And taking her stand by his bed, Judith said in her heart, ‘Adonai God of all power, look down with favor in this hour upon the works of my hand for the exaltation of Jerusalem; because now is the time to come to the aid of thine inheritance and to carry out my designs for the shattering of the enemies who have risen up against us.’ And going to the bedpost which was at Holofernes' head, she took down from it his sword, and nearing the bed, she seized hold of the hair of his head and said, ‘Give me strength this day, Adonai God of Israel.’ And with all her might she smote him twice in the neck and took his head from him.Footnote 1

With its intense drama, seduction and spectacular execution, the story of Judith's slaying of Holofernes was often represented during the baroque era. The original, anonymous account from the Apocrypha tells of a Jewish heroine who employs deceitfulness and flattery in order to kill her opponent, the despotic Assyrian general Holofernes. Aware of Holofernes's sexual infatuation with her, Judith entices him, watches him become inebriated and then beheads him as he falls into a fatal slumber. Judith goes on to free her people from the Assyrian invasion; for her great deed, she is for ever revered as God's agent and Israel's valiant heroine.Footnote 2 The complex nature of this particular heroine had fascinated the Western world long before the Baroque – and with good reason. Judith's multifaceted character verges on paradox and defies stereotypes. On the one hand, she is praised for her strength, beauty, resolution, assertiveness, eloquence with words, wisdom and acumen – even her enemies concede that ‘There is not such a woman from one end of the earth to the other, for fairness of face, and understanding of words.’Footnote 3 On the other hand, she is honoured for her chastity and virtue and for her humble fear of God (‘no one spoke ill of her, so devoutly did she fear God’).Footnote 4 Elena Ciletti and Henrike Lähnemann put it succinctly: ‘Humble and bold, pious and devious, widow and warrior, Judith is ever composed of contradictions barely contained in tense equilibrium.’Footnote 5 Judith's fundamental paradox extends to the realm of gender: her character exudes fascination precisely because her behaviour transcends gender boundaries. It has been argued that Judith's character represents the ‘archetypal androgyne’, one that can navigate effortlessly between feminine seductiveness, masculine heroism and asexual virtue.Footnote 6 Throughout Western history, the artistic reception of the Judith story has emphasized the heroine's conflicting traits. Indeed, Ciletti contends that ‘Judith would seem remarkable to us [today] if only for the sheer quantity of opposing identities and symbolic usages imposed on her across the centuries, from patriot to Virgin Mary prototype to femme fatale.’Footnote 7 Such multifaceted images are not simply a reflection of her many-sided character but also ‘participate in a complex, evolving intellectual history’ of the Judith theme, which, Ciletti points out, ‘defies definitive formulation’.Footnote 8

Baroque visual artists, poets and musicians capitalized on Judith's contradictions, often emphasizing the theatricality of her spectacular deed. Most readers will be acquainted with the story through two iconic baroque paintings, known for their persuasive force in representing the murder: Giuditta decapita Oloferne (Judith Decapitating Holofernes) (c1620) by Artemisia Gentileschi, housed in the Uffizi in Florence, and Giuditta che taglia la testa a Oloferne (Judith Beheading Holofernes) (c1599), by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, housed in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica (Palazzo Barberini) in Rome. Yet these images are just two from a baroque visual tradition that includes one hundred and eighty-seven works, twenty-eight of which treat the moment of decapitation itself.Footnote 9 In literature, Judith was used emblematically in the religious controversies between Protestants and Catholics that plagued France, England, Scotland and the Low Countries, causing much violence and bloodshed; by 1600, she would become a model of ‘rebellion, resistance, and assassination’ for Catholics and Protestants alike, occupying, according to Margarita Stocker, a ‘remarkable position within the propaganda of international conflict’.Footnote 10 In music, composers and librettists capitalized on the contrasts inherent in the story. Oratorio settings often emphasize conflicting themes such as day versus night, masculine desire versus feminine beauty, combative spirit versus intimate seduction; and they sometimes highlight the struggle between the two opposing groups of the military conflict, the Assyrians and the Bethulians, in order to serve specific political agendas.Footnote 11

In the oratorio such contrasts were articulated primarily through character depiction and conflict. In the cantata, it was a different matter. Its fundamentally epic nature reduced the possibility of direct character intervention, thereby limiting the potential for staging contrast. Because the great majority of baroque cantatas are designed for one voice, the singer-narrator alone controls the characters' interventions, allowing them free rein only within his own imagined experience of the action. Thus in cantata texts, characters rarely speak directly and, even when they do, it is the narrator that articulates their identities through his own voice.Footnote 12 These features of the genre may explain why composers preferred to rely on the more dramatic framework of the oratorio to articulate contrast. Sheer numbers are significant: compared with the several hundred oratorio librettos devoted to the Judith story, there are only three known baroque cantatas on the subject.Footnote 13 Yet precisely because of its limitations and idiosyncrasies, the cantata may well constitute the more revealing genre for exploring the musical strategies composers could employ to give agency to Judith and the multifarious aspects of her character. This article focuses on two French cantatas composed by Sébastien de Brossard (1655–1730) and Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665–1729), both based on the same text by librettist Antoine Houdar de La Motte, which have not received the attention they deserve.Footnote 14 Because both are based on the same text and because both were conceived by French composers at about the same time (1708)Footnote 15 – thus eliminating potential geographical and chronological variables of style – these cantatas offer a compelling case study, shedding light on fundamental issues of text-setting. The comparison will show how individual and forward-looking Jacquet de La Guerre's setting is compared to Brossard's normative approach to the text, and will complicate commonly held notions concerning the centrality of the text in the French Baroque.

Such notions were ingrained in the French baroque collective imagination, owing to the difficulty most Frenchmen had in accepting opera (aptly termed tragédie en musique) as anything other than a fundamentally literary genre in which music plays a subservient role; this difficulty in accepting opera is well demonstrated by the paradoxical solution of conceiving it and justifying it primarily as an inversion of spoken tragedy, as its negative, so to speak.Footnote 16 In the cantata, the anxiety concerning the balancing of text and music took the more moderate form of a typical early eighteenth-century issue – the joining of Italian music to French words within the context of the so-called réunion des goûts, as evident in several composers' prefaces to cantata books; yet scholars point out that the cantata also enjoyed the status of minor literary genre.Footnote 17 This context makes Jacquet de La Guerre's music all the more unusual, particularly in her choice of instrumental accompaniments and instrumental symphonies, which betray a strong narrative impulse to bypass La Motte's text at key moments of the story. Such moments create what could be called musical ekphrases. These are narrative images that emanate from the text yet add a parallel dimension to it by filtering the action through the composer's perspective, and by stretching specific moments beyond their strictly necessary narrative purpose, in order to afford Judith the appropriate depth and complexity of character denied by La Motte. Jacquet de La Guerre's choice of and confidence in instrumental music to affect narrative time and achieve a narrative perspective vis-à-vis the text is unique in that it goes beyond the conventional wisdom of her own country, whose notoriously sceptical attitude towards instrumental music on account of its inability to convey meaning was famously encapsulated by Fontenelle's ‘Sonate, que me veux-tu?’.Footnote 18

Recent research has shed light on Jacquet de La Guerre's compositional style as well as on her unusual position as one of the first women to achieve professional status as a composer in France, and Mary Cyr in particular has illuminated the special qualities of her cantatas.Footnote 19 The present study expands on current scholarship and continues the quest to define the composer's distinctive style. Jacquet de La Guerre's confidence in music's potential for signification outdoes not only the typical procedures of the French baroque cantata, but also those of the Italian cantata. That cantata composers made up for the lack of character presence through particular musical techniques is not a new notion. Hendrik Schulze has recently shown how Legrenzi uses various techniques to achieve the ‘staging’ or ‘embodiment’ of a character, and these include changes in metre from duple to triple, changes in melodic style from syllabic to lyrical, unexpected harmonic progressions to signal shifts of character, and imitative entries between continuo and voice to suggest dialogue or anticipate the final punchline from the narrator.Footnote 20 Margaret Murata discusses similar narrative shifts in the musical articulation of the singing self in the Italian cantata of the seventeenth century through changes in musical style and the dissolution of the recitative–aria paradigm into a loose succession of formally nebulous sections.Footnote 21 Elsewhere I have discussed the dramatic uses of instrumental music in the French baroque cantata to stage similar shifts in singer subjectivity, and to stage instruments as dramatic ‘characters’ functioning as interlocutors for the singer.Footnote 22 Yet such examples constitute the composers' overt articulations or expansions of the latent dramatic potential of the text. Although emanating from the text, Jacquet de La Guerre's singular use of instrumental music, as we shall see, represents a covert expression of her own perspective around the poet's, one that aims to complicate the Judith character and augment her dramatic import in the story. La Guerre's original treatment of Judith is typical of a tendency in her sacred cantatas, many of which feature original musical treatments of Biblical heroines, and even in her operatic music, which also features remarkable psychological depictions of female characters.Footnote 23 Her interest in femmes fortes also reflects a larger trend in French literary and artistic practice, of which Judith provides an emblem. Arguably, her unique status as a successful woman composer may have given her a particular viewpoint on the Judith story, yet it should be said outright that the originality of her music transcends issues of gender, much as Judith's enigmatic figure transcends roles.

Focalization

To illustrate Brossard's and Jacquet de La Guerre's fundamentally different ways of treating Judith and her story, I will employ the concept of focalization – the term used in literary and film theory to mean point of view or filtered perspective – as a theoretical framework, one that has rarely been applied to music thus far, despite the musicological interest of the last two decades in music's narrative potential.Footnote 24 For the present purpose the well-known baroque visual interpretations of Judith's slaying of Holofernes by Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi and their strikingly different use of the maidservant as filter will provide a valuable means of introducing focalization before reviewing its application to music. My aim in discussing these two paintings is primarily methodological, to show that the role of the maidservant and her relation to Judith can be employed as a useful tool for understanding the differing perspectives of the two composers, on the one hand, and the rapport between the narrator and Judith in La Motte's text, on the other.Footnote 25 The following discussion does not attempt to set up a clear-cut gender equation, as has been attempted between Jacquet de La Guerre's cantata and Gentileschi's painting.Footnote 26 Rather, aside from Jacquet de La Guerre's depiction of Judith with the dignity and heroism denied to her by La Motte, which does recall Gentileschi, the resulting analysis complicates the issue of gender by showing that Brossard and Gentileschi are actually closer in formal conception concerning the murder's purpose, while Jacquet de La Guerre's perspective filtering recalls Caravaggio's use of the maidservant, which complicates the scenario. I also aim to reconsider the figure of the maidservant and her dramatic significance as a filter. While art historians have noted Gentileschi's innovation of the young and vigorous maidservant as active partner compared with Caravaggio's more traditional representation of the old crone acting as a foil to Judith, scholars have been surprisingly reticent about the narrative role of the maidservant in Caravaggio's painting.Footnote 27 With few exceptions, Caravaggio scholars have been more concerned to ascribe the contrast between the youthful Judith and the old maidservant to Caravaggio's awareness and manifestation of the Renaissance notion of contrapposto, and to trace the old crone type to sixteenth-century traditions of painting, theatre and caricature prints than to engage with the narrative stance of the figure per se and the role she plays within (and without) the painting.Footnote 28

Deliberately disregarding the story from the Apocrypha, in which the maidservant waits outside the tent and prays while the deed is performed,Footnote 29 both artists choose precisely to mediate the action through her perspective, yet they do so in radically different ways. While Gentileschi takes a direct, blunt approach to representing the murder, Caravaggio complicates the action by means of stark contrasts between opposing psychological types. In both paintings the maidservant plays a significant role in establishing the scene. In Gentileschi's Judith Decapitating Holofernes (Figure 1) the assisting presence of the maidservant enhances Judith's powerful might as she performs the deed.Footnote 30 The painting represents a perfectly efficient example of teamwork, one in which, Mieke Bal argues, ‘the arms express strength and determination, the faces commitment to the task at hand’.Footnote 31 Bal notes that ‘Gentileschi's work radiates a contained and serious, almost organized passion that enhances the sense of efficacy of the work being done.’Footnote 32 Not so in Caravaggio's treatment of the same story (Figure 2).Footnote 33 There, in place of a determined female warrior we find a perplexed, diaphanous and mannequin-like Judith, whose youthful beauty contrasts with both the beastly agonizing cry of Holofernes and the viciousness of the old maidservant. Unlike Gentileschi, who chooses to impart a business-like, concentrated intensity to her female figures, Caravaggio distributes the intensity of the moment among the trio of figures and their wildly different psychological reactions to the murder, thus complicating the meaning of the action for the viewer.

Figure 1 Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c1654), Giuditta decapita Oloferne (c1620). Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

Figure 2 Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), Giuditta che taglia la testa a Oloferne (c1599). Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica.

In Gentileschi the maidservant is thus not only an active follower but also a partner in crime, Judith's Doppelgänger, as Nanette Salomon puts it. This is highlighted by her position at the apex of the painting, by her active holding of Holofernes and by her close proximity to Judith, as if to create one single powerful instrument of war against the tyrant.Footnote 34 She contributes to what feels like a turbulent yet dignified harmony of action efficiently aimed at one goal – Holofernes's death. Indeed, the strong ‘feeling of joint psychic involvement’ of the two women, who seem ‘united in action and mind’, as Bissell puts it, has persuaded several art historians to perceive a strong sense of womanly ‘sisterhood’ emphasizing feminine ‘strength of body and spirit’ against a male oppressor.Footnote 35

Caravaggio situates the maidservant to the side of action instead, thus deliberately accentuating her narrative distance. Unlike Gentileschi's maidservant, Caravaggio's takes part in the action not so much as character – at least not yet, since she is eagerly waiting to place Holofernes's head in her sack – but rather as emotional witness. Her disturbingly voyeuristic posture, lurking on the edge of the painting, gives her a privileged, omniscient position that bridges the gap between the observer and the artwork. Operating within the painting, she silently goads a seemingly perplexed Judith; operating as a link between the painting and its beholder, she draws the beholder into the drama by witnessing and savouring the murder for him, exhibiting the very emotional traits Judith lacks – anticipation and a desire to kill. It is her gaze that connotes her privileged narrative distance. Unlike the stare of the main protagonists – Judith looks unemotionally focused, physically present yet absent in spirit, Holofernes desperately pleads to the beholder for empathy – the maidservant appears entranced. Yet her transfixed gaze lacks a clear point of reference and looks beyond the visible, as it were, as if she alone held the key to understanding the true significance of the action. Whereas Gentileschi's maidservant is too caught up in the act itself, dutifully performing as if wearing blinders, Caravaggio's maidservant possesses the benefit of the critical point of view: the action is thus focalized through her eyes. She epitomizes what Italian Renaissance art theorist Leon Battista Alberti suggests in his treatise On Painting (first appearing in 1435) as a way to strengthen the proper representation of the istoria – the use of a ‘commentator’ figure inside the painting:

In an istoria I like to see someone who admonishes and points out to us what is happening there; or beckons with his hand to see; or menaces with an angry face and with flashing eyes, so that no one should come near; or shows some danger or marvelous thing there; or invites us to weep or to laugh together with them. Thus whatever the painted persons do among themselves or with the beholder, all is pointed toward ornamenting or teaching the istoria.Footnote 36

In Alberti's description the figure inside the painting clearly establishes a powerful ‘emotional link’ between the painting and its beholder.Footnote 37 This notion recalls twentieth-century narratological theories of focalization, according to which Caravaggio's maidservant would function as a focalizer, a character whose point of view orients the beholder's perception of the action. Manfred Jahn has aptly defined focalization as ‘the perspectival restriction and orientation of narrative information relative to somebody's (usually a character's) perception, imagination, knowledge or point of view’.Footnote 38 The concept of focalization owes much to the seminal work of Gérard Genette, who distinguishes between the categories of perspective and narrative agent in literary texts by employing two fundamental questions, ‘who sees?’ or ‘who perceives?’ (the focalizer) and ‘who speaks?’ (the narrator).Footnote 39 In literary texts, focalization can be viewed as ‘a relation between the narrator's report and the characters' thoughts’.Footnote 40 In other words, it is defined by the constantly shifting amounts and kinds of narrative information imparted by the narrator or by a reflective character inside the story in order to orient the reader's perception of the scenario. If the narrator's knowledge or point of view overshadows that of the character, we are dealing with external focalization; conversely, internal focalization occurs whenever the knowledge or perspective of a reflector-character inside the story overshadows that of the narrator.Footnote 41

Although originally conceived for literary texts, this model offers a useful framework for understanding the rapport between the two agents at work in a hybrid genre like the cantata: the narrating voice and the composer. In The Composer's Voice Edward T. Cone subsumes the narrator's voice within the all-inclusive persona of the composer, who ostensibly ‘appropriates’ the text and ‘makes it his own by turning it into music’.Footnote 42 I would like to reframe the issue in terms of a dynamic rapport between two parallel yet constantly shifting perspectives, converging and diverging in a competition to guide the listener's perception. This is more in keeping with reception by listeners of the time, who according to Jean Bachelier varied between ‘those who clung to the words’ and those who ‘were struck by the music’.Footnote 43 The rapport between the narrator and the composer can thus be conceived in terms of the shifting quantity and type of information, knowledge or point of view each agent chooses to convey to the listener. Although both agents are external focalizers (they are external to the fictional world), their perspectives act as a connecting bridge between the audience and the narrative world, opening up glimpses of it for the listener. A composer's view can converge with or diverge from the text: the composer can blend in with the poet, yielding to his perspective, as it were, or choose to augment the emotional import of a particular character, aspect, mood or moment in the story in a way that might diverge from the narrator's view. As we shall see, Brossard's setting is devoid of additional emotive information: his point of view matches, for the most part, that of the textual narrator, and his subsidiary role recalls the dutifulness of Gentileschi's maidservant in helping Judith to accomplish her deed. Conversely, Jacquet de La Guerre chooses to augment and complicate the text with emotive information that makes it tridimensional, thereby focalizing the action through her own perspective. Her point of view overshadows the narrator's in specific moments of the narrative, and her focalizing role recalls the critical stance of Caravaggio's maidservant in presiding over the action. Her music bypasses the text, not so much in meaning, but as the primary means through which the listener is catapulted into the fictional world. This accords with Manfred Jahn's understanding of focalization as ‘a means of opening an imaginary “window” onto the narrative world, enabling the reader to see events … through the perceptual screen provided by a focalizer functioning as a story-external or story-internal medium’.Footnote 44 The intense brevity of Jacquet de la Guerre's musical ekphrases also squares with what Genette argues concerning focalization – that its types and patterns do not ‘always bear on an entire work, but rather on a definite narrative section, which can be very short’.Footnote 45

La Motte and His Narrator(s)

Let us return to Caravaggio's maidservant and her double stance – as a goading figure to Judith, on the one hand, and as a character looking into the painting and orienting the vision of the beholder, on the other. Her relationship to Judith recalls the rapport between the narrator and Judith in La Motte's text. Much like Caravaggio's Judith, whose youthful inexperience and finicky perplexity benefit from the intense and decisive presence of the maidservant, La Motte's Judith likewise needs the authoritative presence of the narrator in order to complete her task. Indeed, in the central section of the cantata (see Table 1) the narrator constantly guides – and often goads – what he presents as a wavering Judith. This can be noted, for example, in his description of her vacillation immediately before the deed (see number 6 in Table 1) – her arm remains suspended as if to underscore her indecision, yet she trembles with vengeance – and in his plea for Heaven's help to assist her ‘distraught heart’. Moreover, at the end of the poem, the narrator reminds the audience of Judith's weakness by noting that even ‘the weakest hand is sufficient for His [God's] miracles’ (final aria in Table 1), an image that recalls the puppet-like Judith of Caravaggio. Unlike Holofernes, who is allowed to voice his desire in the first aria, Judith is never allowed to speak in the first person. Instead, employing exhortatory language that sounds at times vaguely patronizing, the narrator constantly addresses Judith directly and tells her what to do: to ensnare Holofernes with her looks (‘jettez sur luy les regards les plus doux’), to hasten his drunkenness (‘hâtez, hâtez, l'yvresse’; number 3 in Table 1) and to arm herself and get ready for the deed (‘Armez-vous, armez-vous, et d'un bras magnanime’; number 5 in Table 1). Moreover, he exhorts her twice to execute Holofernes, literally (‘enfoncez le trait qui le blesse’; number 3) and symbolically (‘éteignez dans son sang l'amour qui l'a séduit’; number 5). La Motte's narrator thus addresses the heroine through the apostrophe, a rhetorical figure that, as Elizabeth Block has shown in the context of Homeric narrative, allows the narrator to guide the listener's response by ‘verbalizing emotion toward either a real or [an] imagined object’.Footnote 46 Block notes that in apostrophes,

The speaker pretends to feel, for example, anger, fear, or sympathy, in order that through himself his audience may confront, in the particular context, these same emotions. Apostrophe … thus asks the audience to respond, ideally, as the narrator responds to the situations or evaluations that he introduces.Footnote 47

Table 1 Text from La Motte, Judith

By apostrophizing Judith rather than having her speak directly, La Motte's narrator saps the power of the heroine's voice, thus shifting the focus of the attention away from Judith in favour of his own emotional rapport with the reader. He thus focalizes the scenario through his own eyes, bridging the narrative gap between himself and the audience while restraining Judith and setting her aside.

This recalls some of La Motte's most common habits of narrative control employed in his controversial critique of Homer's Iliad, his Discours d'Homère, published conjointly with his own twelve-book ‘imitation’ of the Iliad in 1714. Although the book's publication boosted La Motte's celebrity and reputation, it also ‘set off an eruption of hostility’ among literary circles in early eighteenth-century France, which must be understood within the context of the ongoing quarrel between the ancients and the moderns (La Motte was a staunch supporter of the latter).Footnote 48 In his version of the Iliad, La Motte turns several speeches from first to third person, thereby robbing the original characters of their own voices. This occurs in Book 22, immediately prior to Hector's death at the hands of Achilles – in which La Motte turns ‘Hector's “agitated” soliloquy, through which Homer shows the beginning of his self-doubt … from direct speech to third-person narrative, as the poet tells us what Hector thinks’ – thereby mitigating Hector's original ‘urgency and the pity of [his] melancholy fantasy’.Footnote 49 Similarly to the way he addresses Judith in his cantata, La Motte also uses apostrophe in his version of the Iliad to inflate his authorial voice. For example, in the judgment of Paris, one of the episodes depicted in the ekphrasis of Achilles's shield, La Motte describes ‘the process by which Paris's hopes turn fatal’ through an apostrophe to Paris in the narrator's voice – ‘Tu te repais, Pâris, d'un bonheur adultère … Sçais-tu juge imprudent ce qu'il doit te coûter?’ (You feed yourself, Paris, on an adulterous happiness … Do you know, imprudent judge, what it must cost you?).Footnote 50

La Motte's manipulation of the speeches from first to third person can be understood not only as a way of exercising authorial power, but also as a way of sanitizing Homer's text, removing what he perceived as textual excesses that would not suit the sensibility of his contemporary French audiences. Homer's narration does not follow what La Motte christened the unity of interest, or ‘the principle that must guide a poet in his choice of circumstances’,

l'unité qui doit régner dans le tout doit aussi régner dans chaque partie: c'est-à-dire que, comme l'assemblage des faits qui composent tout le poème ne doit produire qu'un effet unique et général, l'assemblage des circonstances qui composent chaque fait particulier ne doit produire aussi qu'un effet unique, quoique subordonné à l'effet général.Footnote 51

the unity that must govern the whole [which] must also govern each part: in other words, just as the assemblage of the facts that make up the poem must produce only an effect both singular and general, so must the assemblage of the circumstances that make up each particular fact produce only a singular effect, even though subordinate to the general effect.

To achieve this end, La Motte tells us that he has ‘tried to render the narration more rapid than it is in Homer, the descriptions grander and less charged with minutiae, similes more exact and less frequent’.Footnote 52 La Motte excises lengthy descriptive passages that hold up the action, sanitizes much of Homer's gory language and avoids long lists and detailed inventories, deeming them ‘cold and languishing’ and inappropriate for his contemporary audiences.Footnote 53 For the same reason, he rewrites and reduces Homer's notoriously lengthy ekphrasis, such as the episode of Achilles's shield, omitting all pictorial references to sound and motion.Footnote 54 He also removes all poetic repetitions – ‘boring refrains’ and ‘epithets already repeated a thousand times’, as he himself puts it – and he omits any narrative foreshadowing, such as dreams or prophecies (prolepses in Genette's jargon), so as to maintain suspense and not spoil the effect of ‘surprise’.Footnote 55

The Composers and Their Perspectives

The radically different musical responses to La Motte's text by Sébastien de Brossard and Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre reflect their differing degrees of narrative involvement in the story, recalling the strikingly different stance of the maidservants in Caravaggio and Gentileschi. Brossard follows La Motte's plan by animating the narrator without regard for Judith, with well-crafted yet unremarkable recitatives, while ensuring continuity through key, use of run-on movements and avoidance of da capos, and by rearranging the text at the end of the piece for the sake of unity of action. His concern for connecting the events together upholds – even intensifies, as is demonstrated by his rearrangement of the text at the end – La Motte's strong belief in the principle of the unity of interest, and his subsidiary role in and allegiance to La Motte's vision recalls the allegiance of Gentileschi's maidservant – ready to act and follow on command for a good cause. Conversely, Jacquet de La Guerre lingers on and stretches specific narrative moments that forgo La Motte's typical concern for unity in favour of depicting Judith's complex character. Her music affects narrative time by slowing down the action and focusing on important dramatic moments, forcing the listener to pay heed much as the transfixed gaze of Caravaggio's maidservant captures the beholder's attention.

Their musical responses to La Motte's text differ in several respects, both at the formal level and at the local level of musical rhetoric. At the formal level, Brossard's dramatically efficient structure recalls the efficiency of Judith and her maidservant in Gentileschi's painting. Table 2a shows Brossard's linear trajectory, which employs parallel keys – C minor to C major – to emphasize the path from tragedy to triumph, a strategy for which there is a precedent in Charpentier's oratorio Judith sive Bethulia liberata, which moves in similar fashion from A minor to A major.Footnote 56 Brossard's concern for emphasizing both the celerity of the action and its ultimate end goal – triumph – can be observed through his treatment of the last four movements as run-ons (represented as horizontal arrows in Table 2a). His emphasis on action with a purpose at the expense of character depiction means he does not dwell on the murder as a tragic event; rather, he underscores it as a necessary evil, as a civic and moral duty in order to achieve the final objective, as it were.Footnote 57 This approach squares with the composer's own aesthetic vision of the cantata as a useful tool for inculcating morals:

il est seur, qu'en choisissant des sujets, ou pieux, ou du moins qui n'ayent rien de contraire aux bonnes mœurs on y peut tellement joindre l'utile à l'agréable que les plus sévères seront obligez d'avoüer qu'elles ne sont pas moins instructives que divertissantes, et qu'on pourroit par leur moyen renouveler en nos jours, cette manière d'instruire si usitée (commune) chez les anciens …Footnote 58

Table 2a Brossard, Judith ou la mort d'Holoferne (between 1703 and 1708)

it is certain that if the subjects are selected with care, whether sacred, or at least containing nothing contrary to upright behaviour, then may the useful be combined with the agreeable so that the severest critics will be obliged to admit that the cantatas are as instructive as they are entertaining and that one might use them to revive today that manner of instruction which was so commonly used among the ancients …

Seen from another perspective, however, Brossard's care to connect together the events relating to the murder could be said to celebrate one of La Motte's most important contributions as an advocate of the moderns – unity of interest. Indeed, Brossard shared with La Motte sympathy for the moderns while still holding great respect for the ancients. This can be observed in his poetic choices, and in particular in his connections with the poets that wrote for the Mercure galant, the literary journal and voice of the moderns through which he established his reputation as a composer of airs, as Manuel Couvreur has persuasively argued.Footnote 59

Jacquet de La Guerre proposes a different kind of overview (see Table 2b), one that betrays a concern not for goal-oriented linearity, but rather for framing the murder scene as the dramatic fulcrum, employing a major key (A major) to create bookends to the main action, and minor keys (A and E) to connect the murder and the events that lead up to it.Footnote 60 This recalls the overall chiastic layout (A–B–C–D–C′–B′–A′) of the original story from the Apocrypha (Judith 8–16), which, Toni Craven points out, privileges the scene of the murder (labelled with the letter D) ‘as the narrative heart of the story … [in which] both form and content signal the climactic significance of Judith's triumph over Holofernes’ (see Table 3).Footnote 61 The central section in minor keys corresponds to the crucial moments leading up to the murder, in which Jacquet de La Guerre employs instrumental music to linger over and delay the action. This draws the listener in and lets him savour the pending deed rather than rushing through it like Brossard, thus recalling the focalizing stance of Caravaggio's maidservant looking into the painting to orient the vision of the beholder. Also focalizing are the lush musical moments provided by instrumental interludes and instrumental accompaniments – the sleep, the murder and the musical images of Holofernes, the narrator and Judith – that slow down narrative in exchange for prolonging musical time, which tends to warp La Motte's original narrative vision. Similarly, her musical prolepses and analepses – forecasting the future and evoking the past – also bypass La Motte's narrative control. Jacquet de La Guerre's attempts to focalize the scenario by imparting a voice to Judith can be perceived as a way of bypassing La Motte's characteristic reduction of a main character's direct speech to the third person (and thus to narratorial control), as observed above.

Table 2b Jacquet de la Guerre, Judith (1708)

Table 3 Chiastic structure of Judith 8–6 (from Toni Craven, ‘Artistry and Faith in the Book of Judith’, Semeia 8 (1977), 88)

This reflects the stance of someone assertive and aware of her own talent. Compared to Brossard – his musical training as an autodidact, his provincial and peripheral activity outside the king's established musical circles, and his open uneasiness with regard to the court – Jacquet de La Guerre was indeed in a different league.Footnote 62 She benefited from a proper musical training, undertook all sorts of musical genres (including opera), felt at home at court and enjoyed a privileged status there.Footnote 63 Introduced by her father to the court of Louis XIV at the age of five, she quickly gained the reputation of child prodigy for her dazzling ability as a keyboard player, and benefited from the sponsorship and protection of living at court during her early years.Footnote 64 A look through the various avertissements and prefaces to the music she dedicated to the king yields a picture of a woman on the one hand eager to please her patron, on the other self-aware and often pleased with her own talent and success, particularly in view of her unrivalled status as the first successful female operatic composer in France.Footnote 65 The Preface to her sacred cantatas (dedicated to Louis XIV) is particularly informative, in that it demonstrates both her confidence and her aesthetic vision about such pieces:

J'y ay fait un usage de la Musique digne, j'ose le dire, de VOTRE MAJESTÉ. Ce sont les faits les plus considérables de l'Ecriture Sainte que je mets sous ses yeux; L'Auteur des Paroles les a traitez avec toute la dignité qu'ils exigent, & j'ay tâché par mes Chants d'en rendre l'esprit, & d'en soûtenir la grandeur.Footnote 66

In it [my works] I have made a musical work worthy, dare I say it, of YOUR MAJESTY. These are the most significant deeds of Holy Scriptures that I put before your eyes; the author of the text has treated them with all the dignity that they require, and I have tried by my melodies to do justice to their spirit and to support their grandeur.

This is quite different from Brossard's pragmatic conception of the cantata as instructive and entertaining. The highly dramatic, strongly visual language of her Preface – ‘putting before your eyes’, ‘doing justice to their spirit’, ‘supporting their grandeur’ – implies music that greatly intensifies the text by making the scriptures come alive before the eyes (and ears) of the listener. Indeed, her sacred cantatas were held in such esteem and became so popular that manuscript copies travelled well beyond the French court: some even reached New France (Québec) in the eighteenth century.Footnote 67

The notion of supporting the ‘grandeur of the scriptures’ and ‘doing justice to their spirit’ might also help us contextualize and understand Jacquet de La Guerre's endorsement of the Judith character and her treatment of the murder as heroic. While much less radical than Gentileschi's representation of Judith, Jacquet de La Guerre's heroic portrayal and empowerment of her follows a pattern within the composer's own sacred cantatas in which unusually vivid musical characterization of Biblical women can be found.Footnote 68 Her support of the Judith character also continues a French literary and artistic tradition endorsing the notion of strong women – les femmes fortes – of which the rise in popularity of the Judith story represents an example.Footnote 69 In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries alone, three heroic poems and five spoken tragedies were dedicated to the Biblical heroine, while the eighteenth century saw the production of seven spoken tragedies and an opera libretto.Footnote 70 More striking than the sheer number, however, is the fact that two of these works were written by womenFootnote 71 and that three were dedicated to women, including Jeanne d'Albret, Queen of Navarre, the original leader of the Huguenots.Footnote 72 This French interest in femmes fortes was also promoted through cycles of paintings such as that commissioned by Marie de' Medici at the Luxembourg Palace, painted by Rubens, or that commissioned by the Maréchal de la Meilleraye for his wife in 1637, painted by Simon Vouet for the Hôtel de l'Arsenal (now Bibliothèque), among which Judith, Esther, Semiramis, Mary Stuart, Joan of Arc and others figure notably.Footnote 73

Taking thus into account the composers' different backgrounds and aesthetic perspectives, it remains to discuss their musical treatment at the local level of musical rhetoric. While both composers employ the normal parameters for the proper rhetorical articulation of the text's syntactical structure – rhythmic and melodic motion, and, in particular, key changes and modulationFootnote 74 – Jacquet de La Guerre's unique use of the melodic element either to enliven the text in the vocal line or to create an entirely separate discourse from it in the bass or in the obbligato instruments sets her music apart from Brossard's. This can be observed in the opening recitative and aria, which concern the general Holofernes and the city of Bethulia (numbers 1 and 2 in Table 1). Both composers employ rhythmic anapaests to depict the Assyrian general as an obstinate and goal-driven character. Yet Brossard simplifies and condenses La Motte's threefold division of the starvation of Bethulia, Holofernes's lavish banquet and his infatuation by setting the associated verses in two related key areas – C minor and E flat major (see Table 1). Jacquet de La Guerre complicates the situation with a more dynamic treatment. After beginning the recitative in A major, she begins modulating towards E via its dominant, B. The bass line in particular seems to tell a different story about Holofernes: its long plunge from dominant to tonic, B to E, carefully calibrated by the brief circle-of-fifths progression from E to B to F♯ at bars 3–4 and by the long bass descent, sidesteps and forgoes La Motte's threefold organization, and points instead to the leader's inexorable downfall (see Example 1). The dynamism of the circle-of-fifths progression renders the harmonic move towards E seemingly inevitable: the strong hint of minor mode implied by the G♮s in the continuo and soprano (bar 8) before the final cadence is significant from a narrative perspective, as it foreshadows the key of the murder by linking it with the true source of Holfernes's downfall – his infatuation for Judith.Footnote 75 The two composers' divergent views continue in Holofernes's aria ‘Victory Alone’, his declaration of love (number 2 in Table 1). Brossard's use of C minor and lilting dance rhythms and the expressive label tendrement paint Holofernes as a tender character easily vulnerable to infatuation (see Example 2); conversely, Jacquet de La Guerre's use of A major and Italianate features, including driving rhythms, sequences and extended melismas on ‘gloire’, depict him as overconfident and narcissistic (see Examples 3, 4a and 4b).

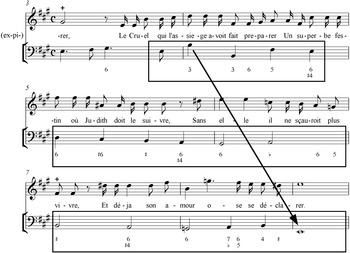

Example 1 Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Tandis que de la faim’, bars 3–9, from Judith (Ballard, 1708). Facsimile in The Eighteenth-Century French Cantata: A Seventeen-Volume Facsimile Set of the Most Widely Cultivated and Performed Music in Early Eighteenth-Century France, ed. David Tunley (New York: Garland, 1990), volume 3, 126–131. Used by permission

Example 2 Sébastien de Brossard, ‘La seule victoire’, bars 1–13, from Judith ou La mort d'Holofernes. Sébastien de Brossard, ‘Recueil de cantates’, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Ms F-Pn Vm7 164 (no date), available for consultation at <http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1050644> (1 July 2011). Used by permission

Example 3 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘La seule victoire’, bars 1–11, from Judith

Example 4a Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘La seule victoire’, bars 51–56, from Judith

Example 4b Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘La seule victoire’, bars 63–66, from Judith

Let us now turn to the preparation for the murder. This begins with La Motte's narrator goading Judith to act swiftly and take advantage of Holofernes's self-assurance and inebriation (numbers 3 and 4 in Table 1). Brossard here reflects the syntactical polarization of La Motte's verses through a dutiful rhetorical treatment of the text: he sets the verses in a récitatif simple, and relies on the establishment of distinct key areas (C minor and E flat major) to paint the narrator's incitement of Judith to cast sexy looks and to hasten Holofernes's drunkenness, on the one hand, and Holofernes's tender infatuation and eventual surrender to love and wine, on the other. Conversely, Jacquet de La Guerre animates the narrator with music that depicts his ever-changing moods as he becomes more involved in the description of the scenario, varying the text-setting from syllabic to melismatic and the continuo accompaniment from simple to mesuré. Particularly remarkable is the sudden profusion of vocal ornaments over a moving bass line in bars 2–3 of Example 5, which affords a glimpse of Judith's eroticism and allure that not even the narrator might otherwise be aware of, and the mesuré texture on ‘Hâtez l'yvresse’ in bars 4–8, which suggests a certain trepidation over Holofernes's impending inebriation and capitulation. It is once again through a descending bass line, however, that Jacquet de La Guerre can bypass La Motte's narrator and foretell the inevitable fate of Holofernes by highlighting the agents of his eventual downfall – love, wine and sleep (number 4 in Table 1). Particularly poignant are the two descending tetrachords (bracketed in Example 6), one diatonic on the notions of love and wine, the other chromatic on the notion of sleep. The use of chromaticism to paint sleep as a premonition of death is a particularly remarkable example; it is notable that a strong hint of E minor (implied by the G♮s in the continuo and voice at bars 6 and 8–9), the murder key, occurs towards the end of the recitative.

Example 5 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Enfoncez le trait’, bars 1–8, from Judith

Example 6 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Ne le voyez-vous pas’, bars 1–10, from Judith

The slumber scene as a preparation for the murder also shows the two composers' differing perspectives. Brossard treats it conservatively, creating what recalls a typical operatic sommeil. Indeed, the treble parts playing stepwise in slurred pairs recall Lully's slumber scene from Atys, as do the long held notes in the voice under key words like ‘repos’ (see Examples 7a and 7b). The overall effect is powerfully hypnotic, enhanced by the slow harmonic rhythm. Jacquet de La Guerre opts instead for an instrumental sommeil inserted between strophes – an unusual choice by the compositional standards of the time. The music itself is also uncharacteristic: instead of the stepwise pairs of crotchets in the treble parts moving over a slow-moving bass, Jacquet de La Guerre opts for instrumental parts that move independently in alternating thirds (see Example 8). The movement also lacks the still harmonic rhythm so typical of sommeil movements, featuring instead meandering harmonic and melodic motion, overarching melodies and a remarkable scarcity of internal cadences. It opens in A minor, yet the composer denies a firm cadence in the tonic key. Rather, through an arching melodic line in the violin (bars 1–12), which unfolds slowly and meanders harmonically, she whets the listener's appetite for a perfect cadence. Such a cadence, however, does not occur until bars 17–18, eighteen bars into the movement, and in an unexpected key, the dominant minor (E); the listener must wait until the very end of the movement to hear a perfect cadence in the tonic key (not shown). The composer also denies closure, mitigating the effect of a perfect cadence by immediately turning away from the presumed arrival of the new tonic and continuing on towards a new key, as can be seen in bars 27–29, where the modulation to D minor is thwarted by the f♯1 and the g♯1 in the ascending violin line, which point back to A. All of this creates a sense of waxing and waning that feels disquieting rather than hypnotic.

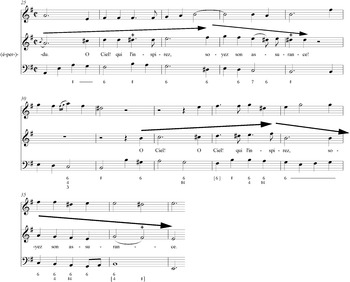

Example 7a Brossard, ‘Sommeil’, bars 1–13, from Judith ou La mort d'Holofernes

Example 7b Brossard, ‘Sommeil’, bars 53–59, from Judith ou La mort d'Holofernes

Example 8 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Sommeil’, bars 1–30, from Judith

Catherine Cessac suggests that Jacquet de La Guerre's textless setting of the sommeil is not as original as Brossard's canonic treatment.Footnote 76 I would argue the opposite, that her deliberate compositional choice allows this music to function at multiple levels precisely because it is not bound by the verbal domain. At the dramatic level, the sommeil paints the moment of Holofernes's inebriation and capitulation at the hands of Judith's powerful spell. Indeed, the winding phrases and the constant denial of closure can be understood as hallmarks of Judith's deceitful seductive powers. At the narrative level, the music functions as the equivalent of an extended verbal description – an ekphrasis, precisely that which La Motte enjoyed removing – which has the effect of slowing down or pausing dramatic time in order to set up properly the ensuing murder.Footnote 77 There is yet another level, however, one that yields the perception of this piece as a type of focalization. Much like the uneasiness expressed by the voyeuristic posture of Caravaggio's maidservant, who invites the beholder to participate in her own satisfaction over the deed, Jacquet de La Guerre invites the listener to peruse the scenario slowly through the uneasiness of the winding melodic phrases and the nonteleological harmonic language in a way that recalls a travelling shot during a film, urging the listener to contemplate the significance of the moment rather than to take a standard sommeil image at face value.

The most divergent musical characterization deals with the portrayal of Judith immediately before the murder. Here La Motte highlights Judith's hesitation (number 6 in Table 1): notice, for example, the representation of her arm suspended in the air, as if it were temporarily frozen in time waiting for divine approval to strike its blow on Holofernes's head, or the narrator's plea on Judith's behalf for divine assistance to carry out the deed. Brossard matches La Motte's rhetorical depiction of the heroine's vacillation by highlighting each verse with a different key area (see number 6 in Table 1). Jacquet de La Guerre dignifies Judith's indecision instead and turns it into the expression of the heroine's noble determination in the face of her inevitable destiny. Her récitatif accompagné setting of La Motte's text employs certain ceremonial traits associated with French overtures and marches to portray royal characters, particularly the dotted rhythms and the anapaests, though in a slower tempo (shown in Example 9). Her treatment highlights Judith's internal conflict through the melodic tension between the voice and the bass line, whose descending melodic contour provides a grounding element with which the voice must contend. Every melodic ascent in the voice is invariably followed by a descent, as if the gravitational pull of the bass were impossible to resist.Footnote 78 This occurs at the opening, when the voice reaches a high g2 on ‘puissance’ in a progressive ascent followed by a descent to the dominant, emphasized by a Phrygian cadence on ‘demeure suspendu’ (see Example 10, bars 16–17). Likewise, the voice attempts another ascent on ‘elle frémit de la vengeance’, but is promptly cajoled by the bass to follow its descent on ‘soutenez’, which outlines a descending tetrachord – A–G–F–E – in augmentation (shown in Example 11). Two final chromatic ascents in the voice, to invoke Heaven's help, are also followed by descents (see Example 12). This treatment recalls the tension between voice and bass employed in French opera during ground-bass arias that Geoffrey Burgess has suggested were used to represent the hero's final deliberation before a critical decision.Footnote 79 Indeed, it recalls Jacquet de La Guerre's own treatment of the bass line (which features a descending tetrachord within a changing ground bass) and the voice in the opening section of Procris's monologue ‘Lieux écartés, paisible solitude’ in Act 2 Scene 1 from her opera Céphale et Procris, in which the heroine expresses her inner suffering at the threat of separation from Céphale and tries to find consolation in solitude.Footnote 80 By calling upon this practice Jacquet de La Guerre ennobles Judith's inner conflict by recasting it as the dilemma of a tragic heroine rather than as the whim of a weak character, thereby focalizing the heroine through her own view. At the narrative level, however, this explosion of descending thematic material in the bass – especially the descending tetrachord – feels like the culmination of the previous bass descents employed to allude to Holofernes's demise. Indeed, because of its frequency throughout the piece, the descending tetrachord acts as a leitmotif, a narrative tool that suggests that the destiny of Judith and the imminent death of Holofernes are inextricably linked.

Example 9 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Judith emplore encor’, bars 1–10, from Judith

Example 10 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Judith emplore encor’, bars 11–17, from Judith

Example 11 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Judith emplore encor’, bars 15–24, from Judith

Example 12 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Judith emplore encor’, bars 25–37, from Judith

As for the murder itself (number 7 in Table 1), Brossard expresses it through a particularly striking run-on move from recitative to instrumental prelude and a sudden modulation from C minor to A minor. This choice suggests Brossard's emphasis on swiftness of action, as if he consciously chose to de-emphasize the brutality of the moment by passing over it quickly (see Example 13). Only the semiquaver sequence, reinforced by the chromatically ascending bass line proceeding in dactylic rhythms (bars 10–13), briefly hints at the physical struggle between Judith and Holofernes before the striking of the final blow. This music functions as the ritornello of the ensuing aria ‘Le coup est achevé’, thereby diffusing the energy of the murder and catapulting the listener into the final celebration.

Example 13 Brossard, ‘murder music’, bars 7–17, from Judith ou La mort d'Holofernes

Conversely, Jacquet de La Guerre's music celebrates Judith's heroic determination in carrying out the murder, animating her valorous arm, as it were, and turning what La Motte depicted as suspended indecision into action. Though brief – only nineteen bars – the movement effectively portrays what feels like the determination of a soldier going to battle (see Example 14). This is achieved by the martial quality of the rhythm in the violins, assisted by a basso ostinato in relentless crotchet arpeggios; by the linear trajectory of the bass line, which proceeds at a rate of one chord per bar throughout most of the movement; and by the mechanical regularity of the modulating sequences, all of which create a sense of inevitability. This focalization on the execution implies Judith's calm yet resolute sense of purpose, and immortalizes her action in a seemingly never-ending moment. Such qualities recall Gentileschi's painting, in particular what Ciletti, Garrard and Bissell have noted about her portrayal of Judith as an instrument of war, reflected, as Ciletti argues, in the way the biblical character ‘exude[s] the confidence of someone secure in the virtue of her deed’.Footnote 81

Example 14 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘murder music’, bars 1–19, from Judith

The treatment of the post-murder celebratory aria (number 8 in Table 1) also shows the two composers' differing approaches. Concerned with continuity of action, Brossard diffuses the energy of the murder by turning the murder music into the ritornello of ‘Le coup est achevé’. His manipulation of La Motte's text also shows his concern for grouping together celebratory texts for the sake of dramatic unity: Brossard moves the aria's original second stanza – a recollection of Holofernes's death that does not fit within the celebration – to the cantata's final aria (represented in dotted arrows in Table 1) and adds a new recitative of his own invention to urge the citizens of Bethulia to continue the celebration (see asterisk in Table 1).

Jacquet de La Guerre strikes instead through her music alone, leaving La Motte's second stanza unscathed and capitalizing on the contrasts it creates with the first so as better to juxtapose Holofernes's demise and Judith's triumph. Brooke Green has noted that on the one hand Jacquet de La Guerre celebrates Judith's heroism through appropriate rhetorical devices – a fast tempo, a melodic line with wide leaps, a characteristic battle-music motif, which suggests a ‘warrior-masculine … androg[y]nous persona’, and long Italianate melismas on words like ‘triomphante’ that highlight and extend Judith's triumph in spite of La Motte's deliberate de-emphasis – while on the other hand the composer pays her respects to Holofernes's death in two brief minor-key sections, in which she slows down the tempo to lentement (see Example 15).Footnote 82 Green sees the contrast as ironic, and perceives the lentement as out of place and ‘fairly perfunctory’ since ‘a vite interferes as if Judith is dancing around with excitement or possibly even satirising [Holofernes's] “tragedy”’.Footnote 83 I would like to turn Green's idea upside down and suggest that from a narrative perspective it is more likely that Jacquet de La Guerre meant to evoke a brief interference of the tragic past within the triumphant present. I thus perceive the two brief lentement sections as narrative flashbacks, what Genette calls analepses: Jacquet de La Guerre's music thus not only pays its respects to Holofernes's death but also urges the listener to relive its memory, if only for a brief moment.

Example 15 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Le coup est achevé’, bars 33–42, from Judith

A final striking difference is the way the two composers treat the concluding aria ‘Chantons, chantons’, whose celebratory text provides a glorification of God and, by extension, Louis XIV. By manipulating La Motte's text, Brossard explicitly sets up a contrast between God's triumph and Holofernes's demise by excising the aria's original second verse and replacing it with two new ones – one of his own invention, the other taken from ‘Le coup est achevé’, as previously mentioned. He depicts God's glory in the opening verse as a bright, energetic rondo refrain in C major (seen in Example 16), which exhibits the very battle-music motif – as both anapaests and dactyls – that Jacquet de La Guerre ascribes instead to Judith; the exuberance of the refrain easily overwhelms the two restrained rondo couplets, set in the secondary keys of G major and A minor respectively, that paint Holofernes's defeat. And yet, despite the contrast, the music gives us a picture of Holofernes that is mainly sympathetic: Brossard indeed employs ‘royal’ battle-motifs (dactyls) that seem to cater to Holofernes's regal pride in the bass line of the G major couplet, almost portraying him as marching alongside the kingly celebration (see Example 17). Moreover, in spite of the musical contrast between the king and Holofernes, Brossard's pairing of the two male figures in the final aria seems almost to set Judith's personal triumph aside as the means to an end in a fashion that recalls the way in which La Motte also sidesteps the heroine by apostrophizing her and never allowing her to speak.

Example 16 Brossard, ‘Chantons, chantons’, bars 1–5, from Judith ou La mort d'Holofernes

Example 17 Brossard, ‘Chantons, chantons’, bars 31–35, from Judith ou La mort d'Holofernes

Once again, Jacquet de La Guerre leaves La Motte's text intact while delivering a different message through her music. Her version of ‘Chantons, chantons’ presents an apparent incongruity between the triumphant text and the rather anaemic character of the music glorifying the king (Example 18). Brooke Green notes that this is especially significant when compared with Jacquet de La Guerre's decisively more powerful portrayal of Judith's triumph in ‘Le coup est achevé’, and she perceives this as the composer's deliberate attempt at creating a destabilizing situation that seems to threaten conventional wisdom.Footnote 84 She notes that the king's musical language includes narrow intervals, a melody characterized by a long gradual descent and a syllabic setting of the text, in contrast to the wide leaps, battle-music motif and Italianate virtuosity of Judith's music.Footnote 85 Indeed, if one considers musical rhetoric, the king appears old and deflated compared to Judith's youthful vigour: his melismas on ‘victoire’ are slower and less flamboyant than hers, and the one he sings on ‘triomphe’ is oddly descending.Footnote 86 Green makes an excellent point when she argues that:

If we took Mattheson literally, it would seem that the real emotions here are sadness and even despair. We are told to “sing of the glory” (the King's glory) but this theme is simply not as uplifting as Judith's in Le coup est achevé. Furthermore, the sprightly tempo could imply a feeling of forced enthusiasm, and the result could even be interpreted as a half-hearted attempt by the narrator to encourage us to dutifully celebrate the King.Footnote 87

Example 18 Jacquet de La Guerre, ‘Chantons, chantons’, bars 1–12, from Judith

Yet rather than viewing this music as a veiled criticism of the king's power, which in light of Jacquet de La Guerre's personal debt to the royal family would be rather unlikely, it might be more appropriate to consider this aria as a witty critique of La Motte and his narrator. Indeed, the discrepancy between the written 3/4 metre and the 6/8 metre clearly demanded in performance by the phrasing, syllabic accents and agreement between treble and continuo, together with the hemiolas and cross-rhythms – all of which deliberately destabilize the performance – could be seen as a musical pun against the ‘stiffness’ of La Motte's narrator.Footnote 88 The resulting playfulness of this music seems to poke fun at him by making his performance appear altogether inappropriate and inadequate for upholding the required solemnity of the moment, the celebration of the king's glory. Moreover, the ‘feeling of forced enthusiasm’ of this music could also be viewed as a veiled mockery aimed at the narrator's infelicitous verse ‘And the weakest hand [Judith's] / Is sufficient for His [God's] miracles’, almost as if Jacquet de La Guerre wished to beat La Motte at his own game by questioning his final reservations about Judith's strength.

Conclusion

Brossard and Jacquet de La Guerre's settings of La Motte's Judith provide a remarkable case study of musical exegesis, showing two diametrically opposed perspectives on text setting. Brossard's conception of the execution as civic duty – a means to an end – yields a compressed dramatic time that fast-forwards the events, passing over the murder quickly and propelling the action forward towards the final triumph. Yet while his efficient dramatic structure gets the job done, it does not offer an individual perspective. It yields rather a bird's-eye view of the story that squares with La Motte's concept of unity of interest, according to which everything must be connected to a single, underlying idea. Brossard's efficiency of structure may recall Gentileschi's efficiency of execution, and his fidelity to La Motte the dutifulness of her maidservant; yet his overall message does not celebrate, as is the case in Gentileschi, ‘the legitimate aggressive deeds of the famous biblical character, heroic avenger of the Jewish people’.Footnote 89

In contrast, Jacquet de La Guerre achieves precisely that, acting as focalizer by zooming in on key moments of the story to propose a viewpoint that differs from that of La Motte's narrator, bypassing his agency so as to celebrate Judith's heroic deed as legitimate, ennobling the indecision ascribed to her by La Motte and turning it into action. Significantly, this is achieved through the branch of music that claims independence from the text – instrumental music. Her instrumental topoi can be said to be ‘plurifunctional’ in the sense that although they fulfil the normative mimetic roles suggested by the text, they also manipulate narrative time independently from the text: the descending tetrachord foreshadows Judith's deed, linking it with Holofernes's downfall;Footnote 90 the slumber music and the basso ostinato of the murder expand time to prepare the action and linger on its heroism respectively; and the sudden lentement in the last aria brings back past memories of the murder for the listener. Her conception of the scene yields a richly detailed, elaborately involved view, rather than the detached bird's-eye view of Brossard: she stretches dramatic time, rather than compressing it, allowing the listener to savour each moment, and to perceive the murder scene as the dramatic fulcrum. Through her music, Jacquet de La Guerre builds an emotional link with her listener and goads him to listen to and heed the action in much the same way that the spellbinding gaze of Caravaggio's maidservant drives the beholder to look and pay attention. Yet unlike Caravaggio's anaemic depiction of Judith, Jacquet de La Guerre's representation is powerfully heroic, and yields an overall message that celebrates Judith's heroism per se rather than viewing her action as a means to an end, thus continuing not only a trend in the composer's own cantatas, but also a longstanding French tradition of femmes fortes. Through music, which exhibits a strong narrative impulse either by playing a dramatic role between textual strophes or by greatly expanding on ideas put forth by the text, and by refusing to rearrange La Motte's text to achieve its dramatic purpose, as does Brossard, she demonstrates confidence in instrumental music as a narrative medium, thereby asserting her creative independence from the poet. This is very different from Brossard's music, which could be said to ‘colour’ La Motte's text, blending with it in a way that recalls what Le Cerf de la Viéville, a staunch supporter of the notion of music as subservient to the text, had called ‘re-painting’ the poetry, so that ‘the verse is indistinguishable from and lives again in the music’.Footnote 91

With its strong impulse to narrate and to represent the multifarious aspects of the character of Judith by relying primarily on instrumental music, Jacquet de La Guerre's work remains a unique, isolated case in the history of the cantata. Without attempting to force a case for a linear, historical trajectory, it is possible nevertheless to perceive in it certain preoccupations concerning music's potential for signification, for its ability to narrate and to create pictures that go beyond mimesis by inviting the listener to contemplate, preoccupations that strike a fundamental chord with similar mid-eighteenth-century concerns about music's expressive potential. Jacquet de La Guerre's faith in the ability of music, particularly instrumental music, to amplify the text to the point of bypassing it as a mode of expression foreshadows later eighteenth-century concerns – most evident in France through the writings of Jean-Baptiste Dubos, Charles Batteux, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot and others – with emancipating forms of artistic expression that rely primarily on the senses, such as painting and music, from the rational clutch of poetry.Footnote 92 This is most evident in the slumber music – where unconventional, undulating melodies and meandering harmonies engulf the listener in the sensuous beauty of its sound, inviting him to imagine a soundscape that far transcends that of the conventional sommeil topos prescribed by its text – and, to a lesser extent, in the murder music, with its basso ostinato that freezes the action into a seemingly never-ending moment. The simultaneously sensuous, visual and contemplative nature of this music matches the complexity of Judith: the music is in itself a paradox, expressing at once both action and reflection by depicting stasis through motion. In a passage from his L'Essai sur l'origine des langues, which reflects on music's ineffable powers of expression, Jean-Jacques Rousseau points precisely at this aspect:

C'est un des grands avantages du musicien, de pouvoir peindre les choses qu'on ne saurait entendre, tandis qu'il est impossible au peintre de représenter celles qu'on ne saurait voir; et le plus grand prodige d'un art qui n'agit que par le mouvement est d'en pouvoir former jusqu'à l'image du repos. Le sommeil, le calme de la nuit, la solitude, et le silence même, entrent dans les tableaux de la musique … Que toute la nature soit endormie, celui qui la contemple ne dort pas …Footnote 93

One of the great advantages of the musician is to be able to paint things that we cannot hear, whereas it is impossible for the painter to represent what we cannot see. The most prodigious feat of an art that acts primarily through movement is to be able to create the impression of rest. Sleep, the calm of night, solitude and even silence enter into the tableaux of music … Even if all of nature is asleep, he who contemplates it is not …

Rousseau's closing comment points to a final, significant aspect of this music – the fact that it commands the listener's attention. The contemplative aspects of Jacquet de La Guerre's sommeil and murder music could be said to anticipate another mid-eighteenth-century theme: the importance of absorption. This aspect has been discussed by Michael Fried in the context of mid- to late eighteenth-century French paintings and by Tili Boon Cuillé with regard to literary tableaux from the same period. These tableaux foreground ‘a musical performance staged for a beholder inscribed within the text’ as a mode of discourse to affect the emotional impact of the narrative.Footnote 94 Much like the paintings of Greuze, in which the figures are absorbed in the task at hand to the extent that they draw the beholder into the painting with them, Jacquet de La Guerre's music draws the listener in. In similar fashion, a literary tableau suspends the narrative momentarily to allow the inscribed beholder to become enraptured by the musical performance and listen not so much to the music as to the ‘emotion it expresses’ and ‘the characters whose sentiments the music evokes’.Footnote 95

Jacquet de La Guerre's interest in Judith's interiority and complexity of character may be what pushed her to take such bold steps into the realm of musical expression, steps in directions prescient of later eighteenth-century concerns. Yet her unusual position as a successful woman composer in France may well have played a role, too, in shaping her unique point of view. However that may be, the case of this cantata demonstrates her compositional prescience in truly understanding the ineffable power of music.