Introduction

Engagement in advance care planning (ACP) – which includes completion of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, living wills, and health-care proxy forms as well as having end-of-life (EOL) care conversations with family and providers – is associated with better quality of life at the EOL (Garrido et al. Reference Garrido, Balboni and Maciejewski2015) and receipt of care consistent with patients’ values (Detering et al. Reference Detering, Hancock and Reade2010). Patients with advanced cancer who have an accurate understanding of their prognosis are more likely to engage in ACP (Waite et al. Reference Waite, Federman and McCarthy2013), prefer comfort care over aggressive care (Weeks et al. Reference Weeks, Cook and O’Day1998), and receive goal-concordant care (Detering et al. Reference Detering, Hancock and Reade2010; Mack et al. Reference Mack, Weeks and Wright2010; Seale et al. Reference Seale, Addington-Hall and McCarthy1997). These patients are also less likely to receive futile aggressive EOL care (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Viola and Maciejewski2023; Seale et al. Reference Seale, Addington-Hall and McCarthy1997; Trice et al. Reference Trice, Prigerson and Trice2009; Weissman et al. Reference Weissman, Reich and Prigerson2021), a notable relationship given robust evidence that aggressive EOL care does not increase survival (Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Bao and Shah2015) but is associated with poor patient quality of life (Mack et al. Reference Mack, Weeks and Wright2010; Prigerson et al. Reference Prigerson, Bao and Shah2015) and caregiver bereavement adjustment (Garrido and Prigerson Reference Garrido and Prigerson2014; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Zhang and Ray2008). Despite the importance of prognostic understanding and engagement in ACP, less than half of patients with advanced cancer recognize they are terminally ill (Trevino et al. Reference Trevino, Zhang and Shen2016; Yun et al. Reference Yun, Kwon and Lee2010), have EOL care conversations (Garrido et al. Reference Garrido, Harrington and Prigerson2014; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Zhang and Ray2008), or complete advance directives (Dow et al. Reference Dow, Matsuyama and Ramakrishnan2010) (i.e., engage in ACP).

The problem of poor prognostic understanding and low engagement in ACP is common among underserved racial and ethnic groups. Only 11% of Latino patients with a prognosis of 6 months or less described themselves as terminally ill, compared to 39% of White patients (Smith et al. Reference Smith, McCarthy and Paulk2008). Similarly, only 12.9% of Black patients with a life expectancy of 6 months or less estimated their life expectancy within 12 months of their actual survival compared to 43.43% of White patients (Trevino et al. Reference Trevino, Zhang and Shen2016). Compared to White patients, Black and Latino patients are also more likely to have misconceptions about ACP (Jonnalagadda et al. Reference Jonnalagadda, Lin and Nelson2012), less likely to complete advance directives (Carr Reference Carr2011; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Henderson and Hyer2021; LoPresti et al. Reference LoPresti, Dement and Gold2016), and more likely to receive aggressive care at the EOL (LoPresti et al. Reference LoPresti, Dement and Gold2016; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Walsh and Horswell2021; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Rajan and Zhang2017). Despite these disparities, few interventions to improve prognostic understanding and engagement in ACP among racial and ethnic minority populations have been developed and tested (Teal and Street Reference Teal and Street2009).

Caregivers are a potentially strong yet overlooked target for intervention to improve ACP among racial and ethnic minority patients. Caregivers play an integral role in patients’ care and decision-making (Sudore and Fried Reference Sudore and Fried2010; Winzelberg et al. Reference Winzelberg, Hanson and Tulsky2005), especially among racial and ethnic minority patients for whom family and community members often actively participate in medical decision-making (Mead et al. Reference Mead, Doorenbos and Javid2013). When patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers have an accurate understanding of the patient’s prognosis, patients are more likely to complete advance directives (e.g., health-care proxy, living will, DNR order) and prefer comfort care over aggressive care than when 1 or both dyad members have an inaccurate prognostic understanding (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Trevino and Prigerson2018; Trevino et al. Reference Trevino, Prigerson and Shen2019). Further, dyadic prognostic understanding predicts advance directive completion beyond individual patient and caregiver prognostic understanding (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Trevino and Prigerson2018). These findings highlight the importance of ensuring both patients and their caregivers understand the patient’s prognosis accurately. Yet, in less than one-third of dyads, both the patient and caregiver accurately understand the patient’s prognosis (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Trevino and Prigerson2018; Trevino et al. Reference Trevino, Prigerson and Shen2019).

Barriers to having a shared prognostic understanding between patients and caregivers include inadequate communication skills within the dyad and the influence of distress associated with discussing prognosis (Chekryn Reference Chekryn1984; Kirchhoff et al. Reference Kirchhoff, Hammes and Kehl2010). Nearly two-thirds (65%) of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer report experiencing challenges communicating with the patient, particularly about emotionally distressing topics such as fears of treatment futility (Zhang and Siminoff Reference Zhang and Siminoff2003). These communication problems are associated with higher caregiver burden (Fried et al. Reference Fried, Bradley and O’Leary2005). Patients also endorse communication concerns, specifically that discussing ACP will damage their relationship with their caregiver (Schickedanz et al. Reference Schickedanz, Schillinger and Landefeld2009). Further, the emotional distress associated with these topics exacerbates avoidance of conversations about prognosis (Baik and Adams Reference Baik and Adams2011; Manne et al. Reference Manne, Dougherty and Veach1999; Zhang and Siminoff Reference Zhang and Siminoff2003) and likely contributes to patient–caregiver disagreement about the patient’s prognosis (Zhang and Siminoff Reference Zhang and Siminoff2003). Despite these factors and a clear need to help patients and caregivers discuss prognosis and ACP, few interventions around ACP and prognostic understanding exist that target the poor communication and distress dyads face.

The purpose of this pilot study is to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and pre-post impact of a communication intervention (Talking About Cancer [TAC]) on prognostic understanding, engagement in ACP, and completion of advance directives among a diverse, urban sample of patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. We hypothesized that the intervention would be feasible and acceptable to patients and caregivers. In addition, we hypothesized that the intervention would be associated with an improvement in prognostic understanding, engagement in ACP, and completion of advance directives.

Methods

Participants and procedures

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating sites. All participants provided informed consent. Patient–caregiver dyads were recruited from June 2020 to March 2022 (Note: All dyads except for n = 1 were recruited by June 2021. The final dyad was recruited in March 2022 due to unexpected internal delays at 1 of the sites due to staffing shortages and planned reductions in recruitment efforts as the conclusion of funding approached.) from 2 Northeast academic medical centers in an urban setting. Participants were identified through referrals from oncology providers and medical chart reviews by study staff. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of advanced cancer defined as follows: (1) locally advanced or metastatic cancer and/or (2) disease progression following at least first-line treatment. Additionally, eligible participants were aged 18 years or older, able to provide informed consent, able to identify a caregiver willing and able to participate in the study, fluent in English or Spanish, scored ≤10 on the Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test or scored <6 on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer1975), and able to communicate over the telephone. Caregivers were identified by the patient and defined as an unpaid individual who provides the patient with emotional, physical, and/or practical support. Eligible patients were also required to have had a discussion of prognosis with their oncologist to ensure they had the opportunity to understand their prognosis. Before patient enrollment, oncologists were asked whether they discussed any of the following with the patient: whether the cancer is curable, whether the cancer is terminal, or the patient’s life expectancy. Patients whose oncologist reported discussing at least 1 of these topics with the patient were eligible to participate. Patients were excluded if they were too weak to complete study procedures, receiving hospice care at the time of study enrollment, currently being treated for schizophrenia, substance use or dependence, and/or bipolar disorder, or deemed inappropriate for the study by their treating oncologist.

Eligible caregivers were aged 18 years or older, fluent in English or Spanish, deemed to be cognitively capable of engaging in study procedures by study staff, and able to communicate over the telephone. Caregivers were excluded if they were too weak to complete study procedures or currently being treated for schizophrenia, substance use or dependence, and/or bipolar disorder.

Finally, dyads were excluded if both members endorsed an accurate understanding of the patient’s illness as terminal with a prognosis of less than a year as prognostic understanding was the primary target of the intervention. We did this because the core content of TAC was focused on improving the accuracy of prognostic understanding. Patients and caregivers completed study measures administered by study staff over the telephone before starting the intervention and within approximately a week of completing the intervention. Patients and caregivers completed all measures separately and were compensated $25 for completing baseline assessments and $35 for completing follow-up assessments.

Intervention: Talking about Cancer (TAC)

The TAC intervention was informed by inhibitory learning theory (Blakey and Abramowitz Reference Blakey and Abramowitz2016; Craske et al. Reference Craske, Kircanski and Zelikowsky2008) and the cognitive-social processing theory of communication (Baik and Adams Reference Baik and Adams2011; Cordova et al. Reference Cordova, Cunningham and Carlson2001). These theories state that the anticipation of a negative outcome (e.g., partner distress), desire to protect others, and negative responses from others (e.g., criticism, invalidation) lead to avoidance of stressful events such as conversations about prognosis and poor processing of distressing cancer-related information. TAC reduces this avoidance by teaching patients and caregivers to express and manage their emotions while engaging in stressful conversations, thus promoting their ability to support each other during these conversations, (Baik and Adams Reference Baik and Adams2011; Blakey and Abramowitz Reference Blakey and Abramowitz2016; Bouton Reference Bouton2004; Manne et al. Reference Manne, Ostroff and Winkel2005; Scott et al. Reference Scott, Halford and Ward2004; Shields and Rousseau Reference Shields and Rousseau2004). The final version of TAC was informed by stakeholder feedback from patients, caregivers, and providers.

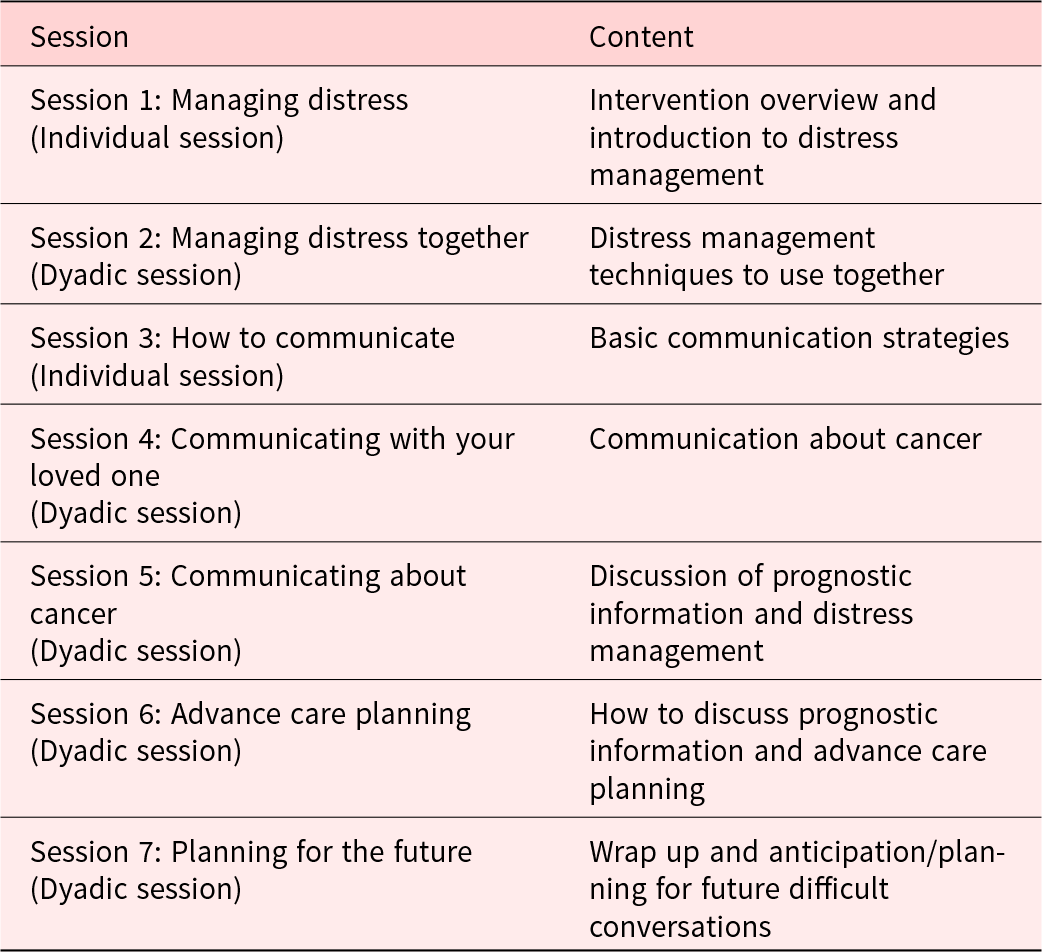

TAC is a 7-session weekly psychotherapy intervention delivered over the telephone by licensed social workers (see Table 1 for list of session topics) (In the current study, a total of n = 2 social workers delivered the intervention. All interventionists were informed patients had advanced cancer and poor prognosis.). Each session is 45–60 minutes in length. Session topics include the following: (a) Distress management strategies (Sessions 1 and 2) were informed by cognitive-behavioral therapy (Greer et al. Reference Greer, Traeger and Bemis2012) and coping interventions (Manne et al. Reference Manne, Rubin and Edelson2007, Reference Manne, Virtue and Ozga2017) effective in patients with cancer and include deep breathing and relaxation strategies and cognitive restructuring techniques (Freeman Reference Freeman2004). (b) Communication skills (Sessions 3 and 4) were informed by Gottman’s recommendations for couple communication (Gottman et al. Reference Gottman, Notarius and Gonso1976) and best practices for communicating in medical contexts (Brown and Bylund Reference Brown and Bylund2008) which highlight the skills of acknowledgment, validation, expressing empathy, asking open-ended questions, and verbalizing one’s feelings with “I” statements (e.g., “When we talk about your treatment not working, I feel worried.”). (c) Guided review of prognostic information (Sessions 5 and 6) was conducted using the distress management and communication skills reviewed in prior sessions to facilitate discussion of patients’ and caregivers’ interpretation of prognostic information previously provided by the patients’ oncologist. (d) Advance care planning (Session 6) information is provided and previously learned communication skills are used to help patients identify their treatment preferences and communicate those preferences to loved ones and the medical team. (e) Intervention review and future planning (Session 7). The final session consists of a review of topics covered in the intervention and development of a plan for managing future difficult conversations.

Table 1. Talking about Cancer (TAC) session content

Sessions 1 and 3 are conducted individually to provide the patient and caregiver with the opportunity to discuss their distress and communication strategies privately. All other sessions are conducted with the dyad to promote communication, coping, and engagement in ACP. The interventionist does not share information discussed in individual sessions with the dyad without permission from the patient or caregiver.

Measures

Demographic and disease characteristics

Patients reported their age, gender (male/female), race (White, Black, Asian, other), ethnicity (Latino vs non-Latino), education (college degree or less/post-graduate), income (<$21,000/≥$21,000), employment (yes/no), insurance coverage (yes/no), parental status (children/no children), partner status (partnered/other), and patient–caregiver relationship type (e.g., spouse, parent/child). Disease characteristics were extracted from the medical record and included cancer type, stage, presence of metastasis, and treatments. Performance status was also extracted from the medical record and assessed with the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) (Conill et al. Reference Conill, Verger and Salamero1990; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Bandukwala and Burman2010) and/or Karnofsky performance status (Karnofsky Reference Karnofsky1968).

Feasibility, acceptability, and treatment fidelity

Intervention feasibility was assessed with accrual and attrition rates as well as intervention session completion rates. Feasibility was defined as ≥70% of eligible dyads enrolling in the study (Badr et al. Reference Badr, Smith and Goldstein2015) and ≥70% of dyads who enrolled in the study completing a majority of the sessions (i.e., 60%, which is 4 of the 7 intervention sessions).

Acceptability was assessed post-intervention. Patients and caregivers rated the overall perceived helpfulness of the intervention. This item was rated on a 5-point scale from “not at all helpful” (1) to “very helpful” (5). Patients and caregivers also completed multiple-choice questions assessing the acceptability of the number of TAC sessions, session frequency, and the amount of information in the intervention. Acceptability was defined as ≥70% of patients and caregivers scoring ≥4 on the 5-point Likert scale items. Finally, patients and caregivers rated intervention difficulty (“How difficult was it for you to understand the content of the intervention?”; 1 = not at all, 5 = very much) and overall satisfaction with the intervention delivery (“Did you like participating in the intervention over the telephone?”: yes/no).

Treatment fidelity was assessed with a checklist that captured whether (1) core session content was delivered by study interventionists and (2) appropriate therapeutic techniques (e.g., shows positive regard, uses active listening skills) were used. These checklists were completed for a randomly selected 15% of intervention sessions by trained fidelity raters who listened to audio recordings intervention sessions. Fidelity was defined as delivering ≥70% of intervention components and using ≥70% of the therapeutic techniques.

Prognostic understanding was assessed at baseline and 1 week post-intervention with items used previously in studies of patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers (Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Prigerson and O’Reilly2016; Mack et al. Reference Mack, Weeks and Wright2010). Patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of the terminal nature of the illness was assessed with the item: “How would you describe your/the patient’s health status: (a) Relatively healthy, (b) Relatively healthy and terminally ill, (c) Seriously ill but not terminally ill, or (d) Seriously and terminally ill.” Responses (a) and (c) were coded as “inaccurate” (not terminally ill) and responses (b) and (d) were coded as “accurate” (terminally ill) terminal illness understanding. Patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of the patient’s life expectancy was assessed by asking: “When you think about your/the patient’s life expectancy, do you think in terms of months or years?” A response of “months” was coded as accurate and “years” as inaccurate life expectancy understanding.

Engagement in ACP was assessed in patients using the Decision Maker (4 items; e.g., “Have you already decided who you want your medical decision maker to be?”) and Quality of Life (4 items; e.g., “Have you already decided whether or not certain health situations would make your life not worth living?”) subscales of the Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey: Action Measures (Sudore et al. Reference Sudore, Stewart and Knight2013). Patients indicate whether they completed each ACP action (yes/no). A total count of “yes” responses for a score range of 0 to 4 is calculated; higher scores indicate greater engagement in ACP (Sudore et al. Reference Sudore, Stewart and Knight2013; Van Scoy et al. Reference Van Scoy, Day and Howard2019). These subscales are reliable and valid measures of concrete ACP behaviors. Caregiver engagement in ACP was assessed with a companion measure of the ACP Decision Maker subscale for caregivers (Van Scoy et al. Reference Van Scoy, Day and Howard2019).

Completion of advance directives was assessed by asking patients whether they completed a DNR order and living will and identified a health-care proxy and/or durable power of attorney. To examine changes in completion of advance directives, a total score was computed that ranged from 0 = no advance directives completed to 3 = all completed (living will, health -care proxy, and DNR.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, and pre- and post-intervention levels of prognostic understanding, engagement in ACP, and completion of advance directives.

Results

Patient demographic and disease characteristics

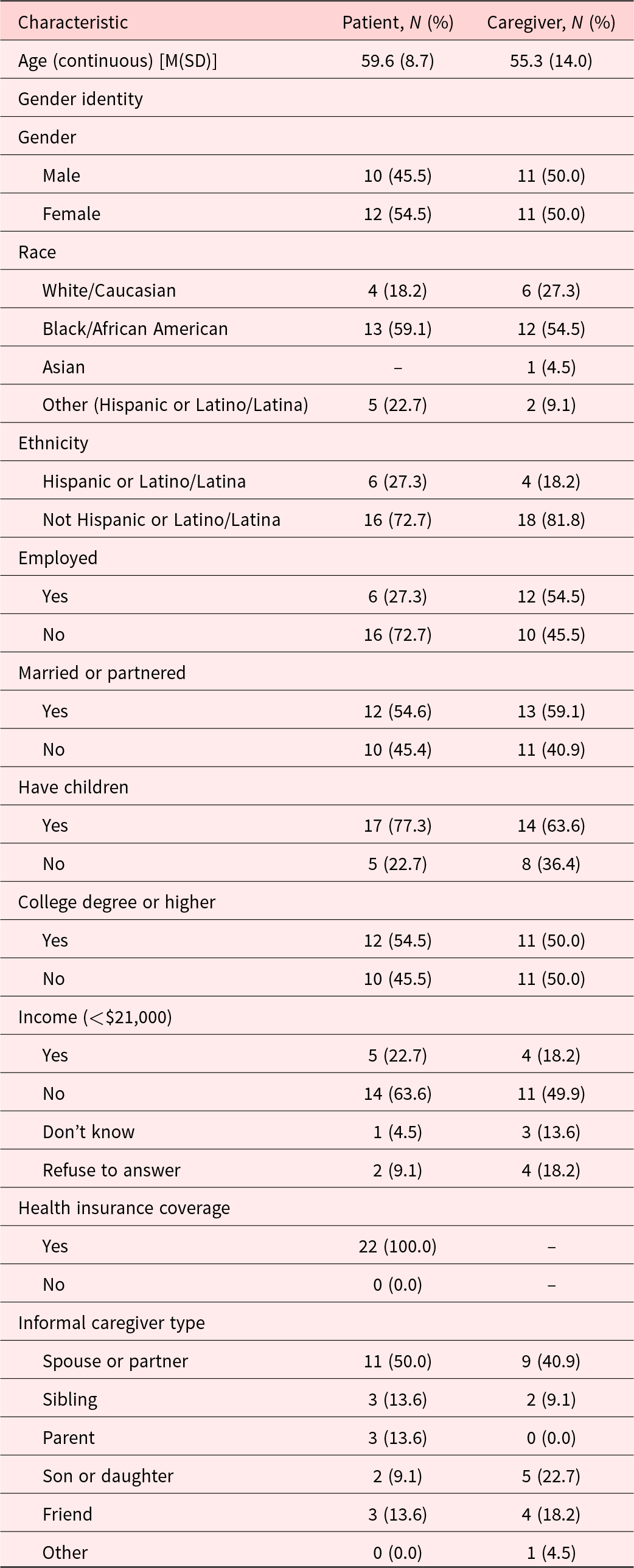

A total of n = 22 dyads (n = 22 patients and n = 22 caregivers) were enrolled in the study. See Table 2 for patient and caregiver demographic characteristics. Patients had a mean age of 59.6 years (SD = 8.7) and 54.5% (n = 12) identified as female. Patient reported race was the following: 18.2% (n = 4) identified as White/Caucasian, 59.1% (n = 13) identified as Black/African American, and 22.7% (n = 5) identified as Other. For ethnicity, a total of 27.5% (n = 6) patients identified as being Hispanic or Latino/Latina.

Table 2. Patient and caregiver demographic characteristics

Caregivers had a mean age of 55.3 years (SD = 14.0) and 50.0% (n = 11) identified as female. Caregiver reported race was the following: 27.3% (n = 6) identified as White/Caucasian, 54.5% (n = 12) identified as Black/African American, 4.5% (n = 1) identified as Asian, and 9.1% (n = 2) identified as Other. For ethnicity, a total of 18.2% (n = 4) caregivers identified as being Hispanic or Latino/Latina. The most common type of relationship with the patient reported was a spouse or partner (40.9%, n = 9), followed by son or daughter (22.7%, n = 5) and friend (18.2%, n = 4). The majority caregivers reported living with the patient (54.5%, n = 12).

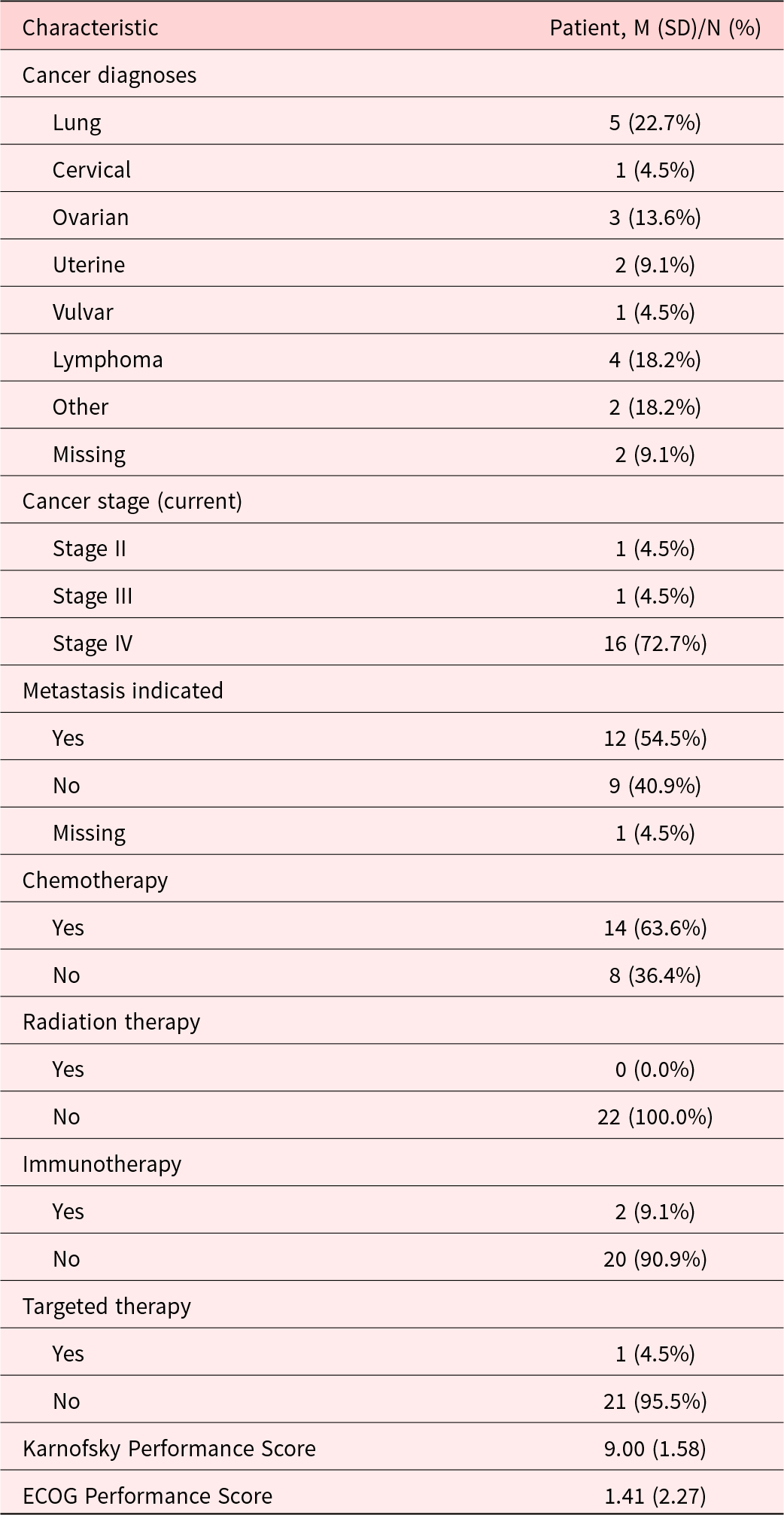

See Table 3 for patient clinical characteristics. The most common cancer diagnoses included lung (22.7%, n = 5), lymphoma (18.2%, n = 2), and ovarian (13.6%, n = 3). The majority (72.7%, n = 16) of patients had stage IV cancer and metastatic disease (54.5%, n = 12).

Table 3. Patient clinical characteristics

Note: All information taken from medical record.

M = mean, SD = standard deviation, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Intervention feasibility

Feasibility was defined in the present study as ≥70% of eligible dyads enrolling in the study (Badr et al. Reference Badr, Smith and Goldstein2015) and ≥70% of dyads who enrolled in the study completing at least 4 of the intervention sessions. A total of 165 patients were attempted to be reached for the study. Of these, n = 91 patients were deemed ineligible, leaving a total of n = 74 patients deemed eligible to approach. Of these n = 74 patients, n = 52 refused to participate before determining full eligibility and n = 22 patients consented to the study and were deemed eligible. Of these 22 patients, all 22 enrolled in the study and completed baseline assessments. Of the n = 22 dyads participating in the intervention (n = 44 participants), n = 15 dyads (68.2%) completed at least the first 4 sessions of the intervention and n = 12 (54.5%) completed all 7 intervention sessions. Session completion was as follows: 1 session (n = 18 dyads), 2 sessions (n = 17 dyads), 3 sessions (n = 16 dyads), 4 sessions (n = 15 dyads), 5 sessions (n = 14 dyads), and 6 and 7 sessions (n = 12 dyads). The most common reason for attrition among dyads included time constraint (n = 3), lost to follow-up/passive withdrawal (n = 3), and too weak to complete (n = 1).

Intervention acceptability

Among the 22 dyads who enrolled in the study and completed baseline measures, 13 patients and 12 caregivers provided post-intervention data. Of these, n = 12 dyads were full completers (i.e., all 7 sessions), and 1 patient was a semi-completer (i.e., <7 sessions). All patients who had post-intervention data (n = 13) rated the intervention as helpful (n = 11 rated it as a “5” or very helpful; n = 2 rated it as a “4”). Most patients (n = 9, 69.2%) indicated the intervention had an acceptable number of sessions. Most patients (n = 11, 84.6%) indicated that the session frequency of weekly was acceptable and that the intervention had the right amount of information. Most patients (n = 12, 92.3%) rated it as “not at all difficult” and were satisfied (92.3%) with participating in the intervention over the telephone.

Similarly, all caregivers (n = 12) rated the intervention as helpful (n = 8 rated it as “5” or very helpful; n = 3 rated it as “4” and n = 1 rated it as “3” or moderately helpful”). Most caregivers (n = 9, 75.0%) indicated the intervention had an acceptable number of sessions. Most caregivers (n = 10, 83.3%) indicated that the session frequency of weekly was acceptable. All caregivers (n = 12, 100.0%) said the intervention had the right amount of information. Most caregivers (n = 11, 91.7%) rated it as “not at all difficult” and reported satisfaction (91.7%) with participating in the intervention over the telephone. Across all 3 measures, the a priori benchmark for intervention acceptability of ≥70% of patients and caregivers scoring ≥4 on the Likert scale items was met.

Treatment fidelity

Fidelity was defined as delivering ≥70% of core intervention components and using ≥70% of the therapeutic techniques. For the core intervention components, interventionists delivered 162 of 208 possible components across all patients and caregivers for a 77.9% fidelity rate. For therapeutic techniques, interventionists used 281 of 288 possible techniques across the sample for a 97.6% fidelity rate, thereby meeting the a priori fidelity benchmark.

Outcomes

Prognostic understanding

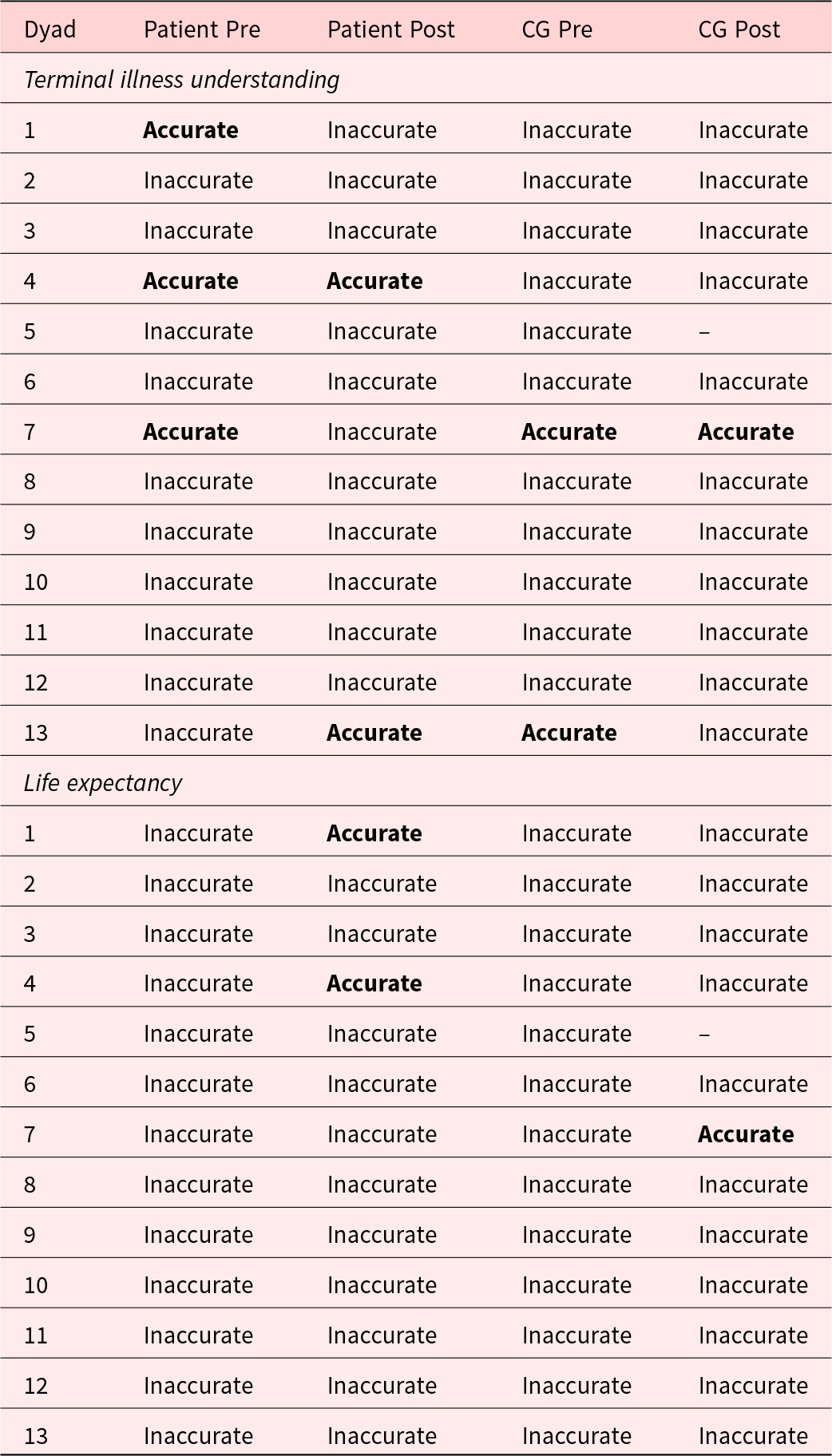

At baseline, 3 of 13 (23.1%) patients had an accurate understanding of the terminal nature of their illness. Post-intervention, 2 of 13 (15.4%) had an accurate understanding. At baseline, 2 of 13 caregivers (15.4%) had an accurate understanding of the terminal nature of the patient’s illness. Post-intervention, 1 of 12 (8.3%) had an accurate understanding. At baseline, 0 of 13 patients had an accurate understanding of their life expectancy (as months, not years). Post-intervention, 2 of 13 (15.4%) patients had an accurate understanding. At baseline, 0 of 13 caregivers had an accurate understanding of the patient’s life expectancy. Post-intervention, 1 of 12 (8.3%) had an accurate understanding. See Table 4 for a breakdown of shifts in prognostic understanding by dyad at the patient and caregiver level. There were no consistent patterns of change within dyads.

Table 4. Patient and caregiver prognostic understanding

CG = caregiver.

Engagement in ACP

Patients reported a mean sum of 2.77 (SD = 1.42) on the ACP Decision-Maker subscale at baseline and a mean of 3.00 (SD = 1.35) post-intervention. Patients reported a mean sum score of 0.69 (SD = 1.03) on the ACP Quality of Life subscale at baseline and a mean sum score of 1.15 (SD = 0.99) post-intervention. Caregivers reported a mean sum of 1.69 (SD = 1.55) on the ACP Decision-Maker subscale at baseline and a mean sum of 1.50 (SD = 1.38) post-intervention.

Completion of advance directives

For DNR order, a total of 1 patient (7.7%) reported having a DNR order at baseline and 4 patients (30.8%) reported having completed 1 post-intervention. For living wills, a total of 2 patients (15.4%) reported completing 1 at baseline and 3 patients (23.1%) reported completing 1 post-intervention. For health-care proxy forms, a total of 6 patients (50.0%) reported completing 1 at baseline and 9 (69.2%) reported completing 1 post-intervention.

Discussion

This pilot single-arm trial examined the feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, and pre-post impact of a communication-based intervention, designed to improve prognostic understanding and engagement in ACP among patients with terminally ill cancer and their caregivers. Results indicate that the TAC intervention was feasible, acceptable, and that the social worker interventionists delivered it with high fidelity. Rates of enrollment exceeded the a priori benchmark while rates of completion fell slightly below the benchmark of feasibility. Still, over half of patients and caregivers completed all 7 sessions of the intervention. Nevertheless, because only about 60% of dyads fully completed the intervention, a reduction in number of sessions appears warranted and may enhance feasibility of the TAC intervention. Patients and caregivers also exceeded the a priori benchmarks for acceptability, with most patients and caregivers rating the intervention as very helpful, an acceptable length, and not at all difficult. Further, patients and caregivers were satisfied with telephone delivery of the intervention. Intervention fidelity was extremely high and greatly exceeded a priori benchmarks for fidelity.

Preliminary intervention testing was limited by the small sample size; however, results indicate a trend towards an increase in completion of advance directives but not in prognostic understanding or engagement in ACP. This finding may be because the TAC intervention had an entire session devoted to specifics around how to complete advance directives (session 6), whereas prognostic understanding was discussed more generally. TAC content around prognostic understanding focused on how to talk about prognosis with one’s doctor and about poor prognosis in general. Information on an individual’s prognosis was not provided during the intervention, as this is outside the scope of practice for mental health providers. Because there was a shift in some patients’ and caregivers’ prognostic understanding from accurate to inaccurate, there is a clear need for further refinement of TAC’s discussion of prognostic understanding. Additionally, future iterations of delivering TAC may need more direct involvement or communication about prognostic understanding from the medical team.

In contrast to the findings around prognostic understanding, results from this study indicate the potential for TAC to improve advance directive completion is promising. Information in TAC on the nature and importance of advance directives and how to complete them is concrete and applicable to patients with varying levels of prognostic understanding, and preliminary results indicate trends in the direction of increases in engagement in advance directive completion. Given the limited efficacy of prior interventions targeting advance directive completion, this is an especially promising finding. A systematic review across 55 studies found that ACP interventions increase completion of advance directives at very limited rates (e.g., a 5% increase in completion of health-care proxy forms (Rubin et al. Reference Rubin, Strull and Fialkow1994)). More recent interventions yield more promising results with advance completion rates as high as 35% (Sudore et al. Reference Sudore, Boscardin and Feuz2017), yet there remains significant room for improvement.

A significant strength of this study is the racial and ethnic diversity of the study sample. Racial and ethnic minority patients, particularly patients identifying as black or Hispanic or Latino, suffer from significantly lower rates of advance directive completion than white patients (Carr Reference Carr2011; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Henderson and Hyer2021; LoPresti et al. Reference LoPresti, Dement and Gold2016). The inclusion of caregivers in TAC is particularly important for patients from racial and ethnic minority groups for whom caregivers play an especially prominent role in patient decision-making and care (Mead et al. Reference Mead, Doorenbos and Javid2013). Furthermore, integration of caregivers into the ACP process is an explicitly expressed preference of patients from racial and ethnic minority groups (Sanders et al. Reference Sanders, Johnson and Cannady2019; Shen et al. Reference Shen, Gonzalez and Leach2020). Despite this high need, few ACP interventions have taken a dyadic approach to the ACP process. As such, TAC holds promise as a potentially effective intervention to improve advance directive completion among Black and Hispanic or Latino patients and reduce racial disparities in ACP.

TAC was developed with feedback from a variety of patients, including Hispanic/Latino and Black patients. As a result, some cultural tailoring occurred during the intervention development process. However, cultural tailoring was not a primary focus in this preliminary process and the open trial described here revealed additional needed changes to improve cultural specificity. For instance, although attempts were made to make an intervention that could be administered to multiple racial and ethnic groups, variations in cultural norms around prognosis and prognostic discussions may necessitate more specific tailoring for each racial and ethnic groups and/or socioeconomic class. Such tailoring may result in more effective targeting of prognostic understanding. Additionally, highly under resourced dyads including those who were unhoused and living in shelters were eager to participate in the TAC intervention. Many dyads were unable to finish all 7 sessions due to obstacles such as time restraints and limited access to a phone. Future research that identifies unnecessary content to reduce the number of TAC sessions may improve feasibility, particularly for patients with resource limitations.

Combined, preliminary data indicate that future modifications need to be made to not only culturally tailor but overall improve TAC’s feasibility and potential efficacy. First, future content should focus more explicitly on prognostic understanding. The current content is likely too vague and focuses on simply guiding dyads in how to have conversations with their providers. This may not have been a direct enough form of communication about prognosis. Future research should examine best ways to be more explicit about poor prognosis and potentially integrate the medical team more directly. Second, TAC should incorporate more material that focuses on guiding dyads in how to engage in ACP, including checklists for specific tasks to complete in the ACP process. Finally, TAC would benefit from shortening the number of sessions. For instance, the topic of ACP was a feature of the intervention dyads reported liking, while many noted that the distress management and communication techniques were too basic or did not need to be covered in such great detail. As such, Sessions 1 through 5 could be shortened to focus on core components of distress management and communication techniques. This would allow for a greater focus on prognostic understanding and ACP while shortening the intervention.

Limitations of the study must be acknowledged in interpreting results. First, the small sample size and pre–post design limits the ability to examine the efficacy of TAC, control for factors (e.g., demographic variables) that may impact treatment effects, and generalize study findings. As such, a larger randomized controlled trial is needed to examine the efficacy of this intervention on engagement in ACP and advance directive completion. In addition, future larger studies should examine the impact of TAC on care received at the EOL with a focus on provision of care that is consistent with patients’ preferences. Second, this study was conducted at 2 major academic medical centers in an urban setting which limits the generalizability of study findings. However, 1 site provided care to a historically underserved patient population which is a notable study strength. Third, patients and caregivers were excluded from the study if both had an accurate prognostic understanding; however, it is possible these individuals may have needed assistance with advance directive completion and, therefore, could have benefitted from the intervention.

Conclusion

In summary, results from this study indicate that the TAC intervention is feasible and acceptable with the potential to improve advance directive completion among Black and Hispanic or Latino patients with advanced cancer. These findings point to a possible new intervention designed to target patients’ engagement in ACP through integration of their caregivers in this process. Future research is needed to further refine and optimize TAC to diverse patient and caregiver populations and to examine the efficacy of TAC to improve engagement in ACP and advance directive completion and increase rates of preference-concordant end-of life care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Madeline Rogers, Claudia De Los Santos, Robin Hershkowitz, Amy Stern, Jasmine Monterio, Chrystal Marte, and James Lassen for their work in delivering the intervention (MR, RH, AS, JM), providing feedback, (MR, CDLS, JM), and helping coordinate and oversee patient recruitment (CDLS, CM, JL).

Competing interests

None.