turner, medical practitioners needed a standard means to check up on the accuracy of the old wives’ plant knowledge, and apothecaries needed a printed resource to guide their ministrations. Though Turner’s New Herball is directed as much to these kinds of practitioners as it is to his fellow physicians, his massive tome nonetheless serves to benefit the physicians’ authoritative interests. Once printed, Turner’s herbal could become a surrogate for physicians’ control over their medical subjects, a mirror of ecclesiastical dominance over an underinformed laity.

Turner’s mixing of religious and medical language continued through the remainder of his career, and by the third and final volume of his herbal, published posthumously in 1568, he did not let his physician peers off lightly. In order to oversee the efforts of surgeons and apothecaries (as well as those herb gatherers and old wives that they oversaw), he claims that physicians themselves needed to become conversant in simples, for “w[ith]out [the] knowledge wherof they can not deuly exercise their office and vocation where vnto they are called / for howe can he be a good artificer that neither knoweth the names of hys toles / nether the toles themselfes when he seeth.”Footnote 71 As for Turner’s nonmedical or lay readers engaged in a process of self-healing, a right that English men and women could claim through Henry VIII’s “Quacks’ Charter,”Footnote 72 Turner advises that they should not attempt medicine at all without first seeking the advice of a qualified professional. The herbal’s companion volume, The Booke of the Natures of Triacles (1568, STC 24360), admonishes, “I giue warning to all men and women that wil vse these medicines, that they take the[m] not in rashly and vnaduisedly, without the aduise and counsell of a learned phisition, who may tell them, whether they be agreeing for their natures and complexions and diseases or no.”Footnote 73

A large part of Turner’s defense of vernacular medical texts comes from his approval of those who self-educate only when they recognize the authority of others who claimed oversight over particular knowledge domains. The printed book therefore provided opportunities for authors to become teachers, an extension of pastoral practice. Turner’s 1568 herbal was dedicated to “the right worshipfull Felowship and Companye of Surgiones of the citye of London chefely / and to all other that practyse Surgery within England,” not only because its contents most readily benefited that group of medical practitioners but because this group was particularly committed to a botanical education.Footnote 74 Such approval emerges even in his address to Elizabeth, where Turner promotes the value of a humanistic education by conspicuously complementing the queen’s Latin instruction, rendering his appeal for Elizabeth’s patronage oddly patronizing:

when as it pleased your grace to speake Latin vnto me: for althought I haue both in England / low and highe Germanye / and other places of my longe traueil and pilgrimage / neuer spake with any noble or gentle woman / that spake so wel and so much congrue fine & pure Latin / as your grace did vnto me so longe ago: sence whiche tyme howe muche and wounderfullye ye haue proceded in the knowledge of the Latin tonge / and also profited in the Greke / Frenche and Italian tonges and other also …Footnote 75

Turner’s paradoxical status as Elizabeth’s medically authoritative subject is made possible through his authoring a text that, though dedicated to her majesty, is really intended for the good of her commonwealth: “my good will considered / and the profit that may come to all youre subiects by it / it is not so small as my aduersaries paraduenture will esteem it.”Footnote 76

Turner’s endorsement of the broader benefits of education appears to have been genuinely meant and was consistent throughout his career. This “Commonwealth thinking,” then, helps Turner overcome the potential collision between his sympathies as a reformer and his professional identity as a physician, and it is his bibliographic awareness that makes such a synthesis possible. Throughout his works, Turner gives his support for the widest possible dissemination of both religious and secular knowledge in print, downplaying concerns that the specialized knowledge of the professional classes is dangerous when known outside of its authorized sphere. Instead, the printed book, when properly authorized and disseminated widely, may be used for the spiritual and the physical benefits of all Englishmen.

Making Physic Public

As Turner’s endorsement of physicians’ biblical and social authority leads him to honor the writings of his professional forebears, he becomes vulnerable to the familiar insecurity of early modern authors concerned their would-be patrons might believe the slander of envious rivals. Turner particularly fears that he might be charged with an offense that could render his attempt at obtaining patronage null and void: “for some of them will saye / seynge that I graunte that I haue gathered this booke of so many writers / that I offer vnto you an heape of other mennis laboures / and nothinge of myne owne / and that I goo about to make me frendes with other mennis trauayles.”Footnote 77 In other words, Turner worries that the very bookishness of his botanical scholarship puts him at risk for charges of plagiarism. Citing others – particularly living others – in his work might be viewed as theft, and Turner seems aware of the criticism that Christian Egenolff had leveled at Leonhart Fuchs a few decades earlier: despite Fuchs’s pretense of authorship, his own knowledge is, to a publisher like Egenolff, just the stuff of other books. If so, anyone could engage in this craft of synthesis, particularly when it comes to depicting God’s creation. To preemptively defend himself and claim the text of his herbal as his own work, Turner cites both the authority of classical authors and the early modern custom of commonplacing. His apt defense makes traditional use of the metaphor of honeybees’ collection of nectar and returns to his own title page identification as a “gatherer”:

To whom I aunswere / that if the honye that the bees gather out of so manye floure of herbes / shrubbes / and trees / that are growing in other mennis medowes / feldes and closes: maye iustelye be called the bees honye: and Plinies boke de naturali historia maye be called his booke / allthough he haue gathered it oute of so manye good writers whom he vouchesaueth to name in the beginninge of his work: So maye I call it that I haue learned and gathered of manye good autoures not without great laboure and payne my booke …Footnote 78

By more than a century, Turner’s claim of the “laboure and payne” he took in 1568 in composing, correcting, and compiling his herbal prefigures John Locke’s 1690 assertion in the Two Treatises of Government (Wing L2766) that “every Man has a Property in his own Person … the Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his.”Footnote 79 Through his efforts to “learn” and “gather,” Turner has synthesized what knowledge has come before him and supplemented it with his own. Through his labor in making his book, Turner thereby fulfills the physicians’ ordained role and served the commonweal by making it possible for the secrets of God’s creation to be publicly known.

Turner’s defense in his preface contains two parts. First, he echoes the same defense used by the Frankfurt printer Christian Egenolff when Egenolff was charged with the violation of Johannes Schott’s privilege for copying the woodcuts of the physician Otto Brunfels’s Herbarum vivae eicones, which I discussed in Chapter 1. Because his subject matter is the nature of God’s creation, Turner insists, only God can rightfully claim authority over information about plants. Second, Turner claims that even though he did examine the printed works of his predecessors, he took pains not to rely too heavily on the work of any one of them. As Leah Knight notes, Turner’s strategy is paradoxical, resting “the defense of his work as his own on the fact that it is compiled from so very many authors. By his logic, a little plagiarism is a dangerous thing, but a lot is authorship.”Footnote 80 Turner mentions Fuchs, Tragus,Footnote 81 Dodoens, and Mattioli by name, noting that he relied on their writings less to acquire new information than to confirm his own experience.Footnote 82 By virtue of what Locke later understands as the right of property through labor, Turner’s gathering from others’ works, coupled as it is with his own experiential evaluation, serves to enable him to claim of his book that “I haue something of myne owne to present and geue vnto your highness … Wherefore it may please your graces gentelnes to take these my labours in good worthe.”Footnote 83 Because Turner’s labors include the correction of others’ works, then, the availability of other printed herbals does not diminish but actually reinforces his claims to authority over English botany.Footnote 84

The physician William Turner’s reputation as a herbalist and a reformer remains unmarred by any charges of “plagiarism” or unoriginality that might otherwise accompany modern scholarly interpretations of his conspicuous borrowing from the works of his predecessors. That was not the case for the barber-surgeon John Gerard, however, who, in writing his herbal just half a century later, has been subject to a very different notion of the responsibilities of authorship. Despite his considerable civic prominence during his lifetime and his unremarkable use of the conventions of the herbal genre, historians have largely labeled Gerard’s intellectual contributions to botany illegitimate. Even as Turner’s humanistic endeavors to compare the works of the ancients with his own experience were celebrated, Gerard’s authority as a textual “gatherer” was rejected. The following chapter examines the provenance of Gerard’s Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes to show that newly developing expectations of the responsibilities of an editor-compiler, coupled with the continued elevation of physicians, have created an erroneous but lasting impression that Gerard was less an authoritative herbalist than a scheming plagiarizer.