INTRODUCTION

With the independence of Brazil in 1821, Portugal lost its most important source of overseas revenue. This led to a “colonial crisis”, which fuelled an intense debate about the future of the empire. The debate made clear that the prospects for overseas economic revival lay in Africa and led to the establishment of institutions such as the Portuguese Geographical Society, the Portuguese National Commission for the Exploration and Civilization of Africa, in 1875, and the organization of a series of scientific expeditions to the continent.Footnote 1

These expeditions, together with Portugal’s historical presence in Africa, laid the foundations for the territorial claims made at the Berlin Conference (1884–1885), covering the heartlands of Central Africa between Angola and Mozambique. Portuguese claims were repudiated by Britain and Germany because of their major interests in the region. In the General Act of the Conference, the principle of effective occupation prevailed. Colonial powers could obtain rights only over those territories that they effectively occupied, either by way of agreements with local leaders or by establishing an administrative and military apparatus to govern and guarantee the rule of law. Effective occupation also became the criterion to solve colonial border disputes.Footnote 2

Together, these political and economic changes forced Portugal to take action. To promote occupation, the state put in place a series of measures that fostered settlement, expansion of administrative and military structures, as well as economic development, either through its own initiative or by sponsoring private entities. These changes in Portuguese colonial policies led to important transformations in the politics, economies, and world of labour in Lusophone Africa, including Mozambique, marking the beginning of a new imperial economic cycle – which William Clarence-Smith has termed the “Third Portuguese Empire” – based on the extraction of raw materials and production of export crops through coercive and semi-coercive systems of labour exploitation.Footnote 3

This study examines the main changes in the policies of the Portuguese state in relation to Mozambique and its labour force during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stemming from political changes within the Portuguese Empire, the European political scene, and the Southern African context, and their impact on forms of labour and labour relations, by applying the taxonomy of labour relations and associated methodological approach developed by the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500–2000 to this specific case study. To meet the challenges involved, while at the same time facing a difficult economic and financial situation at home, the Portuguese colonial state made use of the most abundant and valuable resource available – labour, and put in practice an old tool used in empire building and management – outsourcing. By becoming a main employer in the territory, but also by granting private companies and neighbouring colonial states power to mobilize and allocate labour, the Portuguese state brought about important changes in labour relations in Mozambique. Slave and tributary labour was replaced by new forms of indentured and contract labour (serviçais/contratados) and forced labour (compelidos), while commodified labour in the form of wage labour (voluntários), the self-employment of peasant and settler farmers, and migrant labour to neighbouring colonies increased.

Our study discusses the impact of political change as an explanatory factor in shifting labour relations in Mozambique. The analysis is based on a dataset built using demographic and statistical information gathered from several Portuguese archives and libraries, including population counts, census data, reports from state and concessionary companies’ officials, and secondary literature, in particular the seminal studies by Frederick Cooper and the award-winning book Slavery by Any Other Name by Eric Allina, which gave voice to the labour experiences of Africans and their agency in labour struggles against colonial exploitation in Mozambique.Footnote 4 The classification of labour relations is based on the taxonomy developed by the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, and the analysis focuses on the comparative study of two chronological cross sections: 1800 and 1900.Footnote 5

PORTUGUESE RULE, ECONOMY, AND LABOUR RELATIONS, C.1800

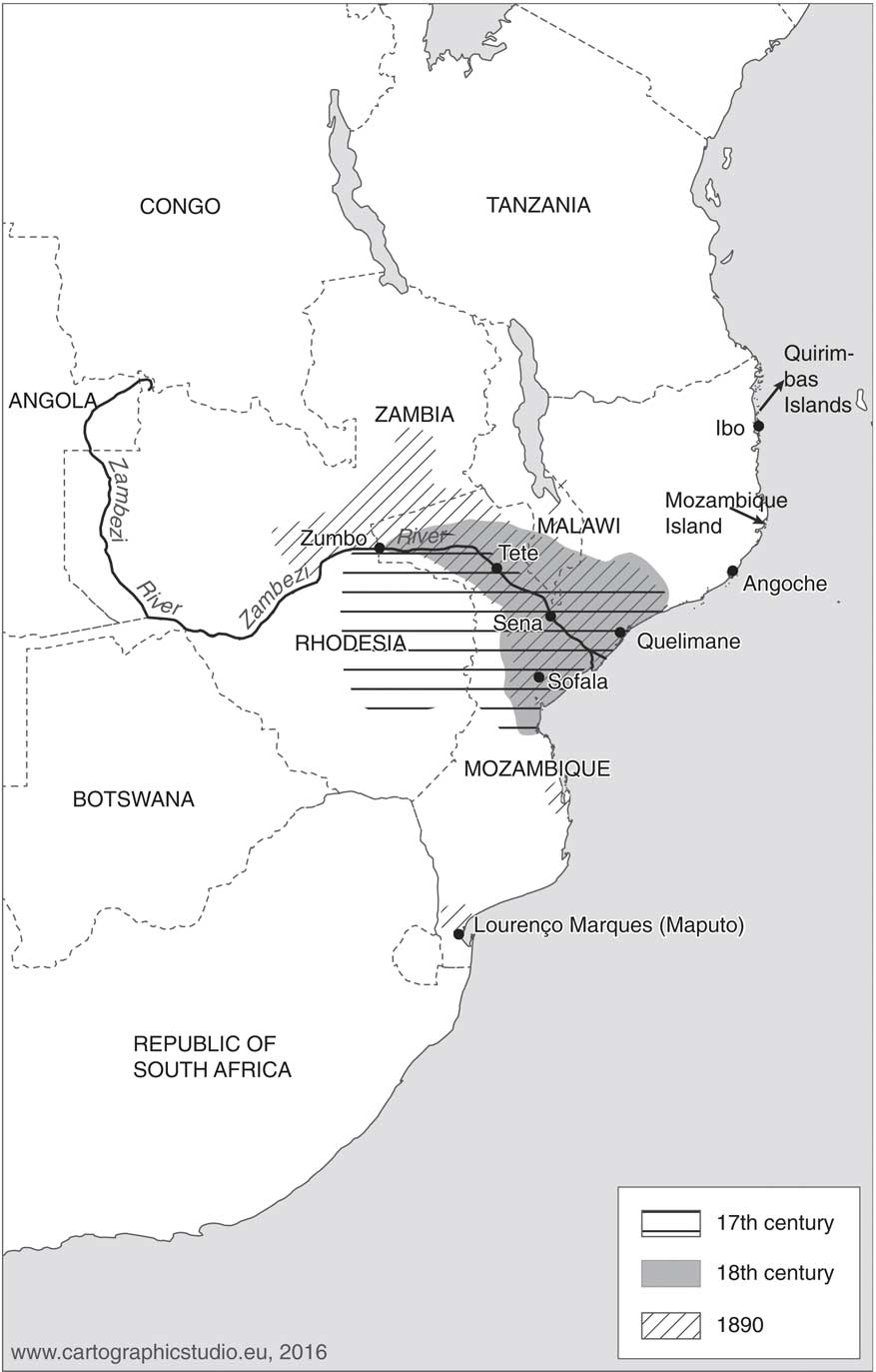

By the early nineteenth century, Portuguese influence in East Africa was still limited to a strip of land along the Zambezi Valley, starting on the coast between Sofala and Quelimane and stretching towards the heartlands, reaching as far as Sena, Tete, and Zumbo.Footnote 6 In the course of the century, Portugal also came to control several coastal areas, including the Quirimbas islands, Ibo, Angoche, Inhambane, and present-day Maputo. During this period, Portuguese influence also reached south-east Zambia and southern Malawi (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Portuguese influence in East Africa, 1500s–1970s. Source: Malyn Newitt, Portuguese Settlement on the Zambesi: Exploration, Land Tenure and Colonial Rule in East Africa (New York, 1973), p. 15.

Free Africans (colonos) constituted the majority of the economically active population (c.eighty-seven to ninety per cent) both in and outside the areas controlled by and under the influence of the Portuguese state and Prazos da Coroa, located along the Zambezi Valley and held by families of Portuguese descent. The Prazos da Coroa was a system of land tenure, regulated by the same principles as the Roman law contracts of emphyteusis, and put in place by the Portuguese Crown from the seventeenth century onwards to attract settlers to the region of the Zambezi Valley.Footnote 7 From an economic viewpoint, they were similar to medieval manors in how they were run and the types of relationship established between land tenants and peasants. However, as Allen Isaacman and Malyn Newitt explain, “from the African point of view they were essentially chieftaincies and as such part of a complex system of social and economic relations bounding together all the people in the region”.Footnote 8 The Prazo system was a form of outsourcing used by the Portuguese state also to promote the development of activities such as mining, agriculture, and trade, without having to invest much in human and financial resources. The management of trade routes between Mozambique and Goa (the headquarters of the Portuguese Estado da Índia) had also been under private management. This was a common and old practice used by the Portuguese state also in the Atlantic, where settlement and economic development were initially carried out by private entrepreneurs and consortia.Footnote 9

Alongside work in the Prazos, Free Africans were also engaged in five main activities: gold extraction in surface-mining workings located in the Central African heartlands; elephant hunting (as a source of meat and ivory); foraging for honey, wax, and wood; subsistence agriculture, including the production of maize, millet, wheat, sugar, tobacco, and groundnuts (and oil); as well as the transport of agricultural surplus, ivory, gold, foraged goods, and enslaved Africans to important inland-Footnote 10 and coastal-trading centres, such as Tete, the Island of Mozambique, Inhambane, and Quelimane.Footnote 11 The slave trade was controlled mainly by the Makua people, whereas elephant hunting was dominated by Maravi, Lunda, and Bisa peoples. Caravan trade between the interior and the coast, on the other hand, was dominated by the Yao people.Footnote 12 In all communities, agriculture was mainly the women’s concern, with male seasonal participation only to help clear the fields and during harvesting.Footnote 13 Part of the gold, ivory, honey, wax, and agricultural production ended up in the hands of local authorities, either of African or Portuguese descent, in the form of tribute payment.Footnote 14 Tribute in the form of labour was often also demanded by African village and community chiefs as well as by the Prazo tenants of Portuguese descent, in exchange for the protection they offered.

The work and products paid as tribute to the Prazo tenants were not only for domestic consumption, but also to supply small urban centres, provision ships, and for export through the coastal ports. The products obtained through farming, hunting, fishing, and foraging also fed villages and families of Free Africans. Free Africans were, therefore, involved in various labour relations. In their capacity as village leaders and heads of families, their involvement in the production of goods to guarantee the livelihoods of their family and community members should be seen as work for the household, as leading kin producers, and community redistributive workers (LabRel 4a+7, see Table 1). The remaining members of these villages and families, including women and other dependants able to work, were often involved in the production of goods for domestic consumption within the family and village as dependent family members, i.e. kin producers (LabRel 4b, see Table 1, and Table 2 for combinations of labour relations). In addition, the labour relations established between the colonos and Prazo tenants fall into another type of employment, i.e. tributary work and commodified labour for the market (LabRel 10+16, see Table 1). In this category the tribute assumed two forms: work and products. Thus, the colono had simultaneously a relationship of dependence towards the Prazo tenant, being obliged to work his land, as well as being obliged to pay a tribute in kind to the aforementioned Prazo tenant, which was mainly directed to supply the market economy. It is likely that identical labour relations existed between Free Africans and African local chiefs.

Table 1 Labour relations in Mozambique, c.1800 (guestimates).

Table 2 Combinations of labour relations in Mozambique, c.1800 (guestimates).

Sources: Based on late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century population charts, and inventories of the Prazos of the Mozambican territory controlled by the Portuguese, including information on professions, available in the Portuguese Overseas Historical Archive (AHU).

Observations: Calculations made by the author, based on the taxonomy of labour relations. For further details, see Filipa Ribeiro da Silva, “Relações Laborais em Moçambique, 1800”, Diálogos, 17 (2013), pp. 835–868, 860–861.

Enslaved Africans formed the second largest group among the economically active population – about nine to twelve per cent. This group comprised three main categories: rural and urban slaves, and slaves for export. Rural slaves formed the largest group. Most of them lived and worked in the Zambezi Prazos or nearby villages under the jurisdiction of Prazo tenants. Many of these slaves had been attached to the land and its tenant through a “system of reciprocal obligations”. In this sense, the relationship between master and slave approached more that of feudal patronage and dependence than the forms of slavery that emerged in the Americas. In most cases, these slaves had their families and lived in their own villages, which fell under the jurisdiction of the Prazos and the local chiefs in territories outside the Portuguese sphere of influence. They often performed several tasks for Prazo tenants and local chiefs, while carrying out other activities, such as hunting, fishing, and foraging to guarantee their own subsistence. Over time, these slaves became known as Chicunda and were employed by their masters in the collection of taxes from the colonos, as well as on diplomatic missions, in the defence of the Prazo and dependent areas, and in trade, on behalf of Prazo tenants. The Chicunda, or Achicunda, in fact, comprised most slaves at the time. The remaining slaves also lived dependent on or in the Prazo itself and had a wide variety of roles. For example, the “Jesuit prazos employed cooks, bakers, barbers, tailors, washerwomen, masons, fishermen, seamstresses, carpenters, tillers, ironsmiths, boat-builders and gold miners as well as household and garden slaves”.Footnote 15 There were, however, some distinctions in the type of activities performed by male and female slaves. Most female slaves were occupied in agriculture and mining.

Urban slaves and slaves for export, on the other hand, were a constant presence in the Portuguese cities and fortresses along the coast, as well as in the Portuguese fleets sailing in the Indian Ocean and Carreira da Índia (i.e. the Portuguese Indiamen). They were either in transit as “slaves for sale”, or as workers – often as “slaves for hire”. In the latter case, they performed a variety of tasks associated with daily life in these spaces, including domestic service, street sale of products, and craftwork (LabRel 17, see Table 1, and Table 2 for combinations of labour relations).

Like the colonos, African slaves were involved in various labour relations. As village chiefs and heads of families (in the case of the Chicunda), they were engaged in the production of items at the village and family level to guarantee their survival and the livelihoods of their families and communities. In this capacity, they were household leading producers (LabRel 4a, see Table 1). The remaining slaves in these villages and families, including women, and other dependants able to work also contributed to the production of goods for domestic consumption, and should be seen as household kin producers (4b, see Table 1). The labour relations established between the slaves and the Prazo tenants were of another type, the so-called tributary work (LabRel 11, see Table 1, and Table 2 for combinations of labour relations). However, a significant part of the activities developed by slaves in rural areas was directed towards the production of foodstuff for local consumption, and goods for the market economy (LabRel 17, see Table 1, and Table 2 for combinations of labour relations). Revenue from the foodstuffs and goods produced for their master were kept by the latter.

In contrast, the population of Portuguese, mulatto, and Indian origin represented a small fraction of the economically active population – just 0.4 to one per cent. Many of these individuals combined different activities, including the leasing and management of Prazos in the Zambezi Valley, and military and/or administrative service to the Portuguese Crown, alongside trade in various products and enslaved Africans. On the one hand, as Prazo tenants they were employers of free Africans (colonos) and of enslaved Africans. They were, therefore, engaged in various types of working rela-tionships (LabRel 12a+13+14+18, see Table 1). On the other hand, many of these individuals, both men and women (particularly widows), were usually heads of households, which at the time functioned as production units, for both domestic and market consumption. They were, therefore, household leading producers (LabRel 4a+13, see Table 1) and their spouses and descendants were household kin producers. In the territory that fell outside Portuguese control, labour relations were likely similar to those outlined above, as Prazo tenants often adopted the practices of local African leaders to extract labour and wealth from the population living under their jurisdiction.

Evidence suggests that by 1800 labour relations in Mozambique were dominated by reciprocal labour, often in combination with tributary and commodified labour. Subsistence agriculture appeared to be combined with the sale of surplus to the market. Harvest activities were carried out in combination with other tasks, such as hunting, working as porters, etc. Work for subsistence of the household (reciprocal labour) was combined with production of surplus for the market (work for the market), as well as with tributary labour for heads of villages, chiefs, and Portuguese Prazo tenants. In terms of the gender division of labour, men hunted and cleared fields for harvest, worked as porters, and as an armed defence guard; women took care of household chores, agricultural production, the sale of surplus in the market, and mining. Children also participated in the economy of the household and the rural community by helping in light household chores and in agricultural activities.

There is no evidence of a real free wage labour market. In the main port towns engaged in coastal, regional, and intercontinental trade, Portuguese, Swahili, and Banyan merchants resorted to slave labour for domestic work, for offering all kinds of services (“slaves for hire”), for equipping the ships operating through these ports, and for work in the production of foodstuff in the surrounding fields to supply the towns. The number of people working exclusively for the market appears to have been rather small, especially the number of those working for wages paid in currency and who could freely dispose of their labour as a commodity.

This system of combinations of labour relations was broken with the advent of the modern colonial era in Mozambique and the development of a colonial economy that obeyed the capitalist logic of catering to international markets and maximizing profits, at the lowest possible financial cost and with the minimum of risk.

PORTUGUESE RULE, ECONOMY, AND LABOUR RELATIONS IN MOZAMBIQUE AFTER THE 1890S

With the triumph of the principle of “effective occupation” at the Berlin Conference (1884–1885) and given the interests of the British and German governments in Mozambique, land occupation and population control became urgent matters. To face these challenges, the Portuguese state resorted to outsourcing – outsourcing the responsibilities of occupation, but also the financial and human costs associated with such type of enterprise.

The outsourcing of sizeable sections of Mozambique in the late nineteenth century is often portrayed in the literature as something new. However, outsourcing had a long history within the Portuguese empire, even as regards labour recruitment. Since the mid-sixteenth century (at least) there had been a long tradition of outsourcing the supply of labour within overseas territories, in particular within the Atlantic World, where Portuguese, and later Brazilian, private merchants and state-sponsored chartered companies catered to the demands of planters and miners in the New World. In this context, the state outsourced the acquisition along the African coast, the transport across the Atlantic, and the sale in the Americas.Footnote 16 However, the “recruitment” of Africans in the continent itself, either by purchase or enslavement through kidnapping or war, was never controlled by the Europeans (neither by the Portuguese, nor by others), and was never really outsourced to private consortia or entrepreneurs.Footnote 17

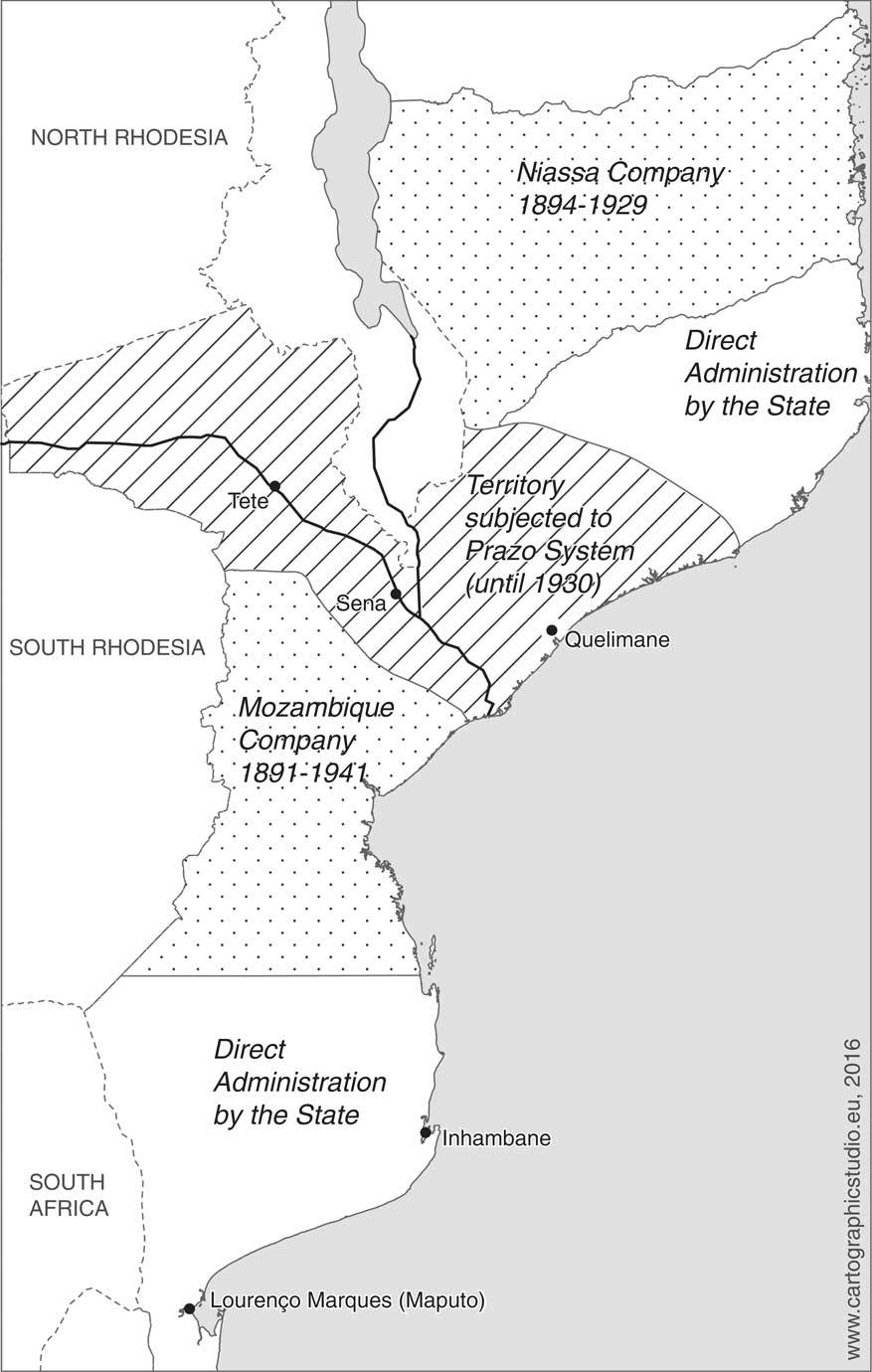

In Mozambique itself, there was a tradition of outsourcing dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as referred to before.Footnote 18 Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century, when faced with financial constraints, international political pressure, and economic rivalries, outsourcing the empire appeared to be the solution – an old solution. As in previous cases of colonial outsourcing, in Mozambique the state outsourced sections of territory where there was little or no Portuguese settlement, no defensive structures, no significant economic development, no bureaucratic apparatus, and no control over local African states/polities and their populations. So, the area of central Mozambique and the northern part of the territory were outsourced to two main companies chartered by the state: the Mozambique Company (1892–1942) and the Niassa Company (1891–1929) (see Figure 2).Footnote 19

Figure 2 Mozambique, c.1900. Areas administered by the state and concessionary companies. Source: Malyn Newitt, A History of Mozambique (Bloomington, IN, 1995), p. 366.

In contrast, the areas along the Zambezi Valley, where Portuguese presence dated from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including the districts of Tete and Quelimane, and the Island of Mozambique, were kept under the direct administration of the state. The same strategy was used in relation to the southern region of Mozambique – the so-called districts of Lourenço Marques (present-day Maputo), Gaza, and Inhambane, where settlement dated mainly from the nineteenth century in response to the growing interests of the British in the region – as control over these areas provided the British access to a port (Lourenço Marques), essential for the export of the raw materials and minerals being extracted in the Witwatersrand region and the Copperbelt, as well as to labour (migrants labourers) (see Figure 2).Footnote 20

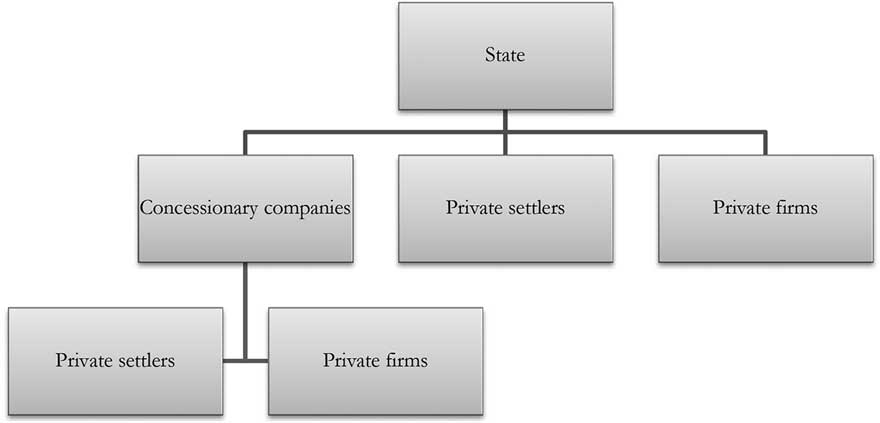

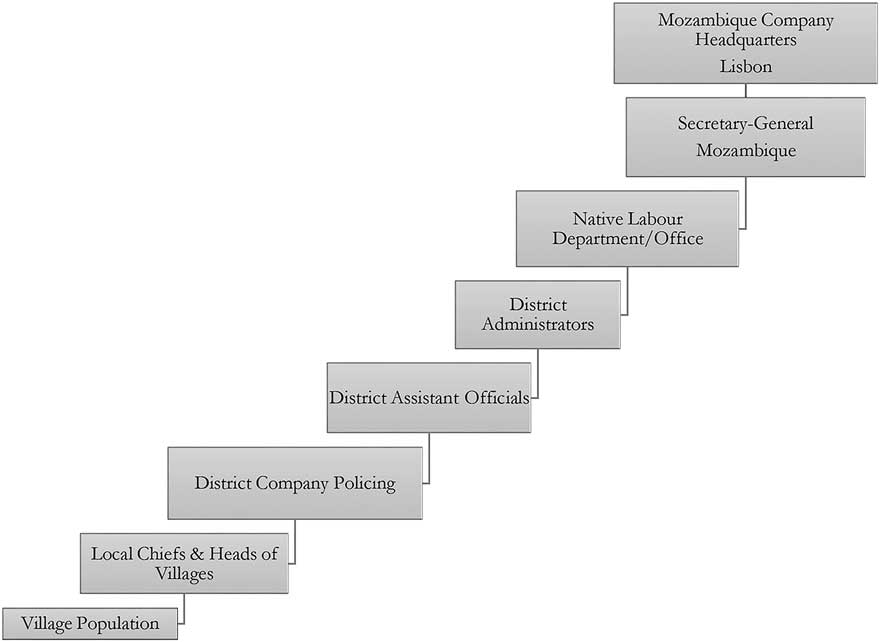

Although these sections of the territory remained under the direct administration of the Portuguese state, the state also granted concessions to private firms and entrepreneurs within its territories. Similar prerogatives were granted to the concessionary companies. We can, therefore, regard this whole outsourcing scheme as a chain (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Outsourcing management of land and labour, Mozambique, 1890s–1940s: A chain.

In keeping with the Portuguese tradition of colonial outsourcing, companies were made responsible for land occupation, settlement, the rule of law, economic development, construction of infrastructure, and the recruitment and management of labour within their territories. For this, they were granted permission to organize and retain an active police and military force, to establish an administrative apparatus, to issue their own legislation, to collect taxes, to take population censuses, as well as to act as recruiters, allocators, and employers, and as mediators in labour conflicts.Footnote 21

However, in late nineteenth-century Mozambique outsourcing was done on a larger scale and reached a whole new level. For the first time, vast areas of the African continent were being granted to companies authorized to issue their own regulations and have their own currency and police force.Footnote 22 Also, for the first time, private enterprises were explicitly allowed and encouraged to subjugate African leaders, enrol the African population, and in this way recruit, allocate, and control labour in the African continent itself. In fact, the establishment of the Mozambican concessionary companies brought the outsourcing of labour supply and transport that had dominated Portuguese participation in the transatlantic slave trade into the African continent. In the areas controlled by the companies, company officials engaged directly in the enrolment of people declared “fit to work”, the forceful “recruitment” of workers, and their allocation to various employers and different tasks. In those areas directly administered by the state, officials were involved in similar activities. However, to perform their roles as recruiters, allocators, employers, and mediators, companies and the state were to a great extent dependent on the voluntary or coerced cooperation of African chiefs of villages and of vaster territories, as previously with the supply of slaves for the early modern transatlantic slave trade and as is explained in greater detail in the following paragraphs. More importantly, for the first time concessionaries had at their disposal the means of the modern state: advanced military technology, a police force, modern statistics, etc. These allowed companies to exercise an unprecedented level of control over land and population in Africa – even though their control was limited geographically and the local population developed strategies to circumvent control by the state and the concessionary companies.

In order to become recruiters and allocators of labour, the Portuguese state and the concessionary companies needed a legal basis and a moral justification. For this, the Portuguese state issued a new labour code in 1899.Footnote 23 This new code determined that all men “fit to work” had the moral obligation to do so – contratados. Work was, in fact, the means through which Africans could “civilize themselves”. As a consequence, men “fit to work” found without work or not having a clear professional occupation were deemed outlaws and, therefore, forcefully compelled to work – compelidos.

The new labour code gave the state and the concessionary companies the power to determine who was not “fit to work”, and to put in place the necessary means to “recruit” either voluntarily or forcefully those “fit to work”. Under the labour code, all men and youngsters older than fourteen years were, in principle, “fit to work”. Children under fourteen, women, and the elderly were exempt from the obligation to work. The same applied, too, to those with any physical and mental illness that incapacitated them from performing any work. However, in practice, children, women, and the elderly were often obliged to work, especially when men and youngsters over fourteen deemed “fit to work” were scarce. In 1907, the new Portuguese labour code required each African to work for four months per year.

The Portuguese labour codes were to be applied in the territories under the direct administration of the state and served as a guideline for the specific labour regulations issued by concessionary companies in their territories. However, in the territory of the Mozambique Company the period of work referred to in the regulations often exceeded the number of months defined in the labour code. In 1911, the Company set the obligation to work at six months and in 1920 extended it to one year.Footnote 24

However, labour codes and regulations alone were not sufficient to compel Africans to work for wages, because they had at their disposal a variety of means to guarantee their survival and to amalgamate wealth without being dependent on selling their labour to the Portuguese. In order to force Africans to sell their labour for wages, the Portuguese state introduced the hut tax. Initially, it could be paid with labour, but over time payment in currency was made mandatory. So, the goals of the labour codes and regulations and the tax system introduced by the state and companies were threefold: obtain manpower, extract revenue, and force Africans to enter the emerging colonial wage labour market. The obligations towards the colonial state and its concessionary companies were, in fact, strongly bound together, as failure to pay the hut tax resulted in coercion to work.

To organize the hut tax collection and recruit workers, the state and the concessionary companies used their administrative apparatus, setting up what looked like a labour recruitment chain. In the case of the Mozambique Company, the headquarters in Lisbon delegated these responsibilities to the Native Labour Department (in existence between 1911–1925). These responsibilities were then transferred down the chain to the secretary general in the territory, and subsequently to the district administrators, their assistants, and police officers. The district administrators, either in person or through their assistants, were responsible for population censuses, tax collection, and workers’ recruitment. To do so, they relied on local chiefs and heads of villages. These were expected to collaborate with the officials of the Mozambique Company (as well as the officials of the state in the territories under direct administration) in selecting and providing men “fit to work”, collecting the hut tax, capturing workers who had left their assigned jobs before the end of their contract, and/or providing replacements for missing workers (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Labour recruitment chain – Mozambique Company, 1911–1925.

Chiefs often resisted these demands. The colonial state and its concessionary companies had, therefore, to resort to various strategies to gain their cooperation.Footnote 25 Violence, threats, hut tax exemption, gifts in cash and/or goods, payment of fixed amounts in cash, or payment of a fixed sum per worker supplied were among the most common practices used to entice and/or compel chiefs to cooperate.Footnote 26 It is, however, worth noticing that, despite agreeing to collaborate with the colonial authorities, chiefs tried to safeguard their own interests and the interests of their communities. This was often achieved through negotiations, which could include offers of free work in the region in exchange for exemption from the obligation to work four or more months in other regions.Footnote 27 This way chiefs could keep manpower within their territory and guarantee that men worked for the companies and colonial state when they were not needed for agricultural work and other tasks. Chiefs thereby tried to keep the local economy and labour force in balance. This allowed communities to produce enough for their subsistence, as well as some surplus to sell in the closest markets. Men still had time throughout the year to find short-term wage labour. The payment received for their work as well as the money made by selling any surplus were used to pay the hut tax.

After 1926, in reaction to the growing criticism of the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization (ILO) concerning forms of labour and labour conditions in the Portuguese-African colonies, the directors of the Mozambique Company abolished the Native Labour Department and authorized a privately run Native Labour Association to operate in the territory. However, its recruitment activities were not very successful, resulting in a labour crisis in the territory in subsequent years. This was made worse by several natural disasters, forcing the Company to reassume its role as labour recruiter.

The “labour crisis” was widespread because the Company used to recruit and redistribute workers to other employers. White settler farmers, firms in the financial, shipping, and agricultural sectors, like the Bank of Beira and the Buzi Company, involved in sugar production, were among the main beneficiaries.Footnote 28 The labourers recruited were often allocated to work on maize farms, in clearing operations in the bush to reclaim agricultural land, and in mines, as carriers (machileiros) (see Figure 5), on plantations, and in construction, etc. For private employers, this labour supply came at a price. Employers had to pay for each worker supplied and were expected to pay a wage, provide clothing, accommodation and food, and grant workers a two-hour break daily for rest and Sunday as a holiday.

Figure 5 Machileiros in Mozambique. This photograph shows a Norwegian colonist in Mozambique being carried by the traditional Machila, c.1900. The use of Machilas to transport Europeans and wealthy people was common practice in the Portuguese empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including in Angola and Brazil. Private collection of Elsa Reiersen. Used with permission.

In those areas directly administered by the state, the recruitment process is likely to have run along similar lines.Footnote 29 The state catered to its own labour needs, and also acted as indirect allocator of labour for private entities by authorizing concessionary companies, including the Mozambique Company, and foreign labour recruitment associations to operate in those areas under its control. In the southern districts (Lourenço Marques, Gaza, and Inhambane), under the agreements between South Africa and Portugal – the first dating from 1897 – a South African recruitment agency by the name of the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WENELA) was authorized to operate a recruitment station there. The Rhodesian Native Labour Bureau, established in 1903 to cater to the labour demands of the Rhodesian Copperbelt and its mining sector, was also authorized to recruit in the same areas.

How did all these changes affect workers, their forms of employment, their working conditions and their labour relations with their employers? By 1900, the state and concessionary companies had forced the development of a wage labour market, mainly for males, promoting the development of labour as a commodity for the capitalist-oriented market. Although labelled “contract” labour, the recruitment and employment systems were put in place using coercion, because, even though employees were paid, many workers were unwilling to sell their labour freely to the market. Working conditions were identical to what nowadays is defined as modern forms of slavery. Non-payment, delayed payment, deduction of workdays from salaries, insufficient clothing, food rations, and poor accommodation facilities were common complaints among workers against their private employers. The use of violence, threats, extension of contracts beyond the fixed duration, and refusal to grant daily hours for rest and Sundays as a day off were also usual. Some workers performed labour equivalent to indentured work for the market (immediately after the abolition of slavery indentured workers were often called serviçais, over time they also became known as contratados); others were in situations of effective forced labour for the market (compelidos). This represented an increase in unfree commodified labour for the market (see Table 3). In fact, only skilled workers retained some freedom of choice – the voluntários. They were able to voluntarily offer their work to the wage labour market and were often better paid and had better working conditions.

Table 3 Labour relations in Lourenço Marques and its outskirts, 1912.

Sources and observations: Calculations by the author based on data from the Census of the Population of Lourenço Marques – 1912 (present-day Maputo) and the Census of the Population living in the outskirts of Lourenço Marques – 1912, and on the taxonomy of labour relations developed by the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500–2000.

African men declared “fit to work” lost a lot of their freedom in relation to labour choices: when to work, whom to work for, how long to work, what work to do, and for how much they were willing to work, etc. This loss of freedom of choice changed their labour relations and had several consequences. On the one hand, they were forced to enter the wage labour market that was expanding under the sponsorship of the colonial authorities and concessionary companies. On the other, they were often assigned work for long periods of time and in places distant from their home villages and communities.

The emergence of these new labour regimes also brought about transformations in the economies of households and rural communities in the region. Men involved in labour for the benefit of the household and community – reciprocal labour – decreased in number, while women were increasingly engaged in reciprocal labour, as, in principle, colonial authorities did not seek their work for the development of the commercial agricultural, industrial, and mining sectors. So, women were to a great extent excluded from the wage market that was forcefully emerging in the region under the “sponsorship” of the state and its concessionaries. It seems likely, too, that the number of children and elderly working, especially in reciprocal labour, increased to replace those men who were recruited to work elsewhere.

However, the development of colonial capitalism in Southern Africa and the subsequent expansion of the mining and commercial agricultural sectors also offered business opportunities to African farmers. The construction of compounds to house labourers near mining fields and plantations created new consumption markets for foodstuffs traditionally produced by local farmers, such as maize and brewed beer. These products, often produced by women and which had in the past been a by-product of subsistence agriculture, would now be commercialized in Mozambique and exported to Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, in particular to the Copperbelt. Thus, apparently, the rise of the colonial state and colonial capitalism also stimulated the formation/expansion of a group of prosperous African independent farmers and cattle breeders, with profits from catering to the new consumption needs of male wage workers in the mining, agricultural, and industrial areas. Catering to the needs of the growing white colonial elites was also a profitable business. Others acquired the status of independent farmers with the help of remittances sent by their relatives who were migrant workers in Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, with these remittances being invested in the acquisition of livestock, land, seeds, and in the payment of hut taxes.

Although we lack comprehensive census data and information on the occupational structure of the entire Mozambican population for 1900, the data available for the city of Lourenço Marques and its outskirts, dating from 1912, illustrate the aforementioned changes in labour relations in the territories under the direct administration of the Portuguese state (see Table 3). Similar patterns are likely to be found in the territory of the Mozambique Company.

CONCLUSION

The evidence analysed here suggests that on the eve of the twentieth century the Portuguese colonial state became the main employer and redistributor of labour, both in relation to its own subjects and to subjects of other countries. On the one hand, the state developed into an important recruiter and allocator of labour within two specific regions of the territory of Mozambique, while simultaneously authorizing private entrepreneurs and firms to operate also as recruiters and employers within these same regions. These prerogatives were granted not only to its own subjects, but also to subjects of other states and their colonies, in particular South Africa and Southern Rhodesia. By using an old solution to promote settlement, development, and empire management – outsourcing – the state transferred state-like powers, though for the first time including recruitment and redistribution of labour, to two main concessionary companies, which carried out operations in central and northern Mozambique.

Together, the state and the concessionary companies brought the outsourcing of labour recruitment to the African continent and introduced to Mozambique important changes in the world of labour, including the development of a wage labour market, mainly for men, often working either in conditions identical to indentured work or forced labour, and the expansion of labour migration to neighbouring regions. The removal of men from the households and rural communities affected subsistence and local economies, leading to an increasing number of women, children, and the elderly engaged in reciprocal labour. However, the expansion of the colonial economy also contributed to the formation of a group of independent African farmers producing for the market and of skilled African workers also able to more freely offer their labour in the market – contributing to an increase in commodified labour.