THE ROOD SCREEN

The rood screen,Footnote 1 an ornately carved and often exquisitely decorated wooden partition, was a near ubiquitous feature of the parish church.Footnote 2 It served an important liturgical function in separating the earthly space of the nave from the sacred realm of the chancel, providing an elaborate frame through which the holy mystery of the Eucharist was witnessed.Footnote 3 In its original form, the rood screen was part of a more complex superstructure incorporating a loft that supported the rood, a large wooden cross displaying the crucified Christ, flanked by the figures of Mary and St John. The west side of the screen, which faced the congregation, was typically richly painted. The lower portion of the screen, or ‘dado’, often depicted a series of painted figurative subjects including saints, prophets, kings and angels. Parclose screens, which separated private chapels from the nave, often adjoined the main rood screen and were also lavishly painted.Footnote 4

With their images of saints, prophets and angels, rood screens and other elements of the rood apparatus fell victim to successive waves of iconoclasm, administered with varying degrees of violence, throughout the Protestant Reformation. During the reigns of Edward vi and Elizabeth i the rood itself was the primary target; rood lofts and screens were largely spared and used as a platform to display the royal coat of arms. However, it was the iconoclasm inflicted during the English civil war, specifically as a response to the Ordinances of 1643 and 1644, that rood screens and their painted images suffered catastrophic levels of damage.Footnote 5 Many screens were dismantled and destroyed, while others were whitewashed or more brutally defaced. The vast majority of screens that survive today are located in East Anglia and the West Country and can be dated to the period of c 1400–1534.Footnote 6 Norfolk has the greatest number of extant screens, around 275, over 100 of which are decorated with painted figures, thus forming the largest body of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century religious painting in England. Footnote 7

DAWSON TURNER AND EXTRA-ILLUSTRATION

Around 1810 Dawson Turner FSA began accumulating prints, engravings and drawings as part of his vast project to extra-illustrate Francis Blomefield’s An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk (1805–10).Footnote 8 The practice of extra-illustration involved the customisation of books with prints, maps and drawings, and resulted in the production of highly prized compilations of immense physical scale and wide intellectual scope.Footnote 9 Dawson Turner’s contribution to the genre was a work of prodigious proportions, including over 7,000 prints and drawings, now bound into fifty volumes and held in the British Library.Footnote 10 It is clear from reading Dawson Turner’s preface to the Catalogue of Engravings, which lists the illustrations produced for the project between 1814–41, that he intended his extra-illustrated Blomefield to act as a means of systematically recording the historical buildings and antiquities of Norfolk that were fast disappearing, due either to neglect or wilful destruction.Footnote 11

It is also evident that Dawson Turner intended the work to act as a platform for showcasing the artistic talents of his family. The traditional accomplishments of young women in the early nineteenth century typically included tuition in painting and drawing, yet the Turner sisters’ artistic training far exceeded this. Their lives were governed by a strict regime that typically saw them drawing or etching in the parlour from half past six in the morning.Footnote 12 Turner’s wife, Mary Dawson Turner (1774–1850), was also an accomplished artist and, coupled with specialist tuition supplied by local artists John Crome (1761–1821) and John Sell Cotman (1782–1842), all of Turner’s daughters developed their considerable artistic talent.Footnote 13 This inherent family skill was exploited by Turner, who wanted to include as many original illustrations in his Blomefield project as possible. For the production of these he relied on the talent and industry of his wife and daughters Maria (1797–1872), Elizabeth (1799–1852), Mary Anne (1803–74), Harriet, Hannah (1808–c 1883) and Eleanor (1811–95), who between them supplied over 4,000 drawings.Footnote 14 From the commencement of the project most of the illustrations were provided by Mrs Turner and her eldest daughters Maria and Elizabeth. After 1823, when Maria and Elizabeth had married and moved away, the responsibility fell to Harriet, Hannah and Mary Anne, who continued to live locally (fig 1).

Fig 1. Harriet Gunn, by Miss H S Turner after Eden Upton Eddis, lithograph c 1838–40 (1840,0208.7). Image: Trustees of the British Museum.

Several authors have acknowledged the significant contribution of Turner’s daughters to their father’s ambitious project, usually to marvel at the sheer quantity of material they produced.Footnote 15 Importantly, Lucy Peltz has emphasised the opportunities extra-illustration presented for female participation in male-dominated arenas, describing the activities of Turner’s household as ‘a domestication of the intellectual sociability of the masculine club’.Footnote 16 There has, however, been very little scholarly interest in the drawings on their own merit.Footnote 17 This has stemmed from the assumption that most of the drawings the sisters produced for the Blomefield project are copies of etchings by John Sell Cotman. The misplaced belief that the sisters merely copied drawings at home incorrectly places them at an experiential and intellectual remove from the historical spaces and objects they drew and undermines the antiquarian value of their work. Charles Bell even suggested that the copies were in fact tracings, stating that he could detect ‘evidence of mechanical devices employed to secure exact resemblance to the originals’, implying there was no artistic skill involved in the sisters’ ability to produce what he termed ‘imitations of deceptive fidelity’.Footnote 18 Jane Knowles has provided a more nuanced account of the Turner sisters’ artistic abilities, but the doubt cast by the proliferation of Cotman copies led her to discount the possibility that Turner’s daughters had created any original drawings for the Blomefield project, stating ‘it is clear that Dawson Turner considered his daughters quite capable of producing images for such a large antiquarian project and so having them create only copies seems rather odd’.Footnote 19 Knowles theorised that, in order to produce original material, Turner’s daughters ‘would have had to travel across Norfolk to sketch in other towns and in the countryside, and this was perhaps considered unsuitable for young women’.Footnote 20

While it is true that many of the exterior and interior views of churches were copies, it is not true of all of them and is certainly not true of Harriet’s drawings of rood screens. Letters from Harriet and Mary Anne to their father written between 1824 and 1850 provide substantial evidence that the women regularly visited local churches specifically to draw rood screens and other fixtures and furnishings from life.Footnote 21 Before discussing these letters in detail, it is valuable to supply a brief history of antiquarian interest in rood screens, to better understand the broader cultural influences that contributed to Turner’s growing fascination with the subject, which is noticeable from the late 1820s and which is evident in Harriet’s drawings from around 1832 onwards.

CHARTING INTEREST IN ROOD SCREENS BEFORE 1830

In the preface to the Catalogue of Engravings, printed in 1841, Turner reminds the reader that ‘several of the objects enumerated in it are no longer in existence. Such is more particularly the case with the stained glass and painted screens’.Footnote 22 As well as bemoaning the physical vulnerability of such objects, Turner voiced his dismay that rood screens had ‘never been made to serve towards the elucidation of the early history of art in England’.Footnote 23 In fact any serious interest in painted rood screens was exceptionally rare before 1830.

The first significant contributor to the history of recording medieval rood screens was the antiquarian draughtsman Jacob Schnebbelie (1760–92), who is particularly notable for showing a precocious interest in this otherwise neglected art form. Schnebbelie had included three hand-coloured etchings of the rood screen at Walpole St Peter, Norfolk, in his publication The Antiquaries Museum (1792), which accompanied a brief description of the screen penned by Richard Gough (1735–1809) (fig 2).Footnote 24 A further coloured plate, depicting part of a rood screen from Grafton Regis, Northamptonshire, was also included in a later number of the same publication, in which Schnebbelie directed his readers’ attention to the abundance of painted rood screens in Norfolk.Footnote 25 Schnebbelie listed nine examples, noting that each screen was ‘in a tolerable state of preservation’.Footnote 26 Dawson Turner included a copy of Schnebbelie’s etchings in his illustrated Blomefield. While he criticised their poor colouring and drawing, he conceded that Schnebbelie was ‘entitled to much praise for having attempted to draw public attention to our Rood-loft Screens’, adding ‘I shall be glad, if my own endeavours to preserve and diffuse the knowledge of them, should be attended with more success’.Footnote 27

Fig 2. Screen at Walpole St Peter, Norfolk, by Jacob Schnebbelie, etching c 1792. Image: Public Domain Mark.

From 1816–18 John Sell Cotman, working under the patronage of Dawson Turner, began producing drawings of rood screens, later published in collected volumes such as Specimens of Norman and Gothic Architecture (1817).Footnote 28 It is important to note that in these early drawings the rood screens are rendered in outline only and the painted images of saints and apostles commonly found on the lower dado are entirely omitted.Footnote 29 The fact that Dawson Turner did not request Cotman to make a visual record of these figurative elements suggests that Turner was interested in rood screens primarily as architectural features at this stage.

It is around this time that Turner’s daughters also start to produce illustrations of rood screens for the Blomefield project. Upon close analysis it is clear that these early drawings have not been made from first-hand observation but rather copied directly from Cotman’s etchings. This may be demonstrated most clearly by comparing Cotman’s etching of Ludham screen (fig 3) and Elizabeth Turner’s drawing of the same subject with a photograph of the real screen in situ (fig 4). It is immediately apparent that Cotman has made a fundamental error in recording the screen’s fenestration. The photograph clearly shows that Ludham screen in fact has three arches either side of the central doorway, not two as Cotman has depicted. Footnote 30 This error lends Cotman’s drawing a unique identifying characteristic that has been dutifully repeated in Elizabeth’s drawing, clearly marking it as a copy of Cotman’s study (fig 5).

Fig 3. Ludham screen by John Sell Cotman, etching c 1816–17 (1870,1008.947). Image: Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig 4. Photograph of Ludham screen by Lucy Wrapson. Image: Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge.

Fig 5. Ludham screen by Elizabeth Turner, drawing c 1818 (BL Add ms 23033 fol 217). Image: British Library Board.

The fact that Dawson Turner was content to collect illustrations of rood screens that did not record their painted decoration suggests that Turner had not yet begun to value them as important specimens of early English painting. By the early 1830s, however, this attitude is seen to change. By examining a further drawing of the screen at Ludham, drawn by Harriet in March 1832, it is clear that she is approaching her subject in an entirely new way (fig 6). First, she has amended Cotman’s fundamental flaw, suggesting that, rather than copying from Cotman’s etching, she has drawn the screen from first-hand observation. Indeed, a letter from Harriet to Dawson Turner dated 16 March 1832, outlining her intention to draw the screen at Ludham, provides the earliest evidence that she had begun travelling to local churches specifically to draw rood screens from life. She reported to her father:

We are first preparing to set off screen hunting at Ludham […] I have now in progress two more drawings from the screen at Stalham and two more from that at Barton – & we shall see what is to be found at Ludham.Footnote 31

Fig 6. Ludham screen by Harriet Gunn, drawing 1832 (BL Add ms 23033 fol 218). Image: British Library Board.

A subsequent letter confirms that Harriet had finished the sketches of Ludham screen and had begun producing a series of drawings of Norfolk screens with her sister Hannah, which included those at Barton Turf, Stalham and Smallburgh.Footnote 32

Harriet’s drawings, executed in full colour, are immediately distinct from Cotman’s earlier monochrome studies. Instead of supplying a single frontal view of the screen, as was the method routinely employed by Cotman, Harriet provides six more closely observed drawings of each pair of figures (fig 7). In choosing to record the figurative subjects in colour, and in abstracting them from the architectural frame of the screen, Harriet’s drawings invite a more focused, aesthetic engagement with the screen’s figurative subject matter. This approach, employed in all of her subsequent screen drawings, accords these paintings a level of attention that was unprecedented at the time. It becomes evident that by 1832 the cultural value of the rood screen, for Turner and Harriet Gunn, had undergone a profound ontological shift whereby it is no longer valued solely as an architectural or liturgical feature but rather as a rare, medieval painted surface.

Fig 7. Detail of Ludham screen by Harriet Gunn, drawing 1832 (BL Add ms 23033 fol 223). Image: British Library Board.

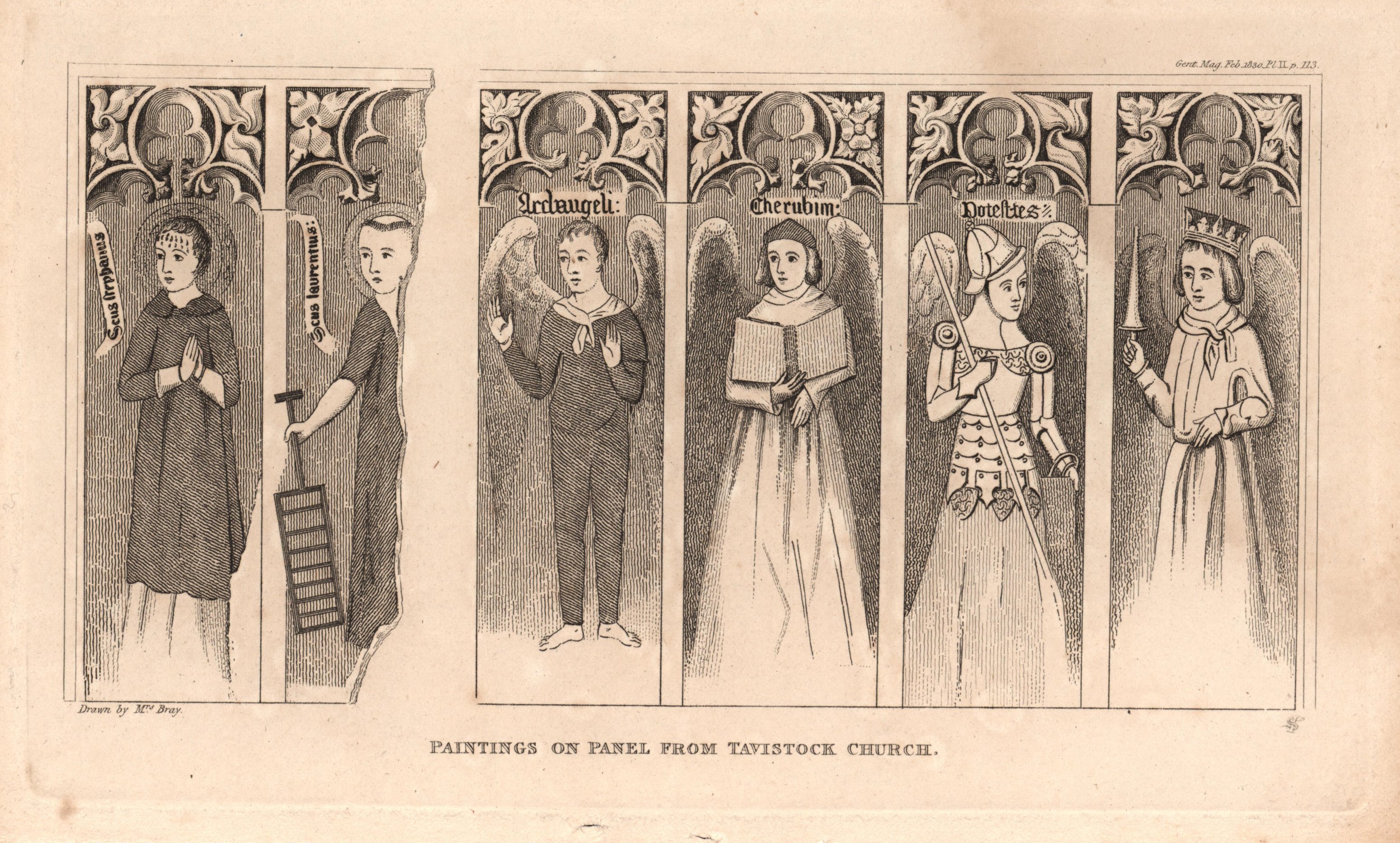

By the early 1830s, an awakening of interest in surviving examples of English medieval painting can be witnessed in wider antiquarian culture. Detailed written descriptions of rood screens began to appear in the Gentleman’s Magazine, such as Alfred Kempe’s (1784–1846) ‘Notices of Tavistock and its Abbey’, which was accompanied by an illustration of the screen from Tavistock church by Anna Eliza Bray (1790–1883) (fig 8).Footnote 33 However, Turner’s appreciation of the rood screen’s cultural value was markedly different from that of his contemporaries. While Kempe’s interest in the Tavistock screen was rooted in its capacity to elucidate the liturgical practices of a bygone age, the appeal of rood screens for Turner lay rather in their potential for illustrating the early history of English painting. Dawson Turner was clearly in a minority in attempting to bestow art historical value on this material, but his motivation for doing so may be better understood if it is considered within the context of concurrent collecting practices and new developments in art historical writing in the 1820s and 1830s.

Fig 8. Figures from Tavistock screen by Anna Eliza Bray, etching c 1830. Image: Devon and Exeter Institution.

TURNER’S TASTE FOR ‘PRIMITIVES’

Turner’s tastes as a collector of paintings have been described by Andrew Moore, and present a man of sound but rather conventional connoisseurship.Footnote 34 Turner’s collection of around fifty paintings featured contemporary British works by John Crome and Thomas Phillips, Dutch landscapes and still lives, Flemish works attributed to Van Dyck and the studio of Rubens, German and French portraiture and genre scenes of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 35 A remarkable addition to the collection was Giovanni Bellini’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with St Peter and St Paul and a Donor, which Turner bought in 1814 when interest in early Renaissance paintings was comparatively rare.Footnote 36 More remarkable still was Turner’s purchase of ten early Italian paintings, latterly known as Primitives, from the engraver, dealer and curator of the Campo Santo, Carlo Lasinio (1759–1838).Footnote 37 These paintings, mostly with spurious attributions, were acquired by Turner in 1826 while on a whistle-stop tour of Italy. The collection comprised fragments removed from larger polyptychs and altarpieces and included two depictions of the Virgin and Child attributed to Cimabue and Orcagna, images of St Thomas Aquinas and St Dominic attributed to Giotto, ‘The Birth of Christ’ attributed to Benozzo Gozzoli and depictions of St Catherine, St Lawrence, St Julian and St Dominic from the altarpiece of San Paolo all’Orto, Pisa, attributed to Taddeo di Bartolo.Footnote 38

Turner’s acquisition of early Italian paintings is likely to have been inspired by a number of influential friendships; first among which is Turner’s acquaintance with Renaissance historian William Roscoe (1753–1831), who began assembling a collection of early Italian paintings at his home in Liverpool from around 1805.Footnote 39 Turner and Roscoe first met each other in 1814 when Roscoe was invited by Thomas William Coke (1754–1842), first Earl of Leicester, to visit the legendary manuscript library at Holkham Hall, Norfolk.Footnote 40 From 1820–28 Turner was involved in Roscoe’s attempt to catalogue and publish the Holkham manuscripts. During this period they formed a strong intellectual bond, and it is apparent that Turner imbibed something of Roscoe’s belief in the didactic potential of early paintings for illustrating the early stages of artistic development. The catalogue Roscoe compiled for the sale of his collection in 1816 confirmed that the majority of the early pictures had been collected ‘chiefly for the purpose of illustrating the rise and progress of the arts in modern times’.Footnote 41 It is surely no coincidence that Turner acquired his Bellini in 1814, the year he met Roscoe, and then augmented his collection with early Italian paintings as his friendship with Roscoe developed.

Turner’s interest in early Italian paintings may also be attributed to his involvement with other London-based intellectual networks. As Caroline Palmer has noted, Carlo Lasinio specialised in the sale of early Italian paintings to ‘a small coterie of enthusiasts for early art’ that included Maria Callcott (1785–1842), Sir Augustus Wall Callcott (1779–1844), Francis Douce (1757–1834), William Young Ottley (1771–1836), Thomas Phillips RA (1770–1845), Charles Lock Eastlake (1793–1865), Turner’s son-in-law Francis Palgrave (1786–1861) and Dawson Turner himself.Footnote 42 Donata Levi suggests that Turner was ahead of his peers in the Callcott circle in his acquisition of early Italian paintings in 1826, but his purchases were undoubtedly guided by their influence.Footnote 43 In 1825 Sir Thomas Phillips wrote to Turner from Italy in praise of Giotto’s frescoes in the Arena chapel.Footnote 44

Turner’s library also boasted a wealth of books and prints that attested to his new-found interest in early schools of painting, such as Lasinio’s engravings of the Campo Santo, Pisa (1806–22), Seroux D’Agincourt’s Histoire de l’Art pars les Monuments (1823) and Luigi Lanzi’s landmark Storia Pittorica dell’ Italia (1795–6), all of which were important in making early Italian painting visually and intellectually accessible to those not resident in Italy. William Young Ottley’s Italian School of Design (1823) and Early Florentine Masters (1826) were particularly influential in expressing a new aesthetic appreciation of early Italian painting, signalling a significant departure from Roscoe’s interest in early painting purely as evidence of the primary stages of artistic development. As Hugh Brigstocke has observed, Ottley challenged engrained assumptions of the supposed technical deficiency of early schools of painting.Footnote 45 Letters exchanged between Ottley and Turner in 1826 display a mutual interest in the works of Cimabue and Giotto and, on the part of Ottley, a desire to capture a permanent visual record of their work that seemed increasingly vulnerable to damage or destruction.Footnote 46

It is significant that Turner acquired his early Italian paintings in 1826, the year he was in contact with Ottley discussing strategies for the preservation of early painting. It is plausible that Turner, inspired by Ottley’s campaign to document the endangered works of the early Italian masters, was also moved around this time to begin recording early English paintings that lay undiscovered on the rood screens of Norfolk. Turner was, however, in a minority as the early works admired by frequenters of the Callcott salon rarely included English medieval painting. Maria Callcott herself was an exception. Having enjoyed access to early Italian and early Northern schools of painting, Callcott had developed a wide-ranging taste for Primitives that extended to English medieval painting.Footnote 47 She had also compiled a detailed description of the progress of English art from the Druids onwards, which unfortunately was never published, and was especially interested in the medieval paintings discovered in St Stephen’s chapel and the Painted Chamber, Westminster, in 1800 and 1818–19 respectively.Footnote 48 As Collier and Palmer have discussed, Maria Callcott’s researches into English medieval painting was remarkable for the period and suggests the influence of the antiquary Francis Douce, with whom she shared many common interests.Footnote 49 Douce, also a close acquaintance of Dawson Turner, had assembled a vast collection of books, manuscripts, prints and drawings reflecting his wide-ranging interests in the ‘the history of arts, manners, customs and superstitions […] of all people in all ages’.Footnote 50 Importantly, Douce was in possession of coloured facsimiles of the murals discovered in the Painted Chamber, produced by Edward Crocker (c 1757–1836) in 1820, and it is likely that these images had not only stimulated Maria Callcott’s interests but also encouraged Dawson Turner in his drive to capture a visual record of Norfolk screens.Footnote 51 However, this was not a fascination shared by many others in the Callcott circle.Footnote 52 Eastlake considered English medieval painting to be irrelevant as, in his opinion, it did not contribute sufficiently to the history of figurative painting.Footnote 53 The abundance of figurative work extant on Norfolk screens was seemingly unknown to Eastlake, confirming that rood screens remained all but invisible to those who might be persuaded to appreciate their art historical value. If Turner was to bring this neglected branch of medieval painting within the visual and intellectual scope of art history, the production of colour facsimiles was vital in achieving this end.

HARRIET GUNN AND THE CAPTURE OF ENGLISH MEDIEVAL PAINTING

In 1830 Harriet Turner married the Revd John Gunn, vicar of Barton Turf, Norfolk. Gunn had developed a reputation locally as a knowledgeable antiquarian with a specialist interest in medieval painting, and it is clear that the marriage, through Gunn’s encouragement, facilitated Harriet’s access to her subject of study. Letters from Harriet and Mary Anne to their father, written between 1824 and 1850, are particularly valuable in illuminating how the sisters engaged physically, visually and intellectually with the material they drew, revealing the difficulty of travelling to remote churches and the painstaking work of recording the largest, most complex screens. From her numerous accounts of visiting churches it is clear that Harriet possessed a sophisticated understanding of the orders and elements of Gothic architecture. She delighted in providing detailed descriptions of church interiors, monuments, fixtures, furnishings and screens, which were then captured in watercolour for the Blomefield project.

The earliest written evidence confirms that Harriet had drawn the screens at Barton Turf, Stalham, Smallburgh and Ludham in 1832.Footnote 54 By 1833 it appears that she had achieved some notoriety as a rood screen specialist. In a letter to William Gunn (Harriet’s father-in-law), John Sell Cotman described the screen in Attleborough church, remarking ‘I do not recollect having seen it figured in Mr Turner’s Blomfield [sic], if he has it not tis a lion worthy of his menagerie’ and recommended the screen as ‘a fine opportunity for Mrs John Gunn to exercise her talent in an Aaron and a Moses’.Footnote 55 In the same year Harriet had drawn the screen at Paston, and in 1834 had recorded those at Worstead and Aylsham. Other largescale screens recorded by Harriet include those at Belaugh (1837), Ranworth (1839), Sparham (1841), Irstead (1842), Tunstead (1841–43) and North Walsham (1844). Both Mary Anne and Hannah contributed to the tally, drawing those at Filby (1840) and Thornham (1842) respectively.

The letters reveal that such forays into antiquarian discovery frequently placed Turner’s daughters at a distinct advantage to their father, providing them with privileged knowledge of new discoveries. Harriet was particularly keen to relay her encounters with screens that she found especially noteworthy, such as Worstead, which Harriet described in a letter to her father in July 1834:

We were at Worstead church all Saturday from 11am to 7pm & a most beautiful though elaborate subject it is that we have in hand by far the most beautiful of any screen I ever drew. In a later & much more elegant style than any. The figures remind me in the whole of their design & art of Pietro Perugino.Footnote 56

By 1834, when Harriet had drawn the screen at Worstead, she was sufficiently experienced to be able to discern its aesthetic superiority to the screens she had seen thus far. Her observation that the figures reminded her of the work of Pietro Perugino (c 1450–1523) is significant, reflecting her familiarity with current trends in art historiography and her confidence in applying this knowledge to the critique of early English painting. At the time, Perugino was regarded as an early Italian master, of the sort that was beginning to command increased attention in German art historical writing. Authors such as Karl Friedrich von Rumohr (1785–1843), Johann David Passavant (1787–1861), Franz Kugler (1808–58) and Gustav Friedrich Waagen (1797–1868) all accorded a new prominence to early Italian paintings and, as the tutor of Raphael, Perugino was a subject of special interest. As a fluent German speaker, Dawson Turner, along with other members of the Callcott circle, was influenced by these developments, as may be evidenced by his acquisition in 1826 of the ten early Italian paintings discussed above.Footnote 57 Harriet’s cousin Elizabeth Rigby (1809–93), later Lady Eastlake, had produced an English translation of Passavant’s Tour of a German Artist in England in 1836, a project that Turner had encouraged her to complete.Footnote 58 Harriet was then positioned within a familial and social network where German art historical scholarship was routinely discussed, and it is apparent that she is applying the main tenets of these debates to aid her aesthetic appreciation of painted rood screens in the late 1830s.

These opinions are particularly fascinating, as any form of focused critical response to English medieval painting is extremely rare at this time; rarer still are accounts of women’s engagement with this material.Footnote 59 Harriet’s letters are particularly rich in this capacity, often providing unexpectedly detailed accounts of her aesthetic and intellectual response to the screens she recorded. This is perhaps most evident in her appraisal of the screen at Ranworth, which Harriet visited on four separate occasions with her sister Hannah in April 1839. Hannah reported to her father:

Harriet told you in her last letter of our very interesting day at Randworth [sic] on Wednesday, since that time we have been busily employed in putting together our sketches & bringing them into a state to be usable for tracings.Footnote 60

The task of turning the sketches into final drawings was a lengthy process. Harriet produced around fifty drawings of this large screen and its parclose screens, which she finally completed at the close of January 1840.Footnote 61

It is difficult to envision exactly how the Ranworth screen would have appeared to Harriet and Hannah when they saw it in April 1839. A drawing by Mary Anne titled ‘Interior of Ranworth looking East’, dated 1840 and depicting an unidentified figure seemingly in the act of sketching, provides useful evidence of the church’s general appearance at the time (fig 9).Footnote 62 The rood loft remains intact with the coat of arms displayed in the centre. The screen’s painted figures are also clearly indicated, yet it is impossible to gain an accurate sense of their physical state of preservation. Conservation reports by Pauline Plummer confirm the screen had suffered from repeated episodes of iconoclastic mutilation and a particularly disastrous ‘restoration’, which had stripped away significant areas of original paint to expose the under-drawing beneath.Footnote 63 Despite this damage, Ranworth is now widely recognised as one of the finest examples of rood screen painting.

Fig 9. Interior of Ranworth church by Mary Anne Turner, drawing 1840 (BL Add ms 23042 fol 10). Image: British Library Board.

Both Harriet and Hannah saw the screen at a time when few people knew of its existence and yet were able to appreciate its technical and aesthetic superiority based on their own first-hand encounters with numerous local examples. In sentiments that echoed Ottley’s criteria for judging the merit of early Italian paintings, Hannah observed ‘the painting of some of the heads in the side screens is really beautiful, the attitude[s] very varied, & the countenances full of individual expression’.Footnote 64 This was endorsed by Harriet, who reported to her father:

So fine a screen as that at Randworth [sic] I certainly never saw […] both in point of art, of richness of original colour […] & of delicacy of execution & detail, it is far superior to any other that I was so fortunate as to see. The whole style of its design must be of considerably later date, than that of Norfolk screens in general.Footnote 65

Through the comparison of key stylistic details such as richness of colour, the naturalistic treatment of drapery and the graceful deportment of figures, Harriet believed the Ranworth screen to be of a much later date than others she had seen. The superior figure painting evident on the north and south parclose screens led her to speculate that they were painted by different artists from those responsible for the more ‘commonplace’ central screen (fig 10).Footnote 66

I hardly know whether I am right, but on this the third day devoted to that screen, & the third time that I have examined & tried to copy it, I should say that it seems to me that the middle & two side screens […] were certainly painted by different hands, & at different periods – The middle one is a much more commonplace thing than those in the side-aisles, & of rougher workmanship, & less graceful style.Footnote 67

Fig 10. St Michael, from the south parclose at Ranworth by Harriet Gunn, drawing 1839 (BL Add ms 23042 fol 54). Image: British Library Board.

The issue of the screen’s authorship was a matter of some debate between the sisters. Harriet joked to her father that she was afraid that Hannah ‘was about to broach some heretical doctrines of her own as to the screen at Randworth [sic], & as to its being the work of more hands than one, which I maintained, & she disputed’.Footnote 68 Such statements reveal Harriet’s confidence in the veracity of her own judgement. However, her conclusions are based on more than aesthetic or stylistic comparison alone. She continued:

There is no indentation evident in the diapering here, nor any stamping, if I may so call it, but the working on the gold is produced by the scoring it over with fine black lines, thus [she includes a small sketch here to exemplify the technique]. In most cases, the points of a diadem, or nimbus, or folds of drapery, would be marked with deep furrows, so that the shadows cast by the graver would distinctly mark every division but in this screen the lines are delicately traced with a pen or brush filled with some black & glossy ‘pigment’.Footnote 69

Harriet notices that the screen’s decorative background (diapering) has been achieved through a different process from that which she has seen elsewhere. Instead of the more familiar technique of cast-relief or pastiglia, which Harriet refers to as ‘stamping’, at Ranworth the decorative embellishment has instead been applied with a brush.Footnote 70 Such observations demonstrate Harriet’s close scrutiny of the screen’s technical characteristics and testify to her increasingly analytical appreciation of this genre of painting.

To an extent, Harriet’s observations are corroborated by the latest technical analyses of Ranworth screen carried out by conservator Lucy Wrapson.Footnote 71 Harriet’s appreciation of the screen’s extraordinary richness of colour is supported by Wrapson’s analysis of paint samples, which confirms the Ranworth painters used the widest range of pigments found on any East Anglian screen.Footnote 72 Wrapson’s study also recognises the use of black painted detail over silver and gold leaf, to distinguish the most precious elements of the painting, such as saintly attributes and brocaded fabrics.Footnote 73 However, Harriet’s fascination with the technical and aesthetic superiority of the Ranworth screen misled her into believing it must be of a later date than others she had seen. Ranworth can be confidently dated to c 1479–80, which is concurrent with Barton Turf (1480) but earlier than those at Ludham (1493), Aylsham (1507) and Worstead (1512).Footnote 74 Harriet had also correctly detected the hand of several different artists at Ranworth; however, her belief that the technically superior ‘side screens’ were completed at a later date than the centre screen, and by different artists, is overly simplistic. It is widely agreed that the workshop responsible for Ranworth was in operation between 1470 and 1500 and that the screen and parcloses were painted in stages between these dates, as funds permitted, probably by two generations of artists from the same workshop.Footnote 75

It is clear from these excerpts that Harriet is beginning to apply increasingly sophisticated methods of technical and stylistic analysis to aid her appraisal of the screens at Worstead and Ranworth. In so doing, she affords these paintings a degree of aesthetic and critical attention they had previously been denied. It is also apparent that her understanding of this material is enriched by the intellectual and social mechanics of the familial network in which she is immersed, seen in the use of current art historical theories to underpin her critique of painted screens and in her desire to communicate and debate these ideas with her father and sisters.

As time went on and the Blomefield project progressed it is clear that Harriet came to rely more heavily on the support of her sisters to enable her to record the more challenging screens. This is particularly evident with that at Tunstead, which Harriet had been attempting to draw from January 1843. By September she had made little progress and lamented to her father: ‘Tunstead screen is so utterly disheartening, the work of it so overpowering […] I have been to look at it many times, intending to set about it, & come away without a stroke.’Footnote 76 Harriet petitioned her father for extra help, imploring:

[If] you would let me keep dear Mary for a few days, we would take the screen by storm, assailing it in three quarters at once – & with Mary to [draw] the faces, we might hope to [avoid], what Liz and I should surely find, if alone, certain & irrecoverable defeat […] [if] we have Mary we will Venire, Videre, Vincere the screen.Footnote 77

Harriet light-heartedly adopts the militaristic language of conquest, used here as a rallying-cry to muster reinforcements in the hope of vanquishing a particularly obdurate foe. It is clear that she is galvanised by the support of her sisters as they pool their individual skills to ‘capture’ their subject, in every sense of the word. Such statements give a vivid impression of the sisters’ collaborative working methods, which became a distinct and highly effective characteristic of their antiquarian agency.

Indeed, the Turner sisters’ collective engagement with the material remains of the past often resulted in thrilling discoveries. In the summer of 1845 John Gunn, in his capacity as vicar of Barton Turf, had removed some pews that were obscuring part of the rood screen. In September Mary Anne travelled to Barton Turf to inspect the work, which, in turn, occasioned an unexpected discovery. Mary Anne’s eagle eye detected the remnants of a previously hidden parclose screen, the revelation of which she excitedly reported to her father:

By the removal of pews, the whole of the centre screen now remains open, & the figures look most beautiful […] But as we stood admiring them I spied the edge of an ermine robe beneath the pannels [sic] of modern deal which covered the wooden division that separated St Thomas’s chapel from the church. And soon hammers and chisels were in requisition […] The boards were quickly ripped off, and underneath there stood looking out into the light from which they had been debarred for perhaps 300 years, the figures of the four sainted kings of England.Footnote 78

The circumstances of the find are revealing, first, in confirming that the sisters not only recorded, studied and discussed rood screens but also played an active role in their discovery (fig 11). It is also notable that the excitement with which the new screen was met was not in evidence when a previously hidden wall painting was discovered in the same church a few months earlier. The painting, which represented ‘The Reward of Sin’ and depicted naked figures being driven into the jaws of Hell, lasted barely three months before being re-concealed beneath a fresh coat of whitewash. Harriet expressed her shame at the outcome, but justified the decision claiming that the painting represented ‘the worst style of art possible’ being ‘bad in drawing, bad in conception, & very bad in execution’ (fig 12).Footnote 79 The fact that Harriet had made a copy of the painting before its obliteration served as justification that it had been ‘preserved’ in some way for posterity. The same fate befell the wall paintings discovered in Crostwight church in 1847, again recorded by Harriet in a series of drawings later published in Norfolk Archaeology in 1849.Footnote 80

Fig 11. Edward the Confessor, from the parclose screen at Barton Turf by Harriet Gunn, drawing 1845 (BL Add ms 23025 fol 25). Image: British Library Board.

Fig 12. Wall painting in Barton Turf church by Harriet Gunn, drawing 1845 (BL Add ms 23025 fol 14). Image: British Library Board.

Such regrettable outcomes exposed the double standards at play regarding the preservation and appreciation of English medieval painting. It was evident in the actions of Gunn and Turner (who had also condoned the re-covering of the Crostwight murals) that English medieval painting was ranked in a hierarchy in which the rood screen assumed a position of greater importance.Footnote 81 However, for all the emphasis on the undeniable artistic and technical merit of Norfolk screens such as those at Ranworth and Worstead, they remained shrouded in obscurity. By the mid-1840s, with the creation of the British Archaeological Association (1843, BAA) and the Archaeological Institute (1844), rood screens would, with the aid of Harriet’s drawings, at last become known to a wider audience.

DISSEMINATING KNOWLEDGE OF ROOD SCREENS IN THE 1840S

Bank House, Turner’s domestic residence in Yarmouth, was a primary locus of intellectual exchange that received a coterie of distinguished visitors.Footnote 82 It was within this erudite environment that Turner’s Blomefield project gained its reputation as an encyclopaedic record of Norfolk’s cultural heritage and where the drawings produced by Harriet and her sisters were disseminated among Turner’s intellectual network.

One such acquaintance was the Revd Richard Hart, who, on 14 March 1844, delivered a lecture at the Norwich Museum on the antiquities of Norfolk.Footnote 83 On the subject of Norfolk’s painted rood screens, Hart admitted that he was indebted to Dawson Turner for almost everything he knew on the subject.Footnote 84 Hart’s lecture is valuable in providing a synopsis of the state of knowledge regarding rood screens in the mid-1840s, based predominantly on Turner’s own observations and opinions. Hart reported, quoting Turner, that the work of at least eleven different artists’ hands of varying merit could be detected across the range of Norfolk screens, with ‘three or four different artists hands evident on the same screen’.Footnote 85 This point immediately recalls Harriet’s own observations of the screen at Ranworth, discussed above, in which she detected the hand of at least two different artists. Perhaps most revealing is the insight Hart’s lecture provides into the understanding of the materials, techniques and processes used in screen production. Hart reports:

They appear to have used a sort of distemper or body colour, employing chalk as their medium; but a few of them, I believe, are painted in oils. In some instances, which I have seen, the gold diaper in the background has been evidently stamped with an instrument rising considerably above the painted surface or laid over a plaster composition so stamped.Footnote 86

Again, these observations suggest that a detailed level of analysis had taken place in order to establish the use of oil-based media, which was far more widespread than Hart suggests.Footnote 87 It is not specified how Turner and Hart had reached this conclusion, but, as Nadolny states, research into the use of oil paint in English medieval painting had become a highly divisive subject by the 1840s.Footnote 88 The debate intensified around 1802 when the historian and engraver John Thomas Smith (1736–1833) commissioned the chemist John Haslam (1764–1844) to undertake tests on samples taken from the newly discovered murals in St Stephen’s chapel executed c 1351–60. Haslam concluded the paintings had been executed entirely in an oil-based medium, and this evidence was augmented further when Smith discovered numerous references to the purchase of painters’ oil in the Westminster account rolls.Footnote 89 Smith published his findings in Antiquities of Westminster in 1807, a copy of which graced the shelves of Turner’s library. It is likely this work was influential in various ways in the Turner household, both in advancing new theories of the early use of oil-based media, and as a vehicle for illustrating and promoting English medieval painting via Smith’s exquisite hand-coloured images.Footnote 90 It was not until the 1840s that Smith’s theories were more vehemently contested by John Gage Rokewood (1786–1842) in a paper addressed to the Society of Antiquaries in 1842.Footnote 91 Gage Rokewood was adamant that oil painting was only ever used in a medieval context ‘for the mere purposes of house painting or decorating’.Footnote 92 Therefore, for Turner and Hart to confidently state in 1844 that rood screens had been painted in oil was to broach heavily contested ground.

Hart’s interest in the use of cast-relief decoration for the creation of diapered backgrounds, which he described as ‘stamped’, again recalls Harriet’s observation of the treatment of diapered backgrounds on the Ranworth screen.Footnote 93 Hart was referring to a different example in which the use of raised cast-relief decoration was clearly apparent. By contrast, Harriet had commented on the conspicuous absence of this technique at Ranworth. One can only speculate on the extent to which Harriet’s unique understanding of screens gained from close scrutiny had contributed to Turner’s, and subsequently Hart’s, enhanced understanding of the subject. It must be borne in mind that Harriet’s theories regarding authorship and technique had been communicated to Dawson Turner five years prior to Hart’s lecture and provide some of the earliest recorded aesthetic and technical observations of rood screens. Harriet’s observations must therefore be viewed as forming the foundations of scholarship in this area.

It is undeniable that Harriet’s drawings permitted the wider dissemination of Hart’s scholarship in other fields. Hart used a lithograph of Harriet’s drawing of a bishop from the south parclose at Ranworth to illustrate his paper discussing the components of medieval ecclesiastical vestments (fig 13).Footnote 94 This scientific re-purposing of the medieval image places it within a new discursive formation and redefines its value as visual data from which useful knowledge may be derived. This was characteristic of the rhetoric used in the early 1840s by the founders of the BAA, who wished to distinguish the ‘practical purpose’ of the new discipline of archaeology. As Albert Way had claimed, archaeology ‘would enter into a wider field of active research than that to which the exertions of the Society of Antiquaries have hitherto been directed’.Footnote 95 Dawson Turner and John Gunn were enthusiastic advocates of the new scientific rigour archaeology proposed and were also keen to find a more sympathetic platform for their own specialist researches. Both Turner and Gunn joined the BAA in 1843, but subsequently defected to the rival Archaeological Institute in 1844.

Fig 13. Bishop from the south parclose at Ranworth by Harriet Gunn, drawing 1839 (BL Add ms 23042 fol 51). Image: British Library Board.

Gunn attended the first annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute in Winchester in 1845, a novel feature of which was a temporary museum with exhibits arranged into roughly chronological categories. In the section dedicated to Roman antiquities, Gunn exhibited some ‘fragments of “Samian” ware and a cinerary urn found at Caistor, Norfolk’.Footnote 96 Notably, in the section devoted to ‘Works of Art and Drawings’, Gunn also exhibited a selection of ‘Drawings beautifully illuminated in colours by Mrs. Gunn, representing paintings which decorate the wooden screen of Tunstead church, Norfolk’.Footnote 97 Situated among the illustrated remnants of wall paintings, tiles and maps from Winchester, Westminster Abbey and St Alban’s, it is clear that the temporary museum provided a prestigious public platform from which Norfolk’s painted rood screens could be displayed to a wider audience and so stake a tentative claim to national importance.

Capitalising on the evident zeal for archaeological enquiry into antiquities, Dawson Turner and his business partner Hudson Gurney (1775–1864) were instrumental in founding the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society (NNAS) in 1846. Both Turner and Gurney served as vice presidents of the NNAS from 1846 until their respective deaths in 1858 and 1864. It is via the machinery of this organisation that Harriet’s work contributed most forcibly to the production and dissemination of specialist knowledge of medieval painting. At the Society’s monthly meeting on 6 May 1846 Dawson Turner exhibited Harriet’s drawings of ‘Mural paintings lately discovered in Catfield Church; together with two drawings of the interior of the church to show their position and arrangement’.Footnote 98 Turner also exhibited ‘a series of drawings of the Church at Ranworth […] in reference to the very elegant Rood-screen still remaining there’.Footnote 99 A lithographic print of Harriet’s drawing of a bishop from the parclose at Ranworth was featured in the first edition of Norfolk Archaeology to illustrate Hart’s paper on ecclesiastical vestments, as discussed above (fig 14).Footnote 100

Fig 14. Bishop from the south parclose at Ranworth after a drawing by Harriet Gunn, used to illustrate Revd Hart’s paper published in Norfolk Archaeology, lithographic print c 1840 (BL Add ms 23042 fol 52). Image: British Library Board.

It was the occasion of the Royal Archaeological Institute’s annual congress, held in Norwich in 1847, that provided the most significant public display of Harriet’s drawings. The occasion presented a golden opportunity for Turner, a member of the organising committee, to promote his own interests and to showcase the talents of his daughter Harriet. At the meeting of the Architectural section of the institute, ‘drawings from the skilful pencil of Mrs. Gunn’ were used to illustrate a paper on early ecclesiastical architecture in Norfolk, read by John Gunn.Footnote 101 In addition, in the temporary museum assembled at the Swan Hotel, Norwich, Dawson Turner exhibited:

A series of fifty-two exquisitely illuminated drawings by Mrs. Gunn, representing the decorations of the painted screen-work in Randworth [sic] church, Norfolk, and exhibiting most curious figures of Apostles, saints, and martyrs.Footnote 102

This was accompanied by a further display described in the catalogue as ‘Drawings beautifully executed by Mrs. Gunn, representing a remarkable figure of St. Walstan, […] depicted on the screen at Ludham, Norfolk’.Footnote 103 From these examples it is possible to gather that Harriet exhibited well in excess of sixty drawings.

Importantly, the material exhibited at the 1847 congress represented one of the largest displays of English medieval painting assembled at any of the annual congresses held thus far. Paintings under discussion included the recently discovered Norwich Retable, while those on display included panels from the parclose screen at Barton Turf (discovered by Mary Anne in 1845) and paintings loaned by Norfolk-based collectors including ‘an ancient painting on panel from Loddon church’, ‘portraits of Antoine de Boileau and his wife’, ‘a painting on panel from St John’s Maddermarket and ‘an hexagonal music stand curiously ornamented with paintings’.Footnote 104 The event attracted some of the most eminent specialists in medieval painting, including John Britton (1771–1857), Albert Way (1805–74) and Matthew Digby Wyatt (1820–77). It is significant that Harriet’s illustrations of painted rood screens were displayed in this august environment alongside the work of established antiquarian draughtsmen, such as Henry Shaw (1800–73) and Orlando Jewitt (1799–1869), and where the latest theories regarding English medieval artistic production were under discussion. Albert Way, in his paper ‘Extracts from the account rolls of Norwich Priory’, hoped the information presented would ‘assume some interest in connection with the early development of the arts in these kingdoms’ and specifically credited ‘the exquisite drawings of the rood screens […] contributed to our Museum by the kindness of Mr Dawson Turner’ as extending knowledge in this area.Footnote 105 Albert Way reiterated this sentiment in the Archaeological Journal, stating:

The gorgeous rood-screens and mural paintings which abound in East Anglia, possess a value, in connexion [sic] with the history of art, which has happily been long since appreciated by that distinguished and indefatigable archaeologist, Mr. Dawson Turner. We are indebted to him, and to the skilful pencil of more than one fair coadjutor of his extensive research in subjects of this nature, for some of the most attractive and valuable contributions to these volumes.Footnote 106

It is regrettable that the ‘fair coadjutors’ remained anonymous, but it is clear that Way understood Turner’s position as an authority on rood screens would have been impossible without the documentary evidence supplied by Harriet’s drawings. Harriet’s work had therefore claimed the attention and praise of those at the forefront of research into English medieval painting and continued to appear in antiquarian and archaeological contexts. In 1848 Dawson Turner exhibited two sets of drawings to the Society of Antiquaries, illustrating the ‘frescoes, paintings, and other ancient remains from the churches of Gateley and Crostwight’, and three anastatic prints of Harriet’s drawings of the Crostwight murals featured in the second volume of Norfolk Archaeology.Footnote 107

By the late 1840s, however, Harriet’s drawings of rood screens would have appeared anachronistic. With the growth of the ecclesiology movement, the re-instatement of chancel screens in churches and cathedrals created its own liturgical controversy. The Cambridge Camden Society (established 1839) particularly advocated the central theological role of the rood screen in separating the ‘Church Militant’ (the laity) from the ‘Church Triumphant’ (the clergy) and saw the screen as vital in achieving ‘ritualistic propriety’.Footnote 108 Such ideas bore an uncomfortable resemblance to A W N Pugin’s equally contentious re-introduction of the chancel, screen and rood into his new designs for Catholic churches. Therefore, to promote the rood screen as an essential feature of the ‘ideal’ Anglican church provoked widespread fear among Anglican clergy of an unwelcome return to ‘Popish’ modes of worship.Footnote 109 While the re-introduction of rood screens was angrily contested, these developments also created a demand for archaeologically accurate drawings of medieval screens that might serve as models for new designs.Footnote 110 Publications such as E L Blackburne’s Decorative Painting Applied to English Architecture during the Middle Ages (1847) and J K Colling’s Gothic Ornament (1848–50) featured overtly technical illustrations of rood screens and provided exquisitely rendered pattern books from which the architect/designer might reliably copy.Footnote 111 In comparison, Harriet’s drawings appeared naïve, inaccurate and unsuited to the transfer of practical knowledge.

By 1848 Harriet appears to have stepped away from the Blomefield project altogether, with the bulk of the drawings provided instead by Yarmouth-based artist C J W Winter. Winter’s richly coloured illustrations of rood screens are distinctive in their minutely observed detail and immediately call into question the veracity of Harriet’s earlier drawings (fig 15). Winter continued working on the Blomefield project until Turner’s death in 1858 and maintained his position as one of Norfolk’s favoured antiquarian illustrators.

Fig 15. Painted screen at Ranworth by C J W Winter, watercolour c 1865 (NWHCM:1951.235.B8). Image: Norwich Castle Museum, Norfolk Museums Service.

In 1865 the NNAS decided to produce a series of publications promoting the county’s rood screens. Limited funds dictated that only three volumes were published dedicated to the screens at Ranworth (1867), Barton Turf (1869) and Fritton (1872), with the illustrations, again supplied by Winter, executed mainly as monochrome outline drawings (fig 16). John Gunn supplied the letterpress for the Barton Turf publication and continued to argue for the art historical importance of Norfolk’s rood screens, but the focus had now returned to establishing whether the paintings had been executed in oil-based media.Footnote 112 The preoccupation with media may be seen as a rebuttal against Charles Eastlake’s publication Materials for a History of Oil Painting (1847), which reiterated Gage Rokewood’s view that oil paint had only ever been employed in a decorative capacity in English medieval art.Footnote 113 The evidence supplied by Norfolk’s rood screens contradicted this theory, but it was difficult to argue against Eastlake who, as keeper and later director of the National Gallery, became the dominant voice of institutional art history in the mid-nineteenth century.

Fig 16. Figures from the rood screen at Barton Turf by C J W Winter, lithograph c 1869 (NWHCM:1954.138.Todd24.Tunstead16). Image: Norwich Castle Museum, Norfolk Museums Service.

When considered in this context, the work of Dawson Turner, Harriet and John Gunn should be acknowledged as pioneering activity, which brought the importance of Norfolk’s rood screens to wider attention and laid the foundations for continued scholarship in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. However, it is only with the scientific evidence supplied by technical art history in the twenty-first century that the enduring theories of Eastlake would finally be disproved, and the true art historical value of Norfolk’s rood screens revealed.Footnote 114

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research for this paper was enabled by a travel grant awarded by the Paul Mellon Centre.

I would like to thank the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, for permission to quote from material held in the Dawson Turner archive. I am indebted to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which have greatly improved this paper. I also thank Wayne Kett at Norwich Castle Museum and extend my gratitude to Dr Lucy Wrapson for sharing her vast knowledge of painted rood screens with me.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- BAA

-

British Archaeological Association

- BL

-

British Library, London

- TCC

-

Trinity College, Cambridge

- NNAS

-

Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society

- NWHCM

-

Norfolk Museums Collections

- SDKA

-

Sidney Decimus Kitson Archive, Leeds City Art Gallery