Introductions of invasive alien species have a major global impact on ecosystem integrity (Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, King, Strachan, Macdonald and Service2007; Pejchar & Mooney, Reference Pejchar and Mooney2009), with negative consequences for community structure and diversity that can persist for decades (Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, De León, González and Torchin2017). Developing countries undergoing rapid economic growth can be especially vulnerable to such introductions, driven by new commercial opportunities (Pelicice et al., Reference Pelicice, Vitule, Lima Junior, Orsi and Agostinho2014). In China the profitability of selling exotic species has led to substantial numbers being bred in captivity to supply demand for pets, Chinese traditional medicine, and food (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Gao and Zhan2015). Online trade, or e-commerce, has become a major distribution channel, exacerbating the spread of invasive species and challenging biosecurity (Lenda et al., Reference Lenda, Skórka, Knops, Moroń, Sutherland and Kuszewska2014; Humair et al., Reference Humair, Humair, Kuhn and Kueffer2015).

Although the slider turtle Trachemys scripta elegans (Ficetola et al., Reference Ficetola, Thuiller and Padoa-Schioppa2009) and snapping turtles of the genera Chelydra and Macrochelys (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Hasegawa and Miyashita2006), all native to the Americas, are amongst the most invasive exotic species, the market for these taxa and the extent of their colonization has not been assessed in China. Turtles are bred in freshwater aquaculture facilities in China, 65% of which are in the Yangtze river basin (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Xiong, Wang and Chang2009). This region is highly susceptible to the establishment of alien invasive turtles (e.g. T. scripta elegans, Xiao, Reference Xiao2015; Chelydra serpentina, Chen et al., Reference Chen, Lu and Li2017; Macrochelys temminckii, Chen, Reference Chen2017) because of the area's suitable climate and habitats. Here we evaluate how online trade (e-commerce) adds a new dimension to this problem, facilitating purchase of turtles, driving production in breeding facilities, and risking escape and release of turtles along all stages of the supply chain (Kraus, Reference Kraus2015). We document national online sales of live slider and snapping turtles via mainland China's largest domestic consumer-to-consumer internet trading platform, Taobao.com (a subsidiary of the Alibaba Group). We examine the spatial distribution of turtle sales to generate a sales map, and explore how this is associated with media reports of feral turtle populations in the Yangtze river basin, and provide recommendations for how to mitigate turtle trade and the establishment of invasive species.

We conducted three surveys (24 February–27 March 2017, 14 April–10 May 2017, 3–18 October 2017), searching for the terms ‘slider turtle, live’ and ‘snapping turtle, live’ (in Chinese) on Taobao.com. We included ‘live’ to distinguish animals traded, as opposed to toys, pet supplies, and similar items. To avoid recording a vendor's goods sold more than once, we re-inspected vendors after an interval of at least 30 days to see if they had made subsequent sales of additional goods. When new vendors comprised < 3% of total vendors on our list in each survey, we ceased searching for additional vendors, assuming we had accounted for the majority.

Taobao.com provides retrospective transaction information, including ‘species’ (which we verified from the description and photographs provided by sellers), ‘item location’ (i.e. site of origin of the sale, used to calculate freight charges, and which we presumed to be accurate), and ‘successful transactions’, which provided the number of individual animals sold during the 30 days preceding our inspection of Taobao trading records (one transaction equates to one animal traded). The destination of sales was not, however, included and thus did not form part of our analyses. Data were collected and analysed using prefecture as the administrative unit (mainland China comprises 334 prefectures, in 34 provinces, and four province-level municipalities). To determine whether the number of sales (log-transformed) were similar between neighbouring prefectures, which would suggest trading hotspots, we used Moran's I (Moran, Reference Moran1950) to assess spatial autocorrelation at 10 distance classes (42–3,482 km for the slider turtle and 42–2,937 km for the snapping turtle) using Spatial Analysis in Macroecology 4.0 (Rangel et al., Reference Rangel, Diniz-Filho and Bini2010).

To examine for any link (whether causal or coincidental) between areas where sales originated and sites where invasive freshwater turtles were recorded, we searched Baidu News (on 8 August 2018) for reports containing the search term ‘exotic, turtle’ (in Chinese) in the full text of articles for 2008–2018. We tested whether the proportion of prefectures reporting invasive non-native turtles were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in trading hotspots, using cross tabulation with a χ 2 test. We applied Yates’s correction for continuity because of the small number of news reports available.

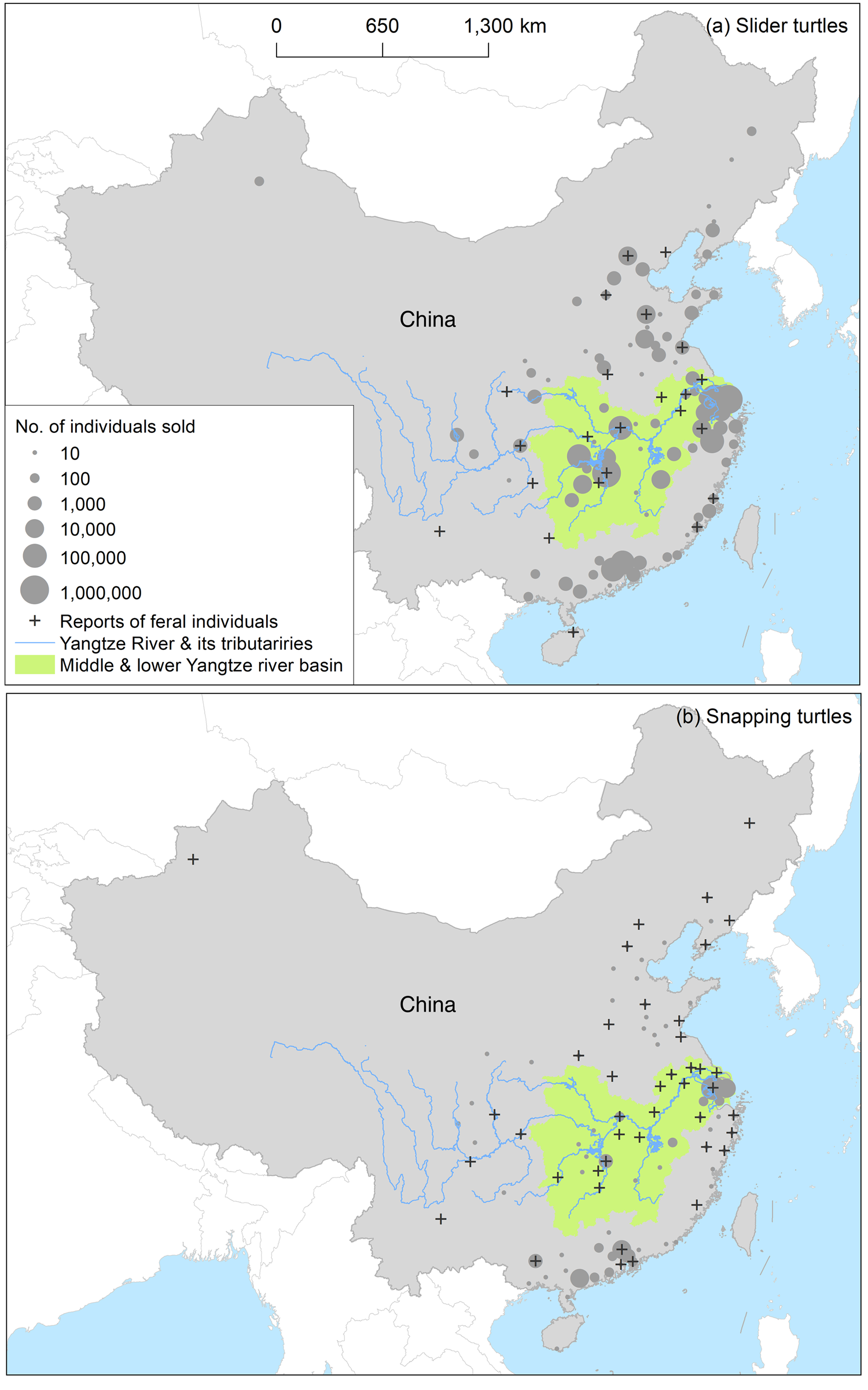

From the three surveys, each covering 1 month (30 days) of trade (i.e. monitoring 25% of total annual commerce), we recorded 840,193 transactions involving slider turtles (by 469 vendors) and 108,047 involving snapping turtles (by 472 vendors), which extrapolates to naive estimates of annual trade volumes of c. 3,360,000 and 432,000, respectively. Geographical patterns of sales were similar between taxa, although sales originated in only 106 of 338 prefectures and province-level municipalities (slider turtles in 89, snapping turtles in 70; Fig. 1). From the spatial correlation coefficient at the first distance class (P < 0.05) we found clustering for log-transformed regional sales of slider turtles (at distances of 42–339 km, involving 782 pairs of prefectures, Moran's I = 0.12) and snapping turtles (at distances of 42–304 km, involving 482 pairs of prefectures, Moran's I = 0.14). This revealed a sales hotspot, with 82.4% of slider turtles and 68.3% of snapping turtles sold from 26 and 17 prefectures, respectively. These prefectures lie in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze river basin, the predominant aquaculture region in China, from where turtles are bred and disseminated through wholesalers, retailers and consumer-to-consumer traders (Fig. 1). The majority of the sales of slider turtles originated from Shanghai (198,289 individuals), Suzhou (174,698) and Changsha (165,952), and of snapping turtles from Suzhou (53,572), Shanghai (12,620) and Changsha (3,806).

Fig. 1 The prefectures where (a) slider turtles Trachemys scripta elegans and (b) snapping turtles (Chelydra spp. and Macrochelys spp.) were offered for sale on Taobao.com and where invasive populations were reported during 2008–2018, and the middle and lower Yangtze river basin.

We found 30 news reports that mentioned invasive slider turtle populations, across 23 prefectures, 16 of which were amongst the 66 prefectures comprising the middle and lower Yangtze river basin; 14 news reports were amongst mainland China's other 272 prefectures (Fig. 1). Similarly, 74 news reports mentioning snapping turtles involved 42 prefectures in the Yangtze region, whereas only 26 reports were from elsewhere in China (Fig. 1). This indicates significantly more reports of invasive turtles in the Yangtze region (χ 2 with Yates's correction, P < 0.05, df = 1, for both taxa). Reports mentioned ‘ceremonial animal release’ events (12 for slider and four for snapping turtles) and reported predation on native species such as fish, tadpoles, small turtles and eggs of waterfowl (nine for slider and three for snapping turtles).

The estimated c. 3,792,000 turtles traded per year on Taobao.com, as extrapolated from our surveys, suggests that e-commerce is contributing to the purchase and release of potentially invasive turtle species in China. This number is greater than the c. 500,000 turtles sold from aquaculture centers in 2002 (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Parham, Fan, Hong and Yin2008). In addition to Taobao.com, other smaller e-commerce platforms (e.g. JD.com, 1688.com) also offer turtles for sale, and thus our findings provide an indication of only a portion of the e-commerce trade of freshwater turtles in China.

Hulme et al. (Reference Hulme, Bacher, Kenis, Klotz, Kühn and Minchin2008) identified six introduction pathways (release, escape, contaminant, stowaway, corridor and unaided) that can facilitate the establishment of alien vertebrate pest species (Kraus, Reference Kraus2015) such as invasive freshwater turtles. In addition to turtles that escape from aquaculture facilities (Casimiro et al., Reference Casimiro, Garcia, Vidotto-Magnoni, Britton, Agostinho and De Almeida2018), Buddhists release various exotic species (including turtles) deliberately, hoping to generate good karma (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Mcgarrity and Li2012). Eighty-eight of 123 Buddhist temple release event organizers surveyed in China released large numbers of turtles and other invasive species (e.g. American bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus, Asian swamp eels Monopterus albus, Oriental weatherfish Misgurnus anguillicaudatus, several Cyprinid species; Liu et al., Reference Liu, McGarrity, Bai, Ke and Li2013).

Currently, there are no specific regulations or legislation pertaining to importation, domestic trade and captive breeding of non-native turtles in China. Snapping turtles are promoted as food, as a source of medicines and as pets, under China's Ministry of Agriculture announcement No. 485, 2005. Preventing further introductions and regulating turtle trade is challenging, with options such as eradication, containment and control difficult and expensive to implement (Hulme, Reference Hulme2009). A multi-pronged approach is most feasible, managing risks from trade and tightening regulations, implementing punitive fines, and policing breeding facilities (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Parham, Fan, Hong and Yin2008) and importation (Perrings et al., Reference Perrings, Dehnen-Schmutz, Touza and Williamson2005). Given the massive volume of online trade in invasive species, including animals other than turtles (Lenda et al., Reference Lenda, Skórka, Knops, Moroń, Sutherland and Kuszewska2014), and plants (Humair et al., Reference Humair, Humair, Kuhn and Kueffer2015), and the consequent invasion risk, we recommend that including an ecological hazard warning should be compulsory for all advertisements for taxa known to be invasive. This should be enforced through amendments to advertising laws and/or through self-regulation codes of conduct implemented across the internet industry. We acknowledge, however, that attempts to regulate turtle breeding and trading could face resistance on both social and economic grounds.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support provided by the China West Normal University (Grant 17BO10).

Author contributions

Study design: ZMZ; writing: CN, CDB, DWM, ZMZ; data collection: SL, YZ, KJZ, FL; analysis: SL.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. The Taobao.com customers were anonymous and there was no invasion of personal privacy.