1. Introduction

It's 2020. All festivals are being cancelled, and you haven't been to a party in months. Tonight there will finally be a party. You know that if enough people are going, the virus will spread among everyone, and even though you are healthy and will not end up in the hospital, enough others will, and cause the health care system to collapse (with many ensuing harms, not only to covid patients but also to other patients who will receive less attention, health care workers who have to work overtime, and all those who will suffer from further lockdowns).

Is it morally problematic for you to join the party? If parties are not your thing, think of something else that you really miss doing in times of lockdown (joining political or religious events, offline classes and meetings, and so on). As large gatherings are prohibited until there is a vaccine (and indeed herd immunity), in many countries it is illegal to do these things, but the question applies even if it were not illegal.

This is a collective action problem. The virus can only spread if a certain number of agents come together, and you cannot spread the virus and let the health care system collapse all by yourself.Footnote 1 When it comes to such problems, Parfit (Reference Parfit1984: ch. 3) and subsequent participation proponents say: there are participation-based reasons not to join the party, and hence it is morally problematic to join in light of these reasons. For, if you join the party, you will become part of the group of people who together spread the virus and, as a result, cause the system to crash.

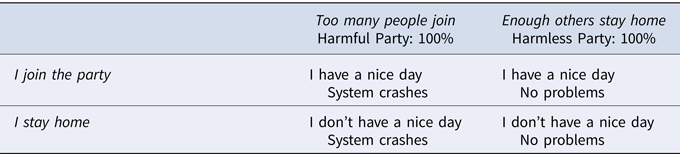

Contrast the following versions of the case:

Harmful Party

Everyone is going. It's so crowded that it is clear the virus will spread freely, and that the health care system will not be able to handle the number of patients.

Harmless Party

Apart from your friends, enough others decide to stay home. There is more than sufficient space for social distancing, the virus doesn't stand a chance, and there is no risk that too many people will end up in the hospital.

Risky Party

Many people are joining the party, though it is not yet clear whether there will be too many people, and whether the virus will be able to spread.

The claim of this article is twofold: firstly, participation-based reasons come in degrees, and, secondly, there are strong participation-based reasons to avoid Harmful Party. This latter claim will contradict prominent alternative views by Shelly Kagan and Julia Nefsky according to which there is no reason to avoid Harmful Party (as we will see).

The plan is this. In §2, I will examine the three cases more carefully. In §3, I will defend the idea that participation-based reasons come in degrees. In §4, I will discuss the difference between the accounts by Kagan and Nefsky. In §5, I will offer a justification for why certain participation-based reasons are stronger than others. In §6, I will defend my account against potential objections. In §7, I will conclude.

Note that following Nefsky (Reference Nefsky2017: 2744–45), I talk about reasons for actions rather than (for example) their wrongmaking features, or about moral responsibility for collective harms (as some authors do). I will push the idea that, in certain contexts (to be specified), participation-based reasons possess weight (i.e. alongside other kinds of reasons).

2. Kinds of groups

It will be instructive to have another case, an analogy, on the table:Footnote 2

Suppose there is a town at the bottom of a cliff. You and thousands of others are at the top, next to an unfortunately placed boulder. It blocks the sunlight of a third party, who offers you money to help push. You know that if enough of you push the boulder, the people at the bottom will die. You push the boulder and get your money. The crowd dies.

As in the party case, there are three versions of this situation. One is where enough people are already pushing the boulder to kill the crowd. One is where the group won't be big enough to move the boulder. And one is where it is still unclear if the group is big enough.

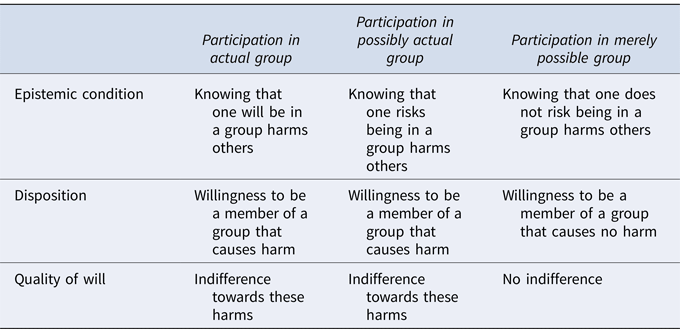

What's the difference between these three versions, more precisely? In Harmful Party there is an actual group of agents who together cause harm. In Risky Party, it is possible that there will be such a group. “Possibility” here, is to be taken epistemically: at the time of acting, such a group could be formed insofar as the agent can reasonably see. This could mean that the party has not yet begun, and you cannot tell how the day will unfold and how many people will come. It could also mean the party has already started and that there are quite a few people, but that you cannot determine, to the best of your knowledge (and to the knowledge of the virologists at the party), whether it is safe or too crowded. (So, here, it could be that it is in fact safe, or in fact unsafe, but there is not enough information to determine which.)

In Harmless Party, in contrast, it is clear that it is safe. Only a few people got tickets, and there is plenty of space. There is no risk that the virus will spread. In these kinds of cases, I will say that the group (of agents who together cause harm) is “merely” possible, or possible in a counterfactual sense. They would have caused harm if enough others had joined (which is not actually the case).

Thus, there are three kinds of groups: an actual group that causes harm, a possibly actual group (one that may be big enough in the actual future, namely when enough people join), and a merely possible group (one that will not be big enough).Footnote 3

In Wieland and Van Oeveren (Reference Wieland and Van Oeveren2020), we admit that you may have expected utility-based reasons to join cases like Harmful Party or Harmless Party (and possibly Risky Party, as I will discuss later). After all, you make no difference for the worse (the harm is already on its way, or it is not), and yet you could make a difference for the better – that is, for yourself. You will enjoy the party, and the harms (if any) remain the same. Yet, despite these considerations, we claimed there is still a serious participation-based reason against joining. Moreover, we suggested that it is the same reason, with the same strength, in all three cases.

Why did we think this? In all three cases, you are contributing something which is such that problems ensue because enough others also contribute. More specifically, we defined group membership in terms of “adding to an underlying dimension.”Footnote 4 For example, you belong to the group of agents that together kill the crowd when you (i) contribute to the amount of force exerted on the boulder, and (ii) the crowd is killed because enough others make this contribution. Furthermore, given that this contribution is the same in all three cases, we claimed that the reason not to participate deriving from it must be the same too:

We do not assume that it is worse to participate in actual groups that cause harm than to participate in merely possible groups, or that it is worse to participate in possible groups that might still become actual than to participate in groups that might not … For, in all these cases, one participates in these various groups so long as one adds to the underlying dimension … This contribution is always actual, and this is what constitutes, we take it, the same participation-based reason to refrain from [joining] in all three scenarios. (Wieland and Van Oeveren Reference Wieland and Van Oeveren2020: 181)

For example, participation-based reasons not to eat meat would not come in degrees, and you have the same participation-based reason irrespective of how others happen to act. According to this view, it does not matter if the group of consumers is already big enough to incentivize more production (and so more animal suffering), or if it will not be big enough, or if it is still open whether it will be big enough.Footnote 5

Yet, being a participant and having reasons not to be one are, in principle, two separate issues. I think that participation proponents can still explain why participation-based reasons can – and, indeed, should – come in different degrees.

3. Why degrees?

Consider:

Counterfactual Party

You know that everyone will stay home, and that you will be the only partygoer.Footnote 6

One would think that it is totally fine to join this party (which is merely counterfactual: a party that would have existed, if others had acted differently). Even so, it still holds that you are doing something which is such that, if enough others participate, problems would ensue. Or, in terms of contribution, you are contributing a human being to some limited space which is such that the virus can spread if enough people do so as well. Thus taken, it seems to follow from our account that there are reasons not to join Counterfactual Party, and the same goes for other accounts that want to remain insensitive to the conduct of other agents. But that seems implausible. There are no reasons to avoid merely counterfactual parties.

I see at least three options for participation proponents: (i) argue that there are no participation-based reasons to avoid merely counterfactual parties because there are only reasons to avoid actual parties, (ii) bite the bullet and maintain that there are participation-based reasons to avoid merely counterfactual parties; or (iii) argue that participation-based reasons come in degrees, and that there are no participation-based reasons to avoid merely counterfactual parties. Next, I will defend (iii) against (i) and (ii).

Let us assume, for a moment, that there is a threshold for the health care system to crash. This threshold is the number of party people – n – needed to spread the virus and to make a sufficient number of people sick, and this number of sick people is just larger than the amount the system can handle. If, but only if, n or more join, the system will collapse.

One option for participation proponents would be to say – response (i) – that you only have participation-based reasons to avoid the party if you know that the number of people actually at the party is n−1 or higher (the threshold minus you). For example, if the threshold lies at 100 party people, and you know this, then you will have a participation-based reason to avoid the party when there are already 99 others at the party (or more).

The advantage of this approach is that it does not generate reasons to avoid merely counterfactual parties. Even so, it fails to account for Risky Party. Many people are joining this party, though it is not yet clear if there will be too many people, and whether the virus can spread. So the threshold is not yet met, but people might still enter and the threshold might be crossed later. Should we think that, in such a case, you have no participation-based reason to stay home, not even a moderate one?

Here's one way to think about this. As soon as number 99 enters, you will have a participation-based reason to leave the party. It is practically impossible to count visitors at a public party, though one could imagine that the organizers display a huge sign with the actual number of visitors. But when it goes to “99”, who should leave the party? In such a situation, then, all the visitors will have a participation-based reason to leave. But as soon as someone acts in light of this reason and actually leaves, the participation-based reason to leave disappears for the others, who can then stay.

Apart from these complications, though, it is not very plausible that such cases have sharp thresholds.Footnote 7 Presumably, there is a number of people (say 50) at which we can say that the party is safe (or at least that the hospitals can still help everyone in an adequate way), a number of people at which we can say that the party is unsafe (say 150), and a grey area in between where the health care system becomes more and more stretched and where it is unclear whether it can still handle the number of patients. In this area, I would still say that there are still participation-based reasons not to go (even though they are not as strong as when you know that it is unsafe).

Response (ii) would be to say that there are participation-based reasons to stay home when there are zero party people (in the merely counterfactual party), just as there are reasons to stay home when there are 49 party people (or any number below and above the threshold).

This response is problematic too. Suppose the party is cancelled, and there is a stack of face masks at the party place from which numerous people can benefit. So, there are strong reasons to go to the party place and get these masks. Assume for reductio that there are participation-based reasons to avoid merely counterfactual parties. In that case, there would be participation-based reasons not to get the masks. But, of course, these reasons are easily overridden in this case. It is more important to help others than to avoid participation in a party that does not exist. But, if participation-based reasons are easily overridden here, then – unless we get a story on the difference – they will be overridden in the other cases too.

Consider the version of the cliff analogy where the group is already big enough to move the boulder and kill the crowd. In this case, there will be participation-based reasons to join the group (namely, to benefit the third party and allow them to enjoy the sunlight), and there will be expected utility-based reasons to join (namely, you will get money and make no difference for the worse). If anything, there should also be strong participation-based reasons against joining this group. For, by joining you will be one of those who kill the crowd. However, if participation-based reasons are maximally weak in the face masks case, then why are they not maximally weak here as well, and thus easily overridden by the reasons in favour of pushing? If, generally, participation-based reasons are easily overridden by other kinds of reasons, then that would deflate the whole participation account. Hence, we should want more: an account of degrees.

Here is my proposal – response (iii):

Participation-Based Degrees

The more likely it is that the group will cause harm, the stronger the participation-based reason not to join this group.Footnote 8

This account yields the strongest participation-based reasons not to push in the cliff analogy when the group is already big enough to move the boulder. For, in such a case, it is certain that the crowd will be killed. It is also supposed to yield no participation-based reasons to avoid merely counterfactual groups (as in Counterfactual Party). For, in such cases, it is certain that no harm will ensue. Participation-Based Degrees may appear intuitive at first sight. Even so, my aims in the rest of the article will be, firstly, to show that it differs substantially from alternative views in the literature (if you are already convinced of this, you may skip to §5), and, secondly, to provide a justification. Indeed, why think that the strength of reasons – particularly participation-based reasons – covaries with the likelihood of harm?

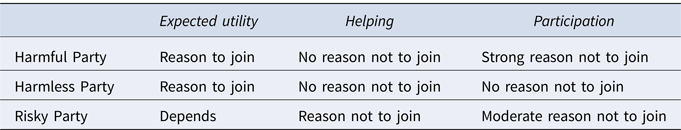

4. Alternative views

To see more clearly what Participation-Based Degrees proposes, it will be instructive to contrast it with prominent non-participation accounts – Kagan's expected utility account and Nefsky's helping-based account – which I will address in turn.Footnote 9

In Harmful Party, you might think: why not join too since disaster is already on its way and I might as well enjoy the party? Indeed, if you know that too many others are joining already (causing the health care system to crash), then the only difference between you joining too and you staying at home will be whether you have a nice day or not. Similarly, in Harmless Party, if you know that the threshold will never be met, again the only difference will be whether you have a nice day or not.

In such calculations, one needs to make assumptions. First, it is assumed in Harmful Party that you are sure that you yourself won't suffer from the virus (though you could assign some probability to this as well). Further, I am excluding any potential “moral” costs, such as participation costs in Harmful Party (where you may feel bad about your participation) or fairness costs in Harmless Party (where you may feel bad about having a great time, while others are bored at home). But irrespective of such details, there could well be expected utility-based reasons to participate in groups of agents that together cause harm.

Could there also be expected utility-based reasons against joining such groups? As Kagan (Reference Kagan2011) argues, there could be such reasons so long as there is a chance that you make a difference to the harm caused by the group, i.e. the chance that you together with others exactly hit the threshold. Suppose, again, that there is a sharp threshold: exactly 100 party people are needed to cause the health care system to crash. If it is still open whether there will be exactly 99 others, and that you can make a difference between causing the system to crash and preventing it from crashing, it may well be that you shouldn't run this risk (depending on the numbers). In such cases, there can be expected utility-based reasons not to join.

In all other cases, where there is no risk that you make a difference, as in Harmful Party or Harmless Party, or where there is no such sharp threshold, or where there is such a sharp threshold, and it is still open whether it will be met, but it is not likely enough that you will make a difference to it, there are no such reasons.Footnote 10

According to Nefsky's proposal, you may have reason to help bring about some good outcome even in some of the latter cases. For example, you have helping-based reasons not to party and even to help prevent the virus outbreak in all Risky Party-type of cases, when it is still possible that the outbreak can be prevented.Footnote 11

Moreover, Nefsky suggests that such reasons come in degrees: “If Y [some good outcome, such as preventing the virus outbreak] is unlikely, one can still satisfy the conditions for helping; one's reason to act might just not be as strong as it is in a case in which the chances of Y are closer to 50–50” (2017: 2763). Thus, if the chance of the good outcome is 50%, and it is fully up in the air whether it will be realized, you have a strong helping-based reason to join the group that tries to bring it about. If the good outcome gets more likely or more unlikely, these reasons get weaker. They fully disappear, if the outcome is no longer possible, or if it is already certain. This implies that there are no helping-based reasons in Harmful Party and Harmless Party. In Harmful Party, you cannot help bring about a good outcome when you already know that it will not come about. In Harmless Party, you cannot help bring about a good outcome when you already know that it will come about already, without your help.

Taken together, these reasons are very different from my participation-based reasons. In Harmful Party (where the outbreak is certain), there is an expected utility-based reason to join, and no helping-based reasons to try to prevent it, while, according to my proposal, there is a strong participation-based reason not to join this group. In Harmless Party (where there will be no outbreak), there is an expected utility-based reason to join, no helping-based reasons to prevent anything, and, according to my proposal, no participation-based reason not to join this group.Footnote 12 In Risky Party (where it is still up in the air what will happen), there could be expected utility-based reasons not to join, there is a helping-based reason to try to prevent the party, and, I say, a moderate participation-based reason not to join the party.

This is, to be sure, only an outline of how these kinds of reasons can be stronger or weaker, and how these degrees can be made more precise is something we will not take up here. Instead, my task will be to defend Participation-Based Degrees. The central question is why participation-based reasons should come in the degrees described here.

5. Justification

So, why is it worse to participate in actual groups that cause harm than to participate in possible such groups? Taking my cue from suggestions by Christopher Kutz and Julia Driver, my answer will basically be that the former displays a greater degree of indifference towards the harms caused by these groups.

Driver compares two agents, Aubrey and Blake, who find themselves in a Harmful Party-type of case where there are already enough consumers buying meat to sustain factory farming, and the question is whether they may join this group. While Aubrey refuses to do so because of participation-based reasons, Blake decides to eat meat because she thinks that participation-based reasons have no weight. What can we say against Blake? Here is Driver's suggestion: What makes that participation morally problematic, in her case, is that the eating of meat displays a willingness to cooperate with the producers of a product that is produced via huge amounts of pain and suffering. (2015a: 79) So, in terms of Harmful Party, what makes joining the party problematic is that it displays a willingness to cooperate with the organizers to make the party a success, and, as a result, spread the virus. But you should not display such willingness, and that is why you have a participation-based reason not to join. Next, I will explore Driver's suggestion further (and make it gradual). Indeed, what is this attitude of “willingness”, and how is it displayed by agents like Blake?

The view is not that joining a party displays some message, indirectly, through certain contingent conventions (cf. also Nefsky Reference Nefsky2018: 282). Holding a white flag, for example, receives its meaning in such an indirect way. Doing so during a war or during a protest mean different things, and in yet further contexts there might be no convention that connects a white flag to any meaning. Similarly, joining a party in times of corona is sometimes taken to express that you do not agree with the interventions put in place by the government, and how they restrict various freedoms. However, there are no universally held conventions that connect parties to statements that you are willing to cooperate with others to spread the virus. And yet, following Driver's proposal, that is the message that is displayed.

Instead, I take it that your participation gains expressive significance in virtue of something about you. Here is Kutz: The basis of accountability is the content of an individual's will and not the particular causal contribution. Although, in fact, no individual bomber made a difference to the death and suffering that all produced, … the will of each was manifested in the acts of all. (2000: 141–42, emphasis added)

The question, as before, is what this manifestation precisely amounts to. Here's a first idea:Footnote 13

(D-1) S displays a problematic attitude towards harm H if: S acts with an intention to do her part in causing H.

In the cliff analogy, then, you would display a problematic attitude only when you act with an intention to do your part in killing the crowd. Clearly, you do not act with this intention. You just want the money, and push the boulder for this reason. The harm done is an unintended side effect of a group of individuals pursuing small personal benefits. Given cases like these, Kutz (Reference Kutz2000: e.g. 143, 162) suggests the following variant:

(D-2) S displays a problematic attitude towards H if: S acts with an intention to do her part in project X, and X causes H.

According to this, it's not needed that you endorse the harm. It's merely required that you act with an intention to do your part in the boulder project (and, secondly, that the project in fact causes harm). But, it's not even clear that you act with this intention. Again, you just want the money, and could not care less about any joint project (e.g. if others join you in pushing, or if the third party gets to see the sunlight). Given (so-called “unstructured”) cases like these, Kutz (Reference Kutz2000: 186ff.) proposes the following variant:Footnote 14

(D-3) S displays a problematic attitude towards H if: S participates in a way of life that causes H.

In this case, it does not matter whether you want to do your part, or act together with others in some project. It is merely required that you participate in a “way of life”, namely “a background of independent activity and shared values” (Kutz Reference Kutz2000: 186). In the cliff analogy, this way of life is pushing the boulder for money, and neglecting the lives of the crowd at the bottom. In the party case, this way of life is enjoying the party, and neglecting those who suffer from an outbreak. I think this is on the right track, although I propose to add an explicit epistemic condition (also considered by Kutz Reference Kutz2000: 155ff.):

(D-4) S displays a problematic attitude towards H if: S knowingly participates in a way of life that causes H.

According to this account, it matters whether you are aware of the crowd at the bottom, and that they will be killed if enough others push too. If you are not aware of this, and you could not have known better even if you cared and were attentive enough, then it does not seem plausible to think that you display any problematic attitude. Thus, the idea is that you display certain attitudes in virtue of your epistemic condition.Footnote 15

Next, I will zoom in on the exact content of these attitudes, and suggest that they differ in our three types of cases (and yielding Participation-Based Degrees).

When you join Harmful Party, you know you are joining a group that will cause harm. By doing this, you don't distance yourself from its members and the harm they cause. That is, you become one of the people who caused the health care system to collapse. What does this say about you? It says that you are willing to be a person who together with others causes harm. In this way, you display indifference.Footnote 16

When you join Risky Party, you know you are joining a group that risks causing harm. By doing this, you don't distance yourself from its members and the harm they risk. You will become one of the people who risked the lives of others. This says that, to some extent, you are still prepared to be a member of a group that causes harm. Importantly, such a disposition may come in a greater or lesser degree. For example, when the threshold lies at 100 (as before), you might want to give it a try when you already see 50 others at the party, but not when you see 90. Generally, the greater the likeliness that the group will cause harm, the more you are prepared to belong to a group that causes harm if you decide to join them, and, consequently, the more indifference you display towards the corresponding harms (that might occur).

When you join Harmless Party, things are quite different. You know you are joining a group that is not risking any harm. By doing this, you only participate in a group that will not cause harm, and so will not become one of the people who risked the lives of others. What does this say about you? It merely says that you are willing to be a member of a group that causes no harm. You don't display indifference.

Thus, I propose the following justification of Participation-Based Degrees: the more likely it is that the threshold will be reached, the greater your willingness to be a member of a group that causes harm, and the greater the lack of concern you display for the harm. As the latter is morally problematic, you have a strong participation-based reason to avoid Harmful Party, a moderate (i.e. moderately strong to weak) participation-based reason to avoid Risky Party, and no participation-based reason to avoid Harmless Party (or, indeed, Counterfactual Party).Footnote 17

6. Discussion

Next, I will respond to a series of eight related worries about this justification of Participation-Based Degrees.Footnote 18

Worry (1): “When many people are already pushing, and the group is big enough to move the boulder and kill the crowd, my particular contribution will be superfluous and won't cause any additional harm. Hence, it does not display any indifference.”

Response: Even when your participation will not make a difference to the outcome, it will still make a difference to the group you belong to. Do you belong to those who knowingly kill the crowd? If so, you display indifference towards them. In response, you cannot defend yourself by saying that, since your participation is superfluous, you do not belong to that group. For, as per assumption, you already count as a participant (see §2), and the question addressed in this article is what's problematic about that.

Even so, inspired by the accounts by Kagan and Nefsky, you might want to defend yourself by saying that your contribution does not display any indifference because doing so does not risk making a difference to the outcome, or because you can no longer help to prevent it. Indeed, you might ask “why do I display indifference when I know that the harm will result whether I push or not?” This is a fundamental worry. By pushing, we all agree, you belong to the group who killed the crowd. What we disagree about, however, is that such group membership matters. Who cares, one might think, what group you are in?

My story was this: you knowingly join a group that will cause harm and don't distance yourself from them or the harm they cause. This might not tell us that you are willing to risk making a difference to the harm, or that you do not want to help prevent it. Even so, it does tell us that you are willing to be a person who together with others kills the crowd (and more so than in other cases where it is less certain that the group will be big enough to move the boulder). I do not think that proponents of the views by Kagan and Nefsky can deny that you display this particular message.

What they can try to deny, of course, is that displaying such messages is morally problematic – which is a different point. I consider it horrific to display these messages. Moreover, I do not think that changing the message to “Yes, I am willing to be a person who together with others kills the crowd, but only when I know that the group is already big enough” makes it any less bad. Yet, I do not have more on offer to justify this position here.Footnote 19 If you agree with me that we should avoid displaying such messages, then my point is that you will have a stronger participation-based reason to avoid cases likes Harmful Party (because in that case you would display a stronger willingness to participate in a group that causes harm) than to avoid the other parties discussed (where you would display such willingness to a lesser degree).

Worry (2): Consider the following variant of the cliff analogy:

Everything is the same as in the original story, but now the third party has a Plan B. If not enough people join to move the boulder, then they will stand up from their chairs, send away all the helpers without any pay, and move the boulder themselves.

In this case, it is certain that the crowd will die. If we now say that, in this case, there are still participation-based reasons not to push for money, then, it seems, we are not so much concerned with the outcome (the lives of the crowd), but merely with “keeping one's hands clean”.

Response: In principle, it is open whether there are participation-based reasons in these kinds of cases. Insofar as Participation-Based Degrees is concerned, there are participation-based reasons not to join to the extent that it is likely that the group will cause harm. But, the case description says nothing about this. It merely says that it is certain that the third party will cause harm, all by itself, if there will not be enough helpers.

As a variant of the case, imagine that the third party does not send you away, but instead joins the group in pushing. Here, you do seem to have a participation-based reason to stop pushing. In such a case, it is right that the reason to stop is about not belonging to certain groups. By stopping, you avoid membership of the group that kills the crowd at the bottom. You are no longer one of them. In this sense, you will keep your own hands clean.

Even so, the account is not simply about keeping your own hands clean, for two reasons. First, for all I have said, there might not only be participation-based reasons to stop pushing yourself, but also participation-based reasons to prevent others from pushing for money, namely to avoid belonging to the group that failed to save the crowd. Second, and crucially, my view is not only about avoiding personal identification with certain groups, but also about not displaying indifference towards the given outcomes of concern. Membership is problematic because these outcomes are problematic, and that's why you should not relate to them in a problematic way.

Worry (3): Suppose you are like Blake and respond in Harmful Party: “I truly care about those harms! But, the health care system is going to collapse anyway, so I might as well join the party.”

Response: This view is not about your reflective endorsements. You may think you care about the harms, but by becoming a member of such a group, you display something else.

Also, I am not denying that you also have an expected utility-based reason to join. It is just that you have a substantive participation-based reason not to do so. Or again: it is morally problematic for you to join, and that is because of participation-based considerations.Footnote 20

Consider the following variant: “I truly care about those harms! That's why I didn't go to the party when it was still open whether the harms would result. But, only as soon as I saw (on a livestream of the party, say) that disaster was already on its way, I decided to go.” So, the suggestion would be that, if this is your reasoning, you need not display indifference in Harmful Party (and that joining Risky Party might well be worse than joining Harmful Party). My response, however, remains the same: in such a case, you are running expected utility-based reasoning, but neglect concerns about participation.

Worry (4): “I did think about the crowd at the bottom, and I care about them and normally would never have pushed for money, but I really need the money to save the lives of 10 others.”

Response: In this case, it is plausible to assume that the expected utility-based reason to save the lives of the 10 outweighs the participation-based reason not to push for money. (To be sure, I did not present any account to weigh such reasons, but getting the money to save 10 people will likely suffice, while getting the money for, say, an ordinary drink for yourself will not.) I agree that, in selected cases, there could be a justification for your participation, and that if your justification is good enough, you need not be displaying indifference.

My preferred analysis of such cases is that, even when you do not display indifference in such cases, you still knowingly participate in a collective harm. Specifically, you believe that H is bad, and that you are joining a group that you should otherwise not participate in, and would rather distance yourself from. This is not indifference on your part, but it is still a mental state of yours that renders your participation morally problematic to some degree (i.e. even if it does not render it all-things-considered wrong).

One further way to think about this would be to say that participation-based reasons have a default weight, just as rules of thumb (e.g. “adhere to covid measures”) have default weight for act consequentialists. Such rules are rough, pre-reflective generalizations of what to do, but, as per concerns about rule worshipping, they do not justify any particular course of action. Participation-based reasons, then, have a default weight stronger than any benefits participation may bring, though this weight may be defeated, in selected cases, after further reflection.Footnote 21 What does it take, exactly, to render joining some group (that harms or risks harming others) justified? This is a difficult issue that all accounts in the debate face. It remains to be seen how and when moral considerations of participation, helping, fairness, or other, can be overruled by the benefits that participation may bring.

Worry (5): “Just a minute ago I didn't know about the crowd at the bottom, and now that you informed me, my participation suddenly becomes problematic!”

Response: This is a consequence of the view. If you push for money and you could not have known about the crowd at the bottom, you do not display anything. But, as soon as you get updated about this and hear that they will be killed, and yet you decide to continue to push for money, you start displaying indifference towards the crowd (which, in turn, makes your participation problematic).

Worry (6): “People know I don't like parties. If I don't go, it is implausible that I thereby display adequate concern.”

Response: Displaying concern is indeed tricky. Just as I might not go to parties for various reasons, I might decide not to push for various reasons, or even organize protests for the wrong reasons (e.g. I want to impress someone and couldn't care less about the crowd at the bottom).

Even so, the view is not that you have participation-based reasons not to go because you should display concern for the given harms.Footnote 22 Instead, the view is that you have such reasons because you should avoid displaying a lack of concern, and you can establish this only by avoiding membership of the relevant groups.

Worry (7): “In contrast to what you say, it is still problematic to join Harmless Party (where you know it is safe). For one, others (e.g. health care workers) might still interpret my action as one of indifference. For another, going to parties when it is safe might create a disposition to go to parties in other circumstances too.”Footnote 23

Response: For just these reasons, I am open to the idea that there are weak participation-based reasons in Harmless Party-type of cases (where the group is too small to cause any harm). Joining these might not be as problematic as in the other cases, but there could still be a participation-based reason not to go that has some weight.

However, they still disappear when any such considerations do not apply. There might well be cases where it is clear to everyone that the situation is safe, and that you are merely joining a group that is not risking any harm, and where you yourself are able to keep it separate from situations where it is unclear if it is safe (or clear that it is unsafe). Moreover, even when it is really hard to see if it is safe, and you can't tell, you are just in a Risky Party-type of case (rather than Harmless Party), where it is still open what will happen. In such a case, I argued, you have a moderate participation-based reason not to join.

Worry (8): “If I join the protest, I am one of those who caused the health care system to collapse. But, if I stay home, I am one of those who didn't speak out against racism!”

Response: I do not deny that there are cases (many cases, perhaps) where you have participation-based reasons to do opposing things. A straightforward approach to resolve such dilemmas would be to look not only at the likeliness of the harm – the main claim of this paper – but also at, for example, the gravity of the harm (cf. Lepora and Goodin Reference Lepora and Goodin2013: 103, Barry and Øverland Reference Barry and Øverland2016: 237, and Talbot Reference Talbot2018: 2250ff.). This brings me to the conclusion.

7. Conclusion

Parfit and subsequent participation proponents say: there are participation-based reasons not to join collective harms. In this article, I asked: why is it actually problematic to participate in such harms (given that your participation makes no difference to the latter)? Following suggestions by Driver and Kutz, I offered a justification in terms of the agent's quality of will: you should not participate in collective harms because doing so would display a lack of concern for these harms. Moreover, I have argued for a gradual account – Participation-Based Degrees – according to which the more likely it is that the group causes harm, the greater the lack of concern you would display for the harm, and the stronger your reason not to participate.

In closing, I should like to point out that my account differs from other participation-based accounts, and will show this for two prominent examples. Firstly, Barry and Øverland imagine the following case:

Tom's disposing of his waste makes no apparent difference to the drowning of Robinson. Fifty others shovel waste into the lake and that number, or less than that number, is enough to drown Robinson. If Tom were to have abstained, the island would still have been flooded, and Robinson would still have drowned. (2016: 226)

This is a Harmful Party-type of case, where the group is already big enough to cause harm. As in Harmful Party, the harm has not yet been done. At the time of acting, the health care system hasn't yet crashed, just as the island has not yet been flooded. But, one knows that enough agents are gathering already to bring about these outcomes, and one can decide to join them or not.

Suppose the threshold lies at 40 waste throwers needed to cause Robinson to drown, while 50 others are disposing of their waste already. If Tom joins this group, then according to Barry and Øverland (Reference Barry and Øverland2016: 238), there is a 40/51 chance that he is in the actual group that kills Robinson. This chance increases if the group of waste throwers is smaller (e.g. if there are 43 others, his chance of being in the actual group is 40/44). Generally, their proposal is that the strength of the participation-based reason (or “overdetermination-constraint”) for Tom not to dispose of his waste depends on this chance. That is, the more likely it is that he is in the actual group that causes harm, the stronger the participation-based reason against joining.

This account goes in my direction, but is distinct. According to Participation-Based Degrees, Tom's participation-based reason against joining is maximally strong if the group is big enough to kill Robinson. If the threshold lies at 40, it does not matter, according to my view, if there are 45 or 87 other waste throwers. What matters, instead, is the probability that the group will be big enough. According to Participation-Based Degrees, Tom's participation-based reason against joining remains the same if it is certain the threshold will be crossed, but it gets weaker when it gets less likely that the threshold will be crossed. For example, if there seem to be only 33 waste throwers, and it is unlikely that the threshold of 40 will be crossed, Tom's participation-based reason against joining is weaker than when there are already, say, 38 waste throwers. Or so I argued in §§5–6.

My account also differs from the account by Lepora and Goodin (Reference Lepora and Goodin2013: esp. 65–66) who suggested that the more likely it is that you make a difference to the harm, and so the more “central” you are to it, the stronger the participation-based reason not to join. For example, the organizers of the party are more central to the harm compared to the visitors, and so, by this account, the former have a stronger participation-based reason not to organize the party.

I consider it plausible that, to some extent, how central you are to the harm matters, though think it should be supplemented with my Participation-Based Degrees.Footnote 24 For, without the latter, Lepora and Goodin's account implies that if there is zero chance that you make a difference to the harm – which may well apply in numerous collective action cases – then there is at most a very weak participation-based reason not to join. But, as I argued, there could be very strong such reasons (as in Harmful Party, where the harm is certain, and there is no possible future path where you make a difference to it).

This invites tricky follow-up questions about aggregation. Contrast:

(A) You display a great deal of indifference towards the crowd at the bottom (as there is a high chance that there will be enough people to move the boulder), but your contribution is only marginal, i.e. you do not exert a lot of force on the boulder.

(B) You display a low degree of indifference towards the crowd at the bottom (since there is only a tiny chance that there will be enough people to move the boulder), but you exert a lot of force on the boulder and your contribution is considerable.

Which of these is worse? One option would be to give expressive and instrumental factors equal weight, and then (A) and (B) may be equally problematic. Another option would be to weigh them differently, and, again, there are various ways to do this. In this article, I can stay neutral about these possibilities. What matters, here, is that the expressive component (as identified in this articleFootnote 25) has at least some moral weight, and that joining Harmful Party is at least somewhat morally problematic – and indeed more so than joining the other parties.Footnote 26

Competing interests

The author declares none