He looked to the south, and regarded her feelings, in every vote which he was disposed to give.

—Opponent of Black SuffrageHe should regard all those who voted to deprive the colored man of [suffrage] as a friend of slavery.

—Supporter of Black SuffrageFootnote 1Between 1865 and 1870 the United States embarked on one of the most radical projects of democratization in world history (Valelly Reference Valelly2016; Du Bois Reference Du Bois1935; Foner Reference Foner1988). The decision to enfranchise millions of African American men had roots in the efforts of newly free persons to secure their emancipation, in the determination of some whites to eradicate the “slave power” they blamed for the Civil War, and, critically, in the political exigencies confronting the Republican Party as it sought to institutionalize a new regime and its own political primacy (Valelly Reference Thurston2004; Wang Reference Valelly, Valelly, Mettler and Lieberman1997).

I offer a new perspective on the developments that preceded this democratization, enriching our understanding of two of the most important and enduring issues in the study of American politics: the extension and contraction of voting rights and the development of America’s racial orders (King and Smith Reference King and Smith2011). I argue that over the first half of the nineteenth-century African American political rights went from being a relatively non-partisan issue to one of the most polarizing questions of the era. This process has to date received relatively little notice,Footnote 2 with most historical accounts either neglecting this dimension of conflict or portraying a stable pattern of partisan positions. As David Walker Howe has summarized the literature, “the issue of black suffrage consistently divided the political parties: Federalists supported it and Jeffersonians opposed; Whigs supported it and Jacksonians opposed” (Howe Reference Howe2007, 497-98; Budros Reference Budros2013, 389).

I draw on new data on state politics to identify an important transformation in how legislators’ votes mapped on to party affiliation and the structure of ideological conflict, recovering the pro-suffrage positions of early Jeffersonians and Democrats, documenting a subsequent process of issue-sorting along party lines, and placing support for black voting rights within the mainstream of the Republican Party at an earlier date than is usually appreciated. These findings substantially expand our descriptive understanding of the ideological and partisan connotations of black political rights in the nineteenth-century, and constitute the first systematic account of the development of partisans’ positions on this issue before the Civil War.

I also provide a new interpretation for this development, one that builds on existing accounts of franchise reforms (Valelly Reference Thurston2004; McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2015; Teele Reference Stewart2018a) but which focuses on competing efforts to define the terms of national community. The most common explanation for partisan differences on black suffrage is a narrow electoral calculation made by party leaders about the potential voting strength of African Americans, with reforms to the franchise treated as party-driven efforts to prioritize their collective electoral interest (Polgar Reference Piven, Minnite and Groarke2011; Malone Reference Malone2007). As one Ohio Democrat put it, “every negro in Ohio is a Whig and if he is allowed to vote, the Whigs will get a great accession of strength. The Whigs have too many voters now” (Smith Reference Sinha1851, 637).

Instead of asking why the parties pursued or opposed black suffrage, I ask why the thousands of individual legislators who voted on the issue took the positions they did, and how their diffused choices impacted the party system. While calculations about the electoral consequences of black voting could be important, these were only one of several factors influencing individual vote choices, and not usually determinative. I instead provide statistical and qualitative evidence that legislators’ positions were responsive more to competing efforts of party leaders and social movements to frame the denial of free black suffrage as important for national unity, a necessary accommodation to racist white public opinion, or as complicity in human slavery and a violation of republican commitments. These last framings were advanced as part of a decades-long effort by free African Americans and whites in the antislavery movement to redefine the character of American citizenship. It was their efforts, and the fierce backlash against them, that placed black suffrage on the political agenda, drove partisan sorting on this issue, and laid the foundation for the democratizations of Reconstruction.

These findings have important implications for our understanding of American history and contemporary politics. One is simply that we should reevaluate the relative contribution of social movement activism, ideological commitments, elite interests, and partisan calculations for the extension and restriction on voting rights. The enfranchisement of African American men during Reconstruction is rightfully treated as the paradigmatic case of strategic enfranchisement, a party-driven expansion of the right to vote intended to stave off a looming electoral threat (Valelly Reference Thurston2004). But the earlier process of contestation over black voting rights, most of which occurred in northern states with relatively few free men of color, is more reflective of what Corrine McConnaughy (Reference McConnaughy2015) has described as a programmatic model of suffrage reform, in which organized interests or third parties pursue an alteration of the franchise because it aligns with their own policy goals. Instead of adjudicating between different models of franchise reform, I point toward a productive synthesis: integrating the earlier period of disenfranchisement and antislavery activism recasts the party-driven extension of voting rights as the culmination of a long process of biracial social-movement organizing, enhancing our understanding of how both electoral and programmatic concerns contribute to reforms.

A second implication concerns the development of America’s racial orders, encompassing the construction of racial civic status as well as the configuration of politics around race (King and Smith Reference King and Smith2011). The disenfranchisement of free black Americans at the beginning of the nineteenth century was part of a process by which the category of “citizen” was narrowed to encompass white men alone, even as public policy was being deployed to create a racially exclusive territorial empire (Frymer Reference Frymer2016); the decades before the Civil War, however, saw the beginning of a sustained effort to reenfranchise black men and affirm their status as equal citizens (Jones Reference Jones2018). During this period, the issue of black political rights went from being tangential to the party cleavage to the subject of repeated fights that deeply polarized the parties.

The contradicting legacies of these processes have long shaped the content of our collective life, and continue to do so today. The study of the pre-Civil War partisan realignment over race, for instance, offers a companion to studies of position change on black civil rights during the twentieth-century (Schickler Reference Schattschneider2016; Karol Reference Karol2009; Carmines and Stimson 1989) and foreshadows contemporary patterns of partisan polarization: the antebellum era is the only other period in American history in which positions on racial policy questions mapped on to the party cleavage (King and Smith Reference King and Smith2011, 11). By better understanding the causes of this polarization, we gain not only a firmer grasp of how white supremacy was established and contested but of how conflict over the boundaries of citizenship has at times become the central cleavage in American politics.

Black Suffrage in America

The emergence of black suffrage on the agenda during Reconstruction often appears as a logical progression of the Civil War, as the effort to preserve the Union led to the abolition of slavery, which led to legal protections for freed black Americans, which led to the recognition that only through the ballot could their rights—and Republican political power—be secured. In reality, the issue of black political rights had been a recurring subject throughout the early-Republic and antebellum eras, an at-times vitally important site of contestation over the boundaries and character of American citizenship.

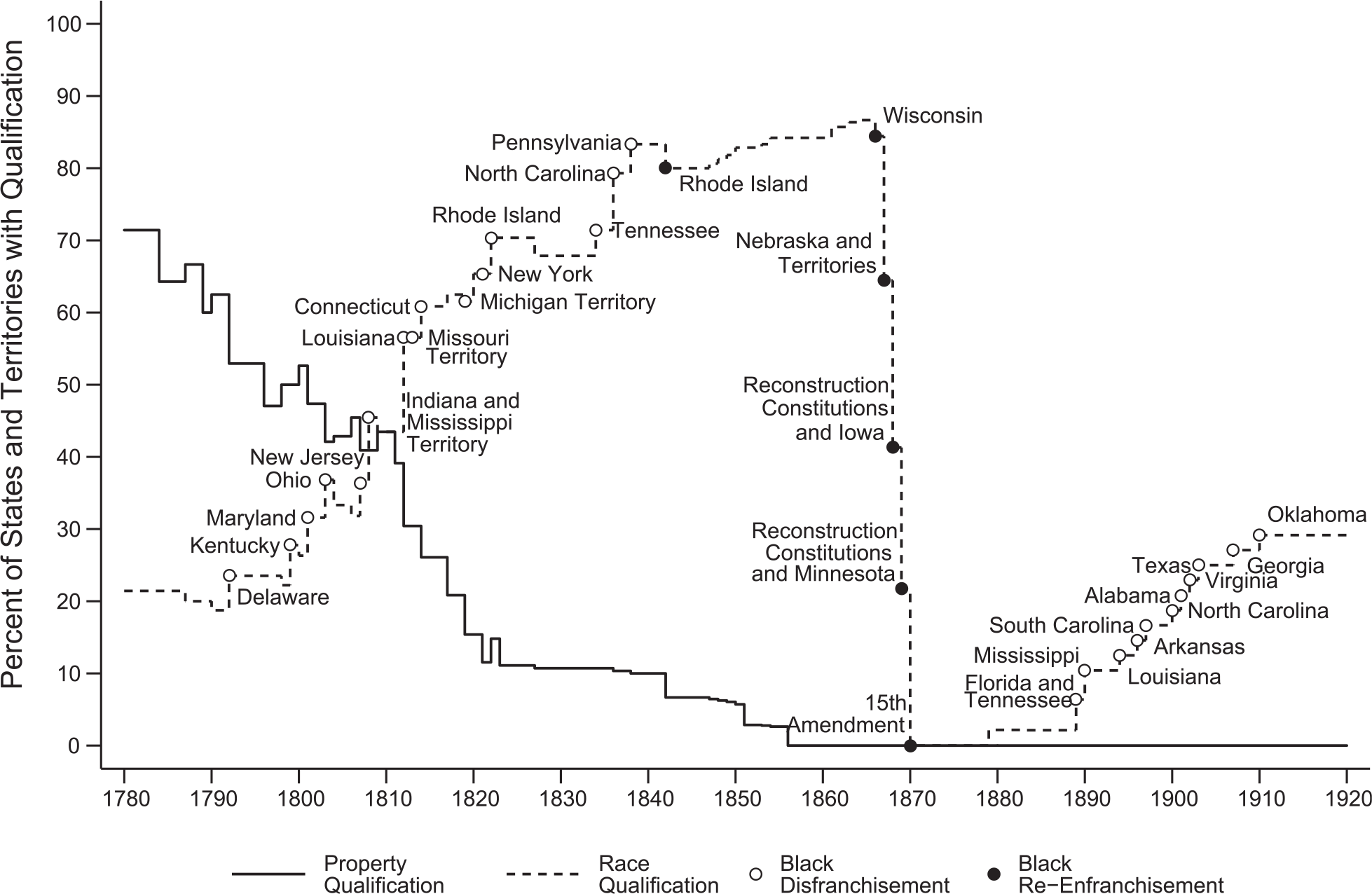

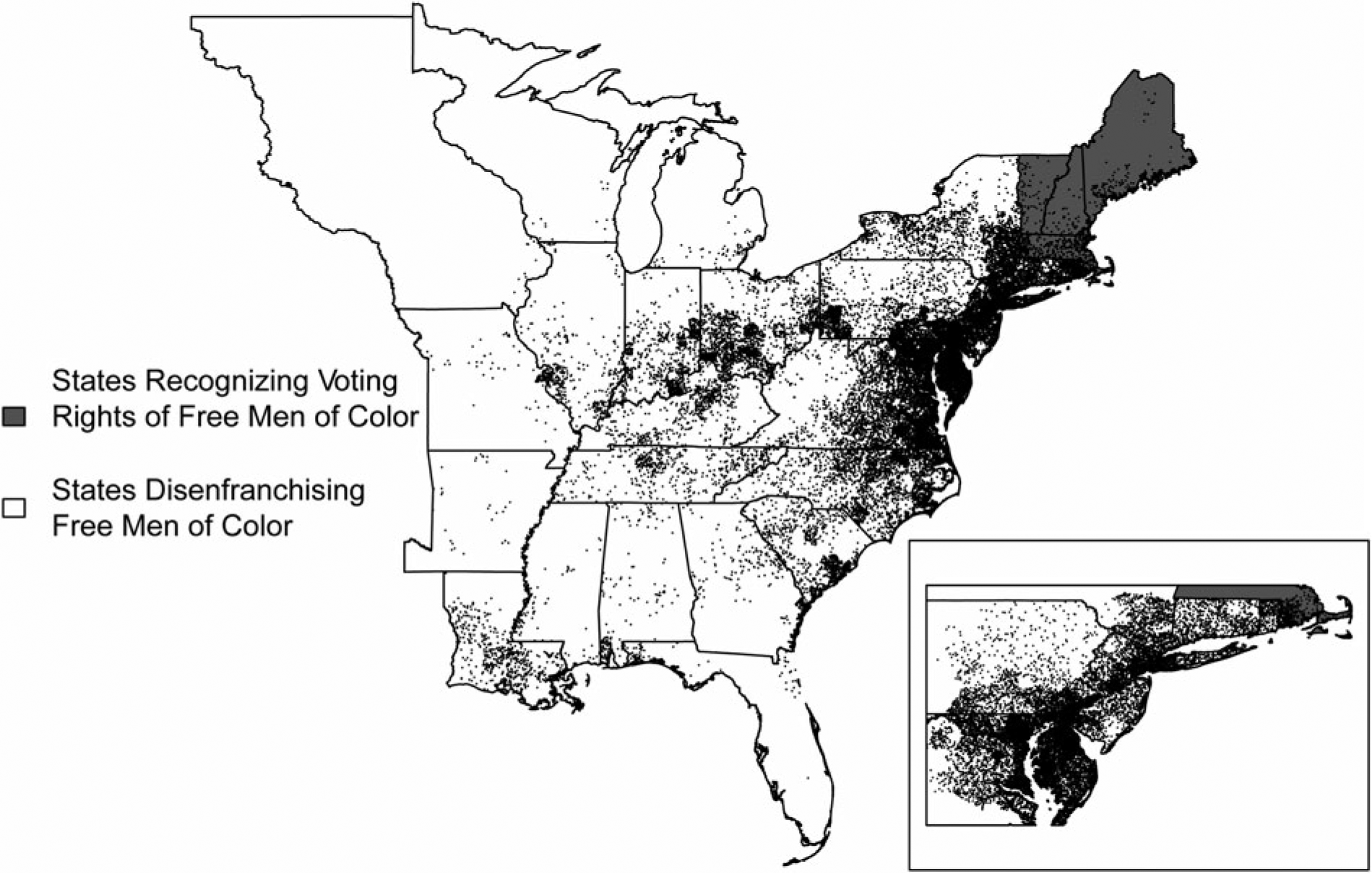

Figure 1 shows the development of the male suffrage between 1780 and 1920.Footnote 3 African American voting was a controversial issue as early as the 1780s, and by the first decade of the nineteenth century black men were voting in several mid-Atlantic and New England states (Polgar Reference Piven, Minnite and Groarke2011; Bogen Reference Bogen1991). Over the next few decades, however, legal disenfranchisements gradually pushed these growing communities from the electorate, so that by 1840 equal voting rights were recognized in only four New England states, with New York enfranchising only a small number of wealthy men (Figure 2).Footnote 4 The United States was being redefined as a “white man’s republic,” with the vast majority of the non-white population either enslaved or free but with shrinking rights.

Figure 1 Qualifications for Male Voting

Figure 2 Geographic Distribution of Free Persons of Color, 1840

The 1840s, however, inaugurated a new phase in the fight over voting rights. Rhode Island re-enfranchised black men in 1843, as local Whigs dropped their opposition to equal rights in order to secure the support of the free black community during the “Dorr War” (Chaput Reference Chaput2012). Over the next two decades dozens of states debated constitutional amendments to strike the word “white” from their qualifications, with several holding referenda on the question.Footnote 5 With the exceptions of Rhode Island and Wisconsin—where most opponents did not vote, in the latter case leading to the result being set aside—these were resoundingly defeated. After the Civil War, racial qualifications were abolished in a few Republican-controlled midwestern states and then by order of Congress in the territories and District of Columbia, by congressional action and biracial conventions in the Reconstruction states, and finally across the country through the Fifteenth Amendment. At century’s end, however, African Americans in the South would be largely disenfranchised through qualifications explicitly justified as targeting black voters (Kousser Reference Kousser and Morgan1974). America had begun to democratize, only to see the gains of the mid-nineteenth century clawed back.

Political Parties and Voting Rights

Explanations for these changes have long given primary importance to the electoral calculations of political parties, whose leaders have seen in black Americans a potential constituency whose votes could tilt electoral outcomes (Polgar Reference Piven, Minnite and Groarke2011; Malone Reference Malone2007; Valelly Reference Thurston2004; Kousser Reference Kousser and Morgan1974). The logic of electorally motivated changes to voting qualifications—what Richard Valelly and Corrine McConnaughy have termed “strategic enfranchisement” (Valelly Reference Valelly2016; McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2015, 34)—is an elaboration of the premise that the primary objective of politicians is to win office, with political parties the vehicles for the realization of this objective (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974; Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995). If in power and threatened with defeat, parties might choose to enfranchise new voters (Schattchneider 1964, 101) or disenfranchise those who support their rivals. Party-driven accounts need not presume that all legislators are motivated solely by winning office; and the activism of the disenfranchised can reinforce the incentives of electorally-calculating parties by providing a mobilizing infrastructure that might be used in future elections (Teele Reference Stewart2018a, Reference Teele2018b; Valelly Reference Valelly2016, 452). Still, positions on the franchise are generally explained by a collective partisan interest in winning elections.

In recent years a diverse literature has expanded our understanding of parties beyond a focus on ambitious office-seekers, reframing these as coalitions of organized policy demanders in which party leaders serve as reliable representatives of groups’ negotiated policy agenda (Bawn et al. Reference Bawn, Cohen, Karol, Masket, Noel and Zaller2012, 575). While parties in these accounts still pursue electoral success, they do so within the constraints imposed by their broader policy-oriented coalitions; the positions taken by legislators in turn reflect the party’s collective agenda, the advancement of which is their “paramount goal” (Bawn et al. Reference Bawn, Cohen, Karol, Masket, Noel and Zaller2012, 571). A policy-oriented coalitional perspective raises the possibility that partisan positions on black suffrage might have been motivated not by an electoral interest in black voting, but by the value that party-aligned groups’ found in facilitating or blocking the policy demands of black constituencies. This converges with a number of accounts in the literature on the franchise. In their study of voter suppression, for example, Frances Fox Piven, Lorraine Minnite, and Margaret Groarke argue that parties choose voter suppression over policy accommodations when the latter would threaten the core priorities of their coalition (2009). In a different vein, McConnaughy has argued that organizations representing already enfranchised constituencies might have a policy interest in expanding voting rights, because they anticipate that the new voters will support their priorities or because the disenfranchised are included in their own non-electoral constituencies (2015, 37).

But while political parties might have a collective interest in supporting a particular policy, the difficulties they will confront in pursuing this can be substantial: for this reason, theoretical accounts of parties often suggest that these organizations will delegate to party leaders the responsibility of defining the collective policy agenda that the party will advance and be associated with.Footnote 6 And yet there are important reasons to suspect that parties will not always be able to act as nimble entrepreneurs in pursuing opportunistic policy initiatives, nor that a collective interest in a policy will be sufficient to direct the energies of their members. Through most of American history the major political parties have been federated institutions based on state and local level organizations that retained considerable flexibility to pursue their own policy priorities and in which individuals could stake out distinctive positions on politically salient issues (McCarty and Schickler Reference McCarty and Schickler2018). National and state party leaders could try to manage these divergent priorities, and on some important issues they did try to enforce discipline. But the parties’ diffused character has always complicated top-down coordination: even if party leaders judged something to be in the collective interests of the party, individual legislators and factions had to balance this against their own preferences or ambitions, making them resistent to centralized dictation. And while legislators might have a shared interest in the party’s well-being, the parties’ national scope inevitably produces heterogeneous incentives across districts, encouraging individual lawmakers and local party organizations to take positions that contradict the collective party interest.

Individual Legislators and Programmatic Reform

Accounts of suffrage reform have long grappled with this feature of American parties, detailing the difficulties faced by policy entrepreneurs or party leaders in coordinating their fellow party members around changes to the law or constitution. An alternative approach is to start not with the interests of the parties—whether electoral or coalitional—but with the choices made by candidates and office-holders, putting individual partisans at the center of the story and examining how their diffused choices shaped an issue’s partisan and ideological connotations and, in turn, the constraints this imposed on party leaders. Instead of framing legislative voting on black suffrage as reflecting a deliberate party-driven effort to pass legislation, we can treat it as position-taking, a form of behavior in which individual legislators provide a public indication of where they stand on an issue of interest to attentive political actors (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974).Footnote 7

Treating legislator behavior as position-taking requires us to attend to what the legislators believed they were communicating and to whom. The intended audience could include party leaders, social and economic elites, activists in social movements believed to have valuable political resources (Schlozman Reference Schickler2015), or the preferences of a voting public. Individual legislators have to craft public positions that align their own goals with the intensity and direction of local public opinion, the priorities of influential elites, the ability of social movement activists to sway opinion or elections, as well as any inducements or signals from their party organizations. Legislators’ individual agency in doing so, however, positions them as potential intermediaries between party and nonparty groups. Approaching black suffrage through the lens of position-taking can accommodate the possibility that the parties were the principal actor without presuming they were, and provides a pathway by which the priorities of nonparty and even disenfranchised groups might be picked up by individual legislators and placed on the agenda, possibly even against the strategic calculations of party leaders.

During the antebellum era, there were at least three nonparty groups with strong preferences on black suffrage to which legislators had to be attentive. The largest was a white male electorate with a broadly shared, but varyingly intense, racism. A second and overlapping group were slaveholders, an influential elite centrally important to the leadership of national party coalitions but also a potentially pivotal voting constituency. Slaveholders were ferociously opposed to black suffrage, on the grounds that recognizing free black Americans as equal citizens would endanger the racial hierarchy they relied on for social control while incorporating a constituency that they expected would be opposed to slavery (Bateman Reference Bateman2018). Slavery could shape legislators’ position through elite influence but also via public opinion: it was a commonplace among abolitionists, for instance, that popular commitments to white supremacy were the product of the association of blackness and slavery.Footnote 8

Slaveowner influence and legislators’ expectations of a racist backlash would have cautioned against supporting equal voting rights. But in many districts legislators were subjected to a counter-pressure from organized abolitionist constituencies. The immediatist antislavery movement and local organizations of free African Americans were the only large-scale groups to explicitly endorse black suffrage in the antebellum era and to mobilize on its behalf. And while few legislators were responsive to free black Americans, they could not be so indifferent to white constituents who might amplify demands made by African Americans. Abolitionists were always a small minority among the northern white population; and into the 1860s a sizeable faction of legislators allied with the abolitionist movement preferred a country in which slavery had been abolished but with free persons of color removed (Frymer Reference Frymer2016). But its more radical factions engaged in extensive campaigns for racial equality in laws and to reform white public opinion (Yates Reference Wood1838, iv-v), and they formed the nucleus around which the antislavery Liberty and Free-Soil parties were organized.

These group- and constituency-based preferences could all shape a legislator’s vote choice, whether because the legislator desired reelection, was drawn from their ranks, or sought to fulfill a representative role. But most legislators were also part of organized political parties, with a collective interest in winning state- and nation-wide majorities. Even if individual lawmakers, because of their personal goals or particular features of their districts, could be unconcerned with the priorities of slaveholders or the racism of the electorate, their party’s leaders could not. For this reason, and in contrast to the implied symmetry of party-driven enfranchisement (Howe Reference Howe2007, 497-98), I argue that the leadership of all the national parties sought to persuade their members to vote against black suffrage before the Civil War. For Democratic leaders a responsiveness to racism could be buttressed by an electoral interest in excluding free black men. But even Whig and Republican party leaders, who would have benefitted from black votes, recognized that any perceived solicitude toward free black Americans placed considerable stress on their national coalitions or threatened their standing with a racist electorate.

This concatenation of partisan and nonparty priorities make the politics of black suffrage before the Civil War appear similar to what Corrine McConnaughy has called programmatic enfranchisement, which occurs “not as a consequence of a search for new supporters from the ranks of the disenfranchised, but in accommodation to the demands of existing voters,” such as organized groups or third parties, whose own interests, reliance on the resources or activism of the disenfranchised, or programmatic commitments make them willing to pursue reforms to the right to vote (2015, 37). While political parties play an important role in programmatic franchise reform, the analytical focus prioritizes other groups whose demands on legislators can lead to new issues being placed on the political agenda and to a sorting of legislators and parties around these.

Connecting the choices made by individual legislators with the programmatic efforts of nonparty groups helps bring into focus a different way of thinking about the relationship of the party system to political and civil rights, and thus of the relationship of the parties to the construction and transformation of American racial orders. While party positions can be motivated by efforts to win black voters (Carmines and Stimson 1989) or appeals to a racist white median voter (Frymer Reference Frymer1999), they can also be produced by the efforts of organized interests and social movements to target individual legislators. The result of this diffused process could be support for African American civil rights cutting across party lines, with individual legislators and factions serving as the vehicle by which competing positions on racial policy questions are integrated into both parties. But it might also result in a policy position becoming associated with a particular party, providing “racial policy alliances” (King and Smith Reference King and Smith2011) with influence within the party and an opportunity to redefine the ideological connotations of a particular racial policy question. Party positions on issues central to America’s racial order, including voting rights, accordingly appear less as a function of top-down “party” calculations than of diffused choices made by party members in response to local activism, public opinion, and organized interests (Schickler Reference Schattschneider2016).

Black Suffrage in the Historical Record

Understanding positions on black suffrage requires us to examine the motivations of thousands of individual legislators, whose votes and speeches defined the issue’s ideological and partisan connotations. The analysis presented here relies on case studies of constitutional conventions and legislatures, as well as newly assembled datasets of state legislative politics and county- and town-level data on voting in black suffrage referenda.

At its core is a descriptive analysis of how legislators voted and how these patterns varied across constituencies. What I believe to be every recorded roll call on black suffrage in the states from 1780 to 1865, as well as those from Congress to 1869, has been included in a dataset of vote choice, with the partisan affiliation of thousands of members located through searches of local newspapers and estimates of individual ideal points produced using the remaining non-suffrage roll calls (Clinton, Jackman, and Rivers Reference Clinton, Jackman and Rivers2004). These were merged with district-level demographic and political data,Footnote 9 allowing us to trace the probability of voting for black suffrage over time and space, and to construct a statistical model estimating the relative importance of district-level factors in shaping legislators’ vote choice.

Analyses of nineteenth-century legislative behavior are limited by the lack of data on public opinion. The expectations of group preferences discussed earlier, however, can inform the selection of variables and specification of the statistical model, allowing us to make preliminary evaluations of the relative importance of partisan calculations and the demands of nonparty groups. If legislators were responsive to the organized antislavery movement then we should expect that the vote for the Liberty and Free-Soil parties would be positively correlated with voting in favor of black suffrage. This is supplemented by the use of county- and town-level data on black suffrage referenda to empirically evaluate how mass preferences on this issue varied across party.

The data provides no information on how representatives perceived the issue of black suffrage, nor does it allow us to evaluate the importance of non-district factors. To complement the analyses of vote choice, detailed case studies were prepared of every instance of black disenfranchisement and legislative fight over black re-enfranchisement, drawing on contemporary newspapers, archival research, and secondary sources.

I use this data to ask three questions: (1) how did voting on black suffrage map on to the partisan and ideological structure of American politics; (2) what characteristics about the legislator and their district made taking a position in favor of voting rights more likely; (3) and what can be inferred about legislator motivations by tracing the process of legislative debate? I do not presume that there was a single motivation across all legislators, nor am I seeking to causally identify the determinants of legislator vote choice. The research design instead triangulates across distinct sources of evidence (Rothbauer Reference Renda, Cimbala and Miller2008), expanding the number of theoretically relevant observations in order to better evaluate the relative importance of different causes.

The Development of Positions on Black Suffrage

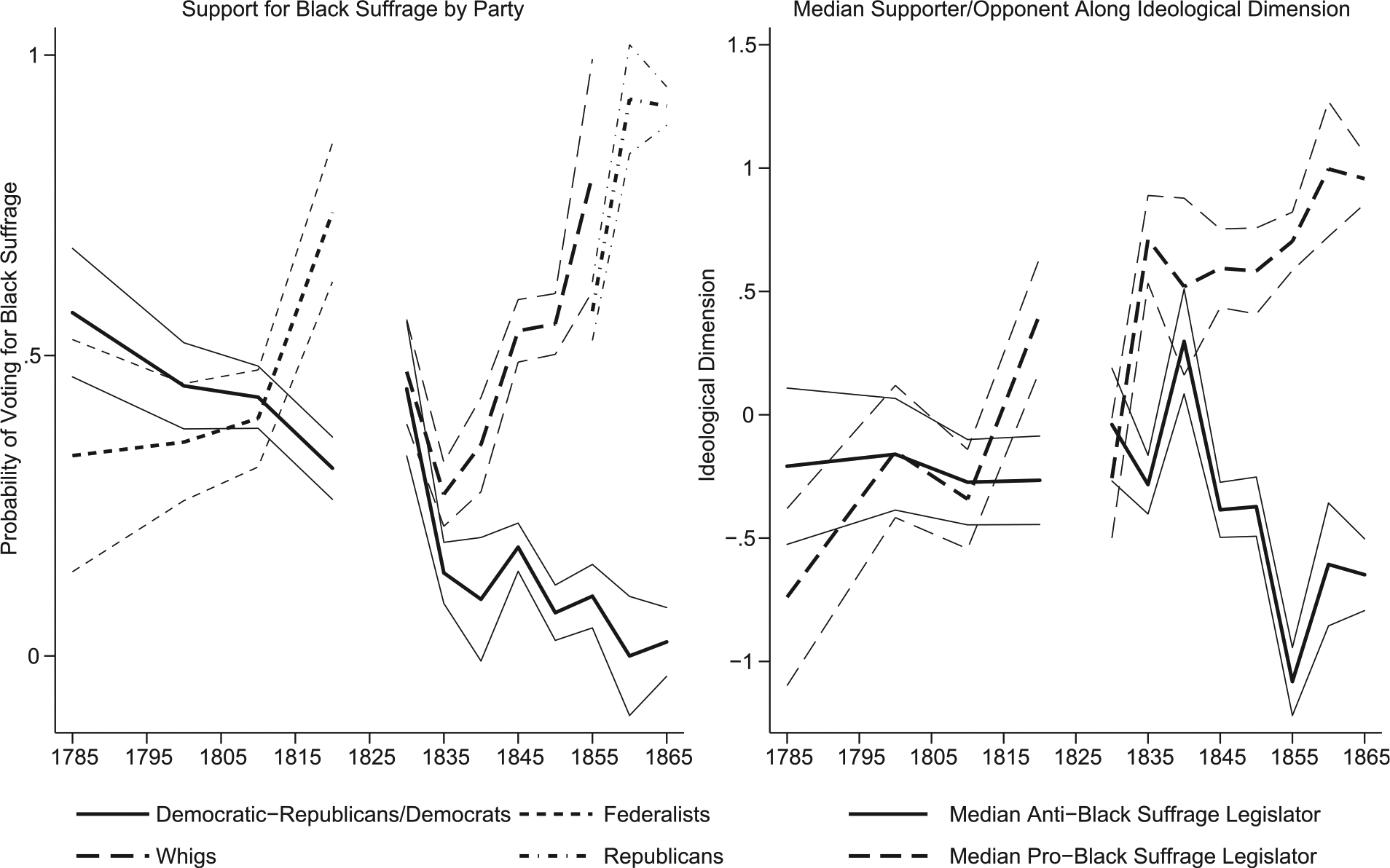

I begin by tracing the development of partisans’ positions on black suffrage over time, examining how voting on black suffrage related to party affiliation and ideology. To do so, I estimate the probability that a legislator would vote for black suffrage given their party affiliation and state in which the vote is being held.Footnote 10 These are shown in the left panel of figure 3.

Figure 3 Legislator Positions on Black Suffrage in Early Republic and Antebellum Eras

The first wave of black disenfranchisement in the early Republic was largely undertaken by legislatures with Jeffersonian majorities, and existing research argues that this was because Jeffersonians calculated that they would gain by excluding a largely-Federalist constituency (Polgar Reference Piven, Minnite and Groarke2011; Malone Reference Malone2007). In the early Republic Jeffersonians were, in the aggregate, nearly equally likely, or rather unlikely, to support continued black political rights as Federalists: 40% of votes cast by Jeffersonians, and 45% of those cast by Federalists, were in support of black suffrage between 1785 and 1821.

Historical claims about the partisan direction of support are more grounded in later periods: between 1830 and 1860, only 12% of Democrats who voted on the issue would take a position in support of black suffrage, against 45% of Whigs, 57% of Republicans, and 84% of third-party legislators. This partisan divide emerged not during the Jackson presidency, when depending on the state the two parties could be relatively balanced on this issue; it instead emerged during the administrations that followed.

Positions on black suffrage in the early Republic also did not map clearly onto an estimated dimension of ideology. The right panel of figure 3 shows the estimated location of the median supporter and opponent of black suffrage on the first dimension of political conflict, based on a quantile regression of party affiliation interacted with successive five-year intervals. During the first several decades of the Republic there was no consistent pattern, and only by the 1820s—in New York State in particular—were the estimated medians distinguishable from each other. In the 1830s and 1840s support for black suffrage became more closely associated with legislators on the right side of the ideological dimension—largely Whigs—while opposition became associated with the left.Footnote 11 These patterns contradict characterizations from the historical literature and indicate that the issue’s relationship to party and ideology changed significantly across the early Republic and antebellum eras.

Legislative Positions on Black Suffrage

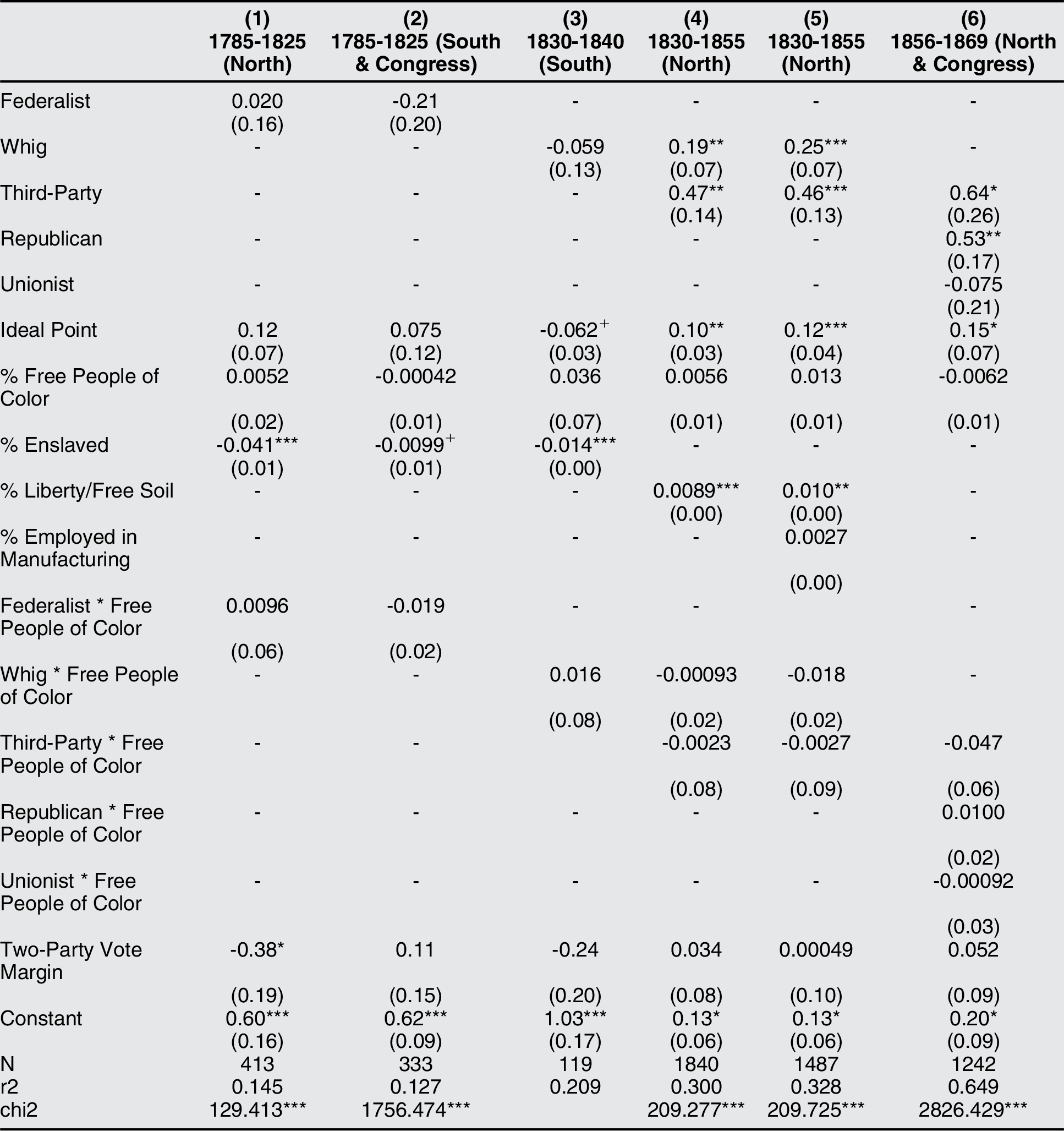

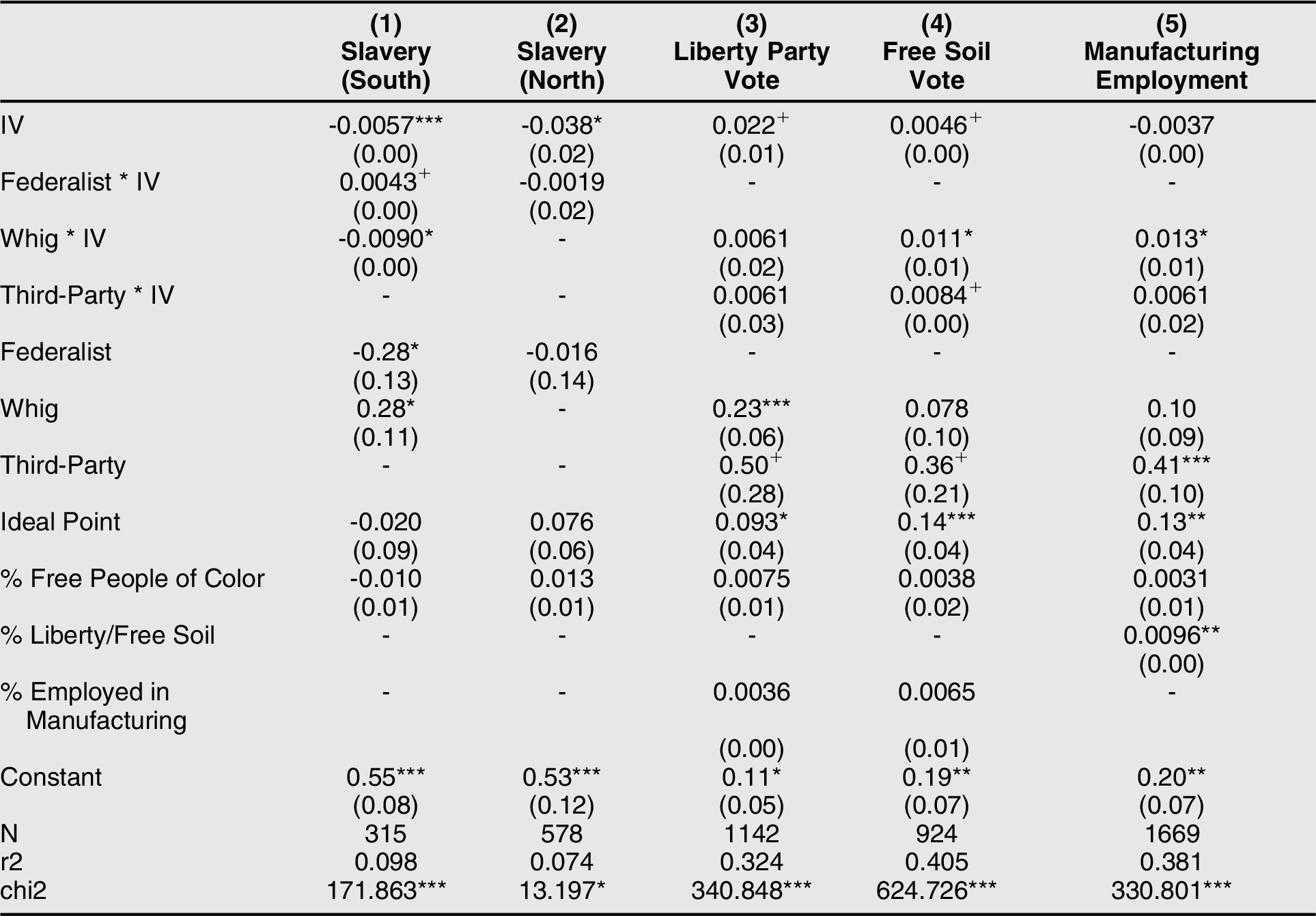

Understanding why positions became sorted by party requires that we identify the types of districts and political factors associated with voting for black suffrage. Before turning to the historical discussion that follows, I provide an initial descriptive account of some of the statistical correlates of legislative voting. I estimate a series of linear probability models with vote-specific fixed effects, divided into the first, second, and third party systems.Footnote 12 In each case the dependent variable is whether a legislator voted in favor of black suffrage. The main demographic variables are the free black community as a proportion of the district total; and for available years the proportion held in slavery and the proportion employed in manufacturing. The main political variables are the party affiliation of the legislator as well as several measures of the district’s politics, including district competitiveness—the two-party vote margin for the most recent presidential election—and the proportion of votes received by the Liberty Party in 1844 and the Free-Soil Party in 1848. Because the Democrats stood to lose most from free black voters, while Federalists, Whigs, and Republicans stood to gain, I include an interaction term for party and the free black population.Footnote 13

The results are reported in table 1. Contrary to the expectations of party-driven electoral accounts, the size of the free black community is not a significant predictor of legislator positions during any period. The effect size for the two-party vote margin is neither statistically nor substantively significant, suggesting that legislators’ vulnerability was not related to their positions on this issue. Party affiliation is not substantively important in the early Republic, but becomes so during the second and third systems; ideology, separate from party, likewise becomes significant in this period.

Table 1 Predictors of support for black suffrage

Standard errors in parentheses State-Year FE in all but (3) where only two states were included; a state-dummy (not shown) was included.

+p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

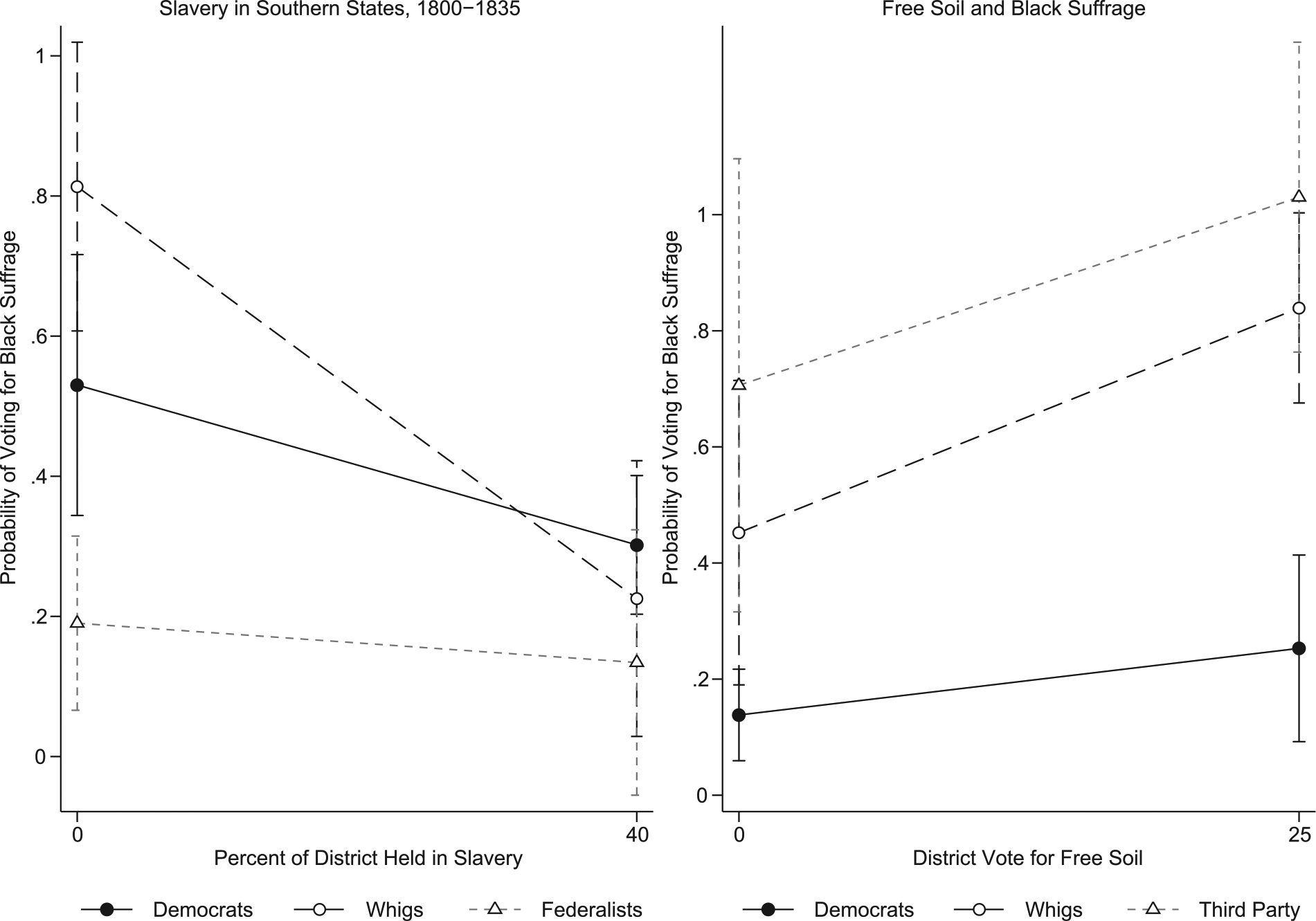

The proportion held in slavery is a significant negative correlate of positions on black suffrage in almost all models where it is included, for both southern and northern states. Similarly, district-level votes for the Liberty or Free-Soil Party are a consistently important positive correlate. To gauge the substantive significance of these variables, I estimated additional models interacting party affiliation with the proportion held in slavery, the Liberty Party/Free-Soil vote, and the percent employed in manufacturing. The results of this are shown in table 2, with the first table row indicating which variable listed in the table columns was interacted with party affiliation. Representatives from constituencies with large numbers of persons held in slavery, North and South, were the group that most consistently opposed black voting rights. Districts in which the Liberty or Free-Soil parties were able to organize an effective campaign were also more likely to see representatives adopt a pro-black suffrage position (figure 4).

Table 2 Predictors of support for black suffrage

Standard errors in parentheses

State-Year FE

+p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Figure 4 Marginal Effect of Slavery and Free Soil on Support for Black Suffrage

Constituency Preferences

Because there are no measures of district-level variation in racial attitudes, we cannot discern whether lawmakers were responsive to the antislavery movement, influential slaveholders, or to district preferences that might have covaried with these: the positive association with antislavery voting, for instance, could be a legislative response to third-party organizing or to a less racist public opinion in these areas that was present before the third parties.Footnote 14

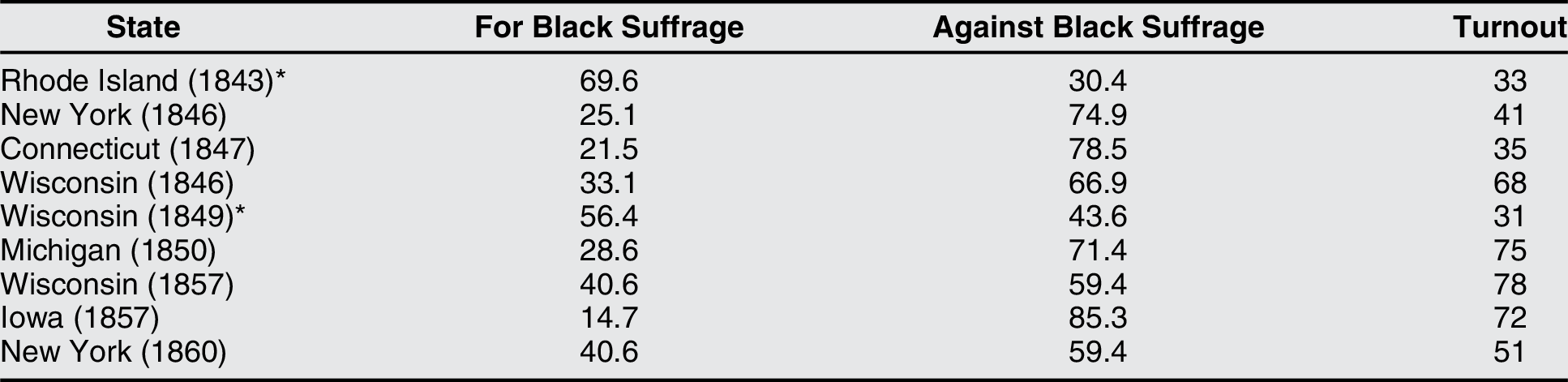

Some leverage can be gained by examining votes in black suffrage referenda. Table 3 provides the state-level proportion of votes for and against black suffrage as well as turnout as a proportion of the statewide vote for governor.

Table 3 Results in antebellum suffrage referenda (percent)

* Low turnout invalidated the results in Wisconsin in 1849; the state supreme court would later decide that the measure had passed. Opponents of the Whig Constitution in Rhode Island boycotted the votes on ratification and black suffrage, although at least 1,500 voters who supported the first voted against the second.

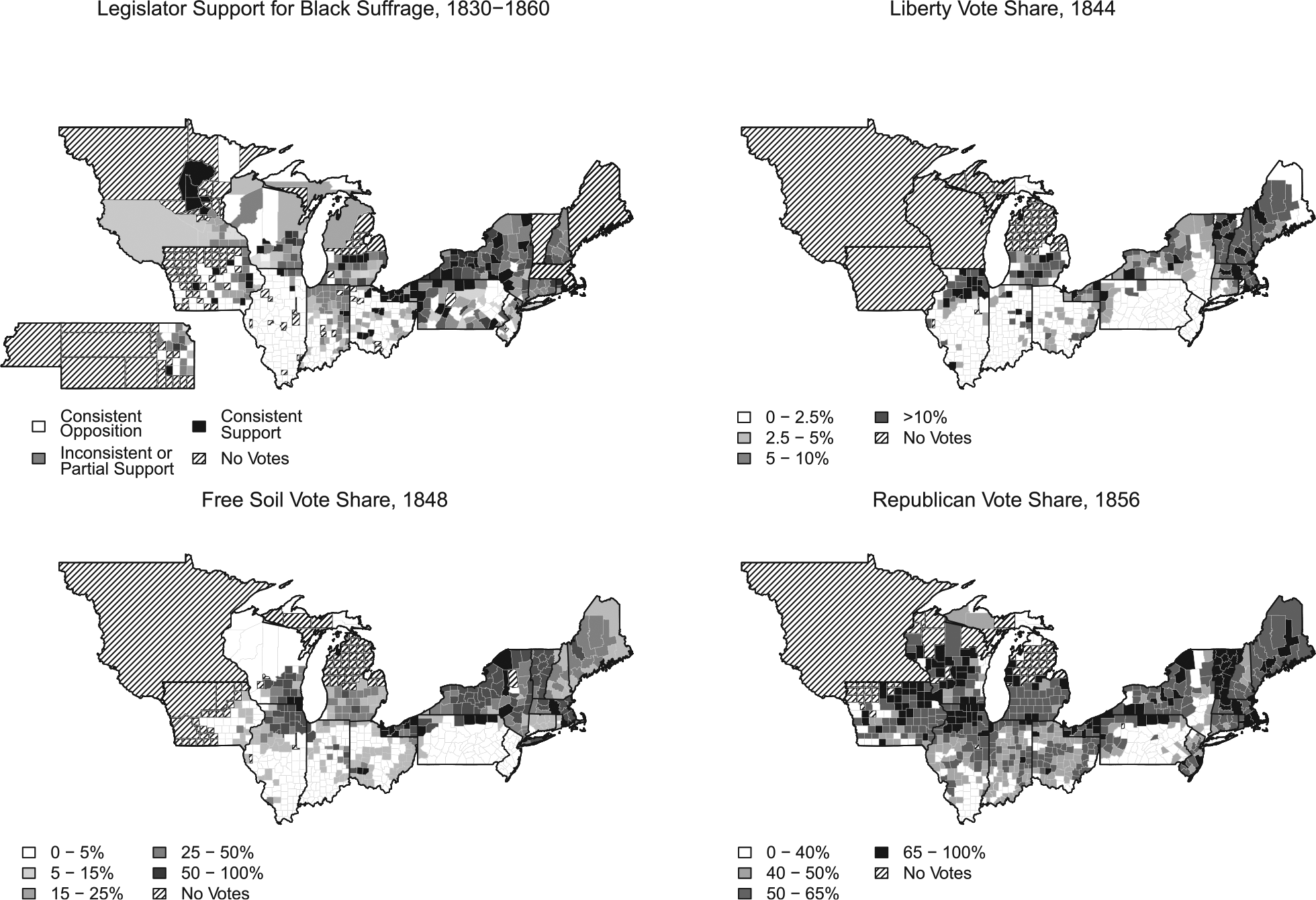

While pervasive, opposition to black suffrage was not uniformly distributed, and support was closely associated with the strength of the antislavery vote, which itself might have reflected both public attitudes as well as party organization. This can be seen in figure 5, which shows the vote distribution of the antislavery parties as well as the location of legislators who supported black suffrage after 1830, with fully shaded counties endorsing it outright and grey counties endorsing only partial measures, referenda, or divided in their support.Footnote 15

Figure 5 Geographic Distribution of Support for Black Suffrage and Antislavery Parties

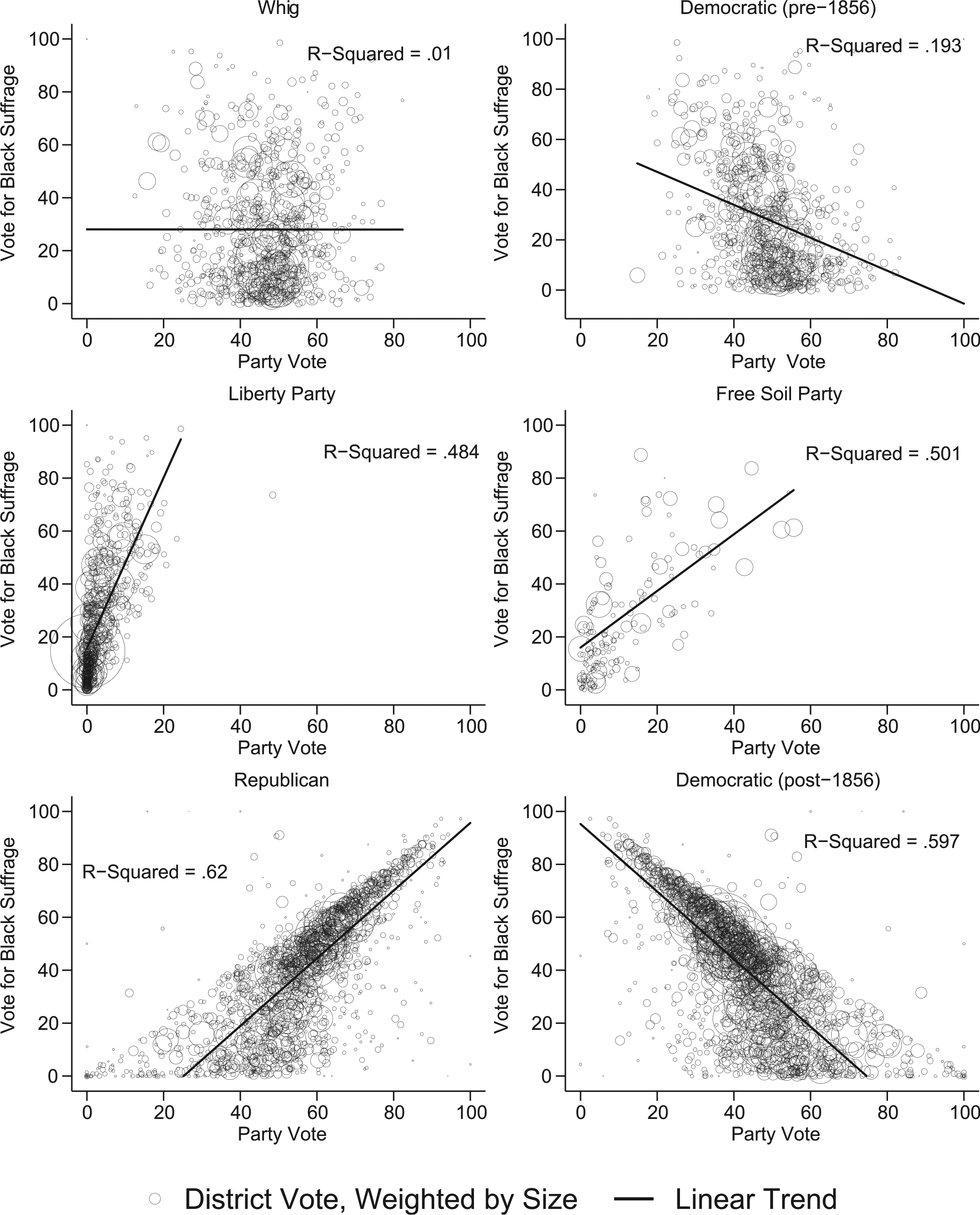

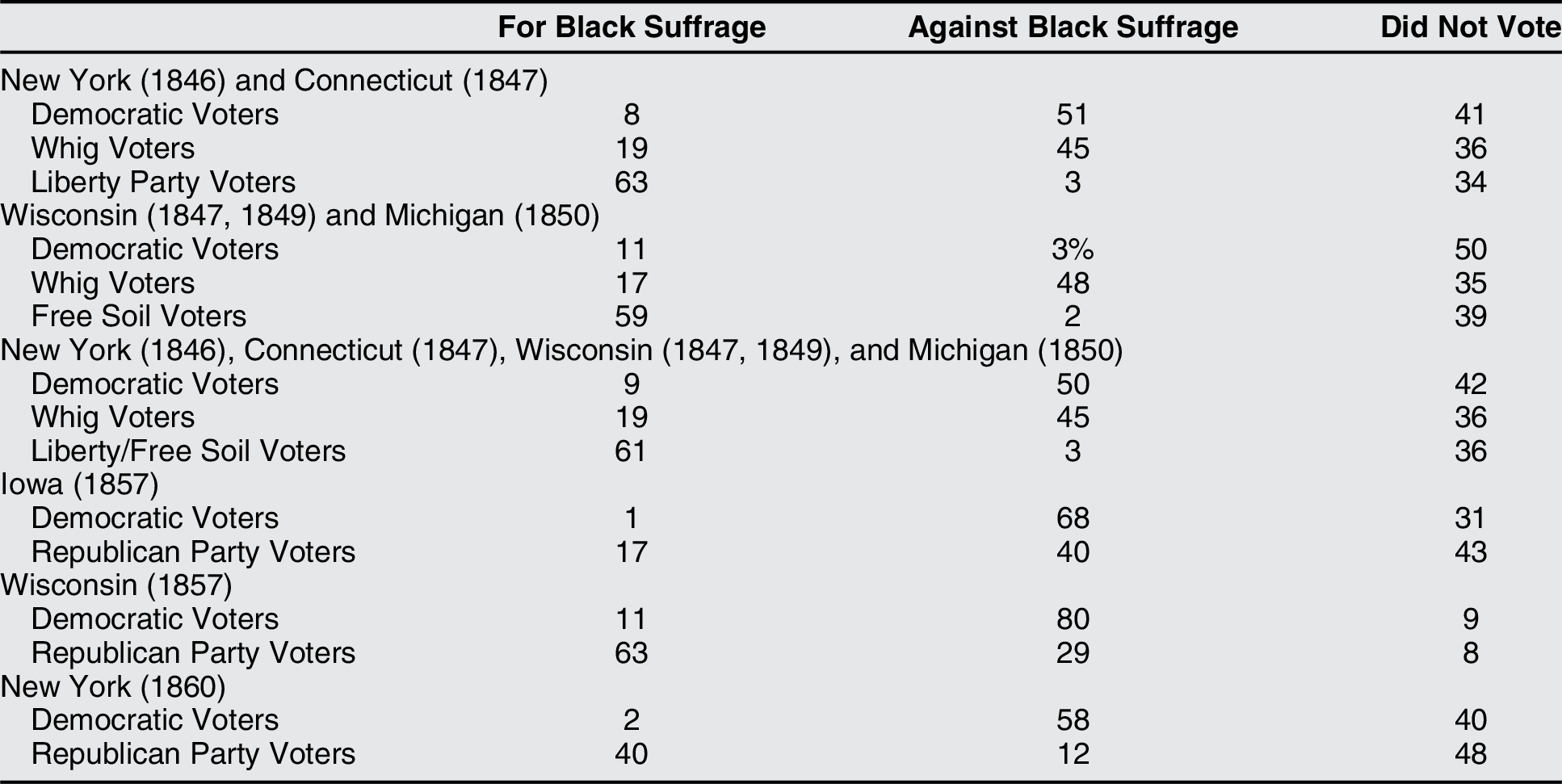

District information on voting in black suffrage referenda and in closely held presidential or state-wide elections allows us to estimate voter transition rates, the proportion of voters from different parties who voted yes or no, or abstained, on black suffrage.Footnote 16 The aggregate patterns are shown in figure 6, while table 4 reports the estimated proportion of each party’s voters who supported black suffrage in Connecticut, Michigan, Wisconsin, and New York (aggregated together), as well as later referenda in Iowa, Wisconsin, and New York. Liberty Party activists had vowed “never to vote for a constitution that placed the right of suffrage on the color of man’s skin,” and relatively few of their voters seem to have defected from this position (Waukesha American Freeman 1848). Free-Soil voters were similar, despite the fact that this party had intentionally avoided endorsing black suffrage. Supporters of the major parties were more consistently opposed: Democratic voters were especially hostile to equal rights, pluralities of Whigs voted NO, while Republicans varied significantly. All of the parties, the antislavery ones included, had a large number of abstentions.Footnote 17

Figure 6 Local Voting in Black Suffrage Referenda

Table 4 Estimated proportion of votes cast for black suffrage by party voters (percent)

Voter and average transition rates calculated using Won-ho Park (2008)

Voting for a particular party is not the same as embracing its priorities. Even in controversial black suffrage referenda there is considerable evidence that the degree to which the party organization made an affirmative decision to take (or not take) a position had a large impact on the choices made by voters: in Iowa, Republicans downplayed the suffrage issue—not printing ballots, printing ballots without direction, and in a few cases printing ballots with only the NO option (Dykstra Reference Dykstra1993)—while important factions of the New York and Wisconsin parties encouraged a YES vote. Unsurprisingly, there was much greater support among Republican constituencies in these latter states than in Iowa. Nonetheless, the aggregate patterns suggest that what public support for black suffrage existed was concentrated among antislavery constituencies; and that party strategies could shape how their supporters cast their votes, although it is less likely that this was reflected in changed racial attitudes or affect.

Legislators’ Interpretation of Black Suffrage

This descriptive overview provides evidence that legislators were concerned with local public opinion as well as nonparty interests and social movements in casting their vote, and suggests that sorting on the issue was driven by the differential impact and response to the antislavery movement. These patterns are at a high level of abstraction, and a better sense of the different motivations for legislators’ positions can be gained by studying how the issue was placed on the agenda and the rationales provided by legislators.

Black Suffrage in the Early Republic

Calculations about the partisan implications of black voting were not an important factor in the early Republic, largely because parties were relatively undeveloped. Instead, opposition to black voting seems to have been rooted in a broadly shared antipathy toward African Americans, buttressed in slaveholding communities by arguments that free black citizenship would destabilize slavery. As one representative explained his vote to disenfranchise free black Marylanders, republican principles might require that the civil rights of free blacks be protected but “self-preservation itself, compels us to … stop here.” He then recounted a commonly repeated history of Haiti in which the political enfranchisement of free black men had sparked the insurrection (The Republican Star 1803).

Elsewhere too the preferences of slaveholders were invoked: in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania opponents of recognizing black voting rights argued that doing so would “greatly offend and alarm the southern States” (The Independent Chronicle 1779, 1), while in New York, New Jersey, Maryland, and in Congress it was legislators from slave-owning constituencies who were most insistent on black disenfranchisement. In New York “the delegates most unfriendly to the Negroes were large slaveowners, while those most favorable held none … , the wealthiest men proved least sympathetic, and the poorest, most so” (Main Reference Main1973, 142).

A partisan dimension to the issue first appeared in Ohio in 1802. Here, however, the issue primarily divided along regional lines, with delegates representing the Virginia Military District (VMD)—land set aside for revolutionary veterans from Virginia—near-unanimously opposed to black rights, even as Jeffersonian committees from elsewhere “recommended that voters elect delegates who were willing to grant suffrage to every male inhabitant of Ohio, including blacks” (Thurston Reference Thorpe1972, 24; Middleton Reference Middleton2005, 28-29). While Federalists and non-VMD Jeffersonians generally supported black suffrage, all but three of the southern-born VMD delegates voted against a blanket disenfranchisement, which passed only once the “Virginia faction” leadership cajoled them into reversing their stance. The leadership later wrote that these legislators had “lost much credit” with their southern-born constituents due to their “negro votes.”Footnote 18

New York presents the strongest case for an electorally motivated disenfranchisement (Polgar Reference Piven, Minnite and Groarke2011). And yet pro-disenfranchisement Jeffersonians here had difficulty persuading their co-partisans of its expedience: when a draft suffrage clause in the 1821 constitutional convention included the word “white,” a majority of Federalists, the Clintonian faction of the Jeffersonians, and a large minority of the dominant Bucktail/Tammany Hall faction voted to strike it out. Despite the Bucktails having a sizeable majority in the convention, disenfranchisement failed on its first consideration. Opponents explicitly framed disenfranchisement as a corollary of slavery, arguing that it contravened the position the state had taken during the recent Missouri crises. Federalist Peter Jay reminded delegates that the state legislature had then “taken high ground against slavery, and all its degrading consequences and accompaniments,” i.e., the racial distinctions that denied free black Americans’ citizenship (Carter and Stone Reference Carter and Stone1821, 184).

Other delegates were more concerned with how it would be perceived by white constituents, recently active abolitionist organizations, and the southern slaveholders who occupied positions of influence within the national party (McManus 1966, 185). Contemporaries suggested that legislators voted to strike the word “white” out of a worry that it would arouse the opposition of the abolition organizations (New York Columbian 1821; Cole Reference Cole1984, 59, 69). Bucktail leader Martin Van Buren’s vote against disenfranchisement was justified on the grounds that “but a year before that the State had been agitated by the Missouri question, and advocates of negro equality were not wanting” (Extra Globe 1839, 86), while the Bucktail press framed black suffrage as a threat to national unity, “a very dangerous [question] in this country, where a large portion of the union held slaves” (National Advocate 1821a, 1821b).

Bucktail leaders tried to persuade their members by highlighting how black voters in New York City supported their Federalist rivals (National Advocate 1821b; Carter and Stone Reference Carter and Stone1821, 186) and by arguing that worries of an antislavery backlash against a disenfranchising constitution were overstated given white racism (Carter and Stone Reference Carter and Stone1821, 288). An eventual compromise that left only wealthy black men enfranchised, however, ultimately gained as many Clintonian and Federalist converts as Bucktails, winning a majority of both Jeffersonian factions and a large minority of Federalists. Partisan calculations likely explain the efforts of the Bucktail leadership; but they do not explain why so many Bucktails voted against disenfranchisement, nor why so many of their partisan and factional rivals voted for it.

Polarization in the Antebellum Era

The inclusion of an equal suffrage for men among the priorities of the radical antislavery movement that emerged in the 1830s was a response to the demands of free black activists, who argued that the “real battle ground between liberty and slavery is prejudice against color” (Sinha Reference Siczewicz and Long2016, 306, 308, 325; Stewart Reference Stanley1997, 110; Field Reference Field1982, 59; Quarles Reference Quaife1969; Levesque Reference Levesque1970; Wesley 1941). “Echoing the Liberty position,” advocated most insistently by free black Americans, Wisconsin abolitionist Rufus King “insisted that slavery and racial prejudice stemmed from the same misguided beliefs” and that black suffrage would be the first step toward emancipation (McManus Reference McManus1998, 23; Waukesha American Freeman 1848). The Detroit Colored Vigilant Committee’s “moral and political warfare” for equal rights was joined by the newly-organized Liberty Party, which denounced disenfranchisement as “cringing to slavery” and mobilized “hundreds of white voters over the entire state” in a petition campaign (Formisano Reference Formisano1972, 24-26). Free black Americans played a critical role in antislavery activism, fostering an organizational interest and programmatic commitment in supporting an expansion of the electorate. The emphasis given by the antislavery movement to black rights helped foster a class of enfranchised whites who were supportive of black suffrage, while black activism indicated to ambitious legislators in districts with a sizeable free constituency that they could be mobilized in future elections, two mechanisms important for democratizing reforms (McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2015; Teele Reference Stewart2018a).

The initial response to antislavery, however, was a backlash by both major parties. Whigs used Van Buren’s earlier vote to oppose disenfranchisement in New York as a campaign issue against him in 1836, claiming that “upon this question of paramount importance to the South” he had revealed a “disposition” that was “totally irreconcilable with our views of policy or safety.” “We cannot so far forget our own social interests,” argued one Whig, “as to sanction the civil elevation of a class of men, who must always be to us dangerous political allies.” Democrats responded by insisting that “a majority of Van Buren’s political friends” had come to recognize that free blacks were “unsafe repositories of the right of suffrage” (Bateman Reference Bateman2018, 172; National Banner and Nashville Whig 1835; Shade Reference Schlozman1998, 466-68, 470).

Leaders of all major parties in the 1837–1838 Pennsylvania constitutional convention urged their members not to propose disenfranchising free black men lest it attract the opposition of the abolitionists (Agg Reference Agg1837 v.2, 357, 472-84, 549, 561). Rather than seeing an electoral opportunity, party leaders worried about backlashes from both racist white constituents and the antislavery movement (Agg Reference Agg1837 v.3, 86-89; Wood Reference Wesley2011, 96). When one member insisted, against party urging, on a vote to add the word “white,” his proposal was defeated by a bipartisan majority. The vote quickly gained exposure in the national press, and state Democratic leaders, in consultation with John Calhoun, Roger Taney, and Senator James Buchanan, now organized an extensive petition campaign against “racial amalgamation” (Wood Reference Wesley2011, 86-87). When the issue was revisited a few months later, both Whigs and Democrats urged support for disenfranchisement by invoking national unity, asking whether “they wish to tear down our glorious stars and stripes” or place “the right of the negroes to vote… in the scale against the union of these states” (Agg Reference Agg1837 v.3, 684-96; 1838 v.9, 353, 393; Wood Reference Wesley2011). The petitions convinced many delegates that “opposition to negro suffrage, was almost unanimous” and there could be “no mistaking public opinion on this subject” (Agg Reference Agg1838 v.9, 357, 380), although numerous petitions arrived on both sides (Bateman Reference Bateman2018, 191). Seventeen members, from all parties, switched their votes to support disenfranchisement.

The themes of national unity and public racism were raised in almost every legislature or convention where black suffrage was debated, by politicians who argued that it “would be dangerous … to the union of the States” (Croswell and Sutton Reference Croswell and Sutton1846, 1047) and by party leaders who warned that it would send a message to the South that they were “favorably disposed to the abolition movement” (McManus Reference McManus1998, 21). Antislavery legislators in turn framed racial exclusions as contrary to the country’s republican purposes and as complicity in slavery, basing their support for equal rights on their opposition to “the institution of slavery in this country” and their eagerness to “vote against it in any manner or shape” (Quaife Reference Polgar1919, 217).

After Van Buren won the presidency in 1836 with reduced southern support, Democratic organizations across the country committed themselves to anti-abolitionism (Russo Reference Rothbauer1972,18, 22; McFaul Reference McFaul1975, 32). Future Liberty Party vice-presidential candidate Thomas Earle was kicked out of the party for his defense of black suffrage, and abolitionists noted that similar experiences had been meted out to others “in less conspicuous stations” (Emancipator and Free Republican 1843, 196). A bipartisan Wisconsin coalition pledged to “universal suffrage without invidious distinctions” foundered when the Democrats were “warned they would be drummed out of the party” (McManus Reference McManus1998, 25). An influential New York leader announced that “we’ll purge the Democratic party of the fanaticism which has been creeping into it for years, by separating the Negro suffrage fanatics from it, and drive them into the Federal [Whig] ranks where they belong … [We] will not fraternize with any men … who are in favor of Negro Suffrage” (New-York Tribune 1846a). Southern newspapers aligned with the Polk administration urged a New York convention to disenfranchise all free black men (Barre Patriot 1846), and when the chair of the drafting committee proposed doing so he was given a lucrative patronage office (New-York Tribune 1846b). Politicians across the country were being made “aware of the larger implications of black suffrage” (Wood Reference Wesley2011, 87), with contemporaries blaming Democrats’ need to “please the South and keep good their party” (Emancipator and Free Republican 1843).

The pressure on Democrats contributed to the sorting seen in figure 3. Former Democrat Benjamin Gass broke off all ties with a party that denied that “all mankind are created free and equal,” becoming a Liberty Party activist (Daily Ohio Statesman 1842). A Michigan Democrat urged his party to endorse black suffrage; he would soon be denounced as a “traitor to the democratic party” (Michigan Reference Michigan1845; Detroit Free Press 1855). An Ohio gubernatorial candidate who had called for the repeal of the state’s “black laws” was admonished when this came to light; he now “categorically denied any interest in ‘Negro equality’” (Middleton Reference Middleton2005, 135, 139).

The other component of the polarization was the growing willingness of Whigs to support black suffrage. The organization of the Liberty Party in 1840 was especially threatening to the Whigs, posing a credible threat of exit of the type that McConnaughy emphasizes as essential for programmatic enfranchisement (2015). As one Wisconsin legislator noted, “they had among them what was called a liberty party, and universal suffrage was their one idea. Among the resolutions passed by the Whig convention of that county one year ago last fall, was one instructing their delegates to go for universal suffrage” (Wisconsin 1848, 130).

Abolitionist campaigns also sought to expand public support for black suffrage, their lectures explaining how racial distinctions in law were essential to slavery’s operation and their petitions urging legislators to indicate their opposition to slavery by abolishing such distinctions. It was “the untiring efforts of the abolitionists out of doors” that placed black re-enfranchisement on the political agenda in Connecticut (The Liberator 1838, 1), and petitions for black suffrage flooded legislatures across the country. “From the early forties,” writes one historian of black suffrage, “antislavery men had been so persistently advocating equality, citizenship, and education for negroes that they liberalized sentiment toward them” in regions of high antislavery activity (Olbrich 1912, 89). The efforts of black Ohioans such as John Malvin and John Mercer Langston—who in 1855 would be elected town clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio—put black suffrage and civil rights on the state’s agenda; when antislavery forces gained the balance of power in the legislature, they forced a repeal of most of the “black laws” and elected an advocate of black suffrage—Salmon Chase—to the U.S. Senate. After the War, Chase would again emerge as one of the most important Republican champions of enfranchisement (Cheek Reference Cheek1996; Middleton Reference Middleton2005, 145-55).

Very few Whig leaders, however, endorsed black suffrage, and those who did gave only hesitant support. One, for instance, “announced” his position in a letter that supporters were authorized to show only in private (Daily Free Press 1850c). Party leaders were anxious to retain voters subjected to intense antislavery campaigns while not offending a larger white public; the individual legislators and factional leaders who pressed the issue, by contrast, did so despite having “a perfect consciousness that we incurred general obloquy and injured our political associates” (Field Reference Field1982, 80; Stanley Reference Smith1969).

Some tried to navigate this dilemma by delegating the decision to voters. During New York’s constitutional convention of 1846, “both parties seemed troubled by their lack of unity on black suffrage” and agreed to a referendum in order to relieve “themselves of final responsibility for its fate” (Field Reference Field1982, 57). In Connecticut, a rare bipartisan majority voted to send black suffrage to the people. “If for no other reason,” writes Lex Renda, “Whigs and Democrats wanted the issue depoliticized so that the Liberty party could not profit from it. Allowing voters to defeat black suffrage accomplished this goal nicely” (2002, 249).

One delegate explained that while he supported a referendum, he wanted it known “that I should vote against this proposition at the polls if it were submitted twenty times.” Another begged “to be distinctly understood, that I am not in favor of negro suffrage myself, but I am willing to leave the question open to the people.” Schuyler Colfax, later a Republican Vice-President elected on a platform endorsing black voting rights, explained in 1850 that “although I shall vote against adopting a Constitutional provision extending the right of suffrage to negroes, as I told the people of my district before they sent me here, a constituency as deeply imbued with free soil sentiments as the constituency of any other delegate on this floor, I shall cheerfully vote for [the] reception” of petitions to do so. Others hoped that a defeat in a referendum would “would stop [antislavery] agitation,” but were warned that abolitionists “would not be satisfied.” Equal rights was only a stepping stone to their real purpose: “their object is not here, but to abolish slavery in the South” (Michigan Reference Michigan1850, 297; Quaife Reference Polgar1919, 228, 543; Fowler 1851, 78, 231, 253).

The defeats provided definitive proof of the racism of white public opinion, prompting James McCune Smith to reflect that the electorate harbored “a hate deeper than I had imagined” (Stewart Reference Stanley1997, 112).

Republican Equivocations

The formation of the Republican Party did not change the party calculus that there were more racist whites to offend than free black men to win. For the first time, however, the antislavery movement was affiliated with a national party, with Liberty Party, Free-Soilers, and “conscience Whigs” constituting important parts of its membership. Republican legislators regularly took public positions in favor of black suffrage and helped disseminate an ideological argument tying civil and political rights for black Americans to the antislavery cause: opposition to slavery and support for black suffrage were, according to many Republican legislators, manifestations of the same effort “to strike down … tyranny, and the idea that I am better than thou” (King, Freeman, and Larimer 1920, 300). Tying equal rights to a broader antislavery position and to what they insisted were the country’s republican commitments was an effective continuation of the rhetorical strategy advanced by political antislavery and the Liberty Party.

The pro-suffrage effort intensified after 1850: proposals were introduced in New York every year before the Civil War and passed the House on three separate occasions, while in Connecticut a pattern emerged in which a majority of Know-Nothings and Republicans would vote to strike the word “white” in one session only for the leadership to keep it off the agenda in the constitutionally-required second session, signalling support for an antislavery priority without provoking the racist white majority (Field Reference Field1982, 80-81; Renda Reference Quarles2002). A Republican committee in Michigan recommended the abolition of all racial distinctions, but the Senate refused to act, aware that a vote would put a large number of Republicans on the record for a measure that could not pass the House. When residents of Cass County, Michigan, established a racially equal franchise for school board elections, Republican legislators were near-unanimous in their refusal to overturn it (Formisano Reference Formisano1972). When the Ohio Supreme Court in 1859 expanded the definition of “white” to include persons with more than half-European ancestry, only 7 (13%) Republicans joined all Democrats in voting for what Democrats called “a Union-saving law” to overturn the Court’s decision (Sandusky Register 1859). By 1860 nearly 60% of Republicans who had cast a vote on black suffrage had done so in favor, although proposals to do so were more frequent where the issue was popular among Republicans.

The party’s leadership as well as important factions within the party opposed black suffrage on the grounds that it would repulse potential white voters. One Iowa Republican was pleased that on the question of slavery and civil rights “the Republican party are reformers, and are, seeking to … enlighten public opinion.” But advocates of black suffrage were asking the party to “do that, which when done will turn against us, I may say, at least, one half of the Republican party” (Lord Reference Lord and Blair1857, 676). A member of Congress was criticized by a Republican newspaper for his effort to secure black voting rights in the District of Columbia: pro-suffrage members had “one eye on the Speaker and one on their districts at home,” but were going to threaten the party’s viability elsewhere (Daily Chronicle 1856, 3). As many contemporaries noted, the “Republican organization may rebel against” the demand for black suffrage in order to win the support of the white electorate; “but if they do they [will be] … doomed and damned” by antislavery activists (Daily Ohio Statesman 1857). It was the efforts of these activists that ensured that sooner or later “the Republican party must adopt negro voting as the leading article in its creed or else fall to pieces. The petitions which are presented to the Legislature in favor of this measure, are in number frequent, and imperative in tone” (Daily Ohio Statesman 1856).

The Republicans at the Leavenworth convention in Kansas refused to include the word “white” in their draft constitution, but they allowed the legislature to revisit the issue. One Republican calmed a friend outraged by this concession by noting that “we shall be carful [sic] to elict [sic] a judiciary that will declare any Law passed by any future Legislature restricting the right of colored men, unconstitutional, and consequently null and void, you may depend on that.” A handful of Republicans, however, explained that they signed the constitution “under protest for the reason that we believe a majority of our constituents are opposed to negro suffrage.”Footnote 19 While the constitution was popularly ratified, its egalitarianism led to its defeat in Congress. In a subsequent convention only a handful of Republicans voted to strike “white,” and a delegate remarked that most “don’t wish to face the music and take the responsibility of the record” (King, Freeman, and Larimer 1920, 193). Democrats across the country delighted in Republican divisions, believing that any public support for black suffrage would discredit the new party for “all except the most miserable fanaticks for whom there [is] no hope” (Dykstra Reference Dykstra1993, 151).

In Minnesota, a caucus decision to endorse black suffrage collapsed after some members changed their position. A Republican explained to his furious colleagues why he had done so:

I have come to the much abused doctrine of expediency … . Our action here will be taken as the action of a party; … we should study the interest of that party … . [T]he only policy on which we can sustain ourselves before the people—at least in my section of the county—[is] to put the word “white” into the Constitution, and let the people vote it out if they will. And I pledge myself in this Convention, when our Constitution comes before the people, to use my utmost endeavors to have them vote it out (Andrews Reference Andrews1858, 394-95).

A large pro-suffrage bloc continued to force the issue in the convention, insisting that equal rights be made a core principle of the state party. “‘Negro Suffrage’ is not a plank in the National Republican Platform,” conceded one. “But does it follow that what would be an impracticable plank in a national platform of party principles, is an impracticable plank in a State platform of a party” (Andrews Reference Andrews1858, 541). The federated character of the parties provided a mechanism for positions to become associated with the parties regardless of national strategies (Schickler Reference Schattschneider2016).

Many northern Republicans saw black suffrage as “political suicide” (Wang Reference Valelly, Valelly, Mettler and Lieberman1997, 6), even as large numbers continued to advocate for it. In pushing the issue, they helped define the ideological content of what would eventually become “Radical Republicanism,” which at its core was the antislavery argument that the fight against slavery must confront the legal infrastructure of white supremacy. This argument, honed by decades of organizing, would after the War be joined to an insistence that affirming equal citizenship was necessary to prevent the return of the “slave power” and the overthrow of the republican regime. Radical Republicans, in short, could then argue that what many of them had long been fighting for—to “re-establish the government upon the distinct enunciation of the doctrine that ‘all men are created equal’”—was now aligned with the party’s electoral interest, a providential convergence of expedience and principle. As George Boutwell insisted, in a speech famous for coupling partisan and principled programmatic arguments for enfranchisement, “you have but one path before you, and, thank God, it is the path of justice, and in it you must walk” (Boutwell Reference Boutwell1865, 5,9, 33).

Conclusion

The long history of contestation over black citizenship was a fight not just over political power, but over the definition of American peoplehood and the terms of national citizenship.

The most important factors working against lawmakers’ recognition of black citizenship were the need to maintain a national coalition with slaveholders and the need to win support among racist white constituents. Even after the Republicans jettisoned the first, they were still constrained by the second. The major force pushing for black political rights, however, was not a top-down party calculus—important as this would become after the War when the issue was enfranchising freed black American men in the South. It was instead the insistent demands of the antislavery movement, who at the urging of its free black activists advanced a broad program against white prejudice, putting black suffrage back on the political agenda and persuading a growing number of legislators that it was worth supporting.

This has implications for our understanding of American history, the contemporary politics of voting rights, and the long legacy of white supremacy. As a historical matter, it suggests a reinterpretation of American democratization. As Richard Valelly has noted, the nineteenth-century United States presents a seeming exception to the comparative pattern that the male franchise was won through threat of revolution and not top-down partisan machinations (Valelly Reference Valelly2016, 452). But organizing for revolution is not the only means by which the disenfranchised can pursue their inclusion. While an electoral threat was a necessary condition for the Republican Party leadership to finally embrace black suffrage (Valelly Reference Thurston2004), the task of rallying several hundred legislators behind an unpopular position was facilitated by the decades of organizing that had led to its being embraced by a large portion of the party, who had articulated their support of this cause in terms of a powerful ideological message joining antislavery, national purpose, and republican principles. It is almost inconceivable that mass emancipation or mass enfranchisement would have happened absent the Civil War. But it was antislavery activism that broke open the bipartisan national consensus against black citizenship and set the stage for Reconstruction, when a party that had been debating black suffrage since its inception, many of whose partisans had endorsed it before the War, was faced with an electoral threat and a solution that had a deep constituency and long lineage within the party.

This argument has contemporary implications, as new efforts at voter suppression and counter-movements gain traction. It underscores that while party calculations about strategic advantage can be important in expanding or limiting access to the ballot, reforms can also be advanced by nonparty groups with their own motivations and concerns (see, for example, Mayer Reference Mayer2012). And they provide further evidence that the expansion of political rights, in particular, requires politicians to be persuaded that their support will be rewarded, a task that will often fall on social movements rather than party leaders (McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2015; Piven, Minnite, Groarke Reference Park2009).

We are today again witnessing a pattern of polarization in which the boundaries of American national identity have become a defining cleavage separating the parties. The antebellum American regime, built around the slavery and suppression of black citizenship, was sufficiently robust to withstand intense partisanship. It could not, however, withstand a form of polarization in which these had become the major issues separating the parties. It remains an open question how well the contemporary American regime will manage the stress caused by a polarization in which questions of racial civic and political standing are once again central to the partisan divide. Perhaps more important, however, is whether the consequence will be to empower inclusionary and egalitarian political projects or their opposite.