Jeffrey L. Dunoff and Mark A. Pollack's article is an important and very welcome contribution to the discussion about judicial values. The authors argue that with respect to judicial independence, transparency, and accountability “judicial systems face inherent trade-offs, such that any given court can maximize two, but not all three, of these features.”Footnote 1 In our eyes, the article's most important contribution is its holistic view: it shows why these three judicial values can only be understood in their interconnectedness. It is, for instance, not meaningful to make a statement about the correlation between transparency and independence without also taking accountability into the equation. This is because the effect of transparency on independence can only be understood if information about judicial accountability is at one's disposal. In the past, these judicial values have often been analyzed in an isolated manner, thereby leading to wrong conclusions. The Judicial Trilemma will hopefully help in shifting the discourse from isolated to holistic views on independence, transparency, and accountability. Moreover, Dunoff and Pollack lay the groundwork for a meaningful normative discussion of these three judicial values. Any debate about how to structure (international) courts should henceforth take Dunoff and Pollack's holistic view as a basis for discussion.

While we agree with how the logic of the Trilemma works, we shall argue that Dunoff and Pollack's definition of the concept of judicial independence is too broad and too narrow at the same time. Moreover, we will elaborate on the normative preferences that the authors touch upon and make a proposal for an alternative graphic representation of the Judicial Trilemma.

Judicial Independence and Impartiality

Article 21(3) of the European Convention on Human Rights mentions judicial impartiality as a criterion for office, as do several other statutes of international courts.Footnote 2 However, impartiality only figures marginally in Dunoff and Pollack's article. Instead, it seems that they partly include it in the definition of the value of independence. Judicial independence is defined in The Judicial Trilemma as “the freedom of judges to decide disputes upon the facts and the law, free of outside influences such as the preferences of powerful states.”Footnote 3 Furthermore, Dunoff and Pollack consider judicial independence crucial both “for its own sake” as well as a means to an end.Footnote 4 They thus approvingly quote John Ferejohn stating that judicial independence guarantees that “judges [can] be autonomous moral agents, who can be relied upon to carry out their public duties independent of venal or ideological considerations.”Footnote 5

In our view, this understanding of independence is too broad. A narrower and more precise definition of independence would be: “the freedom of judges to decide disputes free of improper outside influences.” Judicial independence cannot guarantee that judges decide disputes only upon the facts and the law, without any ideological considerations. It is true that an independent judge will not be influenced by ideological convictions of other actors. However, even a highly independent judge might still apply the law through the lens of his own ideological views, which he cannot simply set aside. Therefore, an independent judge is not free to decide disputes solely upon the facts and the law, thereby discarding all ideological considerations. Judicial independence only solves one aspect of the problem of law application in an ideology-free way. In other words, judicial independence is merely a necessary but not a sufficient condition of judicial impartiality.

The argument that even an independent judge is not free to solely apply the law and the facts is based on the conviction that impartiality cannot fully be achieved. Is this a heretical belief, given that most statutes of international courts require judges to be impartial? We think that it is not, since impartiality can only be meaningfully understood as an ideal that judges ought to aspire to. Judges should try to decide on the basis of objective criteria and not to be guided by biases of any kind. However, the existence of a fully objective and nonbiased view is an illusion. Even when trying to be objective, one inevitably interprets the concept of objectivity. This, in turn, like all forms of knowledge, is dependent on our perspective, which depends on such factors as culture, language, history, and context.Footnote 6 Moreover, the attempt in good faith to be impartial is less difficult in certain areas than in others. The more conscious one is about one's biases, the easier it is to set them aside. The biases that one is not even aware of are probably the hardest to discard. If judges are, for instance, aware of which of their views are influenced by their religious beliefs they will have less difficulty in setting them aside. Fortunately, it is easiest to seek a relatively impartial view in cases where it is most needed, namely when a party to the dispute has a clearly different background than the judge. As an illustration, a judge of Christian faith deciding a case concerning religious feelings of a Muslim family will without difficulty be able to recognize the difference between his or her religious beliefs and the ones of the Muslim family. Therefore, the judge can attempt to consciously isolate and discard certain beliefs that might affect his or her impartiality. However, the task is more challenging in cases where a judge is not even aware of his or her biases, such as beliefs that he or she thinks are “natural” or simply “reasonable.” Since it is impossible for judges to be aware of all their biases, impartiality cannot fully be achieved. Hence even an independent judge is not fully free to decide disputes solely upon the facts and the law in an objective way. Therefore, the concept of judicial independence should not be understood to include impartiality.

Additionally, the definition of independence used in The Judicial Trilemma is not only too broad but also too narrow. If independence is defined as “the freedom of judges to decide disputes upon the facts and the law, free of outside influences such as the preferences of powerful states,”Footnote 7 it excludes appropriate outside influences. Therefore, the definition of independence should read “the freedom of judges to decide disputes free of improper outside influence.” Improper here denotes influence other than that gained through persuasive legal argumentation by a counsel, a relevant legal authority, other judges on the bench, or an amicus curiae.Footnote 8 If any outside influence on a judge would diminish his or her independence, he or she could not hear legal arguments by anyone while trying to remain fully independent. Moreover, influence is improper if it is direct, i.e., if it refers to particular decisions rather than diffuse influence over the judge's general view on the law and moral reasoning—such as achieved by his parents, former teachers, colleagues, etc.Footnote 9 Theodor Meron made the point that “judges are not empty vessels that the litigants fill with content.”Footnote 10 Instead, all judges are influenced by the values they grew up with. Socialization in the country of origin will inevitably shape the legal and moral understanding of a judge and thus also influence him or her during the time on the bench. However, such influence is not improper and does not diminish the judge's independence. Given these considerations, Dunoff and Pollack's definition of judicial independence is too narrow.

Normative Preferences

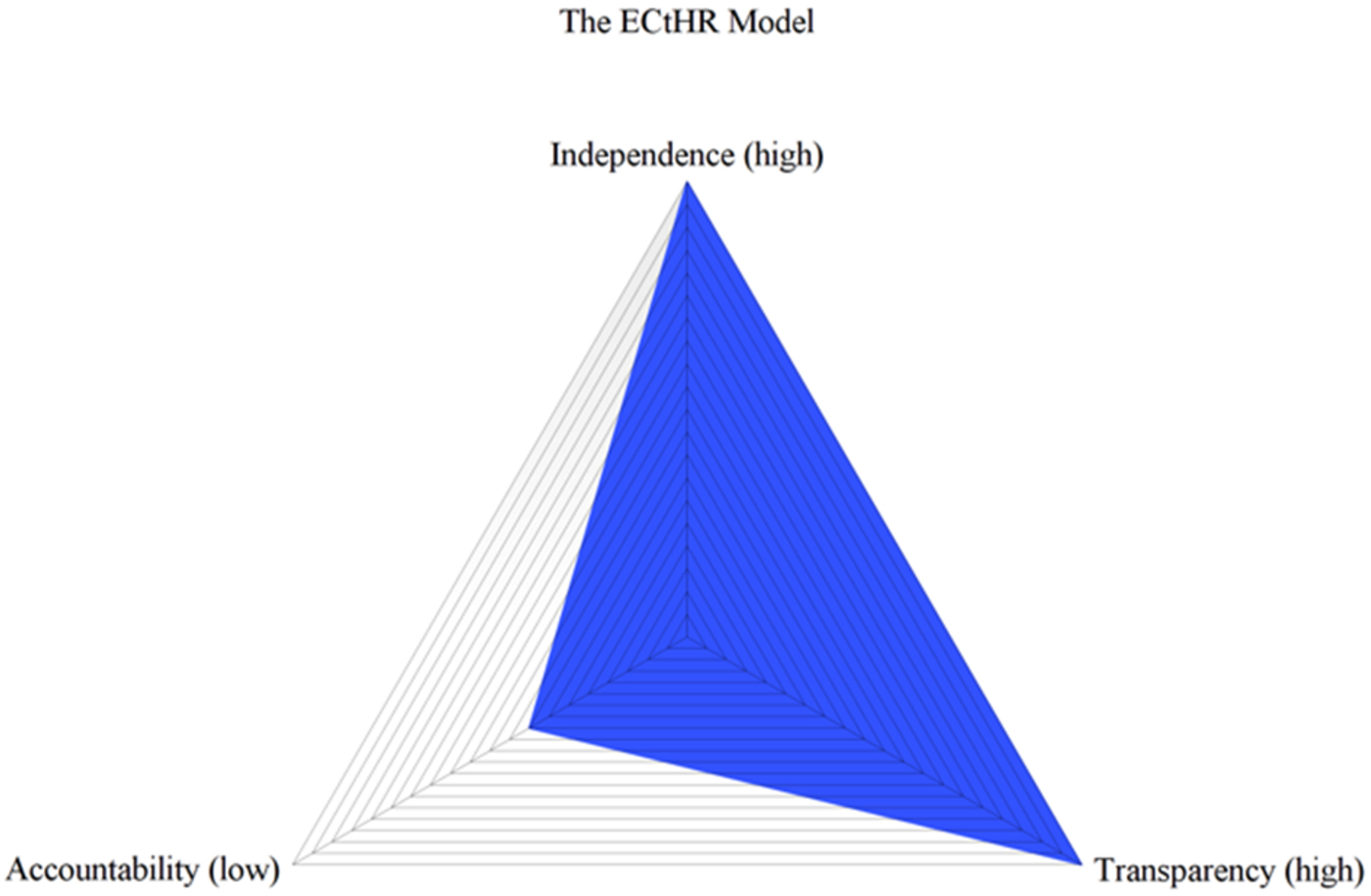

Dunoff and Pollack's main goal is to explain the Judicial Trilemma's underlying logic without taking a stance on the relative importance of the three judicial values.Footnote 11 However, in a short section at the end the authors present their normative preferences: they are convinced about the importance of independence, think that concerns with transparency are exaggerated, and are of the opinion that a lower degree of accountability is tolerable.Footnote 12 This is why they endorse the approaches taken by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the International Criminal Court (ICC), which combine high levels of independence and transparency with low levels of accountability.Footnote 13 The authors do this while being aware that there is no “universally valid ‘best’ approach to the Trilemma that is appropriate for all courts at all times.”Footnote 14 We agree with these findings but think that the approach taken by the ECtHR could still be improved. This should not be considered as a critique of Dunoff and Pollack's article, since we instead elaborate on the normative considerations that build upon the logic of the Trilemma.

It is indeed a welcome development that member states of the Council of Europe made a choice to promote judicial independence by giving up renewable terms. However, independence at the Strasbourg Court is far from “maximized”Footnote 15 (whatever that term means). Instead, judicial independence at the ECtHR can be considered relatively high. One important reason for this is that judges only enjoy functional immunity. Most judges occasionally leave Strasbourg for a trip to their home country. During these times, while mostly acting in their private capacity, it is possible to prosecute them for an offense unrelated to their activity at the Court. It is obvious that the possibility of a prosecution is important, given that judges should not be able to act as they wish while serving on the bench. However, there is also a danger that such prosecutions would be used in order to intimidate judges and thus to diminish their independence. Hence the question is whether it is more regrettable if judges can break the law without facing the consequences or if the same judges are dependent on their own state. The latter could mean that in several cases judges would be inclined not to find a violation of an appellant's human rights where they should have done so. It seems to us that this is more regrettable, given that impunity for human rights violations is likely to be graver than impunity for offences that judges might commit, which are rare and usually of a much less serious nature. In light of these considerations, it would be a welcome development to strengthen the immunity of ECtHR judges.

Another issue is the immunity accorded to judges after the end of their mandate where they are immune only “from legal process in respect of words spoken or written and all acts done by them in discharging their duties.”Footnote 16 Some former judges experienced pressures related to their activity on the bench.Footnote 17 Taking such concerns into account, the Plenary Assembly in its Resolution 1914 (2013) stated that ECtHR judges and their families should be accorded “diplomatic immunity for life.”Footnote 18 This would shield former judges from prosecution unless the Plenary Court decided that such action was unrelated to his or her activity on the bench.Footnote 19 We are of the opinion that such a safeguard ought in principle to be supported. However, it should not apply to all kind of offences, since certain prosecutions are clearly not politically motivated, i.e., not conducted in order to retaliate against former judges for what they did during their mandate in Strasbourg. In such situations, it would be unreasonable and inefficient if a duty existed to first address the Plenary Court.

Thus, while we concur with Dunoff and Pollack that the ECtHR, by comparison with the other international courts highlighted in the article, deals with the Judicial Trilemma in the most meaningful way, this is not to say that it is ideally structured. Instead, the level of judicial independence at the Strasbourg Court is relatively high but should be further increased by strengthening judicial immunity. It is promising that states seem to be convinced of the importance of judicial independence and are willing to structure international courts accordingly, as the reform of the ECtHR and the establishment of the ICC show.

Graphic Representation

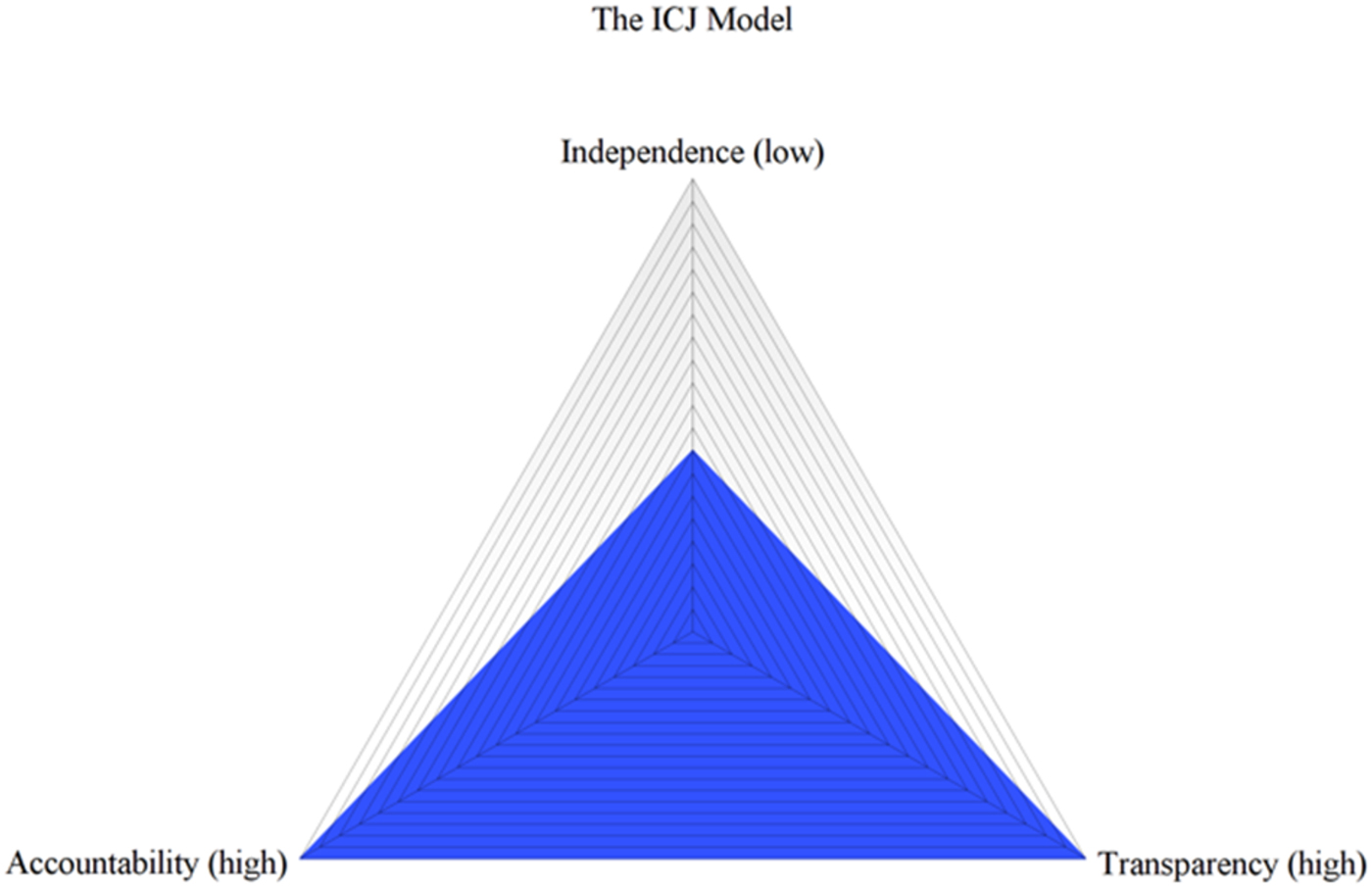

Dunoff and Pollack elaborately and convincingly explain the underlying logic of the Judicial Trilemma. Unfortunately, the Trilemma's graphic representation is less convincing. The Trilemma itself as well as the different ideal types are always represented with the same equilateral triangle. While the first use of this graphic representation still helps the reader to better understand that three values are at stake which are all somehow connected, its usefulness sharply decreases when used subsequently. The only differences between these triangles are their subtitles, which explain whether independence, transparency, and accountability are high or low. However, if only the subtitles are able to make the triangle understandable, why bother with the graphic representation at all? Given that illustrations are useful for the reader's concentration, especially in very long papers such as The Judicial Trilemma, we propose to adjust them. They could, for instance, be represented in a triangle where the colored surface does not reach all three vertices. With such a graphic representation, the diverse ideal types would look different, which would help the reader to better understand the logic of “pick two, any two.”

Concluding Remarks

The comments in this response should not distract from our conviction that The Judicial Trilemma is a highly useful contribution to understanding the functioning of (international) courts. It should be widely read by the academic community as well as by diplomats and international civil servants, given that it ought to serve as a basis for future reforms and the establishment of new international courts.

Target article

The Judicial Trilemma

Related commentaries (6)

Independence and Impartiality in The Judicial Trilemma

Independence at the Top of the Triangle: Best Resolution of the Judicial Trilemma?

Introduction to Symposium on Jeffrey L. Dunoff and Mark A. Pollack, “The Judicial Trilemma”

Systemic Judicial Authority: The “Fourth Corner” of “The Judicial Trilemma”?

The Application of “The Judicial Trilemma” to the WTO Dispute Settlement System

The Judicial Trilemma visits Latin American Judicial Politics