Background

Improving sexual health outcomes for young people is a national priority for the UK government [Public Health England (PHE), 2015a]. This includes reducing the rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) which are currently on the rise, with around 440 000 new diagnoses made in England in 2014 (PHE, 2015b). STIs are a public health issue associated with infertility, cancer, and psychological and social difficulties [World Health Organisation (WHO), 2013]. The Government’s sexual health priorities also include tackling teenage pregnancy, which is linked with increased likelihood of infant mortality, childhood accidents and living in deprivation (Moffitt, Reference Moffitt2002) and is estimated to cost the NHS £63 million annually [Department of Health (DH), 2009]. School nurses (SNs) are specialist community public health nurses working with the school age population to promote their health and well-being (DH, 2014a). These specialists are qualified nurses with an additional specialist public health qualification. However, there is no requirement that their preparation programmes contain sexual health education, so the knowledge base of qualifying practitioners will vary. There are only just over 1000 SNs across the United Kingdom, supporting approximately nine and a half million children and young people [Royal College of Nursing (RCN), 2017]. To deliver a comprehensive service, SNs are supported by community staff nurses working across groups of schools rather than working in one school. In England since 2012, the service has been commissioned by Local Authorities, which has resulted in a variable level of service delivery (RCN, 2017). As public health nurses working with this population they are arguably in a prime position to promote the sexual health of children and young people. The DH (2014b) identifies that SNs have a role in sexual health including developing school-based health services, delivering sex and relationships education (SRE) and offering condom distribution schemes.

Sexual health has been a major feature in national public health policy since the release of the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (Social Exclusion Unit, 1999). Most recently the Local Government Association (2016) report ‘Good progress but more to do: teenage pregnancy and young parents’, highlights that although the under-18 conception rate has halved since 1998, it remains high compared with other countries in Western Europe and across United Kingdom boroughs there is a large variation in rates of teenage pregnancy which has contributed to health inequalities. In the London borough which formed the focus of this study the conception rates are 27.4, which is significantly higher than the London average of 21.5 for under-18 conceptions and the England average of 22.8 per 1000 for 15–17 year olds (Office for National Statistics, 2016). The borough also had a significantly higher rate of diagnosis of STIs including chlamydia in the 15–24 year age group in 2014 compared with the London average (PHE, 2016). With regard to STI’s (excluding chlamydia diagnoses in the 15–24 year age group), in 2014 2465/100 000 diagnoses were made in the Borough, compared with the London average of 1534/100 000 and the England average of 829/100 000 (PHE, 2016). Data from 2014 shows the Borough to have the 5th highest rates of chlamydia diagnosed in the population aged 15–24 in London, with chlamydia being detected in 3241 out of 100 000 15–24 year olds (PHE, 2016).

A scoping review of the literature was undertaken to identify the breadth of research available, this followed the approach and steps developed by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). The scoping review identified 18 papers published between 1999 and 2016, these were published in the United Kingdom, United States and South Africa and revealed that SNs are perceived to have a variety of roles within sexual health. These include delivering SRE (McFayden, Reference McFayden2004; Jones, Reference Jones2008; Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Koren, Morgan, Shipley and Hardy2014), leading drop-in clinics (Richardson-Todd, Reference Richardson-Todd2006; Ingram and Salmon, Reference Ingram and Salmon2010), supplying contraception (Richardson-Todd, Reference Richardson-Todd2006; Ingram and Salmon, Reference Ingram and Salmon2010), including emergency contraception (Richardson-Todd, Reference Richardson-Todd2006; RCN, 2012), and referring to other services (RCN, 2012; Dittus et al., Reference Dittus, De Rosa, Jeffries, Afifi, Cumberland, Chung, Martinez, Kerndt and Ethier2014). McFayden (Reference McFayden2004) identified that although the majority of SNs in their UK-based study viewed themselves as having a role in sex education, many lacked confidence in this area in contrast to a small American study by Brewin et al. (Reference Brewin, Koren, Morgan, Shipley and Hardy2014) which found that SNs felt comfortable in this role. McFayden’s findings may be reflected in those of Reid and Teijlingen’s (Reference Reid and Teijlingen2006) UK focus group study with young people, where SNs were generally viewed as poor sources of information. However, healthcare facilitators such as SNs were preferred over teachers to deliver SRE.

Although some young people view SNs as a poor source of sexual health information, a British Youth Council (BYC) (2011) online survey completed by a sample of 1599 young people aged 11–18 in England found that advice on contraception, STIs and referring to other services were listed in the top five services young people felt SNs should provide. The perception that SNs do have a role in sexual health has further been supported in a case study by France (Reference France2014), where a SN text messaging service was established in two UK secondary schools, with 56% of text messages received from students being related to sexual health.

The view of school staff regarding the sexual health role of SNs is under researched. However, in a questionnaire completed by 86 UK secondary school Personal, Social, Health Education (PSHE) coordinators and head teachers on emergency contraception, 55% reported that they would inform their SN if a 14-year old asked for emergency contraception, suggesting they perceive the SN to have a role in this area (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Dawson and Moore2000). Overall there seems a consensus in the published literature that young people, teachers and parents value the contribution of the SN with SRE (Jones, Reference Jones2008; BYC, 2011).

Collaboration was recognised as an important area to examine within the literature, to explore the importance of student and staff input in directing the planning and delivery of school health services. Working in collaboration with the school age population has been identified as important for sexual health service development. Reid and Teijlingen (Reference Reid and Teijlingen2006) in their Scottish study argue that the views of young people should be considered when planning and delivering SRE as generally their participants viewed SRE as outdated and ineffective. Hayter et al. (Reference Hayter, Owen and Cooke2012) further supported this by highlighting the importance of involving young people in service design and evaluation to promote attendance and a user-friendly service. Collaboration also needs to extend to school staff and parents, some of whom have expressed a fear that the service will lead to increased sexual activity amongst young people, which can act as a barrier to service delivery (Schmiedl, Reference Schmiedl2004). Hayter et al. (Reference Hayter, Owen and Cooke2012) found that such opposition can be tackled through consultation with parents, head teachers and governors.

Owen et al. (Reference Owen, Carroll, Cooke, Formby, Hayter, Hirst, Lloyd-Jones, Stapleton, Stevenson and Sutton2010) and Hayter et al. (Reference Hayter, Owen and Cooke2012) found that SNs delivering a holistic approach, incorporating sexual health, promoted access to sexual health services by minimising sexual health associated stigma. In a systematic review exploring young people’s views on school sexual health services, the offer of free condoms, increased opening hours, a convenient but private location and knowledge of a confidential service, were all found to improve access (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Lloyd-Jones, Cooke and Owen2011). Interestingly, the BYC Survey (2011) revealed 39% of young people felt unsure if their confidentiality would be maintained, potentially creating a barrier to access. A barrier which potentially could be overcome through a text messaging service as 76.2% of survey respondents in France’s (Reference France2014) study felt the texting service was a good way to seek health advice.

Methods

This study aimed to explore the role and activities of the school nursing service in sexual health within one London borough. Objectives:

(1) To establish the number and nature of referrals received by the school nursing service in relation to sexual health.

(2) To identify the views and experiences of SNs, using a questionnaire survey, on their role in sexual health, the service they currently deliver in this area and the factors that hinder service delivery.

(3) To identify the views and experiences of school staff, using a questionnaire survey, on the SNs’ role in sexual health, the service they currently receive and factors which stop them from using the service.

Ethical approval was gained from a London University and permission was granted from the NHS Trust providing school nursing services within the borough. As this study aimed to assess existing practice (Mateo and Foreman, Reference Mateo and Foreman2014) a mixed methods approach was taken gaining quantitative and qualitative data through an audit of documentary data and questionnaire surveys to explore existing school nursing practice in the borough, related to sexual health. Three teams of SNs across the borough were trained in the use of an audit tool which had been developed by the authors. The audit was then undertaken for a three-month period to identify the nature of the referrals related to sexual health. Although the audit tool had not been previously validated it was designed based on the scoping review of literature and the authors’ experience of school nursing practice. The inclusion criteria for the audit are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 Audit inclusion criteria

Following permission from the service manager for school nursing and head teachers within the borough’s 21 secondary schools, a SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc., 2017) web link was emailed to all SNs working in secondary schools in the borough (n=8) and a different web link was emailed to a member of staff in each secondary school, identified by the head teacher as the most appropriate person to complete the questionnaire (Appendices 1 and 2). The roles of these staff included deputy head teachers, inclusion managers, special educational needs coordinators and safeguarding officers. Although it could not be guaranteed who completed the survey by aiming for a staff member who was actively working with the school nursing service, it was hoped that a realistic picture would be gained. As such a purposive sample was sought to gain the most meaningful information (Holloway and Wheeler, Reference Holloway and Wheeler2010) and the use of the SurveyMonkey ensured anonymity which was important considering the small size of the samples. To ensure SNs did not feel coerced into participating, the SN service manager, acting as gatekeeper, rather than the researchers contacted staff members informing them about the study and provided an information sheet. The service manager asked that staff willing to participate contact one of the authors to gain the web link. All eight SNs participated giving a 100% response rate and nine teaching staff, giving a 42.8% response rate. Although the latter is low it is an acknowledged limitation of self-completion questionnaires (Parahoo, Reference Parahoo2014). The small population size prevented pre-testing of the surveys, however, these were scrutinised by the all members of the project team, the Trust’s research and development lead and the university’s ethics committee. The two questionnaires (Appendices 1 and 2) included nine questions. In the SN survey there were seven forced choice questions with some space for comments, plus two open-ended questions seeking SN participants’ perceptions of barriers and areas for development regarding their role in sexual health. The teaching staff survey included space for additional comments on the closed questions and one open-ended question asking what further support or input would be valued from the school health service related to sexual health.

Data were analysed using quantitative and qualitative methods. The audit data and the closed and multiple-choice questions on the surveys provided numerical data regarding the input provided from the school nursing service in relation to sexual health. The data produced from the closed questions was mostly nominal, with one question self-rating confidence for both school staff and SNs, which produced ordinal data. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data. The open-ended survey questions produced a limited amount of qualitative data, which both researchers analysed by reading several times to identify participants’ perceptions of barriers and developments regarding sexual health services. This data added depth to the quantitative data by the small sample of survey participants (Holloway and Wheeler, Reference Holloway and Wheeler2010).

Findings

Audit

The audit of documentary data took place over a three-month period and monitored referrals received by the school nursing service in relation to sexual health from accident and emergency departments, the safeguarding children’s team, schools and self-referrals via the SN drop-in. During this time, a total of 46 referrals were received by the school nursing service in relation to sexual health.

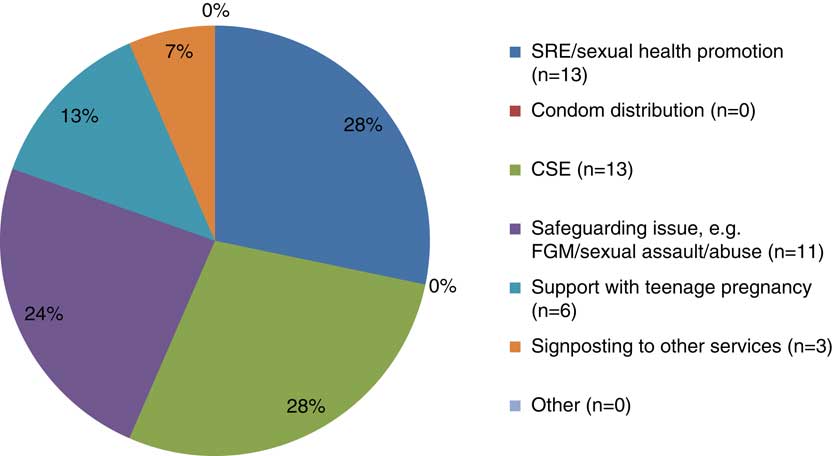

Over a third (37%, n=17) of the total referrals received by the school nursing service in relation to sexual health were from the safeguarding children’s team or children’s social care, including 10 (58.9%) related to child sexual exploitation (CSE). Accident and emergency departments were the least common referral source with just seven referrals (15%) received over the three-month period. These data are consistent with the information provided by both SNs and school staff that safeguarding children and young people was identified as a main role of SNs within the context of sexual health. The majority of drop-in attendances were for SRE/sexual health promotion (n=10, 70%), including advice on STIs and contraception, which is perhaps reflective of the self-referral nature of the drop-in service. The referral reasons from accident and emergency departments and schools were much more sporadic and included referrals requesting support with teenage pregnancy, referring to other services and safeguarding issues. The specific reasons for referrals are outline in Figure 1.

Figure 1 A pie chart to show the reasons for the referrals received by the school nursing team (NB. signposting in figure is a synonym for referring). SRE=sex and relationships education; CSE=child sexual exploitation; FGM = female genital mutilation

The teenage pregnancy referrals along with those for safeguarding are perhaps suggestive of a more reactive provision of sexual health support from the school nursing service. Only a quarter (28%, n=13) of referrals were related to sexual health promotion which may be considered a more proactive area of support; with an aim of preventing STIs, teenage pregnancy and promoting healthy relationships.

Regarding gender just 15% (n=7) of the referrals received by the school nursing service were regarding males. Considering that the borough’s school age population is close to 50% males this suggests that they are underrepresented with regard to the sexual health referrals received by the school nursing service. No males were recorded to have attended the SN drop-in for sexual health support during the audit period and no sexual health referrals were received from accident and emergency departments regarding males; suggesting that the young male population in the borough are not accessing sexual health support from the school nursing service. Eighty five per cent of referrals relating to males were regarding a safeguarding issue including five (71.4%) CSE referrals. This finding highlighted further that particularly for the male population the majority of referrals indicate a reactive sexual health provision.

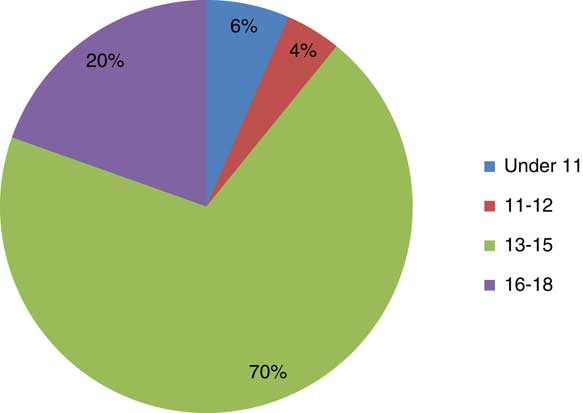

Regarding age, 70% of referrals received by the school nursing service were related to young people aged 13–15 (n=32), Figure 2.

Figure 2 Pie chart showing the percentage of referrals received by age

Children aged 12 and under comprised just 10% of the total referrals received (n=5); with all referrals for children within the under 11 and 11–12 age category related to CSE. This highlights the need for PSHE for primary school age children to incorporate age appropriate information on CSE and healthy relationships.

SN survey: responses to closed questions

From the SN survey responses to the closed questions, it was identified that all eight SNs recognised that they had an active role in sexual health, with all stating this role involved safeguarding and the HPV vaccination programme. Five of the SNs reported that they had supported between one and nine young people within the previous month where sexual health was the main focus of contact. In addition, one further SN reported that sexual health support was offered as part of a broader health assessment. Overall the SNs reported supporting a mean estimate of 2.68 students in the past month where sexual health was the main focus of the contact, compared to a mean estimate of 8.13 students who were reported to have received sexual health support as part of a broader health review with the SN. On the whole, the type of contact was reportedly one to one rather than group SRE sessions. Only four SNs had offered group sessions during the previous year with only one SN delivering more than four sessions. These data suggest inconsistencies in service delivery.

All the SNs reported that they had received training in the last five years to support children and young people with sexual health. However, when asked to rate their confidence in this area of practice only one SN rated themselves as being very confident on a scale of 1–5 (with one being not confident at all and five meaning very confident), the other seven SNs rated themselves between one and four. Unsurprisingly the SN who reported undertaking the most group sessions also reported having the highest confidence in this role.

School staff survey: responses to closed questions

Similarly, to the survey for SNs, all nine school staff respondents identified SNs as having a role in sexual health in response to the closed survey questions. They were also more likely to view SNs as having a role in delivering sex education to students on a 1:1 basis (100%, n=9) compared with group education (66.67%, n=6). This may be related to the frequency that support is observed based on the findings from the SN survey.

School staff were asked to identify the number of students they had been aware of in the last month who had required sexual health support, the number they had referred to the school nursing service and the number they had encouraged to attend the SN drop-in. The findings indicated that not all students requiring sexual health support are referred to the school nursing service or encouraged to attend the SN drop-in clinic (Table 2).

Table 2 Sexual health support requested by school staff

The survey responses suggested that school staff were aware of a mean estimate of 3.77 students who had required sexual health support in the last month, yet out of these students, 55.56% (n=5) of respondents had not referred any to the school nursing service. This suggests that although some students are referred to the school nursing service for sexual health support, it does not reflect the number that school staff know require support. A third of respondents identified that they had encouraged students to attend the SN drop-in. However, one respondent added a comment that they could not do this because the service was not available in their school.

The most common requests for support from school staff related to safeguarding and referring students to other services [62.5% (n=5) of respondents]. This correlates with the perception by school staff where 88.89% (n=8) identified that SNs have a role in safeguarding and referring students to other services. In this context, safeguarding is recognised to be a broader term than ‘child protection’, relating to the promotion of children’s welfare of children and their protection from harm (Department for Education, 2015). Interestingly, only 44.44% (n=4) of respondents reported that their school had received support with SRE from their school nursing service in the last year. Two respondents ticked that they received SRE from another agency which may help to explain this figure.

Closed question responses also indicated that the most common reason for school staff not involving the school nursing service, identified by three respondents, was that other services are available to support students with sexual health. These services include local sexual health clinics and clinics for the under 25s. One respondent ticked that the SN is not always available and another that the length of time taken for the SN to act upon the referral is too long. This links to the barrier of time identified by some of the SNs completing the questionnaire survey. Interestingly, one respondent ticked that they felt their school did not need support in the area of sexual health.

Qualitative survey data

A small number of open-ended questions were included in the survey, these explored the barriers to providing sexual health services and the developments SNs and teachers would like to see in this area of activity. Four barriers were identified, along with lack of confidence mentioned by one SN, which was also highlighted by the quantitative data. The other barriers were lack of resources (one respondent), difficulty getting school staff on board with services such as condom distribution and SRE delivery (two respondents). The main barrier raised was lack of time to deliver a sexual health service (three respondents), with one respondent whose view was reflective of the other two stating:

‘Supporting schools with the preparation and teaching around sexual health is very time consuming, [there is] not enough staff, time, etc.’.

Seven of the SNs reported that they would like to see their role in sexual health develop. Their suggestions, included expansion of the service to enable SNs to offer pregnancy testing, testing for STIs and condom distribution, are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3 School nurse suggestions for the development of the service in sexual health

SRE=sex and relationships education; STI=sexually transmitted infections.

When asked what could support these aspirations for a developed service further training was the main need reported (Table 4).

Table 4 School nurse suggestions as to what would support the development of the school nursing service in sexual health

STI = sexually transmitted infections; c-card = condom-card, condom distribution scheme.

Schools said they would like their school nursing service to provide more sex education sessions, small group work with young people identified to be at risk of STIs or pregnancy and a school health clinic to support more young people to self-refer for support, advice and help from the SN.

One respondent commented that a high staff turn-over prevented them from utilising the school nursing service, with another respondent stating:

‘I feel that we get a very good service from the school nurse team when the school nurse is available, but we do have trouble at times due to staff shortages’.

This highlights the issue of the importance of SNs having the time to build consistent relationships with their schools to enable service delivery, which was raised by one SN. SNs working collaboratively with education staff and parents underpinned many of the aspirations and wishes mentioned within the survey responses. This is reflected in the comment of one respondent:

‘School nurses building relationships in schools through consistency as this role requires the school to trust the school nurse and the young people to be familiar with them. It can only be achieved if the school nurse is seen regularly working with the school to create a positive non-judgmental ethos in addition to confidential private spaces where young people can discuss their sexual health’.

Discussion

It appears that there is a variance in the provision of sexual health services delivered by SNs across the world (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Koren, Morgan, Shipley and Hardy2014; Minguez et al., Reference Minguez, Santelli, Gibson, Orr and Samant2015) the UK (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Carroll, Cooke, Formby, Hayter, Hirst, Lloyd-Jones, Stapleton, Stevenson and Sutton2010; BYC, 2011) and within the borough from this study’s findings. This does not promote a vision of equality outlined by NHS England (2013) and may contribute to health inequalities. The differences in the borough’s sexual health service provision across the school nursing service may be explained by varying health needs across the community but could also be a reflection of the varying confidence and capacity of each staff member, or a lack of clear policy to set a standard for SNs to adhere to in the area.

Where sexual health support is being provided by SNs, findings suggest a more reactive service provision, with the majority of referrals received relating to safeguarding concerns or teenage pregnancy. The findings suggested that less time is spent delivering strategies such as sexual health promotion (accounting for 28% of referrals) and offering contraception (accounting for 0% of referrals). In line with the NHS five year forward view [National Health Service (NHS) England et al., 2014], which argues that preventative healthcare is more cost-effective and contributes to better health outcomes for the population, a more proactive approach to sexual health service delivery may be a way forward for SNs. This has been found to be beneficial in other areas, for example Ingram and Salmon (Reference Ingram and Salmon2010) evaluated a school-based drop-in service over a 15-month period where out of a total of 515 visits, 42% of young people attended for free condoms. Schmeidl (Reference Schmiedl2004) argues that the availability of condoms in schools can increase condom use for young people and subsequently help to prevent pregnancy and the spread of STIs. Furthermore, a US-based study by Dittus et al. (Reference Dittus, De Rosa, Jeffries, Afifi, Cumberland, Chung, Martinez, Kerndt and Ethier2014) identified that providing SNs with a referral guide to help direct young people to sexual health services, increased the uptake of contraception, STI testing and treatment for female students. Taking into account the views of young people, the BYC (2011) identified that young people age 11–18 want their SN to advise them on contraception, STIs and refer them to other sexual health services and Reid and Teijlingen (Reference Reid and Teijlingen2006) found that young people want a healthcare professional to deliver SRE. This provides evidence that from the perspective of young people, they too would value a service that has a preventative approach.

The importance of collaboration with education providers in enabling sexual health service delivery was highlighted in the questionnaires completed by SNs and school staff and appears particularly relevant to areas such as condom distribution, drop-in clinics and SRE, which are reliant on permission from school staff and parents to take place in school. Findings from the surveys and audit also suggest that although young people are able to self-refer through drop-in clinics, the school nursing service is mainly reliant on referrals to the service from other agencies, including school staff, to help them identify those in need of sexual health support. This reliance highlights the importance of raising the profile and role of school nursing with such services, to instigate referrals, as findings from the surveys suggested that the service was underused in comparison to the number of students that school staff were aware of who needed sexual health support.

Carroll et al. (Reference Carroll, Lloyd-Jones, Cooke and Owen2011) identified that young people were not always aware of SN led sexual health services. A SN respondent to the survey identified that support from school staff to promote the school nursing service with students may increase access to the service for young people. This provides another example of how collaborative work with school staff may help to promote the provision of sexual health support by increasing attendance at SN drop-in clinics. This appears particularly important as the audit of documentary data identified that over a three-month period there were only 10 attendances to the SN drop-in related to sexual health across the borough. This may also be related to other factors such as the timing of the drop-in and the suitability of the space in which the drop-in takes place, which have been identified as factors important to young people in promoting attendance (Hayter et al., Reference Hayter, Owen and Cooke2012).

Some young people within the borough are accessing the school nursing service for sexual health support, as evidenced in the audit of documentary data. However, in comparison to the estimated 50 900 young people aged 10–19 years living in the borough and the high rates of STIs and under-18 conceptions, it is considered that not enough people are accessing the service. Furthermore, a quarter of school staff survey respondents identified that they had not requested any sexual health support from their SN in the past year. The viewpoint of one teacher that sexual health support was not needed in their school is important to consider given the high rates of under-18 conceptions and STIs in the borough (PHE, 2016). Arguably if school staff do not perceive sexual health to be an area of need for their school they are unlikely to request or facilitate interventions such as SRE or condom distribution in school; thus, creating a barrier to service delivery.

Access was identified as being a particular issue for those aged under 12 and males, who were only referred for school nursing support following concerns of CSE. Interestingly, Dittus et al. (Reference Dittus, De Rosa, Jeffries, Afifi, Cumberland, Chung, Martinez, Kerndt and Ethier2014) found that referring males to sexual health support did not improve their uptake of STI testing or treatment; suggesting difficulty in supporting males to access sexual health services.

Mathews et al. (2015) found that attendance at a greater number of SRE sessions for young people was associated with an increased likelihood of visiting the SN for support. This highlighted a potential benefit of SNs delivering SRE in schools, unfortunately, less than 50% of schools completing the survey had received SRE support from their SN in the last year. For school staff who identified barriers to accessing sexual health support from the school nursing service, 37.5% were related to issues with time and the capacity of their SN. This was reiterated by the SNs, with 37.5% identifying that time created a barrier to service delivery. Arguably a lack of time may limit the capacity of SNs to offer sexual health support. This highlights the benefit of incorporating sexual health support into other aspects of existing school nursing practice; for example, through drop-in clinics and general health assessments, as this should not create any additional time costs for SNs and is in keeping with a holistic approach. This may also be beneficial for young people who were reported to prefer a holistic approach to sexual health services to help reduce the stigma associated with accessing sexual health support (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Carroll, Cooke, Formby, Hayter, Hirst, Lloyd-Jones, Stapleton, Stevenson and Sutton2010).

Limitations and recommendations

It is recognised that the small sample size drawn upon in this study results in weak findings, which do not enable the findings to be generalised to a wider population. However, such a sample size is not surprising when considering the number of SNs in practice and therefore it is positive that the survey completed by SNs achieved a 100% response rate, alleviating non-response bias and minimising the risk of sample bias (Parahoo, Reference Parahoo2014). A response rate of 42.8% for the survey completed by school staff is considered by Mateo and Foreman (Reference Mateo and Foreman2014) to be inadequate. It is therefore recommended that further research is undertaken involving larger numbers of SNs and school staff, along with parents and young people to ensure their views of the service are reflected.

The service recommendation from this study is for school nursing services to promote a preventative approach to sexual health service delivery, one way of achieving this would be to incorporate the administration of contraception, emergency contraception and STI self-testing kits into drop-in clinics, in line with national recommendations (RCN, 2012; DH, 2014a). This may promote access to the school nursing service by offering services that are wanted by young people (BYC, 2011). A local policy setting a standard for sexual health service delivery within school nursing would also be necessary to promote consistency across the service.

In conclusion, the role of the SN in sexual health includes delivering SRE, safeguarding children and young people who have experienced or are at risk of harm and leading school-based clinics offering sexual health promotion and contraception. For SNs in the area studied, the service provision appears to be predominantly reactive to safeguarding concerns and issues such as teenage pregnancy. However, there is scope for a more preventative approach with both SNs and school staff outlining a vision for future service development that includes greater SRE, condom distribution and targeted group work for those identified as being at risk of STIs or pregnancy. However, this is reliant on SNs having the time, training, confidence and resources to deliver such services. It is also reliant on them working collaboratively with school staff and parents who are ultimately the stakeholders determining if such interventions can take place in schools.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Appendix 1: Survey for school nurses

The role of the school nurse in sexual health-survey for school nurses

The World Health Organisation (2006) defines sexual health as ‘a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.’

(1) What is your current role in sexual health? (Please select all that apply.)

∙ Providing sex and relationships education to groups in schools.

∙ Providing sex and relationships education to students on a 1:1 basis.

∙ Condom distribution.

∙ Support with teenage pregnancy.

∙ Support with FGM.

∙ Support with Child Sexual Exploitation.

∙ Safeguarding Children and Young people.

∙ Referring/signposting children/young people to other services.

∙ HPV vaccination programme.

∙ No role.

∙ Other (please specify) ______________________

(2) In the last month, how many clients have you supported where sexual health was the main focus of the contact?

0 1–4 5–9 10–15 16–20 21+

(3) In the last month, how many clients have you provided with advice/support around sexual health as part of a broader health assessment/review?

0 1–4 5–9 10–15 16–20 21+

(4) In the last year, how many group health promotion sessions have you delivered in secondary schools around sex and relationships education?

0 1–4 5–9 10–15 16–20 21+

(5) Have you received training to support children and young people with sexual health?

Yes No

If yes, please explain _________________________

(6) How confident do you feel in promoting the sexual health of children and young people? (Please rate from 1–5, where 1 means not confident at all and 5 means very confident.)

1 2 3 4 5

(7) What are the barriers to you carrying out a role in sexual health?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

(8) Would you like to see the role of the School Nurse in sexual health develop and if so in what ways?

Yes No

If yes, please explain _________________________

(9) If you would like to see the role developed, what do you think would support this development?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix 2: Survey for school staff

The role of the school nurse in sexual health: survey for school staff

The World Health Organisation (2006) defines sexual health as ‘a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled’.

(1) What is your understanding of the role of the School Nurse in sexual health? (Please select all that apply.)

∙ No understanding.

∙ To provide sex and relationships education to groups in schools.

∙ To provide sex and relationships education to students on a 1:1 basis.

∙ Condom distribution.

∙ Support with FGM.

∙ Support with teenage pregnancy.

∙ Support with Child Sexual Exploitation.

∙ Safeguarding Children and Young people.

∙ Referring/signposting to other services.

∙ HPV vaccination programme.

∙ Other (please specify) ______________________

(2) In the last month, how many students are you aware of that have required support around sexual health?

0 1–4 5–9 10–15 16–20 21+

(3) In relation to the above students, how many did you refer to the School Nurse?

0 1–4 5–9 10–15 16–20 21+

(4) In relation to the above students, how many did you encourage to attend the School Nurse drop-in (as oppose to making a referral)?

0 1–4 5–9 10–15 16–20 21+

Please state why ____________________________

(5) In the last year, what support has the school requested from the School Nursing service in relation to sexual health? (Please select all that apply.)

∙ No support in relation to sexual health has been requested.

∙ Sex and relationships education to group/s in schools.

∙ Sex and relationships education to student/s on a 1:1 basis.

∙ Contraceptive advice.

∙ Advice around sexually transmitted infections.

∙ Condom distribution.

∙ Support with FGM.

∙ Support with teenage pregnancy.

∙ Support with Child Sexual Exploitation.

∙ Safeguarding children and young people.

∙ For student/s to be referred/signposted to other services.

∙ For information sharing.

∙ Other (please specify) ______________________

(6) In the last year, has your School Nurse delivered/supported the school to deliver sex and relationships education to students?

Yes No

Comments ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

(7) How confident do you feel in your School Nurse’s ability to support children and young people with their sexual health? (Please rate from 1–5, with 1 meaning not confident at all and 5 meaning very confident.)

1 2 3 4 5.

(8) What is preventing you from utilising the School Nursing service to support with sexual health? (Please select all that apply.)

Nothing, I am utilising the School Nursing service for support with sexual health.

I wasn’t aware that the School Nurse could support students around sexual health.

The school does not need support in this area.

Other services are available to support students around sexual health.

We prefer to utilise the School Nurse for other aspects of students’ health and well-being.

It is difficult for us to get parental consent (where applicable) to make a referral.

Our School Nurse is not always available.

The length of time taken for the School Nurse to act upon the referral is too long.

Our School Nurse does not have the appropriate resources to manage the issue.

Other (please specify) ______________________

(9) What further support/input would you like from your School Nurse in relation to sexual health?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________