Introduction

Spirituality remains an increasingly distinct subject of reflection within various disciplines, including palliative care. Although there is widespread recognition that the spiritual dimension should be incorporated into palliative care (Vilalta et al., Reference Vilalta, Valls and Porta2014; Gijsberts et al., Reference Gijsberts, Liefbroer and Otten2019; Best et al., Reference Best, Leget and Goodhead2020), little is known about how spirituality is experienced by these patients’ informal caregivers. In the following, we use the term “family caregiver” (FC) to refer to those persons providing care as either relatives of the patient or other closely related persons, such as friends.

Defining “spirituality”

Spirituality itself is a multidimensional complex concept. The findings, thus, indicate heterogeneous or entirely missing definitions of spirituality in research projects (Wright, Reference Wright2001; Gijsberts et al., Reference Gijsberts, Liefbroer and Otten2019), which reveals a poor understanding of spiritual experiences and needs among FCs in the field of palliative care. As per the consensus definition (Puchalski et al., Reference Puchalski, Ferrell and Virani2009, Reference Puchalski, Vitillo and Hull2014), adopted by the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), “Spirituality is the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant and/or the sacred” (Best et al., Reference Best, Leget and Goodhead2020).

Spirituality among FCs in palliative care

International research on spirituality in the context of palliative care increasingly includes FCs (Mok et al., Reference Mok, Chan and Chan2003; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Wilson and Olver2011; Ross and Austin, Reference Ross and Austin2015; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Neufeld and Harrison2016; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, Seah and Clayton2020; Özdemir et al., Reference Özdemir, Doğan and Timuçin Atayoğlu2020). However, the spiritual dimension often remains a subordinated focus of investigation, resulting in a limited understanding of the appearance and relevance of spirituality in the group of FCs (Buck and McMillan, Reference Buck and McMillan2008; Delgado-Guay et al., Reference Delgado-Guay, Hui and Parsons2011; Harrington, Reference Harrington2012; Williams and Bakitas, Reference Williams and Bakitas2012).

In previous studies, FCs rated spirituality as an important domain, which was stated more frequently than health and finances (Brandstätter et al., Reference Brandstätter, Kögler and Baumann2014). Lalani et al. (Reference Lalani, Duggleby and Olson2019) reviewed 24 studies, touching on the topic of spirituality among FCs in palliative care contexts and concluded a high correlation of spirituality and burden among FCs. One study found 58% of FCs of patients with advanced cancer to be burdened by anxiety, depression, denial, and spiritual pain (Delgado-Guay et al., Reference Delgado-Guay, Hui and Parsons2011), whereby spirituality was identified as a positive influential aspect for functional coping strategies. Another study found spirituality to be used in resolving ethical dilemmas in the daily caregiving experience of female FCs (Koenig, Reference Koenig2005). Accordingly, authors found spirituality as a coping strategy used by FCs of patients undergoing palliative care (Paiva et al., Reference Paiva, Carvalho and Lucchetti2015; Selman et al., Reference Selman, Brighton and Sinclair2018; Özdemir et al., Reference Özdemir, Doğan and Timuçin Atayoğlu2020). Despite those findings, spirituality remains an oftentimes overlooked domain in supporting FCs, as shown by Sloss et al. (Reference Sloss, Lawson and Burge2012), who quantified spirituality as a topic of discussion between healthcare professionals and informal caregivers of patients during the end of life at only 27%, while over 80% of those caregivers indicated the wish for a wider range of support regarding spirituality. Studies imply that healthcare professionals should include spirituality in offers of support for FCs to understand their preferences (Jaul et al., Reference Jaul, Zabari and Brodsky2014), console them (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Maddalena and Njiwaji2014), and promote spiritual well-being (Sterba et al., Reference Sterba, Burris and Heiney2014; Ross and Austin, Reference Ross and Austin2015). Selman et al. (Reference Selman, Brighton and Sinclair2018) found many spiritual concerns among FCs, while interdisciplinary spiritual care was described as lacking. Others correspondently derive the implication that healthcare professionals and researchers should internalize the importance of spirituality for FCs (Skalla et al., Reference Skalla, Smith and Li2013; Delgado-Guay et al., Reference Delgado-Guay, Chisholm and Williams2016), encouraging the spiritually engagement with FCs (Penman et al., Reference Penman, Oliver and Harrington2013).

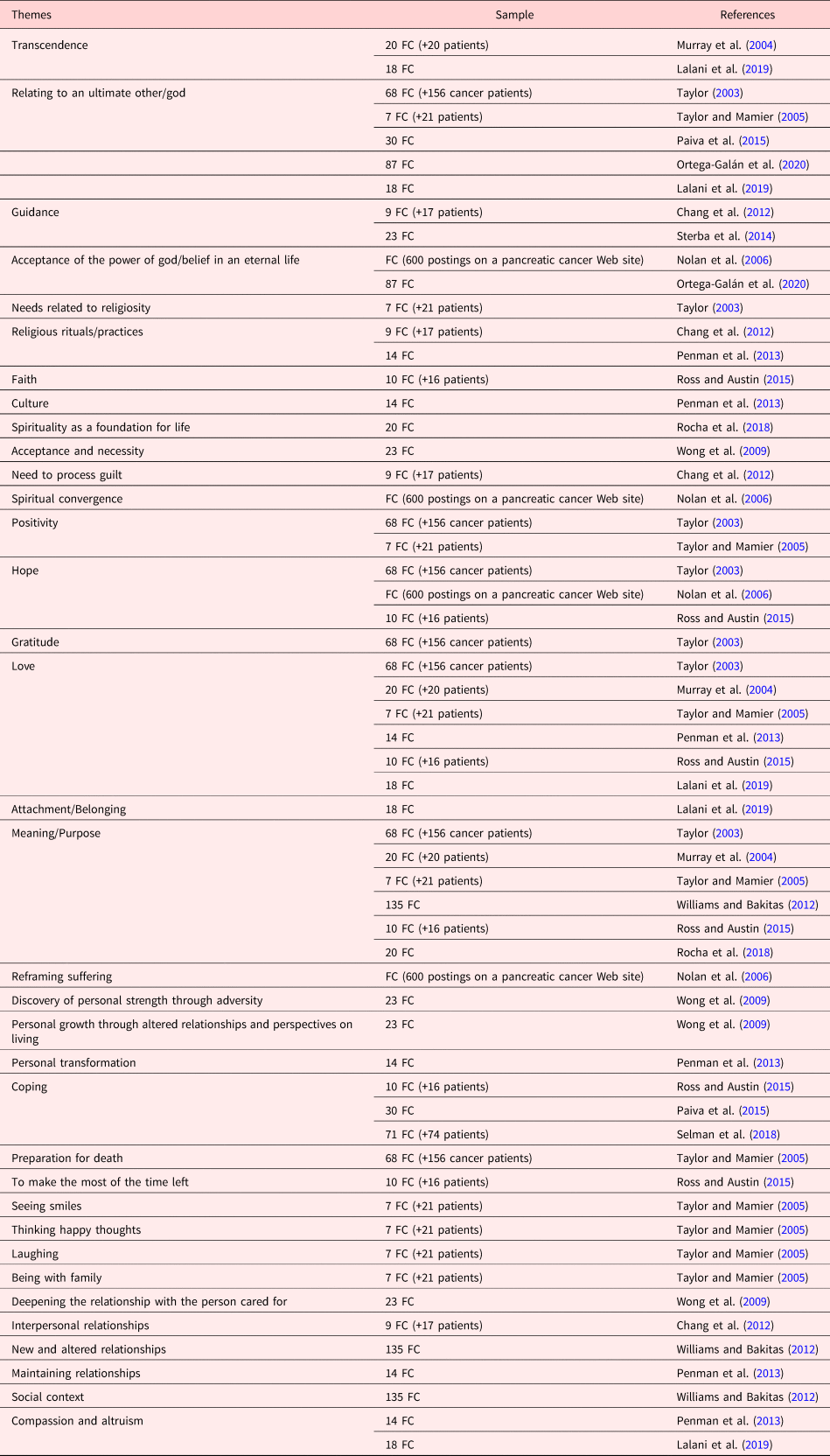

Reported themes associated with spirituality and spiritual needs of FCs in previous research included the scope of hope, transcendence, faith, religiosity, or power of god (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Kendall and Boyd2004; Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Hodgin and Olsen2006; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Stein and Trevino2012; Ross and Austin, Reference Ross and Austin2015; Bar-Sela et al., Reference Bar-Sela, Schultz and Elshamy2018); practical facets like seeing smiles, positive thoughts, and laughing (Taylor and Mamier, Reference Taylor and Mamier2005); aspects associated with relationships (Taylor and Mamier, Reference Taylor and Mamier2005; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Ussher and Perz2009; Williams and Bakitas, Reference Williams and Bakitas2012; Penman et al., Reference Penman, Oliver and Harrington2013) as well as coping, personal transformation, growth, strength, and reframing suffering (Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Hodgin and Olsen2006; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Ussher and Perz2009; Penman et al., Reference Penman, Oliver and Harrington2013; Paiva et al., Reference Paiva, Carvalho and Lucchetti2015). A more detailed summary of exemplary themes and study samples is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Exemplary themes associated with spirituality among FCa

a This table complements a previously published summary by Lalani et al. (Reference Lalani, Duggleby and Olson2018).

It has been shown that spirituality is a culture-bound construct based on various subjective interpretations and meanings (Mok et al., Reference Mok, Chan and Chan2003; Keller et al., Reference Keller, Klein and Swhajor-Biesemann2013; Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Maddalena and Njiwaji2014). Since existing results on spirituality among FCs and derived implications were mainly developed in other cultural contexts and care systems (see Table 1), the findings can only be transferred to a limited degree to care situations in Europe and require critical revision. Yet, European studies showed that spiritual competency is seen as indispensable in matters of caregiving and that mindfulness, as part of spirituality, can be supportive to informal caregivers (Gijsberts et al., Reference Gijsberts, Liefbroer and Otten2019).

This exploratory qualitative secondary analysis intends to contribute to the understanding of the appearance of spirituality among FCs of patients with incurable cancer. Data were analyzed to answer the question of how spirituality manifests in the experience of FCs of patients in the context of palliative care.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a secondary supra analysis (Heaton, Reference Heaton2004) of two qualitative datasets, which derived from studies on burdens and needs of primary FCs of advanced cancer patients who underwent specialist in inpatient palliative care (Ullrich et al., Reference Ullrich, Theochari and Bergelt2020).

According to Heaton (Reference Heaton2004), supra analyses transcend the focus of the primary investigation, intending to examine new research questions and generating additional knowledge. Besides the maximized use of preexisting data (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Maddalena and Njiwaji2014), qualitative secondary analysis (QSA) can contribute to the prevention of research fatigue and reduce expendable intrusion (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017) in vulnerable populations, such as FCs of terminally ill patients. Written informed consent had been provided by all participants with respect to the original research, which has also been approved by the ethics committee of the General Medical Chamber, Hamburg (PV5122).

Data material and appraisal

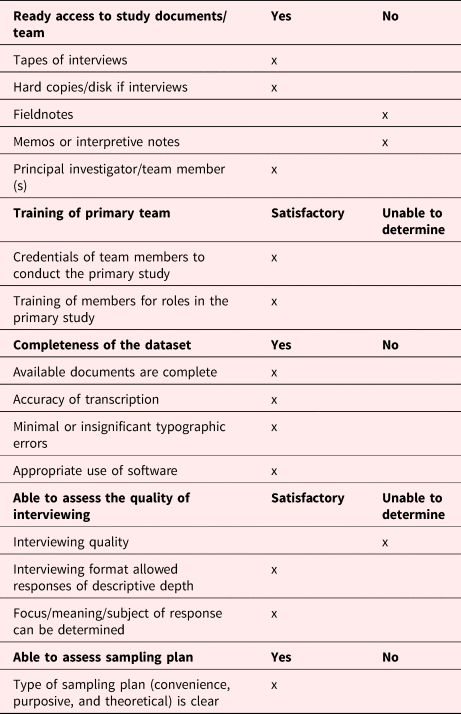

Data from the primary studies were merged as part of an amplified QSA. We evaluated the datasets to determine their feasibility for secondary purposes regarding accessibility, quality, and suitability, as per the assessment criteria suggested by Hinds et al. (Reference Hinds, Vogel and Clarke-Steffen1997). The appraisal is portrayed more detailed in Table 2. Despite some limitations, the quality of the original data was deemed sufficient, complete, and suitable for the purpose of QSA (Leget, Reference Leget2018).

Table 2. Appraisal of primary data

Setting and participants

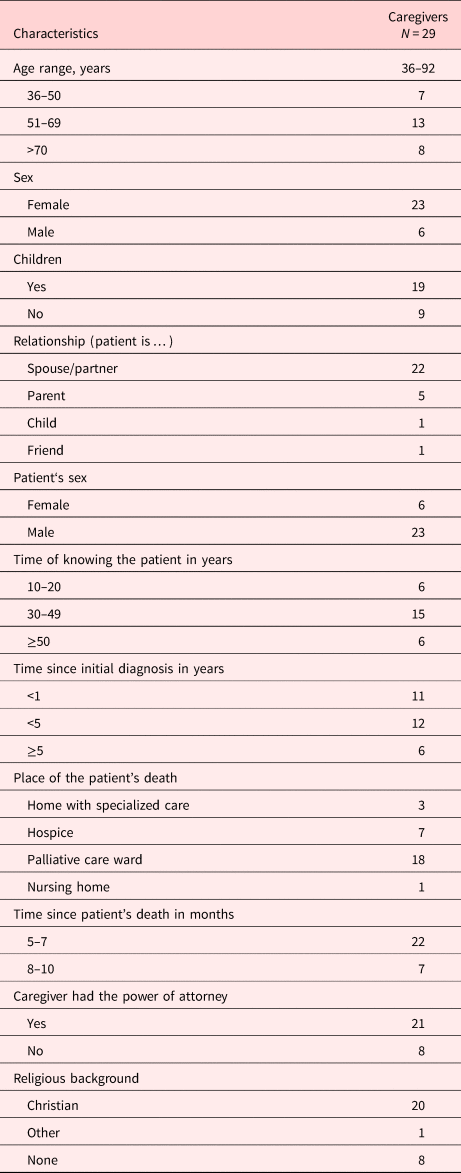

Both parent studies had been conducted at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany, in 2018 and reflected upon FCs’ experiences from the time of first diagnosis of incurable cancer up until bereavement. In the interviews, FCs were encouraged to reflect upon their experiences from the time of diagnosis up to bereavement in retrospect as all interviews were conducted after the patient's death. Primary data were collected by an experienced investigator and final year medical students after interview training, respectively. We included verbatim transcripts of all 29 interviews in the QSA. Participants’ characteristics are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics of participants

Data analysis

As suggested by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), thematic analysis was used to identify, analyze, and report themes within the preexisting interview transcripts. The software MAXQDA was used for data management and coding. Following initial familiarization with the data by reading and re-reading the transcripts, initial codes were generated systematically across both datasets by the first author (JW), who had not been involved in the primary studies. Through a discursive process of analysis, including inductive and deductive coding as well as memoing, the first and last author (JW and AU) reviewed and refined potential codes to create categories by grouping conceptually similar themes. Contextual information to enrich the analysis was provided by the last author (AU), who had been involved in the initial studies and was thus able to contribute a detailed classification of the original data. As proposed by Krippendorff (Reference Krippendorff2018), analysis explored implicit and explicit meanings in the data within the considered and systematically integrated, emphasizing the context of the time of diagnosis of incurable disease up to bereavement. Discussions within the research team were pursued until consensus was reached.

Results

Analysis identified four themes, associated with the presence of spirituality in FCs’ experiences: “Connectedness,” “Religious Faith,” “Transcendence,” and “Hope.” A fifth overarching theme was found in the context of the other described themes, which we titled “Ongoing integration of spiritual experience” (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Manifestation of spirituality among FC.

Connectedness

A subjectively experienced feeling of deep connectedness was described by FCs, which included feelings of belonging in the broadest sense. Analysis revealed that connectedness was experienced on different levels by FCs. In this respect, two aspects played a particular role in the representation of connectedness, enclosed by a third aspect regarding the meaning of connectedness. For one thing, FCs spoke of a “bridge” to the deceased in the context of connectedness to others. It became evident that this bridging could occur through the perceived connectedness to places, objects, as well as other persons.

“Meeting his (the deceased person's) friends is a bridge to him. My son, by the way, expressed that for him I represent a bridge to his father, too.”

The findings also suggest that subsistent connectedness with objects or places, that entailed a certain meaning to the deceased, were perceived as a notion of safety for FCs, as in the following narrative of a participant:

“The boat was the lifebelt, indeed. ( … ) People say you can sell it, but the emotional value is priceless. If we had sold the boat, my husband would be dead and so would I. The boat needs to be cared for; which I did and that was my safety.”

In addition, FCs described most obviously an ongoing integration and perceived presence of the lost person beyond the grave when relating to connectedness to other persons, in contexts such as shared memories:

“It is just pleasant to exchange views and memories of him (the deceased) with those people. To have common memories and to know, they know him, they knew him, they visualize him. And we all share this same picture of him. That is great!”

Feeling connected was outlined in the context of a stabilization regarding the unsteadiness of the overall situation as an FC. For example, it was described that FCs achieve a balance between holding on to the patient and letting the deceased go by focusing on the emotional attachment. The stabilization was described in form of a perceived protection, i.e., from the feeling of losing oneself during the time of caregiving as well as in the transition from caregiving to mourning and the coping process after the patient's death:

“The clothes, the personal things, I still hesitate. I have not quite found a conclusion. Then I tell myself, I do not have to. When I look at things like that, I cannot give them away. This bond protects me.”

Religious faith

Although not asked about directly, analysis showed a notable mention of a basic attitude toward religious faith by FCs. Descriptions in the context of faith were mostly related to religious beliefs, communities, and traditions. However, FCs determined different degrees of religious faith, and analysis indicated that faith held different values.

In narratives that demonstrated close ties to traditional, widespread belief structures, tight links to a religiously formed faith were described. These narratives revealed that some FCs felt strengthened by religious belief structures.

“Believing in heaven is quite fortifying.”

Analysis showed that the religious community, shared convictions, and well-known rituals represented an important helpful aspect for FCs during caregiving and especially during bereavement. In the analyzed narratives, rituals were identified as helpful in coming to terms with death and loss and were described as helping FCs attain a sense of closure:

“When attending the memorial service, all deceased were mentioned. Attending families, could light a candle and place it on a beautiful rack. From this day I got better. From this day ( … ) it felt like the breakthrough. I was able to conclude, that was good.”

In comparison, some narratives presented a more individualized shaping of religious faith, which contained less traditional rites, such as praying or attendance at church. Analysis showed that especially this kind of adjusted faith allowed for situational emphasis on certain mental pictures, i.e., the belief in a heaven, which was described as comforting by FCs:

“I am catholic, my husband was, too. I mean, I do not go to church or anything, it's not about praying every Sunday. Anyway, it certainly is a huge support that heaven exists.”

Furthermore, it became evident that some FCs expressed a complete rejection of religiosity without preceding enquiry of the topic by the interviewer. While some narratives revealed an indifference or amusement toward religious faith, others went as far as devaluating religiosity, where FCs voiced a strong personal aversion:

“This intensely devout touch … terrible. We [FCs and the deceased] both thought so. ( … ) There is this dominance of commoners that have always been illusory-religious.”

Transcendence

Another revealed theme was transcendence, described in the context of the overall situation that FCs found themselves in. The findings suggest a perceived widening of own experiences and sensory perceptions among FCs in the context of exceeding the immediately present circumstances and consequences.

“I was shocked, frightened and sad that he was in that condition. In that moment, however, I did not reflect the situation and future. There was more, on a new level, it was awkward.”

Furthermore, FCs described a perceived guidance by intangible phenomena, which were described as unfathomable:

“Incredible. It is unbelievable what happens in these situations, led by I don't know, any self-controlled mechanism or something, really amazing.”

Additionally, analysis showed that spirituality plays a role when it comes to transcending the burdensome vagueness of the overall situation and acquiring the ability to let go:

“I would have liked to have such a voice earlier ( … ) something like, when I said ‘I will carry on, keep going’, something that replies ‘You don't have to. It's okay to have a break’.”

Despite differing notions of transcendence, the narratives demonstrated commonalities when integrating the affirmation or (re)construction of meaning and purpose of life. The analyzed transcripts also implied that FCs were in a state of indecision and steady change of feelings, especially during the time of caregiving:

“There were no clear ups and downs, it was rather a limbo.”

Analysis showed that the simultaneous presence of feelings, such as anger, longing, and sorrow, unbalanced FCs. Furthermore, it became evident that the perceived limbo occurred in the context of tension between pursuing a preset course of action, the desire and concrete emotions:

“You're simply functioning, you get up, you go to work, get things done, you come over here (hospital) and you wait. But you know, the thing is, you are scared.”

In the context of insecurity and helplessness in the caregiving situation, FCs showed a longing for stabilizing clarity and a wish to conclude the overall situation.

Hope

Transcripts revealed that in the context of hope, expectations, and confidence in the inevitable or what is happening played a central role for FCs. It became evident that the present, immediate, and longer-term future were individually weighted and led to different orientations of hope. With a focus on the present, respondents’ descriptions revealed a hope for joint experiences with their loved one. Furthermore, hope was also described with reference to the remaining time with the patient in this context:

“Most of all, we appreciated that she (doctor) estimated his life time at a year at least. So, that it should be worth it, from a medical point of view, was good news.”

Furthermore, FCs described the hope for a “good” transition from this world into the hereafter for the patient, which was found in transcripts relating to the immediate future:

“His (the deceased) face was smoothed, there was a small smile. ( … ) He had changed completely. Good for me. I said he left us in a bad condition but arrived safe and sound apparently.”

Concerning hopes for the longer-term future, moreover, FCs spoke of a lasting connection and continuing presence of the deceased in life after the patient's death:

“The many matters, that make me say, what would my husband do now? ( … ) What would he advise me to do? ( … ) I do not have to handle things by myself. I mean, of course I do, but I include him, he is involved.”

Ongoing integration of spiritual experience

Alongside the identified four above-mentioned themes, transcripts provided the multiple descriptions of a fifth overarching theme, which we titled “Ongoing integration of spiritual experience”. Transcripts with reference to this subject broached the issue of shifts and alterations of viewpoints toward life in general or on certain levels of the described manifestation of spirituality. The findings suggest that FCs observed changes in individual, fundamentally anchored attitudes in the context of their role and experiences as a caregiver. Also, FCs’ descriptions implied an increasing self-awareness and appreciation of the finiteness of life.

“I've become way more laid-back, I feel a bit more easy-going now. It may sound silly, but I do enjoy several things more. I try to create time for myself, read a book, ( … ) you know, consciously. In the past, I did not worry about anything at all. Now, I know what it means to seize the day ( … ) that it can all be over any day.”

Furthermore, the analyzed narratives revealed modifications and adaptations in everyday life, such as the reduction of working hours in the context of spiritual experiences discussed above:

“I cut down on work stuff. I rather relish the moment. And the little things.”

Interconnectedness of findings

Even though we separated the spiritual domains for analytic purpose, it is worth noting that the discovered elements of spirituality appeared interconnected. Links between hope and connectedness as well as ties between religious faith and transcendence were closely intertwined in FCs’ experience. Furthermore, it became evident that the above-described spiritual elements oftentimes occurred concurrently with other spheres of life, for instance, emotional or social experience, which might not be perceived or assigned to spiritual experience consciously. Moreover, we found that the elements of spiritual experience are associated with FCs’ shifting spiritual attitude, partly resulting in an interconnectedness of the described themes and the continuous integration of spiritual experience in FCs’ life.

Discussion

The purpose of this secondary analysis was to gain insight into the manifestation of spirituality in a group of FCs of terminally ill cancer patients. We chose methods that allowed access to the presence of spirituality and an understanding of spiritual experiences in the life of FCs. Appropriate openness and flexibility were achieved through the approach of a thematic analysis, which supplies a detailed, nuanced description of data.

Our findings contribute to earlier research that underlines the significance and value of the complex spiritual dimension in the context of palliative care (Selman et al., Reference Selman, Brighton and Sinclair2018; Best et al., Reference Best, Leget and Goodhead2020). Connectedness played a meaningful role over the course of being FCs of a terminally ill person from the time of incurable diagnosis up to bereavement. Our findings showed that FCs felt connected to places and objects with a subjective meaning and also connected to other persons, i.e., in the context of sharing memories regarding the deceased. Deep interpretation was beyond the scope of our analysis, which strived for a thematic understanding rather than wide-ranging assertions. However, our findings indicate plausible functions of connectedness, such as representing a bridge to the deceased, which possibly contribute to coping among FCs. While much of the previous work described connectedness on a rather abstract level, like feeling connected to the sacred (Taylor and Mamier, Reference Taylor and Mamier2005), our analysis contributed to a tangible notion of connectedness from the FCs’ point of view. It appears that meaningful entities like places or other persons require particular attention in the context of care and support for FCs (Keskinen et al., Reference Keskinen, Kaunonen and Aho2019). Regarding this, professionals could yet be thought of as representing entities for connectedness, especially for FCs that lack social networks (Keskinen et al., Reference Keskinen, Kaunonen and Aho2019).

Available evidence regarding faith in the palliative care context appears slightly inconsistent. On the one hand, faith is described as supportive and contributing to meaning-making or acceptance during the experience of illness and death (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Leng and Namukwaya2017). On the other hand, studies have shown that individuals can feel abandoned or struggling with faith when facing situations like life-limiting disease (Ferrell and Baird, Reference Ferrell and Baird2012; Delgado-Guay et al., Reference Delgado-Guay, Parsons and Hui2013; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, Seah and Clayton2019). As a noteworthy aspect in our results, FCs discussed variable scopes of religious faith, while they did not broach the issue of change in attitudes toward faith (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Joseph and Linley2005) in the context of their experience as an FC. We found a strong identification with religious faith as well as a complete rejection. Even FCs who indicated refusal or renunciation of faith, still made faith a subject of discussion without being asked about it directly. Therefore, our results indicated that discussing religious faith can be important, even if, for some FCs, it means indicating not being concerned by religion at all.

Several articles discuss hope and spirituality in the context of palliative care, underlining the multidimensional nature and therapeutic value of hope (Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Pereira and Raffin2006). Likewise, we found hope to be a matter of importance for spirituality among FCs. In a study on hope in life partners of patients in palliative care, Kylma et al. (Reference Kylma, Duggleby and Cooper2009) differentiated between factors contributing to hope versus those undermining it. Referring to this, respondents in our analysis indicated contributing factors. Those were associated with different periods of time in life, which is in line with the related literature, indicating that hope represents rather a process than a state. Previous studies have found factors contributing to the hope of FCs in palliative care, including hope in the “here now” versus hope for the future (Herth, Reference Herth1993; Holtslander et al., Reference Holtslander, Duggleby and Williams2005). Even though the consideration of hope and fluctuations over time is deemed important with regard to emotional factors in palliative populations (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Tataryn and Clinch1999), few studies reflect upon the total time span of disease trajectory up to bereavement. Our findings add an additional distinction within future-related hope, namely hope in the immediate as opposed to longer term. This additional differentiation supports the notion that hope in palliative care should be seen as a process rather than an attainable state (Hegarty, Reference Hegarty2001). The majority of previous studies focus on patient hope (Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Gibson and Kramer2004) or the role of health professionals (Buckley and Herth, Reference Buckley and Herth2004), while less insight is available concerning FCs. Our results support the notion that being affected by incurable illness does not necessarily mean to live without hope (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Curtis and Patrick2002). This assumption appears to be true for the whole unit of care and not only for affected patients. Hence, the direct integration of hope into practical approaches and care concepts for FCs as well as the enhancement of hope across the whole process of care gain in importance.

Furthermore, we identified spiritual transcendence as an important factor for FCs. Just like the construct of spirituality itself, transcendence, as a significant element of such, remains hard to define adequately (Johnstone et al., Reference Johnstone, Cohen and Konopacki2015). Yet, transcendent experiences occur in considerations of spirituality. Our findings were in line with parts of a definition by Johnstone et al. (Reference Johnstone, Cohen and Konopacki2015), which refers to transcendence as a “sense of increased ( … ) connection with higher powers beyond the self, with higher power defined according to an individual's specific worldview” (p. 290). FCs in our analysis referred to something which exceeds the perceptible and is recognized as real, even though not really tangible.

In line with previous studies, it became evident that spirituality is a multilayered phenomenon and shaped individually among FCs. Corresponding to the method of secondary analysis, we extended the original study goal, where spirituality had not been an explicit topic of discussion. In light of this, it is notable that all interview transcripts showed links to spirituality. It is deducible from our findings that spirituality is omnipresent and impacts various levels of FCs daily life. Kellehear (Reference Kellehear2000) discussed that some spiritual needs may really be social or psychological needs, while other dimensions relate to the sacred or divine. Our five revealed themes suggest that spiritual aspects among FCs’ experience can overlap each other as well as other areas of life. Equally, it became evident that an ongoing integration of spiritual experience can foster or underpin FCs’ life on a whole new level. The fields of experience within spirituality among FCs turned out to be interconnected, which calls for a blended approach of care, including a wide range of topics to access. Even themes like connectedness, which may appear as an evidently social construct, can have strong links to spirituality for FCs. While it proved important to touch on different notions of spiritual experience, it can yet be reasonable to bear in mind that FCs themselves might not perceive social, psychological, and spiritual aspects separately or label spiritual needs as such.

This secondary analysis shows strengths and limitations. The chosen research method has been the object of criticism in previous contexts (Ruggiano and Paerry, Reference Ruggiano and Paerry2019). Secondary analysis, however, is not limited to quantitative contexts but increasingly promoted in qualitative research ( Dargentas, Reference Dargentas2006; Walters, Reference Walters2009).

Extensive methodological discussions are beyond the scope of this paper; hence, we only include the major limitations of our work below. Since both original datasets derived from the same study context (FCs of patients with incurable cancer), our findings may not be applicable across other populations and care systems. This limitation also arises out of the homogeneity of the studied population, which was predominantly comprised of female spouses of patients. However, careful use of the supra analysis design, combined with the involvement of researchers, involved in the primary research, and contributed to sticking to the principles of the original studies. Another limitation of this study is the fact that all statements occurred after the patient's death and reflected FCs experience in hindsight. Given that spirituality can evolve over time, the statements regarding spiritual dimensions could have varied if FCs had been interviewed across the course of their family members illness. Furthermore, despite the advantages of QSA, the findings could have been enriched if spirituality was a discussion topic in the primary research. We explored spirituality through the lens of family informants, in order to gain insight into FCs’ experience but did not have the chance to revalidate our findings with the participants. However, while previous studies mostly used mixed samples of patients and FCs, we narrowed our analysis to exclusively FCs’ experience for the benefit of highly focused results on an underrepresented study group. Hence, our results can be considered as preliminary findings and pave the way for in-depth studies on FCs’ spiritual needs.

Conclusion

Our data strengthen the importance of taking spirituality and/or spiritual needs of FCs into account, along with those of the patients, to adequately meet the concerns of the unit of care (Van de Geer and Wulp, Reference Van de Geer and Wulp2011). It should be kept in mind that spirituality can be both, a clearly discernible as well as an underlying phenomenon in the caregiving experience. Thus, clinical practitioners can pave the way for discussion and expression of wishes and needs for FCs by taking an open perspective on spirituality. Further approaches to meet spiritual needs of FCs should pay particular attention to the fact that spirituality can represent an important part of some FCs’ life all along, while in other persons’ life spiritual aspects manifest in the context of caring for a loved one or even for the first time after the patient's death. However, potential reservations and/or a vague accountability among professionals regarding the actively initiated discussion of spiritual needs with patients and caregivers pose an impediment in the holistic support of the unit of care. Hence, it seems essential to provide training and comprehensive information on elements and dimensions of spirituality to achieve profound understanding and enhance confidence regarding the topic among healthcare professionals in palliative care.

Further research is required to gain insight into FCs’ specific spiritual needs. Since most existing studies were cross-sectional in nature, future research should include longitudinal approaches to gain insight into FCs’ spirituality over a longer period of time.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude and respect to the family caregivers who took part in the primary research and to the researchers for sharing the collected data for the purpose of this secondary analysis.

Author contributions

AU participated in primary studies, interpretation of the results of secondary analysis, and revision of the manuscript. JW and AU devised the secondary analysis and main conceptual ideas. JW conducted secondary analysis, interpretation of results, and wrote the manuscript. AU contributed to analysis and interpretation of results. MTr participated in primary data collection and reviewed the manuscript. MTh participated in primary data collection and reviewed the manuscript. CB and KO participated in revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.