Introduction

The contemporary politics of many countries features discriminatory attitudes, rhetoric, and practices oriented against ethnic minorities. These reflect inequalities in the perception of foreigners in the host communities, rigid boundaries for integration, and different treatment according to the ethnic group of origin (Lafleur Reference Lafleur2013; Quillian Reference Quillian2006; Sheffer Reference Sheffer2003). Both in new and established democracies, an increasing number of parties with antiminority agendas successfully bring to the electoral arena concerns about pluralism and multiculturalism (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017). These criticisms target various groups of ethnic minorities despite heterogeneity in terms of the reason for being a minority (for example, migrant or historical), the length of stay, or the type of residency. In this context, extensive research has analyzed the phenomenon of ethnic discrimination, with a focus on the communities that are exposed to it. There is much attention to the institutional actions and discourses of politicians from the countries of residence (McMahon Reference McMahon2016) toward ethnic minorities, including framing from the media. At the same time, there is research about how parliamentarians from the home countries address the issues of their communities abroad, with an emphasis on policy making. More specifically, it covers the legal aspects and procedures related to human rights and freedoms, or on the maintenance and reproduction of the homeland’s culture (Laguerre Reference Laguerre2015).

Many of the existing problems faced by minority ethnic groups in the process of integration are related to discrimination (Ellermann Reference Ellermann2020; Hatch et al. Reference Hatch, Gazard, Williams, Frissa, Goodwin and Hotopf2016). In spite of this, we know little about how ethnic discrimination is approached in the countries of origin of those minorities (migrants or coethnics). It is relevant to understand how the members of Parliament (MPs) in the home country address the discrimination to which some of the citizens or communities of coethnics they represent are subjected. Beyond the traditional role in the “formation of laws,” parliaments are customarily depicted as arenas where elected representatives speak about the grievances of their constituencies (Martin, Saalfeld, and Strøm Reference Martin, Saalfeld, Strøm, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014). Given that voicing and responding to citizens’ needs and preferences are central tenets of representative democracy, parliamentary debates are forums that both create a link between voters and their representatives and organize the law-making process (Proksch and Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2015).

This raises the question about how likely contemporary legislators are to be responsive to the needs of the communities from abroad and to resident citizens. Studies of representation show that MPs tend to deal with the voters’ requests either by the anticipation of external rewards (for example, reelection) or by a sense of duty and an intrinsic satisfaction from responding to a specific input (Giger, Lanz, and de Vries Reference Giger, Lanz and de Vries2020). Similar assumptions seem be valid for nonresidents, especially in relation to their ability to decide a national election (that is, Italy and Cape Verde in 2006 and Romania in 2009). A recent study identifies several reasons for which states increasingly court and cultivate the loyalty of their migrants (Burgess Reference Burgess2020). However, with a notable exception (Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei Reference Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei2019), there is scarce research about how communities abroad are discussed in the parliaments of their home countries.

Considering the relevance of the parliament as a context of decision and discussion in democratic politics, it is useful to dive into the arguments that are exposed by elected politicians to identify which are the specific standpoints regarding the “people” who reside beyond the national borders. In line with Pedroza (Reference Pedroza2019, 80), we consider parliamentary discourses as political actions that describe and interpret an issue, have an internal logic of argumentation, and signify experience from a particular perspective (Fairclough Reference Fairclough1995) – and that open up spaces for reinterpretations and decision-making processes. We focus on the themes used by the MPs in their speeches about discrimination and the references (utilitarian, identarian, or moral-universal/governance-focused) used to voice and formulate potential solutions.

To address this gap in the literature, our article seeks to answer the following research question: how do Romanian parliamentarians address discrimination against Romanians abroad? We compare and contrast discrimination against two different communities: migrants and members of the historical communities in neighboring countries (that is, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, and Ukraine). We use inductive thematic analysis conducted on all the parliamentary speeches about discrimination of coethnics abroad in the lower House of the Romanian Parliament (Chamber of Deputies) between 2008 and 2020. A focus on parliamentary speeches is relevant because these are forms of social and political interactions that play a crucial role in the (re)production and legitimation of discrimination as an expression of dominance and exclusion (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Schiffrin, Tannen and Hamilton2003). Romania is the appropriate case study for this topic for several reasons: (1) it has many emigrants and historical communities; (2) the nonresident citizens play an important role in national politics; (3) there is documented discrimination against Romanian ethnics abroad; and (4) the Romanian state has engaged with these communities before (for details, see Research Design section).

This analysis advances our knowledge about how specific problems of communities abroad are addressed in the legislature of their home country in two ways. Empirically, it identifies what parliamentarians speak for, what they stand for, and how they refer to discrimination practices against their conationals living abroad. It identifies differences and convergence in their discursive practices. From a theoretical perspective, this analysis shows that the political rhetoric against discrimination can strengthen the relationship between the institutions in the home country and communities residing abroad. By talking about these issues in parliament, politicians make the story about discrimination newsworthy and create the necessary conditions for these issues to influence the national public debates and to gain international visibility.

The next section reviews the literature on the relationship between discrimination, migration, and diaspora. The second section provides details about the research design, with emphasis on case selection, data collection, method for analysis, and expectations. The third and fourth sections include the thematic analysis of the parliamentary speeches devoted to migrants or to the historic communities. The final section discusses the main findings of our study and links them with theory. The conclusions cover the most important implications of this analysis for the broader field of study.

Theoretical Approaches: Utilitarianism, Identity, and Governance

Discrimination is often considered a socially constructed outcome of processes and practices that create hierarchies and legitimize migrants’ unequal integration and access to the distribution of resources in host societies (Ellermann Reference Ellermann2020; Soysal Reference Soysal1994). It is oriented against both individuals and out-groups (Ellermann Reference Ellermann2020; Joppke Reference Joppke2005), with a heterogeneous repertoire of attitudes and practices that produce differences between the treatment that these individuals/groups receive and the treatment they would receive if they were members of the in-group (Quillian Reference Quillian2006, 303). Existing research identifies the roots of discrimination against minority groups in general in a series of attitudes and perceptions that range from security threats (including high rates of criminality) to stereotypes based on cultural and religious differences (Koopmans Reference Koopmans2015).

Discrimination occurs in different forms, such as stereotypes and prejudices reflected in the media and daily life, disadvantages on the labor market, or access to housing, education, health, or social security (Auspurg, Hinz, and Schmid Reference Auspurg, Hinz and Schmid2017; Zschirnt and Ruedin Reference Zschirnt and Ruedin2016). Political parties promoting xenophobic messages and antiminority (especially anti-immigrant) platforms enjoy relevant electoral support in an increasing number of countries that are destinations for migrants. They mobilize and exploit a diffused sense of (moral and cultural) incompatibility between immigrant behavior, norms, and values and those of the native population (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2008). Xenophobic discourse is used as a safety belt to prevent nationalistic self‐images from running into crisis and as part of a political struggle about who can access the collective goods of contemporary states (Wimmer Reference Wimmer1997).

Over the last decade, there has been an increased interest in the way that home countries engage with their communities of emigrants (Délano and Gamlen Reference Délano and Gamlen2014; Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014; Lafleur Reference Lafleur2013). The literature has often referred to the ties between states and their coethnic communities living beyond the national boundaries within a triadic configuration with a kin minority, an external national homeland, and the state where the coethnics reside (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 55). The evidence shows that kin states make assertive claims for a cultural and moral obligation to protect the interests of their kin and to prevent forms of discrimination, oppression, and even assimilation (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2011; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014). There is a wide range of remedial or compensatory policies and programs implemented by the countries of origin to protect the interest of the community of kin – for example, preferential access to citizenship (Knott Reference Knott2017b; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2010). The countries of origin are active against discrimination of their communities abroad (Laguerre Reference Laguerre2015; Délano Alonso and Mylonas Reference Délano Alonso and Mylonas2019), but the relations may vary considerably according to the types of diasporas (Sheffer Reference Sheffer2003). Various scholars have explored the activism of the countries of origin as being contingent on specific domestic interests and political opportunity structure (Burgess Reference Burgess2020, Tsourapas Reference Tsourapas2015; Délano and Gamlen Reference Délano and Gamlen2014) and chronicling a broad network of institutions, policies, and practices designed to reach out to these populations (Délano and Gamlen Reference Délano and Gamlen2014; Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014).

Utilitarian, identity-based, and governance explanations have been used to assess how states of origin engage with their communities abroad and to explain why they mobilize to support the claims of these communities. The utilitarian explanatory model considers home countries as strategic utility maximizers interested in the growth and stability of their own power (Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014). The engagement of state institutions or politicians is an instrumentally rational endeavor that pursues material interests in the form of remittances, donations, and investments. This model presents the diasporic communities as strategic assets in the domestic and foreign policy agenda – that is, mobilization in conflict management and peace-making processes (Gamlen, Cummings, and Vaaler Reference Gamlen, Cummings and Vaaler2019). The home countries are primarily motivated by “tapping” the economic, political, epistemic, or military resources of coethnics living abroad. Countries of origin may cultivate or harness certain communities more than others according to the estimations of the return (Ireland Reference Ireland2018; Lafleur Reference Lafleur2013).

According to the identity-based explanations, countries of origin engage with their communities to reincorporate “lost” members of the nation by supporting their spiritual, national, and cultural preservation and to reinforce their constitutive identity (Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014; Koinova Reference Koinova2018a; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2018). This engagement is pursued through both positive actions – support for educational programs and the organization of commemorative events or coordinated actions in supranational institutions – and the expression of discontent or protest against discriminatory practices in national and international forums (Koinova Reference Koinova2018a; Tsourapas Reference Tsourapas2015). The symbolic power of the communities abroad is fine-tuned by a pragmatic assessment of the foreign policy agenda. Countries of origin may privilege certain groups of coethnics abroad and ignore or downgrade the claims of others (Mylonas and Žilović Reference Mylonas and Žilović2019; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014).

The third model of explanations focuses on the engagement with emigrants’ issues through an institutional quest for a coherent system of global governance. Countries of origin govern the claims of their communities from abroad through bilateral treaties and increased reference to international norms and cooperation with international organizations (Gamlen, Cummings, and Vaaler Reference Gamlen, Cummings and Vaaler2019). The diplomatic network of embassies and consulates is an important support for countries of origin in addressing the claims and needs of coethnics in the countries of residence. The memberships of countries of origin in international organizations support national politicians in coordinated actions in favor of their (kin) communities. Politicians from several EU member states have often downplayed their engagement with intra-EU migrants in favor of guaranteeing the protection of ethnic kin in neighboring countries (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2018).

These three main, distinct rationales provide a nuanced understanding of home countries’ engagement rather than rigid and mutually exclusive explanations (Koinova and Tsourapas Reference Koinova and Tsourapas2018). In practice, elements of these three models are combined to a different extent. Home countries’ policies, practices, and institutions are politicized and therefore involve competition between different visions among political parties and transpartisan shared interests (that is, foreign policy agenda). This article seeks to identify what components of these theoretical models can explain the approach used by a home country (Romania) with respect to the discrimination faced by two types of coethnic communities abroad: migrants and historical ethnic communities.

Two Different Communities and Particular Expectations

The Romanian diaspora includes two communities: the new category of migrants, mostly related to labor, and the historical Romanian communities from neighboring countries (Bulgaria, Hungary, Serbia, Ukraine). The analysis does not include the Romanian-speaking community in the Republic of Moldova, due to its complicated status. This community accounts for roughly three-quarters of the country’s population, which makes it a majority that is not comparable to the other historical communities covered in the article. The members of this community have overlapping features: they can be treated as part of the historical community but also as migrants, if those individuals with Romanian citizenship – to which they have access – migrate to other countries.

To begin with the migrants, Romania has the highest increase in migration among the EU member states in the last three decades (Dospinescu and Russo Reference Dospinescu and Russo2018). After the regime change in 1989, Romanians had the possibility of going abroad for work or study. Travel abroad – especially to Western countries – was heavily controlled and restricted under communist rule. The Romanian migration between 1990 and 2020 can be divided in three waves. The first wave took place during the 1990s and is characterized by temporary migration driven by Romania’s economic instability and poor performance. The hardships of transition and the slow and problematic privatization led to unemployment and low living standards for many citizens. In this period, the migrants were usually men who worked abroad and provided financial assistance to their families in Romania (Sandu Reference Sandu2006). Among these, there were many temporary migrants who sought work in the Schengen area (Sandu et al. Reference Sandu, Radu, Constantinescu and Ciobanu2004).

A second wave of migration started in the early 2000s, coinciding with the opening of the Romanian negotiations for EU accession. This was supposed to happen in 2004, together with most other postcommunist countries, and visas were lifted a couple of years before that date. The visa-free regime marked an explosion in terms of Romanian migration: between 2000 and 2010, estimates indicate that the number of migrants tripled (Dospinescu and Russo Reference Dospinescu and Russo2018). In 2009 and 2010, approximately 26% of the Romanian households had at least one family member that migrated (Stănculescu and Stoiciu Reference Stănculescu and Stoiciu2012). A great deal of this second wave consisted of labor migrants, with Italy and Spain as preferred destinations (Suciu Reference Suciu2010). The main pull factor for Romanian migrants in these two countries was represented by the existing networks of conational migrants (Elrick and Ciobanu Reference Elrick and Ciobanu2009). This wave included seasonal, temporary, and permanent migrants. With respect to permanent migrants, there was a large increase of high-skilled migration in this time period: many Romanian professionals from different fields – especially from health services – went abroad (Dospinescu and Russo Reference Dospinescu and Russo2018).

The third wave started around the financial crisis in 2008 and was characterized by larger numbers of labor migrants (both high and low skilled) compared to the previous decade. The vast majority of Romanians who were abroad during the financial crisis did not return home when facing difficulties in the country of residence (Gherghina and Plopeanu Reference Gherghina and Plopeanu2020). Instead, they stayed and tried to identify solutions, or they migrated to another country. After 2010, the number of highly educated migrants increased dramatically, with many students seeking to complete their education or find a job abroad (Dospinescu and Russo Reference Dospinescu and Russo2018).

Among the historical Romanian communities, the one living in Bulgaria is quite old. The 1905 census indicates that roughly 80,000 Romanians lived there. Over time, their number dropped dramatically, and by 1965, only 6,000 were left. In 2001, Romanians did not appear as a separate category in the official statistics, and the 2011 census shows the presence of 891 Romanians in Bulgaria (Onețiu Reference Onețiu2012). The Bulgarian state does not recognize the status of minority for the Romanian community. Although there are some formal guarantees regarding their rights, the idea of Romanian identity is discouraged by the Bulgarian authorities. For example, the right to learn in their mother tongue is not granted (Novinite.com 2016).

Unlike in Bulgaria, the Romanian communities in Serbia, Hungary, and Ukraine include more individuals, and they are recognized as national/ethnic minorities. In Serbia, there are roughly 30,000 Romanians in four main regions (Vojvodina, Belgrade, Sumadija and Western Serbia, and Southern and Eastern Serbia) (Milosavljević, Medojević, and Jandžiković Reference Milosavljević, Medojević and Jandžiković2014). The Serbian Constitution grants rights to the national/ethnic minorities – for example, the right to learn in one’s mother tongue and the right to promote one’s identity. In practice, there were repeated violations against the Romanian ethnics by the Serbian authorities (Euractiv 2012).

According to data provided by the Romanian embassies, there are roughly 8,000 Romanians in Hungary and approximately 150,000 in Ukraine (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020). The Hungarian and Ukrainian Constitutions also recognize the national/ethnic minorities and grant their rights. Nevertheless, Romanians reported multiple violations of their rights, especially in education and their right to study in the mother tongue (BalkanInsight, January 24, 2020). The problems encountered by the Romanian communities in these countries vary – from the lack of educational units and access to the media in Romanian, to the inability to practice religion in their language – coupled with several assimilationist practices instrumentalized by the state authorities in the countries of residence (Ziare.com 2019).

Guidelines for the Research and Expectations

From a conceptual perspective, we follow the Weberian path (Reference Weber1978, 4), according to which social action cannot be understood without looking at the (subjective) meaning that actors give to their actions. In our case, it is possible to make intelligible the denunciation of discrimination in parliaments by looking the arguments and reasons that MPs give for their positions. However, the speeches do not allow the identification of a clear-cut distinction between extrinsic (connected to the anticipation of external rewards) and intrinsic motivations (the aim to connect to voters) (Giger, Lanz, and de Vries Reference Giger, Lanz and de Vries2020). The MP speeches can be made meaningful by looking at both the way discrimination is referred to and the group of reference associated with it.

The data we use guides us toward a description of who voices a specific concern regarding discrimination, and how this argument is presented. This analysis enables clarifying the way discrimination is referred to as well as the influence of partisanship. In line with the literature, we assume that MPs deliver speeches that do not conflict with their parties’ core message, and that right-wing MPs are more likely to be active on this specific topic (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014). Following the descriptive basis (the who and the how part), our analysis is guided by two expectations.

First, we expect that the denunciation of discrimination can be considered utilitarian if prevalently targeting those communities with a relevant economic, political, and epistemic potential to alter the dynamics of politics in the home country. However, do not expect to identify means–ends types of rationality overtly (that is, appeals to external votes, migrant-based financial development, etc.) (Burgess Reference Burgess2020; Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014). The institutional confines are particularly relevant to this point. The literature considers that parliamentary discourses are governed by both rituals and legal–rational regulations that induce in the MPs the awareness of acting for and in front of different audiences (Bächtiger Reference Bächtiger, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014). For this reason, parliamentary debates rely on the need for the participants to maintain credibility and a moral profile. We expect to see MPs fulfill the obligations defined by their institutional role and avoid explicit references to basic calculations of utility.

Consequently, the denunciation of discrimination complies with a pragmatic meaning if the MPs justify their position by referring to general duties and responsibilities as elected officials. Given the context of the discrimination – namely the Western EU member states – we expect the utilitarian focus on the community of nonresident citizens to be further justified with references to the growing production of universal moral principles and European standards of rights and justice. Intuitively, the use of arguments that celebrate the nation are compatible with the denunciation of discrimination faced by Romanian citizens in EU countries.

Second, we expect to observe identity-focused argumentation prevalently connected to those communities that are culturally/linguistically/spiritually similar by virtue of their coethnicity. This argumentation is compliant with the literature on trans-sovereign strategies, and the constellation of programs, policies, and institutions created to maintain and reproduce the nation across existing state borders (Csergo and Goldgeier Reference Csergo and Goldgeier2004, 26–27). In this case, we expect to see MPs explicitly connecting their argumentation with the need to foster political, cultural, and spiritual ties with kin communities recognized as important members of the national community by offering them advocacy and support. The MPs can introduce prevalently identity-focused justifications that rely on an idea of deterritorialized nationhood and “competing jurisdictional claims” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996), although without explicit territorial claims. Governance-focused justification can further legitimize this specific argumentation either through references to bilateral treaties or more general international norms.

Research Design

Romania is the appropriate case study for this topic for four reasons. First, the country has an extensive share of migrants – one of the largest among the EU countries in the last two decades (Dospinescu and Russo Reference Dospinescu and Russo2018) – and large historical communities of coethnics in several neighboring countries. Second, nonresident citizens play an important role in national politics. For example, they had a direct influence on the results of the 2009 and 2014 presidential elections (Gherghina Reference Gherghina2015) and have participated actively in the antigovernment protests over the last decade. Consequently, Romanian politicians turned their attention toward them, and political parties developed organizations abroad to attract their votes. Third, there is documented discrimination against Romanian ethnics abroad. This came either in institutional form, such as the 2010 decision of the French government to deport Roma originating from Romania (Balch, Balabanova, and Trandafoiu Reference Balch, Balabanova and Trandafoiu2014), or in the public rhetoric that ascribed Romanian immigrants different characteristics at odds with the locals – for example, crime trafficking and abuse of welfare systems (Knott Reference Knott2017a; Light and Young Reference Light and Young2009).

Fourth, the Romanian state has engaged with these communities in the form of supporting institutions, programs, and policies aiming at preserving the specific ethnic ties, eventually broadened to the communities of the emigrants and their descendants (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2018). Postcommunist Romania defends the so-called kinship principle and recognizes as “ethnic relatives” those groups that, although consisting of citizens of other (neighboring) states, also share cultural, linguistic, and religious ties with the “Romanian national community” (Dumbravă Reference Dumbravă2014). These “ethnic relatives” have access to a wide array of benefits (that is, scholarships, programs in support of cultural, linguistic, and religious reproduction), financial support for media in Romanian language and for the creation and maintenance of associations promoting Romanian culture, linguistic and spiritual reproduction, advocacy in international forums or in bilateral relations aiming to improve their rights in the home state, etc.Footnote 1

This study uses inductive thematic analysis based on all speeches related to discrimination against Romanians abroad in the Romanian Chamber of Deputies (Appendix 1). We focus on the last three legislative terms: 2008–2012, 2012–2016, and 2016–2020. All speeches are publicly available on the Chamber’s website.Footnote 2 We start the analysis with 2008 because it coincides with the allocation of the first parliamentary seats for diaspora.

The speech is the unit of analysis, and each speech was assigned one theme. Despite the variation in length, there is no speech with more than one theme. The process of data collection, theme assignment, and analysis were organized in three stages. First, the authors of this article selected all the speeches related to discrimination between 2008 and 2020, and we read them individually. These were selected from the universe of speeches about Romanians abroad delivered during broader debates in the plenary sessions. Second, each speech was coded separately by all authors, a theme was assigned, and the individual lists of themes were compared. Third, we compiled the final list of themes included in our analysis. To ensure intercoder reliability and consistent coding across speeches, we used percent agreement measurement. We calculated each time the average pairwise percent of agreement, and we did not opt for a theme until the result of the calculus was higher than 90% pairwise agreement.

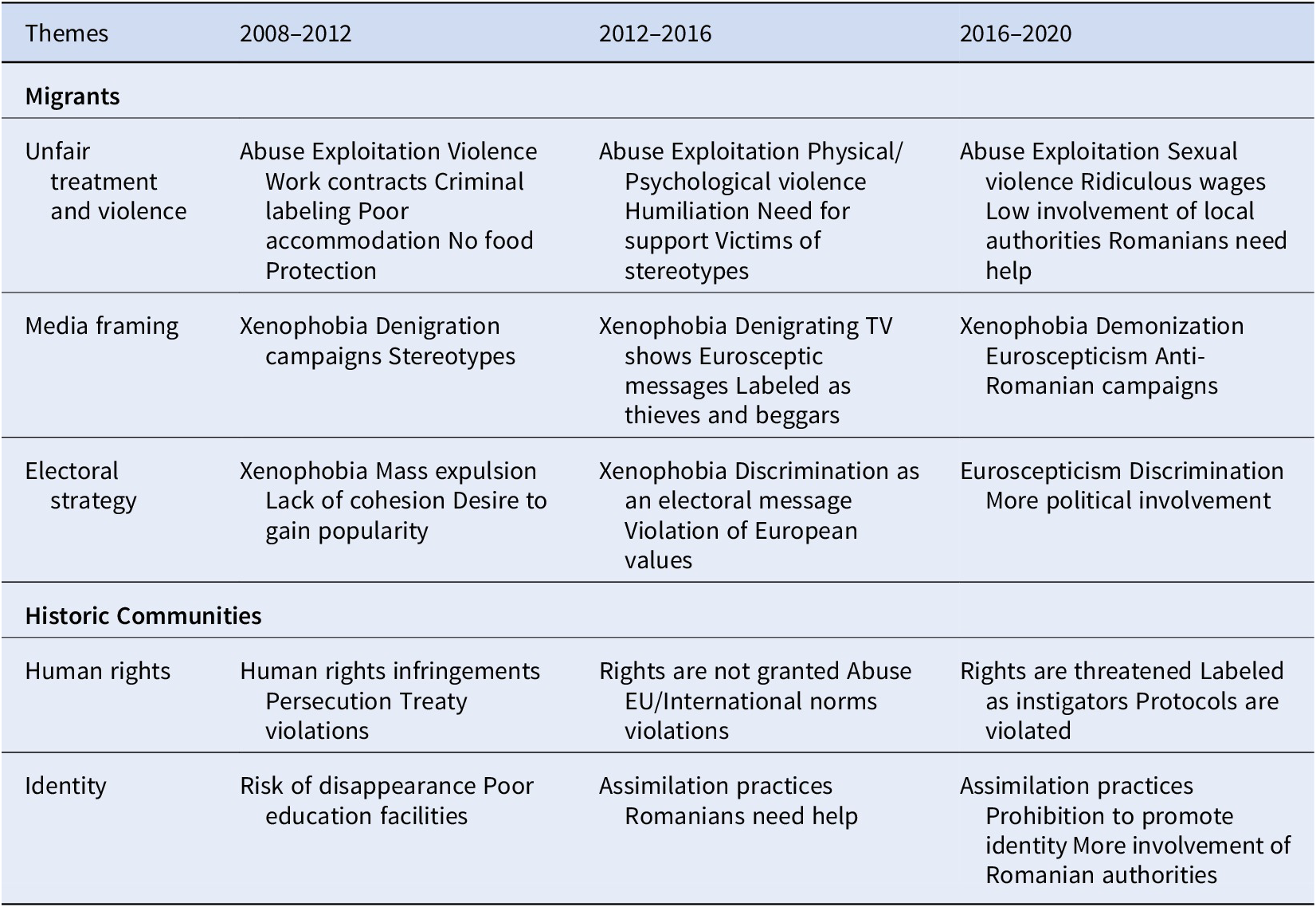

In total, there are 123 speeches distributed as follows: 30 (2008–2012), 56 (2012–2016), and 37 (2016–2020). The length of speeches ranges from 239 to 1,681 words for the first term (average length: 561 words), 163 to 1,548 for the second term (average length: 613 words), and 216 to 1,380 for the third term (average length: 541 words). The speeches (Table 1) refer to the discrimination against Romanian migrants (73 speeches, 60% of the total) and against Romanians belonging to historic communities in the neighboring countries (49 speeches, 40% of the total). Many speeches about the discrimination against migrants refer to the situation in particular countries such as the United Kingdom (19), Italy (13), and France (8). These are among the favorite destinations of Romanian migrants. Other speeches referring to migrants approached either the theme of discrimination in general terms and/or the situation of Romanian migrants in other EU countries (Spain, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and the Scandinavian countries). Parliamentarians often referred to cases of human rights infringements, xenophobic attitudes, and discrimination faced by Romanian children in schools (Aledin Amet, September 8, 2009; Cosmin Necula, June 25, 2015; Daniel Oteșanu, February 6, 2019; Aurelian Mihai, September 27, 2016; Vasile Axinte, May 23, 2017; Andrei Deniel Gheorghe, June 13, 2017). The discrimination against Romanians from the historic communities focuses on Ukraine (27), Serbia (15), and Bulgaria and Hungary (seven speeches in total for both). This distribution indicates considerably fewer speeches reflecting issues of discrimination in the EU member states.

Table 1. An Overview of the Discrimination Themes Covered by the Parliamentary Speeches

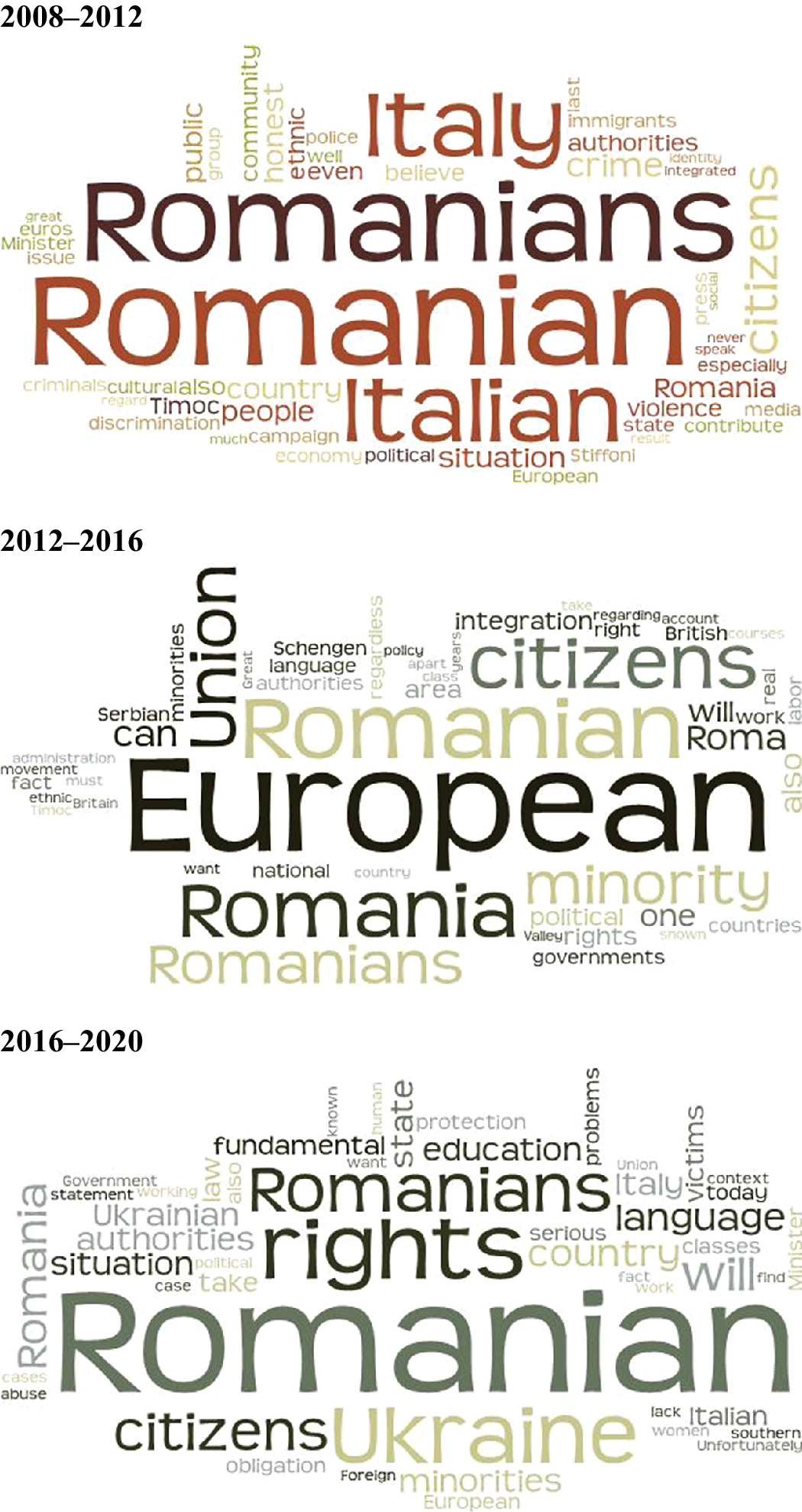

The word clouds derived from the speeches analyzed in this article (Appendix 2) confirm, to a large extent, the themes presented in Table 1. The word cloud related to the first legislature emphasizes that the MPs usually spoke about the abuses, discrimination, and violence faced by Romanian emigrants; the MPs’ speeches focused especially on one country (Italy), as will be reflected in the following section. The word cloud for the second term in office has a broader focus and refers broadly to Europe rather than a specific country. Most of the parliamentary speeches between 2012 and 2016 touch on Romanians’ integration in those countries, issues related to citizenry, and restricted access to workplaces. In the third term (2016–2020), the MPs’ speeches focus extensively on the rights and elements of identity, such as language. The countries of residence for historic communities are more prominent, and emphasis is given to the problematic situation of Romanians in Ukraine or the frequent infringements of cultural rights in Serbia. The following section provides more detailed information about the themes and their use in individual speeches.

Discrimination against Romanian Migrants

The parliamentarians elected for diaspora were active in the second and third terms in office. In the first term (2008–2012), one MP elected for diaspora, Mircea Lubanovici, delivered one speech. In the second term, three parliamentarians delivered approximately one-third of the total number of speeches: Aurelian Mihai (14), Ovidiu Alexandru Raețchi (2), and Eugen Tomac (1). A similar share of speeches is delivered by two MPs elected for diaspora between 2016 and 2020: Constantin Codreanu (10) and Doru-Petrișor Coliu (4). Even though parliamentarians were constant in delivering their speeches, they were more active when something harmful to Romanians abroad took place. For instance, most speeches about the Romanians in the United Kingdom were around the lifting of restrictions on the labor market for Romanians (that is, January 2014) and denigration campaigns against Romanians. The same happened with respect to Italy (for example, the wave of violence in Europe that arose after 2009), France (for example, the 2010 expulsion of Roma ethnics), or Ukraine (that is, the 2017 passing of the bill on forbidding the use of Romanian in schools). As Table 2 indicates, the political parties address these issues to a similar extent. There is no bias toward government or opposition parties. Similarly, there is a balance in addressing most themes across the terms in office.

Table 2. The Distribution of Themes across Terms in Office and Parties

Note: In 2016–2020, no parties addressed the media framing and electoral strategy themes.

Unfair Treatment at the Workplace and Violence against Romanian Migrants

Discrimination and xenophobic attitudes against Romanians abroad are directed not only at migrants but at those who reside in the host countries for purposes other than work (for example, students, visitors). The parliamentarians support the Romanian diaspora through their discourses and condemn the abuses faced by Romanians in the host countries. Apart from the desire to defend their conationals and the duty to take a stance against human rights infringements, parliamentarians look for gaining support from them during elections. Therefore, parliamentarians’ discourses are interconnected with the utilitarian model presented in the theory section.

The MPs emphasized that migrants – either nonqualified or professional workers – are discriminated against and abused by their foreign employers. Physical and mental violence, noncompliance with employment contracts, ridiculously low wages, abuses, forced work, and unfair employment conditions are just a few of the challenges faced by Romanian workers abroad (Constantin Dascălu, September 28, 2010; Aurelian Mihai, February 17, 2015; Aurelian Mihai, September 24, 2015; Doru Pretrișor-Coliu, March 14, 2017; Corneliu Bichineț, March 21, 2017). Some parliamentarians mentioned cases in which Romanian women were sexually abused in the southern part of Italy but refused to testify against their assailants because of the fear of losing their jobs (for example, Silviu Dehelean, March 21, 2017). Other parliamentarians took a general approach and said, for instance, that “from employees with contractual rights and obligations, Romanians have become mere slaves, accommodated in tents, without hygienic conditions, without food, and at the end of the work, they did not receive the established salary” (Cosmin-Mihai Popescu, April 19, 2011). Even though there were few speeches in this regard, some parliamentarians were vocal and emphasized that nationality makes a difference. For example, one argued that “another case that struck the public opinion in Romania and France refers to the Romanian doctor who claims that he was fired from a hospital in the south of France because of his nationality” (Marius Cristinel Dugulescu, September 27, 2011).

Nonworkers face different forms of discrimination and violence. For instance, one speech explicitly claims that “three Romanian citizens, students at a prestigious university in France, were the target of unscrupulous insults….and imprisoned only for speaking their mother tongue in inappropriate circumstances, in the opinion of the French police” (Daniel Buda, September 27, 2011). Another parliamentarian is equally explicit and argues that “12 Romanians, including a woman who arrived in England for free medical care, were arrested in London, and the wave of political statements raises big questions and multiple controversies” (Tudor Ciuhodaru, February 4, 2014). Moreover, there were reported cases of physical violence against Romanian citizens in France and Italy. One parliamentarian stated that a Romanian citizen “was brutally beaten after more than 12 people assumed he was a criminal. They assumed! They did not know for sure!…The case appeared in the press due to the excessive brutality and how this 16-year-old man was also found by a French citizen” (Aurelian Mihai, June 24, 2014). Another said that “a 37-year-old Romanian was savagely beaten by four people after which he was abandoned in the street. The episode took place last night in Parè di Conegliano” (Oana Niculescu-Mizil Ștefănescu, March 31, 2009).

Romanians abroad are perceived as thieves, criminals, or Roma ethnics, and this stereotype could explain the anti-Romanian attitudes. Parliamentarians outlined that foreigners develop hostile attitudes against Romanians because they make no distinction between well-integrated, honest workers and criminals (Mircea-Gheorghe Drăghici, March 3, 2009), and because “the stigma that the Roma group carries with it also affects Romanians, especially if we think about the wave of anger in Europe aroused by the explosion of violence and crime” (Danuț Liga, February 24, 2009).

Romanian Migrants and Media Framing

Foreign media is used often to discriminate against Romanians abroad, and these initiatives are supported by both politicians and civil society. Romanian parliamentarians condemned the European states that denigrate Romanians via the media and noted that these attitudes are not beneficial for European integration (Ninel Peia, September 18, 2013; Aurelian Mihai, October 8, 2013; Iuliu Nosa, October 15, 2013; Mircea Man, February 24, 2015). However, Italy and the UK provided more specific evidence in this regard.

Italy started a campaign of discrimination against Romanian migrants as of the beginning of 2009. The campaign was supported by politicians as well as print media and local television stations. Italian senator Stiffoni stated that “Romanians are drunkards, violent, murderous, exploiters of minors who go to Italy only to commit crimes. In an equally aggressive tone, Italian Minister of Reforms Roberto Calderoli demanded the “castration of Romanians who commit rape” (Viorel Arion, February 24, 2009). Moreover, local television stations (for example, Telenuovo, Telenordest, Rete Veneta, or Antenna 3) “presented the disastrous situation of some suburbs in which Romanians are indicated by residents as the main cause of the dramatic deterioration of public safety, and the images from Padua and Vicenza are an eloquent example of this” (Mircea-Gheorghe Drăghici, March 3, 2009).

In the UK, the discriminatory campaigns were triggered by the lifting of restrictions for Romanians on the British labor market in 2014. Since 2013, politicians and the media supported by British citizens promoted denigrating messages toward Romanians, and they advanced initiatives against labor market liberalization. British citizens tabled a petition and asked their government to extend the labor market restrictions for Romanians and Bulgarians by another five years, which was signed by more than 120,000 Britons who had been influenced by the Eurosceptic parliamentarians (Ana Birchall, March 26, 2013). Similarly, the Daily Express launched a public petition for influencing Prime Minister David Cameron to extend the restriction after December 31, and the Daily Mail warned that thousands of Roma ethnics would come to the United Kingdom to benefit from British social services (Miron Alexandru Smarandache, November 19, 2013). Channel 4 portrayed the so-called Romanians’ life in the UK through a documentary, but its real purpose was to denigrate the image of Romanians because it focused on “the poorest and least educated Romanian immigrants in the UK who cannot find work or who are there to benefit from social services,” but it ignored that “almost 80% of adult Romanians in the UK have jobs and pay their taxes” (Florin-Alexandru Alexe, February 24, 2015).

Romanian parliamentarians manifested their discontent regarding the discriminatory campaigns in Italy and the UK. According to some of them, “the reaction of the Italian press and the political class toward Romanians, in general, is exaggerated and xenophobic. It is a campaign to discredit and manipulate the Italian society for purely electoral purposes” (Viorel Arion, February 24, 2009). They also stated that the position of the British government toward Romanians was discriminatory once speculations were advanced that Romanians would take the jobs of British nationals when the labor market was liberalized (Ana Birchall, March 26, 2013). Another MP stated, “I feel insulted as a European citizen for the way we are treated, whether it is the tabloid press in the UK or certain politicians in Western Europe….political decision-makers in Bucharest must defend Romanians in the diaspora” (Aurelian Mihai, February 4, 2014). Along similar lines, another parliamentarian argued, “I believe that we need concerted action by the Romanian authorities, starting with the president of the country, to stop such negative messages from our compatriots in European countries, not only in Great Britain” (Ion Diniță, February 24, 2015).

Discrimination as an Electoral Tool

The anti-Romanian campaigns are used by politicians who promote Eurosceptic attitudes for electoral purposes and for gaining popularity during elections (Eugen Constantin Uriec, October 1, 2013; Cosmin Necula, October 1, 2013; Ana Birchall, October 15, 2013; Camelia Khraibani, March 25, 2014). Romanian MPs expressed their discontent about such actions and condemned the way in which politicians from Italy, the UK, and France utilize denigrating discourses about Romanians for purely political reasons. For example, one parliamentarian said, “I believe that we can pinpoint the source of the Eurosceptic and discriminatory actions and statements of some British politicians.…Electoral interest prevails even in states with a long democratic tradition such as the UK” (Ana Birchall, December 17, 2013). Consistent with this view, another MP argued, “at the origin of the Italian scandal targeting immigrants, especially Romanians, are reasons for Italian domestic policy.…the aim was to divert public attention from the demonstrated inability of Italian state institutions to prevent crime and social slippage” (Ioan Stan, March 3, 2009).

In addition to the examples from the UK and Italy, Romanian MPs condemned President Sarkozy’s actions directed at Roma ethnics who are Romanian citizens. Some emphasized that the initiatives of French authorities to expel Roma ethnics are discriminatory and against the values of the EU. French politicians stated that Roma camps are sources of criminality and threaten citizens’ security and public order. However, most Roma ethnics targeted by Sarkozy’s expulsion policies were not listed as criminals, and this is proof that France treated the Roma differently from other European citizens (Cristian Rizea, September 7, 2010; Constantin Dascălu, September 28, 2010). Moreover, Sarkozy increased his popularity through his expulsion policies and many French citizens – roughly half of them – supported these initiatives (Nicolae Păun, September 7, 2010; Cristian Rizea, September 7, 2010; Constantin Dascălu, September 28, 2010).

Sarkozy was not the only politician who promoted discriminatory attitudes against Romanians. One parliamentarian expressed his discontent regarding former Prime Minister Valls’s statements. He said, “You are not allowed to come in front of the world to say of a minority that it has ‘a vocation to be sent back to its country of origin’….You are the least European figure I have ever met in this European community, Mr. Manuel Valls” (Cosmin Necula, October 1, 2013). How the Roma were treated by France accentuated the dissatisfaction of Romanian parliamentarians, who said that “the current situation generated by the expulsion of Romanian citizens of Roma ethnicity from the French Republic is a crisis situation…Romanian authorities must identify quick solutions to prevent the worsening of the situation of Romanian citizens abroad” (Claudia Boghicevici, September 28, 2010). Some of them explained that French authorities use arguments to enforce the idea that Roma do not respect European values and are prone to crime, framing the idea that they are responsible for most of the crimes and offenses in France (Nicolae Păun, September 7, 2010). Others emphasized that all European citizens have the right to move freely throughout the EU and that the hostile attitudes toward the Roma reflect France’s disinterest in finding solutions for their integration (Cosmin-Mihai Popescu, September 7, 2010; Iuliu Nosa, October 15, 2013).

In addition to these lines of arguments, one parliamentarian strongly opposed to the discrimination of Romanian migrants as a theme for enhancing political popularity said, “We must be able to deliver a unitary message externally….We must no longer let foreign politicians use Romanians to promote their extremist policies or to get votes!” (Ana Birchall, October 15, 2013). Continuing the same line of argumentation, another MP stated, “I am confident that Romania, through the competent institutions, will do everything possible for our citizens to be safe, to have equal rights with others, and to be respected and listened to” (Natalia-Elena Intotero, April 4, 2017).

Discrimination against Romanian Historical Communities

Romanians in Serbia, Ukraine, Hungary, and Bulgaria are discriminated against, even though they have lived there for generations. They are the subject of assimilationist practices, and they face plenty of human rights infringements. Even though parliamentarians have treated the situation of Romanians there on an individual basis, some of them have approached it from a general perspective, stressing that “tens of thousands of Romanian speakers as a mother tongue form Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, and Ukraine…face great difficulties in their attempt to preserve their cultural and linguistic heritage…and to send their children to schools with teaching in Romanian” (Cornel-George Comșa, February 24, 2015).

Serbia and Ukraine (that is, two candidate countries for EU accession) were singled out by parliamentarians as being the places where Romanians face the highest level of discrimination. Their discontent was fueled by the number of Romanians there and the violation of the minority-protection protocols signed between Romania and those two countries. As some parliamentarians mentioned, the number of Romanians in the Timoc Valley (Serbia) vary between 250,000 and 300,000 (Dan-Radu Zătreanu, June 22, 2010; Gigel Sorinel Știrbu, June 4, 2013; Ana Birchall, March 31, 2015), and in Ukraine, there are over 400,000 Romanians (Cornelia Negruț, March 11, 2014; Răzvan-Ilie Rotaru, September 19, 2017; Constantin Codreanu, November 21, 2017).

Other MPs emphasized that in 1997 Romania signed a treaty with Ukraine, which provided strict rules regarding the rights of Romanian minorities. In spite of this, the number of Romanian schools in Ukraine has been reduced to half in the last 20 years (Andrei Daniel Gheorghe, September 13, 2017), or they stated that Ukrainian attitudes regarding Romanians violate the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: “under this convention, states undertake to recognize the right of any person belonging to national minorities to learn in his or her mother tongue” (Vasile Axinte, September 13, 2017). Moreover, the Protocol on National Minorities, signed between Romania and Serbia in March 2012, underlined the right of Romanians in Eastern Serbia “to be represented in the Parliament of the Republic of Serbia just as the Serbian minority in Romania is represented in the Chamber of Deputies” (Mircea Lubanovici, March 6, 2012).

Although compliance with the provisions of the protocols is mandatory for the accession of the Serbia and Ukraine to the EU, their attitudes toward Romanian communities are contrary to this objective (Matei-Adrian Dobrovie, March 14, 2018; Eugen Tomac, March 14, 2018; Andrei Daniel Gheorghe, September 13, 2017). Parliamentarians underlined the frequent violations of the protocols and presented the pitiful situation of the Romanian communities in both countries. For instance, it was stated that “anyone visiting the Romanian historical community in the Timoc Valley will be shocked by the illegal character that the Serbian state has given to any Romanian activity in the region” (Mihai-Bogdan Diaconu, December 17, 2013) and that “the Romanian minority in Serbia risks, more than ever, losing its own identity by being forced to disappear through gradual division into a new ethnic group in Eastern Serbia” (Cristian Rizea, February 28, 2012). On top of that, the inability to speak and learn in their mother tongue, lack of access to the media and religious services in Romanian, and permanent police surveillance were listed among the human rights infringements of Romanians in Serbia. Consequently, Serbian authorities are more likely to erase Romanians’ identity and to assimilate them rather than granting their fundamental rights (Florin Postolachi, May 18, 2010; Dan-Radu Zătreanu, June 22, 2010; Gigel Sorinel Știrbu, June 4, 2013; Constantin Codreanu, May 23, 2018).

The situation of the Romanians in Ukraine is not different from those in Serbia. Romanian MPs expressed their discontent toward a Ukrainian bill issued in 2017 that prohibited national minorities from studying in their mother tongue, including Romanian. One of them said that “the new law in Ukraine practically abolishes Romanian language education in the upper and middle classes, as long as the general rule is that the education system in Ukraine will be conducted only in the state language” (Vasile Axinte, September 13, 2017), and others labeled this initiative as anti-European and as an act of forced Ukrainization (Constantin Codreanu, March 6, 2019; Constantin Codreanu, October 8, 2019; Andrei Daniel Gheorghe, October 8, 2019). Moreover, Romanians in Ukraine who protested against the law were labeled instigators and promoters of separatist movements. Similarly, the same label applies to most of the Romanians’ initiatives of promoting Romanian culture in Ukraine (Constantin Codreanu, December 6, 2017; Ștefan Mușoiu, February 28, 2018; Andrei Daniel Gheorghe, October 8, 2018).

Other parliamentarians were firmer. One stated that “Romania’s support for Ukraine in the European course must be strongly conditioned by the civilized and respectful treatment applied to the Romanian domestic minority at European standards” (Constantin Codreanu, September 13, 2017). Another said, “If, in the shortest time, this situation is not resolved…ask my Social Democrat colleagues in the European Parliament to convey to all the member states of the European Union the termination of the Association Agreement between the European Forum and Ukraine” (Răzvan-Ilie Rotaru, September 19, 2017).

Unlike Serbia and Ukraine, Hungary and Bulgaria are EU members, and this could explain why Romanians there do not face similar levels of discrimination as in the first two countries. However, despite EU membership, Romanians in Hungary and Bulgaria still face several problems. One parliamentarian said that “Romanians in Hungary and Bulgaria, neighbouring and allied states, EU and NATO members, continue to be the subject of assimilationist policies and practices in contrast to the treatment applied by the Romanian state to the Bulgarian and Hungarian minorities” (Constantin Codreanu, May 23, 2018), whereas others were more specific: “Romanian education in Hungary is very deficient, being the most important cause of the loss of the national identity of Romanians….Regarding the programs for the Romanian community,…26-minute programs in Romanian are broadcast weekly… at a time that does not allow a large audience….A problem that created the dissatisfaction of Romanians in Hungary is the removal from the schedule of programs broadcast on the cable of the only program in Romanian, TVR1” (Gheorghe-Mirel Taloș, April 5, 2011).

Similarly, the educational system for Romanians is underdeveloped in Bulgaria, and initiatives of promoting their cultural identity are not encouraged by the Bulgarian authorities. Nevertheless, the recognition of the right to study in Romanian is considered to be essential for the preservation of the Romanian identity in Bulgaria, and it is a tool that can strengthen bilateral relations (Daniel Buda, April 19, 2011; Nicolae-Daniel Popescu, March 20, 2019).

Unlike Romanian migrants, about whom parliamentarians’ discourses were connected to a utilitarian model, Romanian historical communities represent another kind of interest for Romanian politicians. Instead of embracing utilitarian motivations in their discourses, the MPs embraced those related to an identity-based and governance model. Therefore, parliamentarians were more likely to advocate for the observance of the Romanian communities’ rights (for example, identity and culture promotion, the use of mother tongue, etc.) to promote a stance of respecting national/ethnic minorities’ rights and to raise the issue of human rights infringements in the international forums rather than concentrating on the financial or electoral benefits provided by their implication in the protection of Romanians abroad.

The different practices of discrimination reflected in the MPs’ speeches (for example, cultural and identity rights infringements; media and political stigmatization; noncompliance with contractual obligations; physical, psychological, or sexual violence) were presented in similar ways. The MPs did not use specific speaking patterns for discriminatory practices but rather used generalized language when presenting such issues. They usually emphasized the context, place, and the subject(s) associated with a given discriminatory practice and insisted that these treatments be stopped. In addition, they often mentioned that it is the Romanian state’s duty to protect its citizens abroad and to take diplomatic and political actions. For example, this is well reflected in the speeches about the physical and sexual violence to which the Romanian women were subjected their workplaces in Italy. At the same time, the MPs did not rank the discriminatory practices according to a perceived degree of severity; they condemned acts of discrimination equally. The MPs focused both on the ways in which Romanians abroad are discriminated against and on the process of raising awareness about how these practices can be stopped.

Speech content was not influenced by particular events that occurred in Romania. The MPs continuously portrayed discrimination as one of the biggest challenges faced by Romanians abroad. However, the frequency of speeches was higher around external events that affected Romanians abroad. For example, most of the speeches that portrayed the discrimination against Romanians in the UK occurred after the liberalization of the British labor market and after the lifting of restrictions for Romanians in January 2014. Similarly, when Brexit was brought into discussion for the first time, Romanian MPs discussed more frequently how this event could exacerbate the discriminatory treatment of Romanians abroad.

Explaining Discrimination in Parliamentary Speeches

Our analysis started from the assumption that meaningful social action requires an inquiry into the way actors describe and interpret their actions. The qualitative analysis allowed us to identify (1) who speaks about the discrimination of conationals abroad and (2) how discrimination is approached by parliamentarians. In terms of who speaks, we can observe that the MPs who were elected for diaspora delivered one-third of the speeches addressing issues of discrimination in two out of their three terms in office. This reflects both a relatively high degree of descriptive representation and an extensive concern about this topic from other parliamentarians who did not represent the diaspora directly. No relevant partisan differences have been identified. This consensual engagement echoes the Romanian state’s strategy to foster political, economic, and cultural ties with the different Romanian communities abroad, and to recognize migrant communities as part of the national community entitled to special services and support (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014).

The way in which speeches about discrimination are delivered changes according to the community of reference (Figure 1), forming our expectations. Discrimination against migrants is approached mainly from a utilitarian perspective; the denunciation of discrimination can be seen as part of an extraterritorial constituency service. The MPs’ engagement is less an issue of ideology or partisanship and more a strategic opportunity to both talk about a relevant constituency and serve as a link between the nonresident citizens and the state. This activity can be included in the category of utilitarian explanations, suggesting that MPs refer to the transnational constituency service not only to perform their duties but also to gain credibility and, therefore, potential support for future domestic or international agendas. In doing so, the MPs’ speeches refer to the principles of equality and nondiscrimination as part of the foundations of a legal framework for standard civil rights. Engagement with the community of nonresidents does not correspond to a long-distance form of ethnic nationalism. The Romanian MPs reinforce the solidity of their civil rights–focused arguments with references to diffused attitudinal dislike. Our first expectations are therefore confirmed, with a relevant caveat. The thematic analysis shows that MPs invest in a civic form of nationalism. The denunciation of the register of discrimination faced by Romanian citizens echoes references to a community of equal EU citizens, rights-bearing individuals united in their rights and confident in European standards of justice. More specifically, the discrimination is often portrayed as a form of Romanophobia, a subform of xenophobia that has negative connotations – in terms of dislike, distrust, and even violence – with respect to individuals and groups belonging to the community of Romanian migrants.

Figure 1. How Discrimination Is Addressed by Romanian Parliamentarians in Speeches.

This form of xenophobia implies daily life disadvantages on the labor market as well as forms of physical, psychological, and sexual discrimination, which MPs often mention. The rationale behind this diffused negative connotation is generally ascribed to utility-maximization strategies enacted by parties and political entrepreneurs in the country of residence. The explanations provided refer also to strategic media attention that allows discriminatory practices and policies to reach wider audiences. The visibility of news based on the negative portrayal of Romanians is connected to a supportive reaction from media outlets in the country of residence. In the 2008–2016 period, references to the application of EU norms are an opportunity to criticize the misbehavior of other MPs and to ask for a coherent regional/European system in the area of civil rights and rule of law. In 2016–2020, the references to European values leave space for more direct activism, reinforced by traditional diplomatic support together with efficient capacity-building policies and political engagement.

Discrimination against the historic communities is predominantly presented from an identity-focused perspective, as expected. The MPs behave like active protectors of minorities beyond their territorial jurisdiction, by monitoring their conditions and protecting their rights on the basis of coethnic bounds. The MPs justify speaking out against discrimination on the basis of their belonging to the particular community, a nationally defined “us.” The key concept is the presence of minorities at risk of assimilation and discrimination. MPs present themselves as informal ambassadors of communities abroad. The level of sophistication of the argumentation is lower than for migrants. Discrimination is regularly equated to assimilation attempts. Without partisan differences, the MPs’ statements express the need to assist these communities in the preservation of their spiritual, linguistic, and cultural identity.

The denunciation of discriminatory policies and practices is accompanied by references to increased investments in capacity-building policies and programs. MPs legitimize their involvement by virtue of international standards but also as a historical right. The competing jurisdictional claims over the historical communities remain located within a strategy that is conflict neutral. In line with earlier findings (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014, Reference Waterbury2018), the MPs’ discourses correspond to a shared endeavor to support the cultural and linguistic reproduction of historical communities through the symbolic recognition of a cultural/ethnic transborder relationship. Without directly threatening the territorial sovereignty of the countries of residence, MPs exert explicit pressure on the political environment of neighboring states, especially non-EU members. The reference to EU or international norms is used as a rational/legal argument that complements the historical type of representation in their speeches.

Conclusions

The article analyzes the ways in which Romanian parliamentarians address discrimination against communities abroad. The analysis builds on the rich literature available on the relations between the Romanian state and communities abroad (Dumbravă Reference Dumbravă2014; Knott Reference Knott2017b; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2014). The results indicate that Romanian MPs have adopted the role of formal representatives for migrants and informal representatives of historical kin communities. The postcommunist Romanian state resembles a Janus bifront: one face looks like a kin-state that promotes a preferential relationship – with a strong nationalist twist – with coethnic communities; the other looks like a migrant-sending country that relies on European standards of justice. This is consistent across the three terms in office covered by our study.

These findings are important both for the scientific community and for policy makers beyond the single case study investigated here. Consistent with findings from previous studies (Délano and Gamlen Reference Délano and Gamlen2014; Burgess Reference Burgess2020), MPs define and justify their engagement in supporting these communities as part of the broader governable population. Legislative speeches enable them to reach out to these communities by taking a position on their needs and potentially claiming credit for resolving them. They manage this responsibility with different types of justifications, which occasionally overlap. This engagement may have additional political ramifications in terms of empowerment of these communities in the countries of residence. Consequently, policy makers working in the area of citizen engagement, identity formation or preservation, or representation of particular ethnic minority groups can learn several important lessons.

Beyond these empirical insights, the research contributes to the strand of literature interested in how the states of birth or ancestral origin engage with their communities from abroad (Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014; Koinova Reference Koinova2018b; Waterbury Reference Waterbury2018). The focus on the parliamentary level identifies diffused solidarity with these communities, as well as a space for increased accountability and constituency services. It confirms the need to bring into dialogue the literature focused on historical kin communities and migrants in depicting a broader picture of the way origin states create, implement, and discuss transnational practices (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2010).

Further research can substantiate and nuance these findings. One avenue for further study might use as a point of departure the emphasis on discrimination that is prevalent among MPs belonging to most political parties represented in the legislature – across the political spectrum. This transpartisan engagement with different types of communities abroad deserves closer investigation, and future studies could examine why MPs from different parties address issues of coethnics abroad. Alternatively, a future analysis could focus on the speeches oriented toward emigrants, which could compare the situation in Romania to that of other East European countries with large shares of emigrants (for example, Bulgaria, Poland). Another avenue for further research may focus on explaining why politicians opt for a particular framing in their discourse of the discrimination against conationals abroad. This can be achieved with the help of semistructured interviews with the politicians, and it would identify the ways in which the parliamentarians create a bond between themselves and those they intend to represent outside their country’s territory.

Disclosures

None.

Appendix 1: The List of Parliamentary Speeches Used in the Analysis

Note: PDL = Liberal Democratic Party; UDTTMR = The Democratic Union of Tatar Turkish Muslims of Romania; PSD = Social Democratic Party; PRPE = Roma’s Party “Pro Europa”; PNL = National Liberal Party; PP-DD = People’s Party Dan Diaconescu; UNPR = National Union for the Progress of Romania; PC = Conservative Party; PMP = People’s Movement Party; USR = Save Romania Union.

Appendix 2: Word Clouds for the Legislative Speeches per Term in Office 2008–2012