Stress-related illnesses are a major threat to public health in the Western world.1 In Denmark, it has been estimated that stress-related illnesses are linked to 300 000 admissions to hospital and 1400 premature deaths every year with an annual cost to society amounting to DKK 14.7 billion.Reference Juel, Sorensen and Bronnum-Hansen2 Consequently, there is growing international and national demand for interventions both to prevent and to treat stress-related illnesses.1, 3–5 The Danish Health Authority recommends various forms of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) treatments to help patients recover from stress.5 Many alternative treatments exist, but evidence of the efficacy of these various stress treatments is limited. One alternative treatment is nature-based therapy (NBT), which refers to a therapeutic intervention that incorporates natural elements and nature-related activities often in a specially designed natural environment.Reference Corazon, Stigsdotter, Jensen and Nilsson6 NBT has its origins in Anglo-American countries and has a relatively long history of use in healthcare.Reference Marcus and Barnes7

State of the art

A number of review articles have been published focusing on the effect of NBT for specific patient groups, such as elderly peopleReference Detweiler, Sharma, Detweiler, Murphy, Lane and Carman8 and war veterans.Reference Poulsen, Stigsdotter and Refshauge9 In 2011, Annerstedt & Währborg published what remains the most comprehensive literature review of the effects of various forms of NBT on different patient groups, including both controlled and observational studies.Reference Annerstedt and Währborg10 Annerstedt & Währborg agree with other researchers (for example Stigsdotter and colleaguesReference Stigsdotter, Palsdottir, Burls, Chermaz, Ferrini, Grahn, Nilsson and Sangster11) that current research on NBT focuses too much on qualitative data, and they recommended that future studies be conducted as randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Study aim

This study aims to test the efficacy of a specific NBT treatment called Nacadia® NBT (NNBT) by conducting a RCT (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01849718) that compares NNBT with a CBT called Specialised Treatment for Severe Bodily Distress Syndromes (STreSS). The null hypothesis is: the efficacy of NNBT will not differ significantly from the efficacy of STreSS, measured by mental health metrics. The research questions are as follows: (a) has the mental health status of the participants improved after treatment (compared with baseline), immediately afterwards, and then 3, 6 and 12 months after the end of the treatment; (b) are there significant differences between the two forms of treatment in terms of improved mental health?

Method

Trial design

The efficacy of treatments relying on CBT has been widely documented,Reference Butler, Chapman, Forman and Beck12 and CBT is recommended by the Danish Health Authority for treating stress-related illnesses.5 The efficacy of NNBT was, thus, compared with a validated CBT treatment.Reference Schröder, Rehfeld, Ørnbøl, Sharpe, Licht and Fink13 The trial was designed as an equivalence trial to assess whether NNBT (intervention) would be as effective as STreSS (control) in treating patients with stress-related illnesses (the full trial protocol is provided as Supplementary File 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.2). Participants were individually and equally randomised to one of the two parallel treatments, and the same outcome measures were employed. No changes were made to the methods after the trial had commenced.

Participants

Potential participants were referred to the project by the municipalities, health practitioners (private practice doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists), and insurance companies in the area around the Nacadia® therapy garden, which is located in the Municipality of Hørsholm in Denmark (material on recruitment is provided as Supplementary File 2). The municipalities, health practitioners and insurance agencies had been notified about the project by an information letter describing the project and the two treatments. The letter was followed up by personal contact by the managing therapist at the Nacadia therapy garden. Potential participants also contacted the University of Copenhagen directly in response to brief notices in newspapers and on the university webpage informing the public about the project. In total, 200 potential participants were assessed for eligibility. All individuals needed to provide a health certificate from their medical doctor and approval to participate from their municipal case officer. A PhD student conducted a telephone interview and those participants who were considered likely to meet the inclusion criteria were then invited to undergo a clinical assessment. The assessment was conducted by one of four clinical psychologists, and the diagnoses were supervised and confirmed by a psychiatrist.

To be eligible for participation, individuals had to be incapable of working and have one of the ICD-10 codes14 F43.0, 2–9 as their primary diagnosis (psychiatric diagnosis of adjustment disorder and reaction to severe stress). The level of severe stress was considered to correspond to 3–24 months of inability to work according to the Danish Health Service. Adults aged 20–60 years were included. Individuals with severe psychiatric morbidity, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, suicidal tendencies and drug or alcohol problems were excluded. For practical reasons, individuals who were not fluent in the Danish language were excluded. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 84 participants were enrolled in the study.

The study followed the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J.no. 2013-54-0344) and by the National Committee on Health Research Ethics (P.no. H-1-2013-038). Participants received both oral and written information about the study and signed an informed consent acknowledgement before enrolment.

Settings

The treatments took place in two different types of settings: STreSS took place indoors at private clinics of the practising psychologists located in the city of Hørsholm, and NNBT took place mainly outdoors at the University of Copenhagen's therapy garden called Nacadia. This garden has been designed as a 1.4-hectare wild forest garden and is located within an arboretum containing the largest collection of trees and shrubs in the country. The design of the garden follows the model for evidence-based health design, and the design process has been transparently described and documented.15

Treatments

Apart from the difference in environments, the two treatments also differed with regard to staff, hours, content and set-up: in NNBT, two therapists and a gardener were involved in the therapy, which consisted of 3 h group sessions with individual therapeutic conversation and individual nature-based activities introduced by the gardener. STreSS was conducted as individual 1 h therapeutic conversation sessions with one therapist. Although NNBT was carried out with a group of participants present in the Nacadia garden, most of the activities were individual, and participants were encouraged not to interact during the sessions and to keep talk to a minimum. Therefore, one can argue that NNBT is a hybrid between a group-based and an individual treatment.

The corresponding elements between the two treatments were as follows: the therapists were all licensed clinical psychologists with formal training in CBT; the length of treatment time was 10 weeks; the individual treatment conversations were based on CBT; and the two treatments took place simultaneously all year round from August 2013 to March 2015, except during the winter and summer holidays. (For an overview of differing and corresponding elements, see Supplementary File 3).

CBT

The control group received a form of CBT called STreSS, which was originally developed at Aarhus University.Reference Rehfeld, Schröder and Fink16 STreSS consists of nine modules of manualised CBT, and the efficacy of this treatment has been tested in an RCT.Reference Schröder, Rehfeld, Ørnbøl, Sharpe, Licht and Fink13 STreSS was originally designed for group treatments. In this project, the manual was adjusted to individual treatments in order to better to match the individual parts of NNBT. The adjustments were elaborated in dialogue with the leader of the Aarhus University group, who developed the treatment manual (in Danish) under the supervision of the psychiatrist in the project (from Aarhus University) and the person responsible for conducting CBT in the project (from the University of Copenhagen). The individual STreSS sessions relied on the same nine modules as did the group treatment.Reference Rehfeld, Schröder and Fink16

NNBT

NNBT was originally developed by Corazon and collegues.Reference Corazon, Stigsdotter, Jensen and Nilsson6 It builds upon elements from mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR)1Reference Marcus and Barnes7 and CBT, integrated with theories from environmental psychology, especially attention restoration theory, which emphasises sensory stimulation from natural environments as a means of restoring fatigued cognitive resources.1Reference Detweiler, Sharma, Detweiler, Murphy, Lane and Carman8

NNBT is a 10-week programme, and participants met 3 days a week for 3 h. Every day has the same structure, and every week has a specific theme in accordance with a MBSR manual.Reference Fjorback19

NNBT consists of the following five components.

(a) Therapeutic conversations: individual conversations based on CBT and psychoeducation based on MBSR.

(b) Awareness exercises: individual and group physical and mental awareness exercises in accordance with MBSR and related to nature experiences, such as mindful walking in the garden.

(c) Nature-based activities: individual gardening activities, dependent on the season. Before each session, the gardener, who also maintains the therapy garden, makes a list of possible activities from which the patients choose together with the therapist. The choice of activity is guided by what is comprehensible, manageable and meaningful for the individual.Reference Antonovsky20 Mindful awareness is integrated into the activities. That is, participants are trained to notice non-beneficial behavioural patterns that could lead to stress.

(d) Reflection and relaxation time: individual time for reflection and relaxation in the garden.

(e) Homework: individual homework to practice the different techniques and methods.

Outcome measures

Participants in both treatments completed the same self-rated measures in the form of two questionnaires at five different points in time: at baseline (first week of treatment), at the end of treatment (primary end-point measure), and at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after treatment had ended. The three measures after the primary end-point measure were included to assess whether an effect was sustained after treatment had ended. The questionnaires at baseline and at end of treatment were given to participants by the therapists. The subsequent questionnaires (after 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months) were sent by post to the participants.

The primary outcome was the aggregate score (global score) on the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI), which measures the self-assessed perceived well-being and distress.Reference Chassany, Diderot and Dubois21, Reference Lundgren-Nilsson, Jonsdottir, Ahlborg and Tennant22 The PGWBI includes 22 questions in relation to six subscales: anxiety, depressed mood, positive well-being, self-control, general health and vitality. Each item has six response options, ranging from 0 to 5. The aggregate score was calculated as the sum of scores on the six subscales,Reference Chassany, Diderot and Dubois21 giving an aggregate score range of 0–110 with higher values indicating greater well-being.

The secondary outcome measure was the mean total score of the Shirom–Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ). It consists of 22 items, divided into four subscales: physical fatigue, cognitive weariness, tension and listlessness. The questionnaire is validated through research.Reference Lundgren-Nilsson, Jonsdottir, Pallant and Ahlborg23

Additionally, participants completed a background questionnaire at baseline. The background questionnaire contained questions regarding demography, educational level, employment status and health.

Sample size and randomisation

The minimum sample size was determined in a power calculation (2-sample t-test: α = 0.05, 95% CI; expected s.d. = 14.5; β = 0.8; P < 0.05) (program: Excel). A sample of 40 participants in each treatment (80 participants in total) was estimated to be able to identify a mean difference in efficacy of 9.2 between treatments. Since recruitment took place throughout the intervention on a running basis, it was possible to account for individuals who dropped out during the recruitment phase, by recruiting more individuals if drop out occurred.

Participants were evenly and randomly allocated to one of the treatments using a computer algorithm. Each participant was allotted a random number between zero and one. Participants with a number below the median value were randomised to receive NNBT (n = 43), and participants with a number above the median value received STreSS (n = 41). The allocation sequence was generated by a statistician and administered by an independent research assistant, who also assigned participants to the two different treatments.

Statistical analysis

The data was analysed based on intention-to-treat (ITT), whereby participants were analysed within the treatment to which they were allocated, irrespective of non-adherence or deviations from protocol.Reference Lindquist24 ITT is the recommended approach in RCT trials provided by the Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.Reference Alshurafa, Briel, Akl, Haines, Moyyedi and Gentles25 The CONSORT 2010 checklist can be found in Supplementary File 4. However, there is no consensus regarding how to handle missing outcome data within ITT.Reference Lindquist24, Reference Alshurafa, Briel, Akl, Haines, Moyyedi and Gentles25 In the present trial, we used the numerical imputation strategy of last observation carried forward (LOCF), which is a common approach in RCT trialsReference Schulz, Altman and Moher26 and recommended by Hollis & Campbell in a survey of RCTs.Reference Hollis and Campbell27 The LOCF strategy was chosen in order to include participants who happened not to fill out a questionnaire at some time points. As a complementary analysis, a complete case analysis was also performed in which individuals with missing outcome data were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome data had 36 missing responses to single questions within the PGBWI questionnaire out of 8360 questions (0.4%). The missing responses were estimated using the approach suggested in Chassany et al.Reference Chassany, Diderot and Dubois21 The Shapiro–Wilk test, skewness and kurtosis values, together with a visual inspection of the histograms and the box plots of the sample distributions were used to detect any deviations from normal distribution. Levene's test (the parametric or non-parametric version) was used to reveal any heterogeneity of variance among the five ‘points in time’ samples within a treatment or the between-treatment samples at a given point in time.

Primary outcome (PGWBI)

A two-way mixed-design ANOVA (2 × 5) was employed to detect any significant effect within a treatment over time and any difference between the two treatments. Effect sizes for each treatment were calculated (partial η2 and ω2) based on the one-way repeated-measures ANOVA of each treatment. Within groups, we compared each timepoint with baseline to detect by which point in the study any change may have occurred. Multiple comparisons were corrected for using Dunnett's method.

Secondary outcome (SMBQ)

Friedman's test was used to reveal any significant effect over time within a treatment. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed for post hoc multiple pairwise comparisons between points in time (including adjustment of the significance level to P < 0.0071, using the Bonferroni correction for seven pairwise comparisons). Mann–Whitney U-tests were performed for post hoc pairwise comparisons between the two treatments at each point in time (including adjustment of the significance level to P < 0.01, using the Bonferroni correction for five pairwise comparisons).

The statistical analyst was first introduced to the project once the data from the questionnaires had been compiled. The statistical analyst was not informed whether either of the treatment abbreviations was preferred over the other.

Results

Participant flow

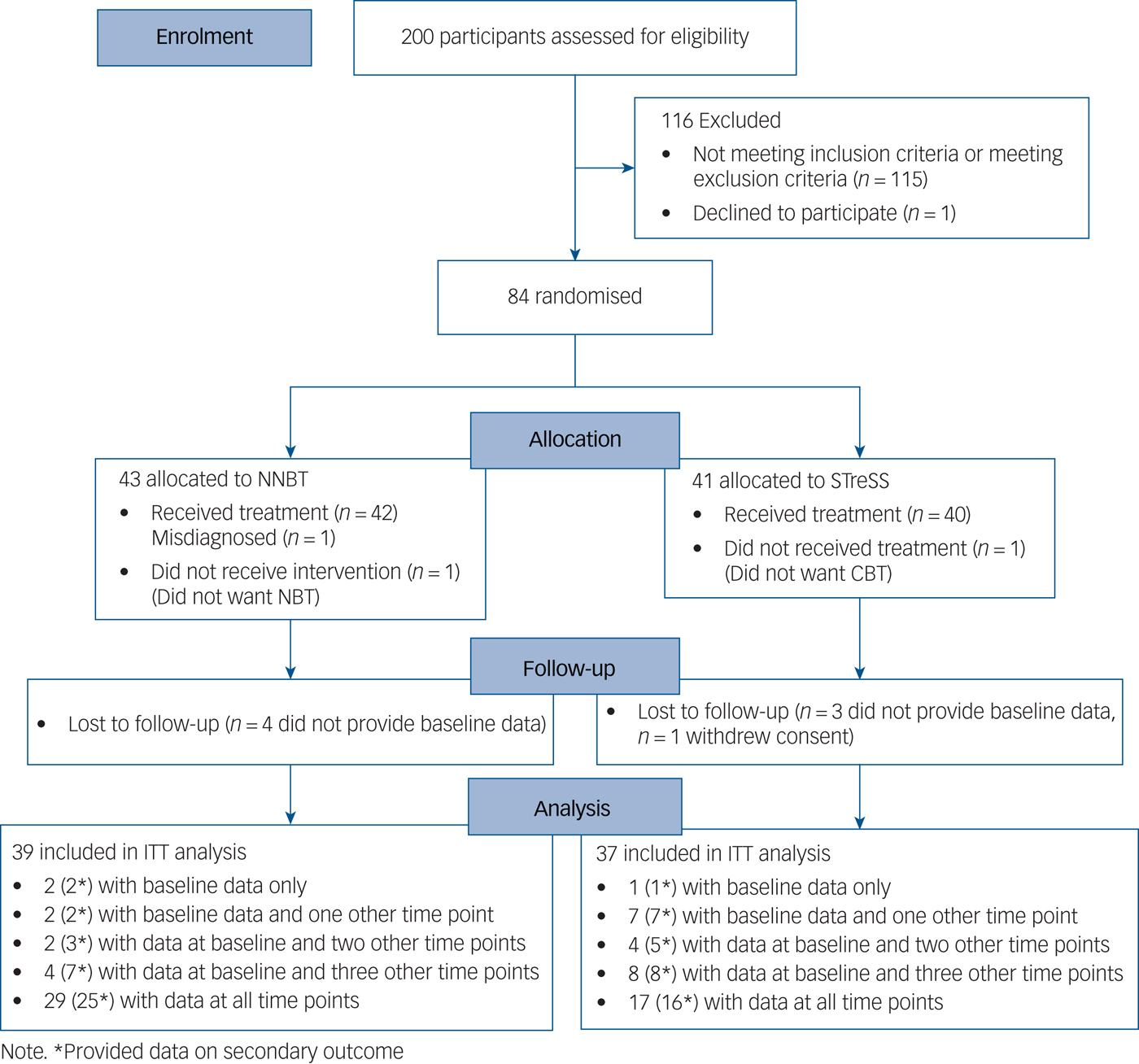

Recruitment of participants occurred from 2 months before the treatments started until the beginning of the last treatment period, that is, from June 2013 to January 2015. In total, seven NNBT treatments were conducted (median group size: 6). Of the 43 participants assigned to NNBT and 41 patients assigned to STreSS, 42 participants completed NNBT and 40 participants completed STreSS. In each treatment, four participants were lost to follow-up (see Fig. 1 for participant flow).

Fig. 1 Participant flow diagram. NNBT, Nacadia nature-based therapy; STreSS, Specialised Treatment for Severe Bodily Distress Syndromes; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; ITT, intention-to-treat.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of participants in relation to demography, education, employment status and sick leave are presented in Table 1. The vast majority of participants were women. The majority of respondents held a bachelor's degree or higher university education. The respondents were mainly employed but on full-time sick leave. The most common previous rehabilitation initiatives had involved visiting a general practitioner or a psychologist.

Table 1 Participants’ baseline characteristics

a. The data from the background questionnaires included missing responses to single questions; therefore, the sum of responses for the different variables does not match the total number of respondents for Nacadia nature-based therapy (NNBT) (n = 39) and Specialised Treatment for Severe Bodily Distress Syndromes (STreSS) (n = 37), respectively.

Primary outcome (PGWBI): sample characteristics

The samples showed no significant deviations from the normal distribution (P > 0.05). There was neither a significant heterogeneity of variance among samples within a treatment nor any heterogeneity of variance between samples of the two treatments at any given point in time (P > 0.05).

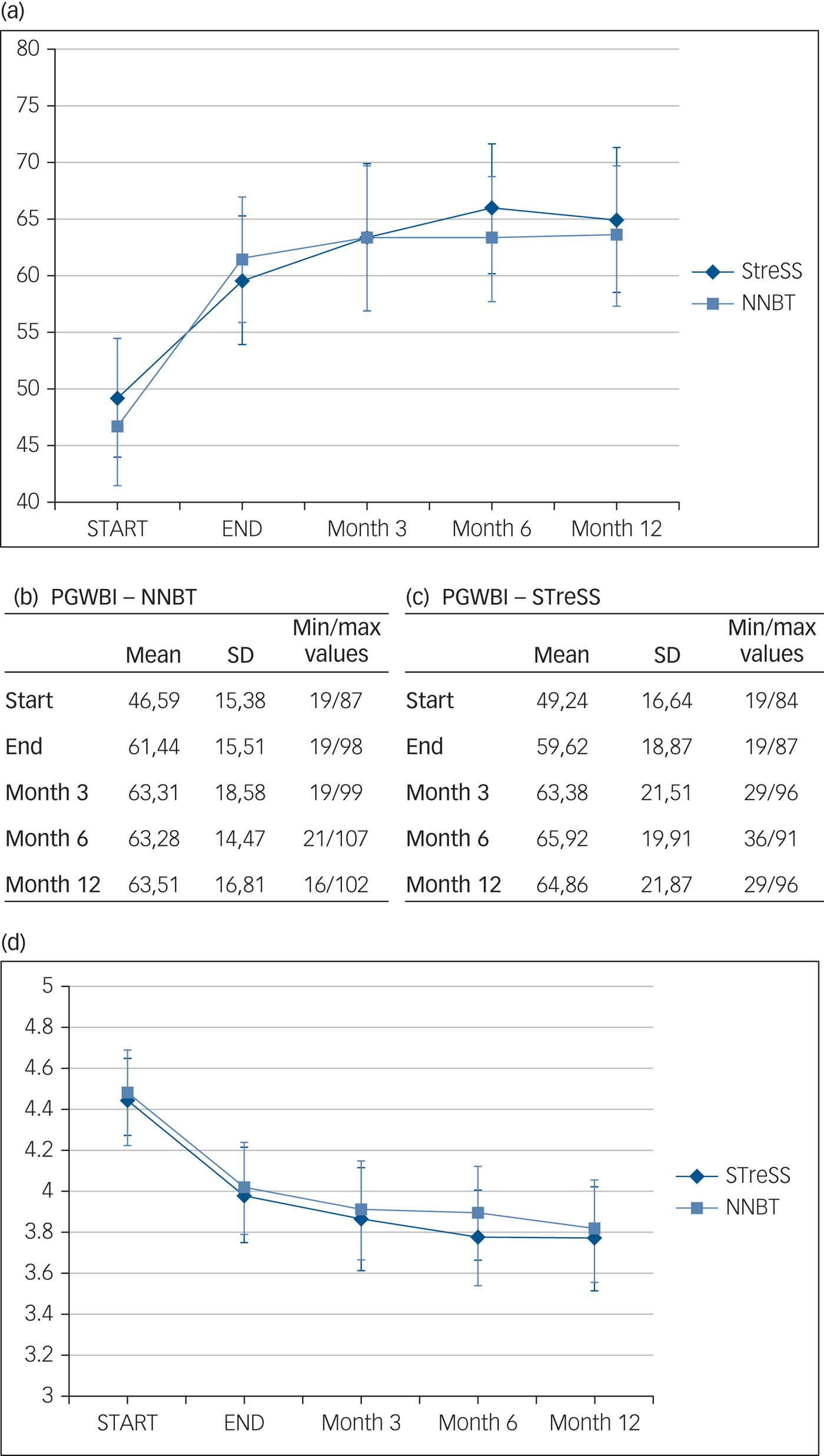

Primary outcome (PGWBI): results from the LOCF analysis

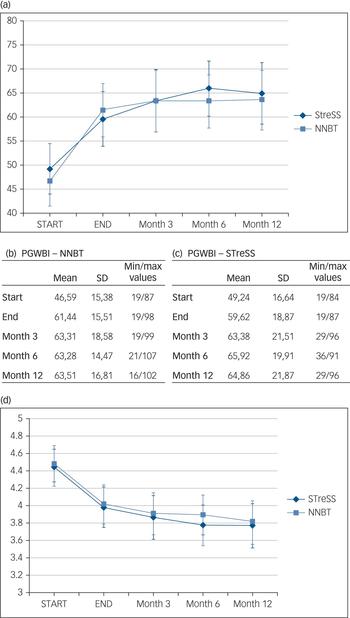

There was a significant effect of treatment on perceived general well-being (PGWBI) over time, F(4,144) = 5.23, P < 0.01, overall partial η 2 = 0.13, and no significant difference between treatments, F(1,36) = 0.39, P > 0.05, overall partial η2 = 0.01 (see Fig. 2(a–c)). NNBT had effect size estimates indicating a medium to large effect of treatmentReference Cohen28 (η 2 = 0.144; ω2 = 0.125). STreSS had effect size estimates indicating a medium effect of treatment (η2 = 0.088; ω2 = 0.067).

Fig. 2 The effect of Nacadia nature-based therapy (NNBT) and Specialised Treatment for Severe Bodily Distress Syndromes (STreSS) on (a–c) Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) scores and on (d) Shirom–Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ) scores. (a) The effect of NNBT on the primary outcome (PGWBI) with 95% confidence intervals. The mean aggregate score, standard deviation and minimum and maximum values for PGWBI in the (b) NNBT group and (c) STreSS group. (d) The effect of NNBT on the secondary outcome (SMBQ) with 95% confidence intervals.

The post hoc test showed there was a significant difference in PGWBI scores between the start of treatment and the end of treatment for both the STreSS (P < 0.05) and NNBT groups (P < 0.001) (Table 2). There was also a significant difference in PGWBI scores between the start of treatment and each subsequent time point (i.e. at 3, 6 and 12 months after the treatment). Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the end of treatment and each subsequent time point for either NNBT or STreSS (Table 2).

Table 2 Multiple comparisons between time pointsa

NNBT, Nacadia nature-based therapy; STreSS, Specialised Treatment for Severe Bodily Distress Syndromes.

a. The within-group comparison of treatment effect over time, using a particular time point as reference. Time point i is the reference point in time (control), to which each of the subsequent time points (j) is compared. CI (confidence interval) is relating to the range around the calculated Mean Difference (j-i) value.

The results from the complete case analysis (from which participants with missing outcome data were excluded) largely corresponded with the results from the LOCF analysis. These are presented in Supplementary File 5.

Secondary outcome (SMBQ): sample characteristics

The samples showed significant deviations from the normal distribution (P < 0.05 for several of the sample distributions). Efforts to establish normal distributions using various types of transformations were unsuccessful. There was no significant heterogeneity of variance among samples within a treatment or between samples of the two treatments at specific points in time (P > 0.05).

Secondary outcome (SMBQ): results

There was a significant effect of treatment over time for STreSS (χ2(4) = 33.15, P < 0.001) and for NNBT (χ2(4) = 45.35, P < 0.001) (see Fig. 2(d) for visual representation).

A significant effect of treatment was observed between the start of treatment and all succeeding points in time (i.e. end of treatment or after 3, 6 or 12 months) for both the STreSS and NNBT groups (see Supplementary File 6). There was no significant pairwise difference in SMBQ scores between any of the remaining time points.

Discussion

Main findings

Both the intervention (NNBT) and the control treatment (STreSS) showed significant effects at the end of treatment (main end-point measure). These were expressed as a higher aggregate general well-being score (PGWBI, primary outcome) and a lower average burnout score (SMBQ, secondary outcome). No significant difference was found between the two treatments with regard to primary and secondary outcomes. The effect was sustained at all time points after treatment. The mean aggregate score of the PGWBI 12 months after end of treatment (NNBT: mean 63.51; STreSS: mean 64.86) approached the reported value for a Danish healthy sample (mean 73.14), provided by the MAPI Institute.Reference Chassany, Diderot and Dubois21

Having a RCT with long-term follow-up in the field of NBT provides a good opportunity to validate its efficacy and promote recognition of the field, which has until recently relied mostly on qualitative research lacking long-term follow-up.Reference Annerstedt and Währborg10, Reference Stigsdotter, Palsdottir, Burls, Chermaz, Ferrini, Grahn, Nilsson and Sangster11 Several municipalities in Denmark have expressed interest in including NNBT in their treatment of citizens with stress-related illnesses, but lack of evidence of its efficacy has been an obstacle.

It should be emphasised that the various NBT treatments on the market differ substantially in content,Reference Annerstedt and Währborg10, Reference Stigsdotter, Palsdottir, Burls, Chermaz, Ferrini, Grahn, Nilsson and Sangster11 meaning that results cannot be generalised to the entire field of NBT for stress-related illnesses. The results relate, instead, to the present form of NNBT used in the intervention. NNBT can be seen as a complex intervention;Reference Campbell, Fitzpatrick, Haines, Kinmonth, Sandercock and Spiegelhalter29 and, as a consequence, it is difficult to deduce what caused the effect. One could argue that some of the possible mechanisms involved in accommodating the effect of NNBT are shared among NBT treatments in terms of spending time in a natural environment when feeling stressed.Reference Donner, Birkett and Buck37 Other mechanisms are potentially related to the interrelationship of the specific psychotherapeutic approach and activities in the environment. Such potential mechanisms require additional investigation.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the study. The first is related to the lack of evidence in the field, which made it difficult to recruit participants through municipalities, health practitioners and insurance agencies. As a result, we could not be strict in our recruitment terms, and notices in newspapers and on the university website represented the main recruitment sources. This meant that participants who contacted the university directly already had an interest in the project, which may have been the reason that women were significantly overrepresented in the sample. However, only two participants (one from each treatment) declined to participate after randomisation because they did not want the particular treatment to which they were referred. So, we do not consider prior interest in NBT to be a major bias. The results should nevertheless be regarded as gender-dependent.

Second, there is a relatively low number of participants providing data at all time points in the NNBT group (n = 29) and an even lower number of participants providing data at all time points in the STreSS group (n = 17). The LOCF analysis seeks to compensate for the absence of full data-sets by carrying the last observation forward. A recommendation for future projects is to have fewer time points and more intensive follow-up for participants who do not provide data at all time points and to include more participants in the sample size to account for individuals lost to follow-up.

NNBT was designed to be as individual as possible with minimal interaction between participants even though they were present in the therapy garden at the same time. Interviews with participants in the NNBT group were conducted during the intervention. The results thereof support the conclusion that the participants considered the treatment to be very individual thanks to the therapy form and the garden design.Reference Sidenius, Stigsdotter, Poulsen and Bondas31 However, because of the difference in treatment set-ups between STreSS and NNBT (see supplementary File 3), the NNBT participants could be regarded as clustered as opposed to the STreSS participants. This issue inflicts a major limitation since it was not accounted for in the study design, which also raises the question of how to set-up future study designs entailing a hybrid between individual and group therapy.

There is always the possibility that treatment in groups may result in a correlation of individual responses within a group.Reference Adams, Gulliford, Ukoumunne, Eldridge, Chinn and Campbell32 Therefore, a larger sample size in combination with more groups may have been required in the NNBT arm.Reference Campbell, Fayers and Grimshaw33 In order to make an estimate post hoc as to whether the NNBT treatment in groups resulted in an intracluster effect, the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated on the change in the NNBT participants’ PGWBI scores (before minus after NNBT treatment) (ρ = 0.11). The ICC estimate indicated a lower level of similarity within a group, compared with between groups. One factor explaining the relatively low ICC estimate may be the small number of participants within each group in comparison with the relatively large number of groups (clusters).

Research shows that ICC estimates vary a great deal in secondary care studies,Reference Campbell, Fayers and Grimshaw33, Reference Baldwin, Murray, Shadish, Pals, Holland and Abramowitz34 and it is difficult to say when an ICC can be considered minor. However, even a low ICC estimate may still have a profound design effect, measured as the extent to which a sample size ought to be inflated to accommodate for homogeneity in the clustered data. Based on the post hoc estimate of the ICC and the group size, the design effect was 1.52, leading to an effective sample size of 26 participants for the NNBT treatment.Reference Killip, Mahfoud and Pearce35 Based on the design effect, the required sample size should have been inflated to 61 participants.

Since the research design did not account for clustering, a subsequent clustered analysis would most likely be underpowered since a group RCT requires more groups and much larger sample sizes than an individual RCT.Reference Christie, O'Halloran and Stevenson36 Since the NNBT treatment was considered to be mainly individual, a decision was made to base the statistical analyses on the sample of individuals rather than to take the more conservative approach of using the number of groups as a sample.Reference Donner, Birkett and Buck37 The research design and statistical analysis, therefore, inflicts a limitation on the interpretation of the results in relation to the potential cluster effect in NNBT.

When comparing treatments, there is always the question of how to balance their differences so as to create a ‘fair’ trial that does not favour either treatment. In the present case, we tried to balance as many factors as possible, the most important one being to add more hours to STreSS than is usually provided in CBT. Since STreSS had already proven its efficacy in an RCT studyReference Schröder, Rehfeld, Ørnbøl, Sharpe, Licht and Fink13 and CBT is the recommended approach to treating stress-related illnesses in Denmark,5 we considered it a strong match to NNBT.

In conclusion, the results contribute to the validation of the present NNBT as a treatment equally effective as STreSS for people with stress-related illnesses. NNBT and the garden design may provide research-based guidelines for practitioners, therapists and landscape architects who are working within the field of NBT for people with stress-related illnesses.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.2.

Funding

The project was funded by the TRYG Foundation (grant number 7206-08), a non-profit foundation with core interests in the areas of safety, health and well-being.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.