Introduction

While religious communities in Belarus have been visible social actors over the last 30 years, they had never been actively involved in political protests since the end of the Soviet Union. That changed in 2020. During the mass protests before and after the presidential election in August, several of the country’s high-ranking religious representatives publicly took a critical stance against Lukashenka, and believers participated openly in the protests. Additionally, high-ranking leaders of the opposition actively engaged religious rhetoric in order to underline their ethical righteousness in opposing the regime. This development raises questions about the social role of religion and the dynamics within the major religious communities in Belarus.

Although most people in Belarus identify with either the Belarusian Orthodox Church (BOC) or the Roman Catholic Church, the country is considered one of the most secularized countries in the post-Soviet space. The often-described de-secularization (Berger Reference Berger and Berger1999; Karpov Reference Karpov2010), i.e., the return of religion as an influential factor in the public sphere, has a specific dynamic in countries that were formerly subject to state-imposed atheism. In Belarus, trust in the churches and the number of people who identify with religion are rather high. Religious figures frequently appear at official state occasions; religious practices are present in the public space; and the discourse around particular issues of identity, values, and social politics embraces religious rhetoric. At the same time, individual religiosity is low, a majority of the population does not care about the teaching of religious authorities in their private or social lives, and the real influence of religious actors on political decision-making remains hard to quantify. Indeed, the role of religious communities in social and political processes is often difficult to grasp, and the religious component of the mass protests against electoral fraud and state violence is a case in point.

This article analyzes the dynamics of the two main churches’ relation to civil protests on the basis of recent survey data and media monitoring. In December 2020, the Centre for East European and International Studies ZOiS (Germany) conducted an online survey among 2,000 persons living in cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants and aged between 16 and 64. Several questions in the questionnaire revolved around people’s expectations of and attitudes toward religion, allowing us to draw conclusions about the role of the churches and religion during the protests. Also in December 2020, members of the Christian Vision group of the Belarusian Coordination Council – the main opposition platform in Belarus under the leadership of Sviatlana Tiksnouskaya (which is organized in different working groups on particular issues) – conducted an online survey of more than 4,000 members of religious communities, mainly in cities, via the messenger app Viber. Although this survey is not representative due to various methodological limitations, the responses provide important insights into the dynamics among believers and their attitudes toward the protests and the official position of their own religious community.

These empirical insights are combined with an analysis of the activities of different religious representatives in the context of the churches’ respective theological frameworks. After sketching out the religious situation in Belarus and the theological and ecclesial background of the two main churches, I will reconstruct the attitudes and activities of the churches in the political and social realm before and after the 2020 protests. Special attention will be paid to the aspects of religious affiliation of the protesters, different layers of the churches, trust, and social media.

Elaborating on the survey results and media monitoring, the new findings on the role of the churches and religious paradigms in current developments in Belarus offer important insights into the impact of religion in Belarusian political and social processes. Most importantly, the degree of religious communities’ reaction to electoral fraud, mass protests, and state repression depends not so much on their loyalty to, and entanglement with, state power – as often concluded at least for the case of Orthodox churches in Eastern Europe. The analysis shows that the inner fragmentation of the churches and the power of social media networking diminish the effect of political strategy. Although the BOC appears to be a mere pillar of authoritarian state power and ignores the calls for solidarity of people within and outside the church, theological arguments, faith-based notions of solidarity, and the experience of individual resilience under conditions of persecution strengthen the religious factor in Belarusian civil society.

Preconditions for Religious Participation in the Belarusian Protests

Religious Situation in Post-Soviet Belarus

Belarus is one of the most secular societies of the former Soviet Union (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich, Bulhakau and Lastouski2015, 100). The process of forced secularization by the Soviet regime and the complex circumstances surrounding the return of religion to the public sphere and private life after the end of the Soviet Union have been presented in detail for the case of Belarus by Nelly Bekus (Reference Bekus, Wawrzonek, Bekus-Gonczarowa and Korzeniewska-Wiszniewska2016, 72–82). However, despite this legacy and the outspoken secular policy of the government, numbers of religious identification are rather high. Similar to other post-Soviet countries, identification with the Orthodox Church is particularly high in Belarus, with approximately 70–75% of the population describing themselves as Orthodox. The second largest religious community is the Roman Catholic Church, which accounts for about 12–15% of the population. Smaller communities include various Evangelical and Protestant groups,Footnote 1 as well as Jewish and Islamic minorities. This distribution is also reflected in the number of registered religious communities. At the beginning of 2021, there were 1,714 registered BOC congregations, 499 Roman Catholic congregations, 1,005 Protestant congregations, 16 Greek Catholic congregations, 51 Jewish congregations, and 24 Muslim congregations (Upolnomochennyy 2021).

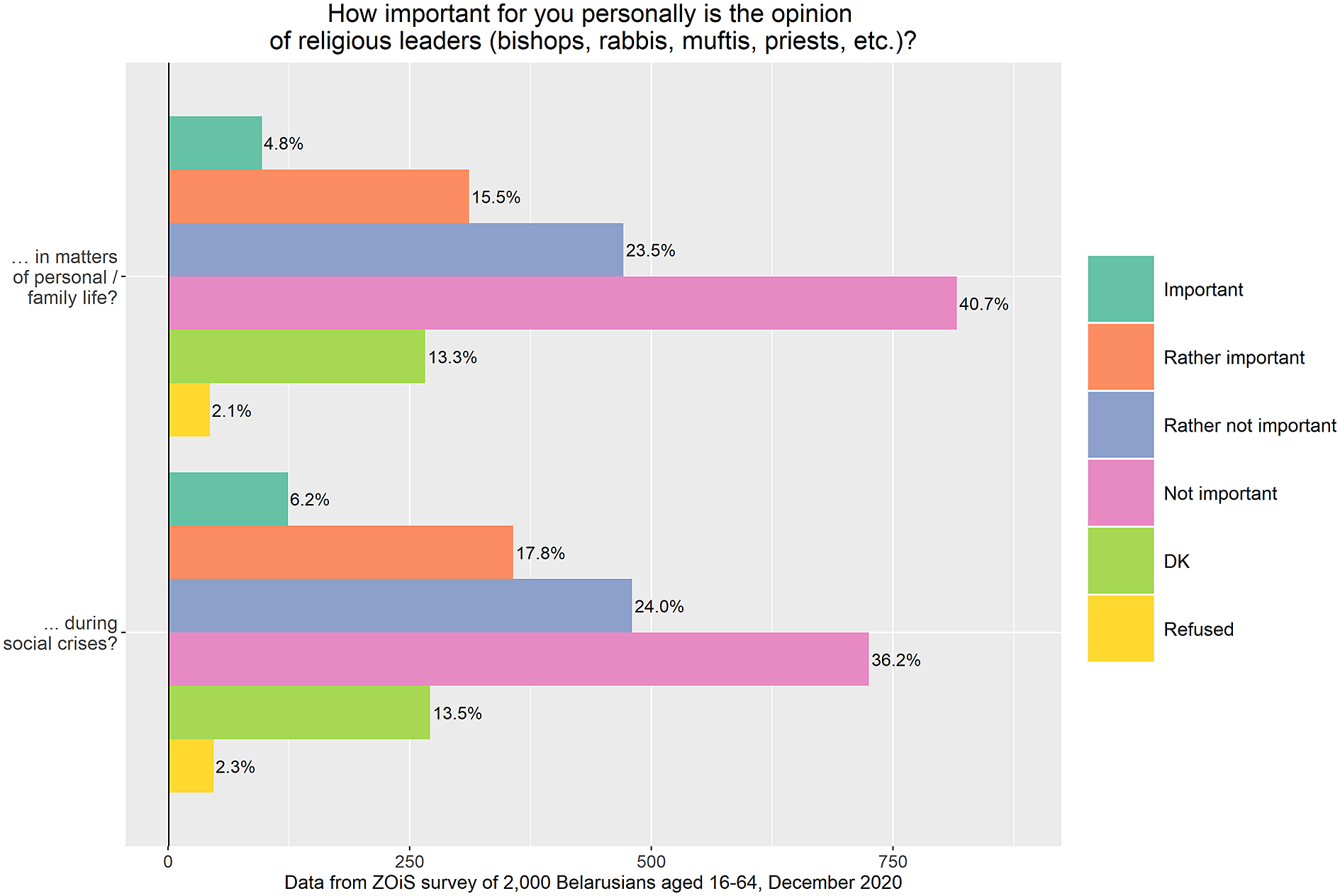

The strong identification with the Orthodox Church does not translate into a correspondingly high level of personal religiosity. The results of recent surveys conducted by ZOiS show that only a small percentage of the population prays regularly or attends a place of worship (Figure 1). The church leadership’s positions also play a rather minor role in matters of private or social life. The strong religious identification thus corresponds largely to a cultural identification, a phenomenon that can also be observed in Russia (Pew 2017). As a result, religious affiliations may be mobilized less through religious content than through issues of cultural identity. This link between religious and cultural identification also makes the political use of religious markers attractive. As Bekus writes, “the president of Belarus found the Orthodox religious tradition useful and transformed it into an instrument of historical and cultural justification for his political strategy” (Reference Bekus, Wawrzonek, Bekus-Gonczarowa and Korzeniewska-Wiszniewska2016, 141). However, as “no religious denomination has had strong, if any, connection to Belarusian national idea” (Ioffe Reference Ioffe2020), it can be difficult to mobilize religious communities for any kind of national identity strategy, especially compared to neighboring Russia, Ukraine, or Poland. Thus, the PEW survey shows Belarus as least committed to questions of national identity among all Orthodox countries in Eastern Europe (PEW 2017, 148ff).

Figure 1. “How important for you personally is the opinion of religious leaders (bishops, rabbis, muftis, priests, etc.)?” Data from ZOiS survey of 2000 Bearusians aged 16-64, December 2020.

Both the Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church have a specific influence on public discourse in Belarus. Their presence is particularly felt in the discourse on conservative values, and they actively cooperate in this sphere despite enormous ecumenical reservations. Here, too, the situation is similar to other post-Soviet countries such as Russia or Ukraine, where churches and religious communities cooperate closely on value issues such as combating abortion, supporting traditional gender roles, and opposing sexual education in schools, although a convergence at the dogmatic level is explicitly ruled out (Shishkov Reference Shishkov2017). Since the conservative values of the churches correspond to the patriarchal principles of authoritarian governance, the interests of the state and the churches are very close on the values agenda, and relevant measures are supported by both sides in each case.

The connection of the two major religious communities to their respective church families abroad – the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) on the one hand and the Catholic Church in Poland and the Vatican on the other – is another important aspect of the religious situation in Belarus. This transnational linkage makes the churches fundamentally less prone to national appropriations (Bekus Reference Bekus, Wawrzonek, Bekus-Gonczarowa and Korzeniewska-Wiszniewska2016, 172ff.), but at the same time it makes them more likely to A) come under suspicion for allegedly representing foreign interests and B) be exposed to corresponding sanctions. For example, the Catholic Church has struggled for a long time with arbitrary entry restrictions on several of its priests, monastics, and pastoral workers from Poland. For the Belarusian Orthodox Church (BOC), this danger was long considered irrelevant, despite the fact that Metropolitan Filaret (Vakhromeev) and Metropolitan Pavel (Ponomariov) were Russian citizens. Since the BOC, as part of the Russian Orthodox Church, symbolized the common civilizational project of the “Russian world,” it represented no threat. However, events in the summer of 2020, when the then head of the church, Metropolitan Pavel, had to leave the country, showed that the BOC is not immune from state encroachment. It seems likely that Pavel’s Russian citizenship became an excuse to exert pressure on the church after he took a slightly critical stance against the police crackdown.

Protest and the Churches: Socio-Ethical Points of Departure

The protests after the rigged election in August 2020 were not the first political protests in Belarus since the end of the Soviet Union. To understand the significance of the religious factor, it can be helpful to look at the attitudes of the largest religious communities during previous protests after the 2006, 2010, and 2015 elections and against further rapprochement with Russia in 2019. Remarkably, in all of these protests, there is no evidence of a particular, publicly visible faith-based participation. The reasons for the reluctance of the two largest religious communities in Belarus to participate in these sociopolitical processes are different for the Orthodox and the Catholic Churches.

The global Catholic Church has a tradition of resisting social injustice and political repression, which was put on a firm theological footing in the 20th century after the experience of Fascism in Catholic countries and its reappraisal by, among others, the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). During the Cold War, a certain differentiation became apparent in this confrontation with state-sponsored injustice. While the Vatican was wary of the theological justification of resistance in the South American and African contexts by Liberation Theology, resistance to communism in Eastern Europe was supported as preservation of the faith. The critical distance to state power in those cases when it openly contradicted Christian values and traditions became particularly important for Catholic theology during this period.

The example of the Catholic Church in Poland and the civil power it wielded under authoritarian rule had a dual symbolism, especially for Eastern Europe: On the one hand, for the external world, it demonstrated the mobilizing potential of the churches in sociopolitical crises. On the other hand, and more inwardly, it also made it clear that social protest aimed at freedom from state repression does not necessarily imply a liberal attitude to questions of personal freedom and ecclesiastical tradition.

In Belarus, this legacy is particularly relevant for the Catholic Church, which is strongly influenced by Polish catholicity. It is a religious minority heavily engaged in pastoral and social activities, and a large part of the clergy and pastoral workers come from Poland or studied there (In 2002, out of 274 Catholic priests, 150 were Polish citizens (Danilov Reference Danilov2004); by 2007, out of 470 Catholic priests, 181 were Polish citizens; by 2009, 161; by 2015, 113 were Polish citizens; and by 2019, 87 were Polish citizens (Ioffe Reference Ioffe2020). This is why the church has for many years been identified with foreign interests, and as such has been the object of state arbitrariness at least since the limitation on religious freedom after 2002, when a new law on religious organizations was introduced (Hill Reference Hill2002; see also Lastouski Reference Lastouski and Zakharov2022). Polish priests and pastoral workers have repeatedly been prevented from entering or returning to Belarus from Poland (Smok Reference Smok2015). With the appointment of Archbishop Tadevush Kandrusyevich as head of the Minsk-Mogilev Metropolis in 2007, the relationship changed slightly (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich, Pankovsky and Kostyugova2009, 164). Kandrusyevich brought experience of cooperating with the Orthodox Church through his work in Russia and, as a Belarusian citizen, was less suspected of Polish influence. He was, moreover, motivated to actively involve himself and the Catholic Church in social debates and supportive of Lukashenka’s course toward European rapprochement at the time.

However, the Catholic Church’s social engagement was strictly limited to issues of morality and humanitarian work, as political inquiries could be interpreted as interference and sanctioned accordingly. As the annual reports on the state of the religious sphere in the Belarusian Yearbook (Pankovski and Kostyugova 2003-Reference Pankovski and Valeria2021) show, the Belarusian leadership strategically tailored its approach to the Catholic Church in the context of elections, without ever stipulating concrete concessions (e.g., concordat, religious education in schools, legal restriction of abortion, relaxation of religious legislation, etc.). The Catholic Church’s current potential to take a critical stance on important sociopolitical issues is massively limited by the regime’s legislative arbitrariness and the manipulative use of religious policy. On those occasions when the Catholic Church has expressed critical views, it has mainly been in response to restrictions on its own pastoral activities or in relation to moral-theological issues such as the death penalty and legal regulations that endanger the traditional image of the family (e.g., reproductive medicine, domestic violence). A noteworthy exception was the protest in 2019 by the church leadership and many believers at the Kuropaty memorial site near Kyiv, where the state ordered to remove crosses remembering the victims of Stalin’s terror against believers (Kandrusyevich Reference Kandrusyevich2019). However, the church has never taken a position on the political protests.

The Belarusian Orthodox Church (BOC) has a different legal status to all other religious communities in the country. When Alexander Lukashenka took office in 1994 and made the first adjustments to the constitution in 1996 and the laws on freedom of religion and conscience in 2002, the BOC was given a privileged position as “particularly important for the historical development of Belarusian cultural tradition” (Bekus Reference Bekus, Wawrzonek, Bekus-Gonczarowa and Korzeniewska-Wiszniewska2016). The systematic political capture of Orthodoxy in the years of Lukashenka’s presidency made a critical stance of the BOC unlikely, while the degree of privilege corresponds to Orthodoxy’s self-image as a pillar of civilizational identity in Belarus. In addition, the paradigm of a critical distance to the state, which had been theologically strengthened in Western ecclesiastical traditions by the experiences of the 20th century, is alien to the Orthodox tradition and has found its echo only selectively and often in conflict with mainstream orthodox institutions.

The historical roots of this lie in the consolidation of the symphonia principle, according to which church and state cooperate closely for the good of the people (Antonov Reference Antonov2020; Demacopoulos and Papanikolaou Reference Demacopoulos and Papanikolaou2016; Perabo Reference Perabo2018). In history, this principle always meant that the church subordinated itself to a certain degree to the secular ruler and recognized him as the ruler appointed by God, even if he restricted or persecuted the church. It was not until 2000 that the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) formulated a right of resistance for the first time and as the first Orthodox church in its “Basis of the Social Conception.” At the same time, the ROC insists that even in the case of persecution by the state, the church shall remain loyal to the state (Social Concept III.5). The church recognizes prayer, appeals, dialogue with those in power, and pastoral accompaniment of politicians who profess the Orthodox faith as instruments for criticizing the state, but not public protest.

The BOC forms part of the ROC (as a so-called exarchate with limited autonomy) and both churches share the same doctrine, liturgical tradition, historical roots, and cultural identity, as well as the same social concept. Accordingly, when it comes to relations with the state, all the concepts enshrined in official ROC documents also apply to the BOC: the separation of church and state tied to loyalty to the current rulers; the ambivalent acceptance of democracy; the acknowledgement of a minimal right to resist while rejecting any political protests that threaten the government; and the primacy of state stability and unity.

In addition, in both countries, the Orthodox Churches theologically legitimize so-called spiritual-moral values and are engaged in their strategic implementation in legislation, education, and the military. In the case of Belarus, the church cooperates with the Ministry of Education, which emphasizes the importance of traditional Christian moral values for Belarusian statehood (Church.by 2015), with the armed forces to enable “spiritual, moral and patriotic education of military personnel” (Ministerstvo Reference Ministerstvo Oborony2004), and it is a prominent actor in the pro-life discourse (www.pro-life.by). The church understands this cooperation with state structures as the direct implementation of its mission to serve the people (Filaret 2012).

It is apparent from this brief sketch that for the BOC leadership, the path to societal improvement always goes through state structures and there is hardly any room for civil society activities – including protest. The description of the “sinful and spiritually harmful actions” (SC III.5) that would justify civil resistance remains vague. In fact, Orthodox theology lacks a social ethics that could provide a more concrete definition beyond individual faith practice and sinfulness. Thus, in the case of the state repressions in Belarus, it remains open whether rigged elections, the state order of police violence, inhumane prison conditions, state surveillance, and the restriction of freedom of speech and freedom of the press can be assessed as “sinful and spiritually harmful” beyond the personal responsibility of each individual affected.

In accordance with these theological aspects, in all previous protests, the BOC either adopted an explicitly neutral stance or assured the state of its loyalty. Official church representatives generally ignored the protests around elections. Overall, civil protest in the form of demonstrations and other public actions appears to be contrary to the church’s teachings, unlike personal meetings and lobbying in the form of submissions on proposed legislation and cooperation agreements between state bodies and church representatives. This situation reflects the concept of the church as a hierarchical system where only the ordained leadership is authorized to act in the name of the institution.

The underdevelopment of religious actors as civil society actors described by Natallia Vasilevich in Reference Vasilevich, Bulhakau and Lastouski2015 (126) has led to an increasing withdrawal of the institutionalized churches from sociopolitical debates. However, this institutional retreat should not obscure the fact that the faithful nevertheless participate actively in civil society. In addition to the various movements for traditional family values, often organized at the level of parishes, brother- and sisterhoods (Mudrov/Sakharov Reference Mudrov and Zakharov2021), and in some cases ecumenically, a Belarus Christian Democracy party and an associated youth organization have existed since 2005. One remarkable example are the protests by believers against state control (and de facto destruction) of the Kurapaty memorial in 2019 (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich2019). These events, where believers came out in public to protest and withstand the deconstruction of a landmark memorial to the victims of Stalinist terror, testify to the will of believers to express their position critically and publicly.

The leaderships of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches have repeatedly tried to control or distance themselves from grassroots activities. In the case of priests, this is done through administrative measures (transfers, suspension from active pastoral ministry). In the case of laypeople, the Catholic Church banned the use of “Catholic” in 2009 in all cases where the activities are not previously agreed upon with a clergyman (Catholic.by 2009); the BOC already had its name legally protected in 2003 (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich, Bulhakau and Lastouski2015, 118). Another instrument of control is the blessing that laypeople must obtain from the clergy for public activities. The ROC issued a corresponding official directive in 2011, which is also valid for the territory of the BOC (Arkhiereiskij Sobor 2011). These church policies have had two consequences: First, the faith-based activities of believers who want to express faith-based resistance to state repression have been increasingly made invisible within the church. And second, the visible activities within the church are becoming homogenized, with the result that it is perceived as a unified, politically loyal organism. Both aspects played an important role in the 2020 protests.

The Churches and the 2020 Protests

The protests in Belarus before and especially after the 2020 presidential election strongly influenced the major religious communities and at the same time had a religious component in protest symbols and messages of opposition leaders. Although the results of various surveys initially suggest that religious identity played a rather subordinate role during the protest, a more detailed analysis of activities and moods within the churches turns to a more complex picture because it shows that protestors may have different reasons to identify – or not – with the church as an institution and to do so in a public survey.

Religious Affiliation Among Protest Participants

The religious identity of the protesters roughly corresponds to the distribution in the population as a whole. The results of a survey conducted by the MOBILISE project reveal that 55% of participants identify as Orthodox, about 7% as Catholic, and 30% as non-religious or atheist (Onuch Reference Onuch2021). The number of those who identify as non-religious is 30%, significantly higher than the population average (about 20% according to the World Values Survey and the ZOiS Survey). This confirms the development described above, whereby mobilization on sociopolitical issues by the institutionalized religious communities in Belarus has slowed down. The ZOiS survey in Belarus in December 2020 showed that, in particular, identification with the Orthodox Church makes participation in protests less likely and support for authoritarian forms of government more likely (Douglas et al. Reference Douglas2021).

Olga Onuch contrasts the religious affiliation among the protesters in Belarus with the Maidan protests in Ukraine, where the proportion of religious people was particularly high (Onuch Reference Onuch2021). There are several reasons for that difference. First, for Ukraine, the distinct pro-European sentiments among believers in the Christian churches played a mobilizing role in the context of the pro-European agenda of the protests (Buchholz Reference Buchholz2016). Religious identification in Ukraine is particularly high among believers in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), which traditionally strives for greater openness toward Europe and was particularly vocal in its support for the Maidan protests (Avvakumov Reference Avvakumov, Krawchuk and Bremer2016). The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate took a similar position. Accordingly, both churches were particularly active on the Maidan and in mobilizing for its causes. Second, the fact that the Ukrainian churches are not subject to such massive political capture as the churches in Belarus, and the faithful thus enjoy greater freedom to position themselves in sociopolitical matters, is also an important factor. Underpinned by a solid social ethics, the UGCC was particularly well prepared to take a public stance. The third factor is religious plurality, which plays a decisive role because it promotes competition in questions of public visibility and attitudes toward the common good. The churches and believers can avoid this competitive situation only at the risk of losing their social relevance.

None of these three factors are applicable to Belarus. For the post-Soviet context, the active and publicly visible participation of believers in the protests against authoritarian rule is unprecedented. The impulse to compare the situation in Belarus with the Euromaidan in Ukraine is natural yet controversial, as the religious politics and landscapes of the two countries differ considerably. If anything, the attitudes of the Russian churches offer a better basis for comparison, as the degree of state control of the religious institutions and the strict centralized, partly repressive structure within the churches is broadly similar across these two countries.

The processes of demarcation between the concurring churches and between the European and Russian civilizational projects, which had mobilized the Ukrainian churches so massively for the Maidan, played no role in the protests in Belarus. Despite obvious violations and violent suppression of protests, Lukashenka’s regime could always count on the loyalty of the churches in previous elections. Even the massive human rights violations – well known for many years – had never led to visible protest or solidarity with the victims by the churches. Finally, since the surveys were conducted after Lukashenka’s warning to the churches not to become involved in the protests (Lukashenka Reference Lukashenka2020) and against the background of the BOC’s call for neutrality and growing internal pressure on the clergy and believers, it is no surprise that a high percentage of protesters did not – or no longer wanted to – identify with the church and its unwillingness to criticize the regime.

However, half of the protesters did identify as Orthodox. This group warrants further research, since identifying as Orthodox means obviously different things to different people. Some people make no connection between their religious affiliation and their participation in the protests, and the hierarchy’s warnings not to participate are therefore irrelevant for them. Given the high percentage of people identifying with religion on a rather cultural, non-religious level, the mobilization against the direct prohibition of religious symbols, attacks on church buildings, and violation of fundamental values seems at least surprising. It supports, still, the thesis that the religious factor in Belarus is more difficult to mobilize in issues of national interest in the regime’s interpretation. It further points to the fact that the awareness of religious values in the civil society is much higher than surveys about the impact of the churches’ hierarchy suggest. Others view their participation as a deliberate act of defiance vis-à-vis the official position in accordance with the conviction that the values behind the protests reflect true Christian values. This complex situation points to the necessity of distinguishing between the different layers of the church and looking at the protest behaviors that derive from that.

Official Position of the Churches on the 2020 Protests

The 2020 presidential election was accompanied by critical voices from the churches. Social media played an important role in this regard, with Facebook and Telegram disseminating not only appeals against electoral fraud by Catholic and Orthodox believers and priests but also the official statements by the church leadership.

On July 31, Archbishop Kandrusyevich issued a first statement on the upcoming election (Kandrusyevich Reference Kandrusyevich2020), calling for participation and urging people to be guided by the extent to which the candidates represent the church’s moral (family as a covenant of man and woman to procreate children; protection of life from conception to death) and socio-ethical (religious freedom, social justice) principles. Kandrusyevich referred to the social tensions in the country and called for the preservation of stability and unity.

In three subsequent statements (Catholic.by 2020; Kandrusyevich Reference Kandrusyevich2020a; Catholic.by 2020a; Kandrusyevich Reference Kandrusyevich2020b), Kandrusyevich and the Bishop’s Conference called on Belarusian Catholics to pray the rosary for Belarus, demanded non-violence, lamented the victims on both sides, and called for the establishment of a round table to resolve the conflict. The bishops directly addressed Lukashenka and the ruling elites, clearly positioning the Catholic Church on the side of the protesters “who took part in peaceful demonstrations and who want to know the truth” (Catholic.by 2020a) and against the excessive violent actions of the state: “shedding blood on the streets of our cities, beating people […] cruel treatment of them and keeping them in inhuman conditions in places of detention is a grave sin on the conscience of those who give criminal orders and commit violence” (Catholic.by 2020a). In addition, many churches kept their doors open day and night to provide a possible refuge from violence, and prayers for peace in the country were called for in all congregations.

Remarkably, the Vatican did not actively endorse this critical position of the Roman Catholic Church. Pope Francis only tentatively voiced his support in prayers, while the Vatican diplomats in Belarus – the newly appointed nuncio Ante Jozic, the Vatican Secretary for Relations with States, Richard Gallagher, and the special envoy Claudio Gugerotti – made an appearance with the political leadership of the country. When Kandrusyevich was denied access to Belarus after a trip to Poland in August 2020, Belarusian Catholics tried to rally international support for him, but to no avail. He was allowed to return only after three months, in what was publicly propagated as a kindness of Lukashenka to the pope, who immediately accepted the archbishop’s resignation on January 3, 2021. Since then, no further official critique in relation to the regime and its ongoing crackdown on Belarusian citizens was voiced.

The leadership of the BOC reacted to the electoral fraud and the subsequent protests in a much more reserved manner. Metropolitan Pavel (Ponomariov) and Honorary Exarch Filaret (Vakhromeev) issued messages (Filaret 2020; Pavel 2020) on the day of the election calling on people to take responsibility for the country’s future and urgently warning against possible violence and provocations. After the elections, the Patriarch of Moscow, Kirill, and Metropolitan Pavel were among the first to publish their congratulations to Lukashenka on August 10, causing a storm of indignation among believers and nonbelievers. In the days that followed, official pronouncements maintained the rhetoric of neutrality and avoided taking sides.

The ambivalent stance of the leadership was reflected by diverging statements on the meso-level of the church. Official voices like the Archbishop of Hrodno, Artsyemi, the spokesperson of the Exarchate, Siharei Lepin, and the priest Alexander Kukhta, which openly criticized the violence and repression or, on the other hand, unanimously supported the regime, and the actions of the security bodies such as the head of the Holy-Elizabeth monastery, Andrey Lemeshonok, gained wide public attention. As a reaction, the church leadership distanced itself from all grassroots initiatives (Church.by 2020). Bishops warned their priests and faithful not to participate in protests as expressions of “emotions” and “unforgiven offences” (Gurij 2020) and to use Christian symbols (prayer, bible, hymns) as a tool in political struggle. The only means appropriate to Orthodox believers in such a heated atmosphere should be prayer and fasting. The most critical voices on the official level were removed from their positions (Monitoring 2021).

Despite the efforts of the BOC’s leadership to produce a homogenous, neutral voice of the church, the breadth of the public statements shows a noteworthy heterogeneity of positions within the Orthodox Church: such a clearly visible fragmentation of the church on political issues has never been seen before. This fragmentation is confirmed by the surveys among believers conducted by the Coordination Council’s Christian Vision working group in December 2020. Asked, among other things, about the church leadership’s position, believers’ approval turns out to be particularly low among Orthodox participants (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich2021). Frustration and disappointment, as well as the desire to change one’s denomination dominate among Orthodox believers in the survey. Remarkably, the respondents are less dissatisfied with specific actions on the part of the church leadership than with the lack of a clear stance against state violence. This points to the believer’s awareness about the differentiation between Christian values and socio-ethical principles on the one side, and institutional obligations on the other.

Trust in the Churches

The ambivalent attitude of the BOC church leadership had a direct effect on institutional trust. The ZOiS survey shows that in December 2020, about 40% of respondents trusted the Orthodox Church fully or partly; in the second wave of the survey in summer 2021 this number decreased to 34%.Footnote 2 Although the Orthodox Church is still one of the social institutions with a comparatively high level of trust, these figures indicate a sharp decline from the level of around 60% that the BOC had enjoyed over the years.

It can be assumed that trust in the BOC had already declined by the beginning of 2020 due to its refusal to take measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic (Shramko Reference Shramko, Anatoly and Valeria2021). At the same time, the high level of institutional trust in the BOC resulted from its emphatically neutral position in all political conflicts and the perception that, as a transcendent organization, it remained independent in all secular conflicts. However, it was this very neutrality, which had hitherto carried the church through all socio-political crises since the end of the Soviet Union, that was massively called into question in the summer of 2020. As the Chatham House survey shows, half of the respondents agreed fully or somewhat with the statement “I believe that it’s currently impossible to remain neutral” (23.8% fully agree, 22.7% somewhat agree, 26.7% unsure, 16.5% mostly disagree, 10.2% totally disagree; Astapenia Reference Astapenia2020).

From a theological perspective, the question of trust in the church again brings up the issue of people’s understanding of what the church is. An overall level of trust in the church does not differentiate between trust in the church leadership, which is mainly perceived through official statements, and trust in local congregations, which have a significant influence through personal contacts. Nor does it reflect the difference between the church as a transcendent organization on the one hand and in its secular manifestation on the other, which may well play a major role in the perception of the church. Accordingly, the comparatively high level of trust in the churches can be interpreted in different ways: as the success of the church leadership’s strategy of neutrality, or also as trust in the committed priests on the ground.

The massive loss of trust in the Orthodox Church is also reflected in the surveys of the Christian Vision working group: almost 90% of Orthodox respondents say they trust church leaders less after the protests. The concrete activities of individual hierarchs (e.g., congratulations on the “election victory,” official meetings with Lukashenka or in support of him, putting pressure on critical priests and believers) and their failure to adopt a clear position against the violence (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich2021) played a significant role here. By contrast, trust in the Catholic Church has grown until December, which can be assumed to be an endorsement of the clear stance of Catholic priests and bishops. Remarkably, although the Catholic community in Belarus was shaken by the ambivalent position of the Vatican, the lack of visible support from the pope and from the Vatican diplomats had no influence on the commitment of church members to their own local community. These findings suggest that trust in the church is based less on its status as an institution above worldly matters, and more on the committed and credible public actions of church representatives in concrete local communities. The recent data by Chatham accordingly show decreasing trust in the Catholic Church since April 2021, when the hierarchy became silent on the continuous repressions (Astapenia Reference Astapenia2021).

Expectations of the Churches

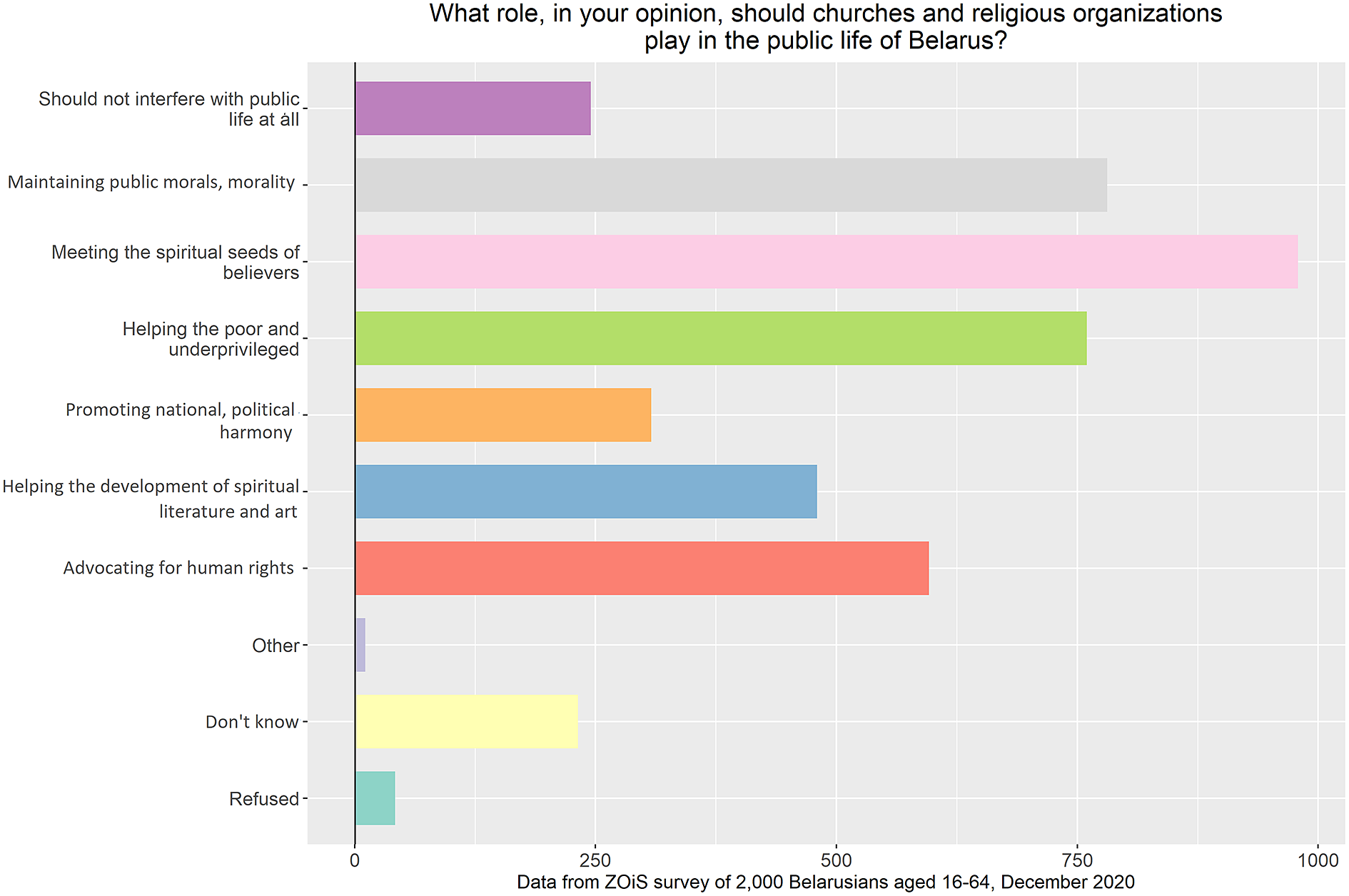

The loss of trust in the Orthodox Church and the disappointment at its behavior suggest that people have high expectations of the churches, despite the prevalence of secular views. This is true both inside and outside the churches themselves – they are credited not only with satisfying the spiritual needs of the faithful but also with supporting public morality, helping the disadvantaged, and advocating human rights (Figure 2). Only a small percentage of respondents believe that the church should completely stay out of public life.

Figure 2. “What role, in your opinion, should churches and religius organizations play in the public life of Belarus?” Data from ZOiS survey of 2000 Belarusians aged 16-64, December 2020.

This expectation clashes with the self-image of the Orthodox Church and coincides with that of the Catholic Church. The Orthodox Church’s position on human rights and questions of the common good does not follow a theological system and depends primarily on the concrete relationship between church and state. In the Russian (and Belarusian) Orthodox Churches, a collectivist understanding of human rights has been propagated over the past 20 years, according to which all individual rights and freedoms must take a back seat to the rights of the community – the state, the fatherland, or the church (Stoeckl Reference Stoeckl, Giordan and Zrinščak2020). Since this understanding is broadly compatible with principles of the communist ideology, it has been met with a certain approval among the population.

However, protests against arbitrary state power in particular show how widespread opposition to such a collectivist position is among the population and within the Orthodox Church. The open letters of Russian priests and believers in support of political prisoners in 2019 and during the Belarusian protests in 2020, the open letters of Belarusian parishes to their church leadership, and the statements of the Christian Vision working group of the Belarusian Coordination Council all testify to a complex understanding of Christian values such as truth, justice, and human dignity. This commitment to common values justifies resistance to a violent political regime, particularly in community with other pro-democratic civil society groups. The expectation that the Orthodox Church should stand unequivocally by these Christian values is also reflected in the responses of believers to the question of how they would like the church leadership to deal with the political crisis (Vasilevich Reference Vasilevich2021): the absolute majority expects a public, truthful assessment of the events, and an unequivocal condemnation of the violence.

This points to a revealing distinction in the understanding of the church’s position in the world (Elsner Reference Elsner2020). While the BOC leadership defines this position mainly through its pastoral accompaniment of the faithful (including politicians) and suspects any sociopolitical statement of being “political,” believers and those distant from the church transfer the principles of Christian ethics to the sphere of social coexistence and expect the church to represent these values publicly, not only in sermons and confession. The declarations of Archbishop Artsyemi of Hrodno, the commitment of priests to the prisoners and the tortured, and the open churches serving as shelters from the security organs correspond to this understanding of Christian values, as do the advocacy against electoral fraud, the protest against torture, and the non-violent walks as a show of solidarity. This convergence of values is vividly illustrated by the public statements of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya addressed to believers (Tsikhanouskaya Reference Tsikhanouskaya2020) and Pope Francis (Tsikhanouskaya Reference Tsikhanouskaya2020a) and by her participation in ecumenical prayers during her visits to Germany and other countries.

Thus, many believers had no qualms about joining or sympathizing with the protests, even if the Orthodox Church leadership insisted on limiting activities to “purely religious” instruments such as prayer. Remarkably, public prayers, which can be understood as a bridge between genuinely religious forms of expression and a public statement, found little support compared to other forms of protest (Elsner Reference Elsner2021). This may be due to reservations about ecumenical activities and the desire to not to be exploited by the institutionalized church. What is more significant, however, is the extent to which many people who describe themselves as Orthodox have become alienated from the religious practices of the churches, perceive prayer exclusively as a private religious act, and are guided in their civil position more by the values of social justice and solidarity than the official recommendations of the church leadership.

Although the churches’ leadership did a lot already before the 2020 protests to move politically active believers out of the church, they show an impressive resilience in maintaining Christian values under repression. While this could be justified, on the one hand, by the experience of resistance during the communist rule, it shows also the effects of believers being a part of an emerging civil society, with whom they share the repressive everyday life. As solidarity becomes a key concept within the protest (Shparaga Reference Weichsel2021), Christians are empowered to join a democratic social forum such as the Coordination Council to put forward their vision of the country’s future together with other social groups. They do so – to date – without any claim to interpretative sovereignty, a special identity-forming or moral role of the churches. Instead, the focus is on fundamental ethical demands for non-violence, justice, freedom and truth, without any political slogans.

The Churches and Social Media

Informal networks and social media became particularly important given the limited opportunities to voice a critical position on the rigged elections and state violence against protesters in public spaces. Several studies have shown the importance of social media during the 2020 protests in Belarus for disseminating information, planning solidarity actions, networking, and increasing the visibility of the violence. As surveys show, the vast majority of the Belarusian population obtains information via social media and distrusts state and traditional print and TV media (Douglas et al. Reference Douglas2021; Herasimenka et al. Reference Herasimenka, Lokot, Onuch and Wijermars2020; Gabowitsch Reference Gabowitsch2021).

For Orthodox believers, social media had become a central instrument of exchange and networking even before 2020. As state repression of the churches was relayed by the church leadership to critical believers and clergy, groups on social networks such as Telegram and Facebook opened up spaces for discussion that had been lacking within the BOC. When pressure on critical voices intensified in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and the start of the election campaign in early 2020, social media activity increased accordingly.

Most significantly, the virtual spiritual communities the faithful established during the pandemic to avoid public on-site liturgy would later serve as a space for the protest-related exchange of information and empowerment. Thus, Orthodox priest Aleksander Kukhta and deacon Dmitrij Pavlyukevich already had a huge audience on YouTube (“Batyushka otvetit”) and Instagram (“Bogoslovie,” “Batyushka otvetit”), where they explained religious feasts and practices in an unconventional way. Following the election, they used these channels to draw attention to the falsification of the election and subsequent repressions. In a similar manner, the Orthodox priest Alexandr Shramko (@popoffside), who was suspended earlier in 2018 due to a critical stance on the political involvement of the church leadership (Breskii and Vasilevich Reference Breskii and Vasilevich2020), used his audience in Telegram to inform about protests and dissenting voices from the church. The catholic priest Vjacheslav Barok (@Barok_Rasony) increased his appearance in Telegram and Youtube after being judged for participating in the protests.

The Christian Vision working group of the Coordination Council established a channel on Telegram on September 24, 2020, which spread news related to religious communities. And as early as July 14, 2020, the platform “belarus2020.churchby.info” started to publish news and analyses at the intersection of religion and political protest, providing immediate visibility for the different positions and actors. The platform editors also publish a monitoring of protest-related persecution of the faithful and translations from and into several foreign languages, thus facilitating international awareness and solidarity, as well as giving the Belarusian audience a broader perspective on the events.

The active use of social media changes the dynamic of protest among believers by increasing the visibility of faith-based critique from priests and bishops and thus encouraging the faithful to support the protests. At the same time, the speed at which news spreads among this highly attentive media public also made the open loyalty of some hierarchs to the repressive state more visible. Statements and sermons in support of Lukashenka and the strategy of the riot police as well as the appearance of priests, nuns and bishops at pro-Lukashenka events were immediately picked up on for a wider debate within the churches.

This mix of fast and accessible information about the heterogeneity of church activities thus fostered a kind of public theology, which is outstanding for the post-Soviet context. It can be compared to the Ukrainian case (Krawchuk and Bremer Reference Krawchuk and Bremer2016; Public Theology after Maidan 2020), yet the scope of comparison is limited by the very different religious landscapes. As Vasilevich (Reference Vasilevich2020) points out, Belarusian public theology developed in the course of the last decade as a reaction to the hierarchy’s failure to adopt a social position. Vasilevich describes the “demoralization and frustration” of the faithful that resulted from the hierarchy’s occupation of the voice of the church over a long period and its refusal to engage with its flock on social questions. Thus, the “Telegram revolution” (Herasimenka Reference Herasimenka, Lokot, Onuch and Wijermars2020) provided new structures and mechanisms for regaining a distinct religious voice in public processes as a counterbalance to the support of the majority of the hierarchy for the regime.

Interestingly, the established media networks became subsequently an important platform of the Belarusian Christian opposition to the religious legitimization of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Since February 2022, the Christian Vision group of the Coordination Council analyses the war-related processes within the churches, some actors like Aleksandr Kukhta participate in support for refugees. This shows the sustainability of the established social networks, and – more relevant – the fundamental socio-ethical commitment of the actors, which goes beyond confessional or national interests.

Conclusion

In June 2021, the leading voice of Orthodox regime critique in Belarus, Archbishop Artsyemi of Hrodno, was removed by the Synod of the ROC in response to a petition from the BOC Synod (Christian Vision Group 2021). The decision symbolizes the end of the already marginal resistance of the BOC leadership to state pressure.

The data and developments within the major Belarusian religious communities examined in this article testify to the complex intersection of religion, society, and state in post-Soviet Belarus. How religious communities react to electoral fraud, mass protests, and state repression depends not on their loyalty to and entanglement of the hierarchy with state power but on the relations between different layers of the church, theological foundations, the impact of foreign institutional structures, and individual and institutional resilience under conditions of persecution. The findings of this analysis contribute significantly to our understanding of the religious component of the 2020 Belarusian protests.

The analyzed data show how crucial the distinction between the different layers of the church is. The protests unfolded a remarkable heterogeneity within the Orthodox Church, including a resistance to the symphonic model of state-church relationship. The highly engaged local Catholic Church, on the other hand, appeared to be weakened by the Vatican diplomacy. Most importantly, when we take a closer look at the different layers of a church, we see highly engaged laypeople and clergy in both churches who have a remarkable impact on the discourse of the democratic opposition and appear to be a rather natural part of civil society.

Given the parallels with the Russian context (rather than with Ukraine), the extent of the ongoing public discourse within religious communities in Belarus about the role of the churches and religious values in the protests is exceptional. The politically active believers show an impressive resilience in maintaining Christian values under repression. We see the emergence of a Christian social ethics in the post-Soviet context, which includes the churches as an important part of civil society – a development still in its infancy in Ukraine and entirely lacking in Russia.

The analysis questions the approach to grasp the impact of church on state decisions and public opinion by measuring collaborations with state structures. The Belarusian case shows that none of the appeals from the ranks of the Orthodox Church leadership to end the violence impeded any effect on the behavior of state bodies. On the other side, Lukashenka’s public criticism of the churches’ public position indicates how concerned the regime is about the church mobilizing against it. The usage and subsequent prohibition of the religious hymn “Mahutnya Bozhya” underlines the disruptive power of religious symbols.

Finally, the intersection of religious actors and civil protest discussed above draws attention to the ongoing discourse about secularity, de-secularization, and post-secularity. Without a doubt, the current situation in Belarus illustrates the simultaneity of these concepts, which are often described as consecutive (on this discussion, see Stoeckl Reference Stoeckl, Giordan and Zrinščak2020). Declining religious practices and trust in religious institutions go hand in hand with A) religious patterns in politics, B) value discourses that reference religious narratives, and, not least, C) a democratic opposition sensitive to religious values and social paradigms. This mixture is an important piece in the puzzle of religion, civil protest, and democratization in post-Soviet societies. It has to be left to further studies to unpack the self-awareness of believers as part of the church and of civil society, as well as the role of social media for the ecclesial discourse.

Disclosures

None.

Financial Support

This article elaborates on survey data collected by the Centre for East European and international Studies ZOiS in December 2020 with the financial support of the German Federal Foreign Office.