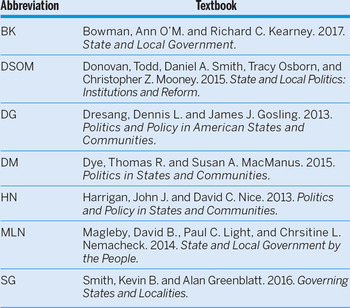

We review several textbooks, with the goal of providing a brief overview of the options available to scholars teaching undergraduate state and local government courses. This review provides a rudimentary comparison of these texts for both those looking for new texts and those who just want to explore potential options. Our examination is limited to general introductory, state and local texts, and omits texts that focus on a single state, as well as edited volumes like Politics in the American States (Gray, Hanson, and Kousser Reference Gray, Hanson and Kousser2013). We note texts that have brief editions, though we do not evaluate these versions the way we do for the full versions. We do not rank the best and worst texts, but provide several criteria by which prospective adopters might base their decision. We leave subjective assessments to readers. This review includes the following texts, and they are referenced by author initials (see table 1).

Table 1 Books Reviewed in this Article

We compare texts across several dimensions. First, we examine objectives, themes, and pedagogy of the texts. Some texts are designed to be more research focused, while others are designed to be more “accessible” for undergraduates. Some focus on concepts like reform, and others tend to emphasize public policies across their chapters. Second, we examine the specific chapter content in these texts. While all texts in our sample include chapters on federalism and state legislatures, there is variation in chapter topics. Most texts, for example, include a separate chapter on state constitutions, while others integrate this topic into one or more chapters. Third, we examine the scholarly nature of the texts. Fourth, we examine whether data and citations are current or dated. Fifth, we address the visuals offered in the texts, which include figures, maps, and tables. Finally, we mention other considerations that may be of interest to those selecting a state politics text.

OBJECTIVES, THEMES, AND PEDAGOGY

We first examine the objectives, themes, and pedagogy of each of the texts. We use these terms somewhat interchangeably because we found them interrelated in the vast majority of texts. Additionally, because texts have common features like introductions, key terms, glossaries, and references, we do not report them in table 2. We also emphasize that the number of examples in table 2 is not an indication of how extensive the authors are when it comes to objectives, themes, pedagogies, and features. Instead we present the key themes and important features that reflect the dominant pedagogies. We base our examination on information provided in the introductory pages of the texts, information that is provided by the authors, and information that is provided by the publishers. The advantage is that we are relying on those who know these texts best, as well as our own brief inspection of the opening discussions and relevant chapters of the texts. What we do not do is assess how well the texts incorporate these themes. So, while thematically, the DSOM text revolves around the importance of institutions and reforms, we leave interpretation of whether the authors do a satisfactory job of integrating these themes throughout the text to readers.

Table 2 Comparisons of Stated Objectives, Themes, and Pedagogies

It is clear from table 2 that there are significant commonalities in the objectives and themes. To be fair, all the texts address the role of institutions, and it is absurd to even contemplate that any of these authors would suggest that institutions do not matter. BK, MLN, and DSOM make specific reference to the role of institutions in their respective prefaces. DSOM, SG, and DM all emphasize comparisons and the comparative method in their prefaces. However, all the texts do compare states in a host of different ways in each chapter. Some texts appear to focus more heavily on research than others. DSOM, SG, and DG reference their focus on research and scholarship, however, mentioning scholarship in the preface does not mean that the text is comparatively strong in this area, and failing to mention it does not mean that it is weak. DSOM, DM, and HN indeed emphasize research in their respective texts. MLN and DG indicate accessibility as a theme in their text, something we similarly observe in our reading of the SG text. To be fair, all of the texts are accessible, though these three appear to make it an important focus.

There are also some themes that are more unique. The DSOM and HN texts focus on reform, while DM incorporate the theme of conflict management. Again, conflict and controversies are also addressed in all the texts, but particularly BK, HN, and DG. SG’s “States Under Stress” section addresses controversies and conflicts as they apply to budgetary constraints. This text is distinctive in its combination of academic and journalistic approaches to state and local politics. BK are unique in their stated focus on government capacity—the ability of government to adapt, manage conflict, and handle matters efficiently.

All of the texts have features designed to present various controversies, show how state and local politics affect citizens, lay out learning objectives, and provide additional resources. MLN, DSOM, and HN all have “You [Will] Decide” features, while the others have similar features to promote student interest. BK have a feature entitled “It’s Your Turn,” and DM include a “Did You Know?” feature. For instructors looking for a text that does not devote substantial attention to a multitude of features, and prefer texts that emphasize content, HN and DG may be good choices. The HN text, in particular, lacks many of the “bells and whistles” that have become standard in many texts. The text is grayscale only, and there are no photos, making the focus on the written content of the chapters, rather than a multitude of charts, graphs, tables, and other features. Some instructors may appreciate texts with fewer features, while those who prefer more visual learning may favor some of the other texts.

CONTENTS

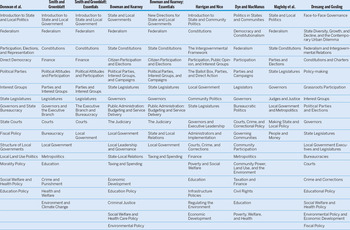

Perhaps a better way to assess what is between the covers of these texts is to examine the tables of contents, which we do in table 3. Chapters give us an indication of what the authors think is important, rather than some of the perhaps inflated language found in the prefaces. Additionally, the order of the chapters may be important to some instructors. All of the texts contain an introductory chapter, as well as chapters on state legislatures, governors/executive branch, the judiciary/courts, and local governments. Not surprisingly, all texts include topics such as participation and elections, political parties, and interest groups, though there is variation in how these topics are addressed. All texts have a chapter on federalism, though the HN text’s chapter is on intergovernmental relations, which includes federalism. DG’s chapter focuses on both topics. The DSOM text is the only one that lacks a dedicated constitutions chapter, though state constitutions are addressed in the introductory chapter. This text is also the only one to have a separate chapter on direct democracy, something that is not surprising given these authors’ expertise. The other texts incorporate direct democracy in other chapters. We also note unique chapters such as HN’s chapter on infrastructure policy and DM’s chapter on civil rights.

Table 3 Comparison of Tables of Contents

Some of the texts appear to make public administration an important component, likely as a result of research expertise of the authors. The BK, HN, and DM texts all devote substantial space to public administration, as well as political science. We already noted the intergovernmental and infrastructure chapters in the HN text, but these authors also include chapters dealing with community politics, administrators and implementation, economic development, and regulation. The BK text has a specific chapter devoted to public administration and budgeting, as well as two chapters on local governments, chapters on economic development, and various policy areas. The DM text includes a chapter on bureaucratic politics, as well as chapters on governing communities, metropolitics (dealing with mostly urban areas), and community power, land use, and the environment. SG can be paired with Governing magazine, which is a publication dealing with policy, politics, and state and local management.

All full versions of the texts include policy chapters. Despite some small differences, most of the texts cover social welfare and health policy, education policy, criminal justice policy, and the environment in some way or another. MLN include a single policy making chapter, and do not include separate chapters for different policy areas.

SCHOLARSHIP

Next, we evaluate how each text engages with the academic literature. We have amassed a dataset whose unit of analysis is each academic citation across two chapters: federalism and state legislatures. These chapters are common in all texts and are substantively critical topics to many state and local government scholars. We classify a citation as an “academic” if it represents an article in a peer-reviewed journal or monograph. Footnote 1 Although these data provide useful information about the extent to which these texts engage with academic research, we are unable to comment on the quality of each citation. Despite some differences, they tend to cite similar, peer-reviewed sources.

We evaluate three characteristics about these citations. First, what is the frequency of citations for each text? Do some of the texts engage more frequently with the academic literature than others? Second, what is the range of dates for these citations? Do these texts cite recent scholarship and make an attempt to update their chapters according to new research? Finally, how are these citations distributed across time, and from what years are the bulk of citations? We do not make normative judgements about the scholarship, and we recognize that classic scholarship, indeed, has an important place in any state and local texts.

We present our analysis in figure 1. It plots the density of each text’s citations by the year of each citation. We index the density to the raw frequency of citations for each text in order to simultaneously demonstrate the distribution and frequency citations. The similar skew for each distribution demonstrates that these authors favor more recent publications.

Figure 1 The Distribution of Academic Citations for Each Text

Still, there are some notable differences between these texts. First, DSOM stand apart, particularly in terms of their frequency of citations. Across our two chapters, we found that DSOM cite 191 academic publications. The runners-up for most citations are DM, with 110, and HN, with 109. We ordered the key of figure 1 in terms of the frequency of citations for each text. Additionally, the distribution for DSOM also has one of the strongest peaks, which features very recent publications. The median year for these citations is 2005, which is equal to or more recent than the other texts (BK are also 2005).

This is not to say that the other texts fail to engage academic scholarship. In fact, all the texts cite a good number of articles from very high quality outlets, such as the American Political Science Review, the Journal of Politics, the American Journal of Political Science, and State Politics and Policy Quarterly. Each text also includes a large mix of non-academic outlets like the Washington Post and the New York Times, which we do not include in our analysis.

For DG’s text, the peak of its distribution reveals the authors favor citing publications from the mid-1980s over more recent years. Indeed the median year of citation across the legislatures and federalism chapters in this text is 1984. Most other texts favor sources from 2000 and beyond. Footnote 2 Additionally, DG only include 30 citations according to our guidelines. The text still makes good use of non-academic publications like newspapers and annual additions of The Book of the States. The range of these data is very similar across these texts. With one exception, the most recent publication these texts cite is from 2012, 2013, or 2014. The exception is DG, whose most recent citation is from 2006.

Do any of these texts make an effort to update the data they use? Texts in political science have to cope with constantly shifting realities, particularly across editions. How well do these texts accomplish this task?

RECENCY AND ACCURACY OF DATA

Do any of these texts make an effort to update the data they use? Texts in political science have to cope with constantly shifting realities, particularly across editions. How well do these texts accomplish this task?

We looked for data that these texts each present in one of the common chapters (federalism and legislatures). We found that each text includes information on the partisan composition of state legislatures or state governments. These data are useful for a variety of reasons. For one, the partisan composition of state legislatures varies significantly in many states from election cycle to election cycle. During the 2014 elections, Republicans won a majority of seats in eleven chambers that previously had Democratic majorities. Additionally, these data are useful because they provide readers with very useful descriptive information about states’ current political climate.

Table 4 shows that none of these texts is more than two years (or one election cycle) out-of-date in its presentation of data on the partisan composition of state legislatures. For example, DG and HN use data from 2011, but both of these texts were published in 2013. We also compared each text’s data against information the National Conference of State Legislatures publicly provides on the historical partisan composition of each state legislature. On this issue, each text appears committed to keeping up-to-date and accurate data, and we expect the same on other issues. However, it is important to note that our analysis is limited to data commonly presented across texts.

Table 4 Presentation of State Legislative Partisan Data for each Textbook

PRESENTATION OF DATA

We also evaluate how these texts present data through visuals, particularly in tables, figures, and maps. We first discuss how each presents data on the partisan composition of state legislatures. However, we push further by also looking at how they present other data. How many graphs, tables, and maps do they present? What is the most common form of visual, and how much variation is there across texts? Do any or all of the texts present unique or otherwise notable data in these common chapters?

Table 4 provides information on how each text presents data on state legislatures’ partisan composition. DSOM present these data in their richest form, providing the partisan makeup of each legislature in numbers of Republicans, Democrats, and Independents by chamber in a table. This table provides more information than any of the other texts on state legislatures’ partisan composition, but in doing so it also sacrifices efficiency.

The most common method of presenting these data is in the form of 50-state maps. BK, MLN, DG, and SG present partisan data with such visuals. SG produce data aggregated to a higher unit by also including the partisanship of the governor. These maps classify states or legislatures as: Democratic, Republican, or Split/Divided. They are visually appealing, simple, and they efficiently present meaningful information about the states’ political climates. Even so, they also sacrifice richness in the information (e.g., majority party size).

Finally, DM and HN present this information temporally. These texts show the number of legislatures that are controlled by Democrats and Republicans, or are Split/Divided, by a selected set of years. Readers may more freely draw connections between state politics and national political events, like presidential elections. However, readers will not be able to draw any regional trends with these data.

We also surveyed all of the tables, maps, and figures across the two common chapters and found most texts use a good mixture of all three. BK include four tables, four figures, and three maps across their chapters on legislatures and federalism. DM use the most tables (5), figures (8), and maps (5) with a total of 18 in these chapters. DSOM have the second most tables (5), figures (4), and maps (7) with a total of 16. This text also uses the most maps. MLN and HN include the fewest visuals at nine each. HN also have the fewest maps, and, as a text is the least reliant on any form of visualization.

We also took note of any unique data these texts present. Constraining our sample to include each text’s chapter on legislatures alone, we classify information as unique if we were unable to get the same information from any of the other text’s visuals. We found no unique material presented in texts by DG, HN, or SG.

DSOM provide ideology scores for the party caucuses in each legislature. This text also provides an index score for each state in terms of the power of state house speakers. This unique information is consistent with DSOM’s commitment to the literature. BK present a scatterplot comparing legislative professionalism to public approval of state legislatures. MLN provide a table with the 10 most effective lawmakers in the NC senate and assembly for 2009 and 2011. This information helps engage students and other readers with real life examples. Finally, DM produce a table that lists all of the presidents who were also state legislators. This list demonstrates to readers the importance of legislatures in America’s political ladder.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Some instructors may prefer texts that have been staples of the state and local government text market for years. The MLN text is in its 16th edition, and the DM text is in its 15th edition. HN, BK, and DG have texts in their 11th, 10th, and 8th editions, respectively. For those preferring a fresh approach, Donovan et al. and SG have texts in their 3rd and 5th editions, respectively.

State and local text prices are substantial. Many of the texts and their publishers have several pricing options that include packaging with several supplements, hardcover versus softcover choices, full versus essential versions of the texts, and ebooks, so comparisons are difficult. Prices are also susceptible to fluctuations, availability of new and used copies, retail versus wholesale prices, and other considerations. Still, we did conduct a brief review of the publishers’ suggested retail prices for all of these texts, and a few things stand out. The most economical text is the SG text, which ranges from about $119 to $131, depending on how it is packaged. The midrange priced texts are by DM, HN, and MLN, which range from about $155 to $178. It appears that BK, DG, and DSOM all retail for $200 or more, with BK having a list price of about $235. Ebooks are available for each of the texts, and the price ranges from about $46 to $95; interestingly, the Cengage texts—BK and DSOM—appear to have the least expensive electronic options.

All of the texts have a range of features designed to encourage students, demonstrate how the state and local governments are relevant, and to improve student performance. The texts have a number of provisions for both students and instructors, including instructor’s editions, test banks, student quizzes, lecture slides, and learning management programs or the ability to integrate with existing ones. Many of the ancillary materials are as much a product of the publishers as the texts themselves. Given the consolidation of publishing companies, many of the texts have similar ancillary materials. Four of the texts—MLN, DG, DM, and HN—are published by Pearson, so they have similar resources, though there are some differences across texts even with the same publishers. Cengage publishes DSOM, as well as BK, which both have ample resources available to both students and instructors. The SG text is published by Sage/CQ Press, and it can be paired with access to substantial state data (State Stats); it also has additional materials for students and instructors.

FINAL THOUGHTS

In this review, we discuss the themes, topics, cost, visuals, and quantity and distribution of scholarship in the prominent state and local government texts. We found notable similarities and differences across texts in these categories. Ideally, we would evaluate every chapter for each of these texts, but topical and pedagogical differences make systematic comparisons problematic. Still, our analysis of two critically important chapters—federalism and state legislatures—should provide useful information to instructors. The discussion of themes, costs, and features should offer additional information that instructors might consider as a starting point in their adoption decisions. But this review is no substitution for examining these texts personally, as we all have different criteria for evaluating texts; the good news is there are many quality options.