Introduction

The concept of compassion fatigue is explained as the emotional impact of the trauma indirectly while helping people who experience traumatic stress directly (Cavanagh et al. Reference Cavanagh, Cockett and Heinrich2020; Nimmo and Innzna Huggard Reference Nimmo and Innzna Huggard2013). At the same time, compassion fatigue is the negative effect of helping people who have experienced a traumatic event or who are suffering from pain (Şirin and Yurttaş Reference Şirin and Yurttaş2015). Compassion fatigue is the progressive and cumulative result of prolonged, sustained, and intense contact with patients, self-exploitation, and exposure to multidimensional stressors that lead to a compassion disorder that exceeds the nurse’s stamina levels (Gerard Reference Gerard2017; Sinclair et al. Reference Sinclair, Raffin-Bouchal and Venturato2017; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhang and Han2018).

Due to their profession, nurses are individuals who provide support, encouragement, and compassionate care for individuals who are faced with physical, emotional, and spiritual distress in the society (Karabey Reference Karabey, Özveren and Gülnar2021). With this, nurses are at risk of developing compassion fatigue because they are constantly exposed to the stress and traumatic experiences inherent in the profession and make self-sacrifice in different dimensions while providing care (Harris and Griffin Reference Harris and Griffin2015; Wentzel and Brysiewicz Reference Wentzel and Brysiewicz2018). Nursing is a care profession that includes cooperation, compassion, and universal values. Therefore, interpersonal communication skills and empathetic approach are the basic structures of nursing roles (Nibbelink and Brewer Reference Nibbelink and Brewer2018; Tsai Reference Tsai2020). However, nurses’ wrong approach to empathy and their willingness to help more can cause stress. When stress at work is unmanageable, the response may be chronic, work-related emotional stress (Yılmaz and Üstün Reference Yılmaz and Üstün2018). Sabo (Reference Sabo2011) saw empathy as a double-edged sword for healthcare professionals and suggested that empathy skills be used appropriately within professional boundaries. Compassion fatigue not only has a negative impact on nurses’ well-being, job satisfaction, and willingness to remain in the profession, but also negatively affects patient outcomes and satisfaction with healthcare services (Cimiotti et al. Reference Cimiotti, Aiken and Sloane2012; Ko and Kiser-Larson Reference Ko and Kiser-Larson2016; Rudman and Gustavsson Reference Rudman and Gustavsson2011). When the literature is examined, Jarrad and Hammad (Reference Jarrad and Hammad2020) found that nurses have extremely high compassion fatigue in their study on oncology nurses. Again, Balinbin et al. (Reference Balinbin, Balatbat and Balayan2020) in their study to determine compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among general medical-surgery nurses found that high monthly income positively affected compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue in nursing students is a condition that negatively affects students’ educational processes and social life (Michalec et al. Reference Michalec, Diefenbeck and Mahoney2013). Nursing students often encounter real-life trauma situations during their clinical experience, and similar workplace environment and climate as professional nurses (Michalec et al. Reference Michalec, Diefenbeck and Mahoney2013). Nursing students are practically acquainted with the realities of nursing during clinical training. They learn to care for acutely ill patients. In this learning process, they often face high-intensity workload and stressful learning environments, in situations where there is a shortage of personnel and resources, fear of making mistakes (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Boxer and Sanber2008; Reeve et al. Reference Reeve, Shumaker and Yearwood2013; Yıldırım et al. Reference Yıldırım, Karaca and Cangur2017; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Cai and Wang2015). Resilience is a complex construct that is not universally defined, but reflects the ability of a person, community, or system to adapt positively to challenges in a way that fosters growth and well-being. Resilience includes the capacity to “maintain its core purpose and integrity in the face of dramatically changing conditions” (Southwick et al. Reference Southwick, Bonanno and Masten2014; Zolli and Healy Reference Zolli and Healy2012). It is reported that the nursing education process globally is stressful for students (Chernomas and Shapiro Reference Chernomas and Shapiro2013; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Burnard and Bennett2010; Oner Altiok and Üstün Reference Oner Altiok and Üstün2013). Nursing students will graduate to areas of stressful practice, and resilience is an essential skill acquired for workplace survival. Nursing students also face stressors from academic workloads and deadlines (Tung et al. Reference Tung, Lo and Ho2018; Walker and Mann Reference Walker and Mann2016). In the United States, attrition rates for undergraduate nursing students vary widely, from 3% to 30% (Doggrell and Schaffer Reference Doggrell and Schaffer2016). A call to action from the American Association of Nursing Colleges (AACN) encourages schools to promote and create a culture of wellness as part of curriculum and organization. This includes evidence-based interventions to develop resilience and well-being skills. (AACN 2020). Endurance is recommended as an important weapon in the arsenal against compassion fatigue (Rees et al. Reference Rees, Breen and Cusack2015).

Psychological resilience generally refers to a process of success or adaptation (Hunter Reference Hunter2001; Peng et al. Reference Peng, Zuo and Miao2014). On the other hand, psychological resilience is defined as one’s ability to recover from difficult life experiences or the ability to successfully overcome change or disasters (Clauss-Ehlers Reference Clauss-Ehlers2008). Psychological resilience is a phenomenon that is perceived, recognized, learned, and involves a developmental process in the face of the realities we face (Basım and Çetin Reference Basim and Cetin2011). It is stated that individuals with high psychological resilience cope more successfully with stressful life events, have effective problem-solving and communication skills, and benefit more from social support during coping (Çapan and Arıcıoğlu Reference Çapan and Arıcıoğlu2014; Wilks and Spivey Reference Wilks and Spivey2010). Psychological resilience makes it easier for nurses to adapt positively to stressful working conditions and emotional distress caused by stressors (McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Jackson and Wilkes2012). It has been postulated that psychological resilience might play an important role in allowing nursing students to overcome challenges (Sigalit et al. Reference Sigalit, Sivia and Michal2016). When the literature is examined in their study to determine the post-traumatic development, emotional intelligence, and psychological resilience of nursing students, Li et al. (Reference Li, Cao and Cao2015) reported that psychological resilience in nursing students could help nursing students cope with difficulties in their future clinical work. Onan and Karaca Barlas (2018) conducted a study to evaluate the coping with stress course in terms of psychological resilience among a group of university nursing students and found that coping with stress caused a significant increase in self-perception and social resources, which are the sub-dimensions of psychological resilience. It is predicted that the level of compassion fatigue experienced by final nursing students, who are future professionals, can be reduced by increasing their psychological resilience. It is very important for nursing students to build, learn, and develop their psychological resilience, both for their own health and the health of the group they serve.

No study has been found on whether final year nursing students suffer from compassion fatigue and to what extent, and the effect of this situation on psychological resilience. The aim of this study is to determine the effect of compassion fatigue levels of nursing final year students on psychological resilience.

Research questions

1. What are the compassion fatigue levels of final nursing students?

2. What are the psychological resilience levels of final nursing students?

3. Is there a relationship between compassion fatigue and psychological resilience of final nursing students?

Methods

Participants and setting

The research was conducted in Turkey between November and December 2021 with 250 nursing students. Nursing students who accepted to participate in the study and filled out the forms formed the sample of the study. The purpose and nature of this study were explained to the participants, they were invited to participate in the research, and then the forms were applied. The data of the research were collected through social media.

Data collection

In collecting the research data, three forms were used: “Individual Information Form” created by the authors, “Compassion Fatigue Scale” to evaluate Compassion Fatigue, and “Psychological Resilience Scale” to evaluate the psychological resilience of nursing students.

Individual information form

In this form created by the researchers, there are four closed-ended questions: age, gender, place of residence, and socio-economic level of nursing students (Michalec et al. Reference Michalec, Diefenbeck and Mahoney2013).

Compassion Fatigue Short Scale

The scale was developed by Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Boscarino and Figley2006). It consists of two dimensions: secondary trauma and occupational burnout. The scale scores between 1 and 10. Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted by Dinç and Ekinci (Reference Dinç and Ekinci2019). There is no cut-off point in the scale. As the scores of the scale increase, the defined compassion fatigue level also increases. The scale consists of two sub-dimensions and does not contain any reverse items. A minimum of 13 and a maximum of 130 points can be obtained from the scale. The Cronbach α coefficient of the scale was reported as 0.87, 0.74 for the secondary trauma sub-dimension, and 0.852 for the work burnout sub-dimension (Dinç and Ekinci Reference Dinç and Ekinci2019).

Psychological Resilience Scale for adults

The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale developed by Friborg et al. (Reference Friborg, Hjemdal and Rosenvinge2003) was conducted by Basim and Cetin (Reference Basim and Cetin2011). A 5-point Likert-style rating is made between the statements for which I found the scale solution and which I often cannot predict what to do. It has been reported that as the score obtained from the scale increases, psychological resilience also increases. The scale scores between 33 and 165 points. The scale consists of a single dimension and the total Cronbach Alpha coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.86 for both the student and employee samples. In this study, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient of the scale was found to be 0.84.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed with IBM SPSS V25 program. In the examination of socio-demographic data, frequency, and percentage were used. The conformity of the distribution of the data to the normal distribution was tested by examining the skewness and kurtosis values (+1, −1) with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test were used to compare non-normally distributed data. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between variables. The level of relationship between variables is weak if the correlation coefficient is between 0 and 0.29; medium if it is between 0.30 and 0.64; strong if it is between 0.65 and 0.84; if it is between 0.85 and 1, it is interpreted as very strong (Ural and Kılıç Reference Ural and Kılıç2011). The level of significance was taken as p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethics committee approval (2021-24/11) and institutional permission were obtained before the study was conducted. Nursing students who agreed to participate in the study were informed about the purpose and process of the study, and their written consents were obtained. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

When the distribution of nursing students participating in the study according to some introductory characteristics was examined, it was determined that 65.20% of the sample was 7 female and 70.80% was between the ages of 20 and 23. It was determined that 57.60% of the nursing students lived in dormitories and 58.40% of them had a medium socio-economic income (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of individuals by some descriptive characteristics

Compassion Fatigue Scale total score average of the nursing students participating in the study was found to be 80.58 ± 18.82, the occupational burnout sub-dimension score average of the scale was 50.36 ± 12.12 and the secondary trauma sub-dimension score average was 30.22 ± 8.99. The students’ Psychological Resilience Scale mean score was calculated as 94.73 ± 11.18 (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean scores of the Compassion Fatigue Scale and Resilience Scale

When the Compassion Fatigue Scale and the subscale mean scores and some descriptive features were compared, the mean score of the students with high socio-economic status was found to be 69.72 ± 14.04 (p = 0.002) and the mean score of the occupational burnout sub-dimension score of 41.88 ± 9.68 (p = 0.005) (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean scores of the Compassion Fatigue Scale and Resilience Scale according to sociodemographic characteristics

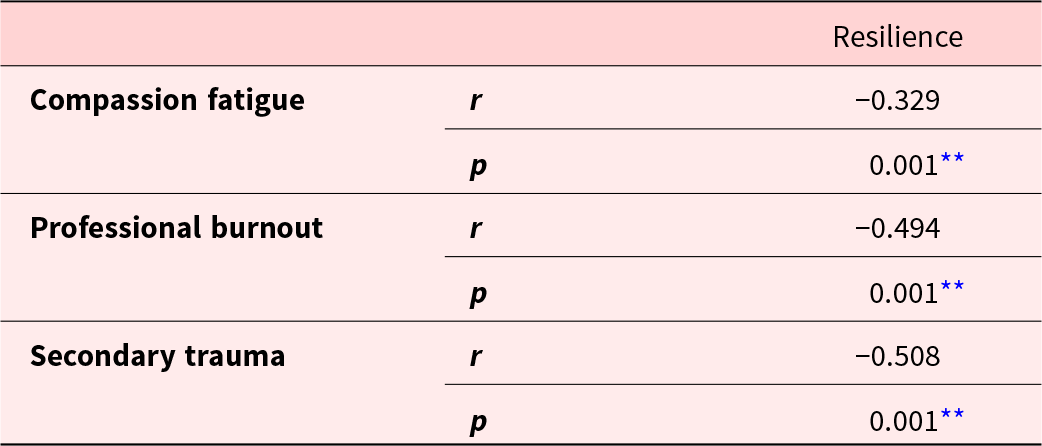

The relationship between Compassion Fatigue and Psychological Resilience scales is shown in Table 4. Accordingly, there is a moderately negative and significant relationship between Compassion Fatigue Scale and all its sub-dimensions (occupational burnout, secondary trauma) and Psychological Resilience Scale (p = 0.001).

Table 4. The relationship between compassion fatigue and resilience

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Discussion

In our study to determine the effects of nursing final year students’ compassion fatigue levels on students’ resilience levels, it was concluded that final year nursing students’ compassion fatigue levels significantly affected resilience, and in this context, our findings were discussed in relation to the relevant literature.

While patient care and interactions are at the core of healthcare, they are also a major source of stress for many service providers (Kelly and Adams Reference Kelly and Adams2018; Sorenson et al. Reference Sorenson, Bolick and Wright2017). Stewart (Reference Stewart2009) also found that compassion fatigue negatively affects nurses’ well-being, job satisfaction, and willingness to stay in the profession. When the literature is examined, it has been reported that young caregivers with limited experience and poor coping strategies are at higher risk for developing compassion fatigue (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, Girdler and McDonald2013; Sorenson et al. Reference Sorenson, Bolick and Wright2017). When the literature is examined, it has been determined that all factors such as the inability of the person to work on his feelings about a traumatic event or to provide care to traumatized individuals, to determine effective coping mechanisms, and to develop emotional intelligence through education or experience, all contribute to the development of compassion fatigue (McGarry et al. Reference McGarry, Girdler and McDonald2013; McKenna and Rolls Reference McKenna and Rolls2011; Mizuno et al. Reference Mizuno, Kinefuchi and Kimura2013). Again in the literature, it has been determined that the lack of knowledge in the working environment is a cause of anxiety fatigue in nurses (Adimando Reference Adimando2018; Drury et al. Reference Drury, Craigie and Francis2014).

In our study, compassion fatigue levels of final year nursing students were found to be moderate (Table 2). When the literature is examined, Babaei and Haratian (Reference Babaei and Haratian2020) reported that nurses have moderate compassion fatigue in their study on cardiovascular nurses. Again, Ruiz‐ Fernández et al. (Reference Ruiz‐ Fernández, Ramos‐ Pichardo and Ibáñez‐ Masero2020) reported in their study that professionals working in COVID-19 units and emergency services experience higher rates of compassion fatigue. When the literature on nursing students is examined, most of the previous studies for clinical trainee nursing students focused on stress (Admi et al. Reference Admi, Moshe-Eilon and Sharon2018), satisfaction with the clinical environment (Woo and Li Reference Woo and Li2020), and burnout syndrome (Valero-Chillerón et al. Reference Valero-Chillerón, González-Chordá and López-Peña2019). Studies on compassion fatigue in nursing students have been limited.

Resilience is a recommended way to combat negative effects on professional quality of life and traumatic experiences and to promote nursing student success (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Wu and Hung2019; Robertson et al. Reference Robertson, Cooper and Sarkar2015; Thomas and Asselin Reference Thomas and Asselin2018; Thomas and Revell Reference Thomas and Revell2016). In our study, it was found that the psychological resilience levels of final year nursing students were moderate (Table 2). When the literature is examined, Ríos-Risquez et al. (Reference Ríos-Risquez, García-Izquierdo and Sabuco-Tebar2016) and Smith and Yang (Reference Smith and Yang2017) found that the psychological resilience levels of nursing students are moderate in their nine studies. Maintaining a good level of psychological well-being is considered a vital component in the education and development of future nurses (Ratanasiripong and Wang Reference Ratanasiripong and Wang2011).

The economic situation is perceived as a power by individuals and this perceived power helps individuals to develop coping strategies (Mussi et al. Reference Mussi, Pires and Silva2020; Oliveira-Bosso et al. Reference Oliveira-Bosso, Marques-da Silva and Siqueira-Costa2017). In our study, it was determined that the final year nursing students with a high socio-economic level had lower Compassion Fatigue total score (p = 0.002) and Occupational Burnout Sub-dimension mean score compared with students with other socio-economic levels (p = 0.005) (Table 3). When the literature is examined, Manzano-García et al. (Reference Manzano-García, Montañés and Megías2017) reported that the burnout score averages of nursing students with low socio-economic level were higher than other groups.

Looking at the score range of the measurement tools used in our study, it was determined that the levels of compassion fatigue and psychological resilience of nursing final year students were moderate, and as the levels of compassion fatigue increased, psychological resilience decreased (Table 4) (p = 0.001). The stress that nursing students face in the field of practice and the compassion fatigue it brings with it can affect the academic attrition in nursing education (Pryjmachuk et al. Reference Pryjmachuk, Easton and Littlewood2009), student performance (Gibbons et al. Reference Gibbons, Dempster and Moutray2009; Grobecker Reference Grobecker2016), and coping ability (Goff Reference Goff2011). Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kim and Park2017) determined in their study that emotional intelligence, psychological well-being, and self-esteem are necessary for psychological resilience in nursing students. Again, Mangoulia et al. (Reference Mangoulia, Koukia and Alevizopoulos2015) reported that more education can help reduce prevalence rates of compassion fatigue and burnout, as increased knowledge is a potent protective agent.

There are gaps in understanding the complex relationships between factors that influence resilience and innate qualities, such as awareness and self-compassion. In addition to academic responsibilities, it is very important to investigate the relationship between nursing students’ resilience and compassion fatigue in practice areas. However, no study has been found in the literature that deals with the reflections of nurses’ compassion fatigue levels on psychological resilience. In this context, the discussion of our findings was carried out with limited and indirect resources, and our comments on our findings were kept in the foreground.

Limitations

Since the sample of this research consists of 250 nursing students studying in nursing departments in Turkey and who agreed to participate in the research, its generalizability to the population is limited. Descriptive and observational studies are needed to examine the compassion fatigue and psychological resilience levels of nursing students every year.

Conclusion

According to the results of our research, it was determined that the compassion fatigue levels of final nursing students with higher socioeconomic status were lower and that the compassion fatigue levels and psychological resilience of the final nursing students were moderate. Again, in the study, it was found that there was a negative and high level relationship between nursing students’ compassion fatigue levels and all its sub-dimensions and psychological resilience. Resilience can improve psychosocial functioning and professional performance, including for nursing students facing stressful clinical experiences. It is very important to determine the compassion fatigue and psychological resilience levels of nursing students, to determine the existing problems, and to take initiatives for this. In addition, it is thought that future nurses can make radical changes in their views and attitudes toward the patient, themselves, and the profession, which can lead to improvement in the performance of the nurse and her profession.

Suggestions

In order to increase the psychological resilience levels of nursing students, it is important to add content that will serve this purpose to the nursing curriculum. It is recommended that nurse academicians and clinicians recognize nursing students’ compassion fatigue and support them to increase psychological resilience.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the nursing students who participated in this study.

Author contributions

TK: design of the study and manuscript revision; TK: literature searching, assessing the quality of literature, statistical analysis, and writing; TK: assessing the quality of literature and methodological guidance

Fundıng

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.