Introduction: Gendered Mobilities

In her report for the World Bank, Tanya Priya Uteng (Reference Uteng2012: 4) stated that “Gender based variations of daily mobility is an established phenomenon in both the developed and developing parts of the world.” Although it is obviously not possible to generalize for all women in every location, in most instances such variations are the product of a range of constraints faced by women in contemporary society, and can produce inequality, disadvantage, and social exclusion (Bates Reference Bates2014; Grieco and McQuaid Reference Grieco and McQuaid2012; Scholten et al. Reference Scholten, Friberg and Sandén2012; Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist Reference Siren and Hakamies-Blomqvist2006; Uteng Reference Uteng2009; Uteng and Cresswell Reference Uteng and Cresswell2008). Robin Law (Reference Law1999) provides a nuanced critical review of contemporary literature on women’s mobility and access to transport, and identifies five key factors that, she argues, structure female mobility and should inform both theory and practice in mobility research. These focus on the role of gendered activity patterns, with women and men undertaking different roles within the household and in wider society; on the impact of gendered access to resources, with women usually earning less than men and often having poorer access to the fastest and most convenient forms of transport; on what she calls the gendered experience of embodiment as male and female bodies are perceived and treated in different ways in the public sphere; on the implications of gendered meanings attached to mobility practices where the same behavior by a man and a woman may be viewed differently; and through the subtle influences of a gendered environment where all actions and practices—including everyday travel—are constructed through a gendered lens. This theoretical framework, and the consequential impact of such structures on female mobility are likely to have been at least as significant in the past as in the present, but very little historical research has focused explicitly on gendered mobility. Where historical references are made in mobility research, all too often they have been highly generalized and rarely tend to go beyond broad assertions about constraints on female travel (Solnit Reference Solnit2001: 232–48; Urry Reference Urry2007). In this article we utilize some of the concepts identified by Law to examine in detail the varied mobility experiences of nine young female diarists who lived in Britain at various times from the 1880s to the 1950s.

Extant historical mobility research suggests that although women certainly experienced travel differently from men in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it did not prevent them from walking, cycling, and using the public transport that was available at the time. For instance, Barbara Schmucki (Reference Schmucki2012a) has used photographic and archival evidence to examine the presence of women in public spaces and on transport in twentieth-century Britain. She emphasizes the previous neglect of this topic, the widespread presence of women traveling, and the ways in which women shaped their mobility practices to accommodate the constraints and discomforts that they faced. Other works on everyday leisure activities, although not specifically focused on travel, highlight the extent to which women were visible in public places in the nineteenth-century city (Birchall Reference Birchall2006; Davies Reference Davies1992; Sleight Reference Sleight2013). Robin Law’s (Reference Law2002) study of gendered mobility in twentieth-century Dunedin (New Zealand) also highlights the ways in which being female structured everyday travel, without preventing women from moving around the city to fulfil their daily commitments. She uses oral history both to demonstrate the extent and nature of female mobility, and to explore the varied ways in which the different meanings attached to gender interacted with daily mobility for the “New Woman” of the early twentieth century (Marks Reference Marks1990; Roberts Reference Roberts2017). It has also been argued that in the early days of motoring when car ownership and use were confined to the wealthy elite, some women from such families were able to take advantage of the freedom offered by the motor car (Clarsen Reference Clarsen2008; Jeremiah Reference Jeremiah2007; Merriman Reference Merriman2012).

Initially the expansion of motor vehicle ownership to a wider section of society in the second half of the twentieth century was largely a male preserve, with the majority of women continuing to travel mostly on foot or on public transport. If they traveled by car, it was usually as a passenger. As male travelers increasingly hid themselves within motor vehicles, most women continued to be visible on the street and on public transport. However, the increased presence of motor vehicles on the streets did have a profound effect on women travelers. All those who did not own or have access to a car (not only women but also children, the elderly, and many with limited resources) were increasingly corralled into limited pavement space, and forced to endure the noise, pollution, and danger imposed by motor vehicles, while public transport became increasingly viewed as an inferior form of transport (Norton Reference Norton2007, Reference Norton2011; Schmucki Reference Schmucki2012b). Automobility, at least initially, had differential negative effects on many women compared to their male counterparts.

The concept of “separate spheres” has been an influential theme in much historical research and writing on gender. Though focused originally on the domestic sphere and the world of work, especially through Davidoff and Hall’s (Reference Davidoff and Hall1987) influential research on middle-class households in late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century Britain, the concept has been extended to include many aspects of spatial activity, with the implicit assumption that men and women lived distinctly different lives, including how they traveled and used public space (Hamlett Reference Hamlett2015; Morgan Reference Morgan2007). Over the past three decades the concept has been further expanded and critiqued (Gleadle Reference Gleadle2007; Kerber Reference Kerber1988; Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker1998; Vickery Reference Vickery1993), with recognition not only of the complex ways in which the lives of men and women intertwined in most aspects of everyday life but also of the fluidity of gender as binary definitions of masculinity and femininity have been increasingly viewed as oversimplified constructions of a complex reality (Davis Reference Davis2009; Fontanella et al. Reference Fontanella, Maretti and Sarra2014; Parker Reference Parker and Moran2016). There is no reason to assume that the complexities obvious today were not present in the past, even if they were more hidden from view (Connell Reference Connell1993, Reference Connell2005; Tosh Reference Tosh1999, Reference Tosh, Arnold and Brady2011). Therefore, there is evidence both for the widespread presence of men and women on the streets of nineteenth- and twentieth-century cities, and for their physical separation and distinctly different experiences of travel. In this article we approach the question through the words of nine young female travelers who lived in Britain in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Using diary evidence we examine the extent and nature of their mobility and, in particular, focus on variations that existed between social classes and different locations to try to uncover some of the complexities of female mobility experiences in the past. Personal testimonies from the past have rarely been used in this way, and these detailed individual perspectives can provide new insights to the nature, extent, and variability of female mobility in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Sources of Evidence

One reason for the limited historical research on everyday mobility is the lack of readily available source material. Obviously oral evidence can only be used for the recent past, and is dependent on the memory of the informant (Perks Reference Perks1995; Ritchie Reference Ritchie2015; Thompson Reference Thompson2017), while photographic evidence is manipulated by the photographer’s choices of time and location (Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1986; Prosser Reference Prosser1998). Although there were female authors in this period, published writing was predominantly produced by men and thus provides a largely masculine view of the experience of travel. Too often the experiences of women are obscured in the historical record (Hall Reference Hall1992; Sanday Reference Sanday1981). In this article we utilize the words of women as expressed in their unpublished personal diaries. Although not without problems of representation and interpretation, these allow us to get closer to the daily experiences of women than is possible with most other sources. Nine diaries are used in this research, all written by young unmarried women who lived in Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Only unmarried women of about the same age have been selected for easier comparability. Also, from a practical perspective, far more diaries survive for young unmarried women than for those who were older and had family responsibilities. Further details about the diarists are given in the next section of the article.Footnote 1

Diaries, autobiographies, and other forms of life writing have been widely used in historical research and the limitations of such sources are well known. Autobiographies and life histories have been most widely used, partly because they are more likely to have been published and are thus readily accessible (Delap Reference Delap2011; Falke Reference Falke2013; Griffin Reference Griffin2013; Humphries Reference Humphries2010; Steedman Reference Steedman2013; Vincent Reference Vincent1982). However, life histories that were written from the perspective of later life tend to sketch the broad structure of personal experiences rather than revealing the minutiae of activities such as everyday travel. Diaries written up on an almost daily basis are much more likely to have recorded everyday experiences and immediate reactions. Autobiographies were also most frequently written by men, whereas diaries were kept by both men and women but with a bias toward diary writing by younger women (Hewitt Reference Hewitt and Amigoni2006; Hogan Reference Hogan1991; Naussbaum Reference Nussbaum, Naussbaum and Olney1988; Sherman Reference Sherman and Richetti2005). Extant diaries should never be seen as a representative sample of female experiences: they were written by those with the education, resources, and time to keep a diary, and their survival is sporadic. Few genuinely working-class diaries survive. We also do not know what diarists chose to exclude from their accounts of daily life, and it is likely that routine events were less often recorded than those that were in some way unusual. There is thus a danger that accounts of everyday travel are biased toward rare occurrences rather than the mundane. Some prominent figures clearly wrote diaries with a view to future publication, and in these cases it is possible that that the diarist’s words were framed in ways that projected an image that was designed for later public consumption (Fothergill Reference Fothergill1974; Lejeune Reference Lejeune2009; Ponsonby Reference Ponsonby1923; Vickery Reference Vickery1998). In this article we use only diaries that were written by women with no public profile and, as far as we can tell, with no expectation of publication. Although some diarists did write for an audience of family and friends (Hunter Reference Hunter1992; Rogers Reference Rogers1995; Steinitz Reference Steinitz2011), most of the diaries we have read are clearly labeled “private” and are likely to have been kept hidden from others. Eight of the nine diaries are unpublished and are lodged in a public archive (Bishopsgate Institute Archive, London); the ninth was given to the authors (with permission to use) by a descendant of the diarist and has since been published (Pooley et al. Reference Pooley, Pooley and Lawton2010). The diaries used in this article were selected from those available to reflect a range of locations, circumstances, and periods. We have deliberately chosen to examine diaries drawn from a long period to assess how mobility for these individuals changed in relation to substantially altered economic, social, and cultural norms and transport options.

The Diarists

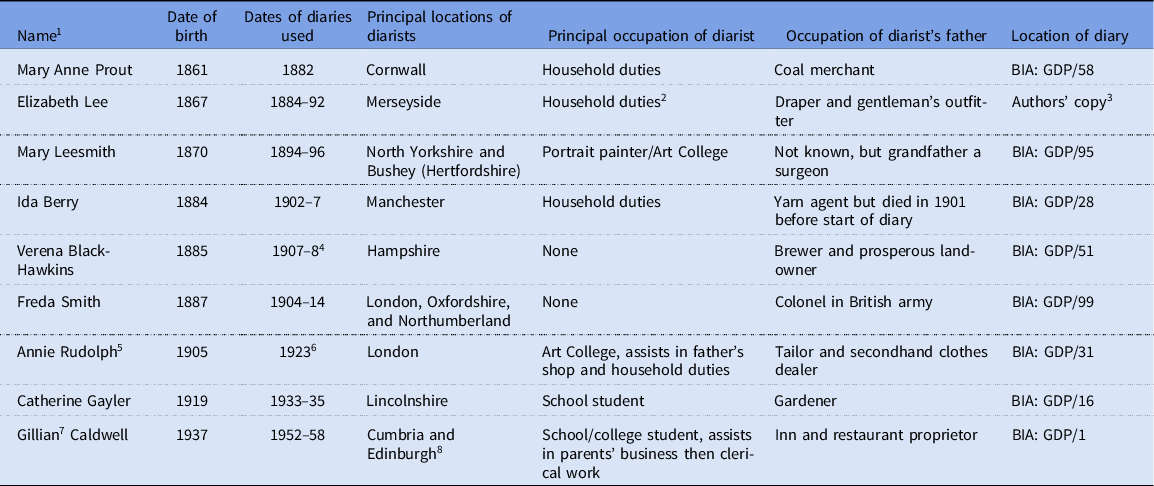

Brief details of the diarists studied are provided in table 1. All were born between 1861 and 1937, with surviving diaries covering the period 1882 to 1958. Seven of the diarists lived in various parts of England throughout the period of their diary, but one also spent some time living in Scotland and in Switzerland and another a brief period in Germany. Within England, most regions are represented at least briefly, and with a mixture of urban and rural locations. Seven of the nine women were unmarried throughout their diaries; for the other two diarists we use only those portions of the diaries written before they were married. Social class is hard to define for young unmarried women, most of whom did not have a paid occupation. Five of the young women were students for part of the diary, most undertook some unpaid household duties, and four had some form of mainly part-time employment, two of which were in a family business and were not necessarily paid. The occupations of the young women’s fathers arguably provide a clearer guide to the social position of the family. Based on this information two could be classed as elite (Black-Hawkins and Smith), two upper-middle class (Lee and Leesmith), four as lower-middle class (Prout, Berry, Rudolph, Caldwell), and one as working class (Gayler). Three diarists lived in lone-parent homes: two of the diarists were without a father throughout their diary (Leesmith, Berry) and one lost her mother during the course of the account (Rudolph).

Table 1. Brief details of the diaries studied

Source: Bishopsgate Institute Archive (BIA), London.

1 All names are maiden names.

2 Also occasional help in father’s shop.

3 Published as Pooley, C., S. Pooley, and R. Lawton (2010) Growing Up on Merseyside in the Late-Nineteenth Century: The Diary of Elizabeth Lee. Liverpool University Press.

4 The diary continues until 1939 but in this article we use only the portion 1907–8 during which the diarist is unmarried.

5 Also Rudoff or Rudolf.

6 The diary continues with very sparse entries of major events only to 1983.

7 Anne Gillian Mary; usually calls herself Gill or Jill.

8 Also a brief stay in Zurich not covered in this article.

Mary Anne Prout was born in a small village in Cornwall in 1861 and lived there with her parents throughout the course of her diary. Her father was a coal merchant who traded coastally out of the port of Perranporth, close to where they lived in the village of St. Agnes, and Mary Anne (age 21 during the diary) had no obvious employment other than helping in the house. At the time of the 1881 census Mary Anne shared her home with her parents, younger brother, a niece of about the same age as herself, two visitors, and a boarder, all of whom had been born locally. She married a local man two years later. Elizabeth Lee was born six years later in Birkenhead (Cheshire).Footnote 2 She kept her detailed diary for 8 years from the age of 17, during which time she lived with her parents, eight brothers, and one servant in a large house in Prenton,Footnote 3 a suburban village on the edge of Birkenhead. Her father was joint proprietor of a gentlemen’s outfitters in Birkenhead and a prosperous and respected Birkenhead citizen. Elizabeth assisted in the shop from time to time but otherwise was engaged in household duties. Unlike Mary Anne Prout whose nearest urban center was the small town of Truro,Footnote 4 Elizabeth had easy access not only to the rapidly growing town of Birkenhead but also across the river Mersey to the city of Liverpool.Footnote 5 Mary Leesmith was born near Malton, Yorkshire, in 1870 and kept a (surviving) diary for two years from 1894. At the start of the diary she and her mother were living near the market town of Ripon (Yorkshire) with Mary’s aunt, but at the end of the year they returned to their own home in Bushey (Hertfordshire), some 16 miles (25 km) from central London.Footnote 6 Mary Leesmith was an art student and portrait painter with her own small studio and some commissions, mostly to paint portraits of family friends. There is no mention of her father in the diary or in any census record, and in 1871 (when Mary was less than 1 year old) she and her mother (recorded as married) were living with her mother’s parents and their three servants near Malton, Yorkshire. Her grandfather was a surgeon and the Lascelles family was clearly reasonably well off.Footnote 7

Three of the diarists studied were born within 4 years of each other in the 1880s. Ida Berry’s diary runs from 1902 to 1907 when she was aged 18–23. Born in Eccles (Manchester), at the time of the diary she was living a short distance away in Withington with her widowed mother and two younger sisters. Her father had been a yarn agent and had died in July 1901, some 15 months before the start of the diary. Ida had no paid employment and her mother was described in the census as living on her own means. The family was not poor but at times money was limited. In contrast, Verena Black-Hawkins came from a wealthy family. Born in Newbury (Berkshire) in 1885, she started her diary in 1907 at the age of 22 and it continued until 1939, although in this article we only utilize the first 16 months of the document before she was married. At the start of the diary Verena was recovering from tuberculosis at a clinic in Germany, but 4 months later she returned to the United Kingdom to live with her parents in a small village near Andover, Hampshire. Verena had no paid occupation but her father came from a prosperous brewing family and he owned a substantial estate in Hampshire. During the early part of the diary she spent quite a great deal of time in London visiting her fiancé. Winifreda (Freda) Smith, born in 1887 on the Isle of Wight (Hampshire), also came from a wealthy and well-connected family. Her father was a colonel in the British army; she was presented at court and was related to aristocracy.Footnote 8 At the start of the diary Freda was still at boarding school, and she had no paid occupation during the course of the diary. Her father was often posted abroad and Freda was quite peripatetic. She mostly lived with her parents in a smart central London house, but also stayed with other London relatives, with her maternal grandmother on a large estate in Oxfordshire, and with her Watson-Armstrong relatives at Cragside and Bamburgh, Northumberland. Her diary runs to 1914.

The final three diarists were born in the twentieth century and all come from more humble backgrounds. Annie RudolphFootnote 9 was born in London in 1905 and kept a detailed diary during 1923 when she was 17.Footnote 10 Her parents were Jewish emigrants from Russian Poland and had arrived in Britain between 1900 and 1904. Annie’s father was described in the 1911 census as a tailor and secondhand clothing dealer, and initially they lived above the shop in London’s East End. However, by the time of the diary they had moved some 5 kilometers to a house in north London and had let the flat above the shop to tenants. Annie had nine siblings (Annie was the third oldest), and at the age of 17 she worked part-time in her father’s shop and also studied part-time at art college, focusing on fashion and design. Annie’s life was severely disrupted in May 1923 when her mother died suddenly. As the eldest daughter at home Annie had to take on full responsibility for the home and her younger siblings while continuing to work in the shop and to study. This was a period of considerable hardship for Annie and her family. Catherine Gayler was born in 1919 and was just 14 years old when she began her diary in 1933. The diary lasts for 2 years during which time Catherine was a school student. Her home was in a small village some 6 miles (10 km) from the market town of Grantham (Lincolnshire), which was where Catherine went to school. The 1939 registerFootnote 11 described her father as a “Head gardener, heavy worker” and he was most probably employed on a nearby large estate. Although the family was by no means affluent, Catherine almost certainly attended the local selective grammar school and it can be suggested that they may have had middle-class aspirations. In 1939 Catherine was living in Nottingham and was working as a civil servant. The final diarist studied is Gillian Caldwell. Born in 1937 in Stockport (near Manchester), she kept a diary from 1952 to 1958 and lived in the most remote location of all the women studied. Her father ran an inn and restaurant in Eskdale, Cumberland,Footnote 12 in the English Lake District, and her nearest town of any size was Whitehaven, some 18 miles (28 km) away. At the start of the diary she was at a local girls’ private boarding school,Footnote 13 but in 1954 when she had left school she worked for a few months at a travel agency in Zurich, Switzerland, and after that did clerical work in Edinburgh. She had aspirations to go to university but never fulfilled them. Although these nine young women lived very different lives, they all traveled regularly as part of their everyday activity. It is this mobility that we now examine in detail, by providing first a brief overview and then detailed examples from the diaries.

Intersecting Mobilities: Place, Time, Class, and Culture

All the young women studied traveled frequently, mostly within their local areas but some over much longer distances. They used a wide range of the transport modes available at the time, traveled both alone and with others, at most times of day, and recorded relatively few constraints and inconveniences. Overall they were a highly mobile group of young women, as exemplified by the diary extracts given later in this section. Many factors can interact to construct particular mobility opportunities and experiences for individual travelers (Cresswell Reference Cresswell2006; Merriman Reference Merriman2012). This makes generalization difficult: the mobility profiles of different women must be related to their personal circumstances and situations. Time is probably the most straightforward factor. For the most part, young women gained more freedom and flexibility in how they traveled as they moved from their young teenage years to greater independence as a young adult; and as new transport modes became available and, crucially, more accessible, the ways in which people traveled also changed (Dyos and Aldcroft Reference Dyos and Aldcroft1969; Freeman and Aldcroft Reference Freeman and Aldcroft1991). However, as demonstrated in the following text, even these trajectories can be complex. Location is also important, particularly the difference between rural areas with generally poor transport provision compared to larger urban areas, but location can also be significant in other ways if, for instance, expectations and norms of behavior differed between places. Thus parameters constructed by class and culture could influence how young women traveled and could interact with the influences of both time and place. Some of these themes are now explored, using examples from the nine diaries selected for study to compare the differing mobility experiences of women who lived in Britain. We structure this section by period as this ensures that the transport available was broadly similar, and it also allows more effective exploration of the intersections of class, culture, and place within a particular period. These themes are also reexamined in the conclusion in the context of the framework discussed in the introduction.

Mobility in the Late Nineteenth Century

The diaries of Prout, Lee, and Leesmith were all written during the last 20 years of the nineteenth century, but the nature of their travel varied markedly depending on where they lived. In rural Cornwall Mary Anne Prout rarely traveled far, but she moved freely around the immediate locality often on foot but sometimes by wagon or other horse-drawn vehicle. The nearest railway station was some 5 miles (8 km) from her home, but during the course of the diary she recorded no instances of traveling by rail. Several visitors did arrive by train and most frequently walked from and to the station. The following two extracts are typical of her mobility:

I walked over to Perran this afternoon to see Father he told me to wait for him. I staid there until nearly 10 o’clock and then walked home by myself. (Prout 1882: Thursday, May 4)

Mrs Piddlestone, Mrs Henwood, Miss Piddlestone, Miss Bessie Henwood Mother and me went into Truro this afternoon in Hancock’s Wagonette. (ibid.: Sunday, May 7)

In contrast Elizabeth Lee had access to a much wider range of transport options on Merseyside. She walked both alone and with friends (as did Mary Anne Prout), but also traveled by tram, rail, ferry across the river Mersey, hansom cab, and (occasionally) in her family’s small private carriage (trap or “dog cart” which she only recorded once as driving herself).Footnote 14 These differences between the diarists reflected both the transport opportunities available where they lived and also differences in wealth and class. When Mary Anne Prout traveled in a horse-drawn vehicle, it was usually with others in a bus, waggonette, or carter’s wagon, whereas when Elizabeth drove it was in her father’s horse and trap, although she also used a full range of public transport in Birkenhead and Liverpool. Two examples from Elizabeth Lee’s diary are typical of her daily travel:

I went down to the shop tonight to help them in serving. Mrs. Hope was there. I came home by myself in the tram, as Papa was not coming till later. (Lee 1884: Saturday, May 17)

Tonight “Mr. Bragg” took me to a ball at the City Hall, Liverpool. Mr. Rimmington took Miss Homes. Of course we all went together. Enjoyed myself immensely. We caught the 4.a.m. boat and came home (all the lot of us) in a hansom (which is only made for two). (ibid, 1888.: Tuesday, April 27)

Mary Leesmith’s family was also relatively affluent and when staying with her aunt in rural Yorkshire she had access to the family’s private carriage with coachman, but she also walked and traveled by train, both alone and with family and friends. However, when in London she and her mother did not appear to have their own carriage, and travel was entirely on foot, by hansom cab, or by other public transport, utilizing the full capabilities of the expanding rail (overground and underground), tram, and bus networks in and around London (López Galviz Reference López Galviz2019). Again she frequently traveled alone as well as with companions, but moving to a more urban environment greatly widened her mobility options. Two examples are typical of her movement, the first in Yorkshire and the second in London.

Dressed and drove up to the Mechanics Institute with A.F. … just in time to hear the Dean open the Bazaar in the place of Lord Ripon. … as AF and I were getting some tea the carriage came for us so we drove home still pouring rain & spent the evening at Sunnybank. (Leesmith 1894: Wednesday, November 7)

Hs & I went to town at 9.12, lovely morning—changed at Willesden, Addison & Gloucester Rd for Bayswater. Went to Whitley’s to see if they let out costumes—recommended us to Covent Garden shops. Got a map & then armed with that we went by bus to Bond St, walked down there looked at some photos, had lunch at Lyons. Then went up and down Endell St, found no shops we wanted, then went down Bow St., went into 2 shops there. … Then to Holborn Rest for something to eat. Wired mother we couldn’t get home till 9. Back to Burnets where we got all we wanted in scraps (some lovely remnants) and then home after a long day. (ibid. 1895: Friday, January 18)

Mobility in the Early Twentieth Century

Berry, Black-Hawkins, and Smith all kept diaries during the first two decades of the twentieth century when mobility options expanded due to the increased availability of bicycles and the development of motorized transport in the form of both private cars and motor buses (Dyos and Aldcroft Reference Dyos and Aldcroft1969; Horton et al. Reference Horton, Rosen and Cox2007; Mom Reference Mom2014; Pooley et al. Reference Pooley, Turnbull and Adams2005). The three diaries do show some engagement with new forms of transport but also much reliance on more traditional means of mobility. As in the earlier period, there were also significant differences in mobility practices depending on location. In south Manchester Ida Berry used a wide range of different transport modes to move freely around the city, often combining walking with a variety of forms of public transport (trains, trams, buses, and cabs). She was an enthusiastic cyclist (usually with her sister) but her bicycle was used almost entirely for leisure purposes (Jungnickel Reference Jungnickel2015). She recorded no instances of traveling in a motor car and her mobility varied little over the course of the diary. In contrast, Verena Black-Hawkins had very different mobility options depending on whether she was in Hampshire or London. At home with her parents she mostly walked locally or “drove” in the family’s carriage, but when in London she made greater use of public transport including the underground. Longer-distance travel was mostly by train, and before she was married the only mentions of “motoring” were when she was staying with friends in Kent.Footnote 15 The following brief extracts from these two diaries are typical of the nature and range of mobility experienced by these two young women. They used whatever forms of transport were available to them in a particular location, traveled both alone and with friends or family, and recorded few restrictions or significant inconveniences.

In the evening Maud and I went for a ride through Gatley and Cheadle, and had a lovely coast down Schools Hill. We saw Chris at Didsbury. (Berry 1903: Tuesday, July 28)

We went to Chapel and then for a walk with Ruby and Norman and they brought us home. After dinner they called for us and we went on the bus to Cheadle and then on a tram to Stockport and then another to “Woodley”, and on the way we passed “Vernon Park”. We climbed 700 feet and got to the top of “Werneth Low”. It was lovely all the country round and we could see “Kinder Scout” in the distance. We had tea at “Compstall” and then walked into “Marple” it was a lovely outing and we did enjoy it. We came home by train from Marple and they brought us home. (ibid. 1904: Friday, April 1)Footnote 16

Mr Firebrace motored us over to a garden party. (Black-Hawkins 1907: Tuesday, June 25)

Came up by an early train. Shopped with Mrs P and drove in the afternoon. (ibid.: Monday, July 8)

Walked with Sommy to Knightsbridge, tubed to no. 23 and then walked to the stores with Cecil, and bused home. (ibid. 1908: Friday, January 10)

Freda Smith also traveled widely and spent time during her diary in several different locations in Britain, together with periods traveling abroad with her family. For most long journeys between different parts of the country, Freda traveled by train as the very extensive rail network at the beginning of the twentieth century permitted complex journeys both between and within rural areas as well as between larger settlements (Simmons Reference Simmons1986; Turnock Reference Turnock1998). Although in 1906 her father was only contemplating buying a car himself (Smith 1906: Saturday, November 17) he had access to army cars through his work, and at least three other relatives and a number of family friends owned motor cars; thus Freda often traveled by car for distances of up to 40 miles (64 km), although breakdowns were a frequent inconvenience (O’Connell Reference O’Connell1998; Pearce Reference Pearce2016).

As was the case with other diarists, Freda’s mode of shorter-distance travel varied considerably with location. In London most shorter-distance journeys were undertaken on foot, by private carriage, or in relatives’ cars, although her diary mentions occasional use of hansom cabs, motor taxis, buses, and London Underground trains. With fewer public transport options in rural Oxfordshire, Freda traveled to visit friends or to access amenities in nearby villages on foot, by bicycle, or in her grandmother’s private carriage or other relatives’ cars. She bought a new bicycle in London but apparently never rode it there; however, in Oxfordshire she and one of her aunts made some quite long excursions by bicycle in addition to shorter, more utilitarian journeys. In contrast, on visits to rural Northumberland there is no record of bicycle use: apart from local walks, almost all journeys were in motor cars that belonged either to her Watson-Armstrong relatives or to their other guests. Motor transport belonging to fellow (mostly young male) guests was also the predominant form of transport used by Freda and her friends at weekend country house parties in other parts of the country, and on one such occasion in 1907 she records having a driving lesson herself (ibid. 1907: Monday, August 5).Footnote 17 The brief extracts from her diaries before 1909 given in the following text are typical of Freda’s travel during that period.

Cragside [Northumberland]. Left London by 10 train with father. All the country white [with snow] … We had a 2 hrs wait [at Newcastle] as motoring out was impossible. Came by last train full of doubt whether we shd. get through the snow but we did! (ibid. 1906: Thursday, December 27)

[London] This morning to Miss Sutcliffe [dressmaker] in a hansom … lunched at 92. Afterwards M[other] and I had the carriage and left cards on a great many people. (ibid.: Friday, May 25)

[London] M[other] and I went by the new tube [Piccadilly line opened December 1906]—to Regent and Bond St. Ball dress hunting etc. Afternoon I went to Sutcliffe with Reid [servant] who was very disagreeable- and is going - thank goodness. (ibid.: Monday, December 17)

[Britwell, Oxfordshire] Afternoon drove to Watlington with A[unt] A. and Mother … Tuesday 3rd …To post this morning. Afternoon A[unt] G. & I bicycled to Ewelme. (ibid. 1905: Monday, October 2; Tuesday, October 3)

[Neasham Hall, Darlington] Hope and Guy W, Miss le P., William Cox & I motored off to Harrogate in his car (Wm. Cox’s) a perfect Siddeley. I never had such a ripping run … 30 in abt. 1 1/4 hrs. Tea at the Majestic. Left H. 6.30 home at 8. (ibid. 1907: Sunday, August 10)

[Durrington, Wiltshire] Started off abt 9 in the car, with Grayling, to catch 10.9 [train] from Salisbury. Very cold. Car broke down in the moor. We waited 1½ hrs. Pressing wind! Then walked in to Amesbury & I caught 12.15 up, changing. M[other] wd. not have minded my coming up with Capt Hill. Got home abt 3. (ibid.: Monday, March 11)

It is noticeable that in most of the extracts above Freda rarely traveled alone; in her early diaries she specifically notes occasions when she was allowed out alone. In contrast to all the other female diarists she appears to have been more restricted in her daily mobility as the social position of her family, and perhaps most importantly Edwardian elite societal norms, led to her being chaperoned on many trips by family members, by contemporaries (usually female) known to her family, or by servants; this was particularly the case before she was 20 years old (Dyhouse Reference Dyhouse2013). However, the extent to which this occurred did vary, partly depending upon her location at the time. Most restrictions applied when she lived in London or was staying with her paternal grandmother in Oxfordshire, but there were far fewer when she stayed with her aunt, Baroness Winifreda Watson-Armstrong, in northeast England, despite that family being of higher social status than Freda’s parents. Freda also had more freedom when at country house parties where the guests were socially selected and therefore presumed to behave appropriately. As she grew older, she became more astute at negotiating and obtaining more freedom, for which she was obviously grateful. The following extracts illustrate the variations by location and age in the extent of Freda’s chaperoning.

[London; aged 20] M[other] tells me she is told “young C [Freda’s dentist] … is a bad lot” & I am not to go alone any more. It seems absurd. (ibid.: Wednesday, May 15)

[London; aged 19] This mng I went to Harrods and Sloane Street shopping alone!- Xmas things. (ibid. 1906: Wednesday, December 12)

[London; aged 20] M[other] was very good & let me go with John to the Stores etc. He is so nice … [He]had to leave for the 2.35 train- they [John’s family] have asked me down to Brightwell for Sunday - Father will not let me go this time - I am awfully disappointed. (ibid. 1907: Tuesday, July 2)Footnote 18

[Bamburgh, Northumberland; aged 17] Walked with Guy to golf. … Evening walked home with Guy via P.O & seat. After dinner loose boxes for some time. (ibid. 1904: Monday, September 19)

[Cragside, Northumberland; aged 20] … Jack goes by train tomorrow so we made the most of today! … This evg song followed song. At last we got so desperate that Jack went and asked A[unt] Winy if we could go out. She said ‘certainly’. She was altogether a brick. All the other relations - and there were tons of them - at least it seemed so - looked horrified. She was ripping. Out there it was so nice … I hope Granny won’t give me away. (ibid. 1907: Monday, August 26)

[London; aged 20] This aft to Sloane St … It is so nice being able to get out without a maid more. (ibid.: Wednesday, October 23)

[London; aged 20] I went to the Oratory this afternoon. Coming out I met Mr Howard Wilson and rather against my will, he walked me home. He is an odd man. I never feel quite sane with him. M[other] did not mind his walking home with me. (ibid.: Sunday, November 24)

Mobility in the Mid-twentieth Century

The diaries of the final three women span a much longer period of more than 30 years. This was in theory a time of rapid change in mobility behavior as motor cars and bicycles in particular became increasingly available, although even in 1951 only 14 percent of British households had access to a private motor vehicle (Department for Transport 2016; Gunn Reference Gunn2013). As in the earlier periods, location played an important part in determining mobility options, but this also interacted with both the social position and culture of the families concerned and, to a degree, with the social and economic mores of the time. Annie Rudolph lived in London and, like the earlier diarists who lived in or near the capital, had all the benefits of London’s extensive transport networks (Barker and Robbins Reference Barker and Robbins1963). She traveled frequently and freely on foot, by bus, tram, and train, with occasional rides in a taxi; she did not have access to a private motor vehicle and made no mention of cycling. She both traveled alone and with others and moved around the city at most times of the day and night. In contrast, Catherine Gayler, writing some 10 years later, lived in a rural location and had much more restricted transport options. She walked and cycled locally, and routinely used the bus to travel to her nearest town. Even though there was a station nearby, she made only occasional mention of travel by train. However, although Catherine’s mobility options were more restricted than those of Annie Rudolph who was 4 years her senior, there was little apparent difference in the frequency and freedom of their mobility. Both young women fully utilized the mobility options open to them. Gillian Caldwell began her diary almost 30 years after Annie Rudolph, arguably when British society was changing rapidly (Brooke Reference Brooke2001; Marwick Reference Marwick2003; Thomas Reference Thomas2008; Tinkler et al. Reference Tinkler, Spencer and Langhamer2017; Todd Reference Todd2005), but in many respects her everyday mobility mirrored that of young women in earlier generations. Initially her remote rural location in the English Lake District restricted how she traveled but, like Annie in London, her everyday travel options widened when she was in Edinburgh. However, as was the case with her predecessors, in both locations everyday travel was mainly on foot and by bus or, in the city of Edinburgh, by tram. In both locations longer journeys were mostly by train, although when in Eskdale it would have taken her at least 40 minutes to travel by car from her home to the nearest mainline railway station. Her father did own a car, as did several of her male friends, and she often relied on lifts to undertake journeys both for leisure and to and from her nearest urban centers. Journeys were often problematic with missed connections and appointments. She also owned a bicycle but in Eskdale rode reluctantly, possibly discouraged by the very hilly environment in which she lived. There was no mention at all of a bicycle in Edinburgh, and car travel in the city only occurred when she had a boyfriend or other acquaintance with access to a vehicle. The following quotes from the diaries provide typical examples of the everyday travel of these three young women.

I have just got home—nearly 12! Am waiting for supper and am writing while I am waiting. Betty and I went to meet Albert and Dave at the appointed place—only 5 minutes late. As it was early—6.30—we went for a bus ride up West. We went into the Alexandra Theatre first and booked seats. The show commenced at 9 so we had tons of time. We went up West and paraded around and got back to the theatre just 10 minutes before the show started. We felt so posh. (Rudolph 1923: Tuesday, March 27)

Had such a surprise yesterday—nearly knocked me over—I was on the [tram] car on the way to art class—I hopped on the car and squatted—when looking up I saw someone sitting next me who did seem familiar. … We started talking over old times and it was jolly—seeing an old friend again is always so nice. I told him I was going to classes so he said “Give it a miss”—and we got the bus and went up West. He wanted to go to a cinema. (ibid.: Wednesday, December 19)

Went up heath in morning. In afternoon hiked a little way past Hall. Went to Grantham on 4 o’clock bus with Mummy. Had a new coat, a dull red one. (Gayler 1934: Saturday, January 27)

Biked over to Grannies at night with Daddy. Saw Auntie Lucy and Auntie Mabel. Coming back at about 15 ½ m.p.h. (ibid.: Sunday, August 19)

Bus very crowded. Both boys and girls on one bus as other broke down at Frieston. Stayed to get hair done and came home on 5 bus. (ibid.: Friday, October 5)Footnote 19

I am a clot … reason, I missed the bus! Anyway Kurt took me to Gosforth where I caught it and flopped down beside Joe. I arranged to meet him at the Empire about five. (Caldwell 1952: Saturday, January 19)Footnote 20

The journey home was VILE, with an extra big capital V. I coughed solidly until Bentham and felt very embarrassed; goodness knows what it must have been like for the other people in the compartment. Me like a clot got off at Seascale station when Pops was at Drigg but as I said to him, how on earth was I meant to know to get off at Drigg when he wasn’t even visible on the platform. (ibid. 1953: Wednesday, April 8)Footnote 21

Pooh [female friend] and I were too damned broke to do anything tonight. So we took a tram out to Easter Rd and walked all along the Queen’s Mile and talked. The slums are quite amazing still. Then we came home by the castle and parted about 9.30 so we had an early night. (ibid. 1954: Tuesday, May 25)Footnote 22

One theme that does emerge quite strongly from these three accounts is the role of differences in culture and norms of behavior in shaping mobility. All three young women had considerable freedom to move around unhindered and often alone, though probably for reasons of convenience and sociability, the majority of everyday movements were with a companion of some kind. However, a change in personal circumstances could fundamentally affect these freedoms. For instance, Annie Rudolph’s family was Jewish, and after her mother died in May 1923 Annie’s life changed substantially. Not only did she have to take on additional domestic duties at home but also she was required to observe the Jewish practice of one year of mourning after the death of a parent. This meant that she should not engage in any amusement or entertainment although essential business and basic social engagements could continue.Footnote 23 The customs and norms of her family’s religion fundamentally changed Annie’s everyday activity patterns, and although she accepted these restrictions initially, her diary attests to the frustrations that this sometimes later caused:

I used to go out in the week ends and enjoy myself—theatre, dances, pictures—now I don’t go anywhere as I have to keep up a year’s mourning. I don’t really feel for going out—I don’t want to enjoy myself—who would believe that it is the same Me now … I am absolutely glad to stop in doors Saturday and Sunday for a rest! (Rudolph 1923: Wednesday, May 28)

I usually go to Milly’s place on Saturday. Sometimes I go to Belle’s place too. It passes an evening and I like to go there as it is a little brighter to home, and we talk over things. I don’t go out anywhere at all now—except there. Sometimes I go over the park. (ibid.: Saturday, September 13)

While Annie Rudolph was constrained by the norms of her religion after her mother’s death (though earlier in the diary she also complained about not being able to go out due to Passover), Gillian Caldwell’s mobility in Eskdale was affected very differently by the cultural environment in which she grew up. She lived in a pub/restaurant where there was an ample supply of alcohol and, apparently, very relaxed attitudes to drinking and driving. It was normal for her and (mostly male) friends to drive out somewhere with alcohol and clearly come back somewhat the worse for wear. She never came to harm but does record a number of serious road accidents that affected acquaintances in the locality. The following excursion was typical:

We weren’t very busy today and while the others went for a walk I ironed my dress (THE denim one) in case David should come. He didn’t come. So by the time we were all ready for Wastwater I subsided into misery! Three large gins perked me up so off we went—Humph driving the Daimler and me navigating. It looked perfect. The moon was full, the echo wonderful, and the booze quickly drunk! At 1.00 we went to Seascale and Humph finished off by carrying me up the beck to the car across the sands in the moonlight. Finally got home at 2.00 with a somewhat shaken, slumped Pooh [female friend]! (Caldwell 1954: Saturday, June 12)Footnote 24

While at times Annie Rudolph felt restricted by her family’s religious practices, most young women diarists (including Annie for much of her diary but possibly excluding Freda Smith) recorded few constraints that irritated them or prevented them from engaging in a wide range of social and other activities. This does not necessarily mean that limitations to their mobility did not exist—and we are all constrained in our actions to some extent—but it does suggest that those restrictions that were encountered were accepted as normal and were not worth recording in a diary. This theme is further explored in the text that follows.

Concluding Discussion

All mobility practices must be viewed within the context of the time and environment in which they took place. Opportunities for independent mobility almost always increase with age, are usually greater (and easier) in urban areas with good transport networks than in remote rural locations, and must be viewed within the context of the cultural norms of the individuals, families, communities, and societies in which they were situated. Thus it is not surprising that Gillian Caldwell in the 1950s had somewhat more freedom to travel than did Annie Prout in the 1860s—society, economy, and technologies were very different—but what is notable are the similarities between the mobility practices and experiences of all the diarists irrespective of their time or location. It is clearly not possible (or sensible) to seek to generalize unduly from only nine diaries: they are nine separate and very individual accounts and must be viewed as such. We have also not compared these diaries with those of young men living at the same time and in similar locations,Footnote 25 so it is hard to evaluate gender differences in mobility. However, what the diaries do show is that all these young women had substantial and varied mobility experiences, albeit situated within the specific contexts of their location, class, culture, and period. Many of the themes explored here are equally relevant for female mobility today, but detailed comparison is beyond the scope of this article.

We now return to the themes introduced at the start of the article and seek to assess the extent to which the factors identified by Robin Law (Reference Law1999) influenced the mobility of the nine young women studied. The different roles that women undertook within society clearly did influence everyday mobility. Apart from Gillian Caldwell in Edinburgh in the 1950s, none of the female diarists worked full-time and most had no paid employment. They all contributed to household chores to some degree (though not always willingly) and by definition thus spent more time in the home, while excursions beyond the home were mostly for social and recreational activities rather than for work. In these respects, male and female mobilities must have differed, though this does not mean that the young women did not have high levels of mobility within the framework of their lives. Gendered access to resources also clearly influenced the mobility recorded in the diary, although it did not necessarily restrict it or lead to large differences in how men and women traveled. Apart from when Gillian Caldwell worked in Edinburgh, the diarists had little independent income and relied on a parent (usually male) to provide money for travel. Even when working, Gillian was frequently short of cash and received financial help from her father when at home. Of course, it can be suggested that such financial dependence was (and still is) common for many young people, both male and female: but in most cases it continued much longer for women. To an extent income did affect the ways in which the diarists traveled: for instance, Freda Smith, who came from an affluent family, had more access to a motor vehicle in the early twentieth century than did Catherine Gayler, whose family was much more financially constrained but who was living some 20 years later. However, for most of the period studied men and women of all classes traveled by similar means; the main difference was that the rich were more likely to have access to a private carriage of some kind, though such transport was much more widely used in rural than in urban areas where all classes to some extent used public transport (including cabs, buses, trams, and trains).

Male and female bodies have always been viewed differently and the impact of the “male gaze” is something of which all women must have been as aware in the past as in the present (Calogero Reference Calogero2004; Simons Reference Simons1988). However, there is only limited evidence in the diaries that an awareness of what Law (Reference Law1999) terms the gendered experience of embodiment impacted significantly on the mobility decisions and experiences of the young women studied. A number of the diarists, especially Elizabeth Lee, Ida Berry, Freda Smith, Annie Rudolph, and Gillian Caldwell, frequently recorded travel and activities with mixed groups of young men and women. These were for the most part viewed as unproblematic although inevitably the diaries do not record the unspoken ways in which young women may have adjusted their behavior in response to male attention. Only Annie Rudolph in London explicitly recorded incidents where she was obviously aware of her vulnerability and/or was placed in a situation in which she felt uncomfortable because of a male presence. Two examples are given in the following text, but whether the fact that such incidents are not recorded in other diaries is because they did not exist in other times and places, or because only Annie chose to record them, is impossible to assess, although the increased freedoms and new fashions for women in the 1920s may have been significant.

Got to Liverpool St. at 12.45. Imagine me walking in the street at that time of night. The first time in my life—honestly. Everyone looked at me. Who was to know he was my brother with me? Walked to Shoreditch—Oh my feet! And was very fortunate to catch a stray bus that was out for an airing—after waiting half an hour! (Rudolph 1923: Sunday, April 13)

We were both togged up in the fashion then of very short skirts (about 2 years ago) and they barely covered our knees—but we wore nice stockings so we didn’t mind. Well we sat down and crossed our legs and started jawing. Suddenly along came two officers … well they chortled and came over—they looked at our legs so we quickly uncrossed them. They asked us what we were doing up there—so we said—same as you probably. So they told us we shouldn’t wear such short skirts … We don’t wear short skirts to entice them—only because they were fashionable. (ibid.: Saturday, September 27)Footnote 26

The preceding two quotes also exemplify the final points made by Law: that the same mobility behavior may be viewed differently when undertaken by men and women, and that all women existed in a gendered environment that constructed all aspects of their behavior, including everyday travel. Clearly, Annie was aware that walking late at night with a young man in central London could be viewed as behavior unbecoming a respectable young lady (even though on the occasion she noted the man she was with was her twin brother); and by wearing the fashions of the time she was equally aware that she attracted unwanted attention from men.Footnote 27 Other diarists never explicitly mentioned similarly uncomfortable or distressing incidents although some, including Elizabeth Lee in the 1880s, Freda Smith in the 1900s, and Gillian Caldwell in the 1950s, recorded in some detail how they flirted with many different men. It has been suggested that travel, on foot or by car, could give some women the freedom to engage in flirtatious behavior without being committed to anything more deep or meaningful (Pearce Reference Pearce2016, Reference Pearce2018). Three typical diary entries are given in the text that follows and at no time did these young women give any indication that the attention was unwanted or uncomfortable, but neither did they necessarily see it as anything too serious. However, in each case, mobility—on foot or by car—was central to the experiences recorded.

I went to L’pool this afternoon. Went a short walk with Mr. Williams tonight, then had him in the house. Had a good talk with him and we did have such a spoon. Did enjoy myself. It is such a time since we have had such a nice time together. I wish we could go on just the same, instead of him having to go away. (Lee 1888: Saturday, September 1)

Tonight we had a fancy dress dinner and danced afterwards. It was such fun. Jack was awfully nice. We flirted quite a lot! I know A. Winy does not really mind- It was fun. … Jack is nice- the most awful flirt. But we both know it is flirting. (Smith 1907: Saturday, August 24)

About 10.30 [at night] Robbie suggested to Edna [visiting] that they should go to Santon B. so Dave and I went too. Piled into the old, olde Bentley, Robbie driving most recklessly. … Coming back Dave and I sat in the back; Dave with his arm round me, singing. … As he remarked at the top of Irton fell, kissing in a Bentley is hugely invigorating. (Caldwell 1953: Friday, October 2)

All diaries must be interpreted with caution. We do not know what incidents and feelings a diarist chose not to record, and all life writing is to an extent a deliberate projection of a particular personality or image, even when the diary is ostensibly meant to be seen only by the diarist. However, what these nine accounts do demonstrate is that over a period of some eight decades all these young women were highly mobile; traveled by a variety of different means; used their mobility to progress their interests, love lives, and (in some cases) careers; and only rarely recorded inconveniences and constraints. All these young women inevitably operated within a particular societal framework that had established norms of behavior and activity for young women. But, within these structures, all the young women—whatever their social position or location—were able to some extent to exercise their own agency to negotiate quite high levels of mobility and individual freedom when they wished (Thomas Reference Thomas2016). In our readings of the diaries it is the similarity of experience and the extent of mobility for all nine young women that are most striking.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the staff at the Bishopsgate Institute Archive for access to diaries, and to Lynne Pearce and Siân Pooley for comments on the draft manuscript. An earlier version of the paper was presented at the European Social Science History conference in Belfast in April 2018. We are grateful for all the comments received during and after that session.