Context and literature review

The English Higher Education discourse on the ‘achievement gap’ between white and African, Asian and other Minoritised group (AAMG)Footnote 1 students, particularly undergraduate first-degree outcomes (Equality Challenge Unit, 2018), has been a blessing and a curse. It has been a blessing in raising sector awareness of race inequality in degree outcomes (Stevenson, Reference Stevenson2012), as well as incentivising individual institutions to draw up action plans to address their own race ‘achievement gaps’ (Bhopal and Henderson, Reference Bhopal and Henderson2021). However, the ‘achievement gap’ discourse has also been a curse as it has persisted in reproducing deficit understandings and perceptions of AAMG students (Madriaga and McCaig, Reference Madriaga and McCaig2019). Deficit thinking within an education context assumes that students have limitations in facets such as cognitive, motivational and other factors that lead to underachievement. Unfortunately, this deficit perception is the majoritarian narrative (Solórzano and Yosso, Reference Solórzano and Yosso2002), the dominant narrative, that informs policy and practice.

This majoritarian narrative has unfortunately taken hold in much policy-making in the English Higher Education sector. This is due to a hands-off approach from the state. There is equality legislation, such as the Equality Act 2010, to ensure people from AAMG have equal access and opportunities. However, even twenty years after the MacPherson Report, institutional racism endures in English education (Gillborn et al., Reference Gillborn, Demack, Rollock and Warmington2017). The higher education sector is seemingly divided, where the presence of AAMG students is more visibly represented in ‘lower status’ rather than ‘prestigious’ universities (Boliver, Reference Boliver2013; McCaig, Reference McCaig2018). Currently, the higher education regulator, the Office for Students, has taken a laissez-faire approach towards addressing racial inequalities in the sector. Although the Access and Participation Plans (APP) increase the documented narratives forwarded by Higher Education Institutes (HEIs) covering aspects of race, there is still an absence of being held to account for the continuous racial inequalities that exist within HEIs. The regulator, as of yet, has not suggested any penalties, legal or financial, to those institutions with persistent racial gap inequalities. However, it has released information to the public, listing institutions with the biggest gaps in degree outcomes between ‘home’ British black (inclusive of those categorised as British African and British Caribbean) and white students (Adams, Reference Adams2019).

With the regulator’s hands-off approach, individual HEIs are left to themselves to determine the extent of tackling their own racial inequities, particularly among staff and the student body. There is a colour-evasiveness (Annamma et al., Reference Annamma, Jackson and Morrison2017), an avoidance of explaining persistent race inequalities with institutional racism, and white supremacy throughout the education sector. This is mostly done under the banner of setting an inclusion agenda rather than addressing racism head-on (see McDuff et al., Reference McDuff, Tatum, Beacock and Ross2018; McDuff et al., Reference McDuff, Hughes, Tatum, Morrow and Ross2020). The colour-evasiveness of the inclusion agenda to address race inequalities and inequities leaves white supremacy and the legacy of colonialism unmarked. Whiteness pervades, casting the cultural differences of AAMG students to the side as deficits to learning.

To counter this majoritarian, colour-evasive narrative, critical race theory (CRT) is foregrounded here. CRT emerged out of US legal scholarship (Matsuda, Reference Matsuda1987; Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1991; Bell, Reference Bell1992). It has then crossed disciplinary boundaries and entered education via Ladson-Billings and Tate’s (Reference Ladson-Billings and Tate1995) seminal paper. There are core central tenets of CRT work in inclusive education of challenging notions of education being neutral and meritocratic. Centralising the experiential knowledge of CRT researchers opposes the distortion of AAMG experiences which foregrounds intersectionality as race and racisms (Solórzano and Yosso, Reference Solórzano and Yosso2002: 25-27). Building on this tradition, the likes of Doharty (Reference Doharty2018), Gillborn (Reference Gillborn2008), Joseph-Salisbury (Reference Joseph-Salisbury2019), Rollock (Reference Rollock2012), and Sian (Reference Sian2019) have advanced CRT work in education within the English context.

Out of CRT in education, the work of Yosso (Reference Yosso2005) and the contribution of cultural wealth has come to the fore as a counter-narrative to the colour-evasive narrative which heralds the beauty, the wealth, the cultural and linguistic differences that AAMG students bring to a classroom. This emphasis on cultural wealth is juxtaposed to Bourdieu’s capitals that can reproduce deficit perceptions of AAMG students and simultaneously be race-evasive (Wallace, Reference Wallace2017). This emphasis on ‘cultural wealth’ reflects the lineage of pedagogical approaches to ‘cultivate genius’ among AAMG students (Muhammad, Reference Muhammad2020), such as culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, Reference Ladson-Billings1994), culturally-sustaining pedagogies (Paris and Alim, Reference Paris and Alim2014), reality pedagogy (Emdin, Reference Emdin2016), and abolitionist teaching (Love, Reference Love2019). Many of these approaches centre the lives of AAMG students, but not necessarily in the context of higher education.

Principles of Success (PoS)

Principles of Success (PoS) is an organic progressive change strategy centred upon enhancing race inclusion. It is developed by three of the named AAMG authors possessing expertise in academic programme development, teaching and learning, community development and careers and employability. The organisational cultural dynamics surrounding the inception of PoS was heavily influenced by a legacy of multiple task and finish projects within different faculties across the university. Through analysis of these projects, it became clear that there was a distinct lack of enhancing the sense of belonging, leveraging cultural wealth and the absence of a clear integrated progressive approach that aligned with the strategic priorities of the university. PoS initiated with providing solution-focussed workshops during the academic year 2018-2019, working with students as partners in order to facilitate a strategic and action-orientated means of creating sustainable change. The outcomes of these workshops informed the development of four strategic work streams; (1) Student Self, (2) Staff and Organisational Development, (3) Research and (4) Culture.

In the academic year 2019-2020, work stream (1) developed into the PoS Student Leadership Programme for AAMG students. The development of the other three work streams followed work stream (1). Work stream (1) and (2) form the structure for the self-study section of this article. The Leadership Programme attracted 150 applications from AAMG students across the university. Recruitment occurred during induction week, where the programme was promoted in several courses ranging across the faculties of the university. This process revealed the lack of racial awareness and appreciation of students’ diverse backgrounds amongst some colleagues. Seeing students alienated within a cohort with no attempt to build an inclusive environment provided more motivation towards delivering the Leadership programme.

Despite the lack of understanding and support from Senior Leadership who seemed to think that such a programme would ‘create a ghetto’, the programme was welcomed and encouraged by Heads of Departments across the university. Through deploying a forensic admission process, we accepted fifty students onto the programme. Students were accepted from first-year undergraduates up to those at postgraduate level. We accommodated a diverse mix of students considering gender, sexual orientation, disability, and cultural background. The programme consisted of ten three-hour seminars designed to leverage student cultural wealth, enabling them to be their authentic selves. We embodied an organic, students-as-partners approach which at its heart integrated an innovative relational pedagogy. The course included, but was not limited to, facilitating the following outcomes: enhancing confidence and self-leadership, enabling proactive ownership of participant career narrative, improving employability, and developing professional networks within and outside of AAMG professionals and advocates.

We have been encouraged by the students who took part in the programme, particularly with the knowledge that all final-year undergraduates achieved at least a 2.1 or 1st degree classification degree. All students who successfully completed the scheme demonstrated leadership in various capacities, such as student course representatives, student employability mentors, NHS volunteers for dementia patients, and in community development initiatives. Some of them even supported widening access work to HE initiatives to inspire and raise aspirations of local secondary students from working-class areas to further their education.

Action has been taken by AAMG staff and students, similarly to ‘the fugitive’ in Moten and Harney’s (2013) undercommons. These AAMG staff find sanctuary amongst themselves and their students where the work ‘is as necessary as it is unwelcome’ (Moten and Harney, Reference Moten and Harney2013: 101–102). However, those who do such fugitive work with genuine intentions need to examine their own practices to constantly improve and be inspired to inspire others (Milner, Reference Milner2007). It is through an ethic of love (hooks, 1995), through which PoS has been developed.

Inspired by the work of Milner (Reference Milner2007), we are taking a step back in examining our roles in the initiative and conducting a self-study. The questions informing this self-study are: (1) how have our own racialised experiences influenced the development and leadership of PoS? (2) How did student participants perceive PoS? (3) How did the Student Self workstream of PoS inform the development of a ‘Progressive Relational Pedagogy’ and (4) How does the Progressive Relational Pedagogy inform Staff and Organisational Development?

Methods

In order to address the research questions above, the methods for this study include: (1) the self-study of three staff who led and facilitated in PoS; and (2) the gathering of a half-dozen student participant views of PoS via one-to-one interviews. The self-study aspect of this research has been guided by the work of Milner (Reference Milner2007). He systematically reflected upon his own teaching practice, as a black instructor, to get the majority of his white students (in the USA context) on a teacher education module to engage with, discuss, and understand the complexities of racism. Milner’s approach to self-study is derived from narrative inquiry, particularly the work of Connelly and Clandinin (Reference Connelly and Clandinin1990). As Milner reflected (Reference Milner2007: 592):

I attempted to capture the multiple stories around race that I experienced as a way to better understand my own practice (my curriculum decisions) as well as to shed light on the multiple tensions inherent in living and experiencing racism in a multicultural society. Moreover, I attempted to help the students in my course become aware of how their own experiences shape the curriculum.

Although we adopt Milner’s self-study for this work, we were aware of our different context, an English university, and that our initiative was race-specific for the benefit of AAMG students. An account evaluating the pre-, during-, and post-delivery was provided by the self-study of the three university staff who led and delivered PoS. They are represented with one voice in the findings. Through several meetings after the completion of PoS in 2020, the three facilitators met with Manuel to reflect on evaluation of the initiative and capturing the student voice. Although they already had data such as student evaluations, the PoS facilitators were keen on creating some distance between themselves and students to capture the student voice. Manuel, who has no ties to PoS and the students, was brought into the fold to interview students who took part. In these preliminary discussions initially to discuss capturing the student voice, the three facilitators reflected upon the scheme and their delivery. The notes from these meetings, sometimes recorded over Zoom, form the basis of the presentation of the staff self-study as one voice below.

Unlike the staff self-study, the student experience of the initiative is presented as a counter-story within the critical race theory education tradition of composite character (Solórzano and Yosso, 2001; Reference Solórzano and Yosso2002; Harper, Reference Harper2009; Patton and Catching, Reference Patton and Catching2009; Hughes and Giles, Reference Hughes and Giles2010; Milner and Howard, Reference Milner and Howard2013). There are a few reasons for employing a composite character to present the student experience: (1) it places experiential knowledge and experiences of racism at the centre (Solórzano and Yosso, Reference Solórzano and Yosso2001; Milner, Reference Milner2007); (2) it ensures the anonymity of students’ experiences with the use of composite characters (Patton and Catching, Reference Patton and Catching2009); and (3) compositing is ‘helpful in bringing in similar themes that arose across narratives to present a more cogent picture of participant experiences’ inviting ‘readers into the lives of composite characters that explicate’ the pervasiveness of white supremacy in the academy (Patton and Catching, Reference Patton and Catching2009: 717).

There were fourteen students who released their names to the three facilitators of PoS for Manuel to make contact for them to be interviewed. Out of the fourteen contacted, six students replied to be interviewed. The interviews lasted from twenty minutes to an hour. The interviews were then transcribed via the dictation option on Microsoft Word. While an imperfect transcribing and less costly process, the dictation option allowed for Manuel carefully to listen to the audio and tease out themes during transcription. The analysis of the student data has informed the student composite character, Tonie, below. It is important to remind the reader that counter-stories, particularly those below, are not fictional and necessarily representative of all AAMG students. However, they are grounded in actual life experiences, derived from a variety of sources, and combined to tell the experiences of marginalised communities (Patton and Catching, Reference Patton and Catching2009: 716). Tonie’s vignette below encapsulates the student views gathered about PoS and how it was a place of belonging to reflect upon her own culture, her own values, and how this can become translated into informing her own professional development.

Findings

Reflective account of students on principles of success (work stream 1)

‘Until you know who you are yourself, you can’t lead someone’

– Tonie.The student peers at the mobile phone, there remains ten minutes left of the lecture. Tonie lets out a silent, exasperated sigh to not disturb the other students sitting on either side. Today’s a Wednesday, approaching lunchtime. Tonie is excited about meeting up with friends for lunch and before they all head off together to the next PoS session in the afternoon. Tonie has not met up with them since returning back from the Christmas holidays. PoS, for her, was a space of belonging.

The PoS session stands in contrast to the current constitution of the lecture theatre in many ways, through Tonie’s eyes. Perhaps, the biggest difference is that the majority of students and staff on the accountancy course are white. The PoS staff and guest speakers mostly hail from Caribbean and African backgrounds. The PoS initiative is aimed at all AAMG students in the university, and this was comforting. The initiative brought students and staff together in a space where certain things like knowledge of holidays and festive events from various cultures were recognised immediately. For students like Tonie, this was significant and meaningful as one can speak openly about their heritage and culture, and it resonates with someone else in the room. This contrasts with the amount of energy and labour it would take to explain these cultural subjectivities to someone on the accountancy course.

PoS did not only offer a place of comfort for students categorised as AAMG, it also offered a sense of belonging and community. Tonie would not hesitate to disclose the loneliness experienced throughout the course and university life until meeting others on PoS. Friendships emerged for Tonie on PoS while in her final year of university. It is better late than never to feel like you belong in university and gain new friends. Perhaps, experiencing PoS in the first year would have been more beneficial in transitioning into university life after arriving from school. However, the PoS did not develop to initially support students in university transitions. It emerged from the hearts of the PoS staff members to enable young AAMG students to become leaders themselves.

The building-up of leadership skills was the central reason for Tonie placing an application to be a part of the PoS programme. Tonie was aware of the programme prior to application through social networks via the student union and black student society. It was all word-of-mouth until an official announcement emerged on the university’s virtual learning environment towards the start of final year of study. Once announced, Tonie wasted no time to apply, particularly with a desire to build up professional development and, most importantly, the curriculum vitae for potential employers. After being notified of her successful application, Tonie can vividly recall entering the PoS space for the first time and being inspired and motivated by the leaders, facilitators, and guest speakers of PoS. It was empowering not only to be in the room, but also being equipped with tools and concepts not acquired on the accounting course. The concept of cultural wealth, for Tonie, was the most valuable. It made her self-aware. Not only does it challenge deficit perceptions of Tonie’s cultural heritage that are pervasive in the academy, but it offers an empowering sense of self. This is something that Tonie has reflected upon throughout the Christmas break, and would like to share with friends at lunch and with staff members leading the PoS this afternoon. She even recorded her reflections on her mobile phone on the notability app:

Until you know who you are yourself, you can’t lead someone. You can’t be a leader if you can’t even identify, and open up yourself. A lot of the PoS programme was about owning your cultural wealth. This is what I bring to the table, and it may be different from the conventional stuff. Despite maybe meeting a diversity quota or whatever, I’m not just bringing in the academic work and graduating from university. I am also bringing extra cultural experience that someone from a westernised background does not have. And as a leader, and coming from a more cultural background, you could say, I’m a bit more open and receptive to people who understand that sense of understanding and what it feels like – not to be accepted – so you have to listen more.

This feeling of being better equipped and empowered to take on life after graduating was collective. This was exemplified by all PoS students rejecting the institutional category of BME and identifying themselves as students from AAMG backgrounds. Also, Tonie has reflected on new confidence, and aspires to learn of different cultures in and outside of university. Hailing from a Caribbean and African background, Tonie felt more advantaged in contrast to other students on PoS as many of the facilitators and guest speakers shared a similar background. As students begin to close their laptops, ruffle their bags, and close their notebooks throughout the lecture theatre, Tonie is thumbing on the mobile phone a question to take to her newfound friends and staff on PoS: ‘How expansive and inclusive can PoS be for our future AAMG students?’

Self-study of PoS delivery team

Due to limited space, the self-study will provide a condensed narrative through the guise of how PoS developed. It will be presented through the ‘Student Self’ and ‘Staff and Organisational Development’ strategic workstreams.

The reader might be thinking this is an emotive reflection and has no place in a social science body of thinking; we reject this stance because it represents the ‘normalisation’ of academic thinking that has led to a plethora of interventions that have not disrupted the systematic racial inequalities in HE. Papers on tackling under-representation, increasing diversity targeting (Moody and Thomas, Reference Moody and Thomas2020), rig-fencing whoops I meant ring-fencing, widening participation, reductive leadership programmes (which are more akin to ‘let’s teach you to fit in’), widening access, unconscious and or conscious bias training, let’s talk about race, the student voice, equal merit, Race Equality Chartermark, value-added and not forgetting targeted recruitment and outreach directly related to ‘protected characteristics (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, O’Mahony, Khan, Ghaffar and Stiel2019), all contribute to this process of normalisation.

Self-study work stream 1 – student self

In this section of the article, the PoS Delivery team share their reflections on the delivery of the programme, based on their collective experience of thirty-five years of working and navigating within Higher Education. Through the delivery of the programme, it was inspirational to observe how students grew in confidence. Here we are seeking to articulate why the programme was so impactful in its delivery. To aid the understanding of our self-study surrounding the Student Self workstream, we have created relevant themes that together contribute towards the narrative.

Cultural wealth and principles of leadership seminars

Based on our collective experience of working in Higher Education, we felt it was of vital importance to provide students with a sense of belonging. We facilitated this in two ways. First, at the beginning of session one, we welcomed students in their native languages to reflect their value and celebrate the diverse backgrounds of the cohort. Secondly, as part of the initial application which students had to complete to be considered for the programme, students were able freely to articulate their ethnicity rather than having to subscribe to predefined categories. The organic descriptor of African, Asian and Other Minoritised Groups (AAMG) emerged from this, reflecting the wider zeitgeist around descriptions of ethnicity which is resulting in an increasing repudiation of the term BME (Fakim and McCauley, Reference Fakim and McCauley2020).

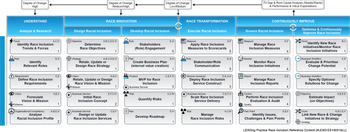

We utilised Yosso’s cultural wealth model (Yosso, Reference Yosso2005) to enable students to identify and leverage the cultural wealth innate to them and their cultural backgrounds. In so doing we rejected the negative preconceptions inherent in the ‘deficit thinking’ which we had encountered in relation to AAMG staff and students. The concept of cultural wealth was reinforced throughout the programme, as illustrated in Figure 1. The greyed-out boxes represent how each session reinforced different aspects of Yosso’s cultural wealth.

Figure 1. PoS student self aligned with Yosso’s (Reference Yosso2005) cultural capital model.

How the PoS leadership programme develops the cultural wealth of AAMG participants

By sharing our personal and career journeys with the cultural wealth we had developed along the way, this enabled students to recognise their own cultural capital.

As part of our teaching on what is required to be an authentic leader, we introduced students to the concept of the Golden Circle developed by Sinek (Reference Sinek2009) which focuses on how leaders can inspire cooperation, trust and change by communicating their ’why’ and their purpose. We referred to habits one and two from the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (Covey, Reference Covey2004) emphasising beginning with the end in mind. Helmstetter’s (Reference Helmstetter1990) concept of self-talk was integrated with developing your ‘super-strengths’ (Mindflick, 2018) forming a key part of their leadership proposition. It became evident to us that students recognised the importance of taking control of their subconscious mind along with developing self-talk statements to support a positive re-programming of their mindset.

Self-image and career narrative seminars

Guest speakers from AAMG supported these seminars by outlining their career journeys and the success principles leveraged to enable their authentic selves and navigate successfully in their field. As part of these sessions, we introduced students to the notion of a ‘career narrative’, partly based on the Careers Construction theory developed by Savickas (Reference Savickas2005). Reference was made to Coleman’s (Reference Coleman1996) concept of Performance, Image and Exposure (P.I.E.) in relation to successful career progressions as part of the rationale for students controlling their career narratives.

Different philosophical perspectives on leadership were explored (April and Ephraim, Reference April and Ephraim2006) as was Hall’s (Reference Hall1976) theory of low and high context cultures. This facilitated understanding on how culture impacts communication and engagement. The importance of being authentic was emphasised. Students were given the opportunity to consider their cultural wealth, e.g. faith and engagement in leadership project opportunities, facilitated by the programme.

We regarded this session as a turning point for the students. Owning their career narrative was a fundamental prerequisite to enabling them to develop and execute authentic leadership that leveraged their cultural wealth. Furthermore, the students recognised that their cultural wealth was integral to their leadership signature. It was clear to us that an emphasis on ’valuing’ disrupts the shackles of normative legacy, rather than intervention, additional support or additional provision. In short, it’s purely how much you are willing to invest in your students’ ‘success’, it’s about having ethical ambition (Bell, Reference Bell2002), the acceptance that the complexity of equity does not sit with the individual but firmly within the human structures of power. Once you acknowledge this as a teacher/lecturer/facilitator it’s like ‘droppin science’ (Perkins, Reference Perkins1996).

Action planning, professional networking and career opportunity seminars

To augment the work on adopting a more positive mindset and reprogramming their self-talk, students were introduced to concepts such as Covey’s (Reference Covey2004) Circle of Influence and Circle of Concern. This encouraged them to move from a reactive to a proactive focus on problems and challenges. There was an emphasis on how to develop SMART action plans and manage critical relationships through Stakeholder Mapping (adapted from Mendelow, Reference Mendelow1991). Students were asked to consider their ‘elevator pitch’ and shown how LinkedIn could be a useful platform both to present themselves professionally online and to develop professional networks. They also participated in a speed networking event with AAMG professionals drawn from a diverse range of backgrounds including: Higher Education; Community Development; Learning Mentorship; Social Entrepreneurship; Social Care and Global Wealth Development. Career development models were taught and aligned with the University’s employability award.

To enable students to understand that there are various career pathways which they can pursue without jeopardising their authentic self, we facilitated an employer networking event. This featured a range of organisations that value diversity and seek to leverage the cultural wealth of their workforce. The organisations that participated represented the public, private and charitable sectors and many were signatories to the Business in the Community (BITC) Race at Work Charter (2020). It was clear to us that the students were empowered by the sheer range of AAMG professionals they had connected with during the seminars and felt inspired and motivated to take ownership of their future.

Leadership signature presentations

As a prerequisite to graduating from the PoS Leadership programme, students were required to deliver a seven minute presentation in front of an audience of AAMG professionals and advocates. The aim of the presentation was to enable students to articulate their leadership signature, outline their cultural capital, identify which success principles were most relevant to them, how they applied it; and outline how they planned to consolidate on their leadership learning over the next six months (in their academic endeavours and career development). In studying the Leadership seminars, we realised that our marketing campaign, teaching environment and pedagogical approach had already contributed towards creating a safe space which enhanced the students’ sense of belonging.

As practitioners it is pivotal for us to impart the learning which we gained from this experience. Prominent in our reflections were:

-

‘By us, for us’ – it was vital that the programme was facilitated by AAMG staff who were authentic in terms of leveraging their cultural wealth and honest and frank about the realities of career navigation within and outside of Higher Education. This influenced the criteria used to select AAMG speakers. The reality is that not everyone from an AAMG background is comfortable in their own skin and willing to represent by sticking their head above the parapet. Some may collude with the status-quo which has ill-served AAMG students and staff all in the name of safety, security and career progression.

-

The creation of a safe space that students don’t experience on a day-to-day basis – the opportunity to share experiences as AAMG students and staff within Higher Education was affirmational and therapeutic in terms of generating progressive and proactive strategies.

-

Being comfortable with who you are regardless of cultural or religious affiliations: for example, positioning religious faith as a cultural asset to be leveraged as part of an authentic leadership identity.

-

Students experiencing what majorities feel like and how privileged they felt: for example, not being judged based on your ethnic and cultural background.

The Progressive Relational Pedagogy (PRP)

Inspired by the work of Ladson-Billings (Reference Ladson-Billings1994) and Paris and Alim (Reference Paris and Alim2014), we sought to build upon the pedagogical tradition of sustaining our students’ culture and heritages in delivering our leadership programme. We combined this with analysis of seminar evaluation data and personal and student reflections for each seminar, to enable us to identify how we could appropriate a relevant relational pedagogy for HE. This drove the creation of a Progressive Relational Pedagogy underpinned by: (1) Sense of Belonging, (2) Student Voice, Value and Cultural Wealth, (3) Globalised Curriculum, and (4) Links to Industry and Community. Through embedding such progressive tenets, students were able to be their authentic selves. Progressing this practice contrasted with teachers who just cross metaphorical boundaries of racial and ethnic differences, to enable student learning and academic achievement within HE.

Self-study work stream 2 – staff and organisational development

The intention behind this work stream was to inform the development of staff and the organisation based on the findings and our self study arising from delivering the leadership programme. The four tenets of PRP provided the foundation for PoS to integrate progressive developments in Academic, Professional Services and Student Support Directorates.

From a teaching and learning perspective, this started at a module level wherein Module Leaders across an academic department were supported in evaluating their modules through a PRP lens during designated staff development. This enabled the ability to review course diets in order to identify areas of good practice alongside areas for development and enhancement such as culturally-relevant case studies and facilitating students to afford their cultural wealth into the curriculum and throughout their learning. Initially, the concept of this development was challenged by Subject Group Leaders who seemed not to understand how relational pedagogy could be integrated into a technical subject discipline. However, the most technical subject group proved to be the most progressive during the development, inspiring other subject groups with their short-term solutions on enhancing inclusivity through a PRP lens across their course diets.

From a professional and student services perspective, this supported a tailored review within eleven Functional Teams ranging across Academic and Strategic Employability, Business Operations and Business Engagement Units. Service managers were able to identify gaps in their provision as well as sustainable service improvements with some initial performance indicators. Functional Teams were awakened to the fact they had not considered their services through a PRP lens and that this progressive thinking enabled new ideas and concepts that could enhance the inclusivity of their provision. This included creating clear objectives strategically supporting race inclusion, and reviewing service artefacts (e.g. policies, procedures, practices etc) through the lens of race to ensure a racially-inclusive approach to process execution.

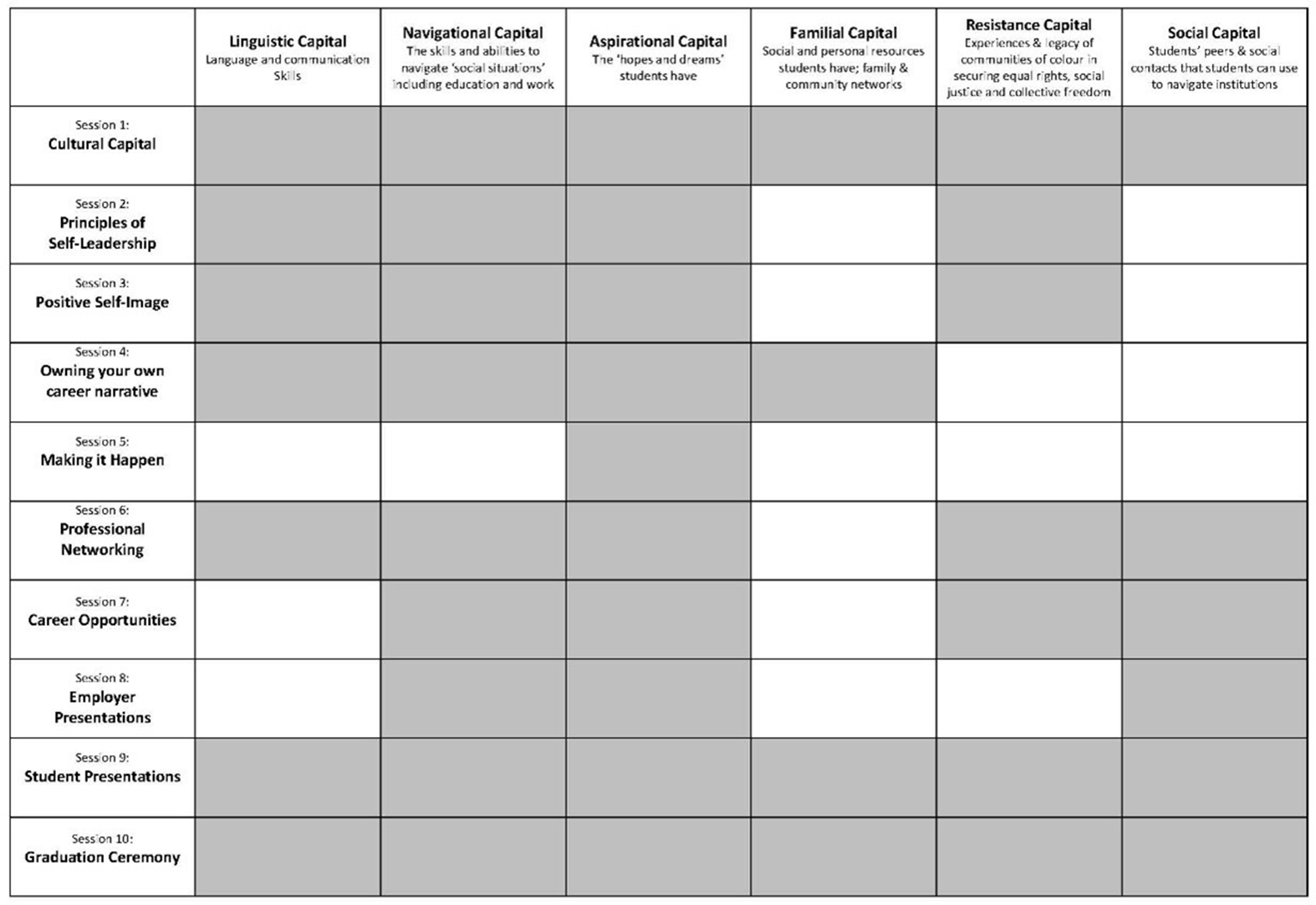

As part of the ‘Architectural Intentions’ presented by the three PoS facilitators (Caine et al., Reference Caine, Gilroy and Greaves2019b), the developments with these respected university directorates provided the opportunity for our self-study to identify the opportunity to exercise interdisciplinary practice by integrating works from domain ontology within an informatics context. Ontology enables us to share and reuse meaning (Gruber, Reference Gruber1995). It facilitates the definition of concepts and relationships that are essential when attempting to model a domain. Gruber is known to have established ontology within the informatics and computing domain, whilst the routes of ontology lay firmly within social science, based on a philosophical premise; ‘the nature of being or reality’ (Denzin and Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln2011). Borst and Borst (Reference Borst and Borst1997: 12) effectively describes ontology, implying how this can relate to domains outside of social science, suggesting Ontology is a ‘formal specification of a shared conceptualisation.’

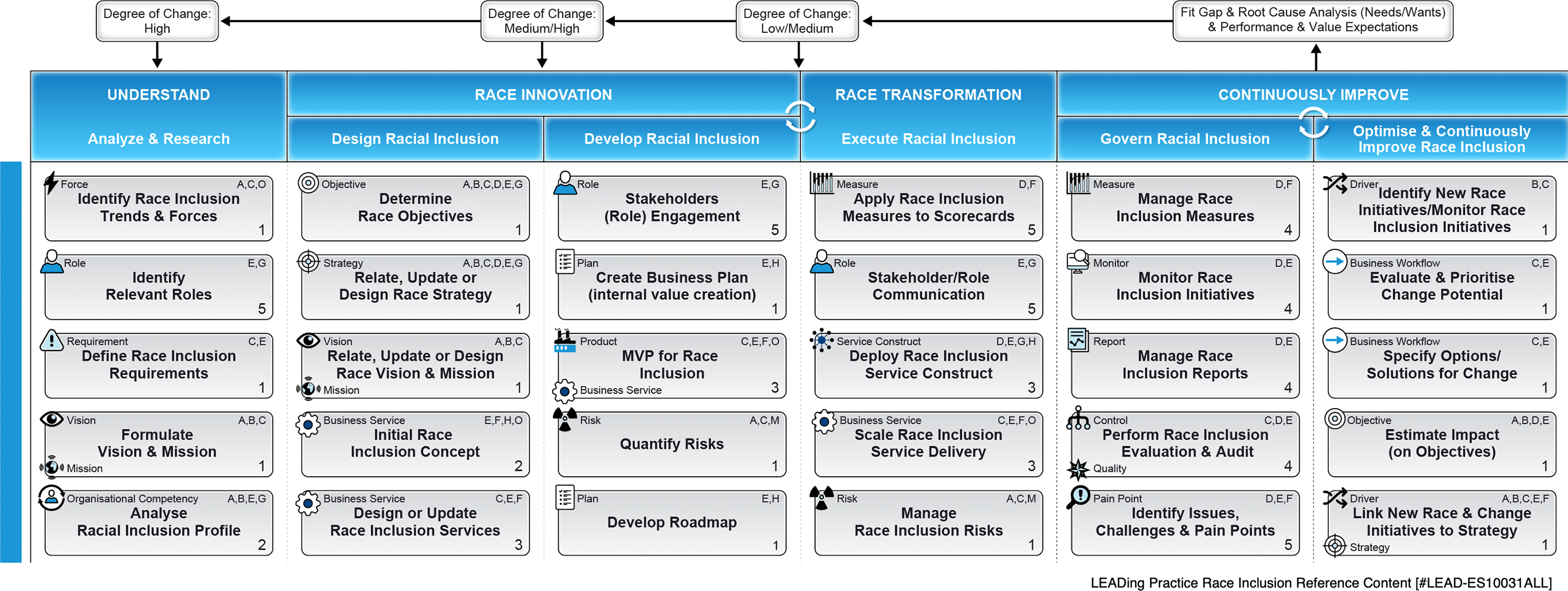

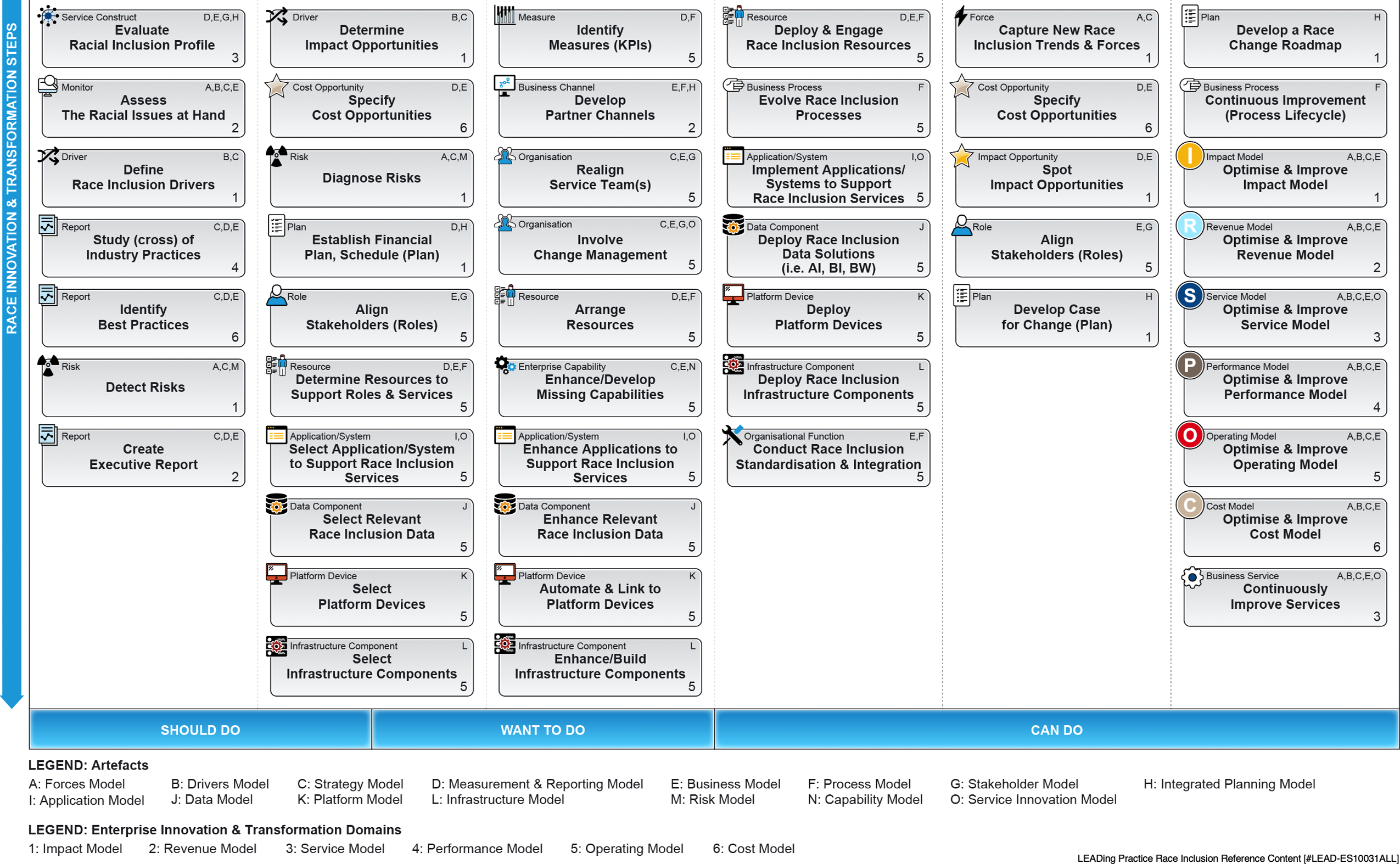

Like other domains such as Strategy (Caine and von Rosing, Reference Caine and von Rosing2020) and Business Process Management (von Rosing et al., Reference von Rosing, Urquhart and Zachman2015), Race Inclusion can also benefit from ontology and a structure that seeks to formalise and facilitate a consistent way of sharing meaning within a race context. We used the LEAD Enterprise Ontology (LEO) (von Rosing and Laurier, Reference von Rosing and Laurier2015; Caine and von Rosing, Reference Caine and von Rosing2018) as a basis for developing this structure.

LEO has evidently been used to underpin the development of Enterprise Standards that support the alignment and integration between strategy, processes, services, governance, and systems (von Rosing et al., Reference von Rosing, Urquhart and Zachman2015; von Rosing et al., Reference von Rosing, Fullington and Walker2016; Bach et al., Reference Bach, von Rosing and von Scheel2017; von Rosing et al., Reference von Rosing, Okpurughre and Grube2017;). It provides the foundation on which the Race Inclusion Framework is built. LEO is a collection of ontologies categorised and classified, providing a structure to share meaning across different domains (von Rosing and Laurier, Reference von Rosing and Laurier2015). This provides the basis for creating new ontologies that can benefit from existing ontologies where applicable (as demonstrated with Race Inclusion Ontology). Figure 2 visualises where LEO is adapted to support the development of the Race Inclusion Framework. The areas highlighted in red are the ontologies that the Race Inclusion Framework is built upon.

Figure 2. LEAD Enterprise ontology highlighting relevant ontologies for the race inclusion framework (von Rosing and Laurier, Reference von Rosing and Laurier2015; Caine and von Rosing, Reference Caine and von Rosing2018).

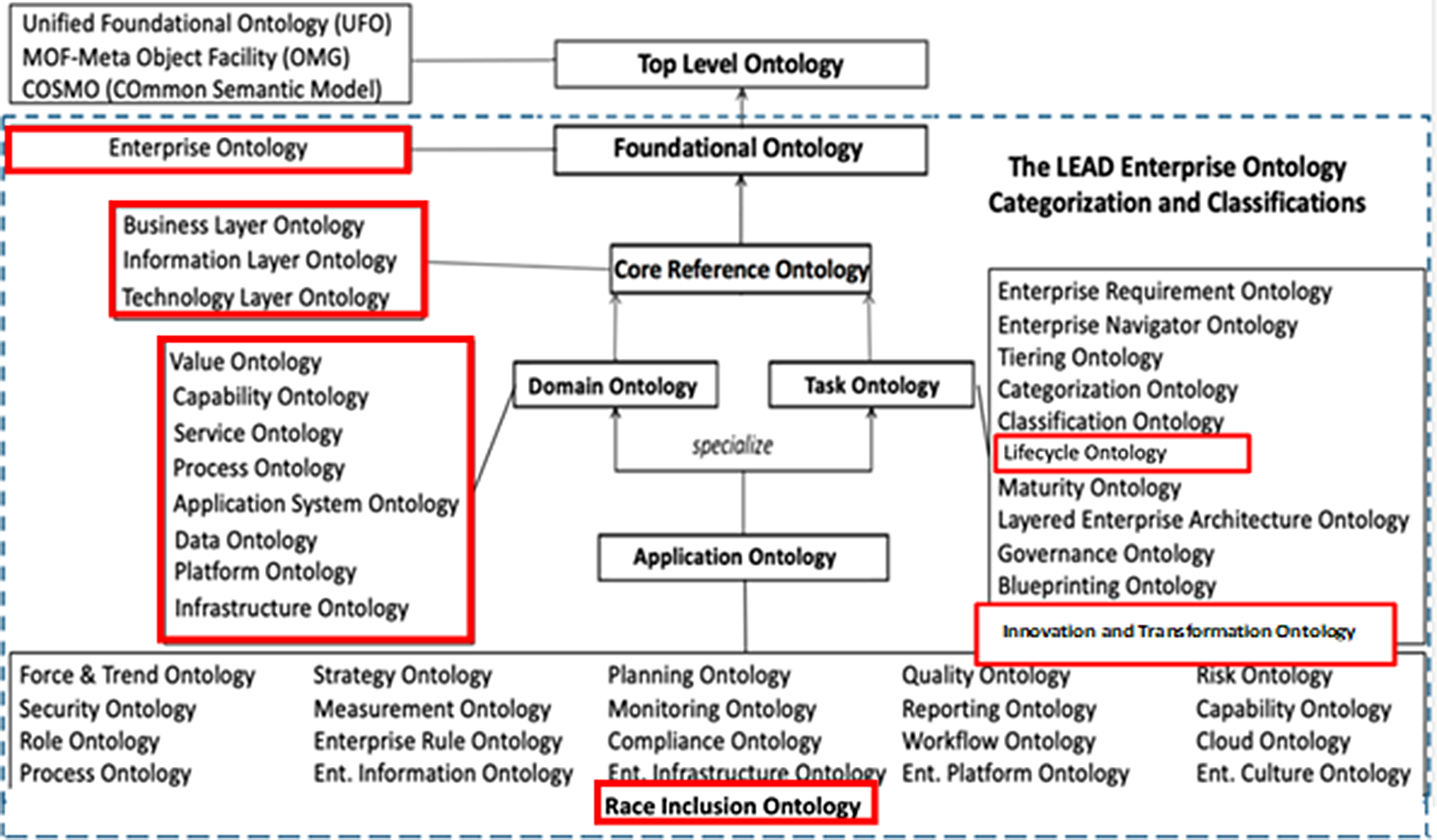

The Race Inclusion Framework is an iterative process in which we seek to understand the race inclusion issues, challenges, assumptions as well as the stakeholder requirements and needs. By defining the issues at hand with the desired state, we identify alternative race inclusion ideas, concepts, strategies and solutions that might not instantly be apparent with the traditional way of thinking and working. The Framework provides an agile and systemic-based approach to solve the challenges at hand whilst remaining industry and sector neutral. The Staff and Organisational Development work stream is now underpinned with methods taken from the Race Inclusion Framework. The Framework facilitates the ability to translate race strategic priorities into operation, whilst deploying appropriate mechanisms to monitor, manage and continuously improve performance. This supports the ability to attain sustainable transformation (see examples in Bach et al., Reference Bach, von Rosing and von Scheel2017; von Rosing et al., Reference von Rosing, Okpurughre and Grube2017).

The Framework consists of phases that are inter-linked, together forming a lifecycle that builds upon the Lifecycle Ontology from the LEO. The four high-level phases include Understand, Race Innovation, Race Transformation and Continuously Improve (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Race inclusion framework phases.

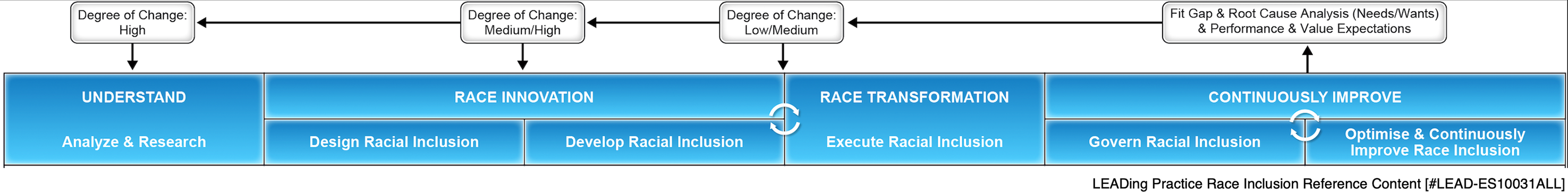

Each phase includes practical steps that can be tailored towards a particular organisational context. Artefacts related to each step provide specific views and models that connect to a specific domain that supports innovation and transformation. The models Impact, Revenue and Service relate to Innovation; whilst Performance, Operating and Cost relate to Transformation (see Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Race inclusion framework steps.

Figure 5. Race inclusion steps with artefacts, innovation and transformation domains.

Conclusion

PoS is evidently an organic and innovative approach that provides a race inclusion action-orientated means of working towards sustainable transformation within HEIs. The Progressive Relational Pedagogy – underpinned by (1) Sense of Belonging, (2) Voice, Value and Cultural Wealth, (3) Globalised Curriculum and (4) Employability Links to Industry and Community – provides a foundation for evaluating and enhancing core practice across Academic and Professional Services and Student Support Directorates. The Race Inclusion Framework provides the ability to integrate the Progressive Relational Pedagogy into an overarching framework that facilitates alignment, integration and governance across an organisation’s operational, tactical and strategic tier. The framework has supported PoS in progressing transformational change within a HEI.