Introduction

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has a robust body of evidence to support the efficacy of this therapy in treating a number of mental health problems including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Duffy, Hackmann and Clark2002; NICE, 2005; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Keane, Friedman and Cohen2009; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Halpern, Ferenschak, Gillihan and Foa2010; Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Fuchkan, Huntley, Robertson, Thompson, Scragg and Ehlers2010; McLean and Foa, Reference McLean and Foa2011; Schnyder et al., Reference Schnyder, Ehlers, Elbert, Foa, Gersons, Resick and Cloitre2015). There is, however, a paucity of current empirical research and best practice guidelines evidencing the efficacy of CBT with refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture (Mørkved et al., Reference Mørkved, Hartmann, Aarsheim, Holen, Milde, Bomyea and Thorp2014).

It can be argued that much of the initial research for evidence-based PTSD treatments have focused on a single traumatic event or a specific type of trauma such as rape or Western veterans (Breslau, Reference Breslau2009; Buhmann et al., Reference Buhmann, Nordentoft, Ekstroem, Carlsson and Mortensen2016). Consequently, multiple or prolonged traumatic experiences may require an altered therapeutic approach (Cloitre, Reference Cloitre2009; Schauer et al., Reference Schauer, Neuner and Elbert2011). Systematic and clinical reviews indicate that there is no single superior psychotherapy intervention which is firmly supported to treat PTSD in refugee populations and survivors of torture (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Bryant, Silove and Steel2011; Tribe et al., Reference Tribe, Sendt and Tracy2017). This does not mean that current evidence-based trauma focused CBT interventions are not efficacious in refugee populations, but assumptions should not be made that the same levels of efficacy can be generalized in refugee populations and survivors of torture (Van der Veer, Reference Van der Veer1998; Neuner et al., Reference Neuner, Schauer, Roth and Elbert2002; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Halpern, Ferenschak, Gillihan and Foa2010). This does highlight that further research in this area is required to better understand the psychopathology associated with refugee populations in order to develop effective psychological approaches to address some of the mental health needs that refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture can present with in therapy.

It could be argued that reflective practice has always been an implicit concept in CBT, and that this is an intrinsic part of CBT theory and clinical practice in interventions such as Socratic questioning and thought records (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). The absence of reflective practice can limit CBT therapists’ ability to deliver interventions, which can provide the client with optimum therapeutic outcomes (Haarhoff and Thwaites, Reference Haarhoff and Thwaites2015).

When added complexity is present, such as cross cultural work, comorbidity, language barriers and potential therapist beliefs about working with refugee populations, then reflective practice can be advantageous in improving therapist clinical practice and managing therapy challenges (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014). Therefore, in the context of limited current empirical research, reflective practice can be a useful approach to assist in improving treatment outcomes and enhance clinical practice when working with population groups where increased complexity may be present.

Definition of refugees and asylum seekers

The term refugee is defined in the Refugee Convention (UNHCR, 1951, p. 14) as someone who is:

‘. . .owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country. . .’

Whilst the term asylum seeker refers to:

‘. . .Someone whose request for sanctuary has yet to be processed . . . ’ (UNHCR, 2018a). Often asylum seekers possess distinct limitations in the host country such as limitations on employment, housing, freedom of movement and other socio-economic activities.

Context of refugee mental health

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2018b) has recorded a global unprecedented number of people who have been displaced due to wars and political unrest. Such examples can be seen in countries such as Syria, which has caused many affected individuals to seek asylum and safety in other countries. In some cases, asylum seekers have sought safety from a violation of their human rights and harsh conditions which may include human trafficking, rape, persecution, politically organized violence and, for some, marginalization as a result of sexual orientation (Bhugra et al., Reference Bhugra, Craig and Bhui2010; Bronstein and Montgomery, Reference Bronstein and Montgomery2011; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones and Grais2014).

Epidemiological studies highlight the impact of both forced and voluntary migration (Bhugra, Reference Bhugra2004). Such studies identify that the stress of forced migration for some is immeasurable. In addition, forced migration and the exposure or experience of trauma as a result of war or torture places many refugees at an increased risk of developing mental health problems (NICE, 2005; Mitschke et al., Reference Mitschke, Praetorius, Kelly, Small and Kim2017). PTSD is arguably the most prevalent and researched psychological disorder identified in refugee populations (Johnson and Thompson, Reference Johnson and Thompson2008). Furthermore, the clinical presentation of comorbid symptoms is common and can include somatic or pain symptoms (Buhmann et al., Reference Buhmann, Andersen, Mortensen, Ryberg, Nordentoft and Ekstrøm2015), depression (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016) and anxiety disorders (Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Wittmann, Ehlert, Schnyder, Maier and Müller2014).

For some refugees and asylum seekers their traumatic experiences are not only multiple events, the process of experiencing trauma for some is also protracted from the point of exile to the process of seeking asylum and the assimilation and adjustment into a new country and community (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Davidson and Schweitzer2010; Kira and Tummala-Narra, Reference Kira and Tummala-Narra2015; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Ghaderi, Eriksson, Lauri, Kukacka, Mamish and Visser2017). Additional traumatogenic factors can negatively impact refugee populations. These may include ongoing anxiety due to family members who remain in the country which they left to seek asylum, marginalization in their new country, loneliness, relative poverty, loss and grief (Beck, Reference Beck2016). As a result, developing social networks in the UK can be difficult for some refugees and asylum seekers. Refugee populations who present to IAPT for a psychological intervention may meet the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) diagnostic criteria for one or more psychological disorders.

Survivors of torture

The Istanbul Protocol are international guidelines published by the Office of United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2004, p. 1) and defines torture and provides guidance for assessing torture and other inhumane or degrading treatment as follows:

‘Torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person, has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.’

Not all refugees and asylum seekers are necessarily survivors of torture but inevitably this is relatively likely (Regel and Berlinger, Reference Regel and Berliner2007). Survivors of torture may present to services with complex needs, and clinical presentations may include depression, anxiety and PTSD (Istanbul Protocol, 2004). There are very few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which evidence the utility and efficacy of CBT interventions with survivors of torture (Başoğlu et al., Reference Başoğlu, Ekblad, Bäärnhielm and Livanou2004), but there are some clinical studies which evidence positive treatment outcomes of CBT when used with survivors of torture (Başoğlu et al., Reference Başoğlu, Ekblad, Bäärnhielm and Livanou2004; Regel and Berlinger, Reference Regel and Berliner2007; Bashir, Reference Bashir and Boyles2018).

It is not the intention of this paper to take a position on whether or not survivors of torture should receive treatment in brief therapy settings such as IAPT, but to explore how effective reflective practice can assist CBT therapists to develop resilience and improve individual clinical practice should a client disclose torture at any point in the therapy process, or if the therapist suspects that torture may have taken place at some point in the client's trauma history.

Disclosures of torture may not be made to the CBT therapist by the survivor of torture due to factors such as shame and guilt as a result of the trauma (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert1997; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Scragg and Turner2001). It is therefore important to consider when working with refugee populations who disclose torture at the start of therapy or even much later into therapy, that in such cases reflective practice and clinical supervision are employed as summarily as possible. Effective reflective practice and clinical supervision are necessary to assist the CBT therapist to process their own clinical experience, to process any implicit and explicit assumptions of survivors of torture, identify therapist fears or training needs as well as explore the limitations of brief therapy when working with complexity; equally, exploring the strengths of brief therapy to provide adaptive evidence-based interventions to reduce some level of client distress before an onward referral to a specialist service or longer term psychotherapy is made.

Current context of IAPT services in the UK

Since IAPT's evolution in England in 2008, its services are identified as a first-line primary care service provision to treat depression and anxiety disorders including PTSD using evidence-based psychological therapies (Cormac and Mace, Reference Cormac and Mace2008; Clark, Reference Clark2018; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Canvin, Green, Layard, Pilling and Janecka2018). IAPT has a planned expansion to increase the access to psychological therapies to at least 1.5 million people by 2021 (Clark, Reference Clark2018). This may mean for many refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture, IAPT maybe the first point of contact with a mental health service.

Whilst IAPT services are generally commissioned to treat mild to moderate clinical presentations, the Istanbul Protocol (2004) suggests that PTSD symptoms can fluctuate over prolonged periods of time. This highlights for some survivors of torture which might include refugees or asylum seekers may not present with severe PTSD symptoms initially, but may identify the most distressing current symptoms they are experiencing such as depression, grief, adjustment or interpersonal problems with family or friends. In such cases trauma therapy essentially might not be the client's initial intervention choice. Sleep hygiene, behavioural activation or psychological education on anxiety may be the appropriate treatment intervention in such cases.

Language barriers

Psychotherapy in all forms can be viewed as a Western construct and process (Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Kirmayer, Reference Kirmayer2007), therefore a shared understanding of the clients’ expectations of therapy and understanding of trauma and mental health as a whole should be established with the client, the therapist and interpreter if present.

Working through interpreters is not identified as a key competency on IAPT postgraduate training courses (Mofrad and Webster, Reference Mofrad and Webster2012; Tutani et al., Reference Tutani, Eldred and Sykes2018), which can cause some IAPT therapists to feel ill equipped or create additional challenges when working with refugee populations who require an interpreter in therapy. The requirement of an interpreter should not be a reason why psychological interventions including CBT are withheld from refugee populations (NICE, 2005; Dubus, Reference Dubus2016; Tutani et al., Reference Tutani, Eldred and Sykes2018).

Whilst studies such as D'Ardenne et al. (Reference D'Ardenne, Ruaro, Cestari, Fakhoury and Priebe2007) identify that the use of interpreters in clinical practice does not necessarily hinder therapeutic outcomes, nevertheless the use of an interpreter may increase a level of complexity in the therapeutic relationship (BPS, 2017). In addition, psychological therapies should be adapted to include and incorporate the culture and contextual experience of the client (Beck, Reference Beck2016). It is in such instances that reflecting on clinical practice is paramount to evaluate and identify if the CBT therapists’ practice is meeting the need of the client. The learning gained from reflective practice if applied effectively can assist to enhance the therapists’ clinical practice when working with refugee populations or survivors of torture.

Reflective practice

There has been a significant increase in the development of empirical research and studies on the role of reflective practice, self-practice and self–reflection (SP/SR) within the field of CBT in the last decade (Bennett-Levy and Padesky, Reference Bennett-Levy and Padesky2014; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015). Reflective practice is a learning process that involves reflecting on or reviewing clinical practice and clinical experience and may incorporate the therapists’ personal reactions, emotions, beliefs and behaviours (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Stedmon and Dallos2009). Reflective practice can be experienced in a variety of formats which can include, but is not limited to, reviewing therapy recordings, reviewing clinical experiences, reflective journals or reflective blogs (Farrand et al., Reference Farrand, Perry and Linsley2010) and can be used within the context of clinical supervision or self-supervision.

Reflective models such as Kolb (Reference Kolb1984) and Gibbs (Reference Gibbs1988) are often an inherent part of the academic assessment process for some trainee post-graduate CBT therapists to develop reflective practice skills (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001). Such models should still be encouraged and used to develop reflective practice. The use of the critical incident analysis model is also a reflective model that could be utilized as an additional model to be used in IAPT to aid reflective practice in clinical practice settings.

Critical incident analysis model

A critical incident analysis has its origins as a reflective tool for social work practitioners and trainees (Lister and Crisp, Reference Lister and Crisp2007), although its earlier origins were initially developed during a World War II Army Air Forces Aviation psychology programme (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan1954). This model was used to investigate mishaps or errors which had happened. Consequently, the process of reflection enabled learning to take place. Most importantly, this model lends itself to being generalized and replicated in other fields including healthcare (Woloshynowylh et al., Reference Woloshynowych, Rogers, Taylor-Adams and Vincent2005).

The critical incident analysis as a tool should not lend itself to be used as a punitive measure in clinical practice which is only implemented when serious incidents have taken place. Rather its use should be encouraged as a reflective model, which can be used regularly to help identify good clinical practice as well as identify practice which encourages learning and reflection to take place (Lister and Crisp, Reference Lister and Crisp2007; Mahajan, Reference Mahajan2010).

The structured process of reflection within the critical incident analysis model differs in some aspects to Kolb's (Reference Kolb1984) and Gibbs’ (Reference Gibbs1988) model in its emphasis of the assimilation of theory into clinical practice in order to optimize learning and enhance clinical practice simultaneously.

Structure of the critical incident analysis

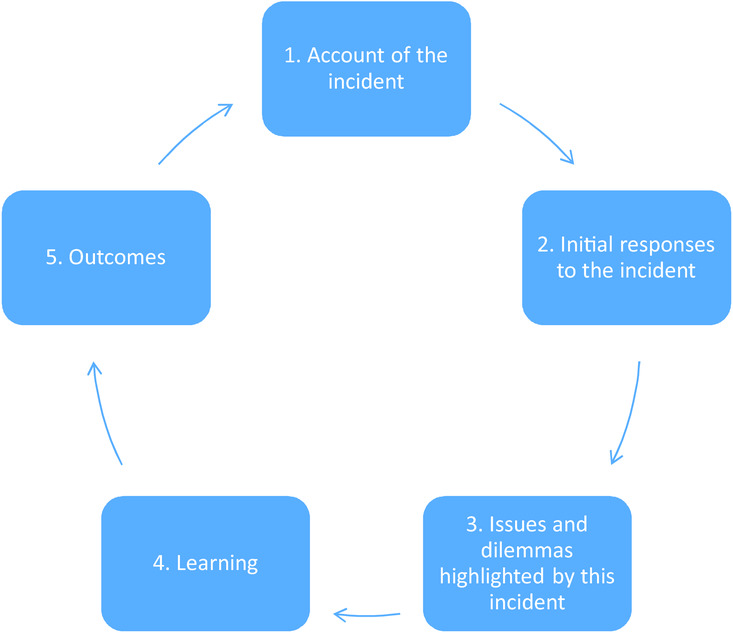

Lister and Crisp (Reference Lister and Crisp2007) recommend a framework that consists of a five-stage process:

(1) Account of the incident

• Details of the incident, what actually happened, who was involved, where and when did it happen?

• At the point of the incident what was the purpose and context of your contact or intervention at the time?

(2) Initial responses to the incident

• What cognitions and emotions were you experiencing at the time of the incident? A formulation cycle may be useful at his point.

• What were the reactions or responses of the client or other individuals involved? If this is unknown, do you hold any assumptions of perceived responses?

(3) Issues and dilemmas highlighted by this incident

• Are there any clinical practice dilemmas that have emerged as a result of the incident?

• What are the ethical issues (if any) or values that this incident has highlighted?

• Are there any inter-agency or interdisciplinary relationships that need to be, or should be, identified as a result of this incident?

(4) Learning

• On reflection, what have you learnt about yourself, therapist self, clinical practice or relationship with others? This can include organizational policies and procedures.

• What theoretical perspectives or research has, or could have, assisted to develop a better understanding about some aspects of this incident?

• How might a wider understanding of organizational policy or legislation have helped to understand this incident further?

• What future learning needs have been identified due to this incident and how can such learning needs be achieved? By when? With whom?

(5) Outcomes

• What are the agreed outcomes as a result of the incident?

• How (if any) has this incident contributed to any changes in your clinical practice?

• What are your cognitions and emotions about the incident now?

A brief clinical case example

The critical incident analysis model will be explored further. The case example involved working with a female client from Egypt who was a refugee attending a CBT initial assessment and presented to IAPT as a result of PTSD symptoms and comorbid depression. The initial traumatic experience happened in Egypt but the journey of exile from Egypt to Europe created additional traumatic experiences. Furthermore, the process of assimilation into the UK and into her local community created additional difficult experiences. The client's current isolation, loss and adjustment into the UK had also compounded her clinical presentation. An Arabic interpreter was required to aid the therapy process.

Figure 1. Critical incident analysis model (Lister and Crisp, Reference Lister and Crisp2007)

(1) Account of the incident

Three individuals were present, the therapist, the client and the employed, professional interpreter. The purpose of the intervention was to carry out a CBT assessment. The appropriate trauma measures and IAPT measures had been completed.

To avoid translating errors and reduce misunderstandings, the therapist reported that the interpreter was asked before the session to relay only the exact answers from the client (from questions which the therapist asked) and was asked not to summarize the client's feedback as best as possible or ask any additional questions to the client. However, on numerous occasions the interpreter appeared to have frequent, prolonged dialogues with the client in the session, despite the interpreter being asked not to do this to ensure that the client's actual responses were captured.

(2) Initial responses to the incident

The therapist reported that during therapy they experienced thoughts of confusion and feelings of frustration towards the interpreter. This caused the therapist to also experience increased levels of anxiety. The therapist reported that these emotions and cognitions made it difficult to retain eye contact and develop some level of rapport with the client. The therapist reported that the communication process appeared unclear as the responses did not appear to correlate with the questions that had been asked by the therapist. This made it difficult to decipher if this was the client's actual response or the interpreter's summary of the response.

The therapist reported that the interpreter was asked on several occasions if they were clear about the therapist's instructions regarding communication, at which point the interpreter stated that they had understood the therapist's request to only interpret exactly the questions and responses of both the client and therapist. The therapist reported that the client also appeared somewhat confused at times in the session, but could not be completely sure of this.

A formulation cycle was completed immediately after the session by the therapist to capture the therapist's cognitions, emotions and behaviours in the moment.

(3) Issues and dilemmas highlighted by this incident

The NICE (2005) clinical guidelines for PTSD recommend the use of an interpreter when working with refugees and asylum seekers. The use of an interpreter was essential and necessary for this client. The therapist reported that this incident highlighted the interpersonal and clinical challenge of balancing the relationships between the client, the therapist and the interpreter at the same time.

The therapist reported that the interpreter later disclosed at the end of the assessment session, that the interpreter had professionally supported the client in other professional contexts such as solicitor and Home Office appointments as an interpreter and therefore had met the client previously on several occasions.

No formal complaint was deemed necessary at this point.

(4) Learning

Although the therapist had a lot of experience of working with refugees, asylum seekers and interpreters in therapy, the therapist reported that on reflection noticing the interconnectedness of emotions, cognitions and behaviours within the therapist is just as important as noticing it in the client particularly when strong emotions arise in the therapy context. The therapist reported finding it difficult to mask some of their own frustrations whilst in the session and was able to acknowledge how this may have negatively impacted the therapeutic process. The therapist reported that on reflection using the critical incident analysis model provided a helpful and pragmatic structure to process this challenging experience and associated difficult emotions.

Theoretical perspectives used to help inform the therapist of what may have been taking place in the session include Farooq and Fear (Reference Farooq and Fear2003) and Cecchet and Calabrese (Reference Cecchet and Calabrese2011) which include ‘omission’ and ‘role exchange’. Omission is identified as a process where the interpreter excludes some of the client's feedback during the interpretation and ‘role exchange’ is identified as a process where the interpreter asks his or her own questions instead of the therapist's questions (Cecchet and Calabrese, Reference Cecchet and Calabrese2011). Exploring the complexity and existing theories in relation to working with interpreters in therapy assisted the therapist to become aware of processes that may have been taking place in the session and within the therapist.

The therapist reported that being aware of an existing professional relationship or previous professional contact by the client and interpreter in other legal contexts such as solicitor or Home Office appointments may have created an opportunity for the interpreter to act as an ‘advocate’ for the client in such settings (Cecchet and Calabrese, Reference Cecchet and Calabrese2011). However, in the therapy process this can hinder transparent and clear communication between the therapist and client. Other potential challenges include the client developing a strong alliance predominantly with the interpreter and very little with the therapist. This can also create some difficulty for the therapist to develop a therapeutic relationship with the client (Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005).

Future learning for this therapist involved further reading about different models and approaches of working with interpreters as a triad (Mofrad and Webster, Reference Mofrad and Webster2012) and managing this dynamic effectively in clinical practice (Tutani et al., Reference Tutani, Eldred and Sykes2018).

(5) Outcomes

The therapist reported that a key outcome as result of using the critical incident analysis involved constructing a set of written, concise and clear guidelines which were used at the start of each therapy session when an interpreter was present. The guidelines were developed to create clarity of the role of the interpreter and therapist within the therapy context, which as a practice is endorsed by Tribe and Morrissey (Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004). The expectations of the interpreter was also translated by the interpreter to the client to ensure that the client was also aware of the interpreter's role in the therapeutic context. The therapist reported that the guidelines had assisted them in managing the triad therapeutic relationship when working with interpreters in therapy.

The therapist reported that the learning which had taken place as a result of using the five-question critical incident analysis, provided a structured framework which encouraged identification and reflection of the processes within the session, but also provided an appropriate context that encouraged processing the therapist's behaviours, emotions and cognitions. The therapist reported that the learning which was gained was a contributing factor in improving their own clinical practice, particularly when working with complex presentations or diverse groups.

Evaluation of the model

Empirical research of the utility and efficacy of the critical incident analysis model to aid reflective practice in psychotherapy is required; however, this perspective can also be generalized to other existing reflective models such as Kolb (Reference Kolb1984) and Gibbs (Reference Gibbs1988).

An additional criticism includes time, as using the model could take up the full duration of an hour clinical supervision session due to the number of questions asked. Therefore a level of flexibility is necessary, which is a point endorsed by Flanagan (Reference Flanagan1954) and Lister and Crisp (Reference Lister and Crisp2007), as some questions may require greater or lesser time.

The brief case example demonstrates that reflective practice can be a beneficial tool to provide a helpful structure which can assist the learning process and ultimately enhance clinical practice. Whilst the critical incident analysis model may not be necessary for each client, it lends itself well as an adaptive reflective pedagogical approach to improve clinical practice.

Self-practice ‒ therapist beliefs

Working with refugees and asylum seekers can elicit strong emotions that may include feeling overwhelmed, helpless or powerless due to the clients’ current complex problems. Therapists may also experience anger at hearing about injustice suffered by the client. In clinical practice being aware of one's own personal judgements, discrimination and unhelpful perceptions gathered from early experiences, the media, lived experiences or social environment can be helpful to assist CBT therapists to identify where one's own thinking may have originated. This will aid an understanding of how these shape current personal beliefs and can impact clinical practice when working with diverse populations including refugees and asylum seekers.

Arguably the most effective method of truly learning and understanding CBT principles is to practise it in one's life on a frequent basis by using self-practice and self-reflection (SP/SR) (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015). The use of self-practice includes using interventions such as the ‘downward arrow technique’ (Fennell, Reference Fennell, Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk and Clark1989) to assist therapists to drill down to their beliefs which might influence unhelpful behaviours when working therapeutically with refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture. The use of thought records by the therapist can also be used to challenge unhelpful cognitions about the therapist or the therapist's clinical practice.

Reflective practice including SP/SR can be an adaptive approach that can be used to process challenging and difficult emotions and cognitions experienced by the CBT therapist. Reflective practice does not need to be an isolated process and can be incorporated within the context of clinical supervision to create a safe space for the therapist to process complexity experienced in clinical practice.

Clinical supervision

The use of clinical supervision is identified as one of three fundamental principles which underpin the IAPT model (Clark, Reference Clark2018) and is viewed as a critical aspect to support clinical practice within IAPT (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007). This highlights the significant role of clinical supervision for IAPT therapists. There has been an exponential growth in research in the last two decades identifying the importance and adaptive processes within CBT clinical supervision (Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2012). Effective clinical supervision can be viewed as an essential process that can assist CBT therapists to consolidate new skills, enhance existing skills and explore the possibility of future development (Bennett-Levy and Padesky, Reference Bennett-Levy and Padesky2014; Haarhoff and Thwaites, Reference Haarhoff and Thwaites2015).

CBT and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) are the recommended first-line psychotherapy treatment interventions for PTSD within IAPT (Clark, Reference Clark2018; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Canvin, Green, Layard, Pilling and Janecka2018). This potentially places CBT therapists at an increased risk of exposure to hearing and treating trauma memories than those working in other psychotherapy modalities. Trauma therapists, particularly those who work with refugees and survivors of torture, are at an increased risk of burn-out, compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma and experiences of symptomology associated with PTSD (Adams and Riggs, Reference Adams and Riggs2008). Moreover, such symptoms are heightened when work environments are challenging or unsupportive to the therapist (Deighton et al., Reference Deighton, Gurris and Traue2007). Consequently, the use of reflective practice and reflective models such as the critical incident analysis within clinical supervision can be an invaluable and supportive context to identify and process clinical challenges and essentially assist to improve clinical practice.

Reflective practice within the context of clinical supervision is not exclusive to being implemented only with therapists who work with diverse populations such as refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture, but should be an essential tool used to develop therapist resilience and to facilitate clinical development for all therapists.

Discussion

Refugee populations and survivors of torture are at an increased risk of developing PTSD and comorbid symptoms as a result of the trauma endured prior to seeking asylum and further trauma endured during exile and adjustment into a new country and culture. This protracted process can contribute to the development of mental health problems. This can provide IAPT therapists with various challenges including assessing the appropriateness of brief therapy or an onward referral to specialist services (if commissioned locally) or secondary care if appropriate. IAPT's planned expansion by 2021 (Clark, Reference Clark2018) means that IAPT services for some refugee populations may be the first point of contact with mental health provisions. This places some primary care IAPT practitioners at an increased risk of exposure to refugees, asylum seekers or survivors of torture disclosure of trauma at the point of assessment.

Language barriers may add an additional challenge. Whilst using an interpreter does not necessarily impact therapeutic outcomes (D'Ardenne et al., Reference D'Ardenne, Ruaro, Cestari, Fakhoury and Priebe2007), managing this triad relationship can present complex challenges, which was identified in the clinical case example. A lack of training in this area on IAPT CBT courses can cause some therapists to feel ill-equipped to manage this added dynamic in clinical practice. Post-graduate IAPT CBT courses should consider how best to develop competency and knowledge in this area of clinical practice.

There is a dearth of current empirical research within the last decade evidencing CBT's efficacy with refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture in a brief therapy context and in particular IAPT (Mørkved et al., Reference Mørkved, Hartmann, Aarsheim, Holen, Milde, Bomyea and Thorp2014). Whilst this does not diminish CBT's robust empirical evidence base to treat a number of psychological disorders, it should not be assumed that the same treatment outcomes can be generalized to refugee populations including survivors of torture (Neuner et al., Reference Neuner, Schauer, Roth and Elbert2002; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Halpern, Ferenschak, Gillihan and Foa2010). Therefore, in the absence of robust current empirical research the role of reflective practice can play a vital role in assisting to enhance effective clinical practice, manage therapist experiences and process therapy challenges which may arise when working with populations who may present with an increased level of complexity.

Research in the area of reflective practice including SP/SR in the last decade has increased significantly (Bennet-Levy and Padesky, Reference Bennett-Levy and Padesky2014; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015). Reflective practice, however, should not be a process which is limited to therapists who work with diverse groups, as the benefits of reflective practice are universal to all clinical practice. Whilst the critical incident analysis model is not widely used in the field of CBT practice, it is used in other fields such as social work and psychology (Lister and Crisp, Reference Lister and Crisp2007), but this does not necessarily reduce its utility as a tool to aid reflective practice within CBT.

Reflective practice particularly when used within contexts such as clinical supervision can encourage learning and assist to enhance therapist clinical skills. The critical incident analysis model can be used as a process to encourage reflection of both clinical practice and the assimilation of evidence-based research. The learning if implemented can positively improve clinical practice (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Haarhoff and Thwaites, Reference Haarhoff and Thwaites2015) and assist to improve the clients’ experience of CBT therapy.

Further research

Further research is required to help develop an analysis of the impact of reflective practice to include self-practice and self-reflective practice on treatment outcomes and skills development in CBT clinical practice.

Main points

(1) This paper contributes towards identifying some of the complexity which refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture can present with in brief therapy. Such complexity may include language barriers, an increased prevalence of PTSD and comorbid mental health problems in refugee populations.

(2) An increased risk of burn-out and vicarious trauma for therapists who process trauma including CBT therapists was highlighted in this paper.

(3) The paper identified that there is a dearth of current empirical evidence which evidences CBT's efficacy with refugee populations and survivors of torture and further research is required of how best to treat refugee populations in brief therapy contexts such as IAPT.

(4) The paper identified that effective reflective practice including the use of the critical incident analysis model and self-practice can assist to manage the possible challenges identified when working with refugee populations and improve the clinical practice of the CBT therapist.

(5) The paper also identified the important role of clinical supervision for IAPT CBT therapists and how reflective practice, when used within the context of clinical supervision, can assist to improve clinical practice particularly when working with diverse populations.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr Andrew Beck for his overview of this paper.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical statement

The author has abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Learning objectives

(1) Identify some of the challenges that refugees, asylum seekers and survivors of torture may present with during therapy.

(2) Explore how reflective practice can improve clinical practice particularly when working with refugee populations.

(3) Explore how the use of the critical incident analysis model and clinical supervision can assist to develop reflective practice skills and improve the clinical practice of IAPT CBT therapists who work with diverse populations.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.