Professors in American universities tend to be more politically liberal than the population overall, raising concerns about indoctrination among generations of conservatives (Bloom Reference Bloom1987; Buckley Reference Buckley1951; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2010; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2010) and mainstream media (Friedersdorf Reference Friedersdorf2012; Shields and Dunn Reference Shields and Dunn2016; Wooldridge Reference Wooldridge2005). Research suggests that these concerns have been overstated because university faculty have been found to be more politically diverse and less radical than some portrayals suggest (Gross and Simmons Reference Gross and Simmons2014); faculty ideology has little, if any, effect on student ideology (Mariani and Hewitt Reference Mariani and Hewitt2008; Woessner and Kelly-Woessner Reference Woessner and Kelly-Woessner2009). Still, less is known about whether the expression of professors’ political ideologies is welcome among students who, nationally speaking, tend to self-identify most often as moderates, then as liberals, and least often as conservatives (Eagan et al. Reference Eagan, Stolzenberg, Zimmerman, Aragon, Whang Sayson and Rios-Aguilar2017). Do students avoid partisan professors?

BACKGROUND

There is an enduring fascination with the politics of both students and professors on American campuses. A recent national survey of college students found that liberalism is growing in popularity and more students feel eager to protest on typically liberal policy issues, including affirmative action, legalization of marijuana, and abortion rights (Eagan et al. Reference Eagan, Stolzenberg, Zimmerman, Aragon, Whang Sayson and Rios-Aguilar2017). Assessments of faculty ideologies occur regularly, revealing that professors tend to be liberals, especially in the social sciences (Gross Reference Gross2013; Gross and Simmons Reference Gross and Simmons2014).

The generalization that college campuses are venues for liberal professors to indoctrinate liberal students has spawned numerous empirical studies about students’ perceptions of their professors’ politics. O’Brien and Pizmony-Levy (Reference O’Brien and Pizmony-Levy2016) found that students are more impressed by professors whose research engages with activism, even when that activism suggests liberal leanings. A study by Woessner and Kelly-Woessner (Reference Woessner and Kelly-Woessner2009) suggested that although professors are rarely able to conceal their politics from students, an observed shift to the left by students was unrelated to their professors’ ideologies. In other studies, Kelly-Woessner and Woessner (Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2008; Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006) found that students learn more from and give higher evaluations to professors whose ideologies match their own, putting conservative professors at a disadvantage.

However, less is known about how professors’ politics make their classes more or less attractive to students. Research on which professor characteristics students prefer has shown cognitive traits to be important. Among them, communication, organization, and teaching skills are most preferred by students (Miron and Segal Reference Miron and Segal1978; Slate, LaPrairie, and Onwuegbuzie Reference Slate, LaPrairie and Onwuegbuzie2009; Young and Shaw Reference Young and Shaw1999). Students also like professors who are challenging and knowledgeable, connect content to students’ lives, and respect their ideas (Acker Reference Acker2003). Thus, professors with histories of political activism could be attractive to a student of political science because they likely would bring a passion for the content and share experiences that make the content more real. In turn, generating student interest makes achieving educational success more likely (Tinto Reference Tinto2017). At the same time, fairness also is a valued trait (Slate, LaPrairie, and Onwuegbuzie Reference Slate, LaPrairie and Onwuegbuzie2009), and students may fear that politically active professors will not treat fairly students with opposing views.

The salience of the current political climate (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018) as well as the treatment of students as customers (Barr and Turner Reference Barr and Turner2013) give importance to the issue, as do the competing interests within higher education (Rothman, Kelly-Woessner, and Woessner Reference Rothman, Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2010). This study asks whether a course becomes less attractive to students when the instructor is a known partisan. It also explores how students’ political outlook affects their interest in these professors. These questions are important for faculty in making decisions about maintaining political neutrality in their teaching, for institutions concerned about the political climate on campus, and for those concerned about academic freedom (Gormley-Heenan Reference Gormley-Heenan, Gormley-Heenan and Lightfoot2012).

This study asks whether a course becomes less attractive to students when the instructor is a known partisan.

HYPOTHESES

Three hypotheses were tested. First, students may be wary of partisan professors. This neutrality hypothesis (H1) assumes, as Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2010) argued, that students would find it undesirable for ideological teachers to bring politics into the classroom. A second hypothesis states that students may welcome an ideological professor when their ideologies agree (Kelly-Woessner and Woessner Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006, Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2008). Under this political tribalism hypothesis (H2), students prefer professors who share their ideologies and avoid those with opposing views. A third hypothesis argues that because liberal professors are so common, a conservative professor would be a welcome change. With a nod to an editorial from Georgetown University’s student newspaper calling for the hiring of more conservative professors, this “Hoya” hypothesis (H3) suggests that students who are liberal, moderate, or conservative would welcome a chance to learn more from a conservative point of view.

METHODS

I tested these hypotheses with an experiment in which college students were asked to read a description of a fictitious political science course followed by a randomly assigned description of the instructor and then answer questions about their interest in the course, their interest in another course with the instructor, and their perception of the instructor’s expertise. For a touch of realism, the instructor’s name was redacted and only the title “Dr.” was presented, as though the course and instructor were present at the institution, which they are not. Figure 1 shows the prompt and questions as presented to the experiment participants.

Figure 1 Prompt and Questions Presented to Experiment Participants

Survey software randomly assigned each participant the liberal Democratic instructor, the conservative Republican instructor, or an instructor without any indication of ideology.

To isolate the appeal of the professor from that of the course topic, analysis focused initially on the second question, “How interested would you be in taking a different class with this instructor?” Responses could be influenced by being a political science major, having interest in politics or current events (measured by the number of times per week they consumed news other than sports), leaning left or right (on a scale of 1 to 7, extremely liberal to extremely conservative),Footnote 1 or gender. Therefore, I controlled for those variables in ordered logit regression models, with reported degree of interest (1 through 5) in taking an unspecified course with the professor as the dependent variable. I tested the first hypothesis with a dummy variable indicating that the professor’s description identified a party and an ideology. I tested the second hypothesis by using a dummy variable indicating a match between the student and the professor’s political affiliation, as well as a political-party mismatch dummy variable. I tested the third hypothesis by testing what association participants’ interest had with a professor described as Republican and conservative. Further analyses divided the sample by political affiliation, always using interest in an unspecified course with the professor as the dependent variable, except for the final model in which interest in the described course is the dependent variable.

SAMPLE

The experimental instrument appeared within an omnibus experiment conducted by the Political Science and Public Administration department at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte in the spring of 2018. The site of the study is a large public research institution with an acceptance rate of more than 60% and an enrollment of more than 28,000 students. On niche.com’s list of Most Liberal Colleges in America, the university ranked 657 of 687, between University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and State University of New York, Brockport. It earned a “green light” from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, an organization that gives this designation to schools that it views as providing strong free-speech protections. In other words, the school is not a hotbed of political activism that attracts radical students or professors and neither does its culture reflect any particular ideology. I further evaluated the context of the study by holding focus groups with campus chapters of College Republicans and College Democrats. In separate meetings, students from these groups described the university as “politically neutral,” with most students not interested in politics and rarely attending political events.

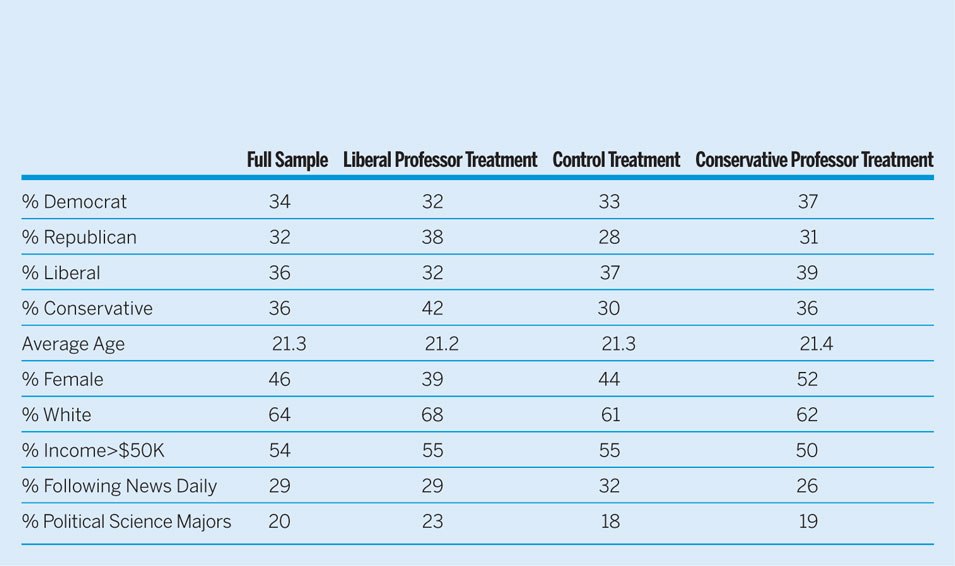

Subjects in this online experiment were recruited mostly from introductory political science classes that fulfill a general education requirement; they participated in the study via the online Qualtrics platform. Table 1 shows selected characteristics of the sample across the three randomly assigned treatments. The study included several questions that tested participants’ attention; those who did not answer questions correctly (12%) were eliminated from the analysis. Of note are the distributions of self-identified political attributes. Slightly more than one third of the sample self-described as Democrats, slightly less than one third as Republicans, and a smaller percentage as independents. Likewise, 36% identified as liberals, 35% as conservatives, and 21% as moderate (another 8% selected “other” or “not sure”). To establish that self-identified affiliations were accurate, I compared Democrats, independents, and Republicans in their responses to several ideology-oriented questions (the results are in appendix A).

Table 1 Characteristics of Experiment Participants in the Full Sample and by Treatment Group

RESULTS

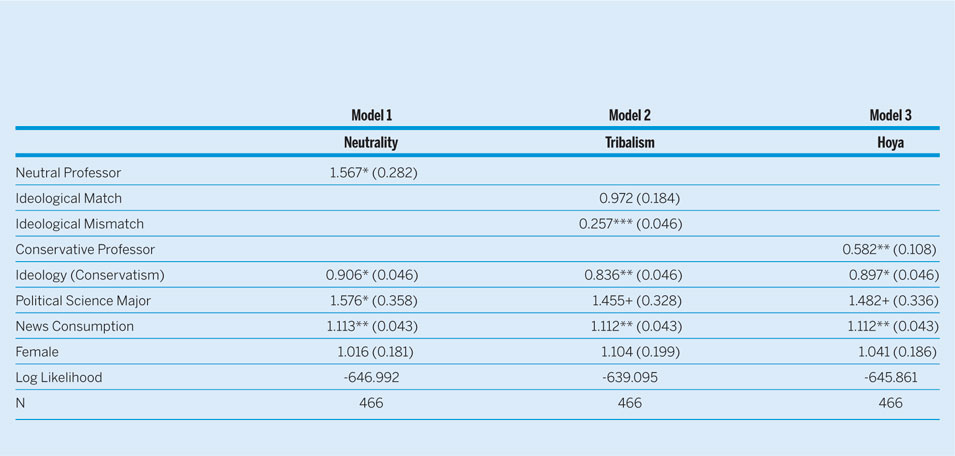

Compared to professor descriptions that were partisan, political neutrality was associated with an increase in participants’ interest (model 1 in table 2). Among partisan participants, an ideological match with a professor did not increase interest over the politically neutral control condition, but a mismatch significantly reduced interest. In the third model, a conservative professor made a course less appealing to participants. In all models, conservative students were less likely to express greater interest whereas political science majors and those that followed the news were more likely to do so. Participants’ gender had no significant associations.

Among partisan participants, an ideological match with a professor did not increase interest over the politically neutral control condition, but a mismatch significantly reduced interest.

Table 2 Odds Ratios for Expressing Greater Interest in Taking an Unspecified Course with the Professor as Described

Notes: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, + p<0.10. Standard errors in parentheses. Robustness checks are addressed in appendix C.

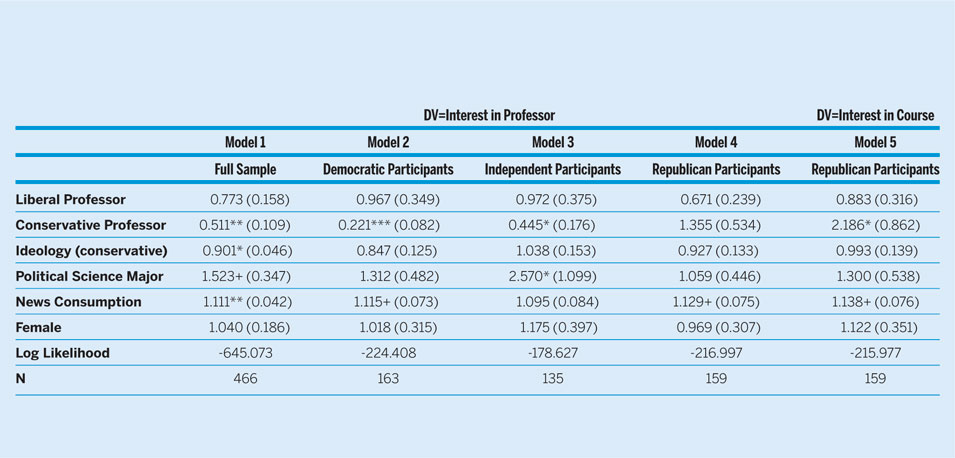

So far, the models only control for participant ideology but do not account for how participants’ responses to the main independent variable may differ by their ideology. In model 1 in table 3, which includes all participants, conservative professors’ classes were less appealing. When limiting the analysis to students identifying as Democrats, the dislike for conservative professors was strong: the likelihood of expressing greater interest decreases by more than 75%. Independent students showed a similar but weaker association. Odds ratios for Republicans are statistically insignificant in model 4; however, when the dependent variable is interest in the course on ideologies taught by the professor (rather than an unspecified course), the preference for the conservative professor became statistically significant (model 5). When the item asking for a judgment of the professor’s expertise was the independent variable (see appendix B, model 1), no statistically significant odds ratios resulted. This suggests that although expertise made the professor more appealing, political activism did not affect students’ perception of expertise (see appendix B, model 2).

Table 3 Odds Ratios for Expressing Greater Interest in Taking an Unspecified Course with the Professor Described, by Participants’ Political Ideologies

Notes: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, +p<0.10. The dependent variable for model 5 is interest in the political ideologies course. Standard errors are in parentheses. In models 1–4, the dependent variable is expressed interest in “a different course with this professor”; however, in model 5, the dependent variable is expressed interest in the course on contemporary political ideologies with the described professor.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Participants in this study preferred instructors who were politically neutral; however, their rebuff of overtly political professors was driven mostly by liberal and moderate students rejecting conservative professors. Although political tribalism is nothing new, viewing these results through the lens of political tolerance in the university could raise concerns. Abramowitz and Webster (Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018) identified negative partisanship as an explanation for recent voting patterns in America and found it especially strong among individuals who scored low on personality traits of agreeableness, extraversion, and emotional stability. Similarly, Gift and Gift (Reference Gift and Gift2015) found that job applicants in the minority political party received fewer callbacks, whereas applicants in the majority party received no benefit over neutral applicants. However, in the context of a politically neutral public university, the stronger avoidance of politically active conservative professors by liberal and moderate students warrants consideration.

Commentators such as Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2010) and Shapiro (Reference Shapiro2010) might argue that the results suggest that liberal students are intolerant and have come to expect universities to protect them from ideas that challenge their worldviews, whereas conservative students expect the opposite. This conclusion may go too far, however, because the behavior of independent (and moderate) students resembles more that of liberal students than conservative students (see table 3, model 3). If it were liberals’ intolerance of conservative ideology that drove the lack of enthusiasm for conservative professors, we would expect to see politically neutral students respond either positively to conservative professors (reflecting H3) or reject both liberal and conservative professors (reflecting H1 and H2). However, they do neither; unaffiliated students exhibit no change when shown a liberal professor and respond negatively to a conservative professor. For some reason, skepticism toward conservative professors is more common than the third hypothesis predicted. Succinctly, openly conservative professors are polarizing, even before they give their first lecture.

Succinctly, openly conservative professors are polarizing, even before they give their first lecture.

Beyond a distaste for conservatives, responses of liberal and moderate students may reflect an expectation that conservative professors will be less fair. It could be that a conservative instructor is such an anomaly that there is uncertainty about how class will be conducted. Additionally, during data collection, Republicans controlled the presidency, both chambers of Congress, and both chambers of the state legislature. Therefore, rejecting a conservative professor in this study might have been an opportunity for participants to resist the government in power or to symbolically demonstrate unity with the Left by exhibiting intolerance for the Right (Claassen and Gibson Reference Claassen and Gibson2018). The fact that conservative students were less likely to express interest in the professor supports the notion that they want to avoid classes in which ideology will be a topic of discussion, except when it is taught by a conservative.

The significance of these findings depends on one’s interests. Conservative professors contemplating being more vocal about their beliefs may earn a small, enthusiastic following but may miss class enrollment goals or the opportunity to reach liberal and moderate students. University departments contemplating affirmative action for overtly conservative professors also may note that student interest is unlikely to increase as a result. In extreme settings, professors hiding their political activity may be a necessary—however unfortunate—strategy. Finally, conservative activists might achieve their goals more easily by calling for balanced teaching rather than balanced faculties. Overall, political neutrality at least is not unpopular among students.

LIMITATIONS

In the assessments of its politically active students, the university that was the site for this study is politically neutral. Although the advantage of this location is that the immediate political environment was unlikely to affect interpretations of treatments, students’ reactions to political professors could differ in other places, especially where the political climate is more salient. Results are not generalizable.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651900194X

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Dr. Cherie Maestas, Dr. Matthew Cawvey, and the POLS Lab at UNC Charlotte for conducting the omnibus experiments that produced the data for this research.