A. Introduction

Desperate refugees sailing towards the old continent serve as a sad reminder of the salience of being inside or outside the EU, and of the moral judgment involved in including and excluding.Footnote 1 Even more topical, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the temporary closure of many intra-EU borders, while export restrictions on vaccines show the importance of the EU’s external borders. These observations illustrate the broader theme of the present Article, which traces the development of a supranational conception of territorial rule. The crucial question is how geographical space relates to normative rule in the EU. Quite a few recent ECJ judgments touch on territorial aspects of EU rule, such as EU law’s relationship to border disputes between Member States,Footnote 2 the reach of territorial sovereignty and public order as a defense against EU law obligations,Footnote 3 how the territorial extension of EU law to EFTA-States affects the extradition regime under the European Arrest Warrant,Footnote 4 and how EU law protects EU citizens’ personal data in case private companies transfer it to third countries.Footnote 5 In light of these scattered manifestations of territorial elements in the EU’s authority claim, I use insights from EU law, political theory, and political geography to shed light on the EU’s territorial claims. These insights help us understand better how the EU governs. More importantly, the EU’s territorial claims raise various legitimacy challenges that call for developing a proper theoretical framework.

This Article proceeds as follows. Section B highlights the importance of territoriality for the exercise of political authority and explains why state territoriality does not conceptually exhaust the notion of territorial rule. Thereafter, Section C will primarily focus on how EU law affects the territorial rule of Member States before paying more attention to the development of territorial elements on the supranational level in Section D. Section E will review the role of EU citizens, and Section F will discuss various functional elements in the evolving picture of the EU’s conception of territoriality, followed by a summary in Section G. Finally, Section H concludes that the EU’s territorial claims call for developing a proper theoretical framework in order to evaluate their legitimacy.

B. The Conceptual Space for Territoriality Beyond the State

A fundamental distinction between territorial and functional rule frequently reflects the underlying duality of statist and international governance models. In essence, bounded territorial rule represents the post-Westphalian domain of states.Footnote 6 Limited functional governance, by contrast, characterizes traditional international organizations. To locate the EU on this spectrum, I want to begin by liberating the notion of territoriality itself from its statist straitjacket. That implies, first, that we know what state territoriality looks like.

The pedigree of internal and external state sovereignty is to claim and uphold ultimate authority over a given territory. These two dimensions characterize the state’s internal superiority over other authorities and its efforts to shield its territory from external influence. This is how we understand territoriality, namely the characteristically strong relationship between people, place, and political institutions in states. Post-Westphalian sovereignty is necessarily and intrinsically spatial because the state’s territory circumscribes the legitimate realm of its political power.Footnote 7 To illustrate, in David Miller’s conceptualization, states claim a tripartite form of territorial rights, namely the right to jurisdiction, the right to use the territory’s resources, and the right to control borders.Footnote 8 The conceptual link between states and territoriality seems so strong that an influential view in political theory views territory as the property of, or even identical to, the state.Footnote 9 One can be forgiven, then, for assuming that the very idea of territorial rule is limited to nation states.

Yet, the paradigm behind territorial nation-statehood itself is historically contingent. Because territoriality represents a governance tool—serving to the end of governing discrete societies—it has always been open for various manifestations of territorial rule, for example in empires or federal systems.Footnote 10 In his impressive study, The Birth of Territory, Stuart Elden traces the role of territoriality in conceptualizing political authority since the early days of the Greek polis. He concludes that territoriality is highly contingent on the historical, geographic, and political-economic background conditions.Footnote 11 Therefore, it is hardly surprising that current developments, especially globalization, challenge the very idea of territoriality almost as much as they test state sovereignty itself.Footnote 12 Thus, from a historical point of view, there is no reason to assume that only States may develop territorial rule.

Conceptually, moreover, state territorial rule does not exhaust the notion of territoriality, although states surely represent its strongest contemporary manifestation. Territoriality expresses a normative relationship between humans, a distinct patch of the earth, and how political institutions administer it. Territorial rule, or territoriality, articulates the idea of administering a bordered space. It represents a generic governance tool that links a geographic place, the people who live there, and the exercise of normative power. In short, territoriality is a function with three components: People, place, and power. The intention to exert normative control transforms a mere spatial area into an important component of political authority.Footnote 13 One of the main elements of territorial rule is jurisdictional authority defined by geographical criteria, otherwise known as territorial jurisdiction. This notion implies that the mere fact that a measure has effects on a given territory suffices to trigger the application of a given legal order. While territorial jurisdiction is first and foremost a feature of state authority, we will see below how the ECJ and the EU legislator use a similar mechanism to trigger the application of EU law.

To summarize, there is room for territoriality in governing supra-state polities. Both historically and conceptually, the notion of territoriality permits a non-state polity, such as the EU, to develop its own notion of territorial rule. Territoriality helps to explain the various elements in the EU’s authority claim, to which this Article turns to next. The main aim of the following reflections is to uncover the EU’s conception of territoriality, understood as distinctly supranational relationship between place, people(s), and power. That is the necessary groundwork for evaluating the legitimacy of these territorial claims.

C. The Reflexive Relationship Between EU Law and National Territory

The starting point of this Article was a reflection on the link between State sovereignty and territoriality. Therefore, it seems only natural to begin the examination of the EU’s territorial claims with a study of how it affects state territoriality. To put it broadly, how does the EU’s geographical territory relate to the territory of the Member States? The idea of EU territory itself derives from and remains parasitic on national territory. Prominent features of the EU’s governance have profound effects on core elements of the national territorial rule and transform the very idea of state territoriality. The relationship between national and European territorial rule is thus reflexive.

I. The EU’s “Parasitic” Territory

Article 52 of the Treaty on European Union (“TEU”) and Article 355 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) [hereinafter The Treaties], respectively, provide the natural starting point for trying to grasp the nature of the EU’s territory. These provisions define the geographic space of the EU by listing the individual Member States’ territories as well as certain exceptions.Footnote 14 Geographically, the sum is not more than its parts. The EU’s territory is in principle coextensive with the combined territories of its Member States. Now, these lists per se hardly advance our understanding of the nature of the EU’s territoriality. Recall that national constitutions occasionally refer to the territory of constituent sub-national component-entities,Footnote 15 which, however, does not render their territory dependent on these lower levels. The Treaty definition nonetheless illustrates a sobering point of departure: The EU does not control its territory in a meaningful sense. Rather, the Member States control their respective territories and define their borders under international law. The EU’s territory accordingly changes automatically in case of territorial changes on the national level.Footnote 16 The accession of a new and the exit of a current Member State provide the most obvious examples in that regard. There are, however, more subtle manifestations of such changes. For example, when a Member State gains—German reunification—or loses control over territory—French de-colonialization of Algeria—or by agreeing to exempt certain national territories from treaty application as with Greenland in Article 204 TFEU.Footnote 17 In short, EU territory is parasitic on national territory.

Not unlike a parasite’s host, national-territorial rule as an element of State authority is profoundly affected by this connection. Recent case law shows that core elements of national-territorial rule—even if protected in the EU Treaties—fail to fall outside the scope of EU law. More generally, the daily operation of the EU contributes to a remarkable de-territorialization of national rule.

II. The Effect of EU Law on National Control Over Borders and Territories

It is a truism of international law that states control their territories and borders. This central element of governing seems to be part of the state’s job description—and the above explanation of the EU Treaties appears to support this. In the EU, this is nonetheless not the end of the story. Indeed, EU Member States continue to be responsible for their borders. In a complex border dispute between Croatia and Slovenia, the Court held that such matters remain in the hands of the Member States:

In the absence, in the Treaties, of a more precise definition of the territories falling within the sovereignty of the Member States, it is for each Member State to determine the extent and limits of its own territory, in accordance with the rules of public international law . . . . Moreover, Article 77(4) TFEU points out that the Member States have competence concerning the geographical demarcation of their borders, in accordance with international law.Footnote 18

The Treaty explicitly confirms that the geographical determination of national borders remains the competence of Member States. Article 77 (4) TFEU, quite paradoxically, upholds this national competence in a supranational treaty.Footnote 19 Given that both Member States are subject to the duty of sincere cooperation towards each other, the EU, and other Member States, however, it is incumbent upon them to resolve the dispute swiftly and in accordance with international law.Footnote 20 This provides a first impression of how the EU binds Member States to one another in a way that enables the EU to exert normative influence beyond the scope of its explicit competences, with distinct consequences for national territorial rule.

Beyond this rather narrow issue of locating and controlling borders, the Member States uphold public order and claim the monopoly of force as well as unlimited authority coextensive to their territories.Footnote 21 Doing so characterizes them as sovereign states.Footnote 22 Article 72 TFEU, and its jurisdictional equivalent, Article 276 TFEU, indeed underline the Member States’ territorial claims by recognizing their “responsibility . . . with regard to the maintenance of law and order and the safeguarding of internal security.” Similarly, Article 4 (2) TEU obligates the EU to respect the territorial integrity of its Member States. Thus, national territory does not disappear through the European transformation. To the contrary, it is explicitly protected in the treaties. Think of the recent extraordinary measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the closure of intra-EU borders, as powerful reminders that national borders and national territories still exist and matter.

However, it does not follow that the way Member States govern their territory is an EU law-free zone. That is at least what the ECJ held when Eastern European Member States tried to justify their refusal to participate in an EU-wide refugee relocation scheme with recourse to Article 72 TFEU’s public-order trias and Article 4 (2) TEU. The Court confirms that not even salient areas like the maintenance of law and order constitute a domaine réservé, which would jeopardize the binding nature and uniform application of EU law.Footnote 23 In that case, the Member States in question failed to substantiate that the relocation of several refugees causes any palpable threat to their domestic public order and, consequently, could not invoke Article 72 TFEU as a defense.

This shows that the general divide between the EU’s competencies, as enumerated in Article 2-6 TFEU, and its jurisdiction or the scope of European law that arises especially from the functional nature of fundamental freedoms and various legal bases in the Treaties, applies to territoriality as well. The scope of EU law considerably transcends the EU’s explicit competences. Moreover, the Treaties explicitly mention the protection of such salient areas of state sovereignty has the counterintuitive effect of bringing the interpretation of these notions into the purview of EU law and of the ECJ. The combination of these two elements makes it the case that EU law claims a say in relation to significant territorial elements of its Member States’ governance.

So far, the EU’s territory’s derivative and parasitic nature means that its geographic reach depends on and necessarily coincides with the Member States’ combined territory.Footnote 24 That, however, does not prevent EU law from affecting and shaping the territorial sovereignty of its Member States. Aside from the recent examples discussed above, namely borders and public order, the EU claims the authority to transform national-territorial rule through its daily operation. One of the most obvious effects of EU law is a regulatory de-territorialization from the perspective of nation States. Let us take a closer look.

III. The De-Territorialization of National Rule

The EU’s legal and institutional architecture itself creates territorial cohesion in Europe. EU law’s emphasis on coherence and uniformity naturally contributes to a common European space for business, people, and states.Footnote 25 Primarily, the internal market paradigm is built upon the underlying intention to tear down any protectionist walls that unreasonably prohibit the interaction of goods and persons. Above all, the operation of the fundamental freedoms in their proactive interpretation by the ECJ has always spearheaded this development. Because the internal market is defined as an “area without internal frontiers” (Article 26 (2) TFEU), the Treaty foresees the tectonic changes it brings about for territorial rule.Footnote 26

These territory-building economic elements bring to mind how a centrally organized capitalist economy contributed to the formation of the sovereign state in the late Middle Ages.Footnote 27 And rightly so, for territoriality provides “the conceptual foundation of regulatory authority over transactions or conduct. Historically, in its strictest sense, the concept referred to the exclusive authority of a State to regulate events occurring within its borders.”Footnote 28 The EU’s way of governing creates a new, distinctly supranational kind of territoriality, that facilitates transactions across borders. In the spirit of the quote, the EU’s regulatory authority over transactions reflexively creates a new form of territoriality. This by itself fosters internal coherence and—as a necessary consequence—external delimitation. It exposes businesses and citizens alike to alternative regulatory and cultural ways, creating pressure for change and assimilation.Footnote 29 This feature significantly affects the national control of territory that the quote rightly cites as territoriality’s historical origin. It leads to “territorial competition”Footnote 30 among the Member States, which may not reserve their resources for their own people and use borders as a hurdle for imported goods unless there are good reasons.

A few examples help to get a sense of how EU law affects national-territorial rule. Consider recent developments in EU private international law, where the relevant link to determine the applicable law shifts evermore from rigid national categories, such as citizenship, towards the more flexible “habitual residence” in a Member State. This loosens the jurisdictional ties to one’s homeland in important areas such as inheritance.Footnote 31

Moreover, the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (AFSJ) demonstrates the implications of this in less economic terms. First, Member States may not refuse entry to EU citizens from other Member States anymore. Second, many of the Member States have no external borders in the traditional sense, unless they find themselves at the external border of the EU, Schengen complications notwithstanding.Footnote 32 That aspect of EU rule has shifted the focus from hard national borders to the external borders of the EU.

The European Arrest Warrant scheme (EAW), which in principle requires Member States to extradite defendants in criminal proceedings at the request of another Member State, provides a striking example within the AFSJ. Absent specific EU rules, the fundamental normative architecture of the EU—mutual trust among the Member States, sincere cooperation between the EU and Member States, as well as EU citizenship—means that extradition of a national of another Member State to their home Member State takes precedence over third-country extradition requests.Footnote 33 It thus contains a protective element connected to the EU territory. Priority is given to the home State’s decision to prosecute their own nationals before host States can extradite an EU citizen to third countries. The EAW regime at the same time involves diluting the right to stay in one’s home country because it lowers the conditions for extradition to another Member State, where one is accused of a crime. In that sense, the EAW is compensation for the free movement rules, stripping the individual citizen of the expectation to be protected in one’s home country.Footnote 34 Such extradition intrudes into the very bedrock of the State’s protective function. It affects a central link between States and their citizens. Quasi-automatic extradition of one’s own national to another State is only possible based on mutual trust in the requesting State’s capacity and willingness to secure procedural and substantive fundamental rights, which the EU’s institutional machinery facilitates and monitors.

Relatedly, the interaction between EU law and subnational authorities, namely bounded regulatory entities below the State level, reveals a further drop in the importance of national territories and frontiers. Seminal cases from Azores—the Portuguese Azores territories—via Omega—the German city of Bonn—to Walloon Waste—the Belgian region of Wallonia—have led Michèle Finck to conclude that the formally exclusive relationship between the EU and its Member States neither captures the functional permeability of State borders nor the direct relationship between the EU and these subnational authorities adequately.Footnote 35 In other words, by taking the regulatory autonomy of cities and regions seriously as a matter of EU law, the EU roots its authority claims in more local governance structures. That gives these subnational entities an independent voice in European integration, to the effect that State territoriality is more and more sidelined.Footnote 36 In addition to the emergence of a supranational notion of territory from above, EU law’s emancipation of subnational territories from below thus reduces the importance of national territory.

Finally, Article 3 (3) TEU contains a curious reference to the Union territory by listing the promotion of “territorial cohesion . . . among the Member States” as one of the EU’s objectives. It aims to offset inequalities among various regions and thereby actively and explicitly contributes to a coherent development of the polity.Footnote 37 These are not peanuts. The new Multiannual Financial Framework for 2020–2027 allocates more than €426 billion to cohesion, resilience, and values, which does not even include another €776.5 billion from the Next Generation EU instrument to tackle the challenges COVID-19 presents to the EU.

The governance technique that pervades these examples resembles the duality between deregulation and reregulation in the internal market, namely the combination of banning unjustified restrictions of fundamental freedoms and the introduction of common rules on the European level.Footnote 38 Piercing the control function of national borders while developing supranational borders shows the same regulatory and structural pattern. The EU thus provides one important illustration of the more general observation that de- and re-territorialization go hand in hand.Footnote 39 Yet, this does not mean that the minus on the Member State level exactly mirrors the resulting plus on the supranational level. Otherwise, by replicating State structures, the EU would be unable to transcend and solve the problems of its Member States.Footnote 40

In sum, the EU designs a common area for the peoples of Europe precisely by legally facilitating the mobility between individual State jurisdictions and thereby devalues the importance of national territoriality, especially of national borders. The effect is that EU membership modifies Member State territoriality permanently because it brings about these changes. Instead of, for example, primacy of EU law, which merely requires to disapply national law within the scope of EU law, EU membership transforms the very idea of national borders and national-territorial rule.

IV. Interim Conclusion: EU Law and Member State Territoriality

The Treaties express an underlying assumption about the existence of EU territory and the rest, an inside and an outside. Moreover, the EU’s territory is parasitic and dependent on the continued existence of national territory. The emerging territorialization of EU rule, which I will further explore below, does not supersede national-territorial rule.

The EU nonetheless transforms the traditional understanding of state territoriality.Footnote 41 EU law connects national territories, and during that, forms a European territory. The parasitic nature of EU territory creates the conditions for this reflexive relationship in the first place. As we have seen, EU law’s aim to create border-transcending regulatory alignment interferes with national-territorial rule and the normative salience of national borders. Various examples from private international via the EAW to the EU’s relationship to subnational authorities illustrated the diminishing importance of national territory. These are examples of what John Ruggie calls “unbundling” national territory.Footnote 42

In theoretical terms, EU membership forces the Member States to open their bounded territories to the various peoples that have committed themselves to the European project. Following Miller’s territorial rights, Member States must share jurisdiction with the EU, lose most of the control over their borders, and provide outsiders access to their resources. The EU’s effect on State territoriality is hence enormous. The EU does not weaken territorial rule in Europe, but instead renders it richer and more complex.Footnote 43 Think of the traditional function of territory to allocate responsibility to identify the local, regional, or national community responsible in case of an emergency or disaster, an issue closely connected to political authority.Footnote 44 Territoriality aims to create order.Footnote 45 Overlapping territorial jurisdictions necessarily obscure responsibilities. At the same time, they increase the available resources to tackle crises. Only very recently, the EU used the possibility to grant solidarity-aid for unforeseen occurrences under Art 122 TFEU to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19-pandemic with the SURE-Regulation.

This interference into national-territorial rule evidently raises questions of legitimacy. To what extent can the EU rightfully change and suppress the exercise of national territorial rule? Not rarely the very identity of the center relies on identity roots in its smaller communities.Footnote 46 The rationale behind the protection of national identity and territorial integrity in Article 4 (2) TEU is to remind EU actors of the independent value of the various European identities, which should be preserved despite the integration process. This constantly renegotiated bargain between the center and the lower level, as well as the ongoing tension between supranational space and local roots, remains one of the key projects for the ongoing development of the EU polity. The balancing of the two remains a constant legitimacy challenge.

It is accordingly not an exaggeration to claim that EU integration has profound effects on national-territorial rule. Because this process redefines the concept of territorial rule in Europe on both levels, however, one cannot leave out the elements of territorial rule on the EU level itself.

D. Supranational Territorial Rule: Of Jurisdiction and Borders

It is important to begin the analysis with the concept of territorial jurisdiction at the EU level. The notion of EU territory plays a remarkable role as trigger for the EU’s jurisdiction, and helps to construct a territorial-extraterritorial distinction of EU law’s reach. Moreover, the various manifestations of an inside-outside divide on the EU’s outer borders give us a clearer picture of the re-territorialization at the supranational level and the ensuing legitimacy challenges.

I. EU Territory as a Normative Concept: Supranational Territorial Jurisdiction

The introduction alluded to the notion of territorial jurisdiction as the primary manifestation of territorial rule. Moore has recently described the widespread view according to which the notion of territory itself is intrinsically connected to the right to have and exercise jurisdiction over a distinct patch of the planet that is justified by a particular moral value. In short, “territory is the geographical domain of jurisdictional authority”.Footnote 47 Her analysis naturally focuses on states. There, the paradigm of territorial jurisdiction applies in its strongest form to protect states from external influence as part of customary international law. Contrast this with the purely functional jurisdiction of international organizations, where exclusively non-territorial criteria—for example international trade disputes in the WTO case—trigger a given legal regime’s jurisdiction. Thus, the inquiry is conceptually prior to the familiar questions of private international law, namely which individual body has jurisdiction, and which substantive law applies in a given case. For what is of interest here is whether and how the EU uses territorial elements to exercise authority in the first place. In other words, territorial jurisdiction is a theoretical concept that informs how a polity or organization may legally regulate the applicability of its law and what falls under its legitimate regulatory reach.

In relation to territorial jurisdiction, ECJ jurisprudence and secondary law corroborate the interplay between the EU’s geographical space and territoriality as governance tool. There is a noticeable development towards elements of territorial jurisdiction at the EU level.

Due to the principle of conferral under Article 5(1) TEU, the EU cannot use territorial triggers alone to justify its jurisdiction. The mere fact that a legal problem arises on the EU territory does not suffice to trigger the EU’s jurisdiction. However, as already noted in Section C, the divide between competence and jurisdiction in the EU expands the EU’s normative influence on sectors well beyond its written competences. Intriguingly, the ECJ developed an element of EU law’s jurisdiction based on an autonomous notion of EU territory. According to the ECJ, the EU Aviation Directive does not infringe the principle of territoriality/sovereignty of the third state:

[S]ince those aircrafts are physically in the territory of one of the Member States of the European Union and are thus subject on that basis to the unlimited jurisdiction of the European Union.Footnote 48

The effect on the Union’s geographical territory seemingly suffices to trigger the applicability of EU law. EU secondary law seems to mirror this understanding. For example, the EU legislator uses Union territory as a jurisdiction-defining element prominently in Article 3 (1) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).Footnote 49 All these statements presuppose that the EU may legitimately employ territorial triggers for its jurisdiction.

Next, the very existence of extraterritoriality in EU law entails a territorial understanding of jurisdiction because the inside-outside divide itself is responsible for the normative difference. The ECJ has applied EU law extraterritorially for decades. For instance, the freedom of workers applies to employment contracts performed outside the EU as long as they retain a sufficiently close link with the EU territory.Footnote 50 Instead of reasoning based on State territoriality and their jurisdiction alone,Footnote 51 the Court seems to operate with an independent notion of EU territory. Various recent pieces of legislation and the accompanying ECJ jurisprudence illustrate in a comparable way the development of a principled stance on the extraterritorial application of EU law, which affects salient areas like competition, financial regulation, and internet regulation.Footnote 52

There is another intriguing facet to the extraterritoriality of EU law. Extraterritoriality is usually problematic for its intrusion into the regulatory territory of third States. The EU’s legislative compromise on the “right to de-referencing” from platforms, for example, does not extend to the platform’s worldwide operations because the ECJ recognizes the sensitivity of the otherwise far-reaching extraterritorial effects.Footnote 53 Elsewhere, the noticeable extraterritorial reach of EU law is due to “extra-territorial” triggers for the EU’s jurisdiction, like effects, anti-evasion, or transaction.Footnote 54 I would like to call them “a-territorial” triggers, however, because they reflect the inherently functional component in the EU’s governance and its competences. By defining the reach of EU law functionally—for example by letting mere effects of financial transactions within the EU suffice—the EU makes territorial claims on third countries.Footnote 55 It imposes legal obligations on them and their businesses.Footnote 56 More territoriality on the part of the EU in the sense of a deliberate restriction of EU law’s jurisdiction to the EU territory would paradoxically lead to less interference with third States. In general, the functional way that pervades the EU’s governance is inherently susceptible to flout the territorial-extraterritorial distinction so central in the relations among states.Footnote 57

The EU’s widespread use of territorial jurisdiction and the effects of extraterritorially applicable EU law on third States thus reveals various interesting features about the EU’s architecture. EU territory alone at times suffices to activate the EU’s jurisdiction. While EU institutions and academics take it for granted, it is theoretically important that territorial triggers form part and parcel of the EU’s jurisdiction. Moreover, the variegated “extraterritorial” application of EU law is not only based on a confident, purely EU law-based application of territory-related triggers, which has hitherto been confined to States. The various functional triggers also impinge on the territorial jurisdiction of third States. This is not to suggest that the EU’s jurisdiction-territory nexus mirrors its statist sibling, however. In all these examples, national territory plays a decisive role in triggering and defining the EU’s jurisdiction. And yet, these instances exemplify that EU territory matters and—even more simply—that it exists as an independent concept and normative reference point. This jurisdictional element is complemented by a noticeable inside-outside divide in relation to non-Member States.

II. The EU’s Borders and the Creation of an Inside-Outside Divide

To learn more about the boundaries of the EU’s political community, it is important to start once more with a look at the treaties. The treaties mandate a self-standing territorial inside-outside divide, which I touched upon when reflecting on the relationship between de-territorialization and re-territorialization. In particular, Article 77 TFEU—in the context of the AFSJ—requires the absence of controls of persons crossing internal borders and the efficient monitoring of external borders. The AFSJ not only creates a normatively relevant dichotomy between the inside and the outside. It also establishes quasi-hard borders on the supranational level.Footnote 58 For the evolution of an internal area of freedom resulted in Member States’ calls for an area of security and justice towards the outside.Footnote 59 In A. John Simmons’ analogy to States as property owners, they designed the EU to look more like a “gated neighborhood.”Footnote 60 Conversely, the Common Security and Defense Policy has sharpened a territorial element in EU rule with regard to the outside. It allows the EU to use civilian and military means to combat terrorism and other threats “supporting third countries” or for “missions outside the Union”.Footnote 61

These elements distinguish the EU from former empires such as the British Empire or the Austro-Hungarian Reich as prior emancipatory polities beyond the traditional State model.Footnote 62 In contrast to empires, the EU relies on concrete external borders rather than a power center with decreasing influence towards the periphery.Footnote 63 But how do these borders influence the EU’s authority claim? Insights from political geography help to tackle this question.

The EU’s architecture is characterized, much more than in the past, by a territorially fixed political community. In large part, the construction of the EU is an attempt to create a coherent political, social, and economic space. By nature, bordering is a multilevel process of re-territorialization, which raises important questions regarding the EU’s political and territorial nature.Footnote 64

Geographical boundaries play a role in the appreciation of the EU’s authority.Footnote 65 First, borders and territory appear to be a precondition for constructing a polity. Simultaneously, they raise questions about its legitimacy because their barriers and fences represent the discrimination between insiders and outsiders.Footnote 66 Second, territorial borders distinguish EU rule from traditionally purely functional international organizations. Scholarly criticism according to which EU law sometimes views the EU’s territory as just that—to wit, a geographical space instead of a normative notion—should nonetheless not be overstated.Footnote 67 The EU’s manifestation of spatial belonging is clearly both geographical and normative. This points to the tension between Fortress Europe and Europe as an ideal, special area of human hope. Claiming a particular space as the territory of the EU involves a point of reference to values that unite those on the inside.Footnote 68 In the background of the technical notion of free movement lurks a common space for Europeans. In that sense, geographic and normative elements of territory depend on each other: The harder the outer borders, the greater the need to unify the inside and to justify exclusion.Footnote 69 Conversely, a more rigorous enforcement of internal values and common standards itself accentuates the internal-external divide.

None of this is to argue that borders are necessarily morally wrong, but merely that they raise the moral profile of a polity.Footnote 70 Take the discussions surrounding the Irish border in the Brexit negotiations.Footnote 71 The imminent scenario of an external EU border on the Irish island provokes the EU—and not the Republic of Ireland alone—to justify its desire for a hard border protecting the EU’s inside and to spell out the precise object of its protection. Simultaneously, the EU needs to reconcile that desire with the task to ensure peace and stability on the Irish island. For that reason, a discussion of the EU’s territorial authority needs to consider its relationship to States outside the EU. In an important sense, the outer European borders demarcate a European space as well as marking an outer frontier of one of the Member States. This does not contradict this Article’s earlier claim that the EU does not control its borders. It merely characterizes the incessant ambivalence of two overlapping jurisdictions where identical borders fulfill distinct functions. Once again, the Brexit negotiations in relation to the Irish border powerfully bring to the fore both geographic and normative manifestations of EU territorial rule. On the one hand, there is the fear of a hard outward border with all its conflict-driving potential. On the other hand, there is the aspirational promise of an area of free movement and common values, which the EU has hitherto contributed to securing on the Irish island. The Irish border discussion shows that the European frontiers mark more than the end of a trading block. They usually mark the end of a common space for the European peoples.

III. Interim Conclusion: The Normative Significance of the EU’s Territory

This section focused on the supranational component of the EU’s territoriality. EU institutions use territorial jurisdiction, an inside-outside distinction, to determine the applicability of EU law. In many ways, on both the national and the supranational level, “territoriality remains the main control mechanism in the European Union.”Footnote 72

This legal observation is corroborated by various moral consequences of this supranational re-territorialization into a “gated neighborhood.” The internal openness through overcoming physical and regulatory borders coincides with a substantial outward exclusion. It replicates a territorially bounded architecture as a direct consequence of opening up statist territories.Footnote 73 This dichotomy creates moral problems of exclusion and raises the need to justify the divide. Brief excursions into political theory have shown that the harder the border, the more pressing the need to demonstrate the reason for protecting the inside.

To grasp the territorial element of EU rule more fully, it is important to view the role of EU citizens next.

E. How EU Citizens Shape the EU’s Territorial Rule

This Article has already shown how free movement as a central idea in the EU’s governance has a profound effect on national territorial rule. It is worth spending more time on the specific role of EU citizens in emerging elements of supranational territoriality. Indeed, one of the most remarkable examples for an evolving normative concept of territoriality in the EU stems from the Court’s coupling of membership and territory in Zambrano. Moreover, the fact that EU law gives exit rights to EU citizens triggers a whole range of territory-related legitimacy questions.

I. The Link Between EU Membership and Territoriality

The introduction of EU citizenship considerably raised the normative salience of the EU’s territory. It led to a situation in which the decision to reside in another Member State by itself triggers the application and thereby the protective rights of EU law.Footnote 74 To highlight the importance of this development, this section will briefly elaborate on the most vivid and undoubtedly exceptional manifestation of the thus created link between membership and territorial rule in the EU: The Zambrano case. According to Zambrano, a Member State is not allowed to refuse third country national parents a right of residence if that meant that their children—Member State nationals and therefore EU citizens—would, thereupon, be forced to leave the EU territory as a whole.Footnote 75 In a surprising conceptualization of EU territory, the Court links the “genuine enjoyment of the substance of the rights” of EU citizens to the entire territory of the EU and thereby conjoins membership and territorial rule.Footnote 76 In contrast to the “territory of the Member States” language of Article 20 (2) TFEU, the ECJ refers to “EU territory” in the singular.Footnote 77 Consequently, EU law does not prohibit expulsion of an EU citizen to another Member State because what matters is the EU territory in its entirety.Footnote 78 Only the threat of expulsion from the entire EU territory triggers the jurisdictional essence of EU citizenship rights and thereby the scope of EU law.

In essence, EU law interferes with residency decisions on the national level in order to uphold the minimum guarantees of the status of being a member of the EU polity. This questions an interpretation where EU territory matters exclusively in its relation to mobility and circulation.Footnote 79 In the undoubtedly exceptional circumstances outlined in Zambrano, EU citizenship serves as the sole trigger to invoke the jurisdiction and protection of EU law against the home Member State. That notwithstanding, EU citizenship does not purport to interfere with national or international law’s protection of the territorial rights of citizens against their own State of nationality. As the Court held:

[A] principle of international law precludes a Member State from refusing its own nationals the right to enter its territory and remain there for any reason . . . . [T]hat principle also precludes that Member State from expelling its own nationals from its territory or refusing their right to reside in that territory or making such right conditional.Footnote 80

The Zambrano jurisprudence implies that the ECJ structurally aligns EU citizenship with a core element of national citizenship, namely representing membership in a polity via residence within a given territory. This jurisprudence evidently does not bode well with the Member States’ sovereignty claims because the Court in effect curbs the jurisdiction of Member States over their own nationals to the extent that the exercise of such jurisdiction would de facto render EU citizenship moot. It constitutes an interesting twist that the subsidiary protection of Zambrano supports the home State-national citizen relationship, given that de facto expulsion of one’s own national/EU citizen is prohibited.Footnote 81 Beyond that, the notion of EU citizenship contributes to the explored territorialization of EU rule in other, practically far more relevant, ways, especially in relation to free movement.

II. Free Movement and Exit Rights

The territorial flexibility of EU citizens that results from their free movement rights not only contributes to territorial cohesion in the EU, as shown above. It also reconfigures the normative relationship between citizens and Member States.

Note the conceptual connection between free movement and exit rights. Ever since Locke’s argument for justifying political authority by recourse to tacit consent, exit rights entered the debate of legitimate political authority. Locke derived tacit consent to the state’s legitimate authority from a citizen’s refusal to leave the territory of their State.Footnote 82 By continuing to live in a state, citizens imply that they silently approve of the state’s rule, which renders it legitimate. Unsurprisingly, various theorists have explained how exit rights do not license mistreatment, such as—in the extreme case—a permission to violate fundamental rights of minorities on the basis that they can always leave the state in question.Footnote 83 However, even a lower threshold suggests that exit rights are no guarantor for the well-being and autonomy of the individuals given that personal, economic, or ascriptive factors can make the exercise of exit rights extremely burdensome.Footnote 84 So, how does EU citizenship come into the equation?

EU citizenship fundamentally redesigns the exit option for citizens of the Member States. In a sense, the EU makes the exit right a real, viable option for EU citizens. It offers the entire EU territory to the EU citizens. Not in the strong sense of dual citizenship, in which case the citizen could enjoy the same rights in both states.Footnote 85 However, EU citizenship enables the citizen to enter and reside in other Member States with remarkable ease. It favors the exit-possibility over Hirschman’s alternative to express discontent over the political regime of one’s home State: Voice.Footnote 86 The onus of change thus flips back to the home Member State. The viable exit option for citizens and businesses to the other Member States, combined with the voice EU citizenship gives them in host states, creates a competitive environment for these states to keep those citizens and economic agents happy.Footnote 87 A Member State may react to the pressure of free movement by benevolent policies for mobile workers to the detriment of immobile workforces, or by encouraging free movement in times of economic crises to counter unemployment, thereby putting the citizen in charge of improving the situation.Footnote 88 This competition facilitates a constant renegotiation of the social contract in the Member States while simultaneously strengthening—since the Member State is forced to care about its citizens—and weakening—since it is easier to leave the state—the bond between a citizen and their home State. The buzzword for this competition in the EU is free movement.

Enabling EU citizens to vote with their feet by moving to another Member State not only realizes a distinct idea of justice by helping EU citizens to pursue their idea of a “good life” elsewhere.Footnote 89 It also constitutes one of the EU’s most significant legitimacy-related innovations with profound effects on both national-territorial rule and the development of supranational territoriality.

III. Interim Conclusion

Article 20 TFEU entails a right to reside in one’s home State under the Zambrano case law’s narrow conditions that complements international law’s broader protection of the right to stay there. In short, Article 20 TFEU protects the right not to move. By contrast, Article 21 TFEU creates a right to move to, reside in, and be integrated into the host State. Article 21 TFEU protects movement. Both complement each other to grant a minimum right to stay in the entire Union territory with varying levels of EU law protection beyond that.Footnote 90 This jurisprudence thus charges the EU territory with normative value.

These two components forcefully illustrate the influence of EU citizenship on developing a supranational notion of territoriality. For one, EU law gives EU citizens a qualified right to residence on the entire EU territory, which does not entail a right to reside in every Member State, but a right not to be expelled from the EU territory in its entirety. For another, relocating to a different Member State immediately loosens the jurisdictional ties of EU citizens to their home State while creating new such ties to the host State.

This brings us to the final element of the EU’s territoriality. Considerable functional flexibility pervades the territorial architecture of the EU, which perhaps more than any of the other elements illustrates the sharp contrast between the EU and the territorial claims of even federal States.

F. Territorial Functionalism, or the Many Territories of Europe

Instances of territorial rule do not exclude non-territorial governance elements. The most prominent of the latter, certainly in the EU context, is functional rule. Apart from the functional elements in the way the EU exercises its competences, the notion of EU territory itself is inherently functional, which distinguishes it sharply from state territorial rule.

I. Functional Governance

Functional governance means “designed to serve a function,”Footnote 91 which is, to repeat, the traditional domain of international organizations. They are created and intended to serve a functional, delimited mandate. This definition makes such an entity’s inherent limits evident because the scope of action of the entity is confined to serving that purpose. Much ink has been spilled on the degree of the EU’s purported emancipation from its functional origins.Footnote 92 This Article is interested in how functional elements in the EU’s architecture interact with the above territorial elements and thus add further contours to its authority claim.Footnote 93

As is well known, many of the EU’s core competences are functional. Instead of delimiting a certain substantive regulatory activity, they formulate a regulatory goal that usually transcends various individual sectors.Footnote 94 We saw earlier how this leads to a de-territorialization of national rule. For example, Article 114 TFEU as the core legal basis in internal market matters encompasses the regulation of innumerable sectors, if they “approximate the provisions of law . . . which have as their object the establishment and functioning of the internal market.” We further uncovered that functional triggers enable EU law to have extraterritorial effect and influence the regulatory autonomy of third States. This pervasive functional element complements the above-mentioned territorial rule and makes demarcating the precise reach and limits of the EU’s authority a tricky task. As explained, EU law’s oft functional architecture enables the penetration of core elements of national territorial rule in the first place.

II. The “Variable Geometry” of EU Law

In remarkable contrast to States as unitary and territorially bounded entities, there seems to be a variety of functionally driven European territories. That makes territorial flexibility an element of the EU’s DNA.Footnote 95 Put differently, much of the EU’s territorial rule is inherently functional itself.

Consider the possibilities for differentiated integration from opt-outs to enhanced coordination on the primary-law level. Opt-outs—enacted as protocols to the treaties—allow a Member State to be exempt from certain fields of action, such as the common currency. Conversely, enhanced coordination creates the possibility for a group of Member States to deepen integration in specific fields without the non-participating Member States. The result is remarkable. Only six Member States currently partake in the entirety of EU action.Footnote 96 This “variable geometry” continues at the level of secondary law, where the room to maneuver when implementing directives and explicit derogations in secondary law contribute to the uneven application of EU law in the Union territory.Footnote 97

Underneath these options of contractual fine-tuning lies an even more fundamental territorial flexibility. The possibilities to accede to and leave the EU contrast categorically with territorial shifts at the State level.Footnote 98 While the latter is often characterized by secession and war—recall the renewed war between Armenia and Azerbaijan about Nagorno-Karabakh in the EU’s neighborhood)—EU membership is not a territorial zero-sum game in the sense that States would lose their self-standing territory. As the Treaties make clear this represents one of the most apparent instances where the EU lacks control over its territory.Footnote 99 And it has a considerable influence on framing the quest for the EU’s legitimate authority. Because the EU allows the “secession” of an entire Member State’s people. In other words, the EU itself provides more remedies to unjust treatment than States do.Footnote 100 In a sense, the EU takes the peoples’ continued consent to the EU project dead serious on a theoretical level, though Brexit has evidenced the myriad practical problems associated with the decision to leave.

A view of the EU’s external relations further supports this picture of flexibility. In fact, the territorial flexibility noticed internally applies externally as well. From the European Economic Area (EEA) to the Bilateral Agreements with Switzerland, contractual arrangements export the application of EU law to neighboring States and thereby enlarge the territorial reach of EU law. This leads to awkward qualifications of third States as “almost – but not quite – internal.”Footnote 101 This export of EU law results in flexibility towards both Member States and adjacent States. Only recently, the close alliance between the EU Member States and Iceland as a European Free Trade Area (EFTA) State led the Court to conclude that national courts have to inform EFTA States about a pending extradition request from a third state concerning one of their citizens, and give priority to a surrender request from that EFTA-State.Footnote 102 The Court remarkably extended the Petruhhin rationale that prioritizes intra-EU surrender over third-country extradition requests to cover the EEA members, which concluded extradition agreements with the EU. The important point for present purposes is that the territorial entanglement of some neighboring States with the EU allows these non-Member States to profit from one of the most salient features of the EU’s territorial rule, namely the European Arrest Warrant and its priority over third country extradition requests. The nexus between EU law and territoriality thus goes beyond the EU’s borders.

III. Interim Conclusion: Relative Territoriality

To sum up, all these elements lead to territorial flexibility or “weak territoriality”Footnote 103 that is alien to any conceivable form of territorial sovereignty. The above elements of the territorial rule have not led to a uniform regulatory space, where all European laws apply to the entire territory and only to the Union’s territory. Instead, the EU consists of a variety of spaces, areas, regions, and networks. And while that may be deplorable from the perspective of unity and uniformity, it has the normative advantage of accommodating very different visions of EU integration in the Member StatesFootnote 104 as well as idiosyncratic understandings of domains which any national demos wants to protect, such as military neutrality or one’s own currency.

The eventual territorial configuration of the EU thus remains a priori unfixed because it is bound to vary following accessions to or exits from the EU.Footnote 105 The scope of EU law moreover does not overlap with its territorial reach. This decoupling of coincidental territorial and regulatory rule constitutes a central feature of, rather than a deficiency in, the EU’s architecture.Footnote 106 It evidences the delicate balance between preventing cherry-picking and endorsing the legitimating force of such liberating flexibility.Footnote 107

This forcefully illustrates not only the theoretical contrast between the EU’s territorial rule and State territoriality, but also how these functional elements mitigate various of the above elements and thus soften the EU’s territorial claims as a whole. The full picture is thus a relative one.Footnote 108 The in-built territorial flexibility weakens the uniform and coherent application of EU law I described earlier. The rather hard border that the AFSJ creates and the complementing mechanisms explained previously are pierced by the web of legal relations to third States. The EU’s territorial claims thus intertwine territorial cohesion with functional options. Conversely, the EU’s authority has both functional and territorial limits.Footnote 109

Before focusing on the legitimacy challenges the EU’s territorial claims trigger, let me reiterate the main findings of our journey through the land of Europe.

G. Summary: The EU’s Territorial Claims

Where does this leave us regarding an account of the EU’s territorial claims? The analysis so far shows that we need to meet sweeping statements according to which the end of the law-territory nexus in Europe is nigh with a certain caution.Footnote 110 The EU defies cosmopolitan hopes for the decline of bounded authority in Europe and the belief that spatial frontiers are a relic of the past. Instead, the EU develops its own model of territorial rule. Similarly, labeling the EU a “deterritorialized demoicracy”Footnote 111 misses the point by neglecting the re-territorializing aspects and the EU’s respect for and effects on national territory. This distinguishes the EU from traditional international organizations when it comes to territoriality. For the UN and the WTO do not claim any territorial authority. They do not represent or administer a bordered political space in any normatively relevant way.

Vice versa, describing the EU’s territorial claims as “(quasi-) national authority” is equally unwarranted because it neglects the qualitative differences to statist territoriality.Footnote 112 The above elements of re-territorialization do not mimic State territoriality and the EU’s strategy of territorial control departs considerably from its manifestation in nation States.Footnote 113 Despite the far-reaching impact of these territorial elements of the rule, the EU does not claim full control over the Union’s territory. Rather, it claims its limited share of control. Perhaps we can adapt Sack’s metaphor, in which he compares the difference between personal and territorial rule to parents trying to prevent their children from playing with unsuitable items. Parents could either explain or ban each item individually. Alternatively, they might as well lock them up in a room.Footnote 114 In terms of this Article, the EU represents a building with twenty-seven accessible rooms. It retains an outer boundary while opening the individual rooms to be used jointly. Naturally, such an arrangement makes it more complicated to decide which objects are for common use and which are not. In other words, it makes it more complicated to delimit jurisdiction and competences.

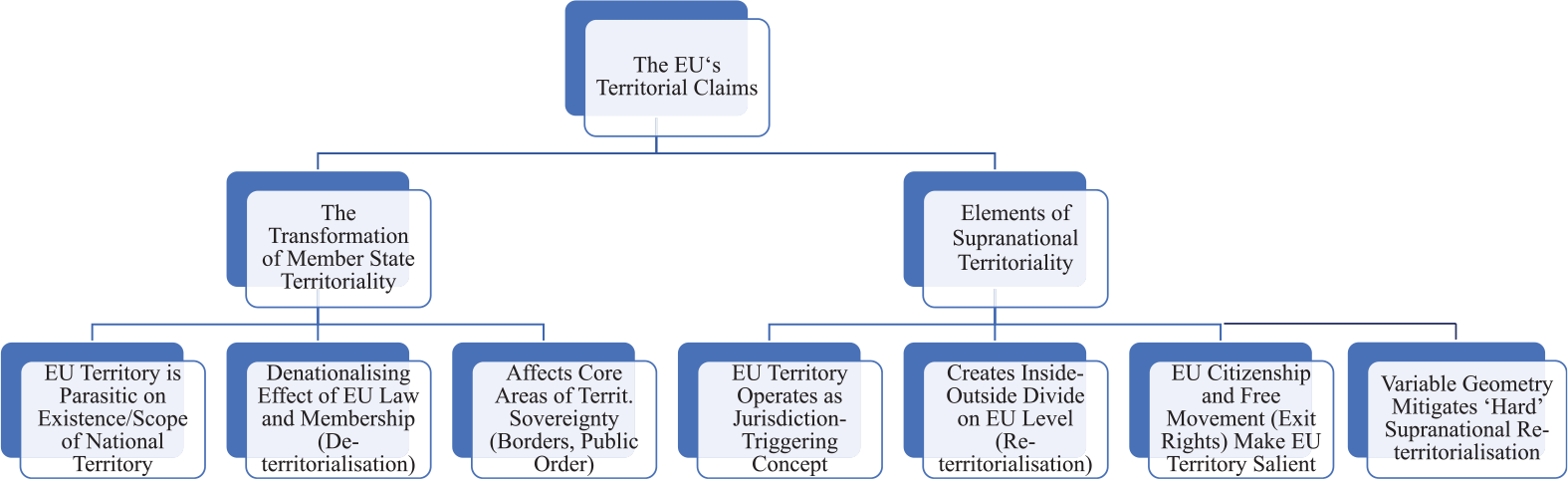

Ruggie thus correctly claimed that territorial rule neither historically nor conceptually necessarily entails exclusivity or mutual exclusion.Footnote 115 The EU creates a framework with complementary and sometimes conflicting notions of territory in distinct yet interrelated polities. The EU, in essence, claims the authority to pierce strong statist notions of territorial rule in the service of a looser, though equally bounded reconceptualization on the EU level, ultimately in an attempt of supranational polity formation. The table below will help visualize the individual elements.

Alas, this overview shows that it remains difficult to pin down the EU’s conception of territorial rule. I deliberately refrain from labelling it. The evidence of the individual elements of the EU’s conception of territoriality above suffices to understand what the EU’s territorial claims involve. In relation to the State, Ralf Michaels has shown very recently how territorialization not only creates both sovereignty and territory as well as their interrelationship in a “strange loop.” Footnote 116 It also influences the legitimacy of this bond. An equivalent process is occurring in the EU. By that I mean that the EU’s territorial claims induce a territorialization that affects the EU’s authority claim and on a specifically European notion of territory that is thereby created. This normative chain leads to the issue of legitimacy, for example, issues as to whether these territorial claims are valid. More succinctly, do we have a theory that explains the moral grounds of the EU’s territorial rule?

H. In Search of the Legitimacy Basis for the EU’s Territorial Claims

The main task of this Article so far was to uncover and analyze the EU’s territorial claims. While most territoriality theorists on the State level agree on the substance of the territorial rights a typical State claims, I have shown that the same cannot be said about the EU. The EU’s territorial claims are comparatively undertheorized. While studying these claims, we came across various legitimacy challenges, such as their profound effect on national territorial rule, the need for justifying an increasing inside-outside divide across normatively salient EU borders, or the recalibration of the EU citizens’ relationships to home and host States. The bigger question this survey raises, though it cannot fully answer in the present Article, is: Does the EU have a right to these territorial claims?

In this context, Charles S. Maier asked pointedly: “Yet without ethnicity, what is left to animate a sense of territory?”Footnote 117 For some, a “community of values” based on Article 2 TEU explains what holds the bounded place of the EU together.Footnote 118 This is not to suggest that the same has been true since the creation of the European Communities. The values in Article 2 TEU nevertheless become ever more prominent in the configuration of the EU’s authority claim, especially in their evocation by the EU institutions.Footnote 119 In a similar vein, Lindahl argues that a bounded territory necessarily contains a claim to commonality in the sense that the EU’s territory becomes “the EU’s own place” through the selection of values that unite those on the inside.Footnote 120

Because the very same values form part of the constitutional orders of the Member States whence they derive, it seems that values like democracy, rule of law, equality,Footnote 121 and fundamental rights per se cannot serve as the sole basis for the EU’s territorial claims. For that would allow the Member States to prioritize their national, idiosyncratic understandings of these values, which have historically found their genuine expression in such national political communities. In other words, despite their moral importance, these values seem too feeble to animate and legitimize the remarkable territorial claims described earlier.

A more promising route in the search to legitimize the EU’s territorial claims lies in the capacity of the EU to provide a political community beyond the State best understood as a demoicracy, as a forum for the European peoples to govern “together but not as one”.Footnote 122 In developing this idea, it is necessary to translate recent scholarship on the moral grounds of a State’s territorial rights to the supranational level. There, David Miller argues that the collective demos gives meaning to a place and underwrites territoriality. In his view, the national people ultimately bear territorial rights.Footnote 123 Margaret Moore similarly argues that territoriality provides a political community with a mechanism to exercise normative control over a bordered space, which enables it to express a specific idea(l) of how it intends to live there.Footnote 124 She explicitly connects territoriality to popular sovereignty. Anna Stilz agrees with these theorists on the relevance of popular self-determination for the territorial sovereignty of States. In her account of political autonomy, a legitimate territorial State allows a people to realize the shared commitment to living in a joint community respecting individual and collective self-determination.Footnote 125 Despite important differences among these accounts, they all find the legitimacy basis of a State’s territorial rights in various forms of popular self-determination, for example, the moral relationship among the citizen that share the respective territory.

Translated to the EU level, this implies that we need to search for a morally significant relationship between the EU and its subjects that allows the EU to claim territory in the first place. Because there is no single EU demos, it will not be in the same way as States relate to their people as a single collective. However, in light of the qualitatively weaker claims the EU makes, it does not have to be. Instead, the EU is supported and run by a collective of collectives, namely the European demoi, which remain organized and constituted separately in and as statist political communities. As we have seen earlier, part of the nature of EU territoriality is its infection by the choices and values of the peoples who have mutually opened their borders to each other. Thus, the justification for the internal-external divide in Europe could perhaps derive from the idea that the EU marks a place for the peoples of Europe and allows them to relate to each other as equals. EU borders would consequently base their moral significance on the way in which they facilitate how the EU peoples jointly exercise their self-government. The EU’s territorial claims would be an expression of a moral community defined by the interdependence of self-governing peoples.Footnote 126

Recent literature has started to explore this path. For example, Richard Bellamy scrutinizes the legitimacy of the EU’s variable geometry discussed above from a particular demoicratic perspective he calls “republican intergovernmentalism.”Footnote 127 In his view, the various instances of differentiated integration can be demoicratically justified because and to the extent they realize three important values: Fairness, impartiality, and equity.Footnote 128 Bellamy thereby rightly emphasizes how the demoicratic architecture of the EU respects the popular self-determination of the individual demoi on the national level and takes their heterogeneity into account. But why focus only on differentiated integration? Demoicracy is a promising theoretical lens concerning the evaluation of the entirety of the EU’s territorial claims discussed above. This is especially true for more robust versions of demoicracy that emphasize the value of supranational institutions, especially the EU legislator and the ECJ, for administering the demoicratic interdependence of the EU peoples. Demoicracy thus understood focuses on the EU peoples as human collectives at the heart of the EU polity, which helps to translate the above State theories that emphasize popular self-determination to the EU level.

A demoicratic justification is not only attractive because it helps to conceptualize territorial claims in a supranational political community composed of sovereign Member States. Demoicracy is itself characterized by the reflexive relationship between autonomous national demos and interdependent demoi, which lies at the heart of the territorial claims analyzed in this Article. Take the brief discussion above in relation to the obligation to protect the Member States’ territorial integrity in Article 4(2) TEU to show that the EU’s territorial claims ought to be compatible with the legitimate territorial claims of its Member States. A demoicratic justification is also well-apt to evaluate the jurisprudence discussed in the introduction that sparked the present reflections. The suggestion of the Court in Slovenia/Croatia that it is the Member States’ legal duty under Article 4(3) TEU to “strive sincerely to bring about a definitive legal solution . . . and to bring their dispute to an end by using one or other means of settling it”Footnote 129 does not sound like an outrageous transgression of competences, but as inspired by the cooperation of peoples that underwrite the EU territory. The ECJ’s recent interpretation of the GDPR to require third countries to ensure “essentially equivalent” data protection can similarly be motivated by the aim to guarantee the consistent and high level of protection of personal data throughout the EU.Footnote 130 The ECJ thus protects the legal regime the Europeans have given themselves in demoicratic deliberations in the EU legislative process that resulted in the GDPR. These examples illustrate both why we need a theory to evaluate the legitimacy of the EU’s territorial claims and why demoicracy is a good starting point. The full development of such a theory, however, must wait for another day.

I. Conclusion

In the writings of important thinkers from Aeschylus over Pope Pius II to Montesquieu, Europe—both as a place and an idea—has historically been defined by what it excludes as much as by what it includes.Footnote 131 To my mind, the EU inherits and institutionalizes this historical legacy, which its various territorial claims make explicit.

The EU joins individual national territories together to form a bounded EU territory.Footnote 132 It does not imitate statist territoriality. That is, it does not claim ultimate authority over a distinct chunk of the earth.Footnote 133 Instead, the EU’s leitmotif is to open national territories and to create a transnational, mutually integrating, and yet bounded space. It de-territorializes national rule to a considerable extent and re-territorializes a different version of territorial rule on the EU level. In sum, territoriality—as a distinctly supranational normative relationship between peoples, place, and power—forms part of the EU’s authority claim. Succinctly: “The territoriality of the European Union is much different from that of the modern States, but European integration is certainly not the end of territoriality.”Footnote 134

While this Article briefly explored the idea of demoicracy in this regard, we still lack a convincing theory that provides a moral standard to legitimize and evaluate the EU’s notion of territorial rule. Especially considering the recent jurisprudence, which, as a result, must walk on this theoretically untrodden path, it is about time we develop one.

Josef Weinzierl is a DPhil (PhD) candidate at the University of Oxford (Faculty of Law).