4.1 Introduction

Historic preservation efforts typically invite controversy, especially in high-cost cities. Advocates of preservation loudly trumpet the benefits of protecting the historic assets of a city, while critics charge that preservation freezes city neighborhoods and constrains their vital growth and development. Few observers have provided a balanced and thorough assessment of these costs and benefits, yet such an assessment is critical as city leaders make choices about which properties and neighborhoods to protect and preserve.

On the one hand, historic preservation clearly delivers benefits. The creation of historic districts may help to strengthen neighborhood identity, encourage social cohesion, and increase property values by providing certainty about future development. As Strahilevitz (Chapter 5, this volume) notes, preserving history – even a “fake” history created artificially to commemorate nonevents – has the power to generate feelings of community through a shared narrative of place-making. More fundamentally, preservation protects critical architectural and historical assets for future generations and provides a tangible link to our past. In New York City, preservation efforts have protected such architectural treasures as Grand Central Terminal and such classic nineteenth-century brownstone neighborhoods as Brooklyn Heights. We can still see the Greenwich Village townhouses where Edith Wharton, Hart Crane, and Malcolm Cowley were inspired to write and the Harlem brownstones where W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Count Basie, and other artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance brought to life twentieth-century African American culture. These historic assets are enjoyed not only by local residents, but also by visitors who travel to experience these historic buildings and neighborhoods.

On the other hand, historic preservation places constraints on a city’s ability to grow and develop by limiting the opportunity to construct new buildings or increase density on protected sites. Like other land use regulations, historic preservation rules impose new constraints that often halt the demolition of older buildings and limit the size and density of any newer ones. By imposing supply restrictions, the preservation process is likely to lead to higher housing prices and rents, both citywide and, quite possibly, within individual districts. By limiting the supply of rental housing through restrictions on new construction activity, it may drive overall prices up across the city. The requirements for higher-cost building materials in historic districts may translate into higher rents, creating obstacles for low- and moderate-income households to live in these neighborhoods. In the long run, these restrictions could limit the growth and economic development of cities as businesses seek out other places with lower housing costs and wages.

Decisions about which properties and neighborhoods to preserve are often politically charged, pitting preservation advocates against real estate developers. Developers lament the onerous restrictions the preservation process imposes while preservation advocates charge that the development process undervalues characteristics of the city that cannot be easily monetized in property transactions. Without a preservation process that explicitly values the historical character of neighborhoods and buildings outside of the market, these advocates worry that many places that contribute to the rich history and cultural fabric of the city will be lost to new development.

In this chapter, we argue for a more explicit and balanced assessment of the costs and benefits of preservation efforts in New York City. We focus on the establishment of historic districts, rather than individual landmarks, because these districts cover far more properties than individual landmark designations and, as a result, tend to invite more controversy. In calling for a balanced analysis of the costs and benefits, we acknowledge that many of the benefits of preservation are hard to quantify. After all, how do we put a dollar value on the existence of Grand Central Terminal or quantify the enjoyment of the streetscape of Greenwich Village by residents and visitors? But the difficulty in quantifying the full set of benefits does not mean we should avoid quantifying the costs.

To offer a balanced perspective on historic preservation, we offer new evidence on the development constraints imposed by historic preservation. We do so by calculating the amount of unbuilt floor area within historic districts and comparing the density and development of lots inside historic districts and lots in the neighborhoods immediately outside of them. In brief, we find that historic districts are built to a similar density level as the neighborhoods surrounding them, a finding that appears to suggest minimal constraints. However, we report that less new construction takes place in historic districts and that residential soft sites, defined as lots that are built to less than half of their zoned capacity, are less likely to experience redevelopment when they are located in historic districts. To create a more balanced approach to historic preservation, we argue that the planning process in New York City should consider these costs of preservation alongside the important, but less tangible benefits that preservation creates for the city. We conclude with a set of procedural suggestions for how the city can better make decisions about historic preservation in ways that balance their benefits against other planning goals.

4.2 The Landscape of Preservation in New York City

Established in 1965, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designates historic neighborhoods, properties, and scenic landmarks for protection under the Charter and the Administrative Code of the City of New York (Allison Reference Allison1996; Wood Reference Wood2007). In this capacity, the LPC is empowered to preserve historic districts that contain buildings with a unique historic or aesthetic appeal, represent one or more architectural styles in the city, and create a distinct body of urban history. While designated historic districts may include properties that do not contribute to the unique character of the neighborhood, a large majority of properties included in a historic district are supposed to contribute to the architectural, cultural, or historic character of a designated neighborhood.

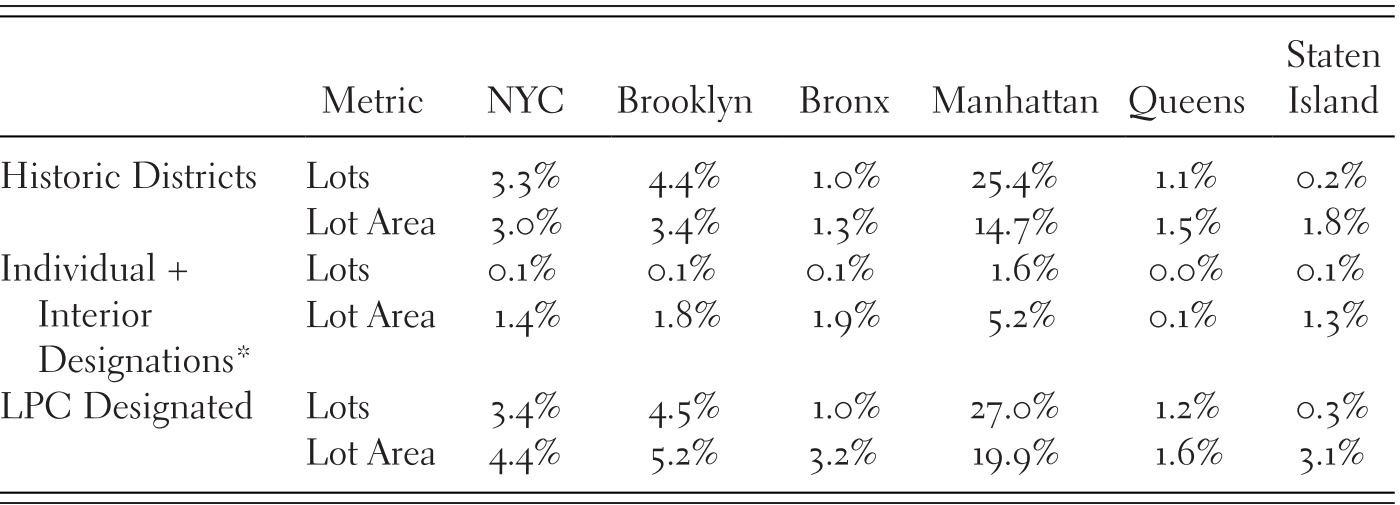

Since the establishment of Brooklyn Heights as the city’s first historic district in 1965, the LPC has designated more than 100 districts across the five boroughs of New York City. By the end of 2014, with the designation of the Chester Court Historic District, the LPC had created 114 unique historic districts.1 Although these designations have occurred in communities throughout the city, they are largely concentrated in only a handful of areas. In Manhattan, historic districts are located disproportionately on the Upper East Side, the Upper West Side, and portions of the borough south of 14th Street, as shown in Figure 4.1. In Brooklyn, historic districts are concentrated largely in downtown Brooklyn and the neighborhoods surrounding Prospect Park.

Figure 4.1 New York City Historic Districts and Extensions Added, by Decade

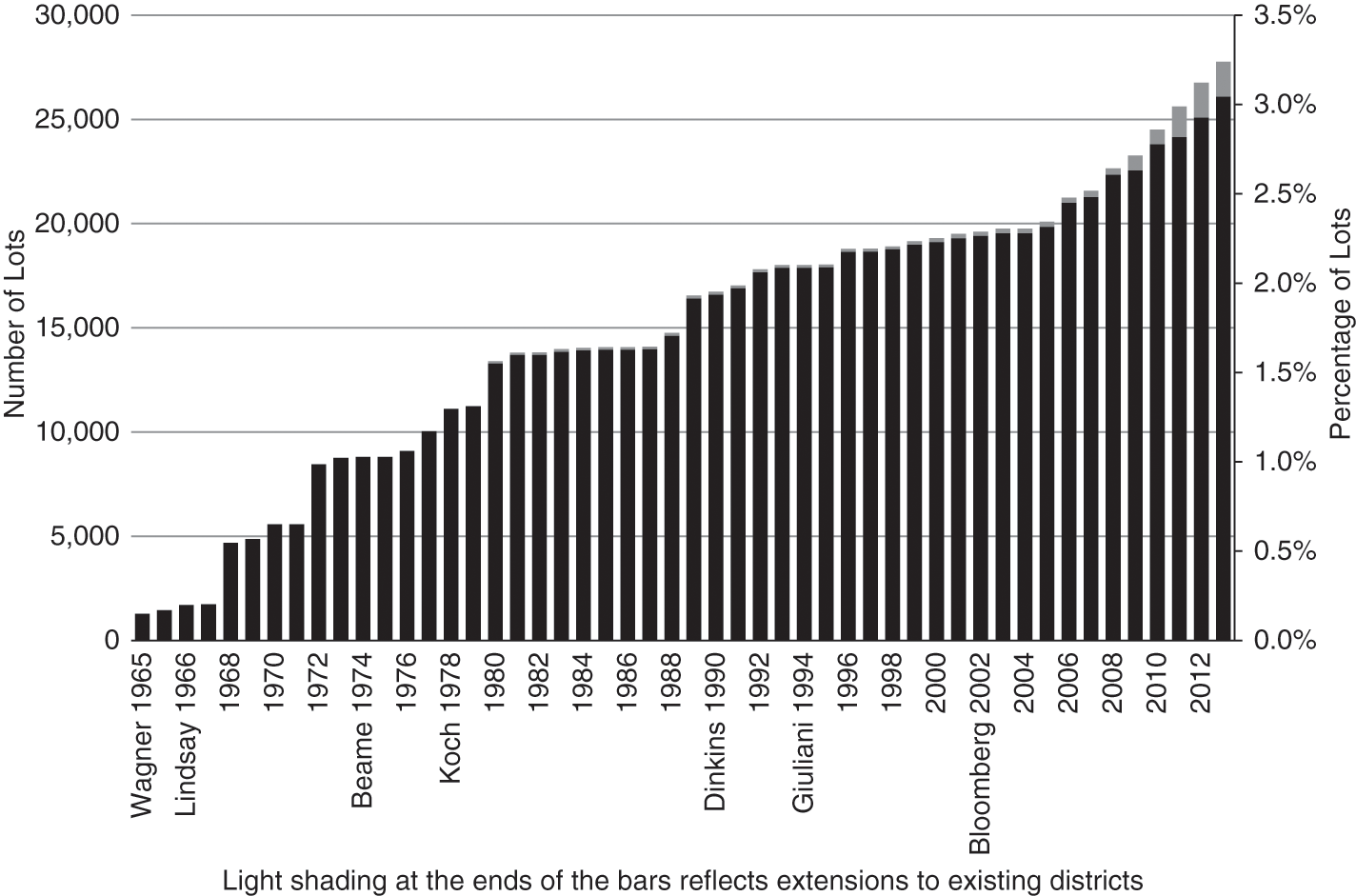

As the number of historic districts has grown over the past five decades, so too has the amount of land regulated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Figure 4.2 shows the growth in the number of lots included in historic districts over time, highlighting this growth across different mayoral administrations. The figure reveals a relatively steady pace of designation since the 1960s. By the end of 2014, there were more than 27,700 lots in historic districts in New York City. On average, district designations added 557 lots each year, though the pace of growth has varied across mayoral administrations. Mayor Wagner’s single year saw the designation of 1,279 lots, while Mayor Beame’s administration added an average of only 172 lots annually over his four years in office. While Figure 4.2 suggests a steady increase in the number of lots protected through the preservation process, it is worth noting that only 3.3 percent of lots were located in a historic district at the end of 2014. If preservation were to continue at the same pace going forward, it would take more than 700 years before the majority of the city’s lots were in designated historic districts. In Manhattan, however, it would take only another 50 years.

Figure 4.2 Count and Percent of City Lots in Historic District, by Year

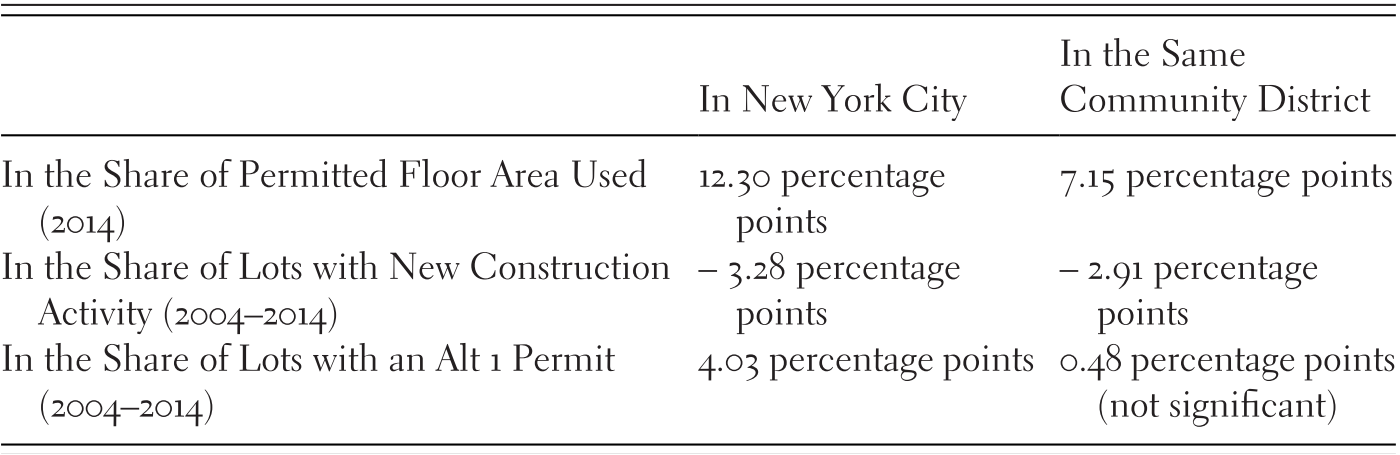

Because lots in New York City are not uniformly sized, it is also useful to examine the proportion of total lot area included in historic districts. We report the comparisons between lots and lot area in Table 4.1. By 2014, about 3.3 percent of the lots in the city were regulated as part of a historic district. Historic districts covered about 3 percent of lot area, or slightly more than 125 million square feet of land, across New York City. These aggregate measures for New York City mask substantial variation across the five boroughs. In Manhattan, more than 25 percent of lots and nearly 15 percent of lot area were located in historic districts by 2014. These totals amounted to more than 50 million square feet of land on 10,762 lots. For critics of historic preservation worried about the impact of preservation policies on construction and development, the square footage of land regulated by the LPC in Manhattan is a worrying indication of excessive regulation in the city’s densest borough.

Table 4.1: Percent of Borough and New York City Lots and Lot Area Regulated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2014

| Metric | NYC | Brooklyn | Bronx | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historic Districts | Lots | 3.3% | 4.4% | 1.0% | 25.4% | 1.1% | 0.2% |

| Lot Area | 3.0% | 3.4% | 1.3% | 14.7% | 1.5% | 1.8% | |

| Individual + Interior Designations* | Lots | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Lot Area | 1.4% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 5.2% | 0.1% | 1.3% | |

| LPC Designated | Lots | 3.4% | 4.5% | 1.0% | 27.0% | 1.2% | 0.3% |

| Lot Area | 4.4% | 5.2% | 3.2% | 19.9% | 1.6% | 3.1% |

Note: *The individual + interior designation row includes only designations not within historic districts.

While the table shows that 1.4 percent of lot area for New York City is covered by a lot containing an individual or interior landmark, the percentage drops to 0.6 if we restrict to the building footprint of individually designated landmark structures.

However, in the other boroughs, the LPC regulates a substantially smaller share of lots.2 Table 4.1 highlights this variation across boroughs. In Brooklyn, for example, only 4.4 percent of lots – and 3.4 percent of lot area – were regulated through historic districts by 2014. This includes approximately 37 million square feet of land located on 12,276 individual lots in the borough. In Queens, only 1.1 percent of lots and 1.5 percent of lot area were included in historic districts at the end of 2014.

4.3 Theory and Past Literature: Benefits and Costs of Historic Districts

The preservation of historic neighborhoods is likely to generate costs and benefits both for the residents of designated neighborhoods and for the city as a whole. To date, much of the research studying the impact of historic districts examines the net benefits property owners enjoy within districts, focusing specifically on housing price impacts following historic designation. Studies relying on longitudinal data to examine price changes in the wake of designation generally find that historic preservation has a negligible or even negative effect on property values (Asabere, Huffman, and Mehdian Reference Asabere, Huffman and Mehdian1994; Coulson and Leichenko Reference Coulson and Leichenko2001; Heintzelman and Altieri Reference Heintzelman and Altieri2013; Noonan and Krupka Reference Noonan and Krupka2011).3

Been and colleagues (Reference Been, Ellen, Gedal, Glaeser and McCabe2016) offer a model showing that the net effect of historic designation on the value of properties within the district is theoretically ambiguous. On the one hand, designation restricts the changes property owners can make to their buildings and largely prohibits demolition and redevelopment. As such, designation should reduce land and property values. On the other hand, designation minimizes the risk that new investments in neighborhoods will undermine the distinctive character of a historic community. As such, designation should boost property values to the extent that it preserves the historic character and architectural fabric of a neighborhood.

This model suggests that these relative costs and benefits will vary across neighborhoods. In neighborhoods where buildings are initially built to the allowable zoning cap or demand for the location is low, preservation should increase property values because owners are not giving up much in terms of development rights. However, in neighborhoods where demand is high and heights are far below the allowable zoning cap, the lost option value will be large. In those neighborhoods, we would expect property values to increase less, or even to fall, following the designation of a historic neighborhood. In addition, preservation should provide more benefit to owners if the neighboring historic homes preserved by the district rules are more aesthetically attractive.

Studying New York City, Been and colleagues (Reference Been, Ellen, Gedal, Glaeser and McCabe2016) undertake empirical work that largely confirms the predictions of their theoretical model. Designation appears to raise property values within historic districts, but only in the lower-valued boroughs outside Manhattan. Further, designation has a more positive impact on prices in neighborhoods that score higher on a measure of aesthetic appeal. Notably, properties located in the immediate neighborhood surrounding the historic district, defined by a 250-foot buffer, also experience a boost in property values following designation. These nearby homes enjoy many of the benefits of preservation, including neighborhood continuity and minimal risk of new development, without the restrictions imposed on individual property owners. Although the boundaries of existing districts are modified only occasionally to include additional lots, property owners in buffer zones may anticipate opportunities for future inclusion in an expanded historic district.

In addition to the changes to property values, historic preservation is likely to bring other long-term changes to designated neighborhoods. McCabe and Ellen (Reference McCabe and Ellen2016) report that the socioeconomic status of a neighborhood rises and the poverty rate declines after designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. While this process of community “upgrading” likely benefits many neighborhood residents, it may also create obstacles for low- and moderate-income renters looking for affordable housing in designated historic neighborhoods. As Phillips (Chapter 6, this volume) reminds us, physical preservation of architectural treasures, like churches, may do little to preserve the social capital in a community. In their conversion to residential units, these buildings often lose the role they played as key community institutions.

Beyond the impacts within individual neighborhoods, historic preservation efforts create benefits and costs for much broader populations, many of whom do not live in the neighborhoods protected by the preservation process. City residents and tourists alike often visit, enjoy, and learn from the architectural examples and cultural landscapes preserved through historic designation. These districts contribute to the creation of a distinctive identity for the city, promoting tourism and contributing to economic development. A set of comparative case studies argues that historic preservation has helped to fuel the economic revitalization of downtown office and retail districts and thereby helped to further broader economic development (Ryberg-Webster and Kinahan Reference Ryberg-Webster and Kinahan2014; Wojno Reference Wojno1991), although these studies tend to focus on National Historic Trust designation, rather than local designations. Designation through the National Historic Trust often comes with accompanying financial benefits that are likely to contribute to this process of economic development.

While preservation efforts may support tourism and contribute to economic growth, such benefits may come at the cost of restricting the supply of housing citywide. Critics contend that widespread historic preservation puts pressure on cities already grappling with challenges to building a sufficient supply of affordable housing (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2010). Yet, there has been little effort to quantify the impact of preservation on the citywide supply of housing, or to identify the number of housing units that could have been built absent historic preservation efforts. To the extent that historic designation restricts the supply of housing within districts, it will also restrict the overall supply of housing in a city unless other areas outside of the district are upzoned to compensate for the lost development capacity. Although regulating a small number of lots through the historic preservation process is unlikely to dramatically reduce the overall supply, as the number of lots included in historic districts increases, concerns about supply restrictions become more valid. In cities with both a robust preservation process and a tight housing market, restrictions imposed by historic designation could put upward pressure on housing prices and rents, ultimately limiting economic growth, heightening economic segregation, and contributing to concerns about housing affordability.

4.4 Historic Preservation, Growth, and Development

Critics of historic preservation policies often express concern about the regulatory burdens imposed by efforts to protect historic neighborhoods. In protecting historically significant neighborhoods from changes to the historic character of a community, the preservation process may also limit opportunities for continued growth and development across the city. Critics contend that preservation policies restrict the buildable capacity of neighborhoods, eliminate opportunities for new construction, and inhibit the redevelopment of residential soft sites. If so, then historic preservation policies may contribute to the crisis of affordable housing by constraining opportunities to increase density or build additional housing.

There has been little empirical research to formally analyze the degree to which historic districts constrain development. Given that designation is clearly not random, estimating the impact of historic districts is challenging. For example, historic districts are more likely to be established in areas with older homes. It is possible that historic districts are proposed in neighborhoods that don’t already have other zoning constraints, or that these zoning constraints are more likely to be adopted in areas without historic buildings. Even though we do not claim to precisely identify the impact of historic districts, we seek to better understand the relationship between preservation and development by comparing the density levels, buildable capacity, and construction activity on lots inside and outside of historic districts in New York City.

We begin by comparing the built density of lots located inside these districts with lots located outside of them, including the fraction of allowable density used. Next, we consider new construction and alteration activity on individual lots. By comparing lots located in historic districts to other nearby lots in the community, we quantify the extent to which these lots attract less new construction activity. Finally, we examine whether residential soft sites, or lots built to less than half of their zoned capacity, are less likely to be redeveloped inside of historic districts. Soft sites create a unique opportunity for residential redevelopment, and our analysis investigates whether historic preservation affects the likelihood of this redevelopment.

Because historic districts tend to be concentrated in particular neighborhoods in the city, simple comparisons of density and development intensity between lots located inside of historic districts and those outside of them are likely to be misleading. These comparisons may simply capture differences between the high-density neighborhoods in lower Manhattan and downtown Brooklyn, where historic districts are concentrated, and other parts of the city. To provide a more accurate comparison, we instead compare lots inside historic districts to those lots outside of the district that are still located in the same general neighborhood, as measured by community districts. Community districts are sub-borough areas that include between 50,000 and 250,000 residents. By the end of 2014, 32 of the city’s 59 community districts housed at least one historic district. Each of these community districts also contained many unregulated parcels.4

Throughout the analysis, we estimate regressions for several measures, including lot density and development ratios. We include a dummy variable that identifies whether a parcel is located in a historic district, as well as community district fixed effects. With these fixed effects, the coefficient on the historic district indicator identifies whether, on average, the characteristics of lots located inside historic districts differ from those of lots located outside those districts, but still in the same general neighborhood.

4.4.A Sample

Throughout the analysis, we rely on shape-files provided by the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission. As of March 2015, these files identify the lots located within historic districts. We overlay MapPLUTO shape-files from the New York City Department of City Planning with the historic district maps to determine the land area of each lot covered by a historic district. Lots with less than 100 square feet of coverage by a historic district were not included within a historic district for purposes of our analysis. We exclude lots with a land use category of “09,” known as “Open Space and Outdoor Recreation,” as well as other lots classified as parks. We also exclude Ellis Island, Liberty Island, airports, large underwater lots, and lots with no calculated lot area.

We use the Zoning Resolution of the City of New York and the primary zoning district information on MapPLUTO 2007 to assign maximum residential and nonresidential floor area ratios (FAR) to each lot (and assigned FAR based on majority lot area coverage in the instances of a split zoning lot) as of 2007. Adjustments are made to the maximum floor area to account for special district regulations and as-of-right zoning bonuses (e.g., Inclusionary Housing Program and plaza bonuses).

For the regression analyses summarized in Table 4.2, we begin with a sample of 851,059 lots.5 From there, we exclude 1,154 New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) lots, 1,272 lots located in transfer districts, and 1,164 lots with individual or exterior landmarks. For the analysis of permitted floor area ratio, the final sample is 847,469 lots. For the remaining analyses in Table 4.2, we exclude lots designated as a historic district after 2004 because we are testing for differences in development patterns between 2004 and 2014 for parcels within and outside of historic districts as of 2004. This brings our sample to 838,963 lots. The sample used for the analysis of residential soft sites, which we report in Table 4.3, starts with lots as of 2007, makes the same exclusions, and is then restricted to 194,360 residential lots classified as soft sites in 2007.

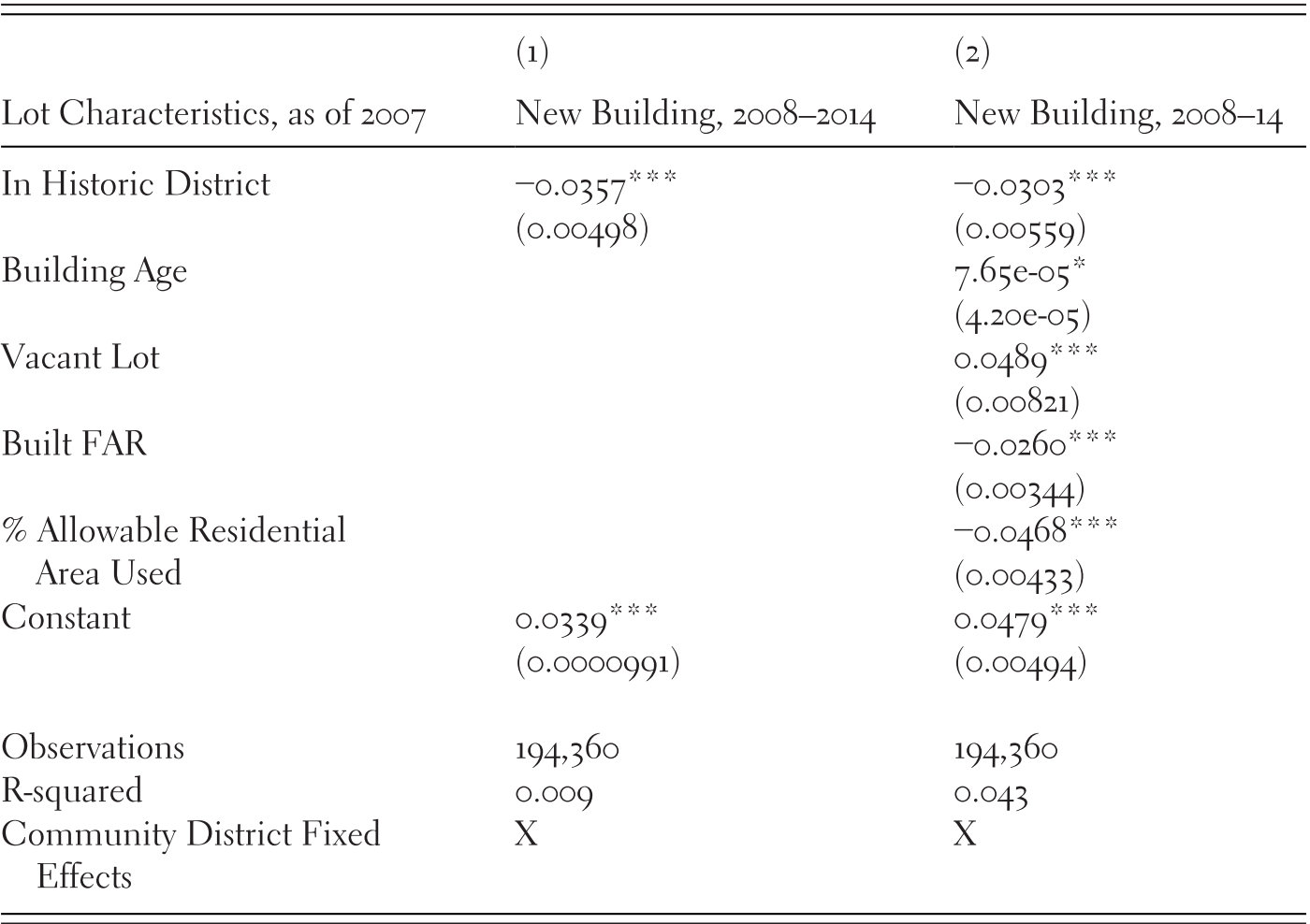

Table 4.2: Differences between a Historic District Lot and a Non-historic District Lot

| In New York City | In the Same Community District | |

|---|---|---|

| In the Share of Permitted Floor Area Used (2014) | 12.30 percentage points | 7.15 percentage points |

| In the Share of Lots with New Construction Activity (2004–2014) | ‒ 3.28 percentage points | ‒ 2.91 percentage points |

| In the Share of Lots with an Alt 1 Permit (2004–2014) | 4.03 percentage points | 0.48 percentage points (not significant) |

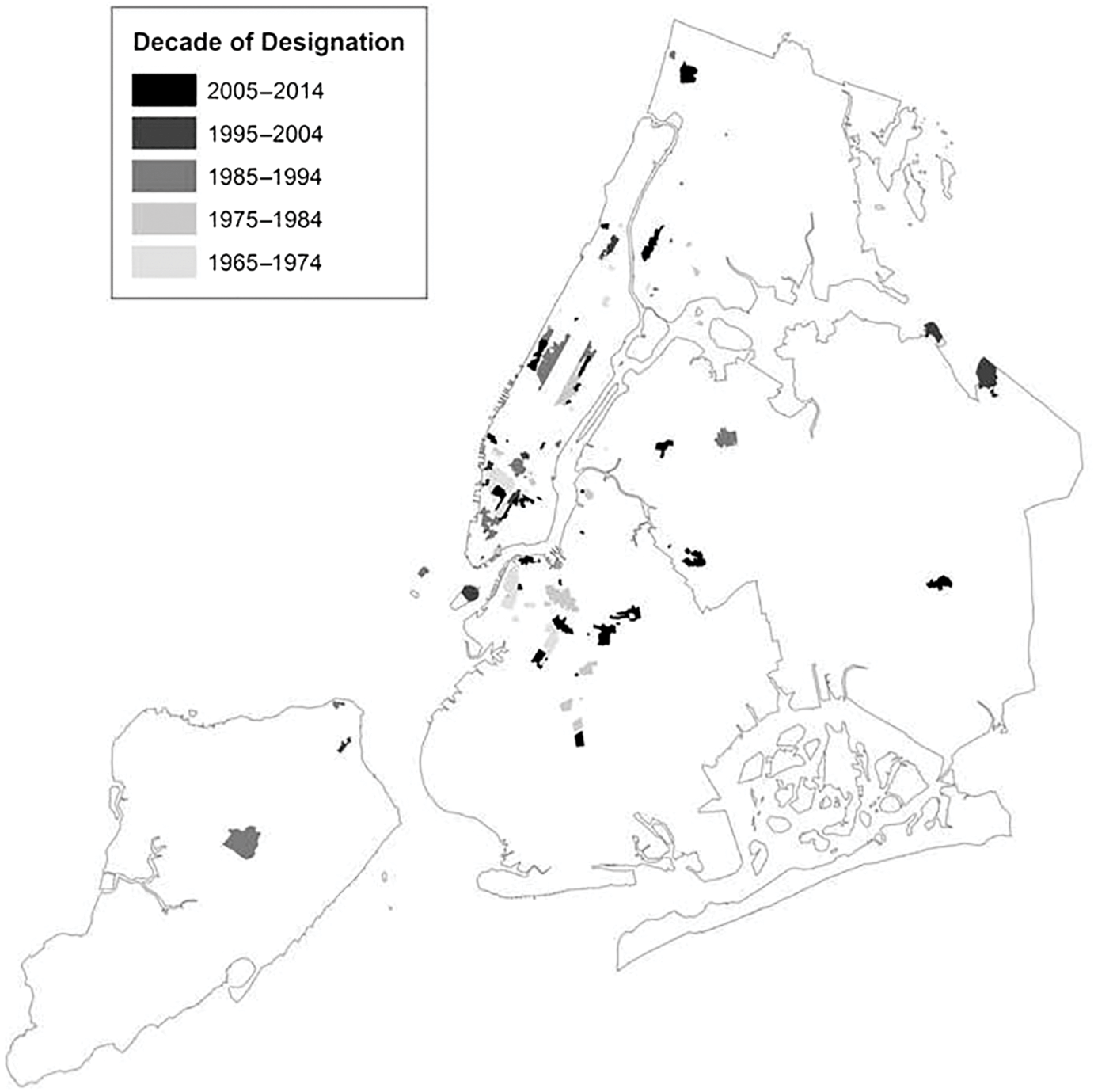

Table 4.3: Probability of 2007 Residential Soft Site Receiving a New Building, 2008–2014

| Lot Characteristics, as of 2007 | (1) New Building, 2008–2014 | (2) New Building, 2008–14 |

|---|---|---|

| In Historic District | −0.0357*** | −0.0303*** |

| (0.00498) | (0.00559) | |

| Building Age | 7.65e-05* | |

| (4.20e-05) | ||

| Vacant Lot | 0.0489*** | |

| (0.00821) | ||

| Built FAR | −0.0260*** | |

| (0.00344) | ||

| % Allowable Residential Area Used | −0.0468*** | |

| (0.00433) | ||

| Constant | 0.0339*** | 0.0479*** |

| (0.0000991) | (0.00494) | |

| Observations | 194,360 | 194,360 |

| R-squared | 0.009 | 0.043 |

| Community District Fixed Effects | X | X |

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

4.4.B Allowable and Built Density

We begin by simply comparing the built density levels of lots inside and outside of historic districts. As of 2014, we find that lots within historic districts were built to the same density as lots that were outside of these districts, but located in the same community district. Our first pass, then, suggests that historic districts might not do much to constrain density levels.

Rather than considering the built density of lots, however, an arguably better test is whether properties located in historic districts use less of their allowable zoning capacity than other nearby properties. Although this finding would not prove that lots in historic districts would be built to higher density absent their designation, it would suggest a constraint on the development process resulting from historic preservation. To identify the proportion of development capacity used on a lot, we divide the built floor area by the maximum floor area allowed on the lot.

The first row of Table 4.2 shows the difference in the share of permitted floor area used by lots inside and outside of historic districts. On average, we find that lots located inside historic districts utilize 12 percentage points more of their permitted floor area than other lots around the city. Citywide, the average lot within a historic district uses 59 percent of the permitted floor area. By comparison, the average lot outside of a historic district uses only 47 percent of permitted floor area. When we estimate our regressions with community district fixed effects, we find that this basic difference holds within community districts, but that the gap between lots located in historic districts and those outside of them shrinks: the initial gap of 12 percentage points from the citywide comparisons shrinks to just 7 percentage points when we make comparisons within the same community district. Both differences are statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

In short, as of 2014, our analysis reveals that owners of parcels in historic districts used more of their formal development rights than owners of other properties.6 In part, this is because historic districts are protecting properties that were built prior to the 1961 Zoning Resolution, which reduced allowable density levels throughout the city (New York City Department of City Planning). In historic districts, 98 percent of buildings were built before 1961 and nearly 9 percent of those pre-1961 parcels were built to density levels that current zoning would not allow. But going forward, the more relevant questions concern the likelihood that lots will be redeveloped in the future and that the development rights that technically exist in historic districts will be used. Thus, analyzing actual development activity within historic districts arguably offers a better test of the constraints imposed by historic preservation.

4.4.C New Construction and Alteration Activity

To analyze new construction, we examine whether lots located in historic districts by the start of 2004 were less likely to see new construction activity between 2004 and 2014 than other lots. The second row of Table 4.2 shows that lots in historic districts were, on average, just over three percentage points less likely to see new construction than other lots around the city. When we estimate a regression of new construction activity including community district fixed effects, we see that lots located inside historic districts were slightly less than three percentage points less likely to experience new construction compared to lots outside those districts but located in the same community district. These differences are both statistically significant. There are some notable outliers to this citywide average. For example, in the Tribeca North Historic District, 10 percent of lots saw new construction activity during this 10-year period. On the other hand, more than half of districts – 52 in total – reported no new construction activity between 2004 and 2014.

Finally, the third row of Table 4.2 shows differences in the share of lots that received alteration permits approving building renovations. We focus on Alteration 1 permits, which include a change in the Certificate of Occupancy. When we compare citywide differences, the results show that lots in historic districts were more likely to receive alteration permits than lots not regulated by the LPC. However, this difference goes away (or loses statistical significance) when we estimate a regression to account for differences across community districts. In other words, historic districts were no more or less likely to receive alteration permits than other nearby lots.

While these analyses show that lots inside of historic districts are less likely to see new construction than other nearby lots, these findings do not control for the likelihood of redevelopment or new construction before historic district designation. It is possible that historic districts are designated in areas where little new construction would take place even absent the designation. In previous research, we find that although new construction is less common on sites within historic areas than on other sites, even before they are designated as districts, the district designation widens the gap (Been et al. Reference Been, Ellen, Gedal, Glaeser and McCabe2016). In other words, following designation, sites within historic districts are significantly less likely to see new construction than they were before designation, even after controlling for development trends in the surrounding neighborhood.

4.4.D The Development of Residential Soft Sites

Finally, we consider the development of residential soft sites, or lots built to less than half of their permitted development capacity under current zoning regulations.7 Because these sites are substantially underbuilt relative to the allowable density under existing zoning regulations, they are prime locations for redevelopment. In this section, we explore whether such residential soft sites are less likely to be redeveloped when they are located within historic districts.

Across New York City, 19 percent of lots located in historic districts were soft sites in 2007 compared to 22 percent of lots located outside of those districts.8 To test whether these sites are less likely to be redeveloped when they are located in historic districts, we estimate a regression of the probability that a 2007 soft site was redeveloped, or a new building was constructed on it, between 2008 and 2014.9 We control for several features of the lot, including whether the site is vacant, the share of allowable density used, and the age and size of any existing building. With these controls, we can test whether buildings of a similar size, age, and allowable zoning capacity were less likely to be redeveloped when they were located in a historic district. We also include community district fixed effects to control for the local neighborhood.10 Our key independent variable is whether the parcel is located in a historic district as of 2007.11 Our analysis is reported in Table 4.3.

Consistent with our expectations, we find that vacant lots are substantially more likely to be redeveloped than lots with existing buildings. Lots with structures built more recently, as well as those with larger buildings and buildings that use up more of their allowable development rights, are less likely see new construction. Critical for our analysis, we find that after controlling for these factors, soft sites located inside a historic district are significantly less likely to experience new construction than those located outside of a historic district. The owners of soft sites are less likely to redevelop their lots when they are located in historic districts.

While in the short run, these differences are not likely to radically alter the course of development, in the longer run, they might. Historic districts have locked up quite a bit of floor area in New York City, or at least made it more difficult to develop. In 2014, we estimate, roughly 119 million square feet of allowable residential floor space was unused on privately owned lots in historic districts, based on built density and currently allowable floor area ratios. This translates into roughly 119,000 housing units. To be sure, these units would not immediately (or necessarily) be built absent historic district designation, and there may be other zoning constraints present that make it impossible to build to the maximum allowable floor area ratio. Historic districts constrain density only to the extent that development is unconstrained by other regulatory tools. However, our results show that this “allowable” residential square footage would be more likely to be built in the absence of designation.

4.4.E The Cost of Supply Restrictions

Our analysis reveals that while lots in historic districts are not built less densely than other lots today, they are likely to see less new construction, and therefore add less density, in the future. Such supply restrictions have several implications. First, we expect these restrictions to increase prices and rents. In neighborhoods designated as historic districts, Been and colleagues (Reference Been, Ellen, Gedal, Glaeser and McCabe2016) report localized property value increases following the designation of historic districts. These price changes are concentrated in neighborhoods in the outer boroughs where the lost option to redevelop is high. However, the establishment of historic districts is also likely to constrain overall development in the city, especially as additional districts are added.

It is difficult to quantify this more generalized impact of preservation on citywide prices. Identifying a citywide counterfactual – for example, a similarly high-cost city without preservation efforts – is impossible. And while we expect preservation efforts to contribute to skyrocketing prices by restricting the supply of housing, we expect these supply constraints are not among the most important explanation for rising prices and rent inflation across New York City. Many other factors contribute to rising prices and rents in the city, including the strong economy of the city, the enduring popularity of New York as a place to do business, the limited supply of land, and the many other restrictions on building activity in the city (Salama et al. Reference Salama, Schill and Springer2005). Beyond concerns about increasing prices and rents, it is possible that these supply restrictions could limit overall economic growth in the city. Workers may demand higher wages to afford the cost of living in the city, and businesses untethered to the economy of New York City may choose to leave the city for places with cheaper housing and an ample supply of workers.

Finally, supply restrictions that result from historic preservation are likely to exacerbate patterns of economic segregation in urban neighborhoods. In the decades following historic designation, neighborhoods experience increased polarization as poverty rates decline and neighborhood incomes climb within districts (McCabe and Ellen Reference McCabe and Ellen2016). It appears that the supply restrictions imposed by historic preservation are attracting high-income households who value the amenities of historic neighborhoods and are willing to pay a premium to live in these aesthetically appealing, high-status neighborhoods.

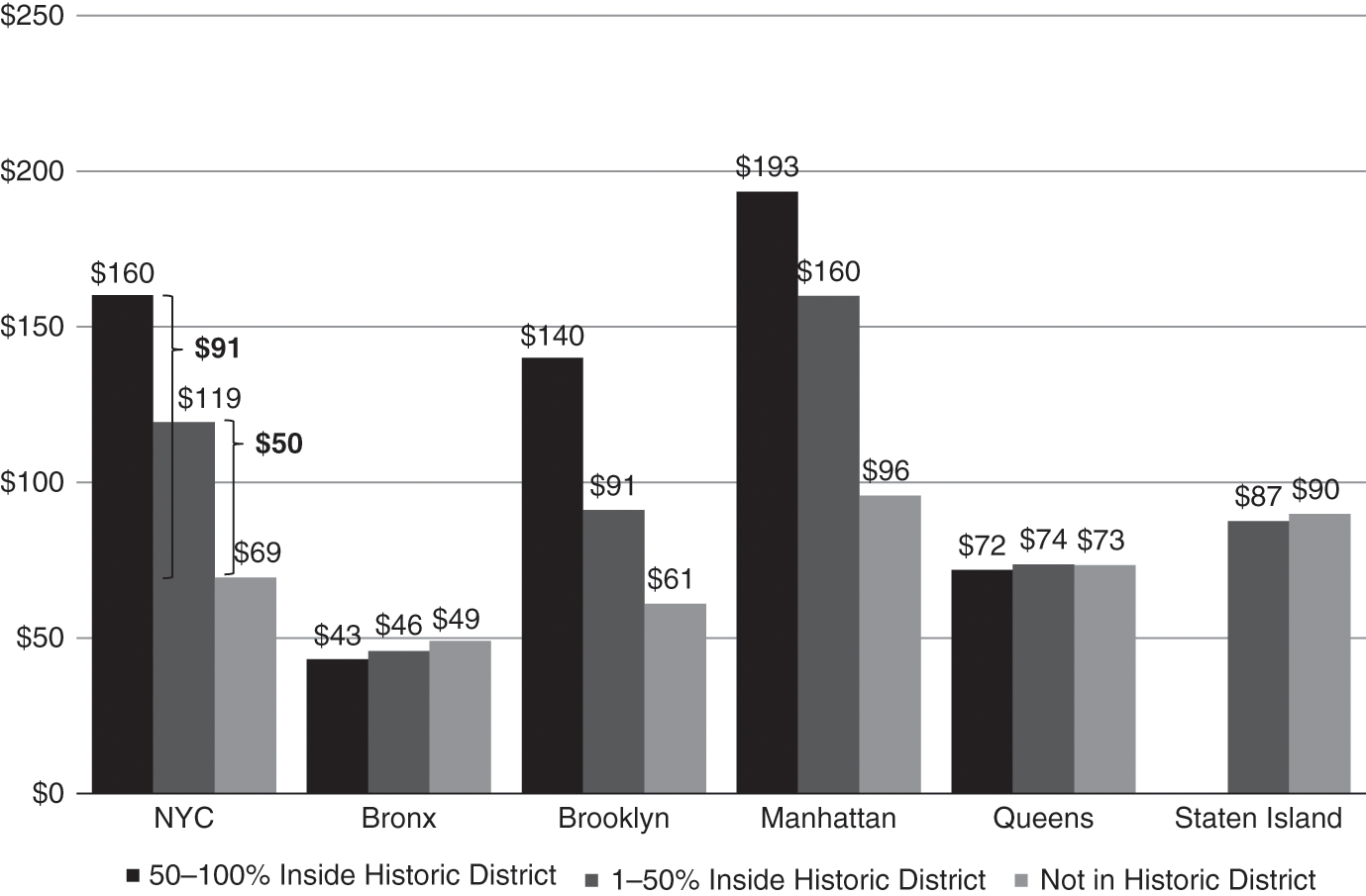

These patterns of economic segregation are increasingly evident in neighborhoods regulated through the historic preservation process. By 2012, the composition of neighborhood residents living in New York’s historic districts was substantially different than the composition of residents outside of them. In Figure 4.3, we compare the average household income in census tracts with at least half of their lots located in a historic district to tracts with fewer than half of their lots in historic districts and tracts located completely outside of those districts. The average household income in census tracts comprised mostly of lots within a historic district was $160,192 – more than twice the income of neighborhoods entirely outside of districts.12 These differences, which are driven by Manhattan and Brooklyn, result from both initial differences between neighborhoods and the actual impact of historic preservation.

Figure 4.3 Average Household Income (in Thousands) for Census Tracts by Historic District Coverage, 2012

Beyond these variations in average income, we find other substantial differences between the population living within historic districts and the comparable population living within the same community but outside the district boundaries. The poverty rates in census tracts made up mostly of historic districts are significantly lower than the rates in nearby tracts within the same community district, and the share of the population with college degrees is substantially higher.

4.5 Policy Responses

By offering a more nuanced account of the costs and benefits of historic preservation, this chapter invites a rethinking of the preservation process in New York City. To be clear, we are not questioning the designation of any existing historic districts, nor are we advocating for the active preservation community in New York City to curtail their efforts to protect the historic fabric of the city. The Landmarks Preservation Commission, in collaboration with countless advocates and allies, has preserved many historically important buildings and neighborhoods, contributing to the richness of the city that attracts visitors and residents alike. Instead, our analyses are intended to highlight that historic preservation does not come without costs. Preservation limits opportunities for redevelopment and, in doing so, constrains the supply of housing in the city.

Currently, the process for designating historic districts in New York City does not allow for deliberate consideration of the full range of costs associated with designation. Because the Landmarks Preservation Commission is tasked with preserving the rich historic assets of the city, it does so with limited consultation from other agencies. The Department of City Planning and the City Council are formally brought into the process only after approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. As such, the current process does not allow for a rigorous balancing of the goals of preservation against other planning goals, including efforts to develop affordable housing. Although officials from the Landmarks Preservation Commission present the district at a public hearing at the City Planning Commission following LPC approval, the City Planning Commission has no power to amend the proposal before it goes to the City Council. Indeed, although the Commission can recommend modifications to the proposal (e.g., the removal of particular properties), in practice, it typically just forwards the approved district along to the City Council.

Similarly, the City Council reviews LPC designations, but the process is an administrative rather than a legislative action. As a result, the Council is constrained in its ability to reject or modify historic designations, as it can only make decisions based on the administrative record and cannot take other considerations into account. In practice, the City Council has approved all proposed districts with only minimal changes.

Several reforms could allow policy makers to weigh a broader set of benefits and costs. First, New York City’s preservation decision-making process could be restructured. In some cities, like Baltimore and Chicago, historic preservation officials sit within the city planning agency, allowing for greater coordination and consideration of broader planning goals in historic preservation decisions. Similarly, in Washington, DC, the Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB) – the city’s comparable agency to New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission – is incorporated into the Office of Planning, ensuring that the goals of historic preservation are considered within the planning process. The mayor of Washington, DC, also appoints a special agent for historic preservation to help adjudicate conflicts about development in historic districts, including conflicts about whether the demolition of buildings within historic districts can be permissible on a case-by-case basis to strengthen other goals of the planning process. The agent can decide if the city should issue a building permit for projects deemed of “special merit,” or if the failure to do so would result in “unreasonable economic hardship to the owner.” This process creates the opportunity for an independent assessment that weighs the benefits of preservation against other goals of the city-planning process. While there is no guarantee that such an agent will be balanced in his or her assessment, this process at least offers the potential for an additional independent voice in this politically charged process.

While it is hard to imagine adopting these approaches in New York City, given the size and history of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, it is worth considering other ways for the designation process to meaningfully consider potential adverse impacts. One alternative would be to create a process that requires formal comment from the City Planning Commission prior to an LPC vote of designation. This would bring the City Planning Commission’s expertise on zoning, development patterns, and broader planning goals into the designation process. Indeed, city law could require that the Department of City Planning issue a report describing the effects of historic designation on residential development. These reports could include a “Housing Impact Statement” that would estimate the number of potential housing units (or residential square footage) that could no longer be built as-of-right following the designation of a proposed district. This calculation is surely imperfect; for example, it merely suggests the amount of residential square footage that is locked in or hindered given current zoning. Still, with this information, the City Council could be better armed to weigh the benefits of preserving historic assets against a more complete assessment of the costs of preservation. Public disclosure of the supply restrictions that the preservation process imposes would create a more balanced process that considers the costs of historic designation alongside the many benefits.

Once the debate surrounding a historic district designation includes consideration of the impact on housing supply, there might be greater pressure for the City Council to seek mitigation measures for the adverse impact. A mitigation could include an effort to upzone nearby areas to preserve the total amount of residential capacity. City officials might also consider supporting the creation of affordable housing in newly designated historic districts to mitigate the potential effects on localized housing prices and rents.

In addition, New York City’s historic district regulatory framework could permit as-of-right development activity on vacant sites and noncontributing buildings within historic districts. While anecdotally, the LPC attempts to keep such sites outside of historic districts when sites are on the periphery of a proposed district, there are many instances where vacant and noncontributing structures are included. The uncertainty regarding development on those lots increases the risk and cost associated with investing in new housing within historic districts.

The city might also reconsider the review process for noncontributing buildings within historic districts. New York City could follow Washington, DC, and Philadelphia’s example and specifically identify which structures are noncontributing in order to provide greater certainty regarding redevelopment opportunities of noncontributing sites. While the owner of a vacant lot knows that her lot can be developed within a historic district pending design review by the LPC, an owner of what appears to be a noncontributing building does not currently have certainty that the LPC will permit redevelopment.13 Policy could be modified so that designation reports explicitly identify noncontributing structures and permit owners to demolish such structures without any further LPC review. While the design of a new building would still be subject to LPC review through the Certificate of Appropriateness approval process, owners would have greater certainty about the potential for redevelopment. This might facilitate increased investment in new construction within historic districts.

To go one step further, New York City law could be amended to provide for an as-of-right framework for new construction on vacant and noncontributing sites. While the Certificate of Appropriateness approval process for new construction currently requires public review and a Commission-level review, one could imagine a designation report detailing design guidelines for new construction on developable sites. As long as a developer met clear design guidelines as certified through a ministerial LPC staff-level review, the Department of Buildings would issue permits for new construction. If a developer sought to construct a building with an alternative design, the developer would still have the ability to go through the typical Certificate of Appropriateness review process.

4.6 Conclusions

In New York City, the Landmarks Preservation Commission plays a critical role in preserving the unique history of the city through the designation of historic neighborhoods and individual landmarks. Protecting the architectural integrity and cultural significance of urban neighborhoods offers an array of benefits to residents of designated neighborhoods and the city as a whole. The iconic buildings of New York help to attract millions of tourists each year, and the streetscapes of neighborhoods like Harlem, Greenwich Village, and Brooklyn Heights attract highly skilled workers who contribute to the economy of New York City. The designation process keeps alive the unique and rich history of the city. Although many of these benefits are difficult to quantify, they should not be undervalued in any assessment of the place of preservation.

But while affirming the benefits of preservation, this chapter serves as a reminder that historic preservation, like other land use regulations, imposes costs by restricting development. To be sure, historic preservation is just one of many regulations that limits opportunities for redevelopment and new construction. Indeed, our findings suggest that lots in historic districts are built at comparable densities to those of others nearby, in part because historic districts generally protect buildings that were developed at a time when the city’s zoning code was more lenient.

However, our analysis suggests that the creation of historic districts is likely to constrain the development and supply of housing in the future. Residential soft sites located in historic districts are less likely to see redevelopment activity compared to nearby soft sites outside of the district. More generally, lots located in historic districts experience less new construction relative to nearby lots that are not regulated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. And significantly, this gap in construction activity is heightened after historic districts are designated. These findings suggest that historic preservation is likely to restrict the supply of housing going forward. These costs of preservation must be balanced against the benefits of preserving the historic assets of the city. An integrated process that incorporates preservation goals into the broader planning process would ensure that the costs and benefits of historic preservation are more adequately assessed in New York City.

Authors’ Note

We would like to thank Eric Stern for his excellent research assistance with this chapter.

Land’s permanence is also what makes land unique. Every spot on earth has a past and an enduring future, and those attributes spark human curiosity about any given spot’s significance. This dynamic plays out when people are considering where to live, where to shop, where to work, or where to spend their leisure time. And history is frequently a selling point.

For example, at a picturesque country club in Sterling, Virginia, a solemn stone marker commemorates the scores of Civil War soldiers who died at a Potomac River crossing. A lovely plaque, installed on a riverside boulder, reminds golfers and passersby that “Many great American soldiers, both of the North and South, died at this spot. … The casualties were so great that the water would turn red and thus became known as ‘The River of Blood.’”

There is one small problem with the River of Blood monument. There is no historical evidence suggesting that any soldiers were killed at the spot in question. The closest known Civil War battle occurred 11 miles away. The River of Blood tale appears to have been concocted by the country club’s namesake, who insisted that “numerous historians” had told either him or his people (accounts varied during a single conversation with a reporter) that the golf course was built at the site of a river-crossing conflict. So the dubious plaque remains, near the fifteenth tee at the Trump National Golf Club (Fandos Reference Fandos2015).

A natural first instinct upon hearing of this apparent fabrication is recoil. There is something troublesome about an inauthentic stone marker and the tale underlying it. Perhaps a false marker like this one leaves people confused about history they ought to understand or makes people mistrust the historical memorials at sites of genuine bloodshed. What motive would someone have to lie about such a thing? It isn’t obvious that consumers demand golfing opportunities where the players must avoid the river in order to spare themselves guilt over desecrating a battlefield, to say nothing of a one-stroke penalty.

And yet, of all the lies Donald Trump has told, this seems a rather harmless one. There were certainly plenty of Civil War soldiers who did die near the Potomac, even if none of them fell anywhere close to the fourteenth green. Perhaps the stone marker piques the curiosity of some caddies, and sparks their own research into the war. Or it causes a golfer to reflect on the life of a great, great grandfather, who really did die during America’s bloodiest conflict.

This story about the River of Blood implicates a broader question. Is authentic history, in the hands of imperfect human institutions, superior to the kind of fake history commemorated at the Trump National Golf Club? With reluctance, the author has tentatively concluded that the answer is “not by much.” When society presents authentic historical facts to present generations, especially in a manner tied to historical markers in physical space, it often does so in a manner that is so selective, so simplified, or so beholden to contemporary preferences that its value over contrived history appears to be marginal. At the same time, the costs of historical preservation can be quite significant. Societies that prompt private property owners to preserve their property in a particular way either substantially constrain what owners can do or devote substantial financial resources (via tax incentives, typically) to inducing forms of past-preservation in which many owners would not otherwise engage. Contrived history is cheap and voluntary. “Genuine” history is expensive and often needs to be compelled. Against that backdrop, this chapter will reconsider an implicit premise in American constitutional law that is now decades old – the idea that there is a strong state interest to compel the preservation of historic property.

Along the way, this chapter will also examine previously ignored aspects of fake history and historic preservation. Real estate developers who embrace contrived history can send powerful signals to would-be residents about who is welcome in a particular community. Choices about how to construct a community’s mythology may influence who decides to settle there. A new community in Florida has embraced Trump-style fake history with gusto, albeit with an occasional admission of the narrative’s fictitious nature. That same community also happens to be one of the most racially segregated places in the United States. This correlation is perhaps not coincidental. And to the extent that the segregation arises by design, the success of that strategy in Florida should alert us to the possibility that more traditional forms of historic preservation, which selectively highlight some aspects of a built environment’s past while ignoring other parts of a community’s history, can also promote residential homogeneity.

Comparing the phenomenon of fake history to traditional historical preservation efforts in cities may help us understand previously underemphasized implications of historic preservation regulation and fair housing laws. Part 1 of this chapter begins with a case study of The Villages, the Florida community in question. Drawing on scholarship from geography and other fields, it shows how the tendency to concoct, embellish, or distort a community’s history is widespread and exists in a great many cultures. Part 2 then examines the costs and benefits of historic preservation requirements in the United States, and Part 3 reviews the Supreme Court’s landmark decisions in Berman v. Parker and Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City.

5.1 Fake History in The Villages and Elsewhere

The Villages, Florida, is an interesting residential community from a social scientific perspective. Four things stand out about The Villages. First, in percentage terms, it is the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the United States (Fishleder et al. Reference Fishleder, Schonfeld, Corvin, Tyler and VandeWeerd2016). Second, it is evidently the largest age-restricted community in the United States (Ness Reference Ness2013). Third, The Villages is strikingly homogenous with respect not only to age but to other demographic dimensions as well. Although it is located in a very diverse state, less than one percent of its residents are African American and barely more than one percent of its residents are Latino (Fishleder et al. Reference Fishleder, Schonfeld, Corvin, Tyler and VandeWeerd2016; U.S. Census Bureau Villages CPD 2016). The nearest large city, Orlando, is an hour’s drive from The Villages, and its population was 28 percent African American and 25 percent Latino in the 2010 census (U.S. Census Bureau Orlando City CPD). The Villages is therefore one of the whitest parts of the United States. Several other large retirement communities in the United States are also overwhelmingly Caucasian, but not to the extent of The Villages.1 Finally, The Villages sports thousands of clubs for residents and an abundance of social capital.

The Villages is a collection of numerous gated communities, each with its own swimming pool and community center. Nearly all of the homes in The Villages are single-story, with a collection of ranch-style, single-family homes and townhouses. Home prices typically range from the $200,000s to the $600,000s. The Villages population in 2010 had an adult labor force participation rate of just 15 percent, according to the Census Bureau, suggesting nearly universal retirement. Economic life in The Villages is organized around three pedestrian- and golf-cart-friendly “downtowns,” each of which has its own movie theater, bars, restaurants, and shops, all catering to the community’s elderly residents. These downtowns are not gated and attract some residents from outside the development. Restaurants tend to be very busy at 5:30 p.m. and largely empty by 7:30. Music is piped into the downtowns from omnipresent speakers, occasionally interrupted by news bulletins from Fox News. Republican presidential candidates run very well ahead of their Democratic counterparts.

The Villages began, rather ignominiously, in 1982, when Harold Schwartz purchased a mobile home park in a rural part of Florida between Orlando and Ocala (Bartling Reference Bartling, DeHaene and De Cauter2008). During the 1990s, Schwartz took advantage of a Florida-specific institution called the Community Development District, which permitted large-scale real estate developers to form their own quasi-municipal governments that could levy taxes and issue tax-favored bonds to raise money for community infrastructure (Bartling Reference Bartling2007). Schwartz and his son, Gary Morse, then acquired large swaths of land surrounding his mobile home park, land previously occupied by watermelon farmers and ranchers, with plans to quickly grow the population from nothing to 100,000 people by 2020. The Villages’ development proceeded ahead of schedule; its population actually reached 110,000 people by 2014 (Olorunnipa Reference Olorunnipa2014).

Given its very recent formation, the extreme racial homogeneity found among The Villages’ population is stunning. Some municipalities that are similarly overwhelmingly Caucasian, like Mentor, Ohio, have been in existence since the eighteenth century. Over generations, patterns of racial segregation can persist and can affect the residential location choices of subsequent potential homebuyers. Neighborhoods known to be overwhelmingly white signal African American buyers to exclude themselves (Boddie Reference Boddie2010). But The Villages was founded in a very diverse part of the country during an era in which the Fair Housing Act was already on the books. So the mechanisms by which this extreme racial homogeneity arose are less blatant.

The Villages is largely a company town. The Morse family initially owned all the residential and commercial real estate, as well as all 42(!) of the golf courses, and other recreational amenities. The development generated $9.9 billion in revenue from 1986 to 2014, enabling the Morses to amass a $2.9 billion family fortune (Olorunnipa Reference Olorunnipa2014). Morse-owned entities contracted with one another, often obligating The Villages homeowners to pay assessments that covered the costs of the golf courses and other amenities (Bartling Reference Bartling2007).

A visitor to any of The Villages’ three downtowns will quickly notice their distinctive retro theming. Mediterranean architecture pervades Spanish Springs, Lake Sumter Landing is designed to look like a Florida beach town set alongside a large, manmade lake, and Brownwood brings to mind an Old West cattle town out of West Texas or Arizona. No structures in any of the downtowns clash with the towns’ respective themes, and the developers went to great lengths to evoke a particular era, mood, and place in each of the downtowns. There is not a single example of modern architecture to be found, and yet all the downtowns are essentially new. Nor are there any residences in the downtowns. Those single-story homes are all a car or golf-cart ride away, providing residents with the sorts of low-density residential suburban sprawl that they became accustomed to before moving to Florida and the sorts of walkable commercial spaces that new urbanists favor (Rybczynski Reference Rybczynski2010).

Fake history is omnipresent throughout The Villages’ downtowns. The Villages’ developer “hired a design firm [Forrec] with experience working for Universal Studios to invent this make-believe town, including its history, customs, and traditions” (Blechman Reference Blechman2008). Newly constructed buildings sport fake “Established 1792” signs. There are phony disused railroad tracks with an old caboose in the Lake Sumter Landing town center, and faded (but not too faded) “ghost advertisements” for old movies or for the saddle sellers of yore who purportedly occupied a building now occupied by a different commercial tenant. Plaques in front of numerous downtown buildings weave complex tales of adventure, successes, setbacks, and betrayals, introducing numerous fictitious town founders and other characters. There are 56 fake history plaques scattered through the three downtowns, with 16 in Brownwood, 8 in Spanish Springs, and 32 in Lake Sumter Landing.2 The widely read local newspaper has featured quizzes that test residents about the community’s fake history (The Villages Daily Sun 2016).

Perhaps the developers’ most self-referential bit of fake history is a recently installed text at “Paddock Square,” the social hub of the newest downtown in Brownwood, where music is performed nightly. An impressive bronze plaque tells the story of the place:

The central plaza of Brownwood is now known as Paddock Square. Once slated for demolition, its historic value was championed by a group of visionary citizens in the 1950s. Today it contains remnants of the earliest roots of the town from its days as a cow camp used by legendary Cracker K. O. Atlas. The original Atlas dog-trot cabin has been relocated here, within the perimeter of what was once the original corral of the Atlas Ranch. Numerous buildings from the earliest days of the settlement, including K. O. Atlas’s barn and bunkhouse, still surround Paddock Square.

The grandstands were built in the 1880s to accommodate crowds who came to Paddock Square to attend rodeos staged by William G. Brown after he purchased the Atlas Ranch in 1879. Subsequent city leaders found these raucous gatherings too disruptive to downtown business and later moved the popular events downwind of the town center. The grandstands were left intact and used as seating for civic and theatrical events well into the next century.

Brownwood and Paddock Square opened to the public in 2012 (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2013). The land on which Paddock Square was built was most likely a watermelon farm in the 1880s and the 1950s (Blechman Reference Blechman2008). Another noteworthy plaque refers to an Ebenezer Matthews, whose “dislike of young people was a well-known fact in the community” and who became the target of various practical jokes by local high school students as a consequence. Although Matthews is in that sense the patron saint of a community with no resident children, the historical origins of The Villages’ prohibition of child residents is explained on none of the downtowns’ 56 plaques.

Notwithstanding the developers’ efforts to erase and replace it, the “real” history of the land The Villages now occupies is interesting. As Amanda Brian points out, there was indeed a cattle industry in nineteenth-century Florida (Reference Brian2014). At the conclusion of the Seminole Wars, native tribes were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands to make way for white cattlemen. The bloody Seminole Wars raged on for decades, and these wars would have provided an interesting backdrop for an alternative fake history of the Villages. Yet the Seminoles and other indigenous Floridians go completely unmentioned in all of the 56 fake history plaques that grace Spanish Springs, Lake Sumter Landing, and Brownwood.3 Indeed, among all of these plaques, two plaques reference possibly Latino residents4 – both of these involve the same nuclear family (the Sanchez family) – and no plaques feature apparent references to any other individuals who weren’t of European ancestry.5 The fictitious story told in The Villages is therefore an overwhelmingly European American narrative, and it would not be surprising if stories about The Villages’ past function as “exclusionary vibes” that influence the residential composition of The Villages’ present (Strahilevitz Reference Strahilevitz2011). Under this strategy, The Villages’ architecture, fake history, marketing choices, and initial population uses language and imagery to establish a focal point that attracts white homeowners and repels nonwhite homebuyers. It quickly becomes known as a place where homeowners seeking racial homogeneity can find one another. Traces of African Americans’ historic presence in The Villages have been wiped out too. Included within The Villages is an African American Baptist cemetery that predates the community’s status as an age-restricted community. Strategically placed hedges and bamboo plantings render it invisible from the neighboring homes (Brian Reference Brian2014).

There are plausibly larger factors at play too. Older Americans are whiter than younger Americans, and among seniors whites are more likely to be able to afford homes in retirement communities that are beyond the reach of seniors without substantial savings. Beyond that, dozens of golf clubs are part of The Villages, and all homeowners pay for access to most of these clubs via their monthly assessments. (Residents wishing to play on a handful of “championship” courses have to pay an additional membership fee.) Given that for much of The Villages’ residents’ lives golf was the most racially segregated mass participation sport in the United States, one would expect that The Villages would be particularly appealing to Caucasians and particularly unappealing to African American and Latino retirees. Prospective Caucasian homeowners would be more likely to purchase homes in The Villages than African Americans, and even Caucasian buyers who play no golf might be willing to play a premium to live among the overwhelmingly white residents who are attracted to mandatory membership golf communities. “Exclusionary amenities,” like exclusionary vibes, thus seem pervasive in The Villages, and they may well trigger the same segregation-promoting dynamics. An exclusionary amenity is a costly club good that is embedded in a residential community where all residents must pay for it. Willingness to pay for that amenity becomes a proxy for race or other demographic factors (Strahilevitz Reference Strahilevitz2011). It is plausible that The Villages’ exclusionary vibes and exclusionary amenities reinforce each other, though identifying the causal relationships and magnitudes is a tall order.

That said, something else important seems pervasive in The Villages too: happiness. In a health survey sent by academic researchers to all identified residents of the community, one that generated a very high 37.4 percent response rate, residents of The Villages expressed extraordinary satisfaction with their lives in the community. Fully 90.8 percent of The Villages’ residents surveyed rated their satisfaction with life in The Villages as an 8, 9, or 10 on a 10-point scale (Fishleder et al. Reference Fishleder, Schonfeld, Corvin, Tyler and VandeWeerd2016). Although any comparison to a baseline will raise problems about representative income levels, senior citizens nationally are much less likely to report such high levels of satisfaction (Strine et al. Reference Strine, Chapman, Balluz, Moriarty and Mokdad2008).

While residents’ high satisfaction in a racially homogenous community is in many respects unfortunate, racial segregation among seniors is probably less harmful to society than racial segregation among younger Americans.6 Residents of The Villages lack school-aged children, so segregation there isn’t contributing to school segregation. And residents are mostly involved in economic life only as consumers, so the segregated nature of their local social networks probably does not prevent people of color from enjoying access to employment-related economic opportunities. The racial segregation of Americans in their twenties, thirties, forties, and fifties is more pernicious.

To be sure, The Villages’ fake history itself is unlikely to play a large role in explaining why its residents express such high levels of satisfaction with their surroundings. At least in the short term, the racial homogeneity of The Villages could be itself an alternative explanation for aspects of the community like its high levels of generalized trust and social cohesion (Putnam Reference Putnam2007). Yet the available data are hard to square with the proposition that presenting community residents with a contrived and phony version of the history of a place significantly undermines residents’ subjective well-being. And data from other researchers suggest that some survey respondents prefer fake historical architecture to modernist contemporary architecture, though there are legitimate questions about the external validity of this data (Levi Reference Levi2005).

Given this satisfaction, it is worth asking why The Villages’ model has not been replicated more widely. Indeed, perhaps it is only a matter of time until residential life modeled on theme park visits becomes the norm. Given the success and consumer appeal of The Villages, it is easy to imagine real estate developers embracing fictitious, built-environment narratives in a manner that is more expensive (because of licensing fees) but has ready-made cultural resonance. Millennial retirees might want to live in a retirement community that looks precisely like Hogsmeade or King’s Landing. In such a community, the residents are likely to know the built environment’s “historical” narrative well, to care about it, and to view it as central to the community’s identity. Can Lancaster, Pennsylvania’s, or Akron, Ohio’s residents say the same thing?

The discussion so far has taken Villagers’ preferences for granted, but it is worth noting, at least in passing, that audiences where this chapter has been presented inevitably want to understand or critique their embrace of fake history. These audiences regard what is happening in The Villages as creepy, though the basis for their intuitions vary widely. Perhaps the concern is that fiction has so thoroughly and self-consciously displaced fact – maybe residents embrace this concocted history to assuage subconscious guilt about their having left communities in which they were rooted as adults. Alternatively, maybe what’s jarring is that the community seems to be one where “play” has become a full-time pursuit for the residents, crowding out other important values associated with ordinary life (Hurka and Tasioulas Reference Hurka and Tasioulas2007). It could be instead that by trying to create a planned version of a community that grew and changed organically the community is subtly but powerfully missing important aspects that make it human (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1961). Or maybe the clear racial and evident political homogeneity in The Villages produces a kind of echo chamber among residents that may adversely affect political discourse among a population who vote in very large numbers. Finally, the strategies used in The Villages resemble those employed by authoritarian regimes, which sometimes go to great lengths to present their citizens with a narrative about the built environment’s past that serves the contemporary aims of the leadership class (Johnson Reference Johnson2016).

On the other hand, to Villages residents, the ability to play in a community that caters to their needs, that is designed specifically for people like them (with golf cart paths, ample public restrooms downtown, easily readable signs, and restaurants that open early for dinner), that doesn’t regard their aging as embarrassing, and that provides them the opportunity to focus on consumption after a lifetime of working, parenting, and saving seems appealing. Residents might pointedly ask what gives us the right to judge them and the way they have chosen to retire. They have paid their dues, and perhaps when we reach their life stage, we will want something similar.

All of this discussion raises some hard questions that will be pursued in the remainder of this chapter. First, is there inevitably such a thing as “genuine history” that we can contrast with The Villages’ contrived history? And relatedly, do we have reason to believe that fake history is more likely to promote the troubling forms of segregation that have arisen in The Villages? Finally, and subversively, what if Villages-style fake history is a perfectly adequate (but much more affordable) substitute for “genuine” history? That is, if satisfying some abstract preference for authenticity entails limiting how current owners can use and modify their property by requiring owners to comply ex ante with a zoning or covenants scheme that requires conformity with a broadly applicable theme, are the limits justifiable? Preserving old buildings can be a very costly endeavor, particularly when hazardous substances like lead paint or asbestos were used in its initial construction. In some extreme cases, governments force building owners to maintain structures that are not economically viable (J. C. & Associates 2001). Is the game worth the candle?

5.2 Is All History Fake History?

There is a school of thought that questions whether the presentation of a community’s genuine history is a realistic possibility in human society. David Lowenthal is most famous for the claim that “the past is a foreign country.” In Lowenthal’s view, so many of the objects contemporary society preserves represent a distorted picture of life in the past. Worse, the story is often distorted in the present precisely so that the narrative can be placed in the service of contemporary needs and wants (Reference Lowenthal1999). Ada Louise Huxtable called historic preservation a “semantic trap,” something different only in degree from fantastical communities like Disneyland or Seaside, Florida (Reference Huxtable1997). Ethnographic studies of revitalization efforts, such as Jeremy Wells’ assessment of historic preservation efforts on Anderson, South Carolina’s Main Street, identify a common theme of local stakeholders embracing efforts to create a kind of “spontaneous fantasy,” with the local architecture reflecting an aspirational account of what life on the main thoroughfare should have been like during the town’s earlier days (Reference Wells2010).

As we survey the way that historical sites and buildings are preserved, the arbitrariness of what successor generations decide to emphasize, ignore, embellish, and conceal stands in sharp relief (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1998a). Nineteenth-century Americans bemoaned the fact that the precise spot where the Pilgrims disembarked in 1620 was lost to time, so they found a rock that looked like it could have been “Plymouth Rock” and moved it to the harbor under a classical canopy commemorating its importance (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1998a). Tourists wishing to see the Alamo between 1960 and 2010 might have stopped at the original in downtown San Antonio, Texas, or they may have preferred the reproduction, built in Brackettville, Texas, as the set for a John Wayne movie about the Alamo and maintained as a tourist site for the next five decades (Huxtable Reference Huxtable1997). Sam Houston’s Greek revival home in Texas has been transformed by subsequent generations into a “rough-hewn log cabin which Houston himself would have disdained,” but which tourists deem more consistent with their mind’s-eye vision of Houston’s home (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1998a). Hannibal, Missouri, has state historical markers commemorating not only spots where the real Mark Twain lived, but also locations where the fake characters from his books supposedly had their adventures (Daly Reference Daly2010). Similar “landmarks” exist in Romeo and Juliet’s Verona (Telegraph 2012). Tour guides in the Old City of Jerusalem take nuns on a Via Dolorosa that isn’t Christ’s path on the way to the crucifixion, but is rather a “more interesting” (and maybe more appealing?) path to follow (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1998a). Colonial Williamsburg for decades had no references whatsoever to slavery, and its outhouses used to be freshly painted in bright colors – historically inaccurate, for sure, but far easier on the eyes (Barthel Reference Barthel1990; Handler and Gable Reference Handler and Gable1997).

Amidst these unreliable narratives, shifting standards of what ought to be preserved prevail. Most of the older European societies whose edifices current generations are now spending enormous resources to preserve cared little for ancient structures, and some of them wouldn’t have given much thought to the idea that the past and present were meaningfully different. In the 1500s, St. Peter’s Basilica was razed and then rebuilt, a development that was (as best we can tell) uncontroversial, even for a building of such historic importance (Lowenthal Reference Lowenthal1998b). And with so many readers having walked through the current version, do we have grounds to complain?

The question of which golden era to commemorate is one that arises across cultures. Americans’ nostalgic sense of New England’s small towns is more an artifact of the nineteenth century than the seventeenth. After the Civil War, a pure, agrarian, and communitarian New England helped show that the prevailing side in the conflict was always destined to emerge victorious. And later in the nineteenth century, as immigration threatened colonial revivalists’ understanding of the American identity, the “fictions of New England resisted fact in order to stabilize the socially uncertain present” (Wortham-Galvin Reference Wortham-Galvin2010). The fact that the landscape of nineteenth-century New England did not match the vision that revivalists wanted to encounter meant that New England’s landscape needed to be remade. And similar questions about which “golden era” should be preserved play out in historic preservation debates in Europe. As Lowenthal explains:

Consider Rouen Cathedral, whose sixteenth-century timber spire gave way in 1822 to a cast-iron replacement unable to bear its own weight. A new spire is now needed. Should it honour the original or the historical continuity embodied in the fraud of a nonweightbearing load?