1. Introduction

‘For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.’Footnote 1 This is what Derek Parfit has nicknamed the repugnant conclusion. He speaks of the world with the ten billion people as the A world and the world with many people with lives barely worth living as the Z world. Some ‘total’ views such as utilitarianism imply that the Z world is better than the A world (they imply the repugnant conclusion) and explain morally why this is so. The moral explanation according to utilitarianism, for example, is that the Z world contains a larger sum total of happiness than does the A world. Other total views, as we will see, such as prioritarianism, provide competing moral explanations of why the Z world is better than the A world; prioritarians do so with reference to the maximisation of a weighted sum of happiness. This implication from total views has been rejected by Parfit and he has tried in vain to find some plausible theory in population ethics that can avoid it.

2. For better or worse

Here a note on the words ‘better and worse’ is in order. Since we are here dealing with moral problems (not problems in aesthetics) I take it that the talk about one world being better or worse than another one has normative implications. If not, I find no way of forming any intuitions at all in population ethics. In particular, I will assume that if a world A is better than a world B, and if I can produce one and only one of them, I ought, all other things being equal, to produce A. This means that, if I can produce A rather than B without violating any normative constraints (I need not kill innocent beings when I do so, I need not break any promises, and so forth), then I ought to produce A rather than B. Such normative implications are what feeds my intuitions in the field.

3. Strong arguments in favour of the repugnant conclusion

I happen to believe the repugnant conclusion is true. And I am a bit annoyed by the slander it has come under. The rhetoric in the area of population ethics is rich. Here we meet not only the ‘repugnant’ conclusion, but also slurs such as the ‘very’ repugnant conclusion, and the ‘sadistic’ conclusion, to name just a few. I will avoid this kind of rhetoric in this short comment. My focus is on the truth or falsity of the conclusion. Is the Z world better or worse than the A world?

It is of note that strong arguments count in favour of the truth of the conclusion that Z is better than A. Here is, in my mind, the most compelling one among them. It is implicit already in Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons, even though he never used it as an argument in defence of the repugnant conclusion. I used it to that effect in my 2002 paper.Footnote 2 Michael Huemer, who has also invented the helpful term ‘benign’ addition, which I will now use, has given a similar argument in defence of the repugnant conclusion more recently.Footnote 3 In my original statement of the argument, it trades on the possibility of moving from the A world to the Z world in a series of steps that are clearly, each one of them, an improvement of the situation. The idea is simple. We start with the A world. We move to the B world where those who inhibit the A world are still with us. We improve their situation. At the same time we add a large number of people with lives worth living, even if they are not as happy as the original people. In the next step we level out differences between people in the B world in a manner that means that those who are best off lose less than those who are worst off gain (there is an equal number of each category); at the same time we add a large number of people, living lives worth living but not as good as the lives lived by the rest (the added people are just as many as the already existing, ‘necessary’Footnote 4 ones). And we do this over and over again until we have reached something close to the Z world.

It makes moral sense to argue that each move here means improvement. In the first step from the A world to the B world we can rely exclusively on the observation that it means that those who are affected together gain from the move and the observation that the people we have added are grateful for being around. In the next series of steps we note that each consecutive move is also an improvement in that those who are worse off gain more than those who are better off lose (confining the comparison to necessary people, living in both outcomes under comparison), leaving everyone at exactly the same level of happiness. What is the egalitarian to say of the addition of happy people in each step? After all, it introduces new inequalities.

I think the egalitarian should accept this since, had the move not been made, these additional people would not have existed. Now that we have added them, they are there, and they are grateful for being around. So they have no complaint to voice against the existing situation.

This is just one among several arguments in defence of the repugnant conclusion. Not only do compelling arguments for the truth of the repugnant conclusion exist, however. It has also proved to be extremely difficult to find some reasonable theory that avoids it. For a review of the alternatives, see the Stanford Encyclopedia entry on this.Footnote 5

We have good reasons, then, to consider the possibility that the repugnant conclusion is true. But in that case, what are we to do with the intuition, held by some, that it is not only false, but obviously false? We should see if we can debunk it.

4. Debunking moral intuitions

In my discussion I take it for granted that there are true and false answers to the questions raised in population ethics.Footnote 6 How can we arrive at these answers? We have to rely on our moral intuitions, I submit. A moral intuition is an immediate judgment to the effect that this is right, or wrong, or morally obligatory, which can have theoretical content but which is not derived from the theory under test. The content of our moral (normative) intuitions gives us evidence for our moral conjectures. The conjecture that best explains the content of an intuition gets support from it through an inference to the best explanation. The content of a recalcitrant intuition can also function as conclusive evidence against a moral conjecture. This is how the intuition that the A world is better than the Z world is taken by Parfit as evidence against total views such as utilitarianism (implying that the Z world is better than the A world).

Not all intuitions are reliable, however. We should submit each of them to what I have called cognitive psychotherapy.Footnote 7 We should learn as much as possible about their origin. Only if they survive the knowledge provided by such therapy should we rely on them. We may think of this as a credential test. There are actually two ways in which they can fail this test. They can simply go away once we know how we have arrived at them, or they can stay, but appear to us as robbed of any evidential value (as the stick in water that still looks bent to us when we have learned about optic theory). In the present context I will give examples of both these effects when I try to show that we should debunk our intuition (if we hold it) that the repugnant conclusion is false. If they survive the test, we may speak of them, borrowing a phrase from John Rawls, as considered moral judgments.Footnote 8

5. Some general debunking strategies

In our discussion about the repugnant conclusion we should rely on some general debunking strategies. The most obvious one is this. We must guard ourselves against asking ourselves: in which world would I like to live? The A world or the Z world? The answer to this question is obvious but it should also be obvious that it is irrelevant to the question of which world is the best one. If we should solve the normative question by any consideration of this sort, then we should add that while it is probable that, if we opt for the Z world, we would come to live there, if we opt for the A world, it is highly unlikely that we will do so. When we realise this the intuition tends to go away.

Another obvious debunking strategy has to do with our capacity for handling, in our moral imagination, large numbers. Several authors such as John Broome have used it to debunk the intuition that the A world is better than the Z world. We cannot morally imagine what is at stake when we consider the Z world.Footnote 9

The human population is expected soon to reach the number of the inhabitants of Parfit's A world (ten billion people). This invites the following thought. What if we conceive of the A world as the happy ending of sentient life on earth in a near future, where we use up all available resources, and the Z world instead as the continuation for millions of years of it, with billions of billions of inhabitants, conserving available resources and living poor lives but lives worth living? Then the intuition that the A world is better than the Z world might well go away.

The present writer and others have also noted that we may overestimate the value of our lives. Perhaps the lives in the Z world are like ordinary lives, with ups and downs, ending up perhaps at a sum total of + 1 hedon? Perhaps many ordinary lives are worth not living? In that case, the Z world is perhaps not so bad after all, not even in comparison with the A world.Footnote 10

Considerations such as these should give those philosophers pause who find the repugnant conclusion to be obviously false. This does not mean that in the place of this intuition there enters an intuition to the opposite effect: The Z world is better than the A world. To the extent that anyone holds this view it is likely that it has been derived from some theory such as total utilitarianism. This does not mean that it is false but it means that it lacks evidential value. It is not a considered moral judgement.

This is all well known. Now I turn to some new observations about how to debunk the intuition that the Z world is worse than the A world.

6. The principle of unrestricted instantiation

In his book Reasons and Persons (from which the quote above was taken) Parfit seems to take for granted that, in the abstract, the Z world is worse than the A world. And he seems to take for granted that most people share his view. That's why he goes to great lengths to find an alternative to the total view, an alternative view avoiding the conclusion that the Z world is better than the A world. I am not certain that most people do share his intuition. In particular, I believe many are prepared to give it up, or stop taking it as evidence, already for reasons given in the previous section. However, there is a more general problem with the intuition that I will now discuss. We should rely on the abstract intuition that the Z world is worse than the A world only if the intuition holds for whatever concrete instantiation of the conclusion we focus on. If we need a special instance of it in order to reach the conclusion that the A world is better than the Z world, then we are not dealing anymore with the original argument from the repugnance of the repugnant conclusion. Instead we are relying on some special aspects of the case that need to be discussed separately.

I take the principle of unrestricted instantiation to include the thought that the repugnance of the repugnant conclusion does not depend on any special idea about what it is that makes a life go well (for the individual living it). Parfit starts out by discussing the repugnant conclusion in simple hedonistic terms, but he adds that the Z world could represent a world where ‘there is the greatest quantity of whatever makes life worth living’.Footnote 11 His graphs require that some kind of measurement can be made of whatever it is that makes a life worth living. It is easier for a hedonist to satisfy this requirement than for a theorist who adds that all sorts of things on an ‘objective list’ aside from happiness matter as well. Parfit assumes, when he takes the first step down the moral alphabet, that the life in the B world is more than half as much worth living as the life in the A world, but he adds that such judgments cannot ‘in principle’ be precise.Footnote 12 Being myself a hedonist, I will allow myself to speak in terms of happiness (this is, I believe, what it's all about), but those who beg to disagree with me may in line with how Parfit introduced the repugnant conclusion transform my arguments into the currency they prefer. I will also assume that we can measure happiness on an interval scale with a unit, the hedon, which in principle, at least, we can count. It makes sense, then, that the sum total of happiness in a life is + 1. And, finally, in my discussion I will not restrict my interest to people; all sentient beings are of importance in the present context.

This principle of unrestricted instantiation is a reasonable heuristic device to abide by, in the discussion. When we find that our intuition that the A world is better than the Z world, if we have it, derives from some special features of any of the worlds, then these features merit a special examination and the problem, if there is one, may have nothing to do with large numbers. It might be possible to tend to these special concerns without giving up on the repugnant conclusion as such, as will be demonstrated in this article.

This is not to deny that simple logical point that if there exists one single instance of the A world such that no Z world is better than it, the repugnant conclusion is false. However, the ‘repugnance’ of it is something different. It resides in the thought that an A world could never be worse than a Z world. This is something we can supposedly sense, once we assess the abstract schema represented by the graph. We need not enter into details about the case.

I confess that I have difficulties imagining the lives of the extremely happy individuals in the A world. And I agree, as noted above, that the lives in the Z world may be rather like ordinary lives among people living in well-ordered states. The intuition that the Z world is worse than the A world hence falters. One of the relata, the Z world, is not as bad as one may have imagined, after all, and the other one, the A world, is difficult to fathom.

Be that as it may, a way of making sense of what it means to live in the A world could be to think of the large sum total of happiness in the lives in this world as the result of longevity. The A people live lives very similar to people in the Z world, but they go on with their lives for many hundreds of years while the people of the Z world live ‘ordinary’ lives, where the generations succeed one another. But then, is it really obvious that the A world is better than the Z world?

Or skip the restriction to people and think of the A world as inhabited by ten billion blue whales, living under conditions extremely propitious for their well-being. During a life-time of eighty years, all individuals feed by lunging forward at groups of krill, squeezing out the water and swallowing the food, never hungry, never worried, never being in a state of dreamless sleep (always at least semi-conscious), being thus an epitome of mindfulness. Suppose over their lifetimes they are garnering some + 1000 hedons. Think on the other hand of the Z world as populated by billions and billions of ordinary people like you and me, being unconscious during a third of their lives (while asleep). Add to this that these people are being depressed because of anxiety, unrequited love, bereavement when close ones are gone, and fear of the future for another third of their lives. Only during a third of their lives are they quite happy. All in all they end up on + 1 hedon.

Only if the argument from the repugnant conclusion survives in such instantiations should we be prepared to rely on it. I doubt that it does.Footnote 13

We could of course take the argument from the repugnant conclusion implicitly to target only the idea that for every world in which there is a large population leading lives rich in higher quality pleasures there is a world in which a much larger number of people enjoy no higher pleasures and just enough lower pleasures to make their lives worth living, which according to total views is better. On this reading of Parfit he doesn't target pure hedonistic theories in his argument from the repugnant conclusion. This violates the requirement of unrestricted instantiation, however. The whale world contains much happiness and fits well into the A world in Parfit's favoured graph. And I doubt that Parfit would have wanted to make this restricted use of his argument. After all, he starts out by stating the repugnant conclusion in simple hedonistic terms. On a personal note, I can report that, while I wrote my defence of hedonistic utilitarianism I spent a couple of weeks with Parfit at All Souls, discussing hedonistic utilitarianism 24/7 (this was the way he worked). I never sensed that hedonistic utilitarianism should not have been targeted by his argument from the repugnant conclusion. We should stick to unrestricted instantiation also with regard to theories about what makes a life go well, it seems to me.

And yet, it is of note that Parfit has supported his argument for the claim that the A world is better than the Z world with reference to a special perfectionist idea about superior value. When we move down the moral alphabet we at some point run up against a situation where all higher values are lost (such as the enjoyment of the music of Bach and Mozart as well as excellent food) and these values are now being exchanged for muzak and potatoes. When the higher values go away, the addition of more people doesn't compensate for the loss of quality in life.

This argument is clearly irrelevant to the present discussion of the repugnant conclusion. It violates the principle of unrestricted instantiation. We realise this when we realise that we can instantiate the repugnant conclusion in a manner where no such loss is made. The higher values could be absent both in the A world and in the Z world. The example with the whales illustrates this (we may assume with Parfit that all the higher values are gone in the Z world as he here conceives of it). Or, they can be present in the Z world while being absent in the A world (with the whales). More importantly, the higher values could be present in both the A and the Z worlds. On the assumption that the higher values are present also in the Z world, it is only that people there have to strive so hard for them that their lives end up at a sum total of happiness at + 1. In the A world people enjoy these higher values for free.

There may still be something to Parfit's idea of superior values, but this has nothing to do with large numbers and the repugnant conclusion, then.

Parfit was, or became, aware of this problem when he revisited the repugnant conclusion. He then raised the question:

Why is it so hard to believe that my imagined world Z . . . would be better than a world of ten billion people, all of whom have an extremely high quality of life?

And he answered:

This is hard to believe because in Z two things are true: people's lives are barely worth living, and most of the good things in life are lost.Footnote 14

And he went on to say:

Suppose that only the first of these was true. Suppose that, in Z, all of the best things in life remain. People's lives are barely worth living because these best things are so thinly spread. The people in Z do each, once in their lives, have or engage in one of the best experiences or activities. But all the rest is muzak and potatoes. If this is what Z involves, it is still hard to believe that Z would be better than a world of ten billion people, each of whose lives is very well worth living. But, if Z retains all of the best things in life, this belief is less repugnant.Footnote 15

This last sentence of the quoted passage comes close to giving up on the idea that the repugnant conclusion is repugnant as such. His concern is different and of a ‘perfectionist’ order. It can be spelled out without any reference to large numbers of people. He can accept that, if all the good things in the Z world are present, then the belief that the Z world is better than the A world is ‘less repugnant’. He should have admitted that it is not at all repugnant, it seems to me, but clearly he doesn't.

In his last published paper on the problem Parfit once again considers in passing the possibility of an instantiation of the Z world where there are higher values in both the A world and the Z world:

Suppose next that, in Roller-Coaster Z, everyone would live as long as everyone in World A, and all of the good things in these people's lives would be just as good, but these people's lives would be barely worth living because their lives would also contain much that was very bad. This version of Z also raises questions that I shall not discuss here. World Z, we can assume, would take a third, simpler form.Footnote 16

When assuming that World Z takes a simpler drab form (with muzak and potatoes) Parfit passes over the fact that his concern is not with the repugnant conclusion as originally stated, where pure hedonism is targeted as well as other theories of a meaningful life, but with a special perfectionist view about higher (superior) and lower values.Footnote 17

I take it that the repugnance of the repugnant conclusion has been successfully debunked. It is still of interest to discuss the idea of superior values. I will return to it below.

Before that, some words about the ‘very’ repugnant conclusion, however.

7. The very repugnant conclusion

This is how the ‘very’ repugnant conclusion is stated by Gustaf Arrhenius (who coined the term):

For any perfectly equal population with very high positive welfare, and for any number of lives with a very negative welfare, there is a population consisting of the lives with negative welfare and lives with very low positive welfare which is better than the high welfare population, other things being equal.Footnote 18

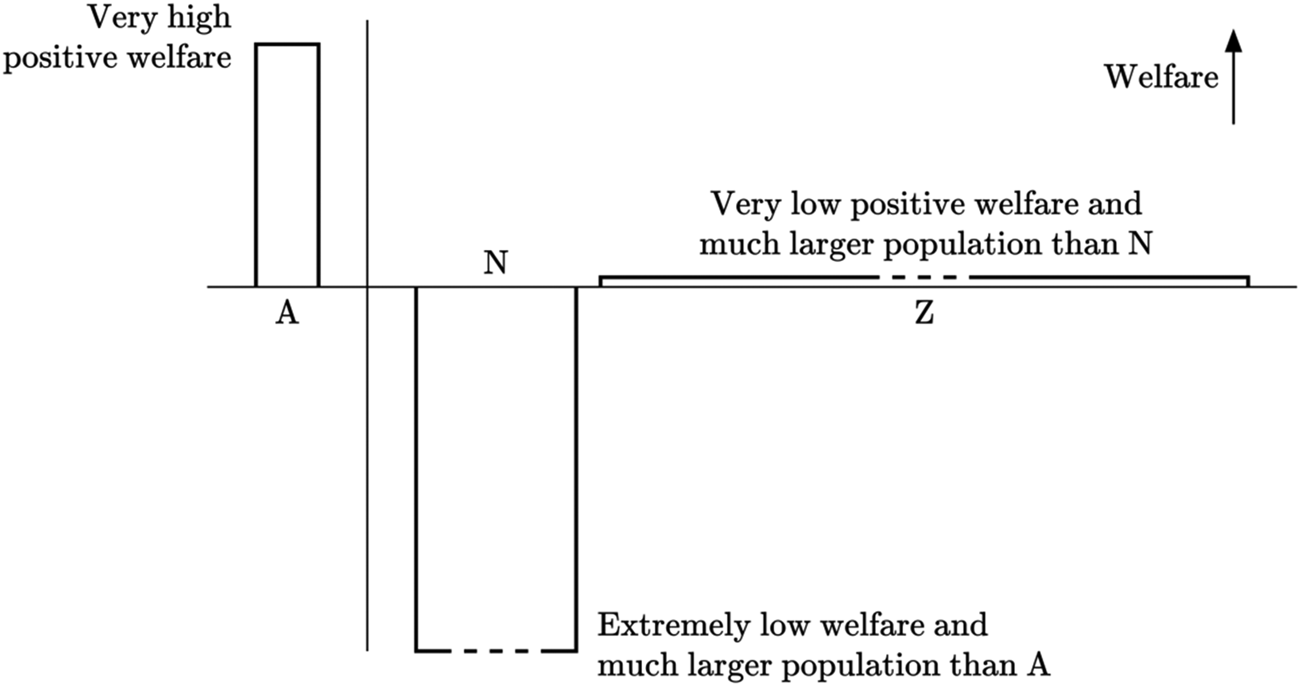

It can be illustrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1. The very repugnant conclusion.

If we adhere to the principle of unrestricted instantiation we may think of the people with very low positive welfare as people with very long lives, living lives similar to, but slightly worse than, the ones lived by ordinary people, only that they go on for such a long time. Suppose ordinary people live lives that sum up after 80 years, when they die, at +1. Suppose that the people with very negative welfare live similar lives, garnering every 80 years a net of −1 (rather than + 1), only that their lives go on for many hundreds of years. That's why their lives have very low welfare. If it is instantiated in this manner, I cannot see that the very repugnant conclusion adds anything of repugnance to the repugnant conclusion as such (which we have seen is not repugnant as such).

But this was perhaps not how we thought of the world with very low welfare when we looked at the figure above. We may have thought of it as a world with people who, at each moment, suffered terribly. And in this instantiation of the very repugnant conclusion it may seem repugnant. We may feel that intense unhappiness at a moment is difficult morally to balance with positive happiness.

Now this concern for suffering at a moment has nothing to do with the (very) repugnant conclusion as such and the same is true, as we noted, of Parfit's perfectionist concern. In both cases, if we want to cater to intuitions in relation to the examples, we ought to focus on momentary happiness and momentary unhappiness respectively. And we seem to face two views here that are different but not obviously in conflict. According to perfectionism, some pleasures seem to count for more, morally speaking, than others; the ‘higher’ they are, the heavier they count. And a pleasure is ‘high’ to the extent that part of its causal origin is to be found in some proper contact with the right subject (good music, good food, good friends, and so forth). With the other view, about unhappiness (suffering), it is similarly but more simply claimed that the more intensely an individual suffers at a moment, the heavier this suffering should count in our moral calculus.

We could perhaps combine these ideas. Or, we could accept just one of them and reject the other. Or, finally, we could reject both of them.

Regardless of how finally we assess them, I think we had better – in order to give them their best shot – state them in a gradual rather than a lexical manner.

Parfit realised this but thought that, unless one adopts a lexical view, it is impossible to avoid the repugnant conclusion:

If we merely compare Mozart and muzak, these two may also seem to be in quite different categories. But there is a fairly smooth continuum between these two. Though Haydn is not as good as Mozart, he is very good. And there is other music which is not far below Haydn's, other music not far below this, and so on. Similar claims apply to the other best experiences, activities, and personal relationships, and to the other things which give most to the value of life. Most of these things are on fairly smooth continua, ranging from the best to the least good. Since this is so, it may be hard to defend the view that what is best has more value – or does more to make the outcome better – than any amount of what is nearly as good. This view conflicts with the preferences that most of us would have about our own futures. But, unless we can defend this view, any loss of quality could be outweighed by a sufficient gain in the quantity of lesser goods.Footnote 19

He is right, of course, that unless we adopt the higher value view in a lexical manner, we cannot avoid the repugnant conclusion. But we have seen that there is no need to try to avoid it, since it is not repugnant as such. Even Parfit himself has come close to noticing this. So, if we think there is something to the objection from higher values, we had better factor them into our moral equation in a gradual manner. We then have to accept the repugnant conclusion, but we can still cater to what we find reasonable in the objection from higher values.

On this understanding of the perfectionist objection to total hedonistic utilitarianism presupposing that some pleasures are higher than others, we have indeed to accept that in some instantiations the Z world is better than the A world, but in order to reach this conclusion we must (on perfectionism) take into account the putative fact that higher pleasures (typical of ordinary people) carry a heavier moral weight than lower ones (typical of whales, infants and mentally disabled people), and we must acknowledge that it takes a lot of pleasure to compensate for intense suffering. In a perverse way these views may come to cancel out one another in some applications.Footnote 20 Very high pleasures can perhaps balance very severe pains, in a manner that strikes a hard-nosed utilitarian like the present author as quite right. It is in these instances as though both happiness and unhappiness had regained their nominal moral values.

In a similar vein, total theories like prioritarianism, if we apply them to problems in population ethics, can handle what has been called the ‘reverse’ repugnant conclusion,Footnote 21 where many people with small suffering, in a B world, can outweigh severe suffering among fewer people, in an A world. The prioritarian needs to admit that this is an implication of her view, but can be consoled by an observation made by Nils Holtug:

After all, it will take more individuals in B to render this outcome worse than A according to prioritarianism.Footnote 22

On such an understanding, we can fit into total views everything we find worthy of our concern about higher and lower pleasures at a time as well as the special significance of instances of extreme suffering. Each of these total views, amended in different ways, as well as utilitarianism, not only imply various different versions of the repugnant conclusion, they all offer putative (but mutually inconsistent) moral explanations of its truth.

8. Conclusion

The abstract intuition that the Z world is worse than the A world goes away when exposed to various debunking strategies. In particular, it has surfaced in the present context, that in some instantiations of the repugnant conclusion what is at stake is not the conclusion as such, but a special concern for higher values and/or severe suffering (at a time). I am not sure that these intuitions, about higher values and the special importance of extreme suffering, stand up to scrutiny. In particular, it is of note that many have thought (prioritarians) that lesser pleasures carry a heavier weight than more intense (higher) ones. Here it is obvious that there is a tension in Parfit's thinking; his lexical idea of superior values sits ill with his gradual prioritarian thought expressed elsewhere to the effect that the moral value of a benefit is less the better off, absolutely speaking, the individual being benefited is when receiving it.Footnote 23

Here it should suffice to note that the repugnant conclusion, in some form or another, is probably true. Hence, ‘the repugnant conclusion’ is clearly a misnomer.Footnote 24