I IntroductionFootnote 1

Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. In 2018, the country had one of the lowest land to man ratios in the world, which was estimated to be 0.08 hectares per person (World Bank, 2020b). While in recent years, the share of agricultural land in total land has been around 70% (World Bank, 2020b), there is a growing demand for land for non-agricultural activities, especially to establish new homes, roads, educational institutions, and industries. This puts immense pressure on land availability and land prices, and thus, land is now the scarcest factor of production in Bangladesh.Footnote 2

The scarcity of land and resulting high prices have important implications for the prospect of industrialisation of the country. The situation is yet more complicated due to the weak land management system, which perpetuates land-grabbing, high rent generation, and ineffective property rights. These, in turn, constrain investment opportunities, both from home and abroad. The inadequacy of land is often identified as one of the reasons for the low level of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Bangladesh.Footnote 3

The scarcity of land and consequent high prices exacerbate the challenges related to the dysfunctional land administration and management system in Bangladesh (Hossain, Reference Hossain2017). The land administration and management system in Bangladesh is age-old, inefficient, and involves a considerable degree of inefficient and corrupt practices. Also, the land transfer process is jeopardised by inadequate and flawed land records, and thus, the system fails to keep pace with the growing demand and changing landscape of the economy. Efficient land management has important implications for various development goals, such as food security and ensuring a favourable business environment for private investment, and thus undertaking necessary reform to develop a consistent and functional land administration and management system in Bangladesh will be crucial in the coming years.

All of this justifies government intervention in the land management system. The land issue is discussed extensively in the country’s Seventh Five-Year Plan, 2016–2020. The plan identifies many factors as constraints on the functioning of effective land management and administration in Bangladesh: antiquated records, complex and ineffective policies, high transaction costs, and a weak taxation policy. Hence, the plan stresses a range of institutional reforms: digitisation of records, and simplification of transactions and land registration. Additionally, the plan underscores the special economic zones (SEZs) initiative as a medium for providing access to serviced land to investors from home and abroad. However, there are many difficulties regarding land acquisition under the SEZs initiative, as such initiatives rely heavily on the existing dysfunctional land system. Without effective institutional reforms in the land administration and management system, the SEZs initiative is unlikely to realise its full potential.

Against this backdrop, this chapter analyses the importance of a well-functioning land management and administration in Bangladesh; explores the history of the policy reforms and the evolution of rules and regulations related to land administrative and management in Bangladesh; analyses institutional complexities in the current system of land management; explores how the SEZs initiative has emerged as an alternative management system and the complexities related to the acquisition of land for SEZs; and, finally, suggests areas of improvements related to land administration and management. This chapter draws on available data, interviews conducted with key informants, focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted with relevant stakeholders, and the use of relevant analytical tools to understand the institutional challenges in the land management and administration system in Bangladesh.

II Consequences of Land Scarcity and Inefficient Land Management

In recent decades, with a highly dense population, South Asian countries have been experiencing an accelerated rate of land fragmentation. Most of these countries depend on the agriculture sector for a major share of employment. Hence, land fragmentation has forced some farmers to become landless or land-poor and to lean on sharecropping or to take on agricultural day-labour as an occupation. The law of inheritance, lack of a progressive property tax, heterogeneous land quality, and an underdeveloped land market perpetuate the problems in the region (Niroula and Thapa, Reference Niroula and Thapa2005; Siddiqui, Reference Siddiqui1997). Greenland et al. (Reference Greenland, Gregory, Nye and Barbier1997) also argued that insecure land tenure alters the decision-making process of production in favour of short-term time horizons, which has a detrimental impact on investment decisions.

Like most other South Asian countries, Bangladesh faces many of the land-related institutional challenges mentioned above. Fragmentation of land in Bangladesh perpetuates inefficiency and hurts overall production in the agricultural sector (Rahman and Rahman, Reference Rahman and Rahman2009). The gravity of the fragmentation of landholding in Bangladesh is that small landholdings (less than 2.5 acres) occupy more than 84% of the total area of farm holding in Bangladesh. It is also found that functional landlessFootnote 4 households (households in which own no more than 0.5 acres of land) account for more than one-fourth of farming households in Bangladesh.

Fragmentation of landholding also has important implications for private sector investment in non-agricultural activities. Industries require large amounts of land, which is rarely available from a single owner, due to the highly fragmented ownership nature. Therefore, potential investors have to secure land from multiple owners of adjacent land who are will to sell. However, where owners are unwilling to sell, there are cases when the buyers, with the help of politically powerful groups, force them to do so.Footnote 5 This is a common practice among powerful business elites and poses a serious problem to those investors who lack ‘effective’ connections with powerful political groups.

Rapid urbanisation is a growing phenomenon in Bangladesh. Over the past four decades, the urban population in Bangladesh increased at a rate faster than the South Asian average. The share of the urban population in the total population in Bangladesh in 1980 was only around 15% (the South Asian average in 1980 was 22.3%), which increased to 36.6% in 2018 (the South Asian average in 2018 was 34%) (United Nations, 2019a). Bangladesh is fast losing arable land due to growing industrialisation and rapid encroachment of human habitats on farming areas (Khan, Reference Khan2019). A consequence of the depletion of farmland is the growing migration of landless people from rural areas to the urban areas, landing mostly in urban slums. Also, as private investors intensify exploration of the availability of land in remote areas of the countryside to set up factories, this leads to a hike in the price of agricultural land (Hossain, Reference Hossain2017).

Apart from land scarcity, administrative complexities and associated institutional challenges also appear to be acute in Bangladesh. The existing policies are inconsistent due to the outdated and complex land laws. The laws are described in such a way that they are hard to implement. Raihan et al. (Reference Raihan, Fatehin and Haque2009) argued that though various reform efforts were undertaken related to land management and administration, in many cases they were not effectively implemented. The way in which land is currently administered remains firmly rooted in practices established during the colonial era: little has changed in the post-independence era.

Raihan et al. (Reference Raihan, Fatehin and Haque2009) also highlighted that though the Pakistan and Bangladesh periods saw attempts at redistributive reforms through the establishment of land ceilings and placing land in the hands of the tiller, and returning water bodies to those who fish them, the reforms were largely circumvented by the wealthy and powerful. This was particularly true in the case of the distribution of khasFootnote 6 land among poor people. The estimated amount of total identified khas land in Bangladesh is 3.3 million acres, with 0.8 million acres of agricultural khas land, 1.7 million acres of non-agricultural khas land, and 0.8 million acres of khas waterbodies. The above-stated amount of khas suffers from underestimation (Barkat et al., Reference Barkat, Zaman and Raihan2001). A large part of the khas lands are grabbed by local elites and powerful forces who have a strong political nexus (Rahman, Reference Rahman2017).

Hossain (Reference Hossain, Hassan, Rahman, Ali and Islam2017) emphasised that corruption, administrative problems, and ancient practices of data management are the common features of the land management system in Bangladesh. Hasan (Reference Hasan2017) also labelled the land administration system in Bangladesh corrupt, inefficient, and unreliable, and emphasised that the problems of land management are acute due to the overlapping involvement of multiple government bodies in the land management system. The basic functions of land administration (record-keeping, registration, and settlement) are maintained in different offices under different ministries, and there is a lack of coordination among these organisations. Hence, the system enables multiple ownership, leads to duplicate records, creates disputes, and exacerbates land-related corruption.

There are also several institutional challenges related to land acquisition in Bangladesh. According to Atahar (Reference Atahar2013) and MJF (2015), the process of determining and implementing compensation for acquired land is arbitrarily determined and lacks transparency. Unequal land valuation, unfair compensation, and corruption are all elements of the acquisition process. The amount of monetary compensation that an individual receives is often less than the land’s actual market value. Moreover, the valuation method is not widely credited. Government officials have the monopoly power to decide location, area, and compensation rates, without consulting the owners. Using loopholes in the law, government officials determine compensation that is below the market price. In some cases, some individuals obtain a higher value by means of bribery and nepotism. According to a survey conducted by MJF, Uttaran and CARE Bangladesh, 69.5% of studied households reportedly lost land in the last 10 years, among which one-third reportedly lost land due to land-grabbing (18.9%) and acquisition (13.2%) (MJF, 2015).

Inefficient land management is not specific to Bangladesh. There are problems in all South Asian countries, as can be judged from a quick review of the literature. Wijenayake (Reference Wijenayake2015) discussed land administration in Sri Lanka, which was found to be fragmented and geographically incomplete. Due to complications and fear of failure, the Sri Lankan Government had neglected the parcel-based land information system (where parcel refers to a standard of measurement of land used in the land information system). Perera (Reference Perera2010) argued that Sri Lanka’s land registration system should enforce pragmatic strategies rather than relying only on standardised and costly approaches. Similarly, Ali and Ahmad (Reference Ali and Ahmad2016) argued that due to a diverse range of issues, ranging from economic and social, to technical, legal, political and institutional, land administration in Pakistan has huge problems. Non-conducive policies, complex legal framework, unnecessarily restrictive regulations, weak legislation, distinct administrative bodies, differential access to information, lack of standardised data and ICT infrastructure, weak coordination, etc. are barriers to efficient land administration in Pakistan and several policy reforms are needed to enhance the capacity of the institutions involved. Deininger (Reference Deininger2008) argued that land administration in India was complex and varied considerably across states at the time (2008). The integrated system, that tried to separate out different administrative bodies (e.g. registry and records or survey etc.), was not helping. Under the existing laws, the transfer of land was maintained by both the revenue department and the stamps and registration department, which increased transaction costs and created the potential for fraud. As rural areas became increasingly urbanised, the survey department’s responsibilities in relation to maintaining accurate spatial records of land ownership were often not fulfilled. This resulted in outdated map products of inferior quality, and land-related conflict. Thus, entrusting one single agency with sufficient capacity to maintain spatial records in rural and urban areas was deemed by the authors to be beneficial. Ghatak and Mookherjee (Reference Ghatak and Mookherjee2013) also studied land acquisition and compensation for industrialisation in India. The study found that compensation rules affected the decision-making process of the landowners and tenants. Depending on the amount received, they decided whether to sell to the industrial developers or to invest in specific agricultural activities. Moreover, the process of determining and implementing compensations was arbitrary and lacked transparency. A study by Ghatak et al. (Reference Ghatak, Mitra, Mookherjee and Nath2012) in 12 villages in Singur, India, showed that the majority of the people affected by land acquisition were marginal farmers and that an inability to distinguish between land qualities led to under-compensation.

III Overview of the Land Laws and Policies in Bangladesh

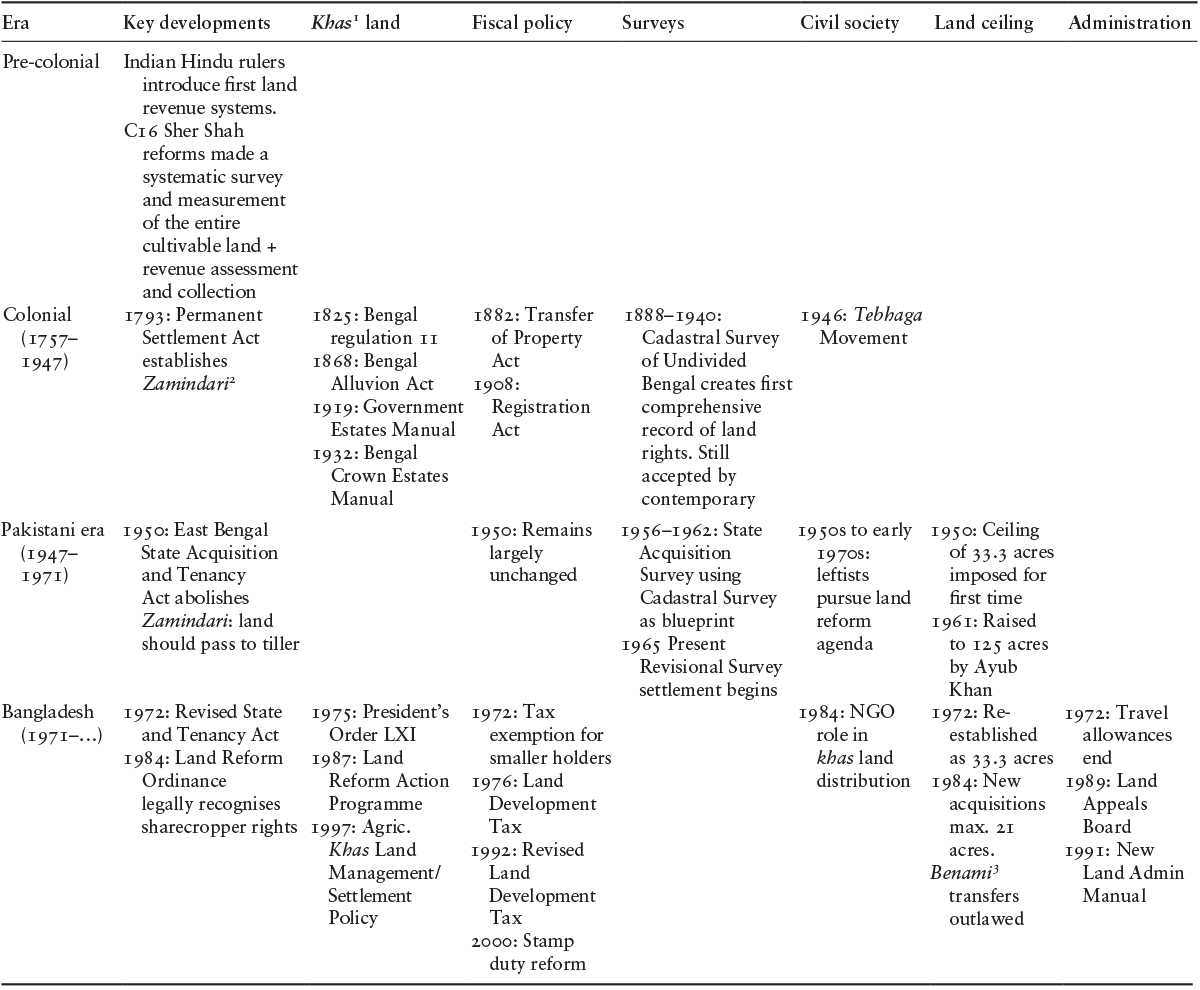

Most South Asian countries share similar kinds of problems regarding land administration and laws, due to the shared history of colonialism. For centuries, this geographical region was ruled by Arya, Hindu, and Muslim rulers who implemented a traditional revenue collection and land management system. Then colonialism provided the country with a predetermined land administration system. The land laws that were enforced by the representatives of a foreign nation had rent-seeking motives from the beginning. Therefore, the laws were seldom written with the marginal population in mind, were unnecessarily complex, and were overlapping. A land ceiling to curtail inequality based on land was imposed for the first time in 1950, after the colonial period ended. The 1950s was a notable decade for land rights in the region because of the Tenancy Act, which ensured the rights of sharecropper following the Tebhaga MovementFootnote 7 of 1946. However, the 1984 Ordinance Act placed a 21-acre celling on the acquisition or holding of agricultural land and invalidated benami transactionsFootnote 8 so that the land ceiling could be avoided. Table 8.1 shows the key developments in land policy and administration in Bangladesh from the pre-colonial period to the present day.

Table 8.1 Key developments in land policy and administration in Bangladesh

| Era | Key developments | KhasFootnote 1 land | Fiscal policy | Surveys | Civil society | Land ceiling | Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-colonial | Indian Hindu rulers introduce first land revenue systems. C16 Sher Shah reforms made a systematic survey and measurement of the entire cultivable land + revenue assessment and collection | ||||||

| Colonial (1757–1947) | 1793: Permanent Settlement Act establishes ZamindariFootnote 2 | 1825: Bengal regulation 11 1868: Bengal Alluvion Act 1919: Government Estates Manual 1932: Bengal Crown Estates Manual | 1882: Transfer of Property Act 1908: Registration Act | 1888–1940: Cadastral Survey of Undivided Bengal creates first comprehensive record of land rights. Still accepted by contemporary courts | 1946: Tebhaga Movement | ||

| Pakistani era (1947–1971) | 1950: East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act abolishes Zamindari: land should pass to tiller | 1950: Remains largely unchanged | 1956–1962: State Acquisition Survey using Cadastral Survey as blueprint 1965 Present Revisional Survey settlement begins | 1950s to early 1970s: leftists pursue land reform agenda | 1950: Ceiling of 33.3 acres imposed for first time 1961: Raised to 125 acres by Ayub Khan | ||

| Bangladesh (1971–…) | 1972: Revised State and Tenancy Act 1984: Land Reform Ordinance legally recognises sharecropper rights | 1975: President’s Order LXI 1987: Land Reform Action Programme 1997: Agric. Khas Land Management/Settlement Policy | 1972: Tax exemption for smaller holders 1976: Land Development Tax 1992: Revised Land Development Tax 2000: Stamp duty reform | 1984: NGO role in khas land distribution | 1972: Re-established as 33.3 acres 1984: New acquisitions max. 21 acres. BenamiFootnote 3 transfers outlawed | 1972: Travel allowances end 1989: Land Appeals Board 1991: New Land Admin Manual |

1 Ibid.

2 A Zamindar in the Indian subcontinent was a feudatory under a monarch with aristocratic prerogatives and hereditary titles. The term means land owner. Typically hereditary, zamindars held enormous tracts of land and had control over their peasants, from whom they reserved the right to collect tax on behalf of imperial courts or for military purposes.

3 Ibid.

After the Independence of Bangladesh in 1971, under several political regimes, attempts were made to reform the land administration, though most of them were not properly implemented. Some of these significant initiatives are described in Box 8.1, which provides a detailed timeline of land policy and administration reforms in Bangladesh. Bangladesh has suffered from archaic colonial law and administration. Although the country has undergone some forms of land reform, efforts have been rather slow-paced and uncoordinated. One example was the re-establishment of the land ceiling in 1972, retracting Ayub Khan’sFootnote 9 extension of the ceiling to 125 acres in favour of rich and influential elites. Although the ordinance and presidential orders of 1972 attempted to redistribute khas land, more specified laws regarding khas land were introduced in 1997. The ordinance of 1984 outlawed benami transfersFootnote 10 and introduced a number of reforms related to sharecropping. However, a survey conducted in 1991 showed that 90% of the rural population were unaware of the 1984 reforms (Hossain, Reference Hossain2017). A Land Administration Manual promulgated in 1991 laid down detailed instructions regarding the inspection and supervision of unionFootnote 11 and thanaFootnote 12 land offices. This manual is still in use.

Box 8.1 Land policy and administration timeline of Bangladesh

1972: A land ceiling of 33.3 acres was re-establishedFootnote 1 and various presidential orders provided for the distribution of khas land among the landless. It was expected that 2.5 million acres of excess land would be released, but in reality, there was far less. Newly formed land vested in government became a second type of khas. Exemption from land tax granted for families owning less than 8.33 acres.

1976: A variety of land-related charges were consolidated into the Land Development Tax, which covered the whole country except Chattogram Hill Tracts (CHT),Footnote 2 but deficiencies in the record system mean individual holdings cannot be checked, and switches to more heavily taxed non-agricultural uses frequently go unrecorded.

1982: The Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Ordinance, 1982.

1984: The Land Reform Ordinance 1984 limited future land acquisitions to 21 acres while retaining the existing ceilings. Benami (ceiling-avoiding) transfers to family members were outlawed, but evasion was easy. Legal recognition of the rights of share-coppers was given for the first time and sharecropping was established as the only admissible form of tenancy contract.

1988: The cluster village programme resettled landless people on state land, but only 800 villages, with some 32,000 households, had been formed by 1996.

1989: Muyeed CommitteeFootnote 3 recommended that the functions of land registration (Sub-Registrar) and record (tahsil) be brought together in a single office at field level, but this was ignored.

1989: Board of Land Administration split into Land Appeals Board and Land Reforms Board to deal with the ever-increasing volume of quasi-judicial appeals.

1991: A Land Administration Manual was created for the inspection and supervision of Union and Thana land offices.

1992: Farms of 8.33–10 acres were charged at Bangladeshi Taka (BDT) 0.5 per acre, and larger holdings at BDT 2 per acre.

1997: New Agricultural Khas Land Management and Settlement Policy introduced.

1998: Total khas land was found to be 0.75 million acres (or 3% of arable land area), but the actual amount remained unclear as a result of de facto private control arising from informal local settlements.

2001: National Land Use Policy, 2001: stopping the high conversion rate of agricultural land to non-agricultural purposes; utilising agro-ecological zones to determine maximum land use efficiency; adopting measures to discourage the conversion of agricultural land for urban or development purposes; and improving the environmental sustainability of land use practices.

2010: National Economic Zone Act, 2010: Under this act, the Government may establish economic zones. The aim is to encourage rapid economic development in potential areas (including backward and underdeveloped regions of the country) through an increase in and diversification of industry, employment, production, and exports, as well as to fulfil the social and economic commitments of the state.

2017: Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Act 2017.

The Government of Bangladesh has formulated various policies on land use, transfer, acquisition, and rehabilitation. Notable among them is the National Land Use Policy, which was adopted by the Government in 2001, setting guidelines for land use, land improvement, and zoning regulations. The policy was issued by the Ministry of Land, but its implementation faced difficulties as the land administration system is dependent on many ministries. Furthermore, other cross-sectoral policies were not harmonised in the policy, which also created problems in regard to its successful implementation. Though land acquisition by the Government is a regular phenomenon, detailed measures related to the compensation of the affected persons only came in the Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Act 2017. While many policies and reform measures have been undertaken in Bangladesh since Independence in 1971, these measures have often been ineffective due to a lack of proper implementation.

IV Challenges in Land Administration and Management in Bangladesh

If we consider the recorded history of land usage in Indian sub-continent, the purpose of the administration system has hardly changed: it remains to secure stability in relation to the division of land between individuals, groups of individuals, or other legal entities; the collection of tax revenue; surveying property; and administration, including record-keeping, land usage planning, and land judiciary (Sida, 2008). Though the administrative system in respect of land has experienced negligible change since the colonial period, the structure of the economy in Bangladesh has changed considerably over the past two centuries. The usage of land has changed from exclusively traditional agricultural and habitual purposes to including industrial and various other non-farm purposes. Despite the structural change in the economy, the importance of allocating land for agricultural usage has not been diminished as the country is also essentially dependent on agriculture for food security and employment. Hence, a well-functioning land administration and management system is critically important for the economy.

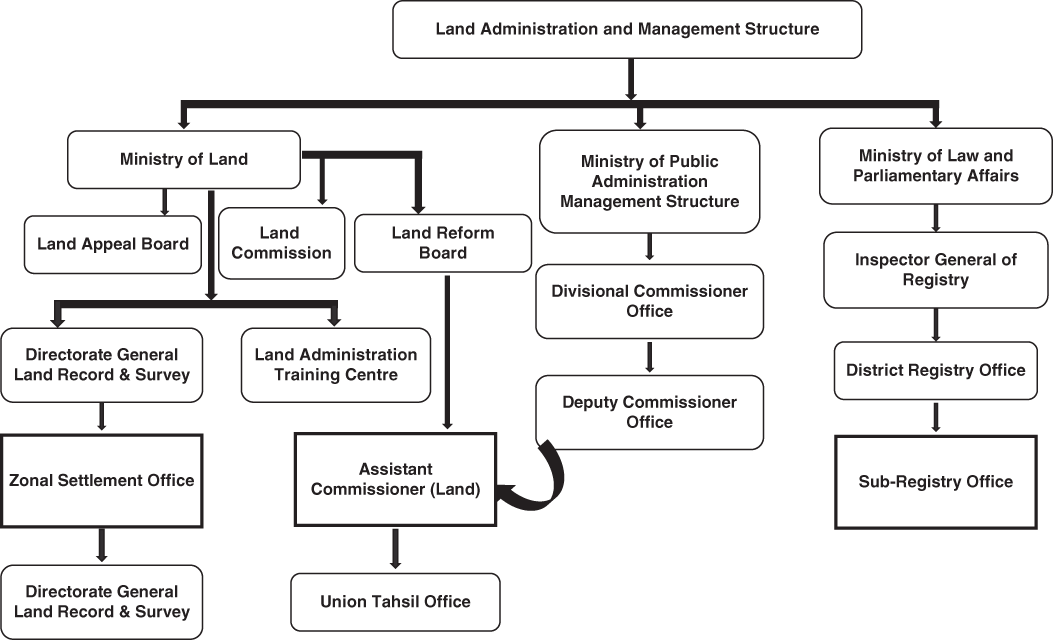

A Institutional Structure of Land Administration

The existing structure of land administration in Bangladesh is multi-layered (see Figure 8.1). The system is paper-based and maintenance of record is done mostly manually. These records are kept in different offices, which creates duplication and a lack of coherence. The land administration system in Bangladesh is managed by multiple government authorities simultaneously. These government offices are entrusted with the transfer of land rights from one party to another in sale, lease, loan, gifts, and inheritance; control of land and property development; land use and preservation; revenue gathering from land through sales, leasing, and taxes; and resolving conflicts regarding ownership and usage of land.

Figure 8.1 Land administration and management structure in Bangladesh.

The current institutional structure of land administration in the country comprises four major bodies under two ministries: the Ministry of Land, and the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs (MoLJPA). The four major bodies that administer the land management system are the Directorate of Land Records and Surveys, the Land Reform Board, and the Land Appeals Board under the Ministry of Land, and the Department of the Land Registration System (under the MoLJPA).Footnote 13 However, the Ministry of Public Administration, formerly known as the Ministry of Establishment, is authorised to appoint an Assistant Commissioner (Land), who is the responsible authority connected to both the Ministry of Land (through the Land Reform Board) and the Ministry of Public Administration (through the Deputy Commissioner’s (DC’s) office). Other government bodies that play a minor role in administering land management are the Ministry of Forests, the Fisheries Department, the Directorate of Housing and Settlement, and the Department of Roads and Railways.

There are four core stakeholders in the land administration and management system in Bangladesh:

i. The Settlement Office: The Settlement Office generally takes on the task of updating the Record of Rights. Moreover, this office is appointed with the task of preparing, printing, and distributing the mouzaFootnote 14 and thana maps of every district, defining borders among the mouzas, thanas, and districts, and providing training to the newly recruited civil service cadres working at the field level of different directorates, as well as ministries, such as the administration, land, and forest. In addition, the determination of ownership of land is done by surveying neighbourhoods every 30 years.

ii. Assistant Commissioner (Land): Under the State Acquisition and Tenancy Act 1950, the Assistant Commission of Land authorises the transfers of land rights, except during land survey. The country is administratively differentiated in various levels, starting from unions; with a couple of unions forming a sub-district or thana or upazilaFootnote 15; a couple of thanas forming a district; a couple of districts forming a division; and eight divisions forming the whole country. The land administration follows this hierarchy in a broad sense. According to a report published by the Local Government Engineering Department, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and UN-Habitat (Shafi, Reference Shafi2007), land management functions through the Commissioner at the division level, the Deputy Commissioner at the district level, the Assistant Commissioner (Land) at the thana level, and the Tahsildar at the union level. Assistant Commissioner (Land), the executing authority of the Assistant Commission (Land), discharges all the activities of the upazila land office through a detailed structured administrative system comprising various levels of clerical assistants. The Assistant Commissioner (Land) has to perform multiple responsibilities regarding land, including those of Upazila RevenueFootnote 16 Officer, Upazila Settlement Officer, Circle Inspector, Revenue Circle Officer,Footnote 17 and Revenue Circle Inspector.Footnote 18

iii. Sub-Registry Office: The Sub-Registry Office is administered under MoLJPA and is appointed with the responsibility for registering lands and other properties under the Registration Act of 1908. The Sub-Registrar is the executive authority of the Registry Office and the representative of the MoLJPA at the upazilaFootnote 19 level. The Sub-Registrar registers the transfer of land through a stamped deed declaring the property value. There are 503 Registry Offices in Bangladesh, including one in every upazila, where, on average, 7,000 land transfers occur per year. These offices provide BDT 14 billion (equivalent to US$ 165 million) in tax revenue every year, which is 0.4% of total government tax revenue; this is not managed by the National Board of Revenue (Ministry of Finance, 2019).

iv. Land Survey Tribunal: The State Acquisition and Tenancy Act 1950 lays down the provisions for the Land Survey Tribunal and the Land Survey Appellate Tribunal. In case of any disputes, for example fake documents or fake mutations,Footnote 20 the affected party files a lawsuit with the Land Survey Tribunal. In consultation with the Supreme Court, the Government appoints the judge of the Land Survey Tribunal from the Joint District Judges.Footnote 21 Against a decision of the Land Survey Tribunal, an appeal can be made to the Land Survey Appellate Tribunal, which is constituted with a judge who is or has been a judge in the High Court division of the Supreme Court.

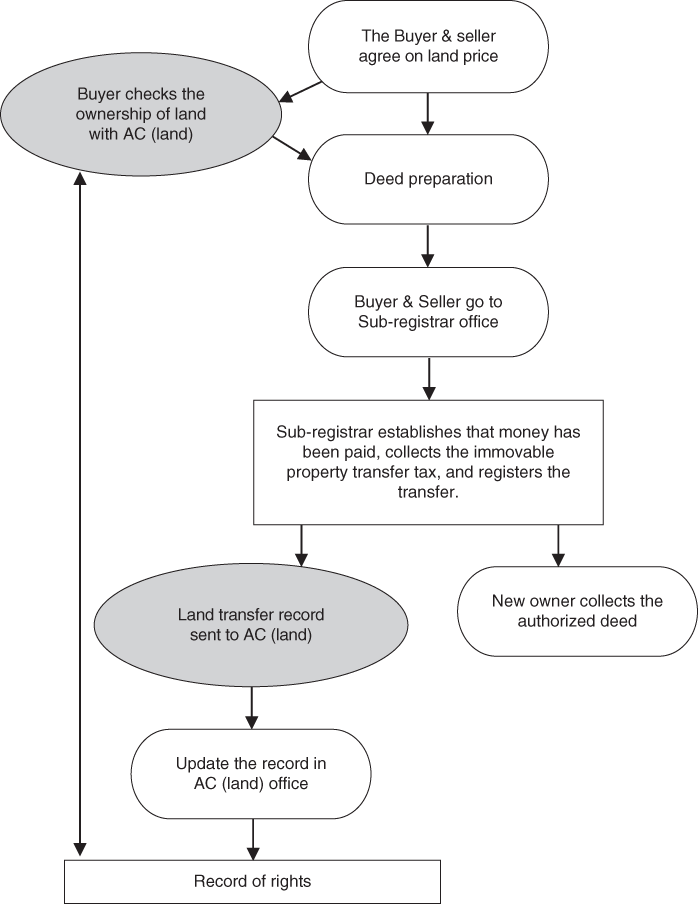

Upazila administration, which is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Public Administration, is primarily concerned with updating the Record of Rights in regard to mutation. Land buying or transfer of rights is directly connected to both the Sub-Registry Office and the Assistant Commission (Land) office. If any interested party enquires about the land that he/she intends to purchase by formally applying to the Sub-Registrar, he/she is granted the aforementioned information. Deeds are maintained by generating both alphabetically and plot number-wise ordered content so that information can be provided. When land transfer occurs, theoretically two parties have to agree on the price of the property and then the buyer will have to arrange the deed preparation. Next, both parties will visit the Sub-Registry Office together so that the Sub-Registrar can establish the money transfer between the two parties and collect the immovable property tax. The Sub-Registrar finally registers the transfer and forwards the record of land transfer to the Assistant Commission (Land) office, where the tahsildarFootnote 22 inspects and updates the record. Through this process, the Record of Rights, locally known as Khatiyan, is supposed to be updated. Moreover, buyers can check the Record of Rights from the Assistant Commission (Land) office to confirm the rightful owner of the property he/she intends to buy. Nonetheless, this land transfer has to be notified while the land survey is done by the settlement office. Figure 8.2 illustrates the land transfer procedure that would occur if the system worked properly.

Figure 8.2 The official process of land transfer in Bangladesh.

Interviews with two Sub-Registrars and two Assistant Commissioners (Land) from the Northeast and Northwest regions of the county, and FGDs with relevant stakeholders, reveal that the land transfer process often takes a detour in the steps involving the Assistant Commission (Land) office. Inherited lands are not mutated properly in most cases, due to lack of awareness among the landowners. In some cases, land mutation of sold land goes through years of red tape, ultimately reaching the DCs’ office from the upazila land office via the local tahsil office (revenue office). Often the process of the Registry Office sending the land transfer record to the Assistant Commission (Land) office takes too long, and sometimes it does not take place at all. The lack of timeliness in the process results in a lack of coherence of information between the stakeholders. Therefore, the possibility of multiple landowners existing in different government records for the same property arises, creating the opportunity for fraudulent activities and litigation. When a potential buyer attempts to check the ownership of the property, the information he/she obtains from Assistant Commission (Land) office might not be synchronised with the information in the Registry Office. The buyer can obtain information from the Assistant Commission (Land) office only, limiting his/her chance of comparing the information regarding ownership of the property. In this way, forgery and intentional multiple-selling of the same land can take place.

B Challenges Related to Land Administration

The land administration system in Bangladesh is characterised by pervasive corruption, incidents of land-grabbing by vested interest groups and influential politicians, and social tensions emanating from land-related conflicts. The land management system in Bangladesh is still based on traditional regulations, with most of the rulebooks framed during the British period. Therefore, inefficiency in the provision of legal and administrative services related to land intensifies corrupt practices in this sector. Box 8.2 sets out some examples of corruption in the land administration system in Bangladesh that have been discussed in the national media.

Box 8.2 Recent examples of corruption in the land system in Bangladesh published in the media

Case 1: The land surveyor demanded US$ 825.63 for providing a digital Record of Rights to a service seeker, with US$ 236.20 having to be paid in advance. (The Business Standard, September 2019)

Case 2: A deputy assistant officer from the union land office was caught red-handed with US$ 176.92 in bribe money. (The Business Standard, October 2019)

Case 3: One surveyor was caught with US$ 109,834.51 and documents proving incidents of bribery, with 29 other employees from the same Land Acquisition department involved. (Dhaka Times, Jugantor, Manab Zamin, Daily Janakantha, Bangla Tribune, Prothom Alo, Ittefaq, February 2020)

Case 4: A land officer from the union land office demanded five times ($59.05) the original fee ($13.82) as a bribe. (Jugantor, Dainik Amader Shomoy, Jago News24, October 2019)

Case 5: A land officer from the union land office took US$ 59 for providing a tax receipt for US$ 2.36. The bribes for the mutation of vested property amounted to US$ 1.771.52; for mutation in general, it was between US$ 240 and US$ 2,400; and for leasing it was US$ 710. The officer allegedly harassed the service seekers, threatening to delay the mutation by confiscating documents unless the bribe was paid. (Prothom Alo, June 2019)

Case 6: According to TIB, the amount of the bribe for mutations was 50–60 times the original rate. In one example, a service seeker mutated the name by paying a US$ 300 bribe. The employees, along with the middlemen, solicited bribes, according to the service seeker. 50% of the bribes went to the Sub-Registrar, and the rest was divided among other employees. (BBC Bangla, September 2019)

Case 7: A bribe for providing compensation for land acquisition: surveyors took 30% of the compensation as a commission or bribe from the afflicted owners, in exchange for providing the compensation. (Aparadh Bichitra, February 2020)

Case 8: In an upazila land office, land-related documents were ‘misplaced’ unless a bribe was paid. The rate of bribes differed depending on the service seekers’ economic situation, profession, influence, and connection to elites. In the Sub-Registry Office, the middlemen had access to the official documents to the same extent that they performed various duties, such as keeping records in the record room. (Dhaka Times, September 2019)

Case 9: The Chattogram district administration made a contract with BBC Steel Company and leased 7.1 acres of land of coastal forest despite a court order forbidding this. (The Business Standard, January 2020)

Case 10: In a period of two years, one afflicted landowner, a day labourer by profession, was subjected to 70 litigations by a local neighbour, locals with connection to political elites, and business elites. (Prothom Alo, May 2019)

Figure 8.3 provides a schematic representation of the complexities of land administration, and the respective consequences in Bangladesh. The land-related challenges occur for two main reasons: internal issues (e.g. a lack of adequate infrastructure, the analogue records system, and inconsistent human resources) and external issues (e.g. lack of coordination among the administrative entities). The subsequent sub-sections provide an analysis of these challenges.

Figure 8.3 A schematic presentation of the complexities in land administration, and their consequences.

1 Internal Administrative Issues

Internal administrative problems relating to the stakeholders, from infrastructure to analogue record-keeping, arise from the inability to modernise the system, which is a hold-over from the inherited colonial system. Key informant interviews (KIIs) with relevant stakeholders, conducted in July 2019, highlighted the following internal administrative issues.

Lack of digitisation: Both the Ministry of Land and the Ministry of Law lack necessary digitisation. However, copies of Records of Rights and mutation of names are in the process of being digitised in the Ministry of Land. The Government initiated an electronic application system for the mutation of names, or e-mutation, in 485 upazilas and 3,617 union land offices in 61 districts, barring the three hill districts in the CHT, on 1 July 2019. However, over 40% of the upazilas underperformed in the e-mutation process, and three districts from the CHT are yet to be included in the process.Footnote 23 The official reason given for this underperformance is that it has been hard for staff to adapt to the new technology. Moreover, a grievance redress system, in the form of a hotline, was initiated in 2019. However, the hotline only aims to accept complaints, it cannot guarantee the resolution of them.Footnote 24 People often find themselves paying more than required. Also, corrupt officials at land offices harass service seekers, and threaten to delay mutations by confiscating documents unless a bribe is paid. There is resistance to the digitisation of the system by vested interest groups.Footnote 25

Infrastructure: According to the present law, only the deeds from the current year are supposed to be retained in the Sub-Registry Office. Nevertheless, these offices are preserving all deeds from 1987 onwards, due to the unavailability of space in the district offices. The deeds are stored in old and damp record rooms, causing them to deteriorate. The records are vulnerable to fire or other hazards, which will turn the main document held by the owner into the only evidence available. A lack of proper duplicates or backups is causing legal complexities due to lost deeds and record books. Moreover, presently, there is a record book crisis in the Registry Offices. The Registry Offices are constrained to collect deeds without proper records due to the lack of record books. Record books (locally known as Balaam Boi) are not provided to the Registry Office for years, even after communicating repeatedly with the MoLJPA. In Dhunat upazila of Bogra district, the collection of property tax by union land offices was postponed for more than a month due to a lack of receipt books.Footnote 26 This lack of receipts stopped the land transfer process and relevant people getting loans from the banking system, since such receipts were required as legal documents to obtain bank loans secured against any property. Also, in most cases, inadequate logistics and transport facilities restrict the settlement offices from conducting their regular responsibilities, such as monitoring of land record surveys.

Human resources: There exists a lack of manpower within several posts of various departments of the land offices, constraining the required services provided to people. The currently employed manpower also has a wide skills mismatch. The settlement offices lack updated training regarding the land survey methodology (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2015). Though the participation of non-government organisations and academia in land-related policy consultations has been on the rise, the participation of the private sector in technical aspects of land management remains limited. Therefore, the precision and transparency of surveys is widely discredited after land surveys are conducted (Hossain, Reference Hossain2017). Here, the self-interest of various stakeholders prevents the system from working efficiently. For instance, the lack of necessary manpower in the Registry Offices is made up for by unofficially employed human resources, who are employed through nepotism and corruption; the latter harass the service seekers by multiplying official registration fees.Footnote 27 The author’s interview with a Sub-Register in Dhunat upazila of Bogra district suggests that, for that specific Registry Office, there are 87 copyists, with more than 100 assistants, whereas only 20 copyists were required.

2 External Administrative Issues

The second reason behind the administrative complexities can be described as the lack of coordination among the stakeholders. The administrative offices that are bestowed with the responsibility for land management work separately, with little coordination among them. The Sub-Registrar registers the land after checking the record of the settlement office and the mutation of the Assistant Commissioner (Land). Additionally, a land transfer notice is supposed to be sent to the Assistant Commissioner (Land) office If any work is registered in the registration office. However, in reality, the records are hardly ever updated due to the lack of coordination between these two offices. The mutation of land is performed by the Assistant Commissioner (Land) whenever someone submits the registered documents, regardless of whether they receive a copy from the Sub-Registry Office. Therefore, a multiplicity of documents or Records of Rights arises due to the lack of coordination inside the land administration system (Hasan, Reference Hasan2017).

Evidently, a gap exists between land management by the Ministry of Land and the registration of land by the Ministry of Law. An expert committee suggested to address this gap by developing a database, using appropriate technologies for coordination, and introducing a Certificate of Land Ownership as the sole document for registering land ownership (LANDac, 2016). However, until now, there has not been any progress on this front.

3 The Results of Administrative Complexities

Internal and external administrative complexities lead to unidentified khas land, lack of access to information, corruption, congestion of legal disputes, and multiple transfers of land.

Unidentified khas land: Since the colonial period, this region has experienced people abandoning their land due to communal riots, war, etc., which has led to the Government being assigned the abandoned land. Many areas of khas lands, khas water bodies, khas ponds, enemy property, abandoned property, as well as unused land under different government offices, are not properly identified and reported by the land administration. Around 70% of the farm households in Bangladesh have less than 1.5 acres of land, which means a large portion of these land-poor households depend on seasonal employment opportunities or sharecropping, including other tenancy arrangements, to access land for their livelihoods (Hossain, Reference Hossain2017). The aforementioned khas land, which could be used to maximise social welfare by distributing it among the landless and land-poor population, or investing in development projects, often gets misused, due to administrative complexities, such as a lack of manpower to identify and report it, fake documents submitted fraudulently to the Registry Office or Assistant Commission (Land) office, and simply grabbing of the land by influential people (Barkat, Reference Barkat2005). Obtaining and retaining khas land is a complex issue for land-poor and landless people who need it the most and who require assistance to expand their land ownership (Barkat et al., Reference Barkat, Zaman and Raihan2001). A lack of manpower, along with a lack of transport facilities, to periodically monitor land and verify the field reports after monitoring exponentially extends the volume and extent of misuse of khas land (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2015).

Lack of access to information: As Rahman and Talukder (Reference Rahman and Talukder2016) argued, administrative complexities, such as lack of digitisation, complicates the whole process of accessing the information related to land ownership. Demand to access land tenure records, land information, and land documents often produces very little results. The level of access to land data and related information by the mass of people remains low, hampering the fulfilment of the right to information. The updating and sharing of information among stakeholders is virtually ineffective due to the lack of effective coordination among government agencies. The lack of access to information perpetuates a lack of awareness among the general population. A general population who lack awareness cannot protest or demand their rights. In addition, they cannot demand a modern land administration system. Therefore, government efforts to solve the issues are often not implemented, due to people being unaware of the issues.

Corruption: Red tape in land administration causes corruption. Since citizens are mostly unaware and unable to access services without paying bribes, they end up being part of the corrupt practices. According to a nationwide survey conducted by Transparency International Bangladesh (2015), 16.6% of households resorted to the land administration, and 59% of them were victims of corruption. According to the same survey, 54.9% of the households paid a total of BDT 22.61 billion (around US$ 0.27 billion) as bribes in 2012, 1.6 times higher than the land revenue collected in 2019. According to another survey, conducted by MJF, Uttaran and CARE Bangladesh in 2015, around two-third of households (65%) did not receive the services required from land offices, or were asked for bribes, or received services late.Footnote 28 Moreover, agricultural land is often used for unplanned real estate and industrial purposes, by resorting to bribes or political influence (LANDac, 2016). As part of an overall study of the institutional diagnostics of development in Bangladesh, a survey (SANEM-EDI survey in 2019, see Chapter 3) was conducted among 355 respondents covering major stakeholders in Bangladesh. According to the survey results, almost 90% respondents indicated that land-related operations at the local community level were subject to corruption.

Congestion of legal disputes: In the absence of an effective governance system capable of resolving land-related disputes, the reliance on litigation without administrative process leads to legal disputes. The presence of a multiplicity of legal documents perpetuates disputes over land, which comprise almost two-thirds of the total legal disputes in the country, resulting in about 1.7 million pending cases as at 2014 (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2015). On average, 2.5 million new mutation-related cases are created every year.Footnote 29 Moreover, land-related disputes are dealt with by the Land Survey Tribunal, which lacks sufficient manpower to deal with the enormous congestion of legal proceedings. The SANEM-EDI Survey in 2019 found that 65% of the respondents held the view that the implementation of land laws was very poor in Bangladesh.

Multiple transfers of land, and land-grabbing: FGDs and KIIs reveal that due to the lack of coordination among the administrative entities involved in the land transfer process, the possibility of selling land multiple times arises. A buyer’s failed attempt to update the record manually in the Assistant Commission (Land) office inevitably results in a multiplicity of land-related documents and a multiplicity of ownership, causing disputes in the long run (Hasan, Reference Hasan2017). This phenomenon is common in relation to applications for compensation from the Government during the acquisition of land for development purposes, as various political opportunists and previous owners claim to be the real owners of the land. Also, wealthy and influential people encroach on public lands using false documents and obtain court decrees to confirm their ownership, often with the help of officials in the land administration and management departments (Feldman and Geisler, Reference Feldman and Geisler2011).

4 Investors’ Opinions about Land Operations

Unavailability of serviced land is a prominent investment hurdle in Bangladesh (World Bank, 2012). Investors’ opinions about land operations in Bangladesh can be ascertained from the Doing Business Index of the World Bank. Bangladesh ranked 168 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s Doing Business Index in 2020, while India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan ranked 63, 108, and 99, respectively. Among the Doing Business indicators, the Registering Property indicator considers four distinct areas comprising ‘number of procedures’, ‘amount of time (days)’, ‘the cost required to register a property’, and ‘quality of the land administration index’. In Bangladesh, registering property requires eight procedures (around 1.2 times more than the South Asian average), takes 264 days (more than twice as long as the South Asian average), costs 7.2% of the property value (around 1.1. times higher than the South Asian average), and the quality of the land administration index is 6.5 (around 74% of the South Asian region’s average). All of these results suggest that the performance of the land operation system in Bangladesh, as perceived by investors, is lagging behind that of its neighbouring countries.

C Dynamics of Political Power and Institutional Configurations

The complexities of land administration and management are greatly compounded by the political economy, which prevents problems from being solved. The more explicit scenario includes land-grabbing and congestion of litigation, for which politically influential groups and the beneficiary business elites are directly responsible.Footnote 30 Furthermore, in many cases, the same parties have created internal and external issues related to land administration, as already discussed.

The recruitment procedures for the land administration are beset by corruption and nepotism.Footnote 31 Due to the corrupt recruitment process, including bribing and enforcing political influence, the recruited manpower in the land administration system is mostly inefficient, unenthusiastic about the service they are required to provide, and prone to further corruption. KIIs and media reports reveal that there are unnecessary numbers of employees who are overcharging people in the Registry Offices.Footnote 32 As discussed before, while digitisation can solve some of the administrative problems, including corruption, the KIIs suggest that digitisation would decrease the number of currently employed people, and there is a resistance to such reforms from vested interests. Also, these vested interests are closely linked to the local politically influential elites, who are also the beneficiaries of the rent being generated from the corrupt practices in the land offices (Chowdhury and Panday, Reference Chowdhury and Panday2018). Due to the substantial benefit from corruption, Sub-Registrars are generally reluctant to be promoted to district-level registrars. The reasoning for this also partially lies in the lack of capacity bestowed upon a District Registrar as well.Footnote 33

The issues related to infrastructure, congestion of legal disputes, access to information, fake documents, and the manpower required to manage the whole chaotic current process can be improved by digitisation. However, despite the overwhelming consensus about the necessity of digitisation, the self-interest of various stakeholders with political influence, who are directly benefitting from the current system, prevents the system changing for the better. These interest groups of politically influential people and business elites with political connections are directly or indirectly involved in the corruption related to land tax submission procedures, land registration procedures, mutation of ownership, changing land type to acquire an unjustified price from potential industrialists and other buyers, selling water bodies to uninformed buyers, and unnecessary bureaucratic complexities.Footnote 34 According to the Minister for Land, as reported in a newspaper article, land surveys are entangled with corruption to such a degree that surveys provide millions to the people who are involved in the process, and they are ‘ruthless’.Footnote 35

While some business elites are in favour of reforms of land management, the ruling political elites are not very keen as reforms would eliminate sources of rents, including among Assistant Commission (Land) and Sub-Registrar employees, who are likely to be there because of loyalty to the ruling political elites. However, powerful business elites with strong political connections are able to bypass the system.

V Addressing Land-Related Problems Through Sezs, and the Institutional Challenges of Land Acquisition for Sezs

As discussed earlier, registering property is very difficult for new investors, especially if they lack a connection to the political elites. Moreover, the high land price causes high input costs, which bar potential investors. Identifying and acquiring suitable land is also challenging for private investors, and especially for foreign investors. At present, private investors can access land through the existing land system, which is full of institutional weaknesses, as discussed above. To solve these issues and enhance private investment, the Government created Export Processing Zones in 1983, with preferential treatment given to the labour-intensive ready-made garment sector. However, EPZs catered only to export-oriented industries. Hence, the Government initiated SEZs, through the Bangladesh Economic Zone Authority (BEZA). The SEZs offer a prospective solution, among other things, to the challenges faced by new investors in accessing land.

A SEZs in Bangladesh

SEZs are geographically delineated ‘enclaves’ in which the regulations and practices related to business and trade differ from the rest of the country, and therefore all the units located therein enjoy special privileges (Raihan, Reference Raihan2016). According to Ge (Reference Ge1999), SEZs are characterised, in general terms, ‘as a geographical area within the territory of a country where economic activities of certain kinds are promoted by a set of policy instruments that are not generally applicable to the rest of the country’. Theoretically, SEZs are supposed to accommodate both export-oriented and domestic market-oriented industries.

Under the Bangladesh Economic Zones Act, 2010, BEZA was established as the public regulatory body for implementing SEZs. Till now, BEZA has approved 88 SEZs, through its governing body, which comprises 59 government SEZs and 29 private SEZs.

BEZA has started to work on four types of SEZs: government, private, public–private partnerships, and foreign. Feasibility studies, land acquisition, area-specific social and environmental studies, and other initiatives are underway for these approved SEZs. There are plans to acquire approximately 75,000 acres of land for these SEZs. By 2030, BEZA expects to create employment for about 10 million people and to export US$ 40 billion worth of products annuallyFootnote 36 by establishing 100 economic zones nationwide.

Although BEZA plans to establish SEZs in 31 districts, most of the projects are situated within Dhaka and Chattogram region. Regardless of the authority given to BEZA, there is a need for concerted effort from all the state stakeholders to implement its plan. The SEZs require a massive amount of land acquisition, which concerns all the stakeholders of land administration. Although BEZA is supposed to ease the complications in respect of accessing land, pace has been slower than expected.Footnote 37

Among the private SEZs, so far success has been seen in the case of the Meghna Industrial Economic Zone, which is located beside the Dhaka–Chattogram highway. Situated on 110 acres of land, in February 2020, this economic zone started its operation with nine new industrial units (related to consumer products and industrial raw materials), at a cost of BDT 40,000 million (around US$ 0.5 billion).Footnote 38

B Challenges in Land Acquisition under SEZs

Land acquisition in a densely populated and land-scarce country like Bangladesh is always a complex task. Therefore, the success of the SEZs policy will depend on the way the institutional challenges in the land administration system are handled. At the same time, the tempting facilities of SEZs present the possibility of relocating firms for rent-seeking reasons (Razzaque et al., Reference Razzaque, Khondker and Eusuf2018).

Land acquisition refers to the process by which the Government forcibly acquires private land for a public purpose with or without the consent of the owner of the land, compensating the owner in exchange for the aforementioned land in an amount which can be different from the market price of the land.Footnote 39 Land acquisition is intricately connected to development blueprints envisaged by the Government of Bangladesh, such as its five-year plans, the Delta Plan, and so on. Additionally, appropriate land acquisition procedures assist in the timely execution of development projects. According to the KIIs with land owners and officials of the land office, legal owners are regularly harassed and exploited at the land offices throughout the country. Moreover, the financial compensation related to land acquisition perpetuates an overwhelming amount of corruption around the DC offices of the country. Many development projects are hindered for years due to land acquisitions and the corresponding compensation process.

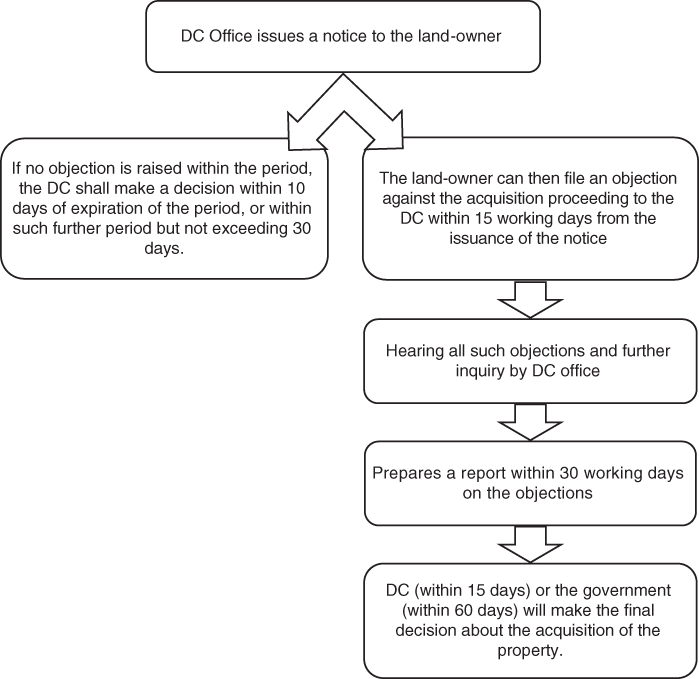

In this context, the land acquisition process for SEZs required clarification in order to resolve the complex issues surrounding compensation. In this context, the Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Act 2017, currently used by BEZA for land acquisition, was developed to replace the Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Ordinance 1982, which in turn was descended from the Land Acquisition Act 1894, established during the colonial period. In the 2017 Act, a detailed clarification is provided of the compensation process. Although the Ordinance of 1982 prohibited the state from evicting people from their homesteads, the vagueness of the law obstructed marginal people from receiving compensation. However, the 2017 Act also needs further amendment to solve complexities at the ground level.

As the success of SEZs depends on effective land acquisition, the land acquisition process for SEZs needs to be different from the usual land acquisition processes applied for any other purposes. However, our FGDs and KIIs confirm that the land acquisition process for SEZs has not been very different from the usual process, and it suffers from several of the corrupt practices related to land administration and management mentioned in Section IV. For example, in the land acquisition process, while the last owner of the deed, whose name has been mutated and who provides revenue receipt, should be treated as the actual owner of the land, corrupt officers in land offices send the land acquisition notice to various previous owners and thereby complicate the situation. In this process, opportunists, in association with corrupt officers in the land offices, file claims for compensation for the acquisition of land. In the end, the actual owner of the land has to bribe the corrupt officers in the land office to provide the compensation.

Our FGDs and KIIs also reveal that the news of a land acquisition causes hasty construction to acquire higher compensation for the hollow land by opportunists, in order to obtain higher compensation.Footnote 40 People who do not have any connection with political elites are forced to pay bribes in order to receive compensation. However, a bribe often does not ensure the compensation. Filing for compensation can lead to encounters with influential goons and middlemen who seek to snatch away the money. The presence of intermediaries or middlemen in the land acquisition offices worsens the woes of the actual owners. Intermediaries distribute bribes to the different levels of employees in the land acquisition office.Footnote 41

One example of the aforementioned difficulties in land acquisition for SEZs is the Sreehatta Economic Zone. The presence of fake landowners, a mismatch in the price of land, and inadequate compensation angered villagers, who filed hundreds of cases in the courts, delaying the zone’s development.Footnote 42

C Sreehatta Economic Zone: An Example

Sreehatta Economic Zone is located in Moulavibazar district (Northeast of Bangladesh), which is to the east of Sylhet, west of Habiganj, north of Sunamganj, and south of Moulavibazar district. This SEZ was established on 352 acres of land in Sherpur at Sadar upazila, with a view to generating employment for 44,000 people in the Sylhet division. In March 2017, six private entities invested US$ 1.4 billion to establish their industries in this economic zone. Moreover, land development, utility supply, and lake development have already started in this zone under the supervision of BEZA. Figure 8.4 depicts the land acquisition process of SEZs under the Ordinance of 1982. Sreehatta Economic Zone acquired 240 acres of land from approximately 2,000 families and the remaining 112 acres from government khas land.

Figure 8.4 Land acquisition process.

While maintaining the valuation methods described in the Ordinance of 1982, the process takes into account whether the land is used for agriculture, habitat, and so on. The overall value also depends on the details of the usage, that is the type of crop being cultivated on the land. For the Sreehatta Economic Zone, the Sub-Registrar’s office determined a market price of BDT 34,600 per decimal of Aman landFootnote 43 and BDT 66,700 per decimal of Aus land.Footnote 44 Generally, the responsible DC office requires assistance from the Housing and Public Work Division, Agriculture Division, and Forestry Division to determine the value of infrastructure, food, crops, and trees, respectively. According to the Ordinance of 1982, the affected owners should get 150% of the market price as compensation. Although in Sreehatta Economic Zone, around 85% of total compensation has been paid, it took three to four years for the amount to be paid, revealing the challenges faced by the owners. Thus, closer inspection of marginal landowners’ cases reflects the critical situation in the land acquisition process. Also, as mentioned earlier, hundreds of cases were filed in the courts related to confirming the legal ownership of the acquired land.

As mentioned earlier, the Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Act 2017 replaced the Ordinance of 1982. But the late implementation of the new law prevented many people obtaining fair compensation in the case of Sreehatta Economic Zone. The landowners accused the Assistant Commission (Land) of undervaluing the land price since the then market price of agricultural land was more than the price determined by the Assistant Commission (Land). Moreover, according to the Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Property Act 2017, if in consequence of the acquisition of the property, the affected person is compelled to change his/her residence, reasonable expenses, if any, incidental to such a change must be considered in determining compensation. However, there are allegations of violations of these provisions in the case of the compensation provided to the landowners in the case of Sreehatta Economic Zone.

We investigated the land acquisition cases of two people: E and T, who are brothers. They live in Sherpur village at Sadar upazila in Moulvibazar District. About 7.66 acres of land were acquired from them for the purpose of Sreehatta Economic Zone. Out of this 7.66 acres, 1.52 acres was agricultural land (Aman) and the remaining 6.14 acres included a homestead, pond, and plantation. The two brothers received BDT 7.81 million (after deducting taxes, including income tax) as compensation for 1.52 acres of agricultural land (Aman type), on the basis of the compensation of per decimal land was BDT 51,000 (150% of the market price determined by the Assistant Commission (land)). They also received around BDT 12.9 million as compensation for infrastructure, trees, food, and crops. However, the compensation for the 6.14 acres of homestead land is still unpaid. Since there was a legal dispute in the High Court regarding these lands, the payment was stalled by the DC’s office at the time of payment. During the valuation process, the Assistant Commissioner (Land) categorised the lands (6.14 acres) as agricultural land and accordingly the total unpaid amount was BDT 32.63 million. Since the land from the aforementioned economic zone was acquired under the old law, that is the Ordinance of 1982, the landowners (E and T) were dissatisfied with the valuation process. Therefore, as the aforementioned land was homestead type and located beside the road, they claimed further compensation and rehabilitation support. After formally complaining to BEZA, they received only indifference, and presently the situation is at an impasse.

VI Way Forward

The research underlying this chapter suggests the following measures, both at the policy and institutional levels, for the improvement of land administration and management in Bangladesh.

An efficient land survey: The land management system of Bangladesh still accepts Cadastral Survey, State Acquisition Survey, and Revisional Survey records due to a lack of updated surveys conducted in recent times. The land survey and documentation process need to be efficient and credible. The survey process requires updating in regard to survey methodology and technology, and there is a need to train relevant employees.

Digitisation of record-keeping: The analogue colonial method of record-keeping perpetuates the multiplicity of documents and corruption. The colossal infrastructure necessary to preserve the analogue record creates an array of problems in itself. Therefore, digitising the whole record-keeping documentation process is essential.

Administrative reforms: Rigorous administrative reform is a precondition for mitigating challenges regarding access to land. The current administrative system of colonial descent has to be modified, keeping the context of the country in mind. The Land Administration Manual needs to be updated, and land administration needs to be capable of handling land-related disputes. Administrative reforms can be piloted in specific offices and further extended nationwide if they succeed.

Harmonisation of different stakeholders with overlapping responsibilities: Different stakeholders with overlapping responsibilities need to be harmonised based on their functioning. The recommendation of the Muyeed CommitteeFootnote 45 to combine Land Registration (Sub-Registrar) and record (tahsil) offices into a single office at the field level needs to be implemented

Allocation of public lands: A higher degree of coordination should be achieved at the national level to allocate public land to ensure its most productive and essential use. This could be achieved through a coordination institution or body and the establishment of a public land database that would list all plots available for development by location, size, facilities, and other attributes (UNCTAD, 2013; Kathuria and Malouche, Reference Kathuria and Malouche2016).

Reform of the judicial process: The judicial process needs to be reformed to resolve the congestion of litigation. Land survey tribunals need to be reformed to resolve contemporary land–related litigation. Land survey tribunals should be composed of three members involving representation from the judiciary, settlement department, and land administration.

Building awareness: Access to land is difficult to achieve for the general population due to the lack of information regarding the land administration system and the services provided by them. The land laws need to be translated into colloquial Bangla to build awareness. Furthermore, setting up a one-stop service centre to provide information and primary guidance, coupled with digitised administration, can improve the overall land-related problems among the mass of the population.

The present land administration system in Bangladesh has been inherited from the colonial era and fails to meet the needs of the present. The archaic land management system and land laws require modernisation, and there is a need for well-functioning institutions. To increase the effectiveness and credibility of reforms, the Government should also focus on the alignment of cross-sectoral policies (National Agricultural Policy, National Rural Development Policy, National Forest Policy, and Coastal Zone Policy). Entrusting one single agency with sufficient capacity to maintain spatial records in rural and urban areas would be beneficial.

While the Government of Bangladesh has adopted the strategy of establishing SEZs to address the land-related problems facing domestic and foreign investors, the success of SEZs will require an efficient mechanism of land acquisition. While some laws and administrative procedures have already been laid out to provide assistance to SEZs, the progress made so far needs to be critically examined to achieve long-term success.