INTRODUCTION

Following journalistic best practices, let's not bury the lead – CJEM is creating a dedicated section for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety (QIPS) publications. CJEM now joins a growing movement to accept QIPS work, and it is among the first Canadian peer-reviewed medical journals to do so. This emergence of QIPS in CJEM and other journals speaks to both the demand for articles addressing quality and safety issues by readers and the number of projects being conducted in the clinical setting.

The creation of a dedicated QIPS section demonstrates the visionary leadership within the CJEM editorial team. Despite ongoing debates on the best methodologies to apply to a variety of challenges between research and implementation,Reference Mondoux and Shojania1CJEM has recognized that there is a place and need for improvement science to be applied in the clinical environment and disseminated more broadly. As the science of QIPS continues to expand, we foresee an increase in publication demand and in the types of articles to be included in this section. We also expect a commensurate need to include a greater number of healthcare providers with expertise in QIPS as peer reviewers and as decision editors. Lastly, we recognize the opportunity for CJEM to take a role in the education of emergency medicine (EM) learners and practitioners in the critical appraisal of QIPS work.

What is quality improvement and patient safety?

The field of QIPS focuses on systematic formal approaches to improving health services. Quality improvement (QI) is defined by Accreditation Canada as “the degree of excellence; the extent to which an organization meets their clients’ needs and exceeds their expectations.”2 Most take this definition further based on the Institute of Medicine's report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, and believe that all QI work should improve at least one of the dimensions of healthcare quality: safety, timeliness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and patient centredness.3 QI can occur at three organizational levels: the micro level (level of patient care and the frontline clinical team), the meso level (level of the organization), and the macro level (level of the region).Reference Chartier, Vaillancourt, Cheng and Stang4 While patient safety is often considered a pillar of quality, it also has its own unique definition and associated body of literature. The Canadian Patient Safety Dictionary defines patient safety as “the reduction and mitigation of unsafe acts within the healthcare system, as well as through the use of best practices shown to lead to optimal patient outcomes.”2 All QIPS work supports creating a culture where improvement opportunities are sought in every process in healthcare and where we constantly work to optimize these processes.

Why should quality reports be published separately from original research manuscripts?

At the heart of the difference between research and QI is a difference in the primary purpose of the project. The primary purpose of research is to discover new knowledge to be used in contexts other than where the research takes place. Research is designed to be generalizable and to answer questions that will guide the development of best practices. The primary purpose of QI is to put knowledge in practice to address a local problem and attempt to improve clinical outcomes or to create better patient care in areas where strong evidence may not exist. Research is generally constructed to answer a specific question or test effectiveness of a defined intervention. QI is constructed to test system changes in iterative cycles in order to reach a designated aim, learning from each test of change and modifying strategies based on learning. Improvement science uses unique methods and analytic strategies. It is a relatively new science to many readers. Having a unique section for QI reports will allow interested readers to more easily identify QI manuscripts and thereby promote the growth of this important field.

Why will this section matter to readers?

QIPS has transcended the early days of dogmatic checklist implementation and basic single-intervention before and after studies. In the 20 years since its inception,Reference Kohn, Corrigan and Donaldson5 the field of QIPS has continued to grow, as has the number of practitioners practising within and because of their expertise in QIPS. Adherence to the core tenets of the science and the inclusion of stronger study designs are becoming more ubiquitous. So, too, the venues for dissemination of knowledge that may benefit patients, providers and leaders must advance.

QIPS’ influence is felt more broadly than within journals. It has spurred the creation of communities of practice; academic symposia at national conferencesReference Chartier, Mondoux and Stang6; dedicated improvement and safety conferences; and new grants, awards, and salary support opportunities. Academic accreditation bodies have made QIPS competencies mandatory during training.Reference Mondoux, Chan, Ankel and Sklar7 Trainees are seeking expertise in this area, and postgraduate training opportunities in QIPS are flourishing. Recently, the Royal College of Physician and Surgeons of Canada also approved an Area of Focused Competency (AFC) in QI.

Perhaps most notably, Canadian EM physicians are on the leading edge of important QIPS work nationally and internationally.Reference Cooke, Duncan and Rivera8–Reference Vaillancourt, Seaton and Schull10 The CJEM readership will now be able to access practice-changing work from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP), and CJEM can further extend its influence into practice environments looking for innovative ways to improve quality and safety in EM. Because QIPS outcomes are highly influenced by local contextual factors, providing readers with detailed information on specific interventions within their local context and their impact on patient outcomes is necessary in order for improvements to be replicated and spread. Many barriers to best-practice care delivery are similar across practices and geographical borders, and both patients and systems are often more similar than they are different. It behooves us to learn from one another to optimize our opportunities for success.

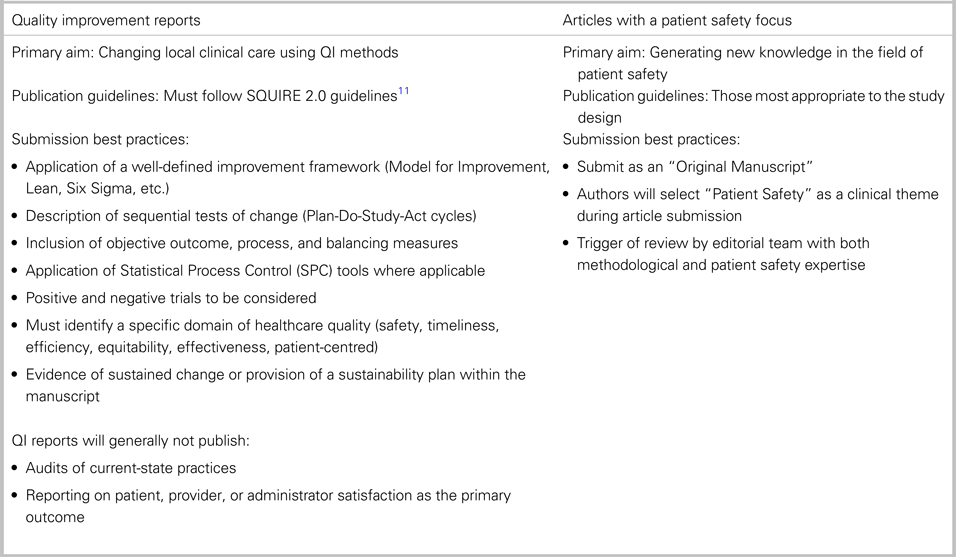

QI reports will accept manuscripts with a primary aim of improving local clinical care using QI methods such as Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles and statistical process control charts. Patient safety manuscripts may be published in QI reports if the manuscript describes a QI project with an aim of improving patient safety. Patient safety research articles, such as observational or intervention studies that have a primary aim of contributing new knowledge to the field of patient safety, will be published with original manuscripts and will include a special designation of having a patient safety focus. Table 1 summarizes criteria for the submission of QI reports and articles with a patient safety focus.

Table 1. Guidelines for contributors for the submission to CJEM of quality improvement reports and articles with a patient safety focus

Setting the course

CJEM is delighted to provide this section to its readership. In its spirit of innovation and growing impact, QIPS content will provide value to clinicians at the point of care and ED administrators in the international audience. This builds upon the groundswell of QI work nationally and internationally. It will also be a venue for the publication of CAEP QIPS awards and conference abstracts. It provides the EM audience with a clear publication milestone for clinical improvement projects, allowing these to be disseminated and extending their reach beyond the local environment. The aspiration of CJEM is to publish a QIPS-focused issue in early 2020. The call is officially open, and we are looking to QIPS faculty nationally and internationally to consider CJEM as a preferred destination for publishing in QIPS.

INTRODUCTION

Following journalistic best practices, let's not bury the lead – CJEM is creating a dedicated section for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety (QIPS) publications. CJEM now joins a growing movement to accept QIPS work, and it is among the first Canadian peer-reviewed medical journals to do so. This emergence of QIPS in CJEM and other journals speaks to both the demand for articles addressing quality and safety issues by readers and the number of projects being conducted in the clinical setting.

The creation of a dedicated QIPS section demonstrates the visionary leadership within the CJEM editorial team. Despite ongoing debates on the best methodologies to apply to a variety of challenges between research and implementation,Reference Mondoux and Shojania1CJEM has recognized that there is a place and need for improvement science to be applied in the clinical environment and disseminated more broadly. As the science of QIPS continues to expand, we foresee an increase in publication demand and in the types of articles to be included in this section. We also expect a commensurate need to include a greater number of healthcare providers with expertise in QIPS as peer reviewers and as decision editors. Lastly, we recognize the opportunity for CJEM to take a role in the education of emergency medicine (EM) learners and practitioners in the critical appraisal of QIPS work.

What is quality improvement and patient safety?

The field of QIPS focuses on systematic formal approaches to improving health services. Quality improvement (QI) is defined by Accreditation Canada as “the degree of excellence; the extent to which an organization meets their clients’ needs and exceeds their expectations.”2 Most take this definition further based on the Institute of Medicine's report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, and believe that all QI work should improve at least one of the dimensions of healthcare quality: safety, timeliness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and patient centredness.3 QI can occur at three organizational levels: the micro level (level of patient care and the frontline clinical team), the meso level (level of the organization), and the macro level (level of the region).Reference Chartier, Vaillancourt, Cheng and Stang4 While patient safety is often considered a pillar of quality, it also has its own unique definition and associated body of literature. The Canadian Patient Safety Dictionary defines patient safety as “the reduction and mitigation of unsafe acts within the healthcare system, as well as through the use of best practices shown to lead to optimal patient outcomes.”2 All QIPS work supports creating a culture where improvement opportunities are sought in every process in healthcare and where we constantly work to optimize these processes.

Why should quality reports be published separately from original research manuscripts?

At the heart of the difference between research and QI is a difference in the primary purpose of the project. The primary purpose of research is to discover new knowledge to be used in contexts other than where the research takes place. Research is designed to be generalizable and to answer questions that will guide the development of best practices. The primary purpose of QI is to put knowledge in practice to address a local problem and attempt to improve clinical outcomes or to create better patient care in areas where strong evidence may not exist. Research is generally constructed to answer a specific question or test effectiveness of a defined intervention. QI is constructed to test system changes in iterative cycles in order to reach a designated aim, learning from each test of change and modifying strategies based on learning. Improvement science uses unique methods and analytic strategies. It is a relatively new science to many readers. Having a unique section for QI reports will allow interested readers to more easily identify QI manuscripts and thereby promote the growth of this important field.

Why will this section matter to readers?

QIPS has transcended the early days of dogmatic checklist implementation and basic single-intervention before and after studies. In the 20 years since its inception,Reference Kohn, Corrigan and Donaldson5 the field of QIPS has continued to grow, as has the number of practitioners practising within and because of their expertise in QIPS. Adherence to the core tenets of the science and the inclusion of stronger study designs are becoming more ubiquitous. So, too, the venues for dissemination of knowledge that may benefit patients, providers and leaders must advance.

QIPS’ influence is felt more broadly than within journals. It has spurred the creation of communities of practice; academic symposia at national conferencesReference Chartier, Mondoux and Stang6; dedicated improvement and safety conferences; and new grants, awards, and salary support opportunities. Academic accreditation bodies have made QIPS competencies mandatory during training.Reference Mondoux, Chan, Ankel and Sklar7 Trainees are seeking expertise in this area, and postgraduate training opportunities in QIPS are flourishing. Recently, the Royal College of Physician and Surgeons of Canada also approved an Area of Focused Competency (AFC) in QI.

Perhaps most notably, Canadian EM physicians are on the leading edge of important QIPS work nationally and internationally.Reference Cooke, Duncan and Rivera8–Reference Vaillancourt, Seaton and Schull10 The CJEM readership will now be able to access practice-changing work from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP), and CJEM can further extend its influence into practice environments looking for innovative ways to improve quality and safety in EM. Because QIPS outcomes are highly influenced by local contextual factors, providing readers with detailed information on specific interventions within their local context and their impact on patient outcomes is necessary in order for improvements to be replicated and spread. Many barriers to best-practice care delivery are similar across practices and geographical borders, and both patients and systems are often more similar than they are different. It behooves us to learn from one another to optimize our opportunities for success.

QI reports will accept manuscripts with a primary aim of improving local clinical care using QI methods such as Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles and statistical process control charts. Patient safety manuscripts may be published in QI reports if the manuscript describes a QI project with an aim of improving patient safety. Patient safety research articles, such as observational or intervention studies that have a primary aim of contributing new knowledge to the field of patient safety, will be published with original manuscripts and will include a special designation of having a patient safety focus. Table 1 summarizes criteria for the submission of QI reports and articles with a patient safety focus.

Table 1. Guidelines for contributors for the submission to CJEM of quality improvement reports and articles with a patient safety focus

Setting the course

CJEM is delighted to provide this section to its readership. In its spirit of innovation and growing impact, QIPS content will provide value to clinicians at the point of care and ED administrators in the international audience. This builds upon the groundswell of QI work nationally and internationally. It will also be a venue for the publication of CAEP QIPS awards and conference abstracts. It provides the EM audience with a clear publication milestone for clinical improvement projects, allowing these to be disseminated and extending their reach beyond the local environment. The aspiration of CJEM is to publish a QIPS-focused issue in early 2020. The call is officially open, and we are looking to QIPS faculty nationally and internationally to consider CJEM as a preferred destination for publishing in QIPS.

Competing interests

None declared.