Introduction

In light of climate change and increasing the severity and frequency of disasters, health care organizations should be able to improve their service delivery during disasters through studying and learning from past disasters that they have faced. Reference El Sayed, Chami and Hitti1–Reference Bikomeye, Rublee and Beyer5

The health system has a crucial role in upholding resilience and adaptive capacity as a part of climate change adaptation and disaster resilience. Reference Bikomeye, Rublee and Beyer5,Reference Bayntun, Rockenschaub and Murray6 Globally, there are several models for hospitals’ “learning from disasters.” Reference Aiello, Khayeri and Raja7–Reference Ybarra10 However, in practice, most hospitals still need to undertake such learning. For example, in a study conducted to investigate tertiary hospitals in Shandong Province (China), only one-half (49%) of the surveyed hospitals developed post-disaster evaluation reports about prior experience and evaluation gained from these disasters to improve their future performance. Reference Zhong, Hou and Clark11

In 2019, the world faced a disaster in the form of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Although novel in its typology, this pandemic was preceded by other global pandemic concerns in the preceding decade, including Zika, influenza, and Ebola virus infections in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Reference Hannan, Lundholm, Brierton and Chapman3,Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8 Despite these opportunities to practice various pandemic response measures, the impact of COVID-19 was still overwhelming for many hospitals around the world. Reference Hannan, Lundholm, Brierton and Chapman3

COVID-19 led to the evolution of senior hospital personnel appreciating the significance of effective organizational planning and communication to successfully respond to the pandemic. Reference Hannan, Lundholm, Brierton and Chapman3,Reference Costa Font, Levaggi and Turati12,Reference White, Barello and Cao di San Marco13 Moreover, it launched a telemedicine revolution. Reference Iyengar, Mabrouk, Jain, Venkatesan and Vaishya14 It was apparent that clinical staff can quickly learn from and embed successful reactions to the pandemic. Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8,Reference Iyengar, Mabrouk, Jain, Venkatesan and Vaishya14 However, the longevity of the organizational memory of the prior experience and evaluation was less well-understood. Reference Huang15 Disaster preparedness information can enable resilient health care organizations and policy development. Nevertheless, the lived experiences of hospitals appear ad hoc and championed based on the application of learnings to improve performance. Reference Drevin, Alvesson, van Duinen, Bolkan, Koroma and Von Schreeb16–Reference Scrymgeour, Smith and Paton19

As a part of continuous improvement, system performance evaluation includes the monitoring, measurement, exploration, and appraisal of the process. Reference Rodríguez-Rey, Palacios and Alonso-Tapia20 The Deming cycle (the Plan-Do-Study-Act [PDSA] cycle) is an essential component of quality improvement in complex systems with unpredictable processes. Previous efforts have been made within the health care sector to improve hospitals’ capabilities to identify obstacles challenging the post-incident organizational learning process. These efforts included integrating organizational learning theory with the Deming cycle. Reference Eboreime, Olawepo, Banke-Thomas and Ramaswamy21,Reference De Savigny and Adam22

Hospitals are considered disaster-resilient when they can endure the disaster’s effects, decrease death and morbidity, and provide their patients with services of the same quality and frequency as everyday services. Reference Zhong, Clark, Hou, Zang and FitzGerald23 Resilience engineering (RE) is considered a successful approach to organizational change management towards improved performance, providing continuity during uncertainty. Reference Bouloiz24 Four RE capabilities categories comprise the abilities to: (1) respond to events (Actual); (2) monitor on-going developments (Critical); (3) anticipate future threats and opportunities (Potential); and (4) learn from past failures and successes (Factual). Reference Pariès, Wreathall, Hollnagel, Wreathall and Hollnagel25 In a previous paper, the authors conceptualized a RE-based framework to improve hospitals’ disaster resilience. The reviewed literature was considered in the first three RE categories (ie, Actual, Potential, and Critical). Reference Ali, Desha, Ranse and Roiko26

The fourth RE capability, Factual, was addressed in the current integrative review through the research questions: “How are hospital decision makers learning by responding to disasters towards improved hospital resilience?” and “How are such insights translated into action?”

Methods

Design

This integrative literature review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff27 for data collection and the well-established five steps of Whittemore and Knafl Reference Whittemore and Knafl28 framework for data analysis.

Data Collection

Papers were collected from various databases and search engines as evidence artifacts to be included in this review. Peer-reviewed articles were searched for from the publication dates of January 1, 1990 through February 28, 2021. This included the following databases: Web of Knowledge/Web of Science Core Collection (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA); MEDLINE (US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA; Lloyd Wommack, personal communications); CINAHL (EBSCO Information Services; Ipswich, Massachusetts USA); and Scopus (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands). The search strategy included trying different combinations of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords relevant to “hospitals,” “learn,” “disaster response,” and “resilience.” The resultant search string used is as follows:

(Hospital* OR Health Care Facilities, Manpower, and Services OR Health Facilities OR Academic Medical Centers OR Ambulatory Care Facilities)

AND TOPIC: (Perceiv* OR Learn* OR Lesson OR Pivot OR Adapt OR Recall OR Recollect* OR Remember OR Reflect* OR Continuous Improve*OR Success*OR Total Quality Management)

AND TOPIC: (Disaster Response OR Disaster Planning OR Emergencies OR Emergency Shelter OR Mass Casualty Incidents OR Medical Countermeasures OR Natural Disasters OR Rescue Work OR Crisis) AND TOPIC: (Resili*).

Articles were restricted to the inclusion criteria (considering peer-reviewed journal research articles written in English) and besides application of exclusion criteria (psychiatric, community, and individual types of resilience without reference to hospitals).

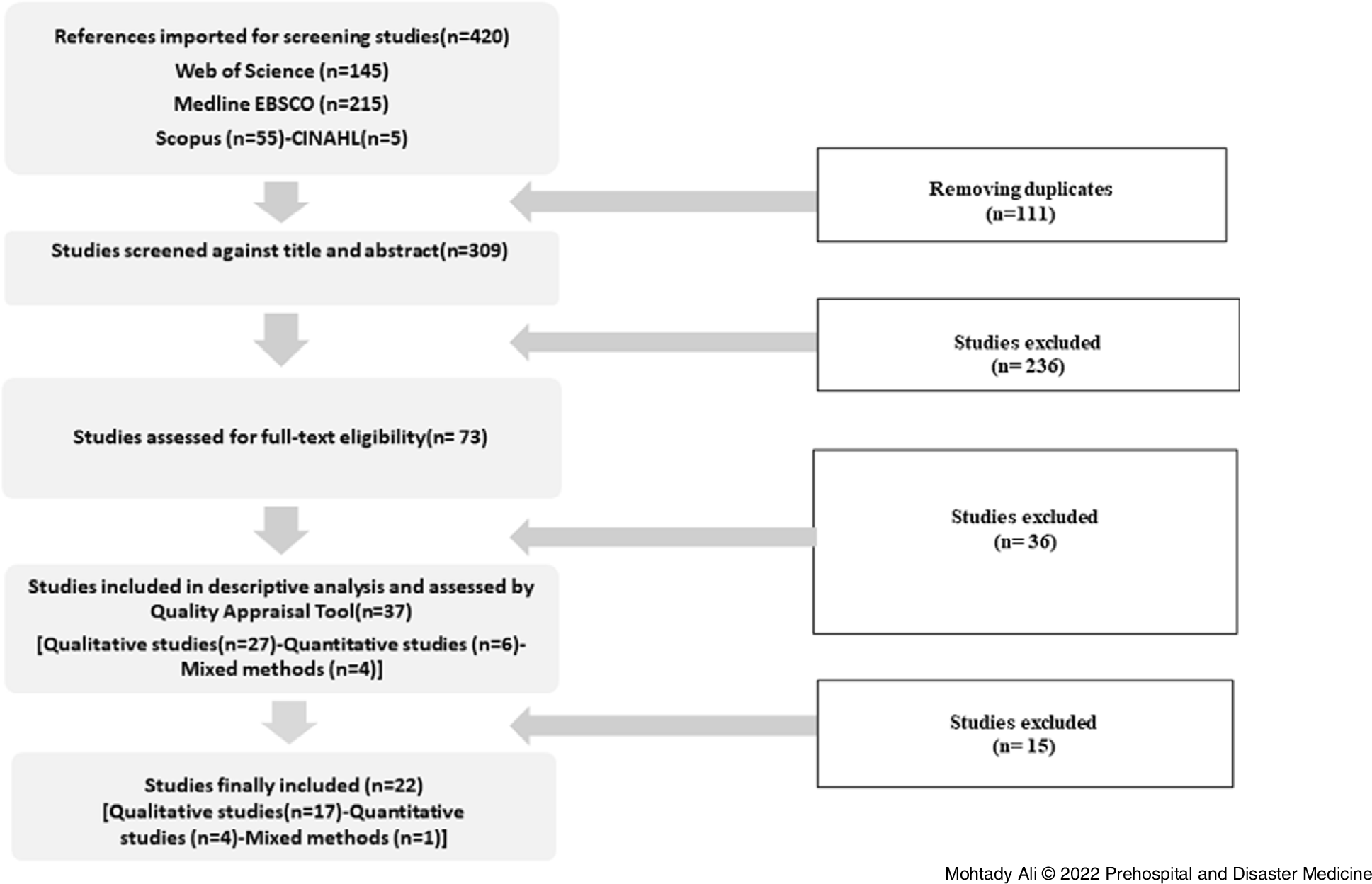

The search results (420 articles) were imported into Covidence (Covidence systematic review software; Veritas Health Innovation; Melbourne, Australia) and duplicate records (111) were removed. A minimum of two reviewers conducted the title and abstract screening, full-text screening, and final determination of eligibility and study inclusion. This process started by screening the abstract blindly via Covidence. A third reviewer resolved any conflicts.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was undertaken using the approach from the Whittemore and Knafl Reference Whittemore and Knafl28 framework. An assessment of the quality of the research methodology was undertaken using the revised Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT). Reference Hong, Fàbregues and Bartlett29 Each item of MMAT was given a specific value according to the availability of the criterion (Yes [2]; Somewhat/Partially [1]; and No/Cannot Tell/Not Addressed [0]). Articles should have been assessed as more than 70% to be included in the current study. Information extracted from each paper was entered into a Microsoft Word 2018 table (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA). This information included: author(s), journal, country, type of disaster, methods, and the key themes. The conclusion regarding the number of resources included was reached through rigorous application of the PRISMA method, consultation with expert librarian support, and using Covidence software in blind review to ensure that: (1) the search for papers was adequately scoped about the search strings and the chosen databases; and (2) the curation of papers used appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

Out of 73 full-text screened papers, 37 papers were identified as being relevant to this study. Figure 1 summarizes the screening process against the PRISMA diagram. The quality appraisal tools yielded 22 articles for thematic and content analysis following the descriptive analysis (Supplementary Tables 1-3; available online only).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Chart (Literature Review Selection Process).

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis.

Descriptive Analysis

There has been a gradual and significant increase in relevant publications since 2006, with a peak in 2019-2021 when 16 out of 37 (43.2%) of the articles were published.

Several types of disasters were investigated in these 37 papers, including 15 papers that addressed infectious disease-related disasters (COVID-19 [11]; Ebola [2]; and non-specific infections [2]), followed by nine papers addressing disasters caused by extreme weather events (EWEs) like hurricanes (3), non-specific EWE (3), flood (2), and typhoon (1). There were five papers regarding mass-casualty incident (MCI)/terroristic attack/bombing, two earthquakes, and one bushfire. Five studies addressed non-specific disasters.

Following the application of the quality appraisal tools, 22 articles were included. Out of these 22 articles, two addressed non-specific disasters and 20 investigated specific disaster types. These specific disasters included infectious diseases (10: COVID-19 [6], Ebola [2], and non-specific infections [2]); EWE (7), and MCI/terroristic attacks/bombing (3; Supplementary Table 4; available online only).

Thematic and Content Analysis

First, the various frameworks and theories addressed in the literature were summarized; second, the adopted thematic and content analysis approach was explained; and third, the learning opportunities were depicted.

Frameworks and Theories—The system standards, theories, and frameworks adopted or addressed in the included articles were recognized and summarized (Supplementary Table 5; available online only). In addition, those relevant to resilience, disaster management, public health, quality and accreditation, or organizational management were depicted as follows.

Four studies adopted the PDSA quality cycle. Reference El Sayed, Chami and Hitti1,Reference Brandrud, Bretthauer and Brattebø30–Reference McDaniels, Chang, Cole, Mikawoz and Longstaff32 Ten thematic categories described by Meyer, Bishai Reference Meyer, Bishai and Ravi33 as the resilient health systems components and included “core health system capabilities/capacities, infrastructure/transportation, financing, barriers to care, communication/collaboration/partnerships, leadership/command, surge capacity, risk communication, workforce, and workforce infection control.” Reference Meyer, Bishai and Ravi33 Five categories were identified by Walton, Navaratnam Reference Walton, Navaratnam, Ormond, Gandhi and Mann34 as themes for the UK’s emergency departments during COVID-19. These themes were departmental reconfiguration, clinical pathways, governance and communication, and workforce personal protective equipment (PPE). Eleven essential elements of public health emergency preparedness in the Resilience Framework for Public Health Emergency Preparedness (RFPHEP) Reference Khan, O’Sullivan and Brown35 were adopted by Aliyu, Norful Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8 to explore clinical staff’s preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic. The RFPHEP included governance and leadership, planning process, collaborative networks, community engagement, risk analysis, surveillance and monitoring, practice and experience, resources, workforce capacity, communication, and learning and evaluation. Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8 The “four S’s” Casiraghi adopted the theory of surge capacity. Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36

Adopted Thematic and Content Analysis Approach—The significant learning opportunities within the three major disaster types encountered in included articles were analyzed in two sections, including four themes adapted from a hybrid method developed by Ali, Desha. Reference Ali, Desha, Ranse and Roiko26 This model merges the essential elements of the Hospital Safety Index (HSI) and Pan America Health Organization (PAHO) that should be included in evaluating hospital resilience Reference Ali, Desha, Ranse and Roiko26,Reference Murshid, Riaz, Islam and Haque37,Reference Sunindijo, Lestari and Wijaya38 as follows:

-

- The functional/operational section (staff/HCWs; system/emergency and disaster management).

-

- The physical section: non-structural safety elements (eg, architectural safety, infrastructure protection, critical systems, equipment, and supplies) and structural safety elements (eg, building integrity and previous occasions and dangers affecting building safety).

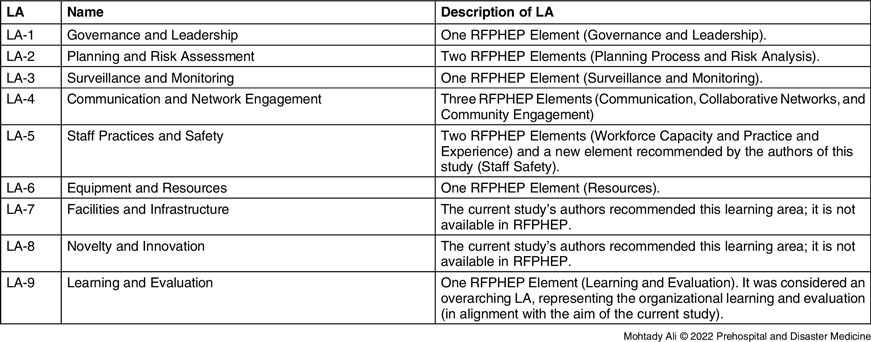

A content analysis was applied within each theme based on nine learning areas (LAs). These LAs were developed by adapting the RFPHEP and represent the different learning opportunities that emerged in the hospitals during or after disasters (Table 1).

Table 1. The Nine Learning Areas (LAs) and Their Description

Abbreviations: LA, learning area; RFPHEP, Resilience Framework for Public Health Emergency Preparedness.

Results of Thematic and Content Analysis of the Included Studies

Staff/HCWs—The findings in this study indicated several stressful factors affecting the physical and mental wellness of the hospital HCWs. During the Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone (2014), HCWs suffered from being infected, isolated from their families, having trauma due to observing their colleagues’ death, struggling with an increased stress and workload, as well as a trust breakdown between them and their neighbors/communities (LA 5). Reference Raven, Wurie and Witter39 Similarly, Hurricane Sandy (2012) led to considerable psychological stress for the majority of the HCWs following the destruction of homes, loss of power, evacuation, and lack of water and food (LA 5-7). Reference Toner, McGinty and Schoch-Spana40

Disasters such as Hurricane Harvey (2017) or the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic confused and frustrated the staff, who questioned the systems’ inconsistency in initiating the emergency response, their hospitals’ disaster response capability, and the frequently changing delivery care policies (LA 1). Additionally, staff were left without assurances in the dark, hearing gossip about the expected patients’ surge, and insufficiency of resources and PPE (LA 4 and LA 6). Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8,Reference Ybarra10

Significant resilience of HCWs was demonstrated in stressful infectious diseases working conditions (LA 5). Reference Walton, Navaratnam, Ormond, Gandhi and Mann34,Reference Raven, Wurie and Witter39,Reference Balay-odao, Alquwez, Inocian and Alotaibi41 Besides, their age, experience, and confidence in public health authorities contributed positively to their resilience (LA 5). Reference Toner, McGinty and Schoch-Spana40 The HCWs’ coping strategies during disasters included their sense of duty, religion, family and peer support, resources availability, and the risk allowance motivation (LA 1 and LA 6); communication platform availability (LA 1, LA 3, and LA 4); and orientation, training, and workshops boosting the staff’s confidence and performance regarding their conjoined stigma (LA 5). Reference Ybarra10,Reference Drevin, Alvesson, van Duinen, Bolkan, Koroma and Von Schreeb16,Reference Raven, Wurie and Witter39–Reference Yi-Feng Chen, Crant and Wang42 For example, during the Ebola outbreak, caesarean section surgery continued at Sierra Leone public hospitals due to the intrinsically motivated staff performing this surgery, despite infection risks and stigmatization (LA 5). Moreover, the staff surgery performing capacity increased by hospital support from non-governmental organizations and the World Health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland) agencies that provided the PPE, sterilization equipment and diagnostics, and facilitated the infection prevention and control implementation (LA 1 and LA 6). Reference Drevin, Alvesson, van Duinen, Bolkan, Koroma and Von Schreeb16

The terroristic attack in Norway and Mumbai underlined the need for public hospital strengthening. It highlighted the significance of HCWs’ continuous training and education in providing them with the experience, knowledge, and skills required for making rapid decisions enduring extreme situations (LA 5). Reference Brandrud, Bretthauer and Brattebø30,Reference Roy, Kapil, Subbarao and Ashkenazi43

The novelty was profound during disasters as hospitals’ clinical teams and staff members continuously created profound innovative ideas (LA 5 and LA 8) and practical problem-solving strategies in dealing with and coping with challenges (eg, patient surge and lack of PPEs, treatment protocols, or caring plans [LA 2 and LA 6]). Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8,Reference Cariaso-Sugay, Hultgren, Browder and Chen31,Reference Singh, Coker and Vrijhoef44 Changes and modifications of official hierarchies empowered the clinical staff care delivery in the face of uncertainty and allowed them to adopt an “all hands on deck.” Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8 The existing areas were converted into isolation sections, employees were redistributed to other work areas, supplies and equipment were strategically detailed, and educational endeavors were initiated (LA 3, LA 5, LA 6, and LA 8). Reference Cariaso-Sugay, Hultgren, Browder and Chen31 In the same way, some nurse leaders responded to COVID-19 in novel ways and swayed from normal operations. Hence, a nurse manager labelled the suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases as “blue patients” as an innovative strategy to keep patient confidentiality (LA 5 and LA 8). Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8 In addition, extraordinary clinicians and nurses collaborated to develop a flow chart and separate lanes for better patient management (LA 4 and LA 8). Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36

System/Emergency and Disaster Management—Concerning COVID 19 emergency response, a great significance of well-defined leadership, flexibility, and robust communication methods in responding to ever-changing clinical situations were reported in the UK (LA 1 and LA 4). Reference Walton, Navaratnam, Ormond, Gandhi and Mann34 Moreover, there was a genuine need for more communication in the US regarding policies, resources, patient management, and family visits (LA 4), as well as for continuous monitoring and evaluation of the disaster plans regarding the infected cases numbers; staff needs, safety, education and training, infection prevention compliance, and surveillance; and resources and patient care delivery (LA 2 and LA 3). Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8 Similarly in Singapore, a lack of a shared definition and decision making of surge threats led to replicating procedures (LA 1). The management was honest, reflecting their transparency principles (LA 1). Nevertheless, the top-down communication flow and instructions from authoritative persons to assigned members were inapplicable and unsuccessful (LA 4). Reference Singh, Coker and Vrijhoef44

Many challenges were reported in the literature. Reference El Sayed, Chami and Hitti1,Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8,Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36,Reference Gao, Wu and Li45 Flooding in the UK caused health care disruption and, hence, institutional challenges in recognizing vulnerable and at-risk individuals. These effects highlighted the limited health care system preparedness and response capacity to the future changing climate risks (LA 2). Reference Singh, Coker and Vrijhoef44,Reference Landeg, Whitman, Walker-Springett, Butler, Bone and Kovats49 The challenges in a terroristic attack in Beirut included three significant areas: an enormous influx to the emergency department of patients before plan activation, non-essential personnel, family members, and media personnel at the department entrance (LA 1 and LA 8); delay in plan activation and medical supplies deployment (LA 2 and LA 6); and inefficiency or inadequacy of patient registration, paper-based information systems, coordination, existing patients managing, and personnel roles due to ambiguity (LA 3-5). Reference El Sayed, Chami and Hitti1

Hospital decision makers fulfilled the effective health crisis response measures and needs in various ways; for instance, by increasing the staff in the incident command center (LA 5) and sharing planning experiences with the scientific community (LA 1 and LA 4). Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8,Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36

In Saudi Arabia, the hospital preparedness and response were based on the urgent governmental and public health authorities’ actions and adequate funds allocation. These actions led to hospital readiness and compliance with the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, Georgia USA) policies and procedures; staff, medicines, and equipment availability; and staff, patients, and visitors’ safety (LA 1, LA 5, and LA 6). Reference Balay-odao, Alquwez, Inocian and Alotaibi41 Hospital resources represented one of four factors that contributed widely to the hospital’s total disaster resilience ability (LA 6). Other factors included hospital safety, hospital disaster medical care capability, and hospital disaster management mechanism (LA 1 and LA 7). Reference Zhong, Hou and Clark11

Organizational Learning and Evaluation (LA 9)

During the SARS outbreak in Singapore, a learning opportunity stemmed from the lack of daily essential hospital supplies and PPEs and led to an enhancement in equipment and stockpiling preparedness since then (LA 6). Hence, when the next pandemic of Swine Flu struck, these resources were ready and accessible, and several hospitals autonomously stored PPEs and drugs for at least three days to have enough time to reorder in any sudden surge in Singapore (LA 1, LA 2, and LA 6). Reference Singh, Coker and Vrijhoef44

Italy suffered a high number of COVID-19 deaths among doctors, and many surgeons felt exposed to infection with an increased risk as the PPE supply was sometimes insufficient (LA 3, LA 5, and LA 6). For example, the Spedali Civili, one of the biggest hospitals in Italy, was highly impacted by COVID-19 infection. However, in its trauma hub, the organization and operational strategies of trauma service provided the health workers with all the mandatory PPE, and no new cases of infection were documented between the doctors and nurses in orthopedic wards and operating rooms (LA 3, LA 5, and LA 6). In addition, they had a well-defined strategy and protocols that supported the systems’ resilience and guided the staff members towards effective and high-quality care delivery (LA 1, LA 2, and LA 6). Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36

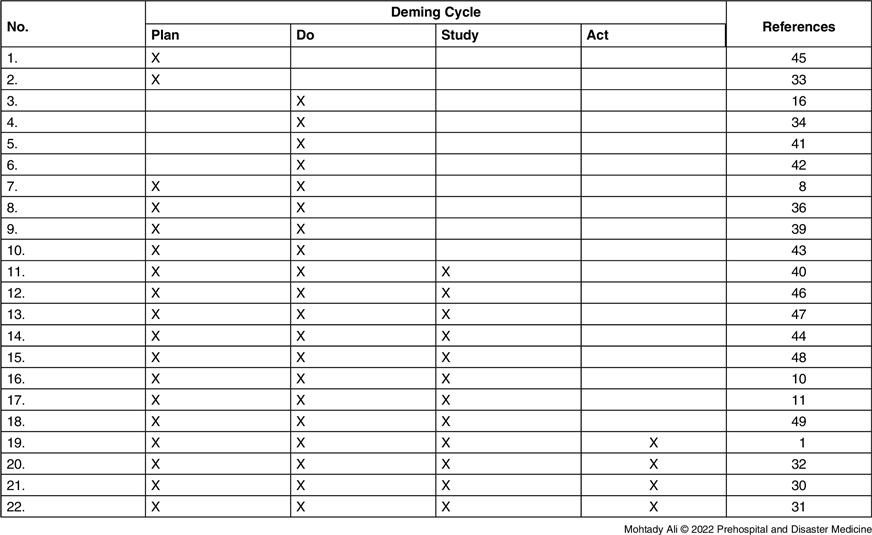

The Deming cycle PDSA addressed the hospitals’ organizational learning in the included studies. Most of the studies completed either two or three stages of the Deming cycle. Out of 22 studies, eight conducted the first three Deming stages (PDS) with no further actions implemented. The remaining ten studies were either for one or two stages (P and/or D). Moreover, only four studies completed the entire Deming cycle (PDSA). These four studies adopted different approaches. For example, one of these studies included open-ended questions in the post-intervention survey to depict participants’ feedback and improve future interventions targeting disaster management as a part of the Quality Improvement project. Reference Cariaso-Sugay, Hultgren, Browder and Chen31 This evidence-based educational leadership training aimed to enhance the disaster management knowledge and confidence of 50 nurse leaders to promote resilience, support of employees, and optimal patient outcomes. The results reported significant perceived knowledge and confidence development, with 33 participants completing the post-intervention survey. Hence, the nurse leaders were challenged to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in novel ways by varying their routine operations. In another study, the hospital planners learned from an earthquake experience and utilized it to complete the continuous improvement cycle. Thus, following the earthquake, they incorporated the recommendations developed by the hospital planners as a part of the hospital’s daily activities and monthly meetings of the Emergency Preparedness Committee. These actions eventually enhanced the hospital system’s resilience to future disasters. Reference McDaniels, Chang, Cole, Mikawoz and Longstaff32

Similarly in Lebanon, an analysis, summarizing, and debriefings were done following the terroristic MCI event to modify the hospital’s disaster preparedness plan. Reference El Sayed, Chami and Hitti1 Finally, the fourth study addressed the success of the Emergency Medical Services in the local community hospital. Three external bodies evaluated it as successfully dealing with a terroristic attack in Norway. The study showed that the success elements included, but were not limited to, emergency preparedness and competence based on continuous planning, training, and learning. In addition, the involved hospital was one of “the pioneers in team training as part of a continuous quality improvement system.” Reference Brandrud, Bretthauer and Brattebø30 Analysis of the finally included articles using the Deming cycle is presented in Table 2. Reference El Sayed, Chami and Hitti1,Reference Aliyu, Norful, Schroeder, Odlum, Glica and Travers8,Reference Ybarra10,Reference Zhong, Hou and Clark11,Reference Drevin, Alvesson, van Duinen, Bolkan, Koroma and Von Schreeb16,Reference Brandrud, Bretthauer and Brattebø30–Reference Walton, Navaratnam, Ormond, Gandhi and Mann34,Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36,Reference Raven, Wurie and Witter39–Reference Landeg, Whitman, Walker-Springett, Butler, Bone and Kovats49

Table 2. Analysis of the Finally Included Articles (n = 22) using the Deming Cycle

Discussion

Organizational Learning and Evaluation in Hospital Disaster Management

The findings in the current study showed that only four out of 22 studies completed the Deming cycle (PDSA) and ensured their insights were translated into action. These findings highlighted a gap in conducting continuous quality improvement following a disaster.

During disasters, hospitals’ immediate response is facilitated by their existing organizational structures. However, most of them return to their routine activities once the catastrophe is ended. Thus, the knowledge that might be realized by reflective processes are missed. The incomplete learning cycle could be due to a lack of proper mechanisms for debriefing, under-estimating the value of sharing experiences, and reluctance to apply the prior experience and evaluation. Reference Gao, Wu and Li45

Organizational learning happens when experiences are transformed into beneficial changes in the organization’s collective knowledge, cognition, and actions. Thus, the organizational environment is critical to such learning. Reference Lyman, Hammond and Cox50 The concept of organizational learning is ascribed to developing the “active learning” approach, which employs small groups, rigorous statistical data gathering, and harnessing the group’s positive emotional energy. Reference Garratt51 This approach is also used in Deming’s quality control system, employing quality circles and statistical process control. Reference Wang and Ahmed52 Similarly, in the resilience engineering approach, four categories of capabilities were defined, comprising: (1) Actual (to respond to events); (2) Critical (to monitor on-going developments); (3) Potential (to anticipate future threats and opportunities); and (4) Factual (to learn from past failures and successes). Reference Pariès, Wreathall, Hollnagel, Wreathall and Hollnagel25

Learning is a continuous process in an organization, such as a hospital. Organizational experiences are transferred from internal staff and external stakeholders and continuously converted into knowledge to improve organizational performance. Reference Argote and Miron-Spektor53

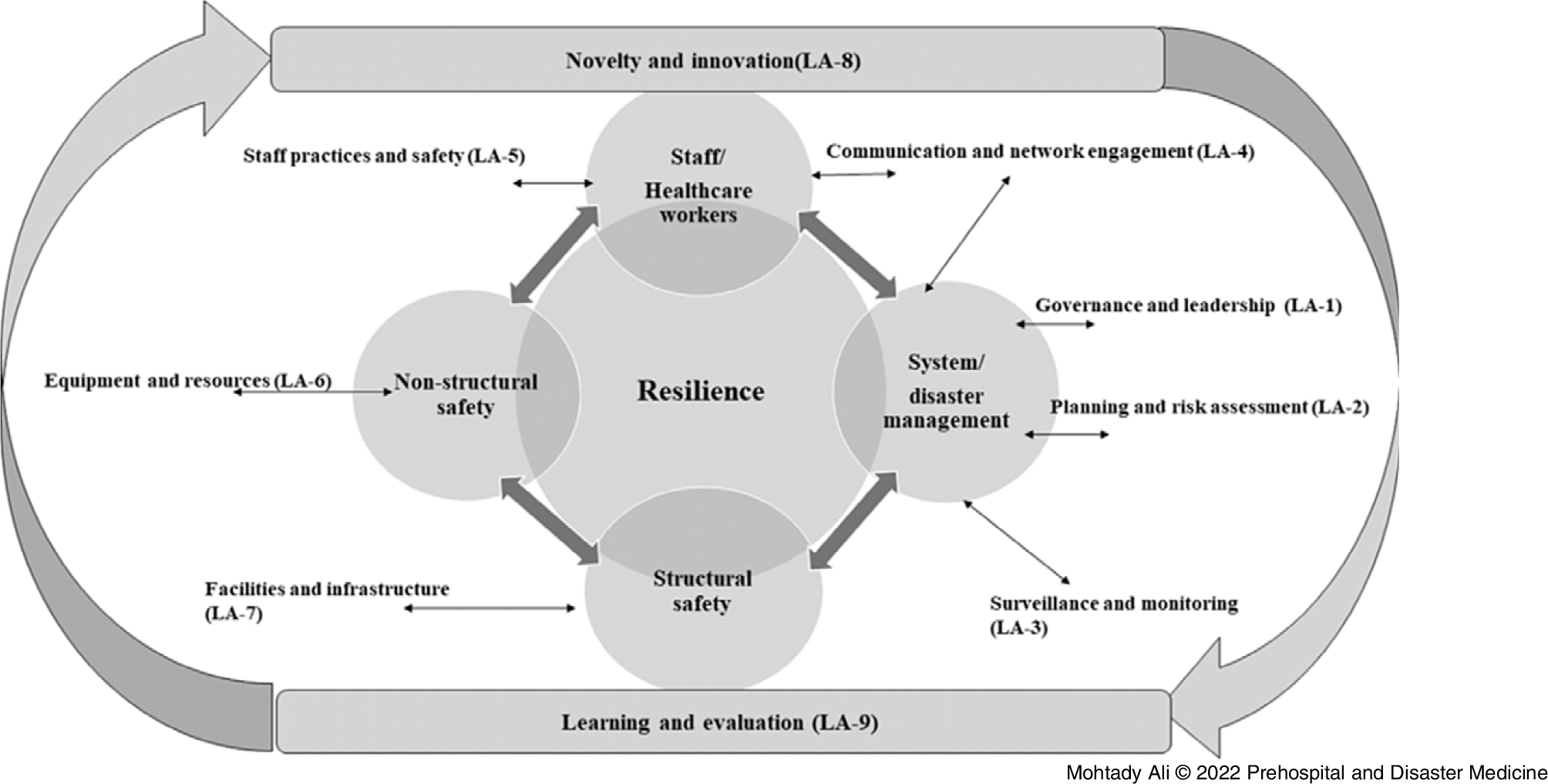

The current study portrayed the hospitals’ learning opportunities triggered by disasters and identified shared experiences for success and failure. The frameworks and theories adopted in the included literature were identified. The RFPHEP was modified into nine disaster learning areas used in the literature content analysis. Reference Khan, O’Sullivan and Brown35 Moreover, this process led to describing the most significant recommendations emerged from hospitals’ battles with disasters (Supplementary Table 6; available online only). Besides, a Hybrid Resilience Learning Framework (HRLF) was proposed for evaluating both organizational resilience and learning from disasters in this study. This HRLF was developed by enhancing the adopted RFPHEP framework and integrating it with the Hybrid Method for Hospital Resilience Assessment. The latter included the main sections of the HSI and PAHO (Figure 2). Reference Ali, Desha, Ranse and Roiko26,Reference Khan, O’Sullivan and Brown35

Figure 2. Hybrid Resilience Learning Framework (HRLF) for Evaluating Resilience and Organizational Learning Following Disasters.

Note: Adapted from the RFPHEP Reference Khan, O’Sullivan and Brown35 and the Hybrid Method for Hospital Resilience Assessment. Reference Ali, Desha, Ranse and Roiko26

HCWs’ Safety and Wellness

Disaster management entails complex processes and systems and mandates a balanced approach to guarantee seamless patient care delivery and rigorous staff safety measures. Reference Ybarra10,Reference Casiraghi, Domenicucci and Cattaneo36 Unfortunately, during real-life disasters, such balance is scarcely occurring. Reference Landeg, Whitman, Walker-Springett, Butler, Bone and Kovats49 The findings in this study indicated several stressful factors affecting the physical and mental wellness of the hospital staff and HCWs; some of these stressful factors are unlikely to be preventable. Meanwhile, there were other compensating mechanisms as rejuvenating coping strategies. Hence, to ensure the HCWs’ physical safety and mental wellness, hospital decision makers should be able to create a balanced approach between both stressful and rejuvenating factors. A summary of these factors was conceptualized in this study (Figure 3).

Figure 3. HCWs’ Safety and Well-Being, The Stressful and Rejuvenating Factors.

Abbreviation: HCW, health care worker.

Limitations

The selection of original peer-reviewed, English articles limited the included articles. The excluded research studies written in other languages and the excluded non-peer-reviewed articles could have valuable information to inform hospital disaster resiliency. A limitation of the study is the lack of outcome for hospitals and systems described in the literature when presented with a second disaster event or full functional testing of preparedness and resilience. Most of the literature and findings are theoretical in nature.

Conclusion

Drawing messages from disaster management is crucial for hospitals’ resilience in future crises. Following a thematic analysis of the findings, nine hospital learning areas were developed for content analysis. However, there is a gap in hospital application of prior experience and knowledge. Additionally, this study highlighted that the hospital decision makers must empower, guide, and motivate all HCWs by considering stressful factors and coping strategies. Hence, the authors proposed a “Hybrid Resilience Learning Framework” to evaluate resilience and organizational learning following disasters.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Acknowledgment

The corresponding author is a recipient of the Griffith University PhD scholarship (Postgraduate Research scholarship) and a Griffith University International Postgraduate Research scholarship.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X2200108X