Prosopometamorphopsia is the distortion of visual perception occurring when viewing faces, either in person or in photographs. Lesions or abnormal activity in the right medial temporo-occipital lobe, parieto-occipital lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe, putamen and restrosplenial region have been associated with prosopometamorphopsia.Reference Miwa and Kondo 1 We report a case of right hemi-prosopometamorphopsia secondary to a small acute ischemic infarct in the splenium of the corpus callosum on the left.

A 56-year-old female presented with chest pain, elevated troponin and creatine kinase, and promptly underwent coronary catheterization. As the procedure was completed, she experienced a sudden-onset visual change. When she looked at the nurse assisting with the procedure, she noticed a “funhouse mirror effect” in the left half of the nurse’s face, correlating to the patient’s right visual field. This half of the face appeared to be laterally elongated, and the left eye appeared more oval than the right.

Her neurological exam was otherwise normal. She did not have any features of a disconnection syndrome such as unilateral tactile anomia, unilateral agraphia, unilateral apraxia, or somesthetic transfer abnormality. No abnormalities in vision were reported when she viewed an Amsler grid. When she placed her own hand in front of the distorted side of her visual field, she could see the hand clearly but the facial distortion behind the hand would persist. The presentation of the face, whether it was in person, in magazines or using electronic devices, did not affect the amount of distortion perceived. The distortion was only present when she looked at faces. There was an angle-dependent difference in her facial perception. When a face was directly facing her, the facial distortion started at midline and extended to the left side of the face. When she looked at a face that was turned 45° to the left, she was able to visualize the entire face with no metamorphopsia. When it was turned 45° to the right, distortion manifested in the whole face. Her prosopometamorphopsia was also affected by the familiarity of the face. The distortion was worst when she looked at the face of a stranger, and alleviated slightly on visualizing the same face multiple times.

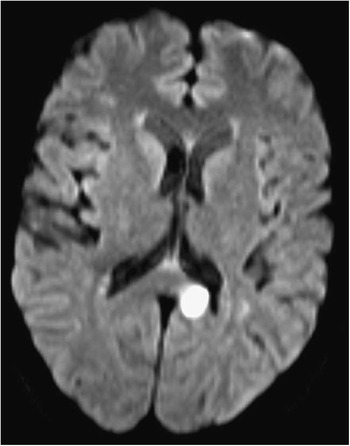

MRI of her brain three days after the onset of her symptoms confirmed a small acute ischemic infarct in the splenium of the corpus callosum on the left (Figure 1). A follow-up MRI five weeks later showed a now chronic infarct with less mass effect in the surrounding area (Figure 2). A follow-up neuro-ophthalmological assessment did not reveal any ophthalmological lesion. At the time of the second MRI, she continued to have prosopometamorphopsia, and at last follow-up about eight months later her symptoms were persistent.

Figure 1 Diffusion weighted imaging 3 days after onset of prosopometamorphopsia, showing infarction of the splenium of corpus callosum on the left.

Figure 2 T2-weighted image five and a half weeks after the onset of prosopometamorphopsia, showing chronic infarction of the splenium of corpus callosum on the left.

To the best of our knowledge, six cases involving a similar lesion with similar symptoms have been published. Our case is unique in that our patient’s prosopometamorphopsia was affected by the familiarity of the face viewed and by the angle at which the face was visualized. We hypothesize that the ischemic infarct in our case disrupted the connection pathway responsible for the transmission of information from the left fusiform gyrus and inferior occipital gyrus to the right hemisphere, thereby selectively disturbing facial perception. The importance of interhemispheric connections for facial recognition has been recognized in the past. For example, the fMRI study of facial recognition by Zhen et al.Reference Zhen, Fang and Liu 2 demonstrated that there was a strong temporal correlation in synchronized neural activation between interhemispheric pairs of homologous regions, in particular the left and right fusiform gyri. Facial recognition likely involves a hierarchy of interconnected networks. The inferior occipital gyrus and fusiform gyrus are involved with facial identity, the middle frontal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrus assess semantic information, and the superior temporal sulcus, orbital frontal cortex and insular cortex process facial expression. This complex network also differentiates between familiar and unfamiliar faces. In addition to facial identification areas, a familiar face activates brain regions associated with representation of semantic, episodic and emotional information, making familiar face recognition more accurate.Reference Natu and O’Toole 3 Interestingly, lesion location can affect the perception of familiar and unfamiliar faces differently. A patient with a right temporal/occipital area haemorrhage suffered from prosopometamorphopsia that was worse with familiar faces.Reference Bala, Iwanski, Zylkowski, Jaworski, Seniów and Marchel 4 This may suggest that the temporo-occipital area is more important for recognizing familiar faces, while the splenium of the corpus callosum, which was affected in our case, is more selective for unfamiliar face perception. Unfortunately, none of the previous case reports involving prosopometamorphopsia caused by splenium or retrosplenial lesions have documented any difference in examining unfamiliar and familiar faces. Therefore, the hypothesis of splenium lesions preferentially disrupting the perception of unfamiliar faces remains to be further explored.

An additional interesting feature in our case is that there is a view-dependent aspect in prosopometamorphopsia. This is consistent with the theory that unfamiliar faces are perceived in a view-dependent manner, as demonstrated by Zimmermann et al.,Reference Zimmermann and Eimer 5 whereas familiar faces are likely perceived in a view-independent manner. This further supports our hypothesis that a lesion in the splenium is more selectively involved in the perception of unfamiliar faces. Currently, we only have a rudimentary understanding of the complex processes involved in human facial recognition and perception. There remains great potential for further elucidation of this fascinating process, especially as functional imaging modalities improve.

Statement of Authorship

Drs. Jiang and Jin co-wrote the manuscript, with assistance from Dr. Sasikumar, who helped gather the clinical information relevant to this case. Dr. Jin provided editorial oversight.

Disclosures

Yue Jiang, Sanskriti Sasikumar, and Albert Jin hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.