1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (WHC)Footnote 1 and its World Heritage sites have received scholarly attention from a variety of disciplines.Footnote 2 While this literature is considerable, the composition and the development of the List of World Heritage in Danger (IDL) has received less academic attention. The major aim of this article is to develop a deeper understanding of the function and use of the IDL within the context of transnational environmental regulation. The article provides a comprehensive empirical analysis of the IDL based on official statutory records on the IDL from 1978 to 2017, which were processed through several cycles of coding to generate quantitative data. The patterns emerging from the analysis are discussed in relation to the emerging literature on the WHC and the IDL. Both the literature and the analysis indicate that the IDL serves something of a dual purpose in regulation. Firstly, it can operate as a ‘fire alarm’, which alerts the international community and fosters cooperation around at-risk sites; secondly, it can be used as a disciplinary instrument to ‘name and shame’ states. Thus, these findings have relevance for how we might conceive and apply non-compliance procedures (NCPs) under transnational regulatory regimes.

Part 2 of the article provides a brief synopsis of the WHC, introducing the IDL and showcasing how the current literature portrays its use. Part 3 provides an explanation of the methodological approach to the data collection and analysis used by the authors. In Part 4 of the article, the results of the quantitative research are presented and discussed. Emerging patterns are noted, particularly across regions (Europe, Asia, Africa, etc.), and reasons are identified for the listings. Finally, in Part 5, the dual purpose of the IDL as a regulatory tool is discussed: firstly, as a fire alarm; secondly, as a reputational sanction (the naming and shaming aspect).

2. THE LIST OF WORLD HERITAGE IN DANGER (IDL)

In a little over 40 years, the WHC has become one of the most widely ratified instruments of international environmental and cultural heritage law. Today, the World Heritage List includes over 1,000 properties in nearly 170 countries and several hundred delegates attend the annual sessions of the WHC’s governing body, the World Heritage Committee (the Committee).Footnote 3 The states parties put forward World Heritage nominations and the Committee makes the decisions on whether to list, refer, defer, not to list and/or delete sites on the World Heritage List.

Pursuant to Article 11(4) WHC, the Committee can list a site as ‘In Danger’ and elect to place it on the IDL. While the mechanism for an IDL had been available under the original text of the WHC (and the first listing on the IDL took place in 1979), it was not until 1982 that the Committee requested the advisory bodiesFootnote 4 ‘to prepare draft guidelines on the criteria and procedures relating to the inclusion of a site on the List’.Footnote 5 Thereafter, in 1983, revisions to the ‘Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention’Footnote 6 (Operational Guidelines) were made, which included support for national safeguarding efforts and contributions to international fund-raising campaigns for at-risk sites.Footnote 7

The criteria and objectives for inclusion on the IDL have been amended multiple times and are currently found in paragraphs 178 to 182 of the Operational Guidelines. The ‘danger’ to a site may fall into one or either of two broad categories: (i) ‘ascertained danger’, where the site is faced with ‘specific and proven imminent danger’;Footnote 8 or (ii) ‘potential danger’, where the site is faced with ‘major threats which could have deleterious effects on its inherent characteristics’.Footnote 9 The Operational Guidelines give examples of each of these situations: for example, ‘a modification of the legal protective status of the area’, a ‘planned resettlement or development project’, or an ‘outbreak or threat of armed conflict’.Footnote 10

The fact that these activities are described as ‘examples’ suggests that the IDL is not exhaustive and leaves open the possibility that other activities may be included. Accordingly, the criteria in the Operational Guidelines leave substantial room for interpretation and provide the Committee with discretionary power to act as something of a regulatory gatekeeper.Footnote 11 On the recommendation of the advisory bodies, the Committee decides if a site meets the criteria for inclusion. Indeed, Battini and others argue that the management of the IDL has become one of the ‘principal powers’ of the Committee.Footnote 12 Moreover, while In Danger listings are not intended to be seen as a sanction, it is clear that both potential and actual listings have come to be associated with some degree of ‘naming and shaming’.Footnote 13 Consequently, the room for interpretation coupled with possible stigma create a context in which a potential listing can become an item of both action and negotiation. In short, the potential of inclusion on the IDL may push some states into action and lead them to request help as a means of avoiding listing.Footnote 14 Other states might delay action by entering into negotiations with the Committee and refusing to accept the proposed listing.Footnote 15

One of the consequences of the discretionary nature of the Committee’s determinations and the varying responses of states to the IDL is that the list seems to serve several purposes, of which two figure most clearly in the research. On the one hand, the IDL can function like a ‘fire alarm’, drawing attention to threats at World Heritage sites, and serve to elicit financial and practical help from the international community. The fire alarm mechanism gives the IDL positive connotations, appearing as a very practical, forward-looking and collaborative mechanism, which may help to build better conservation management and transnational relationships.Footnote 16 It can also bring ‘political benefits’ to states, providing them with a reason to obtain resources, for example, to conduct their own environmental impact assessments.Footnote 17 On the other hand, the IDL can function as a naming and shaming tool for states that fail to comply with the WHC. This naming and shaming approach contributes to a secondary function wherein the IDL serves as a disciplinary instrument or reputational sanction aimed at recalcitrant states.

States have directly challenged the naming and shaming (disciplinary) approach of the IDL on the basis of the principle of state sovereignty. Several states – including Australia, the United States (US), and Nepal – have argued that state consent is needed for formal inclusion of a site on the IDL.Footnote 18 However, after the contentious debates surrounding the potential In Danger listing of Kakadu National Park (Australia) in the late 1990s,Footnote 19 it has been settled by the Committee that there is generally no requirement for state consent.Footnote 20 This raises questions about what legal rights, from a procedural justice perspective, states have under the World Heritage regime. Litton, for example, suggests that states that oppose the inclusion of their sites on the IDL should at least be entitled to proper notice, an opportunity to be heard, and ideally ‘some form of review’.Footnote 21 These suggestions are broadly in line with the practice of global administrative law (GAL) in today’s transnational regulatory environment.Footnote 22 While no formal mechanism as suggested by Litton currently exists, it may be argued that the often long, drawn-out processes surrounding inclusion on the IDL, which usually include a preliminary or post Reactive Monitoring Mission (RMM), serve this purpose. RMMs are a part of the formal process for monitoring World Heritage properties under the Convention framework. The process is undertaken by visiting the site and state concerned in response to threats received by UNESCO or the Committee. More specifically, ‘reactive monitoring’ is defined as ‘the reporting by the Secretariat, other sectors of UNESCO and the Advisory Bodies to the Committee on the state of conservation of specific World Heritage properties that are under threat’.Footnote 23 According to the Operational Guidelines, the objective of RMMs is the ‘preservation’ of properties on the list as opposed to, for example, penalizing non-complying states.Footnote 24

To give more weight to these discussions and further interrogate how the IDL has functioned and currently operates, later sections provide an empirical analysis of the operation of the IDL from 1978 to 2017. Before presenting these findings, the methodological approach is described briefly.

3. METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH TO THE COMPILATION AND USE OF THE IDL

The methodological approach used in this article draws inspiration from earlier quantitative World Heritage studies which generated datasets by using a combination of readily available statistics and coding of statutory records.Footnote 25 We have used the World Heritage statistics on the IDLFootnote 26 as the starting point and have incorporated further information from the State of Conservation Reports and Reports of the Rapporteur of the World Heritage Committee sessions from 1978 to 2017.Footnote 27 The World Heritage statistics provide an overview of sites presently listed on the IDL covering the period 1978–2017. Sites which have lost their World Heritage status (i.e. have been delisted) are therefore excluded,Footnote 28 which brings the total number of listings on the IDL between 1978 and 2017 to 91. Out of these, only five sites have been listed on the IDL twice (see the Appendix to this article). In the analysis below we differentiate between the ‘historic IDL’, which includes the period 1978–2017, and the ‘current IDL’, which represents the list as of July 2017.Footnote 29 The reason for this distinction is to show the development of the IDL over time. It is noted that several sites have been added to the IDL but were then removed during the period 1978–2017. The current list, on the other hand, presents a snapshot of the compilation of the IDL. Both perspectives are interesting to consider.

To tackle the extensive material from the statutory records, we conducted targeted searches, followed by coding a combination of the decisions and background material provided for each decision leading to inclusion on the IDL. In the context of the IDL, this is exemplified by using the reasons for inscription on the IDL as a code.Footnote 30 The first coding cycle consisted of identifying the descriptive reasons (such as earthquakes or tornados) for including sites on the IDL. The second coding cycle started once all the descriptive reasons for listings had been compiled and consisted of developing fewer research-generated ‘threat categories’. These threat categories are broader units of analysis which capture the essence of the listings.Footnote 31 Drawing on the above examples, related codes such as earthquakes or tornados were conjoined into the broader category of ‘natural disasters’. In all, the following threat categories were developed (abbreviations refer to those used in the tables in this article):

(a) human-led development projects (DP), represented by, for example, the construction of dams, roads and other threatening infrastructure;

(b) management and legal issues (MLI), such as the absence of management plans or unclear legislation;

(c) war and civil unrest (WCU);

(d) natural disasters (ND), such as earthquakes, tornados and volcanic eruptions;

(e) environmental degradation (ED), which relates to the long-term destruction of habitats and species; and

(f) material conservation issues (MCI), which refers to the physical degradation of the material fabric of cultural sites.

While an attempt was made to locate a single reason for each listing, on multiple occasions there were in fact several interrelated reasons for inclusion on the IDL, which is indicated by the additional category of:

(g) Development project with management and legal issues (DPComplex).

Identifying further patterns of the IDL, we used the software DatacrackerFootnote 32 to analyze the relationship between the threat categories and other variables, such as region, type of site, and length of time on the list.

Finally, as one of the main purposes of this study was to evaluate the IDL as an NCP, we also collated information about the actors that have requested inclusion on the IDL (such as the state, an advisory body, or the Committee). This information could be inferred from the statutory records of the Committee. By examining whether and how frequently either states themselves and/or other actors (such as the advisory bodies) request a listing, valuable information about the use of the IDL as an NCP was uncovered. It should be noted, however, that controversies surrounding non-compliance commonly surface in arguments against inclusion on the IDL.Footnote 33 These cases were not captured through the data, which includes only properties actually listed on the IDL. Further empirical research (particularly case studies) would be welcome in that regard.

4. FINDINGS

This part presents the findings from our data analysis, starting with the overall composition of the IDL and then proceeding to discuss its functions.

4.1. The Composition of the IDL

A central theme in World Heritage research is the issue of balance or, more accurately, the absence thereof.Footnote 34 The issue of balance is structured around two core main concerns: the imbalance between (a) types of site included on the World Heritage List, and (b) geographic representations on the World Heritage List. In addition to cultural dominating over natural sites, there is also an overweight of certain types of cultural site, such as monumental and Christian sites compared with, for example, archaeological sites and associative cultural landscapes. Geographically, certain states (e.g., Italy, China, Spain, France, Germany, and India) and regions (Europe) dominate the World Heritage List whereas other regions (e.g., the Pacific and the Caribbean) and states (e.g., Burundi, Niue, Jamaica, and Samoa) are poorly, if at all, represented.Footnote 35 Moreover, recently researchers have exposed how these empirical biases of the World Heritage List are linked to state representation on the Committee.Footnote 36 As discussed further below, these different facets of balance/imbalance are also prevalent, if in an inverted pattern, on the IDL.

Historically, sites included on the IDL have been located in 54 different states (representing around 28% of the state parties to the Convention). Rather than being dominated by European nations, which are over-represented in the actual World Heritage List, it is the Arab and African states that dominate both the historic and current IDL. Together they account for around 60% of the sites on the current IDL.Footnote 37

The breakdown of cultural as opposed to natural and mixed sites is also interesting to consider. The data shows that cultural sites on the IDL outnumber the natural sites as follows. Historically, the 57 cultural sites account for 63% of IDL sites, the 33 natural sites account for 36%, with the lone mixed site accounting for 1%. The current IDL consists of 70% cultural sites (38), 30% natural sites (16), and zero mixed sites listed. Yet, when comparing the current World Heritage List and both the historic and current IDL, natural sites are over-represented on the IDL (Table 1A). Breaking down the types of site included on the IDL, it is apparent that a pattern of ‘geographical imbalance’ persists. Historically, the region with the most natural sites on the IDL is Africa. Cultural sites on the IDL are largely found in Arab states (Table 1B). Furthermore, the data shows that sites in Africa remain for far longer than the average time on the IDL, and sites in the Arab states average the least amount of time (see the Appendix at the end of the article).

Table 1A Division between Types of Site on the World Heritage List, July 2017

Notes

Table 1A shows a division between types of site on the entire World Heritage List as at July 2017 (N=1073), namely the current In Danger List (N=54) and the historic In Danger List (1978–2017, N=91).

All tables are produced by the authors.

Table 1B Regional Representation of the Lists

Building further on the challenge of imbalance within the World Heritage framework, another interesting contrast emerges when examining the relationship between states on the Committee and inclusions on the IDL. For instance, Bertacchini and Saccone found that Committee members on average nominate a higher number of sites for inclusion on the World Heritage List than state parties not represented on the Committee.Footnote 38 This indicates that states are able to use their presence on the Committee potentially to push through sites in their own territories. The data in this article shows that, conversely, the vast majority of the historic In Danger listings (89%) occurred when state parties were not represented on the Committee. In fact, 25% of the sites included on the IDL were located within states that have never been represented on the Committee. This suggests that states on the Committee can deflect concerns about In Danger listings from their own sites and that those without Committee representation are unable to do so.Footnote 39

4.2. The Functions of the IDL

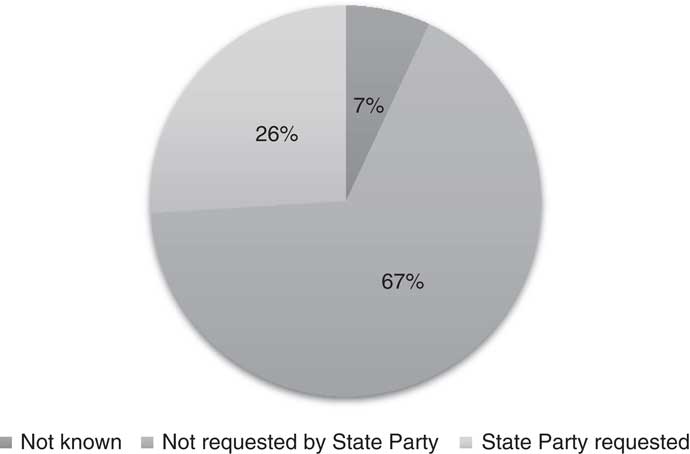

To discuss how the IDL functions, or is intended to function, it is necessary to consider the reasons for listing in combination with the party that initiated the listing. Starting with a general overview of the latter, one can observe that around a quarter of all sites on the IDL were initiated by the states themselves (Figure 1), with the African states representing the region with most requests (28%). This is narrowly followed by the Arab states (27%) and the remaining regions (all at 25%, Table 2). The advisory bodies, often in concert with UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre, represent another quarter of the requests. The involvement of the advisory bodies and the World Heritage Centre is, however, far greater when taking into account their active part in RMMs (about 20% of all In Danger requests). Accordingly, both the advisory bodies and the World Heritage Centre have taken an active role in activating the IDL and can be considered to have been directly involved in at least 45% of the In Danger requests. Although they make the final decision in all cases, the data indicates that the Committee (including its Bureau) has actively proposed inclusion on the IDL in just over 20% of all cases. The remaining are either not known or have been requested by the Director General of UNESCO (Table 3). This pattern indicates that different actors may use the mechanism for different purposes.

Figure 1 Historic Overview of State Party Request for In Danger Listing (N=91)

Table 2 Historic Regional Overview over States Request for In Danger Listing (N=91)

Notes

SP = state party. Other actors include advisory bodies, World Heritage Centre, Mission, Director-General UNESCO, World Heritage Committee and Bureau.

Table 3 Historic Overview of Actors Requesting In Danger Listing and the Reasons for the Listing (N=91)

Notes

Parties requesting listing: AB = advisory bodies; Mission = Missions including but not limited to representatives from AB/WHCentre; Other = Director-General UNESCO and not known; SP = state party; WHB/WHC = World Heritage Bureau/Committee; WHCentre = World Heritage Centre.

Reasons for listing: DP = development project; DPComplex = development projects with management and legal issues; ED = environmental degradation; MCI = material conservation issues (cultural); MLI = management and legal issues; ND = natural disasters; O = other, WCU = war and civil unrest

War and civil unrest: Activating the fire alarm

The predominant reason for inclusion on the IDL is war and civil unrest. On average, threats arising from war and civil unrest account for around 40% of all sites listed. It is also the most common reason for the inclusion of both natural and cultural sites on the IDL (Table 4).

Table 4 Historic Overview of the Reasons for In Danger Listings, 1978–2017 (N= 91)

Notes

For abbreviations, see Table 3.

Historically, over 60% of the war and civil unrest inclusions on the IDL are located in African and Arab states (Figure 2). Not surprisingly, ‘war and civil unrest’ as a reason for listing peaks as war and civil unrest break out and illustrates how heritage sites are drawn into national and international conflicts and, more specifically, how the IDL is often activated in times of turmoil.Footnote 40 For example, war and civil unrest as a reason for listing first peaks in the 1990s (with the wars in the former Yugoslavia and Zaire) and then peaks again in the 2010s (following the Arab Spring), as indicated by the inclusion on the IDL of several cultural sites in Libya, Syria, and Yemen. It is worth noting that these sites are in areas of civil war and/or unrest which are localized to where the fighting occurs rather than spread across whole continents or regions. Examining the relationship between reasons for listings with those responsible for initiating the requests, states most commonly request inclusion on the IDL precisely when sites are threatened by war and civil unrest (54%). This indicates that states use the IDL for its ‘fire alarm purpose’. Moreover, it shows that the symbolic nature of cultural heritage sites, in particular, make them targets for attacks which are likely to receive international attention and thereby draw attention to the (emerging) conflict writ large.Footnote 41

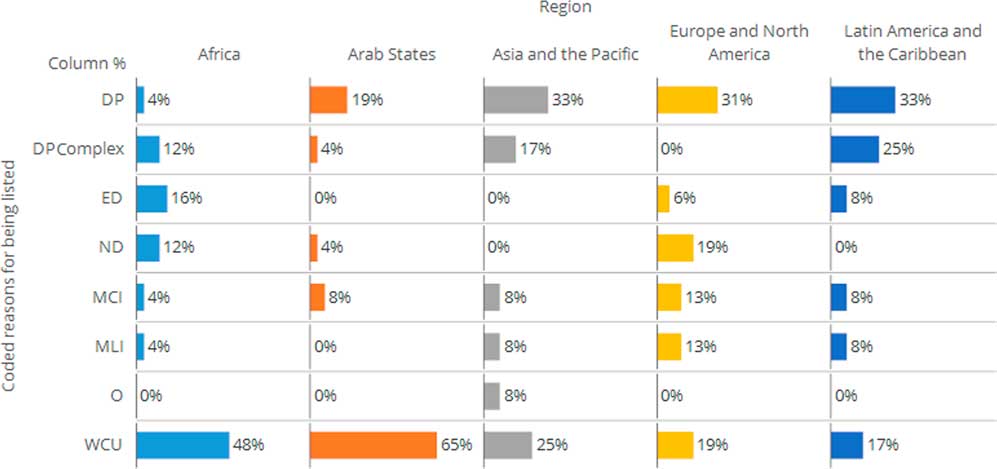

Figure 2 Historical Overview of Reasons for In Danger Listing divided by Region (N=91) Notes For abbreviations, see Table 3.

The regulatory use of the IDL as a fire alarm seems less about punishing or shaming the state into compliance and more about a collective call for action at the site itself, especially from the international community. However, in cases where sites have been listed In Danger on the ground of war and civil unrest, the data suggests that they may be kept on the IDL for many years without any progress towards their removal. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), for example, several sites were inscribed in 1994 for reasons of war and civil unrest. All currently remain on the IDL despite actions for their protection by both state and non-state actors. These statistics undermine UNESCO’s view of the IDL as a supposed mechanism for ‘exceptional action for an emergency measure of limited duration’.Footnote 42 Indeed, the challenge of intervening and ensuring that the IDL can actually function as a fire alarm was part and parcel of Italy’s proposal to revise the WHC in 1992 (at a time when the Balkans were war-ridden). In its original proposition it was noted that ‘[t]he present legal framework is not conducive to swift, vigorous action in situations of urgency and real danger. The international community and, therefore, UNESCO and the World Heritage Committee are unable to take any action in such situations’.Footnote 43 Even though the Convention text itself was never revised, aspects of the proposal were dealt with through revisions to the Operational Guidelines, which included, for example, a stronger emphasis on monitoring of at-risk sites.Footnote 44 While our analysis does not provide any clear answers as to whether this has had an impact, Meskell argues that World Heritage sites, and indeed new nominations, seem to be increasingly drawn into transnational conflicts.Footnote 45 Moreover, responding to the 2012 attacks on Timbuktu (Mali), the Chairperson at the time captured the prevailing challenge to which Italy had alluded two decades earlier, noting that ‘[a]ll we have are computers, papers and pens …You’re dealing with bandits and criminals and we only have paper and pens’.Footnote 46

Based on the data gathered, it seems clear that the fire alarm has most commonly been activated by states in situations of war and civil unrest. However, as will be discussed below, the fire alarm can and has been activated for other reasons.

Threats caused by development: The IDL as a disciplinary mechanism

After war and unrest, human-led developments in or around a World Heritage site constitute the second most common reason for inclusion on the IDL. Development projects are the cause of approximately 30–40% of the In Danger listings for the period 1990–2017 (Table 5). Moreover, as indicated in Table 5, over time these projects seem to be increasingly intertwined with other regulatory problems at the domestic level (including lack of legislation, absent management plans at sites, and so on).

Table 5 Overview of the Threats resulting in In Danger Listings based on the Year Sites were In Danger Listed

Notes

For abbreviations, see Table 3.

Threats arising from development pressures are most common in the regions of Asia-Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, followed by Europe and North America (Figure 2). Development threats are more often combined with managerial and legal issues in the Asia-Pacific and Latin American/Caribbean regions than they are in Europe and North America. This is likely to reflect the fact that protected area frameworks in many parts of Western Europe and North America predate the WHC.Footnote 47 In contrast, regulatory approaches in the Asia-Pacific region, Latin America and the Caribbean are either in the course of development, or suffer from a broader array of governance challenges, such as under-resourcing, corruption, poor transparency and accountability.

When examining the relationship between reasons for inclusion on the IDL and the actors that initiate the request, the following conclusion emerges. States seem less likely to request inclusion on the IDL when inappropriate developments pose a threat to their World Heritage sites. For example, only 8% of sites on the IDL that were initiated by states concern development projects. This stands in stark contrast to inclusions on the IDL initiated by RMMs, the World Heritage Centre and the advisory bodies, where inappropriate development accounts for 44% of total requests (Table 3). These differences are particularly visible in some of the better-researched IDL cases such as Liverpool (United Kingdom), Cologne Cathedral (Germany), Dresden Elbe Valley (Germany), Kakadu (Australia), the Great Barrier Reef (Australia), the Historic District of Panama City (Panama), and Venice (Italy). In all of these cases, states took an active stance against inclusion on the IDL,Footnote 48 although the extent to which these states succeeded in opposing the IDL varies. Australia, for example, succeeded in opposing the inclusion of both Kakadu and the Great Barrier Reef on the IDL, as has Italy (Venice) and Panama (Panama City). On the other hand, following years of opposition and negotiation, the World Heritage sites of Liverpool, Cologne Cathedral and Dresden Elbe Valley were all placed on the IDL as a result of inappropriate developments. Of these three sites, Liverpool remains on the IDL, while Cologne Cathedral was removed after two years. In 2009, Dresden Elbe Valley was deleted from the World Heritage List altogether.

All of this implies that the IDL can be used as a disciplinary tool by the World Heritage bodies, particularly in the context of inappropriate developments. The fact that most requests for inclusion on the IDL are initiated by the World Heritage bodies (rather than the states themselves) establishes an intention to use the IDL as a punitive measure where a state has breached the rules of the WHC. The use of the IDL in this way can touch on both procedural and substantive rules. For instance, a state party’s failure to comply with notification procedures under paragraph 172 of the Operational Guidelines (the requirement to notify the Committee about a potentially damaging development) may result in a RMM to the site. There are several recent examples of this pattern occurring, which include the Ancient city of Thebes and its Necropolis (Egypt);Footnote 49 the Old Town of Regensburg with Stadtamhof (Germany);Footnote 50 Kaziranga National Park (India);Footnote 51 Ibiza (Spain);Footnote 52 the Ancient City of Nessebar (Bulgaria);Footnote 53 and the Great Barrier Reef (Australia).Footnote 54 Thereafter, the Committee may ‘require’ the state to establish a long-term plan, or undertake a strategic environmental assessment of the broader risks in order to ward off inclusion on the IDL.Footnote 55 It should be noted that while the Committee may be relatively comfortable in using the IDL as a disciplinary tool, it has been reticent to list sites In Danger as a result of climate change despite pressure from non-state actors for it to do so.Footnote 56

5. THE IDL AS A REGULATORY TOOL IN TRANSNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW

The empirical findings presented above have relevance for a deeper understanding of compliance and enforcement within the context of transnational environmental law. As Heyvaert points out, environmental regulation – that is, the creation and enforcement of rules relating to human conduct that impact upon the environmentFootnote 57 – is becoming increasingly transnational in its character.Footnote 58 Moreover, this development in regulation worldwide does not seem to be restricted to the field of environmental protection.Footnote 59 While recently there has been a focus on the actors involved in regulation, including both state and non-state entities,Footnote 60 as well as how to make domestic regulation more effective or ‘smarter’,Footnote 61 comparatively little work has been done on the mechanisms for ensuring effective control of environmentally harmful activities at the transnational level. Below, therefore, we further discuss the ‘dual’ regulatory aspects of the IDL raised in this article with the aim of opening this field of inquiry further.

5.1. The Use of the IDL as a Fire Alarm

The IDL mechanism can operate like a fire alarm – effectively a ‘call to arms’ for the advisory bodies, the Committee, other member states and non-state actors to marshal their resources to prevent any lasting damage to the site. The data from the study shows how the fire alarm can be activated by states when war and civil unrest threaten sites. This analogy of a fire alarm can be further extended and nuanced through, firstly, further legal analysis and, secondly, in-depth empirical studies of specific sites. Starting with the former, the analogy of a fire alarm in regulatory terms, or ‘fire alarm signal’,Footnote 62 appears to have been covered first in an American domestic context by McCubbins and Schwartz in 1984.Footnote 63 They presented the fire alarm as an alternative monitoring technique to ‘police oversight’ of US congressional activities:

Analogous to the use of real fire alarms, fire-alarm oversight is less centralised and involves less active and direct intervention than police-patrol oversight … a system of rules, procedures and informal practices [are established] that enable individual citizens and organised interest groups to examine administrative decisions … and to seek remedies from agencies [and] Courts.Footnote 64

The fire alarm monitoring analogy was more recently applied in an article by Abbott, Levi-Faur & Snider on ‘theorizing regulatory intermediaries’, in which they suggest that certain non-state actors can play ‘especially active roles in monitoring (typically through fire-alarm mechanisms), if they have the capacities to do so, and [also] in providing feedback on the effectiveness of regulation’.Footnote 65 Although these conceptions discuss the fire alarm model in a domestic regulatory context, the analogy has similar application at a transnational regulatory level, including, for example, with regard to the IDL. Viewing the IDL as a fire alarm has two distinct advantages. Firstly, as Abbott and others suggest, it legitimizes the attention and possibly the presence of non-state actors such as interest groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the media at particular World Heritage sites regardless of where they are located in the world. This illustrates the transnational character of the tool. The IDL mechanism provides non-state actors (NGOs, the media, corporations, and so on) with a clear basis on which to argue for research funding, immediate conservation and rehabilitation, or even additional security and military assistance for sites that may be under threat from war or civil unrest. This is a form of automatic ‘enrolment’Footnote 66 of civil society and can occur even where the IDL is not formally made – for example, where there is a threat of a listing raised by the advisory bodies, other states and/or the Committee. In such a case – which might be labelled a ‘first alarm,’ or alternatively an ‘intention to release the alarm’ scenario – non-state actors can still be enlisted to act. In the case of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, for example, recent empirical evidence has shown how non-state actors used the threat of a listing ‘like a sword of Damocles’ hanging over the head of the Australian government to improve its domestic regulatory practices.Footnote 67 Since the IUCN first signalled the intention to raise the alarm through an RMM in 2012, the Australian government has invested an additional USD 370 million to tackle pollution and breed more resilient coral.Footnote 68 It is therefore conceivable that as a fire alarm the IDL could become an effective mechanism for encouraging and legitimating the participation of non-state actors in regulatory activities – a key component of effective transnational governance.Footnote 69

This use of a fire alarm system to engage third parties at the transnational level also aligns with the work of authors like Cafaggi, who distinguish between public transnational regulation and private transnational regulation. Whereas public regulation is conducted by state agencies, the practice of private transnational regulation, says Cafaggi, is undertaken ‘pursuant to independent decisions of private actors and schemes issued under the political pressure of public actors and the media’.Footnote 70 The fire alarm system effectively provides a space for private actors to create political pressure both in a domestic context and at the transnational level. Drawing again on the Australian Great Barrier Reef IDL example, several European-based multinational banks withdrew their support for developments that were likely to harm the World Heritage site. Arguably based on shareholder concerns, these banks rightly or wrongly imposed their own standards on investment, which resulted in the withdrawal of funding for projects which might put at risk the World Heritage listed Great Barrier Reef. Much of this was a consequence of NGO campaigning in Australia and Europe.Footnote 71 One could see this as a way of non-state actors being involved in transnational regulation despite the fact that a formal delegation of regulatory responsibilities had not occurred.Footnote 72

A second advantage of the IDL as a fire alarm at the transnational level is that it raises a moral responsibility (if not a legal one) for other states to respond and assist the state that may be struggling to defend its World Heritage. Such a response would be in line with the ‘Common Heritage of Mankind’ principle which underpins the WHCFootnote 73 and, more specifically, a thorough implementation of the erga omnes obligations that exist within the text of the Convention.Footnote 74 Erga omnes refers to ‘the good of all’ or ‘towards everyone’. It effectively means that one state has obligations for its sites which extend to all parties under the Convention.Footnote 75 It follows that where the IDL alarm can be raised, and where the state in question is unable to conserve the site, other states are arguably justified in sharing their resources and expertise with the state in which the threatened site is located.Footnote 76 This would also seem to satisfy the communal nature of conservation assistance under the Convention, for example, as stipulated in Article 4 of the Convention: ‘[A state] will do all it can … to the utmost of its own resources and, where appropriate, with any international assistance and co-operation, in particular, financial, artistic, scientific and technical, which it may be able to obtain’.

That said, there are disadvantages in promoting the IDL as a fire alarm. Firstly, as McCubbins and Schwartz point out, ‘fire-alarm oversight can be [just] as costly as police-patrol oversight [and] much of the cost is borne by the citizens and interest groups’.Footnote 77 Secondly, the fire alarm is by no means instantaneous. Under the World Heritage system, an In Danger listing requires a recommendation (usually following a mission) from the ICOMOS or the IUCN, which must then be put before the Committee, which may or may not agree to it. Although the threat of an In Danger listing can be an alarm in itself, the effectiveness of the IDL as a true fire alarm model is limited by the bureaucratic and, at times, sluggish way in which it is implemented.

5.2. The IDL as a Disciplinary Instrument

The approach of ‘naming and shaming’ non-compliant actors has a relatively long history in regulatory literature (and criminal law more generally). As Van Erp refers to it, a ‘reputational sanction’Footnote 78 essentially involves publicly identifying the particulars of a breach and sharing that information with a broader group. That broader group can include other regulated actors (here, state parties to the WHC) or alternatively the public at large, with the latter allowing the widest possible reach for dissemination of non-compliant behaviour. Whether naming and shaming is effective as a regulatory tool, however, is an open question. The answer is likely to turn on individual states, their reputations on the diplomatic stage (in both environmental treaties and trade negotiations), their attitude towards development and heritage, and, ultimately, whether they can be ‘pulled towards compliance’.Footnote 79

More broadly in the international relations literature, much has been written about why some states respond to international laws while others do not.Footnote 80 Guzman, for instance, writes that it is the nature of the promises made under international law (including erga omnes promises) that are closely related to a nation’s standing or reputation in global society:

A state known to honour its agreements, even when doing so imposes costs, can extract more for its promises than a state known to violate agreements easily. When making a promise, a state pledges its reputation as a form of collateral. A state with a better reputation has more valuable collateral and, therefore, can extract more in exchange for its own promises.Footnote 81

There may be some truth in this, but whether states respond to ‘the shame’ of an In Danger listing is likely also to turn largely on the nature of the local politics at that particular site. In the case of the delisting of the Dresden Elbe Valley (Germany), for example, local communities protested against UNESCO oversight. Even the threat of inclusion on the IDL was insufficient to stop the development by the local government.

6. CONCLUSION

The results of this study provide a preliminary snapshot of the IDL, and further work can build on this to present a clearer picture of how compliance with the WHC operates under transnational environmental law. Most importantly, the empirical analysis of the historic and current IDL finds that the IDL has been used mainly when World Heritage sites are threatened by either (i) civil unrest and war, or (ii) inappropriate developments taking place at or near the site. These findings resonate with the emerging literature on the list and the conclusion that there is something of a dual use of the IDL: as a fire alarm and as a disciplinary instrument for recalcitrant states. The two seem to be activated by different actors for different purposes.

The empirical analysis shows that states most commonly use the IDL as a fire alarm when civil unrest occurs. To a far lesser extent, states raise the fire alarm to draw attention to inappropriate development around World Heritage sites. At times when development projects threaten properties, non-state actors such as the advisory bodies or the World Heritage Centre commonly activate the fire alarm. When non-state actors activate the alarm, the IDL shifts to become a disciplinary instrument for ‘naming and shaming’ states into compliance. Hence, the two functions of the list do, at least at times, work in tandem rather than in opposition. The latter, however, is not readily apparent when looking at the IDL only in an aggregated manner, as done here. In order to gain further insights into how the fire alarm and the disciplinary mechanism work in relation to each other, further in-depth case studies of proposed and implemented In Danger listings are needed. Further research might possibly seek to focus on qualitative data from particular at-risk sites, including asking the question of how and why states have resisted (or complied with) threats of inclusion on the IDL.

APPENDIX

Overview of All In Danger Listings, 1978–2017