Introduction

Since the discovery of its psychedelic properties, d-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) has carried a paradoxical history. On one hand, LSD was applied as a psychosis model, owing to its similarity to the schizophrenic phenomenology (Geyer & Vollenweider, Reference Geyer and Vollenweider2008). On the other hand, it was applied as a therapeutic tool for conditions including alcoholism and mood disorders (Krebs & Johansen, Reference Krebs and Johansen2012; Reiff et al., Reference Reiff, Richman, Nemeroff, Carpenter, Widge, Rodriguez and McDonald2020). This study sought to bridge the gap between these parallel research lines by examining key parameters of both areas: aberrant salience reflecting psychosis model and suggestibility and mindfulness reflecting therapeutic models.

Regarding the psychosis model, there are remarkable similarities between psychedelic and psychotic experiences, namely altered perception of senses, self, body, time, altered emotions, impaired cognition, loss of intentionality, magical thinking, among other behavioral and neurophysiological phenomena (De Gregorio, Comai, Posa, & Gobbi, Reference De Gregorio, Comai, Posa and Gobbi2016; Geyer & Vollenweider, Reference Geyer and Vollenweider2008; Vollenweider & Geyer, Reference Vollenweider and Geyer2001). To explain the generation of psychotic experiences, schizophrenia research has emphasized salience processing. Salience is the quality of an element that makes it stand out from its environment and thereby catch attention, like a red dot on a wall (stimulus-driven) or a journal's impact factor for scientists (goal-directed) (Paulus, Rademacher, Schäfer, Müller-Pinzler, & Krach, Reference Paulus, Rademacher, Schäfer, Müller-Pinzler and Krach2015). Salience prioritizes relevant information and influences perception and behavior, including knowledge activation (Higgins, Reference Higgins1996), attribution of causality (Taylor & Fiske, Reference Taylor and Fiske1978), decision making (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974), and self- and other-perception (Callero, Reference Callero1985).

Aberrant salience is the ‘aberrant assignment of salience to external objects and internal representations’ (Kapur, Reference Kapur2003, p. 15) and possibly accounts for hallucinations and delusions in psychotic phenomena. It is related to delusions and negative symptoms in schizophrenia (Roiser et al., Reference Roiser, Stephan, Ouden, Barnes, Friston and Joyce2019) and psychotic experiences in first-episode psychosis and, to a lesser extent, healthy controls (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka and Morgan2016). Aberrant salience predicts anomalous experiences and paranormal attributions (Irwin, Schofield, & Baker, Reference Irwin, Schofield and Baker2014), increases with cannabis use (Bernardini et al., Reference Bernardini, Gobbicchi, Attademo, Puchalski, Trezzi, Moretti and Loas2018), and mediates the cannabis-induced development of schizotypal symptoms (O'Tuathaigh et al., Reference O'Tuathaigh, Dawes, Bickerdike, Duggan, O'Neill, Waddington and Moran2020). Altogether, these findings indicate a crucial role of aberrant salience in psychotic experiences. To evaluate the suitability of psychedelics as a psychosis model, an investigation of their effects on aberrant salience is therefore essential.

Regarding the therapeutic model, promising approaches to date seem to lie in psychedelic-induced suggestibility and mindfulness (Lemercier & Terhune, Reference Lemercier and Terhune2018; Walsh & Thiessen, Reference Walsh and Thiessen2018). Suggestibility is the tendency to react to suggestions. Suggestions influence cognition and behavior by guiding perception and assigning significance and support therapeutic processes (Gheorghiu, Reference Gheorghiu2000; Kirsch & Low, Reference Kirsch and Low2013; Michael, Garry, & Kirsch, Reference Michael, Garry and Kirsch2012). In hypnotherapy, suggestions induce cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physiological changes (Peter, Reference Peter, Kröner-Herwig, Freelöh, Klinger and Nigels2011) and suggestibility predicts treatment outcome in cases of pain, anxiety, somatization, asthma, and nicotine addiction (Lynn, Shindler, & Meyer, Reference Lynn, Shindler and Meyer2003; Montgomery, Duhamel, & Redd, Reference Montgomery, Duhamel and Redd2000). Suggestibility can be increased by hypnosis (Kirsch et al., Reference Kirsch, Etzel, Derbyshire, Dienes, Heap, Kallio and Whalley2011), training (Gorassini & Spanos, Reference Gorassini and Spanos1986), and psychedelics, including LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin (Carhart-Harris et al., Reference Carhart-Harris, Kaelen, Whalley, Bolstridge, Feilding and Nutt2015; Middlefell, Reference Middlefell1967; Sjoberg & Hollister, Reference Sjoberg and Hollister1965). Considering that psychedelics and hypnosis enhance suggestibility and share other similarities, a combination of both tools might potentially boost treatment efficiency (Lemercier & Terhune, Reference Lemercier and Terhune2018).

Mindfulness is the ‘intentional self-regulation of attention from moment to moment [and] detached observation’ (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn1982, p. 34). Mindfulness techniques are associated with improvements in mental health, depression, anxiety, stress, and pain management (Marchand, Reference Marchand2012). Mindfulness-related capacities can be increased by psychedelics, including psilocybin (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Fisher, Stenbæk, Kristiansen, Burmester, Lehel and Knudsen2020), ayahuasca (Murphy-Beiner & Soar, Reference Murphy-Beiner and Soar2020; Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Revenga, Valle, Roberto, Domínguez-Clavé, Elices and Riba2017), and 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) (Uthaug et al., Reference Uthaug, Lancelotta, van Oorsouw, Kuypers, Mason, Rak and Ramaekers2019). Remarkably, mindfulness increases seem to facilitate the therapeutic action of psychedelics in mood and substance use disorders (Mian, Altman, & Earleywine, Reference Mian, Altman and Earleywine2020; Walsh & Thiessen, Reference Walsh and Thiessen2018; Watts, Day, Krzanowski, Nutt, & Carhart-Harris, Reference Watts, Day, Krzanowski, Nutt and Carhart-Harris2017). However, to the best of our knowledge, the effects of LSD on mindfulness have not yet been investigated.

This study aimed at exploring the suitability of LSD as a psychosis model, as measured by aberrant salience, and as a therapy model, as measured by suggestibility and mindfulness, as well as the relationship between both models and the psychedelic experience. Our hypotheses were (1) LSD increases aberrant salience; (2) LSD increases suggestibility and mindfulness; and (3) there are positive correlations between LSD-induced aberrant salience, suggestibility, mindfulness, and psychedelic experience.

Methods

Study design

The study used a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design with two treatments (LSD; placebo) and a washout period of 14 days between treatments. Participants were randomly assigned to treatment order. This study was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee and the National Health Surveillance Agency and conducted according to safety guidelines for psychedelic research in humans (Johnson, Richards, & Griffiths, Reference Johnson, Richards and Griffiths2008).

Participants

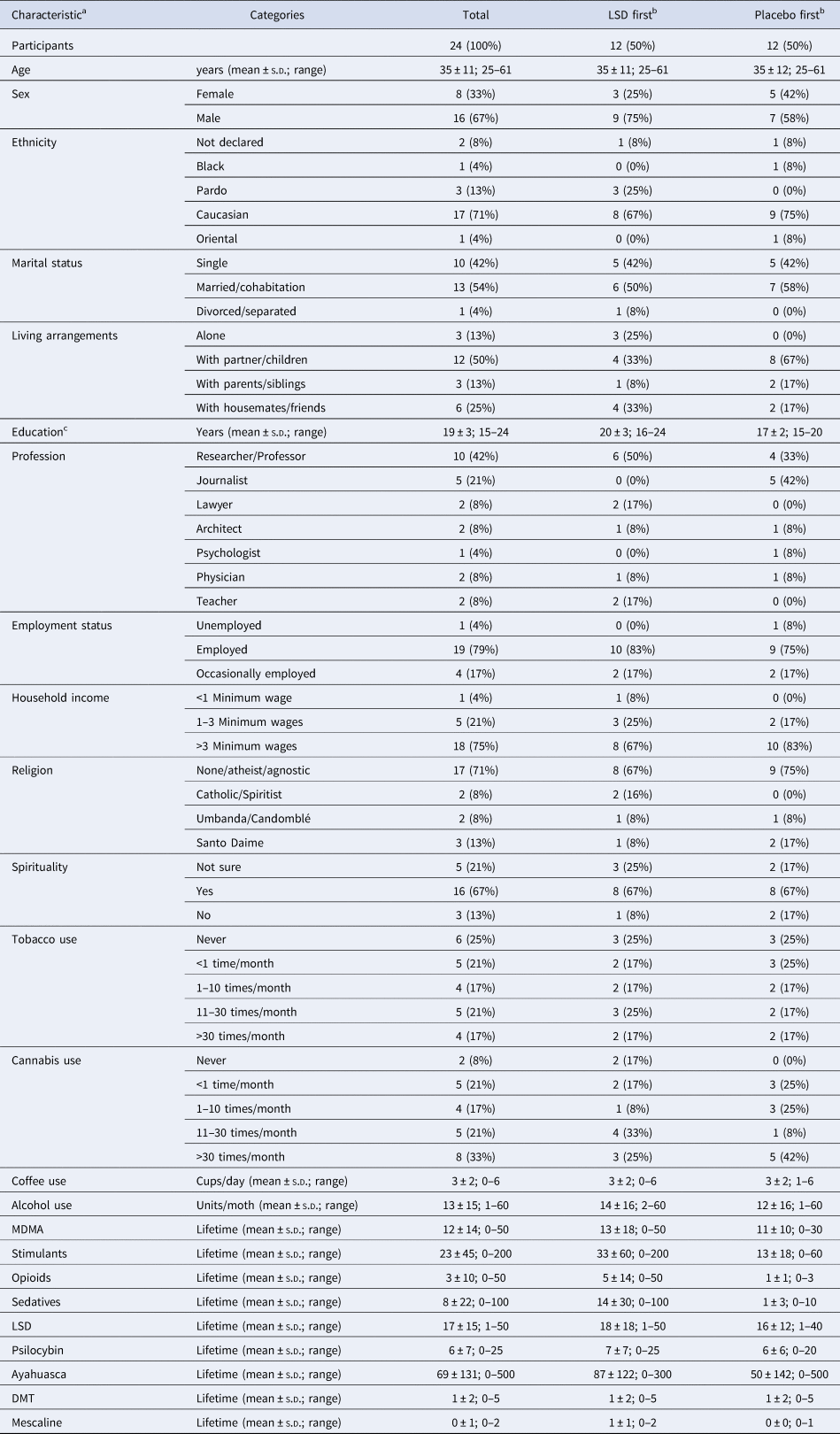

Twenty-five healthy participants were recruited in a convenience sample. Inclusion criteria were: age above 21 years, at least one experience with LSD, abstinence of at least 2 weeks from psychedelics and 3 days from alcohol and other drugs before each session and from tobacco and caffeine during the study days. Previous drug use was assessed by self-report questionnaires. Exclusion criteria were: presence of psychiatric symptoms, personal or first-degree family member history of psychotic disorder, use of psychiatric medication, history of severe complications after psychedelic use, alcohol or substance use disorder (according to DSM-5), heart disease or other relevant medical conditions, pregnancy, and non-native speaking of Brazilian Portuguese. Participants provided written informed consent before participation. One participant ceased participation after the first session for personal reasons, resulting in a final sample of 24 subjects. For demographic characteristics of the participants, see Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the study participants

a Data are based on self-reported information, including drug use experience and frequency.

b The two treatment order groups did not significantly differ on demographic characteristics, unless stated otherwise.

c Higher means in the group ‘LSD first’, as indicated by an independent samples t test.

Drug

Participants received 50 μg LSD (>99% purity on high-performance liquid chromatography; dissolved in alcohol solution) or inactive placebo (alcohol solution). Either substance was administered orally diluted in 30 ml water. The dose of 50 μg LSD is regarded as low and was chosen to minimize the risk of adverse reactions and exert noticeable effects without impairing the subjects' ability to complete the measurements (Holze et al., Reference Holze, Vizeli, Ley, Müller, Dolder, Stocker and Liechti2021; Majić, Schmidt, & Gallinat, Reference Majić, Schmidt and Gallinat2015; Passie, Halpern, Stichtenoth, Emrich, & Hintzen, Reference Passie, Halpern, Stichtenoth, Emrich and Hintzen2008). The absolute dose corresponded to a relative dose of (mean ± s.d.) 0.69 ± 0.18 μg/kg body weight (range = 0.45–1.11).

Measurements

Psychedelic experience

Subjective intensity and valence of drug effects were assessed by visual analog scales from 0 (no effect) to 100 (extremely intense effect) for intensity and from −50 (extremely unpleasant effect) to 50 (extremely pleasant effect) for valence. Both scales were applied as paper-and-pencil versions in 15 min intervals for 2 h, followed by 30 min intervals for 6 h. Maximum intensity (Intmax), maximum and minimum valence (Valmax, Valmin), area under the curve for intensity (IntAUC), and positive and negative valence (ValAUCpos, ValAUCneg) were calculated.

The LSD-induced experience was self-rated using Brazilian Portuguese versions of the Altered State of Consciousness Questionnaire (ASC) (Dittrich, Reference Dittrich1998; Studerus, Gamma, & Vollenweider, Reference Studerus, Gamma and Vollenweider2010), Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (MEQ) (MacLean, Leoutsakos, Johnson, & Griffiths, Reference MacLean, Leoutsakos, Johnson and Griffiths2012; Schenberg, Tófoli, Rezinovsky, & Da Silveira, Reference Schenberg, Tófoli, Rezinovsky and Da Silveira2017), Challenging Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ) (Barrett, Bradstreet, Leoutsakos, Johnson, & Griffiths, Reference Barrett, Bradstreet, Leoutsakos, Johnson and Griffiths2016; Schenberg, Reference Schenbergn.d.), and Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI) (Bienemann et al., Reference Bienemann, Longo, Multedo, Ruschel, Negreiros, Tófoli and Mograbi2020; Nour, Evans, Nutt, & Carhart-Harris, Reference Nour, Evans, Nutt and Carhart-Harris2016). The ASC contains 11 factors (Experience of Unity; Spiritual Experience; Blissful State; Insightfulness; Disembodiment; Impaired Control and Cognition; Anxiety; Complex Imagery; Elementary Imagery; Audio-Visual Synesthesia; Changed Meaning of Percepts), the MEQ four factors (Mystical; Positive Mood; Transcendence of Time and Space; Ineffability), and the CEQ seven factors (Fear; Grief; Physical Distress; Insanity; Isolation; Death; Paranoia; compare online Supplemental methods).

Aberrant salience

The Aberrant Salience Inventory (ASI) measures the trait aberrant salience using 29 items in yes–no format (Cicero, Kerns, & McCarthy, Reference Cicero, Kerns and McCarthy2010). The items form five factors (Increased Significance; Senses Sharpening; Impending Understanding; Heightened Emotionality; Heightened Cognition) and a total score of all yes-responses (Total). For this study, the trait scale was adapted to a state scale by converting items from present tense (‘do you ever feel’) into past tense (‘did you feel’) referring to the last 24 h. The English scale was translated into Brazilian Portuguese by our team; validation is currently in progress.

Suggestibility

The Creative Imagination Scale (CIS) measures suggestibility (Wilson & Barber, Reference Wilson and Barber1978). Participants are instructed to sit comfortably, close their eyes, and imagine as vividly as possible the suggestions read by the investigator. The protocol contains 10 items of different modalities (e.g. auditory, tactile, olfactory). Afterward, participants rate their imagined experience compared to a real experience on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all the same) to 4 (almost exactly the same). The material was translated by our team and split into two parallel versions (see online Supplemental methods). Version order was balanced across participants and counterbalanced across treatments, i.e. half of the participants completed version A under LSD.

All items are summed to a total score (Total). Additionally, the different modalities were explored by grouping similar items to the modality areas Weight (arm heaviness; hand levitation), Sensation (finger anesthesia; hot hand), Taste (water; orange), Extern Ambience (music; age regression), Intern Ambience (time distortion; relaxation). Notably, this analysis was exploratory because the scale is not intended to and might not adequately distinguish between modalities, especially within our split version.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was measured by Brazilian Portuguese versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, Reference Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer and Toney2006; De Barros, Kozasa, De Souza, & Ronzani, Reference De Barros, Kozasa, De Souza and Ronzani2014), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Brown & Ryan, Reference Brown and Ryan2003; De Barros, Kozasa, De Souza, & Ronzani, Reference De Barros, Kozasa, De Souza and Ronzani2015), and Experiences Questionnaire (EQ) (Fresco et al., Reference Fresco, Moore, van Dulmen, Segal, Ma, Teasdale and Williams2007). The Brazilian FFMQ contains seven factors (Observe; Describe‒Positive; Describe‒Negative; Act with Awareness‒Autopilot; Act with Awareness‒Distraction; Nonjudge; Nonreact). MAAS and EQ are unifactorial measuring Awareness and Decentering, respectively (see online Supplemental methods). All scales were rated referring to the last 24 h (Soler et al., Reference Soler, Elices, Franquesa, Barker, Friedlander, Feilding and Riba2016) and applied before drug administration (T0), 24 h afterward (T1), and 2 weeks afterward (T2).

Study procedures

Candidates for participation underwent a clinical and psychiatric interview including screening of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, medical anamnesis, physical examination, and check of a recent electrocardiogram. If indicated, complementary exams were consulted.

Each session consisted of 2 study days. On the day of drug administration, two investigators were present, a psychologist and a psychiatrist. At least one of them was continuously in the same room as the subject, who was only allowed to leave for visiting the bathroom. For each participant, the same investigators were present in both sessions and continuously available for questions and doubts via e-mail and phone.

At 7:30 a.m., the session started. The researcher explained the study aims and procedures, addressed questions, asked the subject to switch off the cell phone, and initiated the baseline measurements including mindfulness scales (FFMQ, MAAS, EQ at T0). LSD or placebo was administered at 9:30 a.m., followed by diverse tests and questionnaires throughout the day. Results of these additional measurements will be reported elsewhere. During task-free intervals, participants were allowed to draw, write or spend time with provided photobooks and metallic and wooden puzzle games but not to listen to music, read, work or access the internet or computer. A standardized snack was served at 11:00 a.m. and lunch at 1:40 p.m. Suggestibility (CIS) was tested at 2:15 p.m. lasting around 18 min. At 4:30 p.m., 7 h after drug administration, participants completed questionnaires on the psychedelic experience (ASC, MEQ, CEQ, EDI). At 5:30 p.m., 8 h after drug administration, the researcher ensured that the subject was feeling emotionally and physically well, answered possible questions and released the subject into the custody of a family member or friend. Next morning, the subject returned at 8:00 a.m., completed measurements of mindfulness (FFMQ, MAAS, EQ at T1) and aberrant salience (ASI), among others, and was released around 10:00 a.m.

All questionnaires were presented on a monitor via online survey tool LimeSurvey (Schmitz, Reference Schmitz2012). Two weeks after the second session, participants completed online follow-up measurements including mindfulness scales (T2). Four months after the second session, the last follow-up e-mail contact was made including qualitative questions on study participation and possible long-term effects. No persisting side effects were reported.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22). A repeated measure General Linear Model (GLMrep) with ‘treatment’ (LSD, placebo) as within-subjects factor and ‘treatment order’ as between-subjects factor was performed for each scale. For scales with several factors or time points, GLMreps were complemented by respective within-subject factors. Main effects of treatment, period, and carryover were examined, followed by pairwise comparisons for each factor and time point. Effect sizes were estimated using partial eta squared (η p2).

Spearman's rank correlation coefficients (r s) were calculated between LSD-induced changes (Δ = LSD − placebo) on psychedelic experience (ΔInt, ΔVal, ΔASC, ΔMEQ, ΔCEQ, ΔEDI), aberrant salience (ΔASI), suggestibility (ΔCIS), and mindfulness (ΔFFMQ, ΔMAAS, ΔEQ).

Significance level was set to α = 0.05, two-tailed. Results were Bonferroni-corrected post hoc for multiple comparisons unless stated otherwise. Therefore, p values were corrected by the number of factors or time points for pairwise comparisons and the number of scales (n = 11) for correlations, as follows: pcorrected = puncorrected × n.

Results

Psychedelic experience

Intensity and positive valence were increased under LSD compared to placebo, as measured by Intmax [F (1,22) = 195.42, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.90], IntAUC [F (1,22) = 203.16, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.90], Valmax [F (1,22) = 42.96, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.66], and ValAUCpos [F (1,22) = 20.80, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.49]. There was a significant, although weaker, period effect for IntAUC [F (1,22) = 7.02, p = 0.015, η p2 = 0.24; meansession1 ± s.d. = 209.4 ± 203.2, meansession2 ± s.d. = 153.3 ± 167.3; online Supplementary Fig. S1], which might be explained by higher expectations and insecurity regarding study procedures and drug effects in the first session. There were no other effects of period and carryover.

ASC ratings of one subject were lost due to a storage error, so n = 23 ratings were analyzed. There was a significant ASC main effect [F (1,21) = 99.01, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.83], with higher scores for LSD than placebo in Total and all factors (all p ⩽ 0.001) except for Anxiety (p = n.s.). Similarly, there was a main effect in MEQ [F (1,22) = 137.61, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.86], with higher scores for LSD than placebo in Total and all factors (all p < 0.001). There was a significant, although weaker, main effect for CEQ [F (1,22) = 32.63, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.60]. Pairwise comparisons revealed increases in Total, Grief, Physical Distress (all p < 0.001), Insanity (p = 0.040), and Isolation (p = 0.048). Moreover, EDI was significantly increased under LSD compared to placebo [F (1,22) = 32.21, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.59]. No effects of period or carryover were observed. Means (±s.e.m.) are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. LSD, compared to placebo, induced psychedelic experiences as measured by (A) Altered State of Consciousness Questionnaire (ASC) for all factors except for Anxiety, (B) Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI), (C) Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (MEQ) for all factors, and (D) Challenging Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ) for the factors Grief, Physical Distress, Insanity, and Isolation but not in Fear, Death, or Paranoia. Scores are displayed as mean (±s.e.m.) percentage of scale maximum in (A) 23 and (B-D) 24 subjects. * p ⩽ 0.05, *** p ⩽ 0.001 (Bonferroni-corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons). ASC: Unit, Experience of Unity; Spirit, Spiritual Experience; Bliss, Blissful State; Insig, Insightfulness; Disem, Disembodiment; Impair, Impaired Control and Cognition; Anxie, Anxiety; CImag, Complex Imagery; EImag, Elementary Imagery; Synae, Audio-Visual Synesthesia; Mean, Changed Meaning of Percepts. MEQ: Mood, Positive Mood; Transcend, Transcendence of Time and Space; Ineffab, Ineffability. CEQ: Distress, Physical Distress.

Aberrant salience

ASI scores were significantly increased under LSD compared to placebo [F (1,22) = 55.00, p < 0.001, η p2 = 0.71], with no effects of period or carryover. Pairwise comparisons revealed higher ratings for Total, Increased Significance, Senses Sharpening, Impending Understanding, Heightened Emotionality (all p < 0.001), and Heightened Cognition (p = 0.002; Figure 2A).

Fig. 2. LSD, compared to placebo, induced psychotic- and therapeutic-like experiences, respectively, as measured by increased (A) aberrant salience (Aberrant Salience Inventory, ASI) for all factors, with strongest effect in Senses Sharpening, and (B) suggestibility (Creative Imagination Scale, CIS) for different modalities, with strongest effects in Extern Ambience, followed by Weight, Sensation, and, marginally, Taste, but not Intern Ambience. Scores are displayed as (A) mean (±s.e.m.) percentage of maximum and (B) mean (±s.e.m.) in 24 subjects. # p ⩽ 0.06, * p ⩽ 0.05, ** p ⩽ 0.01, *** p ⩽ 0.001 ((A) Bonferroni-corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons, (B) uncorrected). ASI: Incr Signif, Increased Significance; Sens Sharp, Senses Sharpening; Imp Under, Impending Understanding; Heigh Emo, Heightened Emotionality; Heigh Cog, Heightened Cognition.

Suggestibility

CIS ratings were significantly increased under LSD compared to placebo [F (1,22) = 12.03, p = 0.002, η p2 = 0.35]. Pairwise comparisons revealed increases in the modalities Extern Ambience (p = 0.004), Weight (p = 0.024), Sensation (p = 0.047), and, marginally, Taste (p = 0.053), but not Intern Ambience (p = n.s.; due to the exploratory nature of the modality analysis, p values were not corrected for multiple comparisons; (Fig. 2B). No effects of period or carryover were observed.

Mindfulness

For FFMQ, MAAS and EQ, no main effect or pairwise comparison reached significance (online Supplementary Table S1, figure S2).

Correlations

Regarding aberrant salience, ΔASI Total was highly correlated with ΔASC Total (rs = 0.71, p = 0.002), ΔMEQ Total (rs = 0.72, p = 0.001), and ΔEDI (rs = 0.82, p < 0.001; Figure 3). Furthermore, there were several moderate to high factor correlations of ΔASI with ΔInt, ΔASC, ΔMEQ, and ΔEDI (Table 2). Regarding suggestibility, ΔCIS was not correlated with other LSD-induced effects (Table 2). Despite the lack of main effects in mindfulness, correlations of LSD-induced individual changes (ΔFFMQ, ΔMAAS, ΔEQ) were examined to gain insights into complementary phenomena. Interestingly, psychedelic experiences correlated positively with mindfulness at T1 (ΔASC and ΔMEQ with ΔEQ), but negatively with mindfulness at T2 (ΔASC, ΔMEQ, ΔEDI, and ΔASI with ΔEQ and ΔFFMQ Nonreact; Table 2, online Supplementary Fig. S3). Regarding psychedelic experience, there were several moderate to high correlations for ΔASC, ΔMEQ, and ΔEDI, few correlations for ΔVal, ΔCEQ, and none for ΔInt (online Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 3. Scatterplots depicting relationships between aberrant salience and psychedelic experience. LSD-induced aberrant salience (ΔASI Total, x-axis) correlated highly with (A) altered state of consciousness (ΔASC Total, y-axis; rs = 0.71, p = 0.002, n = 23), (B) mystical experiences (ΔMEQ Total, y-axis; rs = 0.72, p = 0.001, n = 24), and (C) ego-dissolution (ΔEDI, y-axis; rs = 0.82, p < 0.001, n = 24). All p values were Bonferroni-corrected post hoc for multiple comparisons. ASI, Aberrant Salience Inventory. ASC, Altered State of Consciousness Questionnaire. MEQ, Mystical Experiences Questionnaire. EDI, Ego-Dissolution Inventory. Total, total score.

Table 2. Relationships between LSD-induced changes in aberrant salience (ΔASI), suggestibility (ΔCIS), mindfulness (ΔFFMQ, ΔMAAS, ΔEQ), and psychedelic experience (ΔInt, ΔVal, ΔASC, ΔMEQ, ΔCEQ, ΔEDI)

Values depict Spearman's rank correlation coefficients for total and factor scores in n = 23 subjects (ΔASC) and n = 24 (all others), with significant correlations in bold. *p ⩽ 0.05, ** p ⩽ 0.01, *** p ⩽ 0.001, Bonferroni-corrected.

Sug, suggestibility; any, any scale factor; n.s., not significant; T1, 24 h after drug administration; T2, 2 weeks after drug administration; ASI, Aberrant Salience Inventory: Sign, Increased Significance; Shar, Senses Sharpening; Unde, Impending Understanding; Emo, Heightened Emotionality; Cog, Heightened Cognition; CIS, Creative Imagination Scale; FFMQ, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire: NReact, Nonreact; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; EQ, Experiences Questionnaire; Int, intensity; Val, valence; ASC, Altered State of Consciousness Questionnaire: Unit, Experience of Unity; Spirit, Spiritual Experience; Bliss, Blissful State; Insig, Insightfulness; Disem, Disembodiment; Impair, Impaired Control and Cognition; Anxi, Anxiety; CImag, Complex Imagery; EImag, Elementary Imagery; Synae, Audio-Visual Synesthesia; Mean, Changed Meaning of Percepts; MEQ, Mystical Experiences Questionnaire: Mystic, Mystical; Mood, Positive Mood; Transc, Transcendence of Time and Space; Ineffa, Ineffability; CEQ, Challenging Experiences Questionnaire; EDI, Ego-Dissolution Inventory.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study attempting to bridge the gap between psychedelics as a psychosis model and as a therapeutic model. We explored aberrant salience, as measure of the psychosis model, and suggestibility and mindfulness, as measures of the therapy model, as well as diverse facets of the psychedelic experience. Our hypotheses were (1) LSD increases aberrant salience; (2) LSD increases suggestibility and mindfulness; (3) there are positive correlations between LSD-induced aberrant salience, suggestibility, mindfulness, and psychedelic experience. LSD induced a psychedelic experience including alterations of consciousness, mystical experiences, ego-dissolution and mildly challenging experiences. Regarding the psychosis model, as hypothesized, LSD significantly increased aberrant salience. Regarding the therapeutic model, our hypothesis was partially supported, with LSD significantly increasing suggestibility but not mindfulness. Regarding the relationship between both models, as expected, psychedelic experiences were correlated moderately to highly positively with aberrant salience and moderately positively with mindfulness at T1 but, contrary to our expectations, there were moderate negative correlations of psychedelic experiences with mindfulness at T2 and no correlations for suggestibility.

Psychedelic experience

The low dose of LSD (50 μg) was utilized in psycholytic therapy in the past (Majić et al., Reference Majić, Schmidt and Gallinat2015) and is poorly investigated in modern studies. This dose exerted principally positive effects, as indicated by increased positive valence, Positive Mood (MEQ), only slightly increased Grief, Physical Distress, Insanity, and Isolation (CEQ), and unaltered negative valence, Anxiety (ASC), Fear, Death, and Paranoia (CEQ), supporting the notion that lower doses of LSD induce predominantly positive emotions (Carhart-Harris et al., Reference Carhart-Harris, Kaelen, Bolstridge, Williams, Williams, Underwood and Nutt2016; Dolder, Schmid, Müller, Borgwardt, & Liechti, Reference Dolder, Schmid, Müller, Borgwardt and Liechti2016; Holze et al., Reference Holze, Vizeli, Ley, Müller, Dolder, Stocker and Liechti2021; Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Enzler, Gasser, Grouzmann, Preller, Vollenweider and Liechti2015). This dose also induced mystical experiences and ego-dissolution, which seem to play a critical role in therapeutic processes. Psilocybin-induced mystical experiences induce personal and spiritual significance which account for long-term enhancements in openness, positive attitudes, and prosocial behaviors (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Johnson, Richards, Richards, Jesse, MacLean and Klinedinst2018; Griffiths, Richards, McCann, & Jesse, Reference Griffiths, Richards, McCann and Jesse2006; MacLean, Johnson, & Griffiths, Reference MacLean, Johnson and Griffiths2011), are related to increased alcohol and smoking abstinence (Bogenschutz et al., Reference Bogenschutz, Forcehimes, Pommy, Wilcox, Barbosa and Strassman2015; Johnson, Garcia-Romeu, & Griffiths, Reference Johnson, Garcia-Romeu and Griffiths2017) and reduced anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Johnson, Carducci, Umbricht, Richards, Richards and Klinedinst2016; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Bossis, Guss, Agin-Liebes, Malone, Cohen and Schmidt2016). Ego-dissolution might support an altered perspective on the self and increased self-acceptance (Fischman, Reference Fischman2019). A ‘psychedelic peak experience’, including ego-dissolution, transcendence of time and space, and meaningful insights, was suggested as an important mechanism in LSD-assisted psychotherapy (Gasser, Kirchner, & Passie, Reference Gasser, Kirchner and Passie2015). Our results indicate that even a low dose of LSD evokes this peak experience and, therefore, is of potential therapeutic value.

Psychosis model

LSD increased all aberrant salience factors, namely Senses Sharpening (reflecting thalamic sensory gating), Impending Understanding (feeling of the importance of one's own reasoning), Increased Significance (salience attribution to external or internal stimuli), Heightened Emotionality (the urge to make sense of this significance), and Heightened Cognition (the feeling of being part of something mystically or intellectually important) (Cicero et al., Reference Cicero, Kerns and McCarthy2010). The results support the suitability of the psychosis model especially regarding meaning attribution. This is consistent with previously reported subjective, behavioral, and neurophysiological similarities between psychedelic experiences and acute, early phases of psychosis (Geyer & Vollenweider, Reference Geyer and Vollenweider2008; Hermle & Kraehenmann, Reference Hermle, Kraehenmann, Halberstadt, Vollenweider and Nichols2016; Pienkos et al., Reference Pienkos, Giersch, Hansen, Humpston, McCarthy-Jones, Mishara and Rosen2019; Vollenweider & Geyer, Reference Vollenweider and Geyer2001), especially regarding meaning attribution: ‘There is a charismatic aspect to the experience of the LSD-intoxicated and schizophrenic patients, giving rise to the feeling that they are approaching the truth or gaining a true awareness of the world’ (Savage & Cholden, Reference Savage and Cholden1956, p. 409f) (Bowers & Freedman, Reference Bowers and Freedman1966; Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al., Reference Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, Habermeyer, Hermle, Steinmeyer, Kunert and Sass1998; Leptourgos et al., Reference Leptourgos, Fortier-Davy, Carhart-Harris, Corlett, Dupuis, Halberstadt and Jardri2020).Footnote †Footnote 1 Conversely, emotional aspects of aberrant salience and psychedelic experience showed few correlations, pointing to the limits of the psychosis model, since psychotic experiences exhibit strong, principally negative emotionality (Geyer & Vollenweider, Reference Geyer and Vollenweider2008; Hermle & Kraehenmann, Reference Hermle, Kraehenmann, Halberstadt, Vollenweider and Nichols2016; Young, Reference Young1974). Moreover, aberrant salience correlated highly with Complex Imagery, emphasizing the importance of psychedelic-induced visions for meaning attribution, while psychotic experiences are characterized by more auditory hallucinations (Hermle & Kraehenmann, Reference Hermle, Kraehenmann, Halberstadt, Vollenweider and Nichols2016).

Altogether, our findings highlight the potential of low psychedelic doses to induce psychotic-like, meaning-laden experiences, including hallucinations (Senses Sharpening) and delusions (Impending Understanding, Increased Significance, Heightened Cognition).

Beyond that, the correlations of aberrant salience with mystical experiences and ego-dissolution might point to common mechanisms for psychotic, therapeutic and psychedelic experiences. Specifically, LSD-induced aberrant salience might increase significance attribution and reduce ego boundaries and defense mechanisms, allowing for therapeutic changes in perspectives and attitudes (Fischman, Reference Fischman2019). Similarly, aberrant salience exerts a modulatory role within psychotic experiences related to cannabis use and self-concept clarity (Cicero, Docherty, Becker, Martin, & Kerns, Reference Cicero, Docherty, Becker, Martin and Kerns2015; O'Tuathaigh et al., Reference O'Tuathaigh, Dawes, Bickerdike, Duggan, O'Neill, Waddington and Moran2020). Moreover, considering that salience impacts attention, causality attribution, decision making, self-concept, role-identity, and moral reasoning (Bordalo, Gennaioli, & Shleifer, Reference Bordalo, Gennaioli and Shleifer2012; Callero, Reference Callero1985; Taylor & Fiske, Reference Taylor and Fiske1978; Trémolière, Neys, & Bonnefon, Reference Trémolière, Neys and Bonnefon2012), aberrant salience might provide an intriguing perspective to explain psychedelic phenomena including altered cognition, logical thinking, self- and other-perception, empathy, and prosocial attitudes.

Therapy model

LSD increased suggestibility in a manner similar to previous results (Carhart-Harris et al., Reference Carhart-Harris, Kaelen, Whalley, Bolstridge, Feilding and Nutt2015) despite the lower dose and later time point, when intensity had almost halved (means ± s.d.: ΔIntmax = 72 ± 27; ΔInt+5h = 39 ± 22). This might point to a ‘late therapeutic window’ in psycholytic therapy, with reduced intensity, cognitive impairment, emotional instability, and increased disposition to engage in therapeutic dialogue, similar to findings of a second LSD-induced peak in trust, happiness, openness, and wanting ‘to be with other people’ (Dolder et al., Reference Dolder, Schmid, Müller, Borgwardt and Liechti2016). LSD increased the modalities Extern Ambience, Weight, Sensation, and, marginally, Taste. The modulated Extern Ambience indicates application potential for mood disorders, where positive memories and imagery exert therapeutic benefits (Holmes, Lang, & Shah, Reference Holmes, Lang and Shah2009; Serrano, Latorre, Gatz, & Montanes, Reference Serrano, Latorre, Gatz and Montanes2004). Moreover, the results indicate application possibilities in hypnotherapeutic areas concerning memory integration (e.g. post-traumatic stress disorder), somatization, pain, and eating disorders (Godoy, Reference Godoy1999; Lynn et al., Reference Lynn, Shindler and Meyer2003; Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Duhamel and Redd2000). Notably, psychedelic-induced suggestibility needs to be prudently applied, since suggestions can engender potentially harmful results, including false memories (Michael et al., Reference Michael, Garry and Kirsch2012; Paddock & Terranova, Reference Paddock and Terranova2001). Future studies should confirm our exploratory results by focusing on psychedelic-induced mystical experiences, which act therapeutically in similar areas and might boost treatment efficacy if guided and potentiated by suggestions.

In contrast to previous findings, LSD did not increase mindfulness. This might be explained by previous studies assessing mindfulness in naturalistic settings (Murphy-Beiner & Soar, Reference Murphy-Beiner and Soar2020; Smigielski et al., Reference Smigielski, Kometer, Scheidegger, Krähenmann, Huber and Vollenweider2019; Soler et al., Reference Soler, Elices, Dominguez-Clavé, Pascual, Feilding, Navarro-Gil and Riba2018, Reference Soler, Elices, Franquesa, Barker, Friedlander, Feilding and Riba2016; Uthaug et al., Reference Uthaug, Lancelotta, van Oorsouw, Kuypers, Mason, Rak and Ramaekers2019) or with baseline comparisons (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Fisher, Stenbæk, Kristiansen, Burmester, Lehel and Knudsen2020; Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Revenga, Valle, Roberto, Domínguez-Clavé, Elices and Riba2017), allowing for setting or placebo effects which fundamentally influence psychedelic experiences (Olson, Suissa-Rocheleau, Lifshitz, Raz, & Veissière, Reference Olson, Suissa-Rocheleau, Lifshitz, Raz and Veissière2020). Moreover, our study applied no mindfulness-enhancing procedures, but assessed spontaneous changes. Alternatively, our low dose might not have exerted effects, while ritual doses are generally higher. Finally, substance differences might account for the discrepancy, since the naturally-derived ayahuasca (DMT), toad secretion (5-MeO-DMT), and mushrooms (psilocybin) contain diverse psychoactive components (Chen & Kovariková, Reference Chen and Kovariková1967; Domínguez-Clavé et al., Reference Domínguez-Clavé, Soler, Elices, Pascual, Álvarez, de la Fuente Revenga and Riba2016; Tylš, Páleníček, & Horáček, Reference Tylš, Páleníček and Horáček2014). Future studies should carefully disentangle influences of substance, dose, setting, and placebo effect.

Connecting psychedelic experience, psychosis model, and therapy model

Suggestibility was not correlated with other effects, contradicting the concern that psychedelic-induced suggestibility biases the psychedelic experience per se (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Richards and Griffiths2008) and indicating that therapeutic suggestions act independently of the psychedelic experience. Contrastingly, mindfulness changes were correlated with mystical experiences and ego-dissolution, positively in the short term and negatively in the mid-term. Similarly, previous findings reported positive relationships between ayahuasca-induced ego-dissolution and sub-acute mindfulness (Uthaug et al., Reference Uthaug, van Oorsouw, Kuypers, van Boxtel, Broers, Mason and Ramaekers2018) and negative relationships between psilocybin-related effects and long-term mindfulness (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Fisher, Stenbæk, Kristiansen, Burmester, Lehel and Knudsen2020). Overall, these results might indicate that psychedelic experiences facilitate spontaneous mindfulness in the short term but hinder it in the long term. However, due to the lack of main effects, conclusions must be drawn with caution.

Aberrant salience showed no correlations with suggestibility and few with mindfulness, indicating no close connection between the psychosis model and these specific therapeutic models. However, aberrant salience robustly correlated with mystical and ego-dissolution experiences, which are fundamental within psychedelic-assisted treatments (compare section ‘Psychedelic Experience’) and psychotic experiences. Psychotic experiences are associated with self-distortions (Cicero et al., Reference Cicero, Docherty, Becker, Martin and Kerns2015; Nordgaard & Parnas, Reference Nordgaard and Parnas2014), although these seem to differ quantitatively and qualitatively from psychedelic-induced self-distortions (Vollenweider & Geyer, Reference Vollenweider and Geyer2001). Mystical experiences are common in the psychotic phenomenology, comprise religious and mystical hallucinations and delusions, including a sense of noesis, heightened perception, and communion with the ‘divine’, and are phenomenologically similar to non-psychotic and psychedelic-induced mystical experiences (Buckley, Reference Buckley1981; Clarke, Reference Clarke2010; Hermle & Kraehenmann, Reference Hermle, Kraehenmann, Halberstadt, Vollenweider and Nichols2016; Leptourgos et al., Reference Leptourgos, Fortier-Davy, Carhart-Harris, Corlett, Dupuis, Halberstadt and Jardri2020; Lukoff, Reference Lukoff1985; Parnas & Henriksen, Reference Parnas and Henriksen2016; Stifler, Greer, Sneck, & Dovenmuehle, Reference Stifler, Greer, Sneck and Dovenmuehle1993).Footnote 2

The concurrency of mystical and psychotic experiences is reframed in some non-Western cultures as spiritual trance and shamanism (Castillo, Reference Castillo2003; McClenon, Reference McClenon2012). Similarly, the psychedelic use in shamanic rituals and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy underlies different conceptions of illness and healing (Metzner, Reference Metzner1998). With this in mind and considering the capacity of humans to experience mystical states (Buckley, Reference Buckley1981) and the importance of mystical experiences for therapeutic processes, our results suggest that mystical experiences might constitute the link between the psychosis model and therapy model. Consequently, a stronger cultural integration of mystical experiences might promote the understanding and improvement of mental health, in line with the call of a consciousness culture (Bewusstseinskultur) for a social dialogue on consciousness and promotion of self-awareness, from education in school (meditation, lucid dreaming, guided imagery) to the public stance toward psychiatric disorders, euthanasia, and the human striving for altered states of consciousness (Fink, Reference Fink2018; Metzinger, Reference Metzinger2006).

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. (1) Design: blinding was difficult to realize, although the low dose permitted a certain degree of blinding especially in less experienced subjects. The randomization method led to imbalanced education levels across groups (Table 1). The crossover design, chosen to reduce the sample size, carries risks of potentially undetected carryover effects, emphasizing the need for larger sample sizes. (2) Sample: the convenience sampling method led to underrepresented women, non-Caucasian ethnicities and low-educated people, reducing the generalizability to the wider Brazilian population. Results within our healthy participants need to be replicated in clinical populations. The lack of drug screening potentially led to disrespected abstinence periods. (3) Measurements: aberrant salience does not directly measure psychotic symptoms and should be complemented by additional measurements in future studies (e.g. Psychotomimetic States Inventory). These should also include pharmacological and neurophysiological assessments, since the brain mechanisms underlying our effects remain unclear. Moreover, future research should specify how mystical experiences are comparable in quality and quantity within the psychosis model and therapy model.

Conclusions

This study aimed at bridging the gap between psychedelics as a psychosis model and therapeutic model. The low dose of LSD is poorly explored in modern studies and provides insights for psychosis research and psycholytic therapy. LSD increased suggestibility but not mindfulness, suggesting that psychedelics act therapeutically if applied as a tool but are not necessarily therapeutic per se. Contrastingly, LSD spontaneously increased aberrant salience, indicating a greater weight of psychosis- than therapy-related aspects in the psychedelic phenomenology. In other words, the LSD state resembles a psychotic experience and offers a tool for healing. The results suggest that psychedelic and psychotic experiences share a mystical and ego-dissolution phenomenology which, as previously shown, is also important in therapeutic processes, pointing to mystical experiences as possible links between the psychosis model and therapy model. Future studies should explore suggestions guiding and promoting mystical experiences to boost efficiency of psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002531.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all our participants for their study participation and Dr Martin Wießner for his support in the area under the curve analysis.

Author contributions

IW designed and coordinated the study, acted as psychological cover of the study, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. MF conducted clinical interviews, selected participants, collected data, and served as psychiatric cover of the study. FPF contributed to data analysis. LFT designed the study, recruited and selected participants, and served as psychiatric cover of the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Financial support

This study received financial support from the Beckley Foundation and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.