Introduction

All too forgotten in the history of International Relations (IR) and political theory, Mary Shelley (1797–1851) ought to be foregrounded in the future, especially as these fields of political science grow to recognise their intersections with literature, existential philosophy, and women's intellectual work.Footnote 1 In this Special Issue on existentialism and IR, a number of scholars engage literature, both ‘liminal’ and canonical, as a source or ‘site’ of political thought.Footnote 2 This extends a trend in mainstream IR scholarship, which has widened to consider literature and its relation to political thought.Footnote 3 This literary trend in mainstream IR arguably began in the aftermath of the First World War, when the Belgian playwright Émile Cammaerts argued in a 1922 article titled ‘Literature and International Relations’ that ‘the artists and the writers who have been able, through their genius, to make their national temperament better known and better appreciated all over the world, are perhaps the first pioneers of a League of Nations.’Footnote 4

By folding Mary Shelley's futuristic war and pandemic novel The Last Man (1826) into the history of IR, this article contributes to a renewed literary movement at the forefront of contemporary IR. While this school of thought – which I label ‘Literary IR’ – is just coming to be recognised as a distinct hermeneutical approach in political science and political theory, it has deep yet unsung historical roots, as this study of Shelley's novel The Last Man and its IR sources and existential legacies demonstrates. This insight into the long-range evolution of Literary IR – from Thucydides to COVID-19 – is one of the realisations that follows from examining the philosophical relationship between IR and existentialism in the political thought and plague literature of Mary Shelley.

Mary Shelley, Literary IR, and political science fiction

For her part in this process of developing Literary IR, Shelley creatively mined the ideas of international political thought as well as the themes of plague literature, the epic, the romance, and the gothic novel to help develop three new subgenres of modern science fiction (SF): post-apocalyptic, existential, and dystopian literature. From this mélange of literary forms arose her two SF masterpieces – Frankenstein (1818) and The Last Man (1826). These works prove to be more ‘political science fictions’ than ‘hard science fictions’, for they are broadly concerned with tracing the often-harmful impact of human artifice on the whole world across families, societies, species, and nations.Footnote 5 Unlike later ‘hard science fiction’ by Isaac Asimov and others that uses consistent scientific or mathematical reasoning to predict the consequences of making mechanised weapons, robots, spaceships, imperial galactic societies, and other forms of human artifice, Shelley's political SF is neither solely nor primarily concerned with rigorously extrapolating the future of technology and human society from present-day engineering inventions and scientific theories.Footnote 6

Frankenstein and The Last Man are rather concerned with delineating the tragic emotions and unjust social consequences associated with the repeated human failure to make peace, share love, and care for others and the world at large. The gothic and domestic horror of Frankenstein arises from the destructive passion of a chemist who uses science and technology to create a ‘human being’ without caring for it.Footnote 7 The existential and global terror of The Last Man derives from its slow and devastating exploration of the personal and political betrayals that exacerbate war, corruption, and a plague that appears to leave one lone human survivor, who lives to write the ‘history’ of the near extinction of his species.Footnote 8

Interpersonal and international conflicts, much more than science and technology, serve as plot devices for advancing the existential and post-apocalyptic themes of Shelley's classics of ‘poliscifi’.Footnote 9 By existential, I mean the contemplation of the meaning of life and death and their relation to the formation of personal and communal identities. By post-apocalyptic, I mean speculation on the aftermath of a devastating catastrophe that poses an existential (life-endangering) threat to a person, community, or species.

Shelley's poliscifi novels thematically represent the existential threat of death, abuse, war, and other catastrophes as surfacing in fraught familial and romantic relationships and spreading swiftly through and across cultures, states, and empires, like a ‘scourge’, ‘pest’, or ‘PLAGUE’.Footnote 10 The escalating parent-child conflict between Victor Frankenstein and his abandoned creature leads to the death of virtually everyone in his clan. The pestilential battlefields of a centuries-long war between Greece and Turkey spawn a lethal ‘epidemic’ that leaves Verney, the titular ‘LAST MAN’, alone amid the ruins of Rome to contemplate the future of humanity and the possibility of its extinction.Footnote 11 With her relentless focus on the deeper emotional conflicts that cause tragedy, injustice, and the annihilation of life itself, Shelley foregrounded the social and political problems associated with humanity's selfish, careless, and violent interventions in their wider environment.

Both Frankenstein and The Last Man are modern post-apocalyptic myths, in the sense that they use widely resonant allegories to envision the aftermath of human-made catastrophes.Footnote 12 Frankenstein's gigantic creature is a hulking metaphor for humanity's monstrous potential for self-and-other destruction. The war-driven epidemic of The Last Man is likewise a metaphor, writ even larger, for humanity's failure to contain its self-destructive behaviour even unto its own extinction. In Shelley's first novel, a man-made creature turns murderous in his quest for vengeance against his neglectful father-scientist. In her third published novel, a seasonal plague in Constantinople grows into a pandemic as domestic and international conflict circulates the airborne pathogen across borders and oceans through trade, travel, and war.Footnote 13

Although Frankenstein is far better known and studied, it was The Last Man that contributed to the philosophical traditions we now associate with post-apocalyptic, existential, and dystopian literature. By dystopian, I mean the opposite of utopian. Utopian literature depicts an ethical, social, or political ideal that is not yet realised. Utopia is Saint Thomas More's neologism, combining the Greek words ‘οὐ’ (not) and ‘τόπος’ (place), meaning ‘nowhere’.Footnote 14 Dystopian literature pictures the reverse image of utopia. As Margaret Atwood has argued from a liberal perspective, dystopias ‘warn’ readers of what to avoid if they want to preserve freedom, peace, rights, happiness, and justice from attempts at tyranny, conquest, and oppression.Footnote 15 The Last Man hybridises existential and post-apocalyptic themes in its dystopian vision of a late twenty-first-century Earth where even the world's leading republics of England and the ‘Northern States of America’ crumble under the pressure of a war-spurred pandemic.Footnote 16

Though most strongly associated with George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (1985), dystopian literature has roots in Shelley's poliscifi.Footnote 17 Orwell originally titled Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘The Last Man in Europe’, and represented its hero, Winston Smith, as ‘the last man’ in London to resist the contagion of totalitarian ideology disseminated by the all-seeing imperial regime of Big Brother.Footnote 18 A fan of gothic and SF literature since childhood, Orwell praised Mary Shelley in his 1944 review of English Diaries of the Nineteenth Century, and then, as we shall see, used strikingly similar language as this 1944 book's reprinting of her journal's May 1824 entry on ‘the last man’ in the torture scene of Nineteen Eighty-Four.Footnote 19

Atwood grew up reading Orwell and Shelley, and titled one of her first collections of poetry, ‘Speeches for Doctor Frankenstein’ (1966).Footnote 20 She set The Handmaid's Tale (and its 2019 sequel, The Testaments) in a post-apocalyptic North America of the early twenty-first century. An epidemic of infertility – caused by sexually-transmitted disease, the seeping of toxic waste into the environment, and the spread of political and sexual corruption in Western capitalist society – leads to a coup d'etat of the United States by a fundamentalist Christian terrorist organisation that seeks to restore female fertility by forcing a sector of women to serve as sexual slaves and surrogates for the military commanders and their wives.

Like any myth, ancient or modern, one recognises the story of The Last Man before even reading it. This is due to the symbolic resonance and vast cultural influence of its central figure: the ‘last known survivor’ of a massive existential threat like a postwar plague.Footnote 21 The cultural canonisation of Shelley's story has been accomplished largely through its adaptation into two important post-apocalyptic plague novels, M. P. Shiel's The Purple Cloud (1901) and Richard Matheson's I Am Legend (1954).Footnote 22 Shiel's novel is notable for introducing a recurring comic and romantic twist to the tragedy, wherein the seeming last man meets and falls in love with the apparent last woman.

Shelley's and Shiel's novels were also successfully translated for the screen and stage, beginning with a comic silent movie and Broadway musical The Last Man on Earth (1924) and extending to the Hollywood doomsday film The World, the Flesh, and the Devil (1959) starring Harry Belafonte.Footnote 23 But it was Matheson's novel about the ‘last man in the world’ to survive a vampire plague that has secured the ongoing reception of the last man trope in contemporary SF and horror literature, cinema, and television.Footnote 24 After its initial filmic adaptation as The Last Man on Earth (1964), starring Vincent Price, Matheson's version of the last man narrative begot The Night of the Living Dead (1968), 28 Days Later (2002), I Am Legend (2007), and countless post-nuclear, pandemic, and zombie apocalypse movies and television series after them.Footnote 25

The Last Man theme in post-apocalyptic, dystopian, and existential political thought

While the literary legacy of The Last Man has been woven into popular culture, the novel's significance for philosophy and political thought has only begun to be charted. In the era of COVID-19, The Last Man has been recovered as the first major modern post-apocalyptic pandemic novel.Footnote 26 Here I foreground it as a vital literary and philosophical source for existentialism and its intersections with international political thought and dystopian literature. Comparing The Last Man with its probable sources and influences – from Thucydides, Hobbes, Vattel, and Voltaire to Stoker, Wells, Orwell, Camus, and Atwood – reveals Shelley's ethical and political concerns with the overlapping problems of interpersonal and international conflict. The Last Man dramatises how interpersonal conflict, if left unchecked, will spiral into the wider social and political injustices of violence, war, and other human-made disasters such as species extinction, pandemics, and a range of metaphorical existential plagues upon humanity such as loneliness and despair.

Despite these dark themes, Mary Shelley's authorship of The Last Man led to the development of a hopeful, post-apocalyptic existential response to the interlocking problems of interpersonal and international conflict. This future-oriented tradition of international political thought has aimed to rise above a pair of fatalistic fallacies: first, the metaphysical or existential belief that there is nothing after (or post) apocalypse, since extreme catastrophes may seem to bring to those who suffer them a final stop or absolute end to a state of human affairs; and secondly, following from this bleak premise, the nihilistic view that there is nothing to be done in the face of total war and other human-made apocalyptic disasters. Apocalypse, from this pessimistic perspective, is death without end.

By contrast, the post-apocalyptic tradition after Shelley returns apocalypse to its original meaning in ancient Greek (ἀποκάλυψις): a ‘revelation’ or ‘uncovering’.Footnote 27 In this Shelleyan tradition of post-apocalyptic political thought, it suggests the unveiling of a new way of life after personal or collective disaster. Shelley's dark yet ultimately hopeful vision of the future has shaped the aesthetic behind modern existential, post-apocalyptic, and dystopian fiction and philosophy, from Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, to Orwell and Camus, to Octavia Butler and Emily St. John Mandel. She and her followers in feminist SF – especially Atwood, Butler, and Mandel – have created a vital imaginative space for thinking about how personal change in response to conflict and disaster can lead to global change towards diplomacy, justice, peace, and a new cosmopolitan world order.

Post-apocalyptic political thought in this feminist vein offers a more hopeful and futuristic alternative to the pessimistic, absurdist, and nihilistic elements of canonical (and men-dominant) existentialisms, typically associated with Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Sartre, and Camus. We need more feminist and literary approaches to addressing existential questions in poliscifi to save the concept of apocalypse from its reduction to mere annihilation and catastrophe. By adding the aporetic prefix ‘post-’ to ‘apocalypse’, we join Shelley, Atwood, Butler, and Mandel in making room in Literary IR for the theorisation – or imaginative revelation – of new political futures after man-made disasters. On this Shelleyan and feminist reading of the original Greek, apocalypse is never the end, but rather is always the beginning.

The Last Man: A novel in ideas of international political thought

The daughter of two political philosophers, the anarchist William Godwin and the women's rights and abolition advocate Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley was raised by her father to debate over the dinner table the epistemological and educational ideas of Locke, Rousseau, and her late mother, who had tragically died from sepsis after giving birth to her.Footnote 28 Immersed from the very onset of life in the ideas of the Western tradition and particularly the European Enlightenment, Shelley saturated the story of her pandemic novel with the themes of international and global political thought from Thucydides and the Bible to Hobbes, Voltaire, Vattel, and Burke.

As a roman à clef – or allegorical study of the author's life story – The Last Man is best understood as a novel ‘in ideas’ instead of a novel ‘of ideas’.Footnote 29 The plot of Shelley's global plague novel is driven by the political philosophies that she debated first with her father and later with her lover and husband the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. But the novel, like Frankenstein, is not a mere ideological vehicle for the transmission of other writers’ ideas.Footnote 30 It is rather that her dystopian novel questions and dissects these received ideas from the Western tradition to reveal a new, utopian, cosmopolitan understanding of what world politics could and should be in the future.

Soon after the sixteen-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin eloped to Europe in the summer of 1814 with the unhappily married poet Percy Shelley, she noted in her journal that he read Thucydides.Footnote 31 Perhaps his interest in the History of the Peloponnesian War arose from the couple's recent trek through war-torn France, where whole towns had been razed by the invading forces of Russia during the last year of the Napoleonic Wars.Footnote 32 Since Mary kept an annual notation of her and Percy's reading in her journals, it is possible that they discussed Thucydides together or that she read the Greek historian but forgot to record it on the day or at year's end. What is certain is that The Last Man alluded to Thucydides’ famous account of the Plague of Athens: Verney notes with worry the arrival of the ‘plague at Athens’ after it leaves the battlefields near Constantinople via trade, travel, and military routes.Footnote 33

In 430 bce, after the Athenian general Pericles ordered the masses to hide behind the city walls from the invading Spartans, he unwittingly sealed them up with the plague brought into the city-state through its busy trading and naval port. About 100,000 people – a quarter of the population – suffered reddening fever, stertorous breathing, and maddeningly painful deaths because of this military strategy.Footnote 34 Mary Shelley, it seems, derived a political lesson from Thucydides’ account of the Plague of Athens, which she dramatised in The Last Man: bad political ideas and poor leadership decisions based on them make for fatal public policies in times of war and other crisis. Like H. D. in Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), Verney watches with anxiety as the plague sweeps into England from southern France, due to the failure of leaders in either country to prepare to stop it through suspension of trade, travel, military campaigns, and other politically institutionalised modes of disease transmission.Footnote 35 Set in the 2090s, her futuristic pandemic ultimately levels France, England, and all the world's other nations, enacting the war-driven political tragedy of the plague of Athens on a global scale.

Foreshadowing the insights of Derrida and his deconstructive philosophy, Shelley used the idea of ‘plague’ more as a loose, figurative concept than as a fixed, literal disease.Footnote 36 Tellingly, the plague does not even appear until about halfway through the novel. When Verney recalls that it arose in the war between Greece and Turkey, he renders ‘PLAGUE’ in all capital letters.Footnote 37 As Verney leads readers to comprehend his extraordinary existential predicament as the ostensible last man on Earth, ‘PLAGUE’ functions more as a capacious symbol of varieties of human-made destruction than as an actual pathogen. By keeping it mysterious whether its mode of infection was airborne, ‘contagious’ by physical contact, or both, Shelley refrained from defining ‘PLAGUE’ as a specific disease.Footnote 38 This omission is significant, given that she had a series of tragic experiences with the scourge of infectious disease. Three children she bore or cared for had died of dysentery, malaria, and typhus, while she and Percy lived in Italy between 1818 and 1822.Footnote 39 Then tragedy struck again when Percy died at the age of 29 in a sailing accident off the coast of Tuscany.

Perhaps because of the immensity of these losses, Shelley conceptualised ‘PLAGUE’ as an existential abyss: a bottomless sign for catastrophes. The introduction of the word midway through the novel marks its transition from a romantic epic, set at the exotic locations of Windsor Castle and Constantinople, into a speculative dystopian fiction about the failure of the world's governments to contain a novel and lethal epidemic. This abrupt change in genre provokes in the mind of the reader a deconstructive philosophical process of unmaking, or breaking down, the prevailing meanings of a cascade of synonyms for disaster: war, conflict, contagion, corruption, hardship, disease, deprivation, and death. As the godlike author of the first novel to chronicle the global spread of a species-decimating pandemic, Shelley leads readers to see how the plague unmakes world leaders’ bad political ideas and policies, revealing their tragic flaws as people and governments. This unmaking of a severely defective (or dystopian) world order uncovers the need to find new (or utopian) ways of making connections and communities on Earth. Shelley's political science fiction paradoxically reveals how critical analysis of the concept of disaster points the way towards overcoming it.

A studious reader of the Bible, Shelley revised the sacred story of Noah's ark in the final scene of The Last Man, while giving the ancient Hebrew myth a distinctively modern existential and post-apocalyptic twist.Footnote 40 In her fictional version of life after a flood of pestilence, the last man Verney sets out to sea – with his dog and the works of Homer and Shakespeare as his only companions – in search of other survivors.Footnote 41 He surmises that people, perhaps a ‘saved pair of lovers’ like Adam and Eve, must be safe in some remote location on Earth.Footnote 42 Once he finds them, he thinks, there might be the start of a new Edenic society that preserves the best of human culture (compassion, companionship, literature) and discards the worst (the plagues of war and other man-made conflicts). The plague's unmaking of the global impact of war and imperialism leads, paradoxically, to Verney's remaking of the imaginative conditions for love, hope, renewal, and even the prospect of a cosmopolitan peace.

Beginning with their joint devotion to Wollstonecraft and Godwin's progressive political ideas, the Shelleys became experts on the history of Enlightenment political thought from Hobbes to Kant.Footnote 43 They bought a copy of the 1816 French translation of Johann Gottlieb Buhle's Histoire de la philosophie moderne while they lived in Geneva that same year.Footnote 44 Buhle provided a lengthy summary of the international political thought of the Swiss political theorist and diplomat Emer de Vattel and its relationship to the earlier work on the law of nations by Wolff, Hobbes, Pufendorf, and Grotius. His 1758 treatise Le Droit des Gens (The Law of Nations) was quickly translated into English.Footnote 45 It was well known on both sides of the Atlantic for its contributions to just war theory and the idea of a diplomatic peace achieved through the cross-cultural and international leadership of ‘ambassadors’.Footnote 46

Vattel gained fame for defending the right of small nations to exist independently from more powerful states and empires. While he advanced a diplomatic and pacific view of the realisation of international cooperation across sovereign nations, Vattel justified the intervention of more powerful states on behalf of less powerful ones vulnerable to conquest. When they read Le Droit des Gens during the 1775 Continental Congress, American revolutionaries led by Benjamin Franklin found a two-fold model for a modern international practice of independent statehood: first, political leaders must show respect for the equal sovereignty of nations; and secondly, they must develop diplomatic alliances against imperial conquest and for international cooperation.Footnote 47

Vattel's Le Droit des Gens, with its final five chapters devoted to the theory and practice of ambassadorship, is the most proximate source in international political thought for Shelley's depiction of Verney as an ‘ambassador’.Footnote 48 Born a shepherd boy in the north of the republic of England, Verney befriends the dethroned royal family near their country estate in the 2070s. Adrian, the former prince turned republican political leader, sends him to Vienna to train as a diplomat, as ‘private secretary to the Ambassador’.Footnote 49 After two years of diplomatic service abroad, Verney returns to the court circle at Windsor Castle, with ‘a reputation already founded’, to serve his lifelong friend Adrian in his political career guiding the fledgling republic of England from a monarchical past into a democratic future.Footnote 50

Also in Adrian's court is Evadne, a Greek princess and daughter of the Greek ambassador to England. In imagining an international diplomatic circle at Windsor Castle, Shelley likely took inspiration from her friendship with Alexandros Mavrokordatos, the Greek prince, diplomat, and leader of the 1821 Greek War of Independence from Ottoman rule. During the 1810s, Mavrokordatos lived in exile from his homeland in the court of his uncle, the prince of Wallachia, then was educated at Padua in the Austrian Empire before he befriended and resided with the Shelleys at Pisa in 1820–1, when he tutored Mary in ancient Greek.Footnote 51

Beyond the example of Mavrokordatos's diplomatic career, Vattel's philosophy of ambassadorship as the art of forging ‘friendship’ between nations likely shaped her characterisation of Verney as a peacemaker.Footnote 52 Verney's life as a diplomat and citizen of the world begins with his friendship with Adrian and extends to shaping ‘friendship’ in all domains of life: from the romantic relationships of their court circle, to the battlefields of Constantinople, to the English government's pandemic response in London, to aiding the remnant of plague survivors in France and Italy.Footnote 53

The Shelleys likely encountered Vattel through Buhle, even though they probably bought his six-volume history of modern philosophy in Switzerland to learn more about Kant. Buhl provided a lengthy summary of his late eighteenth-century German contemporary Kant's three Critiques, which elaborate his epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics.Footnote 54 Buhle did not summarise Kant's political writings, however, including his utopian theory of a cosmopolitan peace achieved through a world federation of free republics. According to Kant's theory of ‘perpetual peace’, these republics would be united not as a world state, but through mutual regard of their sovereign independence from one another.Footnote 55 In this and other political essays from the French revolutionary era, Kant argued that an essential feature of a free modern constitutional republic was to respect the ‘universal right of humanity’ or ‘cosmopolitan right’ of citizens, whether they were from one's own country or another nation.Footnote 56 In his 1795 essay on perpetual peace, Kant favourably placed Vattel among the ‘sorry comforters’ of modern theories of international law: for he was a harbinger of an optimistic (though perhaps impractical) cosmopolitan philosophy of ‘universal hospitality’ towards fellow citizens of sovereign republics and the world itself.Footnote 57

Because Mary did not record in her journals her or Percy's reading of Kant's political writings, it is more likely that the cosmopolitan and diplomatic themes of The Last Man are rooted in her exposure to Vattel and other French-Swiss cosmopolitan writers than Kant. Another Francophone writer with ties to Geneva and Switzerland who may have inspired the character of Verney is Voltaire. Mary noted in her journals that she read Voltaire's Memoires, his ‘romans’, and his ‘Essay on Nations’ between 1815 and 1816.Footnote 58 From the 1769 Memoires and her own extensive travels around Geneva, she would have known that Voltaire left the city-state for Ferney in 1759, just across the border in France, to protest the Swiss republic's ban on theatre. Voltaire's fame in Ferney, and his liberal support of the theatre, arts, and industry there, led the town to rename itself Ferney-Voltaire in 1791.Footnote 59

The close match between the unusual surname Verney and Ferney-Voltaire suggests that Shelley may have wanted to associate the Voltairean town's avant-garde culture with the character of the ‘LAST MAN’. Voltaire's riotously funny novel Candide (1759) – a satire of Rousseau's optimistic belief in providence even after the massive, human-exacerbated disaster of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake – may have inspired the dark humor of Verney, who says he will ‘sit amidst the ruins and smile’ despite the very real possibility of human extinction.Footnote 60 Voltaire's anti-imperial, anti-slavery, and anti-church writings share The Last Man's concern with the realisation of true personal and political independence in opposition to past forms of religious and secular oppression. When he bravely strikes out to sea in search of other survivors, with Shakespeare, Homer, and his dog in tow, Verney evokes Voltaire's quixotic quest for a cosmopolitan conception of citizenship and independence, unlimited by national or religious roots, yet supported by love of the arts and compassion for others.Footnote 61

In the biographical allegory of The Last Man, Adrian stands for Percy and Verney for Mary.Footnote 62 Following the political ideas of Percy's ‘Declaration of Rights’ (1812), ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ (1819), and ‘A Philosophical View of Reform’ (1819–20), Adrian is the radical visionary of peace made through non-violent protest of oppression, modern representative republican government, and enfranchisement of the poor.Footnote 63 Mary/Verney take this radical vision of peace and justice and go global and existential with it. Despite being the last (wo)man left alone after losing everyone s/he loves, s/he finds a way to make peace with the world in all its darkness, by summoning hope for the preservation of a new way of life on Earth, even if the human species faces almost certain extinction.

Like Vattel, Verney/Mary deduces that there are universal ‘offices of humanity’ that extend beyond particular duties to care for and preserve one's own family, culture, and nation.Footnote 64 Vattel went so far as to argue that ‘every nation is obliged to cultivate the friendship of other nations.’Footnote 65 He defined ‘real friendship’ – whether between individuals or nations – as a ‘happy state’ that ‘consists in mutual affection’.Footnote 66 Verney/Mary takes this argument about the duty to cultivate friendships one step further. Once they existentially identify as ‘THE LAST MAN’ while writing down their strange life history, they extend Vattel's cosmopolitan ethic of friendship to other species. As he prepares for his journey towards the coast of Africa to seek other survivors, Verney keeps a mutt as his sole living animal companion and gives up hunting in favour of eating dried corn from granaries.

After the apocalyptic flood of plague, Mary's avatar Verney is the modern existential Noah, setting sail towards an uncharted horizon of humanity with his dog and his books. What is left for him is the possibility of bridging a Voltairean cosmopolitan citizenship with a Vattelian friendship with the whole creation in an ‘international society’ yet to be built.Footnote 67 This post-apocalyptic hybridisation of Voltaire and Vattel would entail a cosmic solidarity with and compassion for the world itself – what it was, what it is, and what it will be. In a reflection on the meaning of life and death near the end of his ‘HISTORY OF THE LAST MAN’, Verney articulates this epiphany: human beings inevitably die, and may even become ‘extinct’, but ‘humanity’ understood as humaneness need not, and must not, be extinguished, if his life as a human is to ultimately have ethical meaning.Footnote 68 By reconceiving the meaning of humanity after apocalypse, Verney paves the way for understanding humaneness or genuine compassion as post-human: for it arrives after the Anthropocene, yet in time to save the world from human-made destruction.

Mary, like her father Godwin, was a devoted reader of Burke, who was influenced by Vattel's philosophy of international law. A Member of Parliament who prosecuted Warren Hastings for his crimes against the indigenous peoples of British India, Burke took seriously the Vattelian idea that the law of nations justified states’ intervention on behalf of oppressed peoples against their tyrants.Footnote 69 In The Last Man, Shelley has the diplomat Verney quote or adapt the words of Burke on several occasions, reaffirming the wisdom of his pacific and optimistic views on being a good leader through following others, and on the persistence of the best of human culture even after war and other attempts to destroy it.Footnote 70

Godwin's Political Justice (1793) alluded to Burke's traditionalist view of social life as people's membership in ‘little platoons’, or small class-based communities, but took it in a radically anarchistic political direction.Footnote 71 In Godwin's theory of the ideal, or ultra-minimal, state, people would live most freely and ethically in families and other small social units. Citizens would only come together occasionally to work out essential matters of over-arching government in localised representative bodies before returning to daily life in their little platoons.Footnote 72

Godwin represented this anarchist vision of peaceful social life with minimal government as a critical retort to Hobbes's pessimistic vision of a violent state of nature without government. Based on his experience of the English civil wars, Hobbes famously theorised in Leviathan (1651) that the lack of a sovereign with sufficient power to enforce the law would inevitably entail the dissolution of society and government into a state of war of each against all.Footnote 73 A good pupil of Locke, Godwin thought (contra Hobbes) that people were social by nature and could live peacefully in groups even without the oversight of government. Godwin took Locke's argument in the Second Treatise of Government (1690) about the state of nature in a more radical political direction.Footnote 74 True justice and happiness, Godwin argued, would be achieved by individuals in small communes without much government. Political Justice went so far as to theorise an inverse relationship between the amount of government and the capacity of people to deduce and perform the moral duties prescribed to them by the laws of reason. In other words, Godwin thought that the minimisation of government intervention was the political key to making people realise their ethical potential as duty-bearers towards others.

In The Last Man, Shelley represented this philosophical debate between Godwin, Burke, and Hobbes as a political allegory. When the plague enters England, the government is unprepared, and society begins to crumble. In the initial fearful stages of self-quarantine, people retreat into their homes, living in relatively peaceful isolation. Meanwhile, the government – abandoned by its elected populist leader Ryland, then saved by Adrian and Verney – attempts to help the poor, provide medical care, and prevent the spread of the plague by imposing trade and travel restrictions. This peacefully anarchistic stage of England's pandemic response reflects some of the communal ideals of Burke as refracted through Godwin's progressive theory of political justice.

But as the epidemic worsens in England, a more dangerous form of anarchy plagues the very basis of its society. Unburied bodies, panic, violence, invading forces, and apocalyptic cultists haunt the edges of Windsor Castle and weaken Adrian's republican government to the point that it finally collapses. This descent into levelling death and chaos is the final, Hobbesian, worst case scenario of England's failure to adequately respond to the existential threat of the pandemic.

Without a government to lead, Adrian and Verney round up the last survivors – a frail thousand – and flee to France. There anarchy is no better. With the rise of this plague-driven state of war within and across states, Shelley signals her agreement with Hobbes's view that the state of nature is ultimately a state of war. When there is a vacuum of power on a national or international scale, the abyss of anarchy opens to swallow society whole.

Hobbes gleaned this dour lesson from the English civil wars, a political tragedy the Shelleys knew well from Percy's reading aloud Hume's History of England in 1818.Footnote 75 Hume's History told the story of Sir Edmund Verney, an English aristocrat loyal to Charles I who died carrying the king's standard in the Battle of Edgehill in 1642.Footnote 76 His eldest son, Sir Ralph Verney, wrote an account of the Long Parliament and remained strategically neutral and diplomatic in his negotiations between the Royalists and the Cromwellians.Footnote 77 The Verney family held several estates, including one in Buckinghamshire, not far from where the Shelleys lived in Windsor in 1815–16 and in Marlow in 1817–18.Footnote 78 One wonders if Ralph Verney, a famous survivor of the English civil wars and the great plague of London of 1665–6, may have been an inspiration for Lionel Verney, the last survivor of a series of disasters caused by a cycle of war and plague.

Like Thomas Hobbes, Ralph Verney, and Emer de Vattel, Shelley's Lionel Verney is wary of the danger of a state of war on the national or international scale. But Mary uses the story of ‘THE LAST MAN’ to make a Vattelian point about peacefully closing the vacuum of power. As a post-pandemic ambassador of ‘the offices of humanity’, Verney models to himself and his readers how the international political void can and should be filled with a culture of friendly and hopeful diplomacy, which aspires to make peace over time with the whole world. This Vattelian diplomatic peace is governed by a ‘universalistic’ law (or obligation) of a ‘moral person’ (whether an individual or a state) to care for and protect the life and independence of oneself and others, especially the weak and vulnerable, across artificial borders of nation, culture, and species.Footnote 79 Verney acts on this diplomatic sense of obligation to care for the whole world when he refuses to succumb to despair and loneliness, and sets out with his dog and his books in search of a new community with whom to remake a planetary dystopia into a cosmopolitan utopia.

Shelley's post-apocalyptic legacies for existentialism, dystopian literature, and international thought

There is a trail of intellectual influences from Shelley to Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Stoker, Camus, Orwell, Butler, Atwood, Mandel and the modern existential, post-apocalyptic, and dystopian novel. The Last Man and the Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin's influential play A Feast in Time of Plague (1830) borrowed decadent elements from the Scottish playwright John Wilson's City of the Plague (1818) by depicting people dancing or hosting dinner parties amid pestilence.Footnote 80 Fyodor Dostoevsky adored Pushkin. In Notes from Underground (1864), he alluded to the poet-playwright's famously paradoxical image of raising a toast to the plague.Footnote 81 Dostoevsky pictured a man living alone in a basement, revelling in the darkness of human existence instead of seeking an escape from it through the delusions of post-Enlightenment liberal-utopian politics. This ‘underground man’, like Friedrich Nietzsche's ‘Last Man’ after him, are riffs on the post-apocalyptic literature of the era of the Napoleonic wars, popularised by Shelley's SF novels and Lord Byron's poem ‘Darkness’ (1816), which pictured the extinction of life after the death of the sun.Footnote 82

A classicist by training, Nietzsche turned towards the writing of a new form of existential literature and philosophy in a similar vein as Dostoevsky, whom he first read in 1886.Footnote 83 Although we do not know for certain whether he read Shelley, Nietzsche suggested his cultural grasp of Frankenstein's reworking of the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus. In Beyond Good and Evil (1886), he wrote, ‘He who fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster.’Footnote 84 This aphorism might be read as a philosophical abstract of the conflict at the heart of Shelley's first novel. Victor Frankenstein becomes a monster by fighting with his own monsters, internal and external – first, his perfectionistic psychological drive to create and dominate life, and then, his material creature made from this hubristic urge to become a tyrannical god.

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–5), Nietzsche used the figure of the ‘last man’ as the allegorical antithesis of his ‘superman’ or ‘overman’.Footnote 85 Unlike the hopeful Verney who dares to believe that other people have survived the global plague, Nietzsche's despairing last man brings about the destruction of himself and humanity by sinking into the depths of a corrupt and pointless nihilism. Nietzsche bewails the descent of most of modern mankind into a ‘monstrous’, beast-like state, and calls for the best of the rest of them to rise to the noble task of the ‘first man’ or ‘overman’: to take charge of reforming humanity as a whole by ascending to a higher level of individual virtue.Footnote 86 This superman/overman shares with Verney a future-oriented and poetic, empowered yet solitary posture, figured in Romantic painting of the nineteenth century as the lone woman or man looking over a sublime cliff or across a moonlit or sunlit horizon, made famous by the German artist Caspar David Friedrich.Footnote 87

The reception of Shelley and the representation of ‘The Last Man’ in art

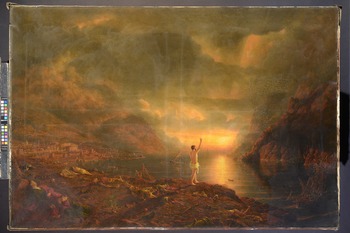

The most famous of the nineteenth-century artworks to directly represent the idea of the last man was a study and painting series (c. 1826, 1832, 1849) by the British Romantic artist John Martin (Figure 1).Footnote 88 Martin began the series during the year Shelley published The Last Man. He took inspiration from the public debates about the possibility of the end of humanity, reinvigorated by the publication of Thomas Campbell's short poem ‘The Last Man’ (1823, 1825) and Shelley's novel (January 1826).Footnote 89 Martin became famous for painting scenes of apocalyptic disaster, which, according to art historian Barbara Morden, influenced the Brontës and the Pre-Raphaelites.Footnote 90 Well connected in English society, Martin was friends with the gothic novelist, poet, and Member of Parliament Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who was in the social circles of Shelley and Godwin and corresponded with them extensively in the late 1820s and 1830s.Footnote 91

Figure 1. John Martin, The Last Man (1849), Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Martin wrote to Bulwer-Lytton in 1849 to thank him for sending his recently published poem, ‘King Arthur’. The poem drew explicitly from the language of both Campbell and Shelley's depictions of the last man as a seer overlooking a ruinous landscape, only to find hope on the horizon:

Bulwer-Lytton's verse nicely captures the post-apocalyptic ending of Shelley's The Last Man, with Verney steering his ‘phantom bark’ into an unknown future like a new-age version of Coleridge's ancient mariner. These lines inspired Martin as he completed his painting of ‘The Last Man’ for exhibition at the Royal Academy and Liverpool that year, in the midst of a cholera epidemic.Footnote 93 The canvas depicts a white-robed sage, raising an arm to greet a red sun, not a dead sun, over a stormy and desiccated landscape.

Bulwer-Lytton also corresponded with Thomas Campbell in the 1840s.Footnote 94 In London in 1823, Campbell had issued his hopeful Christian ‘evangelical’ poetic response to the bleak vision of the death of the sun and the extinguishing of life in Byron's ‘Darkness’, but it met little attention.Footnote 95 Republished in London to great acclaim in 1825, Campbell's poem ‘The Last Man’ sparked a public debate on apocalypse and human extinction that only gained steam with the publication of Shelley's novel in January 1826.

Returning to London from Italy in August of 1823, and supporting herself and her sole surviving child by writing for local publishers and periodicals, Shelley would have been aware of the controversy over Campbell and Byron's competing visions of the end times while she wrote The Last Man between the spring of 1824 and the winter of 1825. When the Shelleys were visiting the exiled poet in Geneva during the dark and stormy summer of 1816, Byron composed his great apocalyptic poem around the same time Mary noted in her journal that she had begun to write Frankenstein.Footnote 96 It was the ‘year without a summer’ when the climatic impact of the eruption of Mount Tambora caused skies to darken around the world.Footnote 97

In May of 1824, the night before she learned of the death of her friend Byron from sepsis near the field of the war of independence in Greece, Shelley confided to her journal that she knew what it meant to be ‘the last man’, with everyone she loved ‘extinct before me’.Footnote 98 Her distinctive use of the word ‘extinct’ suggests a profoundly personal and psychological link between the shock of the loss of individual life and the mourner's ascent to existential contemplation of abstract and absolute nothingness. In the next entry in her journal, Shelley noted how prescient she was. She was now, in fact, the last (and leading) literary woman in the second generation of British Romanticism. Campbell's poem, reissued in 1825, would have resonated deeply with her in the wake of the death of her closest living friend Byron, author of ‘Darkness’.

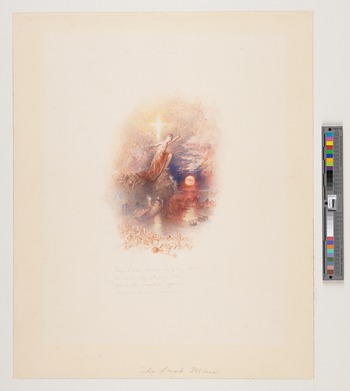

Indeed, the legacies of Campbell's poem for popular culture run deep throughout nineteenth-century Anglo-American art and music. In London, between 1826 and 1832, a comic play and a number of satirical cartoons and essays spoofed the concept of the ‘last man’ (and, after the publication of Shelley's thinly-veiled roman à clef, the ‘last woman’).Footnote 99 This international cultural hub also saw a serious tribute, the short opera scene ‘The Last Man’ (1826) with lyrics from Campbell's poem and set to music by William H. Callcott, performed four times in the same period.Footnote 100 In 1835, the best-known British Romantic painter J. M. W. Turner – whom Godwin took his daughter Shelley to visit in his studioFootnote 101 – illustrated an 1837 edition of Campbell's poems. It featured a watercolour of the last man as an angelic new Adam, guided by a golden cross in his leap of faith towards heaven over an orange-pink sun, which is setting, or perhaps rising, on the horizon (Figure 2).Footnote 102

Figure 2. J. M. W. Turner, The Last Man (1835), National Galleries Scotland.

The religious resonances of Campbell's poem turned the last man into a mainstream nineteenth-century icon of hope. Music publishers in London, New York, and Boston reissued Callcott and Campbell's 1826 opera scene ‘The Last Man’ from the 1840s through the 1870s.Footnote 103 In 1857, in Boston, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and New York, it was printed as part of a series ‘Sweet Songs for Sabbath Evenings’ for hymnals and churchgoers.Footnote 104 This popular sacred music, like Martin's painting, represented the last man in a prophetic manner, heralding not the nihilistic death of the sun but rather the sign of a brighter way of life to come. In the words of Campbell, as sung in the opera scene: ‘Yet prophet-like, that lone one stood, Saying, This spirit shall re-turn to Him That gave its heav'nly spark.’Footnote 105

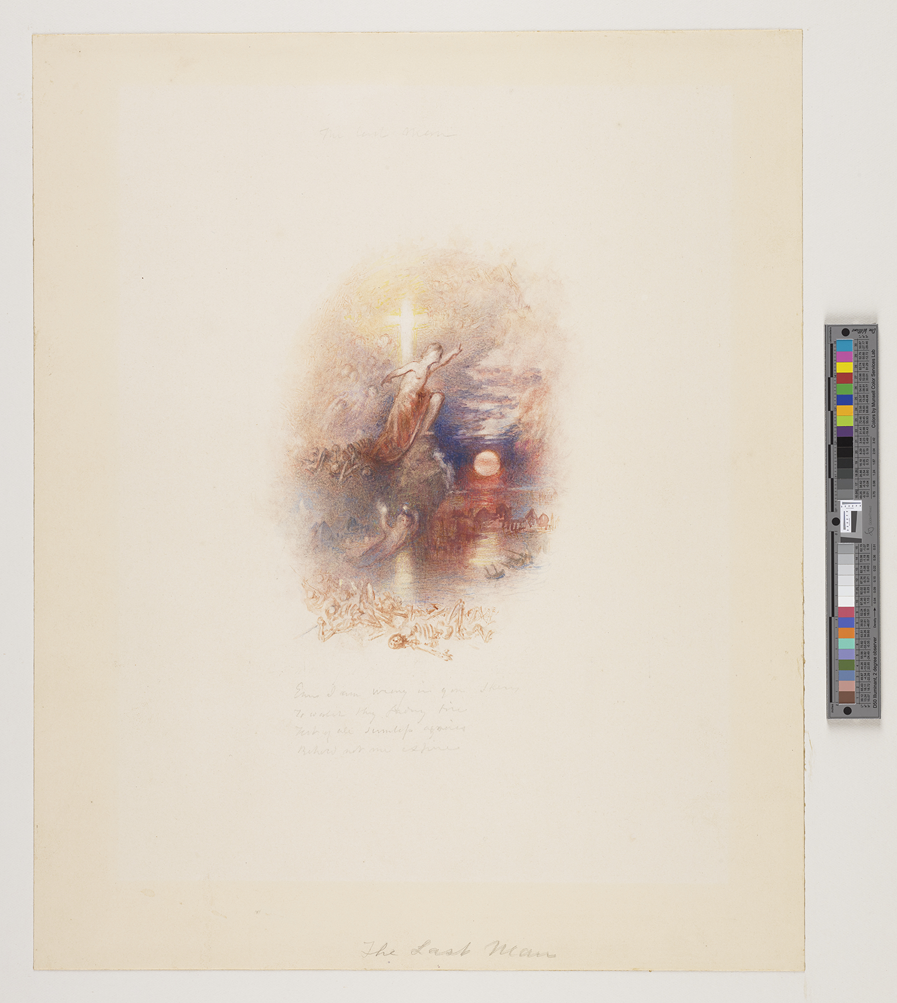

In this Victorian evangelical context, the Irish artist Robert George Kelly exhibited his painting The Last Man to critical appreciation in Birkenhead, England in 1886 (Figure 3):Footnote 106

Figure 3. Robert George Kelly, The Last Man (1886), Williamson Art Gallery, Birkenhead, UK.

Its dark yet dramatic canvas offers a vista of hope through its vision of an orange sunset (or sunrise) that illuminates a bare man half-dressed in white like Christ after the resurrection. Facing away from the viewer, he raises his hand towards the horizon as though to welcome the light into the darkness engulfing the world. In nineteenth-century European art and literature, Campbell, Shelley, Martin, Turner, and Kelly's iconic images of last men, alongside Nietzsche's superman, gesture towards a new post-apocalyptic future in which humanity resurrects itself in more positive and creative ways than ever seen before, despite the threat of extinction. These artworks depict a literal sunrise after humanity's sunset, as an affirmation that something does and will exist, even if we do not.Footnote 107

The reception of Shelley in post-apocalyptic and dystopian literature

Beyond her tantalisingly indirect connections to Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Martin, Campbell and other nineteenth-century creators of last men, Shelley directly influenced countless works of post-apocalyptic and dystopian literature. Among the most philosophically and politically significant are Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897), H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds (1897), M. P. Shiel's The Purple Cloud (1901), Alfred Noyes's The Last Man (1940), George Orwell's Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Albert Camus's The Stranger (1942) and The Plague (1947), Richard Matheson's I Am Legend (1954), Octavia Butler's Clay's Ark (1984) and Parable series (1993–8), Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (1985) and MaddAddam trilogy (2003–13), and Emily St. John Mandel's Station Eleven (2014). All of these novels use metaphors of plague to convey how the social pathologies and psychological contagions of political injustice are transmitted by monsters across boundaries of family and nation. These monsters may be literal bloodsucking, man-eating cannibals, or figurative vampires, who seek to dominate others through manipulative practices of mind control and physical torture. In twentieth-century dystopian literature, figurative vampires proved to be more effective than literal vampires in draining the life and humanity from society by taking the form of totalitarian states and conquering empires.

At the time of his death, Stoker owned a Victorian pocket-sized edition of Frankenstein, printed in the 1860s. Its superadded subtitle – ‘the Modern Man-Demon’ – eerily anticipated Stoker's depiction of Count Dracula as a monstrous hybrid of man and demon.Footnote 108 The shape-shifting vampire from Transylvania is less a person than an evasive spectral phenomenon or miasmatic disease that hovers around and possesses its hosts. Like an oppressive wave of plague spread by bats or rats, or even a violent poltergeist, Dracula takes on a variety of material forms and overtakes the most cutting-edge technology of the British empire – electric telegraphs and steam-driven international shipping – to target and prey upon his victims, reigning death and chaos across the thresholds of homes and states. The international and technological bent of Stoker's novel, in turn, may have influenced the leading dystopian novel of totalitarian political surveillance: Nineteen Eighty-Four.

On Christmas of 1919, the teenage Eric Blair (later known as George Orwell) gave a copy of Dracula – arrayed with garlic and an ornate crucifix – as a love-gift to his sweetheart Jacintha Buddicom.Footnote 109 His monumental works of dystopian fiction, Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), are concerned with the two dominant themes of Dracula and Shelley's SF novels before it. First, there is the political problem of cannibalism, real or metaphorical, by which people in power cruelly use or prey upon their fellow creatures in order to advance their own craven and even bloodthirsty interests. Secondly, there is the political problem of mind control, literal or figurative, by which people's worldviews are manipulated and tainted by the insidious belief systems of those in power.

While he was at boarding school in the 1910s, Orwell loved to read plague literature and speculative tales of epidemics and disease, including Edgar Allan Poe's plague allegory, ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ (1843) and H. G. Wells's novel The War of the Worlds (1897) and short story ‘The Country of the Blind’ (1904).Footnote 110 Wells's novel chronicled a cataclysmic alien infestation of Earth, stopped only by a pathogen for which the invaders lacked immunity. In the final chapter, Orwell would have encountered the narrator deliriously singing lines from Thomas Hood's satirical poem, ‘The Last Man’ (1826), when he discovers that the aliens have been defeated by the Earth's microbes. ‘The Last Man Left alive! Hurrah! The Last Man Left Alive!’ he chants, not realising that other people around the world have made the same gleeful discovery of their survival.Footnote 111 Wells may have encountered Shelley's Last Man, too, as part of his research into Hood's ironic response to the ‘last man’ trope of the 1820s. What we do know for certain is that Wells knew Frankenstein, for he directly referenced its title in the opening pages of the manuscript for his novel about making human-animal hybrids through science, The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896).Footnote 112

Unlike Wells, we do not have direct evidence that Poe read Shelley, but there is a consensus that he alluded to the final sentence of Frankenstein in the last lines of one of his earliest published stories, ‘Ms in a Bottle’ (1833).Footnote 113 That same year, he might have acquired from his publishers their new dual release of the first American edition of The Last Man with Frankenstein.Footnote 114 As with Poe, we also do not know for certain if Orwell read Shelley's novels. But we do know that Orwell praised the ‘lost art’ of her journals – the basis of her roman à clef, The Last Man – in 1944, and that the original title for Nineteen Eighty-Four was ‘The Last Man in Europe’.Footnote 115 He may have been directly referencing Mary Shelley's novel when he had the hero Winston Smith described as ‘the last man’ as he is tortured for his belief in love by O'Brien, the merciless agent of the totalitarian regime.Footnote 116

While reviewing English Diaries of the Nineteenth Century in 1944, Orwell had encountered a three-page transcript of Mary Shelley's journals, covering 14–15 May 1824. It was on 14 May that she invoked the concept of the last man: ‘The Last Man. Yes, I may well describe that solitary being's feelings: I feel myself as the last relic of a beloved race, my companions extinct before me.’Footnote 117 James Aitken, the editor of English Diaries of the Nineteenth Century, underscored the term ‘The Last Man’ with a footnote that identified it as the ‘Title of a novel she was writing’.Footnote 118 As the research head of the Orwell Society, L. J. Hurst, has pointed out, ‘the key words “last man” and “extinct” also appear in O'Brien's one-paragraph address to Winston’:

‘If you are a man, Winston, you are the last man. Your kind is extinct; we are the inheritors. Do you understand that you are alone? You are outside history, you are non-existent.’ His manner changed and he said more harshly: ‘And you consider yourself morally superior to us, with our lies and our cruelty?’Footnote 119

These neat parallels make one wonder if Orwell paid homage not only to Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's existential meditation on the bleak sense of extinction that comes after the absolute loss of love, but also to the last two initials of her pen name, by calling the tragic hero of Nineteen Eighty-Four – who is tortured by the state for having a love affair – ‘Winston Smith’.

Malcolm Pittock made the case that Orwell may have changed the title from The Last Man in Europe to Nineteen Eighty-Four, just before it went to press in late 1948, due to the fact that Alfred Noyes, a well-known Catholic conservative writer, had recently published a popular novel titled The Last Man. Pittock did not explore whether Noyes appropriated the title from Shelley's novel or other representations of ‘the last man’, but rather focused on unearthing parallels between the plot of this 1940 post-apocalyptic novel and Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.Footnote 120 Its parallels with Shelley's plague novel and its closest adaptation, Shiel's The Purple Cloud, are far more obvious.

Noyes's The Last Man is about a global war that seemingly leaves one man alive only to find a female survivor with whom he falls in love, much like Shiel's romantic twist on Shelley's existential thought experiment. Before the catastrophic war, Noyes depicts the world's nations split into two rival leagues or factions. They use bioweapons that spread lethal diseases across borders, harming both their enemies and themselves. Then the ‘two sides’ mutually deploy a more effective and supposedly ‘secret’ and ‘last resort’ doomsday weapon that sends ‘all-pervasive’ and ‘ethereal waves’ to stop the ‘beating of the human heart’.Footnote 121

Noyes began his post-apocalyptic novel in medias res. The narrator compares his incredible story of survival with nineteenth-century ‘Poems and works of fiction’ about the ‘last man’.Footnote 122 The narrator alludes to the plotlines of two of the best-known plague novels in this tradition, Wells's The War of the Worlds and Shiel's The Purple Cloud, as well as the ‘dying sun’ imagery of Byron's ‘Darkness’, before he recounts how he in fact endured a war-driven near-extinction event and found love despite it all.Footnote 123

In 1944, Orwell described Noyes's poetry as ‘completely spurious bombast’ and reviewed his 1942 novel The Edge of the Abyss.Footnote 124 He judged the story so ‘silly’ and ‘incoherent’ as to not merit rehearsal, even as it raised a serious question: will rising amorality lead to the ‘destruction’ of ‘Western civilization’?Footnote 125 If Orwell also deigned to read Noyes's The Last Man, he was yet again exposed to the tradition of post-apocalyptic literature rooted in the 1820s debates on ‘the last man’ to which Shelley contributed the major plague novel.

Nineteen Eighty-Four, like Shelley's and Noyes's extended riffs on the ‘last man’ theme, is as much a war novel as it is a novel of dystopian international politics. Writing in the wake of the bombings of London during the Second World War, Orwell knew first-hand the terror of living under the constant threat of destruction. Indeed, his wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy Blair died in 1945 after a surgery intended to resolve her poor health, which had been exacerbated by the grief and tension of wartime. In 1950, Orwell also died young from the contagion of tuberculosis that he contracted as a child and had crippled him for months on end as an adult. Perhaps inspired by his wife's 1934 poem ‘End of the Century, 1984’, which imagined what her high school would be like fifty years in the future, Orwell's greatest novel is set in a dystopian Britain of the late twentieth century.Footnote 126 No longer a sovereign nation-state governed by an elected parliament through the consent of its citizenry, Britain has been subsumed under the empire of Oceania. Constantly at war with other superstates, Oceania treats Britain – known as ‘Airstrip One’ – as a mere landing strip for its airborne weapons.Footnote 127

The reception of Shelley and the rise of the existential novel

While in Paris in 1945, Orwell tried to meet Camus, a fellow journalist and critic of fascism. He later sent Camus a copy of the French edition of Animal Farm, a fable about how authoritarian and totalitarian regimes cannibalise their own.Footnote 128 Camus's two great existential novels from the 1940s, The Stranger and The Plague, share uncanny thematic resemblances to both Frankenstein and The Last Man.Footnote 129 The suicidal protagonist of The Stranger, Meursault, has often been compared to the Creature.Footnote 130 The characters share angst-ridden social isolation, the utter failure to thrive in emotional and familial relationships, and sudden descents into murderous crime because of the tragic sense of the absurdity of existence.

Although The Plague does not concern a pandemic but rather a localised epidemic of the bubonic plague, it follows both Animal Farm and The Last Man in treating contagion as a metaphor for how political ideologies (fascism, imperialistic war) manifest as social diseases that drain a society of its capacity for humaneness. And like Shelley's SF novels, Camus's existential narratives explore the psychological state of a lonely survivor of personal or political disaster. Dr Rieux, the narrator of The Plague, is a survivor like Verney who lives to chronicle the implosion of a human community. Both existential survivors write journals that warn future readers of the danger of the resurgence of the social diseases of conflict, domination, and despair.

The fact that we still read their plague narratives, in their original and artistically adapted forms, suggests that Shelley and Camus shared a paradoxically yet contagiously hopeful existential outlook. Despite the darkness of their epidemic literature, both existential writers leave open the possibility of delivery from the disasters of the past to a new and unknown, post-apocalyptic blank slate. Humanity might then have a second chance to realise its potential for what had eluded them before: whether it is freedom or love, happiness, or peace.Footnote 131 Before he died in a car accident in 1960, Camus titled his last unfinished novel – published by his daughter in 1994 – The First Man.Footnote 132 One wonders if this conceptual reversal of the title of Shelley's pandemic novel signals his awareness of The Last Man and its many legacies in twentieth-century cinema and literature.

A reader of both Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, Camus was familiar with their existentialist ideas of ‘the last man’ and ‘the underground man’. In Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground (1864), the narrator's unforgiving sense of the meaninglessness of existence drives away the one woman in his life, leaving him alone in a dark basement. This ‘underground man’ prefigured both Nietzsche's ‘last man’ as well as Camus's Meursault.Footnote 133 All three archetypes of the modern existential protagonist tie back to Shelley's SF novels and their sources in eighteenth-century English and German literature. Camus and Shelley explicitly based their plague novels on Daniel Defoe's tale of solitary woe under quarantine lockdown in A Journal of the Plague Year.Footnote 134 Frankenstein's Creature reads and identifies with Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). And in his 1942 essay on his philosophy of the absurd, The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus revealed his deep reading in the works of Goethe, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche.Footnote 135 Through this intertextual overlay of influences, the idea of the last known survivor of a wider catastrophe – living alone in a hovel, basement, or bunker – has become a predominant existential trope of modern literature.

Matheson's horror-SF novel I Am Legend was pivotal for the development of the mid-century, postwar iteration of post-apocalyptic literature.Footnote 136 It effectively combined the gothic plot lines of Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Last Man with the existentialist ideas of Camus, Nietzsche, and Dostoevsky. Matheson's proximate source for adapting the plot of The Last Man was M. P. Shiel's novel The Purple Cloud (1901) about a toxic gas that instigates humanity's self-destruction through war and other conflict.Footnote 137 In a romantic version of the aporetic ending of The Last Man, Shiel had the last man abandon his misanthropy when he stumbles upon a female survivor and seer, buried in the ruins of Constantinople, with whom he falls in love.

Blending elements of Stoker, Shiel, and Shelley as refracted through filmic versions of their novels, Matheson imagined a post-apocalyptic America in which all but one human has been turned into a vampire by a bioengineered plague. This lone man, Robert Neville, quarantines himself in a bunker to fight off the invaders. Yet he ultimately realises that he is the aberration or monster, not the vampires, for he is the ‘last of the old race’ of humans.Footnote 138 Matheson's novel was adapted for the screen as The Last Man on Earth (1964), and later as I Am Legend (2007), starring Will Smith. The 1964 film almost single-handedly spurred the zombie apocalypse genre in film and television, led by the directorial work of George Romero.Footnote 139

In the interwar period, feminist SF gained traction, especially in the post-apocalyptic mode. The art critic Helen Sunderland likely authored the anonymous short story, ‘The End of the World’ (1930), which imagined a ‘plague’ after the ‘third World War’ that takes ‘the males of every nation’, leaving women to mourn the death of ‘the Last Man’ and the eventual demise of the human species.Footnote 140 While a young poet in the 1950s and 1960s, Margaret Atwood was a devoted reader of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and Shelley's Frankenstein.Footnote 141 Atwood's feminist dystopian fictions from the Handmaid's Tale and MaddAddam series are replete with monstrous imagery of blood, betrayal, cannibalism, and the ripple effects of toxic romantic and familial relationships.Footnote 142 Atwood's handmaid is Creature-like in her diaristic recording of her social isolation and deprivation as a sexual slave forced to work for a Puritanical theocracy in the early twenty-first century.

The biracial SF writer and critic Samuel R. Delany called Octavia Butler the leading black SF writer after Shiel.Footnote 143 A distinctive element of Butler's style was to draw upon the monster and vampire imagery of post-apocalyptic fiction in the literary vein of Matheson, Stoker, and Shelley. Set in 2021, her novel Clay's Ark chronicles the dangerous outbreak of a highly infectious alien microorganism after a spaceship crashed in the desert with one contagious survivor.Footnote 144 This last man deliberately infects other humans who mutate into blood-drinking, cat-human hybrids.

Also set in the twenty-first century, Atwood's prescient MaddAddam series envisions the invention of a CRISPR-like technology that would allow for the making of pig-human hybrids (such as scientists in fact began to make in petri dishes in 2017).Footnote 145 In this dystopian triptych, a nihilistic leader in the corporatised pharmaceutical industry cynically unleashes a bioengineered plague in the form of a sexual enhancement pill.Footnote 146 While his express purpose is to destroy humankind, two women survive him who bring humanity back from the brink of extinction.Footnote 147

Atwood's work inspired Butler's Parable series and Mandel's Station Eleven: especially their now-iconic stories of ‘last women’ who, like Mary/Verney, find the strength to survive a devastating series of personal and political disasters to sustain hope of a better future. In The Parable of the Sower, Butler presents the diaristic story of a young African-American woman, Lauren Oya Olamina.Footnote 148 In the year 2024, she escapes the breakdown of her impoverished and violent Los Angeles community by disguising herself as a man and hitting the road into the anarchistic world beyond the city walls. In the sequel, The Parable of the Talents, Olamina – a bit like Mina, the female lead of Dracula – uses her superhuman capacity for identifying with other people's thoughts and feelings to fight the social diseases of her time and work towards a new, post-apocalyptic world of peace and justice to be realised on another planet.Footnote 149

Mandel's Station Eleven is poignant to read during the time of COVID-19, as it foresaw that a lethal flu-like pandemic could be unwittingly and swiftly transmitted via international air travel. Mandel directly referenced the existential philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre throughout her post-apocalyptic plague novel set in the near future of the twenty-first century. While Sartre pessimistically argued in his play No Exit (1944) that ‘hell is other people’, Mandel has her young heroine Kirsten survive the state of war left in the wake of the Georgia Flu to realise that true hell is both ‘a world with almost no people in it’ and ‘the absence of people you long for’.Footnote 150

Like a ‘final girl’ survivor in a late twentieth-century slasher horror film, Kirsten narrowly escapes a brutal execution by a false prophet of doom when one of his abused followers turns on him to save her before committing suicide with the same gun.Footnote 151 Akin to Verney equipped on his ship with the works of Shakespeare and Homer, Kirsten's love of literature and its power to imagine a more hopeful future is what sparks this act of supererogation by a stranger. As she recites lines from her favourite comic book, Station Eleven, to the mad cult leader who also happens to own one of the few surviving copies, Kirsten distracts him long enough for his rebel sentry to finally revolt against the tyrannical ideologue. In the final scene of the novel, Kirsten gives her copy of the comic book to an airport museum established to preserve the vestiges of humanity's pre-pandemic past. Then she sets out to discover the mysterious source of the electric lights that have just been lit over the southern shore of Lake Michigan.

Mandel, like Atwood, writes dystopian fiction in the more hopeful and cosmopolitan mode of Shelley and Butler than in the dark and cynical mode of Orwell and Camus. This may be due to these women writers’ concerted bridging of a variety of gendered and international perspectives in their novels. A lifelong environmentalist, the Canadian Atwood has used her fiction to explore social justice issues raised by the melting Arctic, the uncontained AIDS epidemic, legal attempts to strip women of reproductive rights, and the corporatisation of bioengineering worldwide.Footnote 152 Now a New Yorker, Mandel came of age in Canada during the early twenty-first-century wave of SARS that hit Toronto due to traffic through its major international airport.Footnote 153

Conclusion: Literary IR from the last man to the final girl

Almost two centuries before Atwood, Butler, and Mandel shaped the contemporary field of feminist poliscifi, Shelley's seeming powers of augury likewise arose for deeply personal reasons with universal resonance. As a young English woman, travelling through Italy with her husband and children, she experienced an epidemic of tragedies on a depth and scale that most people could not bear. The original ‘last Woman’, or final girl who outlasts them all, Shelley's emotional and intellectual resilience in the face of the many plagues upon her family is what made her a visionary and generative SF novelist, existential writer, and political philosopher of pandemic and other artificially-made disasters.Footnote 154

It is to Shelley that we owe the diverse evolution of the modern existential, dystopian, and post-apocalyptic literary traditions – especially the hopeful feminist outlooks of Atwood, Butler, and Mandel – and their philosophical roots in Western international thought from Thucydides to Vattel. By reclaiming her within this feminist ‘counter-archive’ of poliscifi, we reveal how post-apocalyptic and dystopian literature can build pragmatic, creative, optimistic, and emotionally compelling bridges between existentialism and IR.Footnote 155 This interdisciplinary, bridge-building exercise in Literary IR is crucial for rectifying two long-standing biases of these critical areas of philosophy and political science: (1) gender prejudice against the value of women's contributions to and perspectives on existential questions and international politics, and (2) a pessimistic orientation towards politics and the human condition that obstructs the hope and love necessary to move forward through globally impactful disasters of our own making.

Acknowledgements

I presented an early version of this article on a panel on Existentialism in IR at the 2021 virtual BISA meeting, and benefited tremendously from the comments from the Zoom audience. I would like to thank the editors of this Special Issue and organisers of the aforesaid panel, Cian O'Driscoll, Andrew Hom, and Liane Hartnett, and the editor of the Review of International Studies, Richard Devetak, for arranging the peer reviews of the manuscript which led to its final form. I would also like to thank the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, and the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at Notre Dame for their generous support of my archival work during the precarious research period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, a number of my colleagues in The Orwell Society played crucial roles in helping me to trace Shelley's legacies for dystopian and post-apocalyptic literature: Liam Hunt, Dione Venables, Les Hurst, and David Armitage.