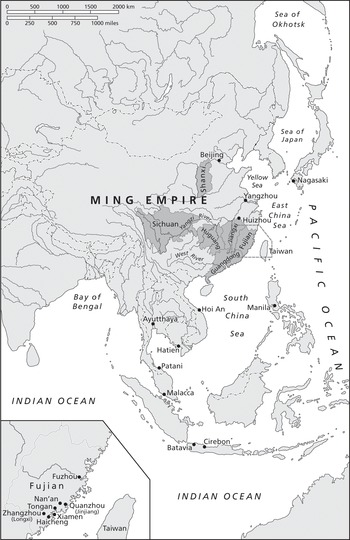

Although Chinese had for centuries ventured abroad, the presence of Chinese overseas became much more marked between 1500 and 1740, a period that roughly corresponds to what scholars of global history conceive of as the early modern period. Tombstones provide one means of tracing this expanded overseas presence. Take, for example, Longxi County, the seat of Zhangzhou Prefecture in southern Fujian province. One of the earliest tombstones in a Chinese cemetery at Nagasaki, Japan, was erected in 1641 for a Longxi man who likely died four years earlier. At a Chinese cemetery in Malacca, on the Malay Peninsula, one finds the 1678 tombstone of Longxi native Zheng Fangyang, a leader of the Chinese community in Malacca. Numerous tombstones of Longxi natives are located on the island of Java, including two at Cirebon, a port city on the island’s north coast. One is a 1701 tombstone for Longxi native Xu Gongxian, erected by his four sons and two grandsons. A year later, in the same graveyard, the son and two daughters of Chen Kuanguan put up a tombstone for their father. These and other tombstones suggest that migrants from Longxi County during the early modern era were not only active as traders but indeed had settled far from their native place, across a 5,000-kilometer swath of maritime Asia from southwestern Japan to the southern Indonesian islands. This book begins with the emergence of substantial diasporic trajectories in the early modern period, beginning in the sixteenth century, during the latter half of China’s Ming dynasty. It was during this period that sustained, identifiable patterns emerged, that institutions formed, and that evidence can be found of families in specific communities such as Longxi County adopting cultures of migration.Footnote 1

Of course, internal Chinese migration long preceded the sixteenth century. Migration from north to south was an important factor in a demographic shift from the Yellow River basin, the population center of China in the early imperial dynasties, to the Yangzi River basin, the population center during the later imperial dynasties. By Ming and Qing times, many of the lineages in the southeastern coastal provinces of Fujian and Guangdong that sent migrants overseas claimed that their founding ancestors had centuries earlier migrated from northern China.

A large proportion, perhaps even a majority, of internal migrants moved independently of state initiatives. Nevertheless, the imperial state could play an important role in organizing the movement of migrants within its borders. This was especially so in the early Ming dynasty. In the aftermath of rebellions that led to the downfall of the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) and the founding of the Ming, the new regime forcibly resettled large segments of the population to reclaim barren land in some areas, to populate new imperial capitals in Nanjing and Beijing, and to staff military garrisons on the empire’s frontiers and other strategic places.Footnote 2

Likewise, one could begin a study of external Chinese migration before the sixteenth century. As with internal migration, the state sometimes played an important role in external migration. A transition from the rule of one regime to another often created refugees out of those loyal to the collapsing regime. In this and the following chapters, we will find examples during the years surrounding the fall of the Ming dynasty, of the Qing dynasty, and of the Republic of China (1912–1949). Migration beyond the borders of the empire might also occur as a result of wars of expansion. For example, some Chinese are thought to have settled in Java after the ultimately unsuccessful Mongol Yuan invasion of the island in 1293. Likewise, the Ming conquest and subsequent annexation of northern Vietnam in 1407 brought tens of thousands of Chinese into that country as soldiers and administrators until 1427, when the country regained its independence. Roughly contemporary with Ming intervention in Vietnam was a series of seven maritime expeditions led by the Ming eunuch Zheng He. Between 1405 and 1433, massive Ming fleets visited ports throughout maritime Southeast Asia and across the Indian Ocean to the Arabian Peninsula and the east coast of Africa.Footnote 3

Nevertheless, overseas Chinese migration has for the most part not been organized by the state, and this was also true for early Chinese migration. Rather than paving the way for later Chinese merchants in maritime Southeast Asia, Zheng He’s ships in fact followed routes already established by Chinese overseas traders, most of whom hailed from the province of Fujian. By the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Fujianese, or “Hokkien” (a term derived from the Romanization of “Fujian” pronounced in the southern Fujianese dialect), had established themselves as maritime merchants in Southeast Asia; some Fujianese traders were also active in Japan. These Hokkien seafaring merchants for the most part remained based in Fujian rather than settling overseas. Nevertheless, by the fifteenth century, several contemporary accounts suggest, there existed burgeoning communities of Chinese traders, mostly Hokkien but also Cantonese (broadly referring the people from Guangdong province, more narrowly from the Pearl River delta in south central Guangdong) on the islands of Java and Sumatra, in the kingdom of Siam, and at the sultanate of Malacca (Melaka), on the Malay Peninsula.Footnote 4

The sixteenth century represents an important turning point because during this century the unregulated movement of merchants and migrants became more common, and is more readily seen in historical sources. Equally important, new genres of texts, such as the 1570 route book, served this increasingly mobile population. In such sources one finds traces of diasporic institutions and family practices that would become increasingly common in later centuries.

Increased unregulated mobility stemmed from some important social changes in China that became prominent by the sixteenth century. A number of factors, ranging from Ming frontier defense and financial policies to an influx of silver from Japan and Spanish America, stimulated commercialization and monetization of the economy. These changes made the export of male labor a logical strategy for family socioeconomic maintenance. For example, the main tax during the Ming was an agrarian tax. In the early Ming, this tax was paid in kind, both in the form of grain and as labor service for the state. By the sixteenth century, these two forms of taxation were more commonly converted into a single payment in silver. It thus became possible, and perhaps even desirable, for a family to send an adult male away from home to work as a hired agricultural laborer, a miner, an apprentice, or a merchant. The export of male labor for family economic sustenance thus became increasingly common. The spread of New World crops in China brought about other social changes in the sixteenth century. In southern China, where the staple crop was rice, New World crops such as maize and peanuts could be cultivated in mountainous and sandy lands where rice could not. The cultivation of New World crops encouraged family migration to open up highlands in the interior of China and to its western and southeastern frontiers. Demographic growth stemming from commercialization of the economy and relative political stability in the sixteenth century, and a resulting land shortage, also encouraged outward migration from China proper, both of male laborers and of entire families.Footnote 5

Early Modern Chinese Trade Diasporas

Historians describe the most prominent diasporic trajectories that emerged in the early modern period as trade diasporas. One influential historian of African and world history defined a trade diaspora as a dispersed network of “commercial specialists” who “would remove themselves physically from their home community and go to live as aliens” in other towns, often important commercial centers far removed from their home communities. Learning the language and customs of their host communities, these long-distance merchants served as “cross-cultural brokers” who oiled the emerging global economy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Similar to the notion of trade diaspora, Wang Gungwu, the pioneering scholar of overseas Chinese migration, proposed the “merchant pattern” as the dominant mode of overseas Chinese migration in the early modern era. According to Wang, most Chinese migrants in this period were “merchants and artisans (including miners and other skilled workers),” who typically pursued their trades in the “ports, mines, or trading cities” of maritime Asia. Many were partners, or agents of commercial firms, or members of extended families or lineages, based in emigrant communities along China’s southeast coast.Footnote 6

Accordingly, early modern Chinese trade diasporas were never made up exclusively, or even primarily, of merchants. In a 1590 letter to the king of Spain, for example, the Spanish bishop of Manila described Chinese there not only conducting the famous long-distance trade but also working as doctors and apothecaries, as tailors and shoemakers, as stonemasons and other craftsmen, as market gardeners, butchers, and bakers, as fishermen and fishmongers, and as proprietors of “eating houses” that served Chinese, indio, and Spanish customers. Thus, even though prominent merchants in trade diasporas often left the largest traces in historical records, whether in Chinese cities or in overseas ports, many trade diasporas included migrants, mostly males, from across the socioeconomic spectrum. Aside from prominent merchants, one might find commercial apprentices, domestic servants, and unskilled laborers.Footnote 7

Emerging trade diasporas during the early modern period were associated with trajectories both of internal migration and of external migration. For the merchants, apprentices, artisans, and laborers who comprised these trade diasporas, commercial networks and business opportunities were likely more important factors in choosing destinations than whether or not these destinations lay within or beyond the borders of China. Two emerging diasporic trajectories within China roughly followed the basins of China’s two most important rivers for trade. Beginning in the mid-Ming and lasting well into the Qing dynasty, one important trajectory was upstream along the Yangzi River, from east to west. In the Ming, an adage related that people from the middle Yangzi province Huguang (modern-day Hubei and Hunan) were “filling in” Sichuan province in the upper Yangzi. Likewise, many migrants from Jiangxi province, downstream from Huguang, came to dominate commerce in Huguang. After Sichuan suffered depopulation in the violent Ming–Qing transition, this western, upper Yangzi province attracted new waves of migrants, more from Huguang than from any other province. Even within Huguang, particular emigrant communities, most notably Macheng County, came to specialize in migration. Another east–west, upriver diasporic trajectory drew Cantonese migrants from Guangdong province’s Pearl River delta along the West River into Guangxi province. This pattern became evident in the sixteenth century, as Cantonese merchants benefitted from and in some case drove Ming state expansion and consolidation on the southwestern frontier. Here we shall focus on the three most prominent Chinese trade diasporas that were active in the sixteenth through early eighteenth centuries. Two of them were primarily active within the borders of the Ming and Qing empires, the third most notably overseas.Footnote 8

Map 1.1 Emigrant communities and destinations, c. 1600, with southern Fujian inset.

Shanxi Merchants

During the sixteenth century, merchants from the northern Chinese province of Shanxi likely formed the largest Chinese trade diaspora. Because their province was ideally situated between the most important Ming garrisons along the northern frontier and the economic heartland of China to the south, Shanxi merchants benefitted from Ming policies to supply the garrisons. In exchange for shipping grain and cloth to the northern frontier garrisons, merchants received licenses to trade in salt, a government monopoly. Shanxi merchants lost their geographical advantage when, a few years before the advent of the sixteenth century, the Ming state changed its border supply and salt monopoly policies. Now, the state sold salt licenses for silver, with which the state in turn purchased supplies for its northern garrisons. But this change also meant that Shanxi merchants could branch out from specializing in supplying the northern garrisons. Consequently, Shanxi merchants began to settle in cities in eastern China that were hubs in the salt distribution network. In particular, by the early sixteenth century Shanxi merchants had a large presence in the city of Yangzhou. Some Shanxi merchants moved into other trades and expanded the geographical range of their activities. In Chapter 2, we will return to the Shanxi merchants, following them as they expanded their trade far into Inner Asia in the wake of Qing imperial expansion. That Shanxi, particularly its southern prefectures, was home to one of the most important Chinese trade diasporas in Ming and Qing times belies the image that only natives of the southeastern coastal provinces of Fujian and Guangdong ventured far from home.Footnote 9

Huizhou Merchants

Over the course of the sixteenth century, a competing trade diaspora, comprised of merchants from Huizhou, a mountainous prefecture some 460 kilometers upstream from Yangzhou along the Yangzi River, eclipsed Shanxi merchants in the salt trade in Yangzhou and in the cities and towns of the Jiangnan region, broadly referring to the Yangzi River delta south of the river. Initially making money from the timber and tea trades based on the forests of their native prefecture, Huizhou merchants, especially those from the core Huizhou Prefecture counties of She and Xiuning, began to seek their fortunes outside the prefecture, and soon came to dominate the salt trade in many places. If we can take at face value the estimate of one sixteenth-century literatus, a large proportion of the Huizhou population lived and worked outside the prefecture. In an essay celebrating the fiftieth birthday of a Huizhou merchant who had traded in Yangzhou, Huguang, and Guangdong, the literatus claimed, “in general it is the Huizhou practice that thirty percent are in the county and seventy percent are [elsewhere] throughout the realm.” Writing in terse and thereby ambiguous prose, the literatus does not specify whether this proportion refers to the entire population of Huizhou or only to adult males. Based on this estimate, however, demographic historian Cao Shuji suggests that some 300,000 Huizhou natives worked as merchants outside the prefecture, and at least half of these 300,000 merchants eventually acquired formal household registration in Yangzhou and other places where they worked in the late Ming.Footnote 10

Let us meet two Huizhou merchants who spent at least part of their careers in Yangzhou during the sixteenth century. They appear in the collected writings, published in 1604, of a Xiuning County literatus. The author depicts one of these migrant merchants as wealthy and well-connected, the other as poor. The wealthy merchant was none other than the author’s father, who appears in the author’s writings not by name but by a prestige title in the Ming bureaucracy, the “gentleman of meritorious achievement.” That a merchant could claim such a title suggests the immense wealth that salt merchants could accumulate and their close connection to the state. We learn about him through biographies of three of the author’s four “mothers,” that is, the gentleman’s primary wife and his three secondary wives, or concubines. The gentleman’s accumulation of wives indicates growing prosperity and social connections. The primary wife, surnamed Cheng, and almost certainly a native of Huizhou, gave birth to the author’s older brother. The first concubine, Xie, a native of Huguang province, gave birth to the author in 1552. In the same year, a second concubine, Li, a native of Jiangbei, possibly referring to the region north of Yangzhou, gave birth to the author’s younger brother, and the gentleman’s third son. The gentleman acquired a third concubine, a teenage girl surnamed Feng, while working in the family salt trade in Yangzhou. Feng, a native of a town nearby to Yangzhou, would produce three more sons.Footnote 11

In contrast to the author’s father, at the lowest end of the socioeconomic ladder, a man would consider himself extremely lucky even to acquire a primary wife, let alone concubines. Nevertheless, the pattern of male migration as a family strategy for socioeconomic benefit was not unique to the wealthy.

The poor migrant Huizhou merchant, Wu Kun, was a distant member of the author’s lineage. The author depicts Wu Kun’s father, Wu Gang, as an itinerant merchant both fond of travel and pressed by poverty. In 1564, when Kun was about twenty years old, his father left home on one of his many journeys, this time to sell paper in Huguang and Shanxi. Because the author of this account was the son of a wealthy salt merchant who had four wives and six sons, we must be careful in judging what the author means when he depicts Wu Gang as driven by poverty. Wu Gang was wealthy enough to be accompanied on his distant travels by a family servant named Youfu. In any case, after several years, news from Wu Gang and his servant no longer reached their home in Xiuning. In the absence of his father’s financial support, the original aim of his distant travels, Wu Kun took over responsibility for caring for his mother and, in time, his own wife and children. He first sold wine, but then decided to learn commerce in Yangzhou, hoping that perhaps he might get word of his father’s whereabouts, although Yangzhou was in the opposite direction from Huguang and Shanxi. In 1572, Wu Kun heard from a lineage member of a possible sighting of his father near the border of Huguang and Sichuan. Over the next two decades, Wu Kun made three separate trips upriver to find his father. He eventually located his deceased father’s remains in eastern Sichuan province, and learned from a fellow Huizhou merchant based there that his father had died in 1574 while trying to make money selling cloth.Footnote 12

The author portrays the tale of Wu Kun’s father as a tragic one, and it is easy to imagine the loss that Wu Kun and his mother felt when they ceased to receive news and remittances from Wu Gang. The author also celebrates Wu Kun’s filial piety, exemplified by multiple treks to find his father during which he followed seemingly false leads, encountered famine, and feared for the health of his mother while he searched for her lost husband. The tale also illustrates the extent of a trade diaspora stretching out for over 1,000 kilometers from Yangzhou to Sichuan. Whether learning the ropes in Yangzhou or searching for his father’s remains in Sichuan, Wu Kun relied on the aid of fellow Huizhou migrants and Wu lineage members. As evidenced by the writings of our literatus author, a local culture of migration existed by 1604. The author praises his multiple mothers, native to Huizhou, Huguang, and Yangzhou, and the determination of the filial son Wu Kun. The prevalence of this strategy already had an impact on cultural production.

Hokkien Merchants

A third important early modern Chinese trade diaspora was that of the Hokkien, or southern Fujianese. Unlike merchants from the inland areas of Shanxi and Huizhou, Hokkien merchants were primarily maritime traders, operating both along the China coast and overseas. “Hokkien” refers primarily to speakers of the Hokkien dialect from two neighboring prefectures in southern Fujian province: Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. We have seen that by the fifteenth century some Hokkien communities were beginning to emerge at destinations in Southeast Asia. These communities would become much more substantial, stable, and well-documented during the early modern period.

The vicissitudes of the Hokkien overseas trade diaspora were closely related to fluctuations in maritime policy of the Ming state. In the middle decades of the sixteenth century, the southeastern coast of China experienced an upsurge in coastal raids by armed groups operating off its shores. Ming records refer to the attackers as wokou. Although this term literally means “Japanese pirates,” most of the raiders were in fact Chinese from communities along the southeastern coast. When Ming policy forbade outbound overseas trade, merchants involved in the trade became, in the state’s eyes, smugglers. And because both traders and smugglers often armed themselves for protection, it was a small step to turn from smuggling to pillaging other coastal communities.Footnote 13

With a new emperor on the throne, in 1567 the Ming state pursued a different policy by lifting the ban on private maritime trade, allowing it through a single port in Zhangzhou Prefecture. Originally known as Yuegang, or Moon Harbor, this port now received the new, state-endorsed name Haicheng, or Sea at Rest. The Ming state granted a limited number of licenses, initially fifty but growing to over a hundred by the end of the century, to private merchants to trade in Southeast Asia from Haicheng. The shift in Ming policy was largely the result of lobbying on the part of literati and officials from Fujian who understood the importance of overseas trade for their communities.Footnote 14

By the early seventeenth century, there were significant communities of Hokkien migrants at several overseas destinations, the closest of which was the island of Taiwan. Hokkien merchants traded with aboriginals in northern Taiwan, exchanging textiles and other Chinese goods for such Taiwanese products as venison and gold. Over the course of the seventeenth century, Hokkien traders and agricultural settlers were concentrated on the plains of Taiwan’s west coast, which faces Fujian across the Taiwan Strait. When Dutch colonizers arrived in this part of Taiwan in 1623, they found some 1,500 Chinese traders and settlers, almost all of whom were surely Hokkien. The Hokkien population grew significantly from the 1630s, when Dutch administrators encouraged Chinese migration to Taiwan. Hokkien merchants helped the Dutch monopoly trade company for Asia, the VOC (Dutch East India Company), build the Dutch colony on Taiwan, recruiting Hokkien laborers, a process that one historian has described as “co-colonization” of Taiwan, by both Dutch and Hokkien migrants. Hokkien settlement in Taiwan further increased after 1661, when the Dutch lost control of Taiwan to a network of Hokkien traders and pirates based at the southern Fujian port of Xiamen (Amoy) under the leadership of Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga). Migration further increased after 1684, when the Qing regime decided to incorporate Taiwan as a prefecture of Fujian province following Qing victory over the Zheng regime. By this time, Xiamen, in Quanzhou Prefecture’s Tongan County, near the border with Zhangzhou Prefecture, had superseded Haicheng as the most prominent port in southern Fujian.Footnote 15

Before 1684, the largest of the overseas Hokkien communities was probably in the Philippines, especially its main city, Manila. After the Spanish established a colony in the Philippines in 1571, Manila became the key link in the global exchange of Spanish American silver for Chinese manufactured goods. Spanish galleons carried the silver, acquired from mines in Spanish-controlled Peru and Mexico, to Manila. As many as thirty Hokkien junks, or ships, arrived annually in Manila laden with such products as silk and porcelain. Because of the seasonal nature of the Hokkien junk-Spanish galleon trade, the size of the Chinese community in Manila fluctuated; however, it far outnumbered the Spanish, who relied on Hokkien merchants to supply their colony with such necessities as cotton cloth and metal utensils. In 1603, for example, a Spanish observer estimated that there were some 20,000 Chinese (mostly Hokkien) in the Philippines compared to just a thousand Spaniards. Despite tensions culminating in a Spanish-led massacre of thousands of Chinese in 1603, and a massacre on a similar scale again in 1639, the Hokkien community in Manila soon recovered.Footnote 16

The overseas Hokkien trade diaspora included communities in several polities that were not European colonies. By the early seventeenth century, several hundred Hokkien traders were active in southwestern Japan. Some of them had relocated their operations to Japan after the 1603 massacre in the Philippines. The early Hokkien merchants in southwestern Japan included Zheng Chenggong’s father, who began to build his maritime empire there. In 1635, the Japanese Tokugawa regime (1600–1868) restricted Chinese trade to Nagasaki, where a significant Chinese community was already developing. As in other places, the Chinese population fluctuated seasonally, with the arrival and departure of trading junks, though a smaller permanent population of Chinese remained. When the junk fleets were in, the Chinese population approached 5,000 or more. Unlike Taiwan and Manila, where Hokkiens formed the overwhelming majority of the Chinese population, in Nagasaki Hokkiens competed and cooperated with Chinese migrants from northern Fujian and from the Jiangnan region.Footnote 17

Other Hokkien communities emerged along the coast of mainland Southeast Asia, including in the Nguyen regime in central Vietnam. Unlike northern Vietnam, which relied on an agrarian tax base, the Nguyen regime generated revenue by promoting, and ultimately taxing, international trade at its port city of Hoi An. In the mid-sixteenth century, when the Ming prohibited direct trade with the Japanese during the height of the wokou attacks, Hoi An offered a safe venue for the Chinese-Japanese trade, and substantial Chinese and Japanese communities began to emerge in the city. After the lifting of the Ming maritime ban in 1567, the Chinese community at Hoi An continued to prosper. By 1642, one European visitor estimated that there were some 5,000 Chinese in Hoi An. Unlike Nagasaki, the Chinese community at Hoi An was almost entirely Hokkien. Hokkiens also made up the majority of a growing Chinese community in Siam, where the Siamese kings in the capital, Ayutthaya, entrusted Chinese to run royal trading monopolies, including Siamese overseas trade with Japan. In the 1680s, a French diplomat estimated the Chinese population in Ayutthaya at between 3,000 and 4,000.Footnote 18

Most remote was the island of Java, where Chinese traders were already active before the sixteenth century. As in other locales, however, overseas Chinese communities appear much more clearly in the historical record from the sixteenth century. For example, a large number of Chinese were active at the port city of Banten, in the sixteenth century under the rule of a local sultan. After the Dutch established colonial rule at nearby Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) in 1619, a large Chinese, overwhelmingly Hokkien, community developed there. As with the Spanish colonial city of Manila, Hokkien merchants, artisans, and laborers built and supplied Dutch Batavia. The Chinese population of the walled city of Batavia fluctuated both with seasonal trade and with changing relative social and economic conditions in Batavia and other destinations on Java and nearby islands. Dutch counts of the Chinese population of Batavia show over 3,000 in 1648 and close to 3,700 in 1699. In 1739, a year before an outbreak of violence led to a massacre of Chinese known as the Batavian Fury (1740), the Dutch counted 4,199 Chinese in the walled city, compared to just 1,276 Europeans. Close to 10,000 Chinese resided in the countryside outside Batavia, where they ran plantations.Footnote 19

The emerging Hokkien diaspora in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries may be characterized as a trade diaspora in that it was driven by trade and, as socioeconomically complex as it was, its most prominent members were merchants. Migrants from two southern Fujian prefectures, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, targeted specific destinations in maritime Asia, ranging from Nagasaki to Batavia. Hokkien migrants pursued strategies both of specialization and diversification. Within Quanzhou and Zhangzhou prefectures, only particular towns, villages, and lineages sent migrants overseas. In general, prominent traders were more likely to come from Quanzhou, and agricultural settlers from Zhangzhou. Yet, as the historian Lucille Chia observes, members in successive generations of a single Zhangzhou lineage who all specialized in the cultivation of sugar cane and the production of sugar pursued this trade in destinations as diverse as Taiwan, the Philippines, and Batavia.Footnote 20

A large proportion of the tens of thousands of Hokkien migrants who left Fujian in the early modern era came from Longxi County, the seat of Zhangzhou Prefecture. Read together, a variety of Chinese-language historical sources – court records, gazetteers, genealogies, and tomb inscriptions – show the diverse but specific overseas destinations that Longxi migrants targeted between the fifteenth and early eighteenth centuries. Court records are a rare source that reveal traces of an emerging Longxi diaspora before the sixteenth century. The historian Pin-tsun Chang has discovered in Ming court records from the 1430s and 1440s requests by envoys on tribute missions from states on Java and from Siam for permission to visit Longxi County. The envoys claimed that they were of Chinese ethnic origins, and that they or their ancestors were Longxi County natives. They requested permission either to return permanently to Longxi or to visit temporarily in order to offer ritual sacrifices to their patrilineal ancestors.Footnote 21

Local histories, or “gazetteers,” of provinces, prefectures, and counties in China occasionally include information on migrants in the early modern period, but they typically contain more information on migrants’ family members who remained in the emigrant communities. A new edition of the gazetteer for Longxi County was compiled in 1762. As with most gazetteers, this one featured brief biographies of exemplary wives, that is, wives who remained loyal to their deceased husbands by refusing to remarry and in some cases committed suicide. The husbands of many such women included in the gazetteer were overseas migrants. For instance, when Chen Guoniang’s husband perished while trading overseas, we are told, her mother-in-law encouraged her to remarry, but Chen gently resisted and eventually won her mother-in-law’s acclaim. Similarly, when the husband of a woman surnamed Zhou died in Taiwan, Zhou strangled herself to death, an act for which she received state honors in 1751.Footnote 22

Historians of migration have used genealogies, both those produced in emigrant communities and those produced overseas, to trace migration. The demographic historian Wang Lianmao analyzed the 1774 genealogy of a Lin lineage based in a village not too far from the port of Haicheng in Longxi County. Almost all of the approximately 2,000 residents of the village in the late twentieth century belonged to the Lin lineage. Wang found that 336 Lins in the 1774 genealogy were listed as having died and been buried outside Longxi, many in Taiwan and Batavia. Emigration was evident early on, at an annual rate of 0.26 persons for the years 1520–1679. But levels jumped dramatically with the opening of the southeast coast following the Qing conquest and incorporation of Taiwan, with an average of three emigrants per year between 1680 and 1759. Even in the initial period, it is likely that most Lins in the village would have known someone who was overseas. In the latter period, migration had become a way of life for most families in the village.Footnote 23

Genealogies produced overseas offer a different perspective on migration, showing the fates of migrants’ descendants who settled abroad. The historian Chen Ching-ho (M. Chen Jinghe), a descendent of Zhangzhou migrants who settled Taiwan, located and published the genealogy of a Chen family from Longxi County that settled in central Vietnam, near the port of Hoi An. The genealogy, originally compiled in 1799 and updated in 1875 and 1930, shows how the first migrant and at least two generations of his descendants remained active both in Longxi and in Vietnam (Figure 1.1). The man who would become the migrant ancestor of this Chen (or Tran, in Vietnamese pronunciation) lineage was born in Longxi in 1610. The genealogy states that he “came south” as a refugee during the warfare that marked the Ming-Qing dynastic transition. The genealogy gives little information about this man’s first wife, other than that she was a subject of the Ming state, from which we can conclude that she was Chinese, and almost certainly more specifically Hokkien. The migrant ancestor married a “successor wife,” implying that the original wife had died; she was a native of Vietnam. After Chen died, in 1688, he was buried north of Hoi An. He was survived by two sons, the eldest borne by the first wife in China, the second by the Vietnamese wife. The eldest son, Chen Deshan, was born in 1644, a month after Qing forces captured the Ming capital, Beijing. The genealogy relates that Deshan, born in China, “stayed at the old native place to take care of his mother; over ten years later, he came south to seek his father,” which suggests that his father possibly married the Vietnamese woman before his Chinese wife died in Longxi. In Vietnam, Deshan married the daughter of another Chinese migrant. After Deshan and his wife both died during a plague in January, 1715, they were buried in central Vietnam’s Quang Tri Province. The eldest of Deshan’s five sons, Chen Zong, was born in Vietnam in 1675. After the birth of his own eldest son in 1699, the genealogy states, Zong “returned to his old state,” one he had never seen of course, “where he met with all of his lineage members in the ancestral hall, and lived together there with them for two years before coming back [south].” Upon his death in 1715, Zong was buried in Quang Tri. From this genealogical record, then, we can trace ways in which members of this family maintained links in both emigrant and host societies over three generations.Footnote 24

Figure 1.1 The Chen (Tran) family.

Court records, gazetteers, and genealogies, as well as the tomb inscriptions that opened this chapter, confirm that Longxi County provided a large number of the migrants who made up the growing Hokkien diaspora in early modern times. That migrants from this single county left such widespread traces in the historical record reminds us that Longxi migrants, like Hokkien migrants more generally, targeted specific destinations. Unlike the case with other Hokkien migrants, we find only a single trace of Longxi migrants in Japan, for example. But these records do hint at the prevalence of migration among some Longxi communities, and the presence of Longxi migrants overseas generally and specifically in Taiwan, central Vietnam, and Java. The materials suggest connections, or in some cases at least claims of connections, between Longxi and places overseas: envoys wanting to visit their ancestral home, families in Longxi altered by death of a migrant overseas, efforts of genealogists to include information on lineage members who never returned from overseas, the two-year residence of a migrant’s grandson born and raised in Vietnam, and assertions of Longxi County identity inscribed on tombs of Longxi migrants or their descendants in Cirebon.Footnote 25

Migrants from Longxi County of course comprised only a portion of the broader Hokkien trade diaspora that took shape in the early modern period. Likewise, the Hokkien diaspora was only one among several prominent trade diasporas – including Cantonese, Huizhou, and Shanxi – during this period. Because trade diasporas were comprised not only of merchants but also of boatman, porters, apprentices, artisans, and other personnel, these expanding trade diasporas created cultures of migration among specific communities in southern Fujian, the Pearl River delta, Huizhou Prefecture, and southern Shanxi.

Refugees, Military Adventurers, and Chinese Satrapies in Indochina

One distinct diasporic trajectory consisted of equally ambitious and desperate men who made their way to Southeast Asia during the Ming-Qing transition. Although the Manchu-led Qing forces captured Beijing quite readily in June, 1644, after the reigning Ming emperor committed suicide upon a rebel invasion of his capital two months earlier, it took another four decades for the Qing to eliminate various Ming loyalist regimes and fully to consolidate its control over southern China with the defeat of the Zheng regime on Taiwan. Many of the Chinese migrants who ended up in Japan and Southeast Asia during these tumultuous decades either embraced identities as subjects of the fallen Ming or were so classified by the overseas regimes in which they now resided. The genealogy of the Chen lineage in central Vietnam that claimed descent from a Longxi County migrant stressed that the migrant ancestor “maintained the Ming style of clothing” after settling in central Vietnam, in contrast to his China-born son, Deshan, who before leaving for Vietnam had already “changed to the Qing style of clothing.” Accordingly, scholarship on diasporic Chinese tends to depict the many Chinese who went abroad in the mid- and late seventeenth century as Ming refugees. No doubt, for many Ming loyalists the dynastic transition was a significant “push” factor in the decision to migrate.Footnote 26

Nevertheless, the term “refugee” does not fully capture the essence of many migrants who left China in the wake of the Ming collapse. In fact, such migrants, many of them armed to the teeth, could equally justifiably be described as military adventurers, some of whom established in Southeast Asian port cities powerful operations that came to resemble independent states. This phenomenon was not unique to the Ming-Qing transition. In the sixteenth century, and even earlier, some Chinese pirates, many of whom began as merchants or smugglers, established similar bases of operation in Southeast Asia. Most famously, in the 1560s or 1570s the Chinese pirate Lin Daoqian led some 2,000 followers, probably most of them Hokkien, from the Fujian coast to capture the port of Patani (Pattani), on the portion of the Malay Peninsula that is now a part of Thailand. Here he built a small state that derived its income from coastal trade. Given the overlap among trade, smuggling, and piracy, Lin’s followers could be considered part of the emerging Hokkien trade diaspora.Footnote 27

The Ming-Qing transition produced many migrants who, though often later described as “refugees,” were not all that different from Lin Daoqian’s pirates. Sponsored by various indigenous regimes on mainland Southeast Asia, they developed semi-independent satrapies in the lower Mekong delta, in what is now far southern Vietnam and Cambodia. In 1679 a group of 3,000 Chinese fighters, at least loosely connected to the Zheng regime on Taiwan, arrived in Hoi An aboard dozens of junks. Rulers of the Nguyen regime sent them to the Mekong delta, where they settled near the modern-day Ho Chi Minh City. Pushing into territory under a crumbling Khmer regime, these Chinese settlers essentially opened up the southern frontier for the expanding Nguyen regime. But the Chinese settlers enjoyed a great deal of control over their satrapies; one migrant leader, who settled the commercially booming Ban Lam (at present-day Bien Hoa), for example, was succeeded by his son when he died in 1715.Footnote 28

The most famous “refugee,” Mac Cuu (M. Mo Jiu), hailed from southwestern Guangdong, and thus was Cantonese broadly defined. Mac reputedly left Guangdong in 1671 for Cambodia, where he served the Khmer ruler as a commercial official in Phnom Penh, a city that already in the early seventeenth century had a community of some 3,000 Chinese. Two decades after settling in Cambodia, Mac moved to the southern port of Hatien, where he held a Khmer official title and ran a tax farm on gambling for the Khmer court. From 1708, Mac shifted allegiance to the southward expanding Nguyen regime, sending tribute to the Nguyen court and receiving an official title in return. Under his semi-independent rule, Hatien developed into an important port in maritime trade. When Mac Cuu died in 1735, his son succeeded him.Footnote 29

By the early eighteenth century, then, decades after the fall of the Ming, there existed a cluster of semi-independent Chinese-led regimes on the southern Indochinese peninsula. Nominally loyal to indigenous states in Vietnam and Cambodia, with leadership inherited within Chinese migrant families, during the early eighteenth century these regimes were tantamount to satrapies under the economic and military control of Chinese migrants.

Kinship, Native Place, and Ritual: Early Modern Chinese Diasporic Institutions

We may conceive of institutions that facilitated Chinese migration and shaped Chinese diasporic trajectories as diasporic institutions. Many such institutions were already in existence before the early modern period, but evolved into institutions that facilitated migration or organized migrant communities. Other institutions came of age during the early modern era as the trade diasporas described above took shape. Three important institutions that facilitated both internal and external migration during this period – lineages, native-place associations, and temples – were based on various combinations of kinship, native place, and ritual.

The lineage is sometimes referred to in English-language scholarship as “clan.” Among Han Chinese in the early modern era, lineages were patrilineal, that is, they were generally organized along lines of patrilineal descent from a focal male ancestor. Lineage practice was thus usually more salient for men than for women. For much of imperial Chinese history, lineage practice was more particularly reserved for aristocratic male elites. Beginning in the Ming dynasty and continuing into the Qing, however, lineage practice spread dramatically across socioeconomic classes. The increasingly rapid rate of lineage formation along the southeast coast from the sixteenth century coincided with the emergence of trade diasporas.

Different lineages in home communities might take contrasting stances toward lineage members who not only sojourned but actually settled in destinations far from the emigrant community in which the lineage was based. Some lineages expelled members who settled elsewhere and did not maintain contact with kin in the emigrant community, or were not wealthy enough to offer financial support to the lineage. Other lineages allowed migrants to retain rights to income from corporate property, that is, property owned by a lineage as a corporate unit to support lineage rituals. Powerful lineages with large holdings of corporate property, which mainly comprised agricultural lands but could also include timber stands in mountains and shops in cities and towns, were especially common in some of the places that served as home bases of trade diasporas, such as Huizhou Prefecture, southern Fujian, and the Pearl River delta. Increasingly from the sixteenth century, lineage halls, symbolizing the power of local lineages, were established and came to dominate the landscape in many emigrant villages and towns in Huizhou, Fujian, Guangdong, and elsewhere. Editors of the Longxi Lin genealogy analyzed by demographic historian Wang Lianmao clearly made efforts to include information about overseas migrants, even when they never returned to Longxi, as evidenced by records of their burial overseas.Footnote 30

In host societies, lineages, or more broadly patrilineal kinship, provided one common means of organizing immigrants. The genealogy of the Chen family that migrated between Longxi and central Vietnam represents an early effort to maintain this transnational family as a coherent ritual unit. Somewhat counterintuitively, the idea and practice of patrilineal kinship could be quite flexible. In host societies, people of the same surname, even if hailing from different emigrant communities, might use a claim of shared descent from a putative common ancestor who lived centuries in the past in order to organize themselves for a common purpose.

The native-place association was a Ming-era innovation. In Ming and Qing times, this type of institution was usually designated by the term huiguan. Although sometimes translated into English as “guild,” because membership in huiguan that served male travelers or sojourners was based on shared native-place origins, “native-place association” more accurately conveys the organizational logic behind this institution. The first huiguan emerged in Beijing during the early Ming as hostels and meeting places for candidates for the highest-level examination in the empire’s civil service examination system. Each huiguan would serve examinees from a particular native place, as large as a province or as small as a county. Around the turn of the seventeenth century, a new type of huiguan emerged, serving merchants rather than examinees. These new huiguan catered to the needs of merchants from particular provinces, prefectures, or counties doing business in trading or manufacturing centers away from home. Such huiguan became much more commonplace in the early eighteenth century. In the West River basin connecting the two southern provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, for example, at least four huiguan for Cantonese merchants were established between 1708 and 1726.Footnote 31

While during the early modern period, lineages became much more widespread and merchant huiguan first appeared, Chinese popular religious temples long pre-dated the formation of early modern trade diasporas. Nevertheless, in the early modern period particular temples became important organizations for migrants in host societies both within China and abroad. In some cases, migrants exported a temple cult from their home region, establishing a branch temple in destinations away from home. In other cases, migrants worshiped a deity important to the community in which they conducted business or settled, thereby marking either their acceptance by the local community or their appropriation of an efficacious local deity. Some temples enshrined multiple deities, both those exported from a home community and local deities, or perhaps a single, hybrid deity. Like huiguan, temples might become organizations that primarily catered to the needs of migrants, organizing the migrant community in a particular place. For example, from the 1620s, in Nagasaki three temples separately served different native-place constituencies of the Chinese community: Hokkien traders from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in southern Fujian, traders from the Fuzhou area in northern Fujian, and traders from the Jiangnan region, or, more specifically, what by the eighteenth century came to be known as Sanjiang, or the Three Jiang: Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Jiangxi provinces.Footnote 32

A comparison of two temples established in the mid-seventeenth century, one by the overseas Hokkien community in Southeast Asia and one by the upriver Cantonese community in Guangxi, can illustrate some ways in which temples became diasporic institutions. In the coastal port of Malacca, the largely Hokkien Chinese community founded a temple called Blue Clouds Pavilion (Qingyun ting), probably in 1673. The temple enshrined several deities, but primarily Guanyin, a female Buddhist deity with wide appeal. The temple both served as a kind of administrative center for leaders of the Hokkien community and performed some of the functions of a Hokkien huiguan. In the riverine port of Dawu, the largely Cantonese community established a temple known as the Arrayed Sages Temple (Liesheng gong). A 1722 commemorative inscription claims that the temple was established over eighty years earlier, thus around 1640. This temple enshrined ten deities (the “Arrayed Sages”), but the central deity, the Northern Emperor, was particularly popular in the Pearl River delta and most likely brought to Dawu by Cantonese merchants. The author of the 1722 essay asserts that the deity made no distinction between Guangxi locals and Cantonese sojourners (ke) at Dawu, but admits that the Cantonese migrants “see the temple as their home”; tellingly, over 600 Cantonese, but just a few dozen locals, donated for the 1722 renovation of the temple.

Merchant patrons of both temples convinced literati, holders of civil-examination degrees, back home to write laudatory essays, and then had these essays inscribed on stelae, or stone inscriptions, which they prominently displayed at the temples. The author of a 1707 stele praised the virtues Zeng Qilu, a native of Xiamen and, when the essay was written, the preeminent leader of Blue Clouds Pavilion. The author held the highest civil service examination degree and was a native of Tongan County, which included Xiamen. He explains that he writes the essay in response to the request of a sojourner (ke) who had returned from Malacca, and told of Zeng’s accomplishments. The author of the 1722 essay for the Arrayed Sages Temple stele was a native of Nanhai County in the Pearl River delta who had earned the highest civil service examination degree just the year before. He explains that a fellow Cantonese who had “returned east” requested that he write this essay. Both authors probably got paid for their work, but shared native-place ties between the merchant patrons of temples far away and the high-ranking literati back home facilitated the merchants’ mobilization of their literati compatriots as writers and as sources of prestige.Footnote 33

Intermediaries and Quarters: Institutions for Managing Cross-Cultural Trade

Lineages, huiguan, and temples helped organize communities of Chinese migrants during the early modern period. Other institutions, such as officially designated intermediaries, facilitated interactions between Chinese migrants and various states that ruled territories in which they sought to make a living. Such institutions supported the emerging trade diasporas by facilitating the cross-cultural trade upon which these diasporas thrived.

We have seen that Mac Cuu and other military adventurers received official titles from the Nguyen and Khmer regimes in Vietnam and Cambodia. This was more likely to occur in territories that lay on the expanding frontiers only under the loose control of such states. In overseas Chinese communities located in territories more tightly controlled by indigenous regimes, those regimes often created institutions that designated particular leaders as headmen of the Chinese communities, to interface between Chinese migrants and indigenous residents, maintain order, channel grievances, and expedite the collection of customs duties and other commercial taxes. The selection of headmen sometimes went hand in hand with the designation of particular quarters of a city in which Chinese migrants were supposed to reside.

In Nagasaki, as early as 1604 the Tokugawa regime selected from among the Chinese trading there one man to serve as Chinese interpreter. Over time, this position tended to pass down among patrilineal or marriage relatives. By the end of the seventeenth century, all new Chinese arrivals had to reside in a designated Chinese quarter, the “Chinese enclosure” (Tōjin yashiki) (Figure 1.2). Among the Chinese resident there, Tokugawa authorities recognized three groups, each represented by junk captains and wealthy merchants, based on native place origin: southern Fujian, the Fuzhou area, and Sanjiang. Likewise, in Manila, by the end of the sixteenth century Spanish colonial authorities required that Chinese migrants who had not converted to Catholicism reside in a quarter known as the Parián. Although the precise location of this Chinese quarter within Manila changed over time, the principle of segregating unconverted Chinese remained throughout the early modern period.Footnote 34

Figure 1.2 An early nineteenth-century image of the walled Chinese enclosure, Nagasaki. Detail of Kan-Yō Nagasaki kyoryū zukan.

Ayutthaya, capital of the Siamese kingdom, hosted a large population of sojourners from other states. They were organized into foreign settlements, each in a designated area of the city. Chinese constituted one of the two privileged groups allowed to reside within the walled city of the capital. Each foreign settlement could choose its own leader, known in Thai as nai or amphoe, who played the dual role of leader of a foreign settlement and administrator in the Siamese bureaucracy.Footnote 35

The Dutch, with the largest European colonial regime in Southeast Asia during the seventeenth century, adopted a similar system of appointing headmen of ethnic communities in port cities under their rule. Under Dutch colonial rule, these headmen held one of a number of ranks, the highest being kapitan (captain). The earliest Dutch-appointed Chinese kapitans were at Batavia, home base of the Dutch monopoly trading company, the VOC. The first kapitan at Batavia, appointed at the very establishment of Dutch rule, in 1619, was a Tongan County man named Su Minggang (Bencon) who held the position for thirteen years. Surprisingly, the fourth kapitan, listed on a 1791 wooden tablet under her husband’s surname, was a woman who in the mid-seventeenth century succeeded her husband as kapitan upon his death and served for over eight years. The Chinese community in Batavia that these kapitans represented was intermingled with the Dutch population, rather than confined to a particular quarter as in Manila. In Malacca, a Dutch colony after 1644, the Chinese kapitans led the Chinese community through the Blue Clouds Pavilion. We have already met the first such kapitan, Longxi County native Zheng Fangyang. Upon Zheng’s death in 1677, Li Weijing, a native of Xiamen, succeeded him. The fourth kapitan of Malacca was Zeng Qilu, subject of the 1707 laudatory essay described above, a fellow Xiamen native, and Li Weijing’s son-in-law. Thus the Chinese kapitans of Malacca, and probably most members of the Chinese community there, were Hokkiens with a tight-knit leadership network.Footnote 36

In the locales where diasporic Hokkien merchants were involved in cross-cultural trade, it was common for indigenous and colonial rulers to adopt a system of recognizing leaders of the Chinese, usually Hokkien, communities. Under various titles, the headmen of Chinese migrant communities tended to be commercial elites tasked both with organizing the Chinese community and with interacting with the rulers of states in which they resided. In some places, such as Nagasaki, Manila, and Ayutthaya, rulers of such states designated particular urban quarters in which the Chinese were supposed to reside. The extent to which such segregation succeeded over time varied. The Tokugawa authorities in Nagasaki were perhaps most successful in this regard. In other locales, through trade, intermarriage, and secondary migration, substantial communities of ethnic Chinese, or ethnically mixed Chinese and indigenous peoples, emerged well beyond the confines of such quarters. For example, a Dutch doctor working for the VOC who visited Siam in 1654 noted the presence of Chinese in several towns along the Chao Phraya River between the coast and Ayutthaya; in one of these towns, he observed that the Chinese made their living by dying cloth. Similarly, Chinese pioneers developed sugar cultivation and other forms of agriculture in the hinterland of Batavia. Thus, the concept of “trade diaspora” can give the misleading impression that Chinese in early modern Southeast Asia resided exclusively in urban areas.Footnote 37

Male Migration, Split Families, and Intermarriage

One may also conceive of the family as an institution that facilitated migration. By the early modern era, many families operated as split families, that is, families that continued to function as economic and ritual units but had family members geographically dispersed across two or more places of residence. In this period, family members working or residing away from the family’s base were almost always males.

At the top of the socioeconomic ladder were scholar-officials and wealthy merchants. Elite men, variously described in English as scholar-officials, gentry, or literati, were highly geographically mobile as examinees in the civil service examinations, which took them to increasingly more competitive examinations at county and prefectural seats, provincial capitals, and the imperial capital, Beijing. Successful examinees might then serve as officials assigned throughout the empire. Near the top of the ladder were wealthy merchants such as the Yangzhou salt merchants, most of whom were members of the Huizhou diaspora. Yet male migration as a family strategy for socioeconomic advancement, maintenance, or simply survival was common across the social spectrum, moving in roughly decreasing socioeconomic standing from long-distance traders, to shop owners and apprentices, to artisans, to itinerant peddlers, to manual laborers, to beggars. Income from any of these professions could help sustain the family as an economic unit. Recent work on military conscription in the Ming has demonstrated that this system gave incentives to families registered with the state as military households to maintain links with male family members serving in garrisons far removed from home. The export of male labor reinforced a gendered division of labor, with adult males earning money away from home and women fulfilling a range of productive, reproductive, and managerial tasks at home. One historian has stated that “the economic system” in Ming-Qing China “was built around male migration and female domestic labor.”Footnote 38

Because of the strong links that many male migrants maintained with their families, scholars of overseas Chinese migration have drawn an analytical distinction between two types of migration, sojourning and settling. As applied to early modern Chinese migration, sojourning refers to migrants, usually male, who spent significant time away from home, perhaps years or even decades, with the intent of returning home eventually. This concept helps us to see the native-place and family links between migrants and their home communities. Settling, or “migration” narrowly defined, refers to migrants taking up permanent residence in a migration destination, or host society. Within China, settling entailed the possible acquisition of household registration in the new community; if abroad, it meant perhaps achieving some status as subjects or citizens of the host state. The distinction between sojourning and settling can be a useful one, but it should not be overdrawn, since many sojourners ended up settling and some settlers, or their descendants, might in fact return to an emigrant community. Moreover, a male family member “sojourning” in a destination for years, and acquiring property there, might eventually bring other family members to take up permanent residence, that is, individual sojourning might lead to family settlement. Thus, male migration as a family strategy often flexibly combined a sojourning or labor-export strategy, sustaining a family back home through remittances, with a settling strategy, paving the way for a family’s permanent migration.Footnote 39

“Both the labor-export and family migration strategies,” historian Philip Kuhn observed, “belie the traditional image of China as a nation of stay-at-homes.” Many educated Chinese encountered this conventional image in classical texts that formed the subject of the civil service examinations. One oft-quoted phrase appears in the Analects (Lunyu), in which the sage Confucius states, “While his parents are alive, [the son] may not go abroad to a distance.” Of course, the people for whom such texts were most meaningful, the men who traveled to a distance in order to take civil service examinations and fill bureaucratic posts, were arguably the most mobile class of people in imperial China. Accordingly, both class and gender biases undergirded social expectations of geographical mobility. If scholar-officials recycled such strictures with greater frequency in early modern times, it was likely because men and women from other social classes were attaining unprecedented levels of geographical mobility that seemed to threaten existing social and gender hierarchies.Footnote 40

With the increased prevalence of migration as a family strategy, concepts such as native place became more salient and the task of maintaining family stability and gender hierarchy became more urgent. In particular, migrant men placed greater emphasis on women, especially wives, as anchors of the split family. Historian Guo Qitao has shown that the cult of female chastity became especially important in Huizhou during the Ming and Qing largely because the adult males of so many Huizhou families lived and worked as merchants outside the prefecture. Thus, whereas women left at home might acquire new roles as managers of household economies, the practice of male migration and the ideal of female chastity reinforced patriarchy. Similar dynamics existed in the homeland of the overseas Hokkien diaspora. From the late Ming and into the Qing, celebratory biographies of loyal wives of overseas migrants can be found in southern Fujian gazetteers. We have seen two such biographies from the 1762 gazetteer of Longxi County, in Zhangzhou Prefecture. Two earlier examples come from the 1612 gazetteer of Quanzhou Prefecture. On one page in the chapter devoted to chaste wives are biographies of two women from the same rural district in Jinjiang County. Both of their husbands died as sojourners in Luzon, the island in the Philippines where Manila was located and where most Hokkien migrants were concentrated. Despite the best efforts of in-laws and parents to prevent it, each woman eventually strangled herself to death. Suicide was an extreme act; conceivably the deceased husbands would have preferred that their wives instead refuse to remarry, care for the husbands’ parents, and adopt male heirs to continue the husbands’ patrilines. Some such women also earned biographies in local gazetteers. But stories of wives insuring chastity through suicide perhaps comforted other potential male migrants with the notion that their wives would remain steadfastly loyal while they sought their fortunes overseas.Footnote 41

No comparable cult of male chastity existed. On the contrary, male migrants pursued a range of economic and sexual relationships with women, and in some cases men, in the destinations to which they migrated. In Yangzhou, a city dominated by sojourning male merchants from Shanxi and especially from Huizhou, a pervasive sex market emerged by the sixteenth century. In Nagasaki, even after construction of a designated Chinese quarter in 1689, resident Chinese merchants could hire Japanese prostitutes, whom Tokugawa authorities allowed to enter the Chinese quarter on business calls.Footnote 42

In Manila, Spanish colonial authorities in 1599 issued an ordinance targeting economic and sexual practices of migrant Chinese men. Authors of the ordinance were particularly concerned about homosexual relations between men from China and boys from among the indigenous population of the Philippines, the indios, an act for which they reserved the punishment of burning alive. Another problem they identified was sexual relations between Chinese men and indigenous women, for which the men would receive the reduced punishment of 200 lashes and ten years rowing on Spanish galleys. Although one must be careful when using laws to draw conclusions about social practices, it is clear that many of the more successful Chinese migrant men in the Philippines either married indio women or had more informal alliances with them. By the eighteenth century, a significant mixed Chinese-indio mestizo population emerged in the Philippines.Footnote 43

Intermarriage between overseas Hokkien migrant men and local women was also prevalent elsewhere. Zheng Chenggong, for example, was born to the Japanese wife of his father, who traded in southwestern Japan in the 1620s. And we have seen that the first member of the Chen family from Longxi County to migrate to central Vietnam married a Vietnamese woman, possibly even before his first wife back in Longxi died. During the eighteenth century, in Taiwan, as on other frontiers of the Qing empire where there was a shortage of Han Chinese women, migrant Han Chinese men frequently intermarried with indigenous women. In Batavia and other parts of the Indonesian archipelago, there emerged by the eighteenth century a population of mixed Chinese-local offspring that would come to be known as Peranakan. These overseas wives might be primary wives, and thereby indicate that the Hokkien male migrant was settling abroad. In other cases, in the view of the male migrant, or of his patrilineal lineage back in China, the indigenous wife was a concubine. In such cases, the gender dynamics of the split family changed, now with two women anchoring opposite poles of the family between which the male migrant moved.Footnote 44

Evolving Diasporic Communities: Two Brothers in Yangzhou

One day in the autumn of 1731, toward the end of the early modern period, five men toured one of the many gardens near the city of Yangzhou and recorded their outing in matching poems based on the rhyme scheme of a sixth-century poem. We know about this outing because one of the 1731 poems is preserved in the published poetry of one of the participants, Ma Yuelu. This idyllic gathering of urban literati was typical in the Jiangnan region; however, in Yangzhou, on the northern periphery of Jiangnan, the urban elite was made up almost entirely of Huizhou migrants and their descendants. Two of the participants were Ma Yuelu and his older brother, Ma Yueguan, whose grandfather had moved from Huizhou to establish himself in the salt trade at Yangzhou. Another participant, Wang Xun, also had Huizhou (Xiuning, to be precise) roots and at some point married the Ma brothers’ younger sister. The other two participants were literati from the city of Hangzhou, on the southern edge of the Jiangnan region; one was a kind of in-house literatus, the other an eminent and frequent guest.Footnote 45

As we have seen with the 1604 writings of the Xiuning County literatus, by the time that Ma Yuelu wrote his poem about the 1731 outing the Huizhou diaspora had long had an important presence in urban Yangzhou. In 1604, local observers claimed, perhaps exaggeratedly, that emigrants and their descendants in Yangzhou outnumbered Yangzhou natives twenty to one. By 1731, the Huizhou diaspora, atop which the Ma brothers sat as head merchants in the salt trade, transformed the city of Yangzhou. The urban male elite of this city was almost entirely made up of men, like the Ma brothers, who though born and raised in Yangzhou were still identified as Huizhou men. The Ma brothers had their own garden, family monastery, and library, the latter boasting the largest collection in the city. With these resources, the Ma brothers attracted literati from Hangzhou and positioned themselves as philanthropists and patrons of scholarship, literature, and art. They financed the 1734 establishment of what would soon become a prestigious academy, primarily serving students from Huizhou salt merchant families in Yangzhou.Footnote 46

The Ma brothers and other Huizhou salt merchants at the apex of Yangzhou elite society developed a close working relationship with the Qing state. They already occupied a privileged position as head merchants in the salt trade, a state monopoly. As arguably the wealthiest subjects of the Qing empire, salt merchants such as the Ma brothers by the 1730s increasingly became a source of funding for the court. They made “donations” to the imperial privy purse, separate from tax revenue collected by the formal Qing bureaucracy. Through such contributions, the salt merchants essentially paid extra taxes, but also protected their dominant position in the lucrative salt trade. As the Ma brothers and other salt merchants became more prominent in ensuing decades, they would further cultivate their relationship with the Qianlong emperor, a relationship that was advanced when the emperor visited Yangzhou on his southern tours.Footnote 47

As we have seen, the formation of the Huizhou trade diaspora in Yangzhou spurred the development of a thriving sex and marriage market in the city. Yangzhou was famous for its market in women, typically natives of the area around Yangzhou the most famous of whom were trained as high-ranking courtesans or as “thin horses,” women to be sold as concubines, or secondary wives. The highest-ranking women were courtesans, prostitutes trained in the literati arts, from such Jiangnan cities as Suzhou. Women from the region north of the Yangzi River and especially from north of Yangzhou, later known as Subei, occupied a lower niche. Nevertheless, the evolving diasporic community pulled these women in to the Yangzhou human-trafficking marketplace.Footnote 48

At the close of the early modern period, an evolving diasporic community had transformed the city of Yangzhou. The upper crust of the Huizhou trade diaspora, exemplified by the Ma brothers, constituted the urban elite. Such men cultivated close relationships both with Chinese literati from Jiangnan cities to the south and with Manchu emperors in Beijing to the north. They also drove a market in women; even while valorizing chaste wives and mothers in Huizhou, they patronized Jiangnan courtesans and purchased local concubines. Yangzhou was no doubt unique in many ways. Nonetheless, the dynamics of this evolving diasporic community resonated with those of Hokkien diasporic communities outside China, in such places as Ayutthaya. In both cities, a diasporic mercantile elite cultivated close relationships with the state that ruled these cities, carved out for themselves a prominent position in local society, and radically reshaped the local marriage market.