Introduction

The period from the 1860s to the 1920s marks the golden age of photography in Transylvania (until 1918 East Hungary, thereafter Central Romania), as locally based photographers produced (and reproduced) seemingly endless images of natural landscapes, historical architecture, and especially “peasant types” (Almasy Reference Almasy2018, 44). These images and the photographers who took them have recently risen in prominence through the digitization of archives.Footnote 1 Scholars have excavated individual photographers and studios, and explored their photographic techniques, especially focusing on the much-admired ethnographic images, predominantly taken in studio in elaborately staged tableaux (Klein Reference Klein2007; Klein Reference Klein2015; Voina Reference Voina2011; Ionescu Reference Ionescu2010; e.g. Sigerus Reference Sigerus1929, Figure 1, Figure 3). Most scholarship treats these photographs as “authentic” portrayals of peasant material culture, despite their carefully constructed nature (Popescu Reference Popescu1998, 325; Voina Reference Voina2011, 314–315; Voina Reference Voina2008, 282; Ionescu Reference Ionescu2010, 70–71, 87). However, the same period also saw rising nationalism throughout the Habsburg Empire and its successor states. Hungarian, Romanian, and Saxon nationalists in Transylvania were not slow to recognize the potential of photographic images for asserting nationalist labels and claims to territory (Almasy Reference Almasy2018, 44–45), and, in a process comparable to the use of photography in colonial contexts, to categorize, define, and dominate the Other (Scherer Reference Scherer1990, 133), asserting competing national hierarchies in support of a special role for their specific nation within the region.

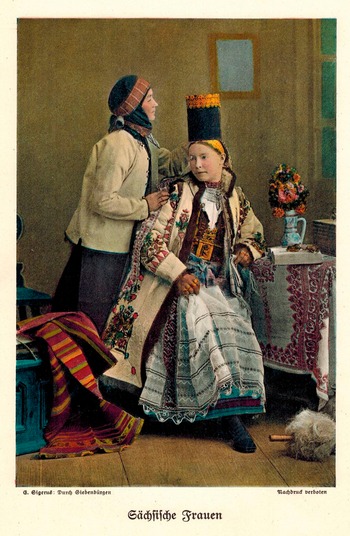

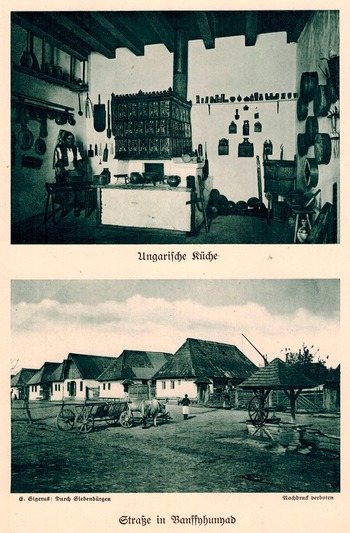

Figure 1. Anonymous, “Saxon Women.” Public Domain.

The lack of attention to political messaging in Transylvanian photography from this period partially reflects the sheer profusion of images, precluding any representative survey (Almasy Reference Almasy2018, 44). Furthermore, nationalist messages often came less in individual images than in their colligation, labelling, and arrangement relative to one another. Accordingly, I examine here one collection of images; Saxon historian, folklorist, and travel writer Emil Sigerus’ Durch Siebenbürgen: eine Touristenfahrt in 58 Bildern (Through Transylvania: a Tourist Trip in 58 Pictures), published repeatedly between 1905 and 1929.

Durch Siebenbürgen was a commercial venture in which Sigerus attempted to sell two products: the book itself, and Transylvania as an idyllic unspoiled travel destination. In doing so, Sigerus engaged in “place branding”: the systematic process of culturally constructing landscapes in response to the logic of the capitalist market, establishing “a conceptual context for consumption by creating associations between tangible objects (say for example a forest) and intangible values (like environmental purity or exoticness)” (Porter Reference Porter2016, 6–7). In this context, landscape is distinguished from physical environment in that landscape is a culturally informed way of seeing or imagining the land, produced in diverse media, including artwork, photographs, and text (Porter Reference Porter2016, 9–10). Sigerus was participating in the broader creation by European nationalists of what Thomas Etzemüller (Reference Etzemüller2019, 276–277), drawing on Benedict Andersen’s notion of “imagined communities,” refers to as “imagined landscapes”: popularizing remote areas as timeless, unspoiled antidotes to the evils of industrialization, and as bearers of symbolic significance to the nation.

Place branding is an important element in “nation branding,” in which “governments engage in self-conscious activities aimed at producing a certain image of the nation state” (Bolin and Ståhlberg Reference Bolin, Ståhlberg, Roosvall and Salovaara-Moring2010, 82), as a marketing activity directed outward towards, and conforming to the logic of, the global market (Bolin and Ståhlberg Reference Bolin, Ståhlberg, Roosvall and Salovaara-Moring2010, 95–96). Tourism constitutes a key element of nation branding, both as a means of benefiting the nation economically (Jordan Reference Jordan2014, 22), and of disseminating the national brand internationally (Freu and White Reference Freu, White, Freu and White2011, 215). Sigerus was, then, engaged in branding Transylvania to Saxon nationalists’ commercial benefit.

Such national branding was inherently competitive. Definitions of nation branding such as that offered by Göran Bolin and Per Ståhlberg (Reference Bolin, Ståhlberg, Roosvall and Salovaara-Moring2010, 82) above assume that states drive nation branding, and that the state and the nation are one and the same. Conversely, little consideration has been given to nation branding by non-state actors in multi-national regions like Habsburg and post-Habsburg Transylvania. As discussed below, Sigerus was one of many actors competing to foster tourism on nationalist lines in Transylvania, and to direct tourist flows to their nation’s benefit.

Place and nation branding in Durch Siebenbürgen also worked to benefit Saxon nationalists politically. While Bolin and Ståhlberg (Reference Bolin, Ståhlberg, Roosvall and Salovaara-Moring2010, 95–96) argue that nation branding need only respond to the global market, and can be at odds with the national self-image, I follow Paul Jordan (Reference Jordan2014, 22) in seeing nation branding as the commodification of the national self-image in the global market. Nationalists frequently place great ideological significance on the dissemination of the national self-image through tourism (Light Reference Light2001, 1054–1056), and too great a gap between nation branding and national image can provoke internal tensions (Smith and Puczkó Reference Smith, Puczkó, Freu and White2011, 43-44). Furthermore, tourist markets are often domestic as well as international, and tourism can also play a key role in disseminating images of the nation domestically (Pretes Reference Pretes2003, 127f). Durch Siebenbürgen was marketed to both local and international markets, disseminating a specifically Saxon nationalist view of Transylvania’s social hierarchy, and of the natural place of Saxons at its peak.

While most scholarly literature focuses on contemporary practices, nation branding extends back at least to the nineteenth century world fairs and expositions (Bolin and Ståhlberg Reference Bolin, Ståhlberg, Roosvall and Salovaara-Moring2010, 82; Aronczyk Reference Aronczyk2013, 3–4; Jordan Reference Jordan2014, 22). Far from presenting a monocultural vision of the nation at world fairs, multiethnic empires (the continental Habsburg Empire as much as overseas powers Britain and France) displayed imperial subjects in all their variety (Rampley Reference Rampley2011). Nation branding took the form of an assertion of a hierarchy of civilization within the empire, with the Staatvolk at the peak, engaged in a civilising mission legitimizing empire. Through the ‘objective’ medium of photographs, Sigerus asserted no less ambitious a Saxon view of Transylvania’s social hierarchy, legitimizing a Saxon “civilizing mission” in Transylvania, while directing tourists to specifically Saxon sites.

I begin below by positioning Sigerus as a participant in the intense nationalist competition in Transylvania, before considering the domestic photographic industry, and the publication history of Durch Siebenbürgen. I then examine in turn how Sigerus utilized photographs to brand Transylvania and the Saxon nation, projecting a nationally stratified social hierarchy on Transylvania’s heterogeneous population, with Saxons at the apex; asserting Saxon ownership of urban centers, thereby reinforcing Saxon claims to a “civilizing mission” in Transylvania; and staking claim to territory (simultaneously directing tourism to these areas above other parts of Transylvania). Throughout, Sigerus’ careful curation and arrangement of images lent an “objective” weight to his claims, belying the polemic nature of Durch Siebenbürgen.

Nationalist Competition in Transylvania

From the nineteenth century, three principal nationalist movements competed for influence in Transylvania: Hungarian, Romanian, and Saxon. Hungarian nationalists enjoyed a position of dominance in Transylvania, which from 1867 to 1918 formed part of Habsburg Hungary. Although constituting only 29 percent of the population, Hungarian speakers dominated the nobility and the Szeklers (formerly a privileged class of border guards, greatly reduced in circumstances by the twentieth century) and formed a portion of the peasantry. The absolute majority (58 percent) of Transylvanians were Romanians, who until 1918 were politically marginalized, constituting the majority of the peasantry. However, Romanians were also found amongst wealthier peasants, the lower nobility, and a rising urban middle class, the latter gaining prominence once Romania annexed Transylvania in 1918. By comparison, Saxons – including Sigerus – constituted only eight percent of the population, but dominated the larger towns, as well as forming a comparatively wealthy, land-owning peasantry. Formerly constituting a privileged estate (the Natio Saxones), Saxons were transformed into an ethnic minority by the erosion of those legal privileges in the nineteenth century (Wagner Reference Wagner1976, 423; Domonkos Reference Domonkos, Cadzow, Ludanyi and Elteto1983, 45–46; Szelényi Reference Szelényi2007). Finally, a nascent nationalist movement amongst the Roma (the other ethnicity portrayed in Durch Siebenbürgen), constituting 2.5 percent of the population, struggled to gain recognition from other nationalists (Hancock Reference Hancock, Crowe and Kolsti1991, 139–140). Roma were socially marginalized, mostly being landless labourers or small-scale artisans serving the rural economy. However, a minority achieved a measure of prosperity, especially as musicians (Hermann Reference Hermann1895, 14–19; Frazer Reference Frazer2001, 107–109; Barany Reference Barany2001, 50–63).

Socioeconomic stratification on ethnic lines, while always incomplete (Roth Reference Roth2001, 74–83; Mitu Reference Mitu2014, 10–11;), informed nationalist stereotypes and fuelled nationalist competition. Saxon nationalists were wedged between the politically dominant Hungarian elite (before 1918) and the numerically dominant Romanians, whose growing middle class competed for control of the towns Saxons had long considered their own. While reduced in legal status, Saxon nationalists nonetheless benefited from the material and cultural capital accumulated under the Natio Saxones. In 1890, the Deutsch Sächsisches Volkspartei (German Saxon People’s Party DSVP), successfully negotiated an agreement with the Hungarian government giving Saxon nationalists a free hand to pursue their aims through social and economic means in return for ending their opposition to Hungarian rule (Egry Reference Egry2006), a matter of pressing concern due to the relative economic stagnation of Transylvania in preceding decades (Kroner Reference Kroner1976, 23f). The DSVP reached a similar accommodation with the Romanian government following the First World War (Roth Reference Roth1994, 69–74, 96–104).

While Saxon nationalism remained parochial and particularist, Saxon nationalist historians also responded to their reduced status by framing their Saxon particularism, which was rooted in local customs, history, and traditions, in a broader sense of German cultural superiority, drawing on the wider myth of a Habsburg German civilizing mission in Southeast Europe (Judson Reference Judson2006, 15–16), pointing to their own historical role in founding urban centers in Transylvania, and their (greatly exaggerated) role in defending the region against Ottoman incursion (Roth Reference Roth, Gündisch, Höpken and Markel1998, 183–86; Teutsch Reference Teutsch1852). They contrasted Germans as a Kulturvolk (civilized people) to the other nations of Transylvania as less civilized, and even Naturvölker (primitive peoples) of varying degrees (Vari Reference Vari and Wingfield2005; Schwicker Reference Schwicker1881). Saxon ethnographers asserted a comparative, evolutionary view of folk culture, drawing on the comparative wealth of the Saxon peasantry as evidence of their superior standing to their Hungarian and Romanian neighbours (Schullerus [1926] Reference Schullerus1998; Sigerus [1922] Reference Sigerus and Stephani1977, 27). Like other nationalists, Saxons also took for granted that Roma were Naturvolk par excellence (Schwicker Reference Schwicker1883; Wlislocki Reference Wlislocki1890). Rival Hungarian and Romanian nationalists similarly asserted their own nations’ special contributions to region and empire. On the borders between scholarship and economics, a proliferation of nationally differentiated scholarly institutions, museums, and even tourist associations asserted these claims to their own nation’s special contribution to Transylvania and the Empire – and thus their right to special recognition (Judson Reference Judson2006, 68; Török Reference Török2017, 652; Heltmann, Reference Heltmann, Heltmann and Roth1990, 11, 19–20).

The Saxon nationalist scholar Emil Sigerus (1854–1947) occupied the intersection of history, ethnography, and tourism. An author of well-received works on the history of his hometown Hermannstadt (Sibiu, Nagyszeben),Footnote 2 church architecture, and Saxon folk culture, especially costume (Stephani Reference Stephani and Stephani1977), Sigerus was from 1881–1900 secretary of the Saxon-dominated Siebenbürgische Karpathenverein (Transylvanian Carpathians Association, SKV) (1880–1944), which encouraged travel through, educated tourists about, and symbolically laid claim to the Southern Transylvanian Carpathians (Heltmann Reference Heltmann, Heltmann and Roth1990, 11, 26; Szabó Reference Szabó2011, 11–12). As such, the SKV was typical of national tourist organizations that developed across Europe from the late nineteenth century (Etzemüller Reference Etzemüller2019, 289–290). Sigerus was also the driving force behind, and until 1903 the first director of, the SKV’s Ethnographic Museum (founded 1895), singlehandedly collecting many of its exhibits (Rill Reference Rill, Heltmann and Roth1990, 45–52). The SKV and its museum aimed both to strengthen Saxon nationalism domestically by fostering ties to landscapes imagined as nationally significant, and to attract tourists. Sigerus, then, was simultaneously engaged in both internal nation-building through promotion of a specifically “Saxon” folk culture to an internal audience, and in branding the region and Saxon nation to external tourists.

Sigerus’ fields of scholarly and commercial interest – history, folklore, and tourism – were all key arenas of nationalist struggle (Török Reference Török2017, 652–655; Heltmann Reference Heltmann, Heltmann and Roth1990, 11, 19–20). He brought those interests together in Durch Siebenbürgen, which enticed tourists to the region through photographs celebrating Transylvania’s rich history, beautiful landscapes, and cultural diversity. In doing so, Sigerus portrayed an imaginary and idyllic Transylvanian landscape characterized by unspoiled nature, and by peoples and architecture untouched by time. Simultaneously, Sigerus asserted through Durch Siebenbürgen a specifically Saxon nationalist view of the Transylvanian landscape and social order in which Saxons fulfilled a special civilizing mission by virtue of their ethnic German culture, and lay claim to key parts of Transylvania.

Durch Siebenbürgen and the Transylvanian Photographic Industry

First published in 1905 in German, Hungarian, and Romanian editions (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1905a; Sigerus Reference Sigerus1905b), Durch Siebenbürgen was likely based upon a similarly titled lantern slide collection and accompanying lecture published fifteen years earlier (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1890).Footnote 3 Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1917, 3; 1929, 3) wrote Durch Siebenbürgen for an international audience, hoping to spark in its readers the desire to travel to Transylvania, “an almost unknown wonderland in the heart of Europe!”Footnote 4 While he had co-authored a conventional travel guide two years previously (Bielz and Sigerus Reference Bielz and Sigerus1903a), Durch Siebenbürgen was an ambitious collection of 58 photographs of natural landscapes, townscapes, architecture, and especially ethnographic studies, including eight colored chromolithographs, all loose-leaf bound to allow for removal and display. An introductory text accompanied the photographs, tracing a circular route through Transylvania, starting in the southwest and working counterclockwise through the region.

Sigerus could draw on an extensive photographic tradition. The first permanent Transylvanian studios were founded in the early 1850s (Ittu Reference Ittu2018, 174–175); by the 1860s, Transylvanian photography had reached a level admired by West Europeans (Klein Reference Klein2007, 23), especially for its ethnographic photographs capturing the wide variety of national and regional folk costumes (Ionescu Reference Ionescu2010, 70). Theodor Glatz (1818–1871) and Carl Koller’s (1838–1889) catalogue of folk costumes around Hermannstadt and Bistritz (Bistrița, Beszterce) (Figure 2), one of the first systematic photographic surveys of folk culture in the Habsburg Empire (Klein Reference Klein2015, 128–129), won awards at several European exhibitions, and started what became an artistic school of ethnophotography in Transylvania (Klein Reference Klein2007, 28–33). Like imperial displays at world fairs and international expositions, such touring collections commodified the diversity of imperial subjects. Sigerus reproduced, amongst others, “classics” by leading Transylvanian photographers including Glatz and Koller, Leopold Adler (1848–1924), Emil Fischer (1873–1965) and Ferenc Dunky (1860–1940?) (Klein Reference Klein2007, 36).

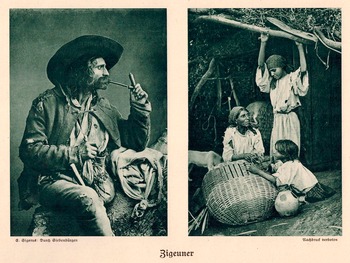

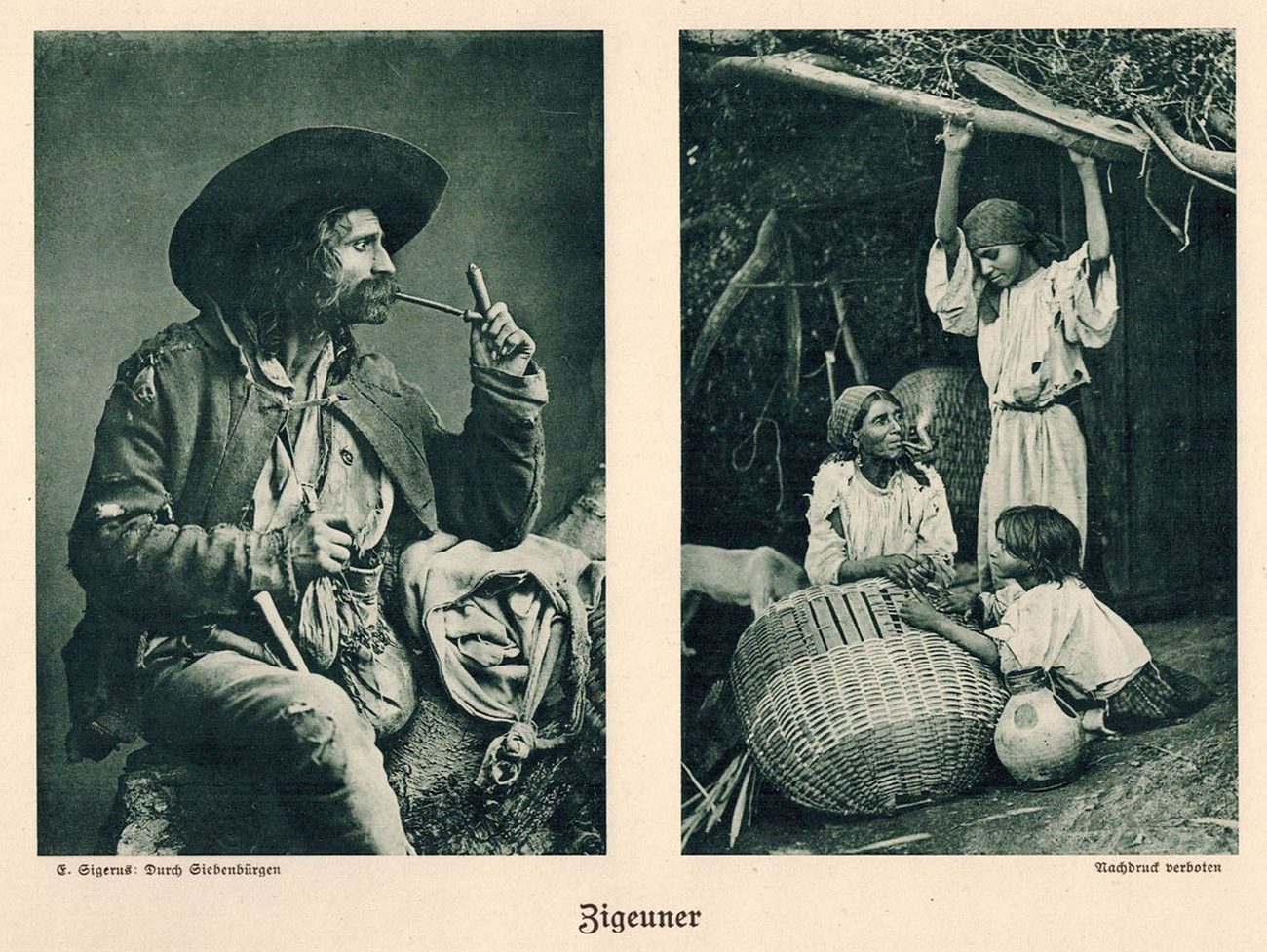

Figure 2. K. Koller (left) and T. Glatz/C. Asboth (right), “Gypsies.” Public Domain.

Advertised widely in publication lists in Europe and North America, and receiving favorable reviews (e.g. Anonymous 1905, 280), the German-language version of Durch Siebenbürgen was one of the most successful books printed by Transylvania’s leading photographic publisher, Hermannstadt-based Joseph Drotleff (Klein Reference Klein2007, 36). A second edition was published in 1910 with 62 images. It was reissued in 1917, still labeled as the second edition, but with 60 images and an expanded text including recent events of the First World War. This edition was marketed as a souvenir for soldiers in the German army who had relieved Transylvania from invasion by Romania in 1916 and were now occupying that country; Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1917, 3), thereby sought to take advantage of new interest from Germany in the isolated Transylvanian Saxons, fostered by increased interactions with German troops and the common experiences of the war (Philippi Reference Philippi and Rothe1994, 80.). The third and fourth editions, published in 1925 and 1929, contained 58 images and the subtitle altered from Touristenfahrt [Tourist Trip] to Wanderung [Ramble].Footnote 5 This renaming reflected the popularity in the German speaking world of organizations such as the Wandervogel [Wandering Bird] youth groups, who embraced a romanticized view of hiking through the natural landscape (Williams, Reference Williams2001 ). The book was also marketed to a domestic Saxon readership under the slogan: “Every Saxon house should be adorned with at least one of Emil Sigerus’ three magnificent works” (Anonymous 1912, 181). The venue, the Kirchliche Blätter, had a predominantly educated middle class readership, who might be expected to be able to afford the not inconsiderable price of 30 Kronen. Conversely, the Hungarian- and Romanian-language editions also published in 1905 were flops: “neither found any buyers, where two editions of the German version quickly sold out.” The unsold copies’ photographic pages were ultimately combined with new German language text to produce the 1917 edition (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1917, 3).

Despite minor changes, most images and text in Durch Siebenbürgen remained consistent throughout its editions, including photographs and textual descriptions of landscapes, architecture, and folk culture considered important to Romanian and Hungarian, as well as Saxon nationalists. Sigerus is remembered for his contributions to Romanian as well as Saxon ethnography; he was “not only one of the most important ethnographers of the Saxon minority … but also as an ambassador of Romanian popular culture” (Negoescu Reference Negoescu2012, 96). Nonetheless, Durch Siebenbürgen, the images Sigerus selected, and the way he described them strikingly reflected his Saxon nationalism.

Below, I highlight how Sigerus used photographs in Durch Siebenbürgen to assert three key claims. Firstly, Sigerus used ethnographic photographs to assert a civilizational hierarchy of national cultures in Transylvania, a claim he reinforced through village architecture. Secondly, Sigerus selected and labeled townscapes ethnically to construct a hierarchy of urbanity. Finally, he assembled photographs ethnically and geographically to assert nationalist claims to territory, and to direct tourism to Saxon areas of settlement.

Asserting a Peasant Hierarchy

The crowning glory of Durch Siebenbürgen were its ethnographic photographs of Hungarian, Romanian, Saxon, and Romani “folk types.” Nationalists in the Habsburg Empire viewed peasants as the embodiment of cultural authenticity (Rampley Reference Rampley2011, 113), driving the proliferation of competing nationalist ethnographic societies and museums – such as Sigerus’ SKV Museum (Johler Reference Johler2015, 53). Transylvanian nationalists celebrated the region’s relatively isolated, undisturbed agricultural economy (even by Habsburg standards) as evidence of “pure, authentic” peasant culture (Hegedűs Reference Hegedűs and Mitu2014, 41–46). Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 5) reinforced these views, extoling Transylvania’s folk cultures, and especially folk costume, as one of the region’s key attractions:

These peoples have not only preserved their language, their customs and traditions, but also their beautiful old folk costumes, which are full of picturesque charm. And if in the tourist countries of Western Europe you can only find folk costumes in the most remote valleys, here in Transylvania there is no need to look for them at all; the original folk culture is evident to all, and all nations living in the land have alike carefully guarded the old costumes as inherited treasures.

Transylvanian nationalists took a strong interest in folk costume, which provided the main visual indicator of ethnicity in the absence of racial difference (Anonymous 1926: 9–10; Müller-Langenthal Reference Müller-Langenthal1927, 94–95). Even the Saxon völkisch far right, while rooting ethnic difference in race, considered folk costume the principal external marker of ethnicity (Davis Reference Davis and Smith2010, 206–209). To Saxon ethnographers, folk costume also provided evidence of the Saxons’ specifically German folk culture, and therefore high cultural standing. Saxon nationalists interpreted the wearing of folk costume as a declaration of one’s loyalty to the nation (Römer Reference Römer and Siegmund1922, 308−311); representations of the ideal Saxon home emphasized embroidered linen patterns and the rich, home-made folk costume of its denizens (Schullerus [1926] 1998, 22–36).

Sigerus was unstinting in his praise for Transylvanian costume, regardless of its national identification, for example admiring Romanian and Hungarian folk costume from the Hatszeg and Kalotaszeg Valleys respectively (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1929, 6–7, 14–15). He was himself a noted scholar of not only Saxon but also Romanian traditional costume and folk motifs, donating his own collection of Romanian material to the SKV Museum (Stephani Reference Stephani and Stephani1977, 15). Nonetheless, Sigerus emphasized Saxon folk culture over that of other cultures, including seven images of Saxon folk costume and crafts (e.g. Figure 1), (including half of the eight chromolithographs), compared to six images of Romanian (e.g. Figure 8),Footnote 6 and only four each of Romani (e.g. Figure 2) and Hungarian (e.g. Figure 3) folk culture.

Figure 3. K. Koller, “Hungarian Peasants from Toroczko.” Public Domain.

Furthermore, Sigerus used ethnographic images to reinforce his assertions of a hierarchy of civilization in Transylvania. Habsburg ethnographers elaborated a cultural succession in the development of folk cultures (Johler Reference Johler2015, 67), predominantly marked by material wealth. These stereotypes ignored variation in socioeconomic standing within ethnic categories, instead representing nations as belonging to specific economic classes. They rooted this stratification in national and even racial difference, rather than seeking socioeconomic causes (Rampley Reference Rampley2011, 120–127). This comparative, evolutionary approach itself led to the maintenance in ethnography of hierarchies of civilization (Vari Reference Vari and Wingfield2005); ethnography in Transylvania, then, became a competitive act of asserting one’s nation’s position within an ethnic hierarchy (Szabó Reference Szabó2011, 19–24). Folk costume, physical artifacts, and architecture all provided visual evidence of that culture (Rampley Reference Rampley2011, 123); photography, imbued with a special authenticity as a mechanical process, provided a means of cataloguing material culture on nationalist lines (Scherer Reference Scherer1990, 132; Tari Reference Tari1990, 171).

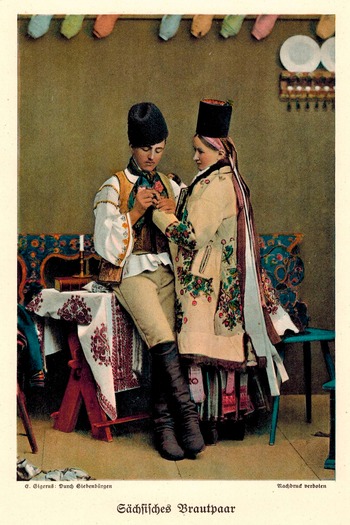

Many ethnographic images in Durch Siebenbürgen date to the nineteenth century, when images had to be staged due to long exposures (Howells and Negreiros Reference Howells and Negreiros2012, 186). While some photographers took photographs in situ (Klein Reference Klein2007, 27, 32), most ethnographic images were shot in studio in urban centers like Hermannstadt. Photographers would go to the town square on market or festival days and induce passing peasants in picturesque costume to pose for photographs, often by offering the subject a print of the photograph (Ionescu Reference Ionescu2010, 71). This approach was considerably easier than persuading less worldly peasants in more isolated villages to pose (Vikar Reference Vikar1891, 121–122). As Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 8) noted, urban markets were exceptionally rich sources of folk costume: “people from all over Transylvania in their colourful national costumes flow into the city … At such a fair you can find a rush of picturesque motifs in all streets.” Photographers created elaborate tableaux with backgrounds and props, recreating the region from which the model came (Ionescu Reference Ionescu2010, 71). As many photographers were also painters, they composed their own backdrops creating the appearance of outdoor scenes (Ionescu Reference Ionescu1989, 279; Emil Fischer, “Romänen aus Pojana,” in Sigerus Reference Sigerus1929). Other images were repurposed wedding photographs (e.g. Figure 4); it was customary for wedding couples to don their finest festive costume for their wedding.

Figure 4. Anonymous, “Saxon Bridal Pair.” Public Domain.

Scholars of Transylvanian photography have emphasized the “authentic” quality of these photographs as evidence of Transylvanian folk culture. Delia Voina (Reference Voina2011, 313–314), archivist at the ASTRA Museum (whose photographic holdings include those from Sigerus’ SKV Museum), asserts that the variations in material circumstances portrayed in photographs from the period accurately reflect the ethnic stratification of Transylvania on socioeconomic lines, and that “the photographer did not pursue beauty or ugliness, defects or qualities, poverty or wealth” (Voina Reference Voina2011, 315). Art historian Adrian-Silvan Ionescu (Reference Ionescu2010, 71) notes the care with which tableaux were created: “if some compositions are ‘staged’ in the studio, then the same, stereotypical decoration is never used, but the background is always different, depending on the relief and flora of the area from which the model comes,” giving these images a “scientific” accuracy (Ionescu Reference Ionescu2010, 87). Certainly, contemporary ethnographers unquestioningly accepted such staged photographs (Tari Reference Tari1990, 170; Voina Reference Voina2010, 120–125).

Photographers and curators such as Sigerus, however, selected their subjects to portray preconceived “archetypal” folk cultures. In the process, subjects became “impoverished signifiers,” no longer marking an individual, rather a national “type” (Barthes Reference Barthes1989, 126–128; Popescu Reference Popescu1998, 325–326). Photographers did not create these categories, instead reflecting the values of the society in which they lived (Howells and Negreiros Reference Howells and Negreiros2012, 102–103); these distinctions were desired and accepted as “natural” by the purchasing public (Scherer Reference Scherer1990, 141). Nonetheless, by repetition, the photographers also reinforced these categories, and the stereotypes that went with them, in the public imagination (Thorpe Reference Thorpe2015, 42). Sigerus further reinforced these stereotypes through his selection and arrangement of the images. The history of such images being used to assert normative social relations in Transylvania predated photography, with the publication of collections of picturesque engravings from the early nineteenth century (Born Reference Born2011; Anonymous 1813; Heinbucher Reference Heinbucher1820).

Sigerus emphasized ethnic segregation in his selection and labeling of ethnographic photographs. Despite the variety of folk costume captured in Durch Siebenbürgen, the individual photographs bear monocultural titles; they purport to show “Saxons,” “Romanians,” “Hungarians,” and “Gypsies” [Zigeuner] individually or collectively, but never together. These images created the illusion of monoethnic rural tradition, rather than displaying the subjects in the multi-ethnic, often urban environment in which the photographers found them. While photographs showing the coexistence of different ethnic groups are extant in the archives (Voina Reference Voina2011, 314–315), Sigerus instead selected images emphasizing ethnic separation and distinct national folk cultures. Despite efforts to delineate “national” folk costumes, Saxon ethnographers, including Sigerus ([1909] Reference Sigerus and Stephani1977), were aware of extensive borrowings between folk cultures across linguistic lines (Orend Reference Orend1924, 184–188; Schullerus [1926] Reference Schullerus1998, 60ff; Müller-Langenthal Reference Müller-Langenthal1927, 95–96). However, Sigerus made no mention in Durch Siebenbürgen of borrowings between the principal cultures in Transylvania.

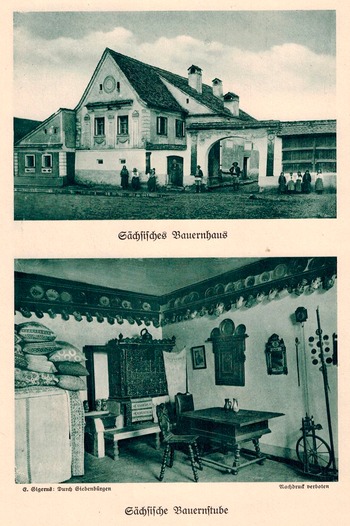

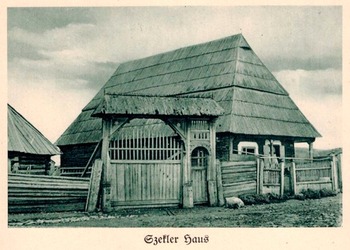

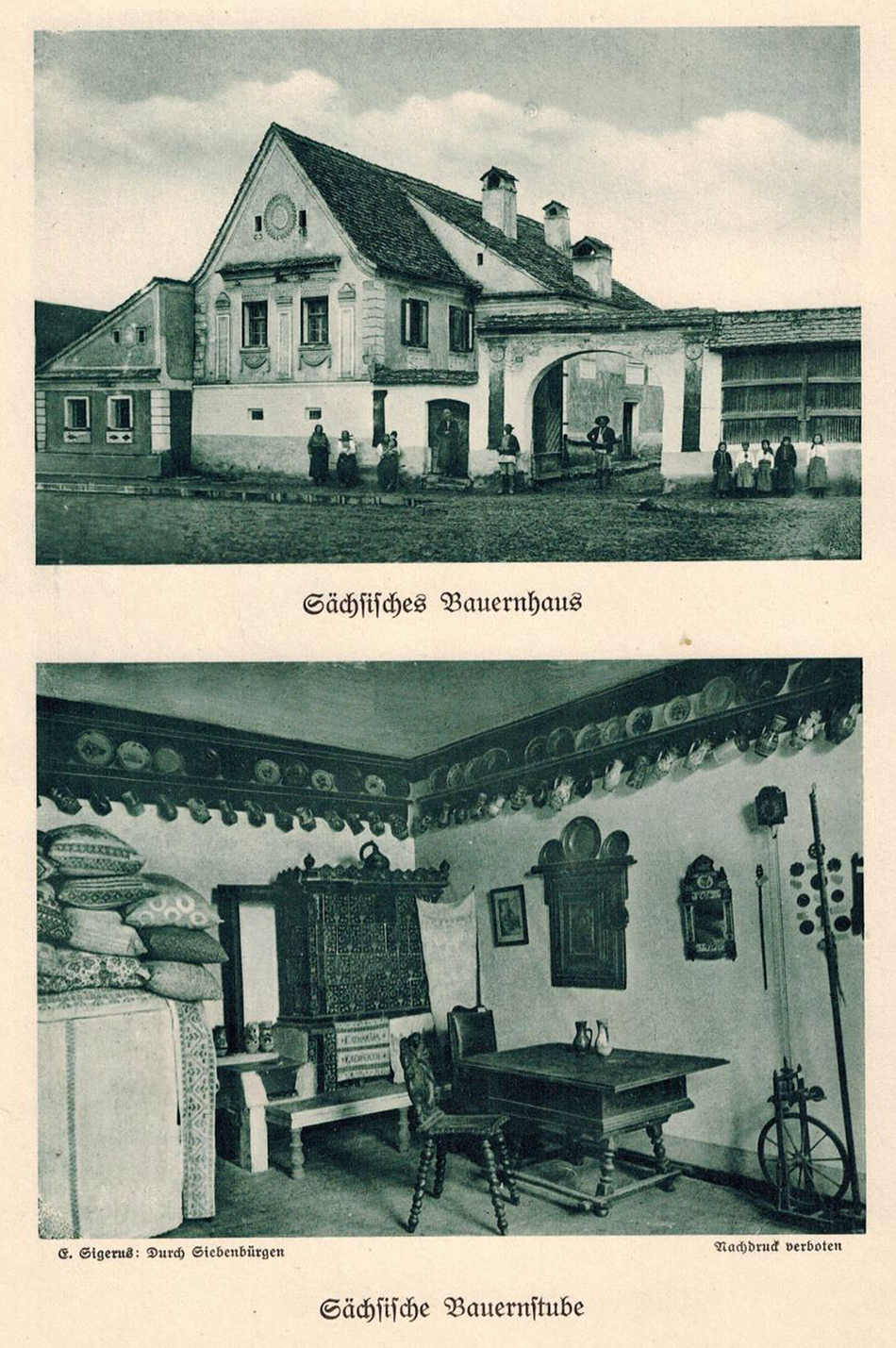

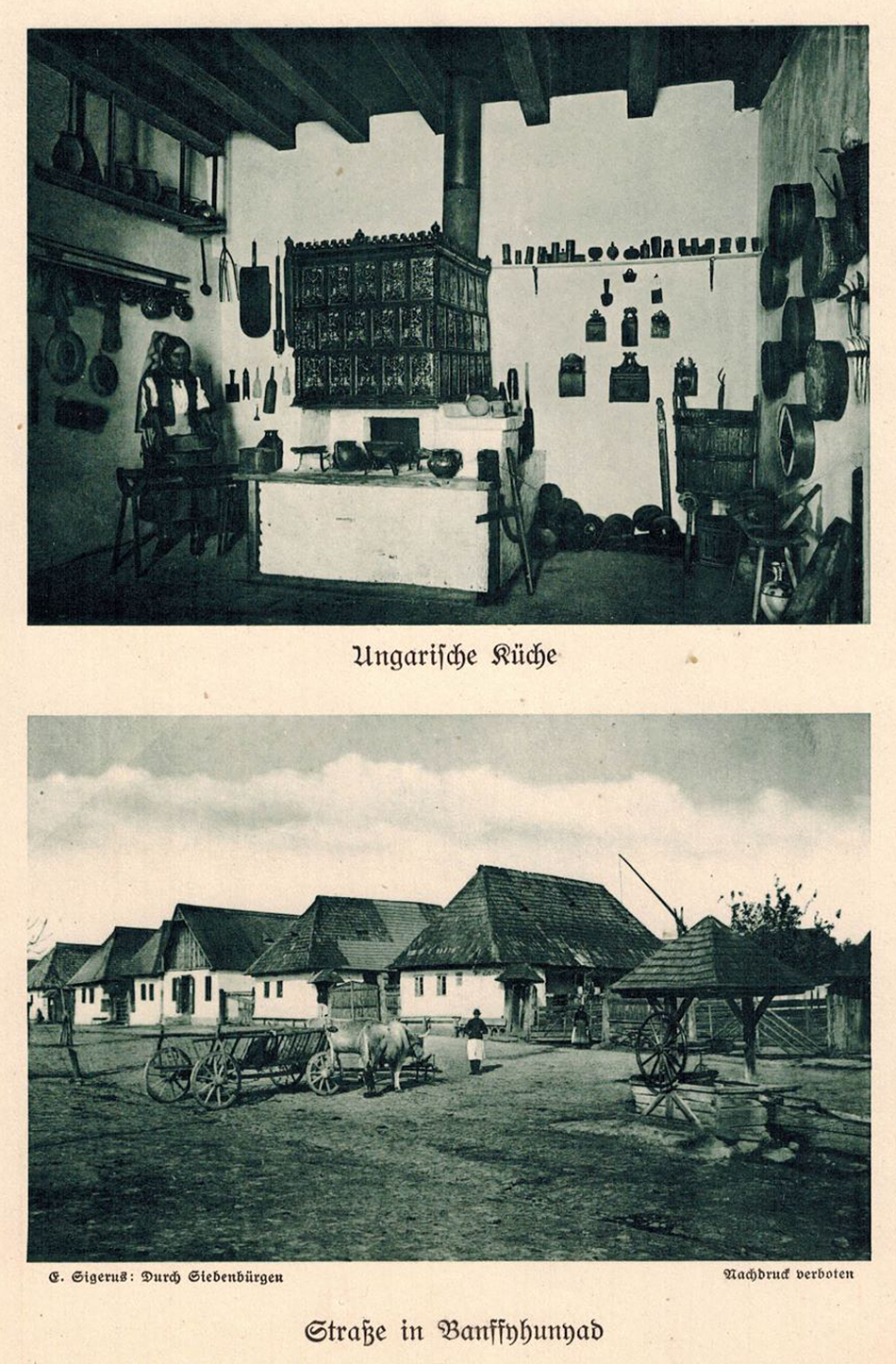

Sigerus further drew on widely held stereotypes to assert a comparative hierarchy of peasant cultures in Transylvania. Firstly, Sigerus subtly asserted the status of Saxons and Hungarians as Kulturvölker by including images of Saxon and Hungarian peasants indoors, surrounded by extensive displays of material culture, especially fabrics and ceramics. The rooms were richly appointed. In “Saxon Peasant Women” (Figure 1) the photographer placed a distaff on the floor. Ethnographers often included the tools of textile production in photographs, even though women did not wear their festive best to spin or sew (Tari Reference Tari1990, 171); such tools underlined both the “authenticity” of the women’s costume and the fabrics decorating the room the fabrics, and that they were the product of the subjects’ diligence and industry. The two Saxon interiors Sigerus selected (Figures 1, 4) were more richly appointed than the Hungarian interior (Figure 3), asserting a subtle hierarchy between Saxons and Hungarians. Nonetheless, Sigerus represented both peoples as Kulturvölker, reinforcing this impression with pictures of Saxon and Hungarian peasant kitchens (Figure 5 lower, Figure 6 upper).

Figure 5. W. Aurich, “Saxon Peasant House and Saxon Peasant Kitchen.” Public Domain.

Figure 6. Anonymous, “Hungarian Kitchen” and “Street in Bannfy-Hunyad.” Public Domain.

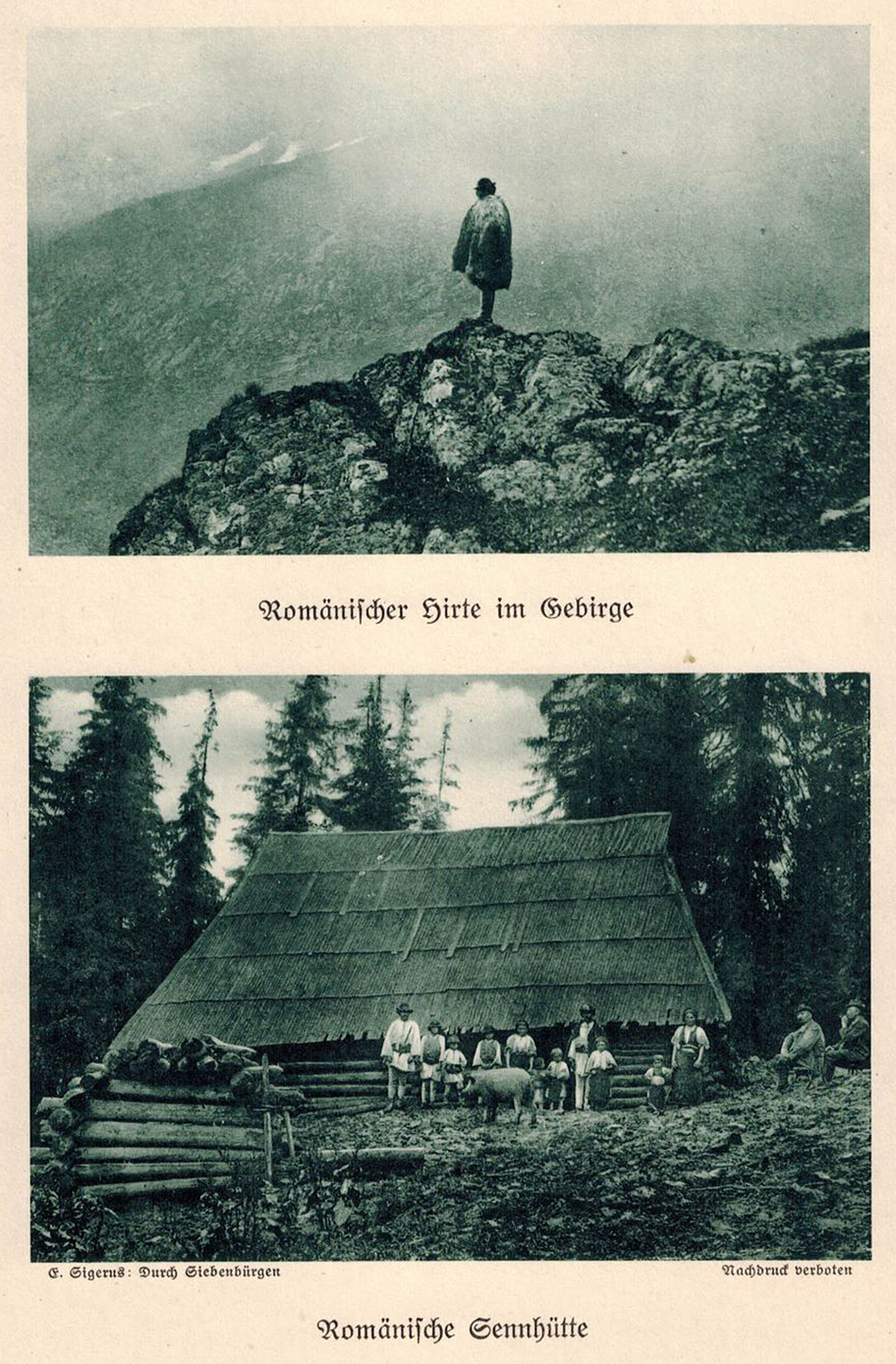

Conversely, all six images of Romanian peasant types Sigerus selected were set outdoors. Particularly striking is an in-situ photograph of a Romanian shepherd in the mountains (Figure 8, upper), surrounded by no signs of civilization; Saxon stereotypes of Romanians emphasized a connection to the Carpathian Mountains ringing Transylvania – and to wildness (Heitmann Reference Heitmann, Gündisch, Höpken and Cologne1998, 35–37). Sigerus included no images of Romanian peasant kitchens. This was a choice of both the photographers and Sigerus as curator; half of these “outdoor” images were studio shots before backdrops. This emphasis on Romanians outdoors increased over time; pre-war editions of Durch Siebenburgen included a Romanian interior tableau that was dropped from interwar editions (“Romänische Bauern aus Hermannstadt” in Sigerus Reference Sigerus1917). Of the four photographs Sigerus included of Roma, two were taken in situ outdoors, one “outdoors” in studio, and only one indoors, Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 6) further emphasized material poverty through the selection of Roma in “picturesquely ragged” costume (Figure 2), a common trope in non-Romani representations of Roma. By comparison, non-Romani observers frequently considered well-dressed Roma “inauthentic” (Davis Reference Davis2019). Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 6) further reinforced the wildness of Roma by grouping their photographs with, and describing them in the same paragraph as, Transylvania’s cattle and buffalo. Thus, he contrasted Romanians and Roma as Naturvölker to the “cultured” Saxons and Hungarians.

Sigerus reinforced his view of the ethnic hierarchy through images of vernacular architecture. A grand two-story building (Figure 5, upper) represented the Saxon farmhouse; the reader could be forgiven for thinking that the ornate Saxon kitchen directly below on the same page, showing a wealth of material possessions (Figure 5, lower), was a photograph of the farmhouse’s interior. In fact, the photograph showed a reconstructed Saxon peasant interior from Sigerus’ SKV museum (Rill Reference Rill, Heltmann and Roth1990, 46), a fact alluded to in the accompanying text, but not in the photograph’s label (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1929, 8).

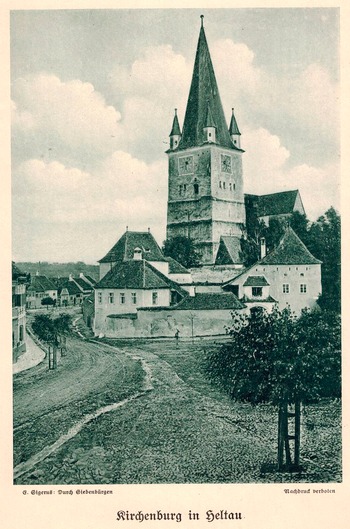

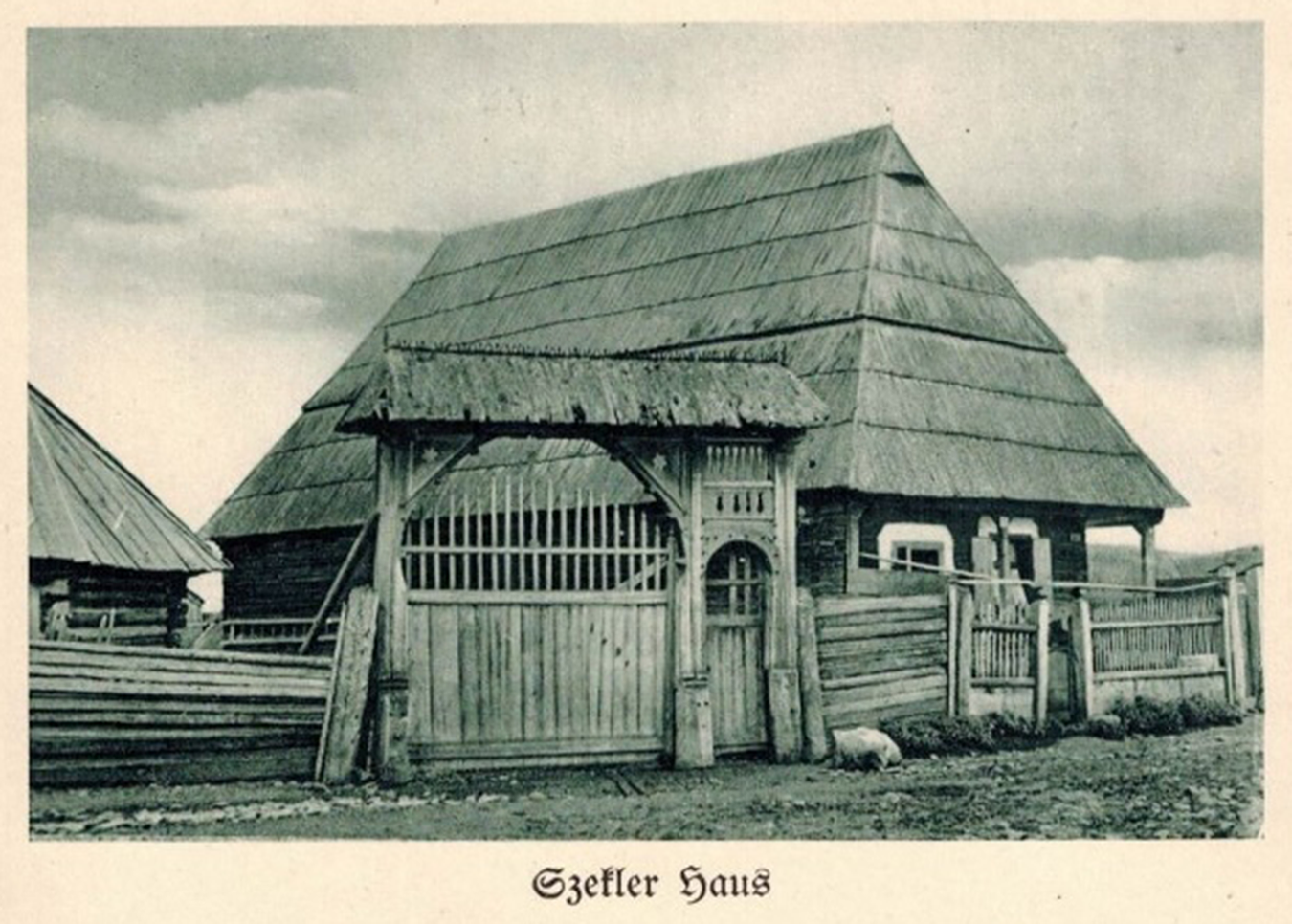

Conversely, Sigerus included a photograph of a more modest, single-story Hungarian home (Figure 7), while representing Romanian vernacular architecture with a simple shepherd’s hut, likely to be used only as a summer dwelling (Figure 8, lower). Figures of Romani housing are particularly striking. By the late nineteenth century, almost 90 percent of Roma were permanently settled, and the state classed only 3.25 percent as nomadic or “wandering Gypsies” (Wanderzigeuner) (Hermann Reference Hermann1895, 14–19). Furthermore, 62 percent of Roma lived in accommodation broadly comparable to that of their non-Romani neighbors (Szabó Reference Szabó1991, 103–12). Nonetheless, Sigerus selected two images of so-called “wandering Gypsies,” alongside one image of a particularly derelict Romani hovel (Figure 2, right).

Figure 7. Anonymous, “Szekler House.” Public Domain.

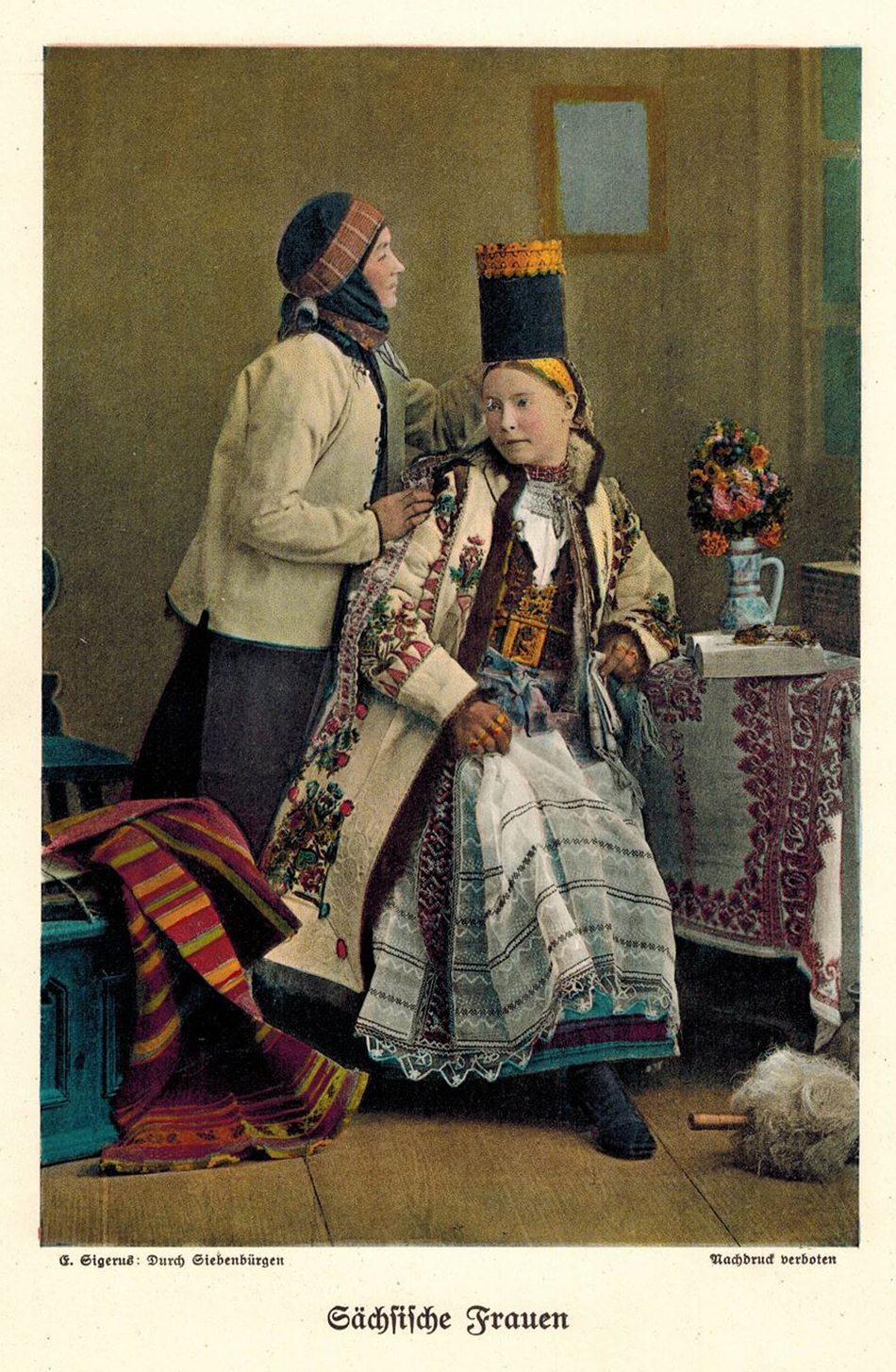

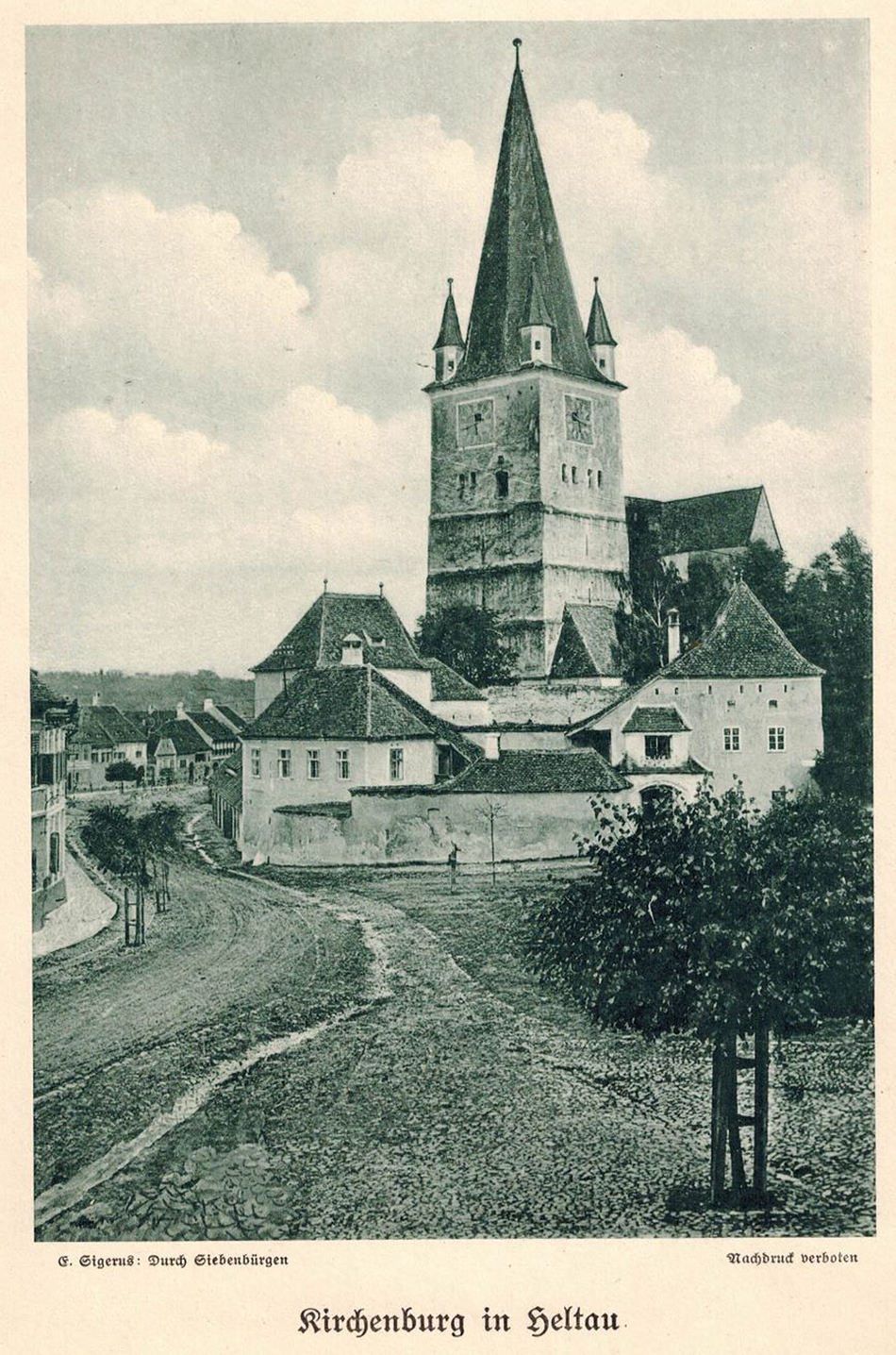

Sigerus reinforced this hierarchy through sacred village architecture, including a photograph of a Lutheran fortified church (Figure 9). Religious divisions reinforced ethnic distinctions in Transylvania; most Saxons – including Sigerus – were Lutheran, while Hungarians tended to Calvinism, Unitarianism, and Catholicism, and Romanians to Eastern Orthodoxy and the Uniate Church (Domonkos Reference Domonkos, Cadzow, Ludanyi and Elteto1983, 45–46). Saxon nationalists interpreted fortified churches, found in most Saxon villages and built by Lutheran parishioners as a stronghold in case of attack, as expressions of commitment to both faith and nation (Schullerus [1926] 1998, 16–17). To Sigerus, the fortified churches also spoke to the moral character of the Saxon peasants. Saxon nationalists asserted that their peasant ancestors had migrated to Transylvania in the twelfth century to preserve their freedoms from growing oppression in Germany (Teutsch Reference Teutsch1852, 20). Drawing on this myth, Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 9) argued that the fortified churches were “powerful witnesses to the courage, sacrifice and energy of their builders, who were free German farmers.” Sigerus drew no similar conclusions about moral character regarding an image he included of a Romanian Orthodox church. He associated no religious architecture with Roma, reinforcing widespread stereotypes of Roma as irreligious (e.g. Schwicker Reference Schwicker1883, 133f), despite Roma belonging to all major religions in Transylvania.

These representations reinforced the stereotypes of Transylvanian society as rigidly stratified on ethnic lines. None of the images represented the many exceptions to this stratification, such as prosperous Roma, poor Saxon peasants and wealthy Romanians. A proliferation of nationally segregated agricultural cooperatives from the late nineteenth century modernized agriculture, intensifying both social mobility and nationalist competition (Wallner Reference Wallner1993, 27; Wagner Reference Wagner1981, 9; Davis Reference Davis2014). The redistribution of land from (primarily Hungarian and Saxon) larger landowners to (predominantly Romanian) land-poor peasants in the 1921 Agrarian Reforms further transformed the rural social structure while raising nationalist tensions (Roth Reference Roth1994, 85–89; Verdery Reference Verdery1983, 278). Voina suggests that the number of images of prosperous Romanians portrayed in archival collections increased over the nineteenth century in line with rising Romanian prosperity (Voina Reference Voina2011, 314). However, the images Sigerus chose frequently dated back to the late 1860s and early 1870s (Klein Reference Klein2007, 31); by the 1929 edition, some images were sixty or more years old. Furthermore, neither nationalist conflict nor the modernization of agriculture were attractive to potential tourists. By excluding these developments, Sigerus instead maintained stereotypes from an earlier period.

There are several reasons Sigerus may have preferred to use older images, not least the desire to avoid paying for new photographs. Older images were ascribed with greater “authenticity.” The same expanding rail network that integrated Transylvania into the European tourist network simultaneously spread cheap and easily purchased mass-made fabrics and clothing to the countryside, threatening folk culture. By the interwar period, Sigerus’ assurances to the contrary notwithstanding, the daily wearing of folk costume was increasingly restricted to isolated villages (Schullerus [1926] Reference Schullerus1998, 59–60; Wolff [1910] Reference Wolff and Kroner1976, 193–194). As folk costume was relegated to festive wear, or abandoned completely, nationalists placed increasing significance on its preservation (Davis Reference Davis and Smith2010, 204–205). Many Transylvanian ethnographers followed German anthropologist Adolf Bastian (1826–1905) in seeing the task of ethnography as recording vanishing cultures (e.g. Wlislocki Reference Wlislocki1890, 49–51). Sigerus, for example, sought a “last chance” to collect peasant material for the SKV before it disappeared (Rill Reference Rill, Heltmann and Roth1990, 46). For ethnographers, the earlier a photograph had been taken, the more likely it was to represent “authentic” culture undisturbed by this process. Such populations, “untouched” by time, were also central to the European ascription of mythological nationalist properties to “Imagined Landscapes” (Etzemüller Reference Etzemüller2019). However, these older images also reinforced a consistent social hierarchy, emphasizing Saxon superiority.

Through photographs, then, Sigerus presented an ossified image of Transylvanian folk culture to brand Transylvania as a tourist destination that modernization had not besmirched. However, he also promoted Saxon folk culture over other cultures in the region, branding Saxons as possessing a particular cultural weight and authenticity. He simultaneously presented an outdated view of socioeconomic relations supporting a hierarchical view of Transylvania’s cultures, branding Saxons as the peak of civilization in Transylvania. He reinforced that civilizational hierarchy through his representation of urban settlements, discussed below.

Asserting Urbanity, Disguising Modernity and Social Mobility

While nationalists in the Habsburg Empire looked to the peasantry for “authentic” culture, they considered urban centers to be key evidence of their nation’s civilized status. Saxon nationalists asserted a historical civilizing role in Transylvania, through their settling of a desert land, and particularly through their founding of towns as centers of superior, “German” culture (Teutsch Reference Teutsch1852, 22, 51). Sigerus similarly used the multiple townscapes and cityscapes in Durch Siebenbürgen to assert that the Saxons’ German culture marked the epitome of civilization in Transylvania, demonstrating their special contribution to the region. Sigerus included images of five large towns, of which he identified four as “Saxon”: his birthplace Hermannstadt, Mediasch (Mediaş, Medgyes), Schäßburg (Sighișoara, Segesvár), and Kronstadt (Brașov, Brassó). Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 13–14) identified the fifth, Klausenburg (Cluj-Napoca, Kolozsvár), as founded by Saxons, but having “gradually lost its German character,” becoming Hungarian. Conversely, the other settlements that Sigerus identified as non-Saxon were small: the Hungarian market town of Banffy-Hunyad (Huedin)Footnote 7 (Figure 6, lower) and the Romanian village of Reschinar (Rășinari, Resinár). This arrangement presented Saxons as the principal urban population, while largely relegating Hungarians to secondary centers and rhetorically (and visually) excluding Romanians from urban centers. Reinforcing the status of Roma as a Naturvolk, Sigerus identified no settlement with the Roma, despite the many Romani satellite communities on the outskirts of towns and villages.

Through cityscapes, then, Sigerus asserted an image of Saxons at the apex of Transylvanian civilization. The emphasis on “Saxon” towns in part reflects the principal role Saxons played in founding urban settlements in Transylvania (Gündisch Reference Gündisch1998, 33–46). Furthermore, residence in towns of the Natio Saxones had been restricted to estate members, while (predominantly Hungarian, Romanian and Romani) non-citizens were relegated to suburbs outside the medieval town walls. While such restrictions ended in 1781 (Gündisch Reference Gündisch1998, 124–125), Saxons continued to dominate historic town centers. However, all four towns Sigerus identified as “Saxon” had multi-ethnic populations. For example, in 1913 “Germans” (predominantly Saxons) made up barely more than 50 percent of Hermannstadt’s population, followed by Romanians (26 percent), and Hungarians (22 percent). By 1930, the German population had fallen to 44 percent (Kósa and Zentai Reference Kósa and Zentai2001, 143; Wagner Reference Wagner1976, 418). Upwardly mobile non-Saxons increasingly penetrated the old town centers. A rising Romanian urban middle class particularly discomforted Saxon nationalists, especially after Romania annexed Transylvania in 1918 (e.g. Pl[attner] Reference Pl[attner]1919, 1), engendering new Saxon stereotypes of the boorish, nouveau riche middle-class Romanian as disconnected from authentic Romanian peasant culture, while lacking an organic connection to urban life (Zillich Reference Zillich1926, 385–386.). Saxon nationalists also worried about the emergence of a new Saxon working class in the outer suburbs, outside the reach of the traditional Lutheran parish system and (it was feared) vulnerable to the predations of internationalist socialism (e.g. Hermann Reference Hermann and Brandsch1930). However, accounts of nationalist rivalries were unlikely to be attractive to international tourists – and social mobility did not match Sigerus’ assertion of a population unspoiled by the passage of time.

Sigerus also excluded images suggesting urban modernization. The urban photographs Sigerus selected for Durch Siebenbürgen were long distance townscapes capturing towns as a whole, and rendering the inhabitants too small to be seen, although individuals are sometimes present in streetscape photographs from smaller settlements. While absence of people may have reflected long exposure times, the contrast between the many “peasant types” (often shot in urban studios) and the absence of images of urban dwellers is striking. While Saxon nationalists extolled the historical importance of Saxon burghers, ethnographers viewed towns as sites of cultural loss. Urban folk costume in particular was displaced by mass-produced Western costume during the nineteenth century (Schullerus [1926] 1998, 59–60). Consequently, urban dwellers provided few opportunities to reinforce the picturesque image of Transylvania as a landscape untouched by time. Conversely, Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 14) described only one town as “modern”: the no-longer-German Klausenburg.

Sigerus, then, branded Saxon towns as having particular cultural and historical importance. Once again, he excluded complexities of social mobility and cultural change in favor of outdated stereotypes conveying historic authenticity and asserting a specifically Saxon character for Transylvania’s urban settlements. Such claims again branded Transylvania as an attractive tourist destination and Saxons as simultaneously the peak of local civilization and bearers of a well-preserved cultural legacy. He also used urban centers, along with peasant types, to lay claim to territory, as discussed below.

Directing Tourists, Laying Claim to Territory

While primarily a photographic collection, Durch Siebenbürgen also described a tourist trip through Transylvania. Sigerus ordered the images geographically, grouping together landscapes, architectural photographs and peasant types along the route described in the introductory text. This geographical arrangement served two purposes: to lay symbolic claim to territory, and to direct tourism to areas best serving Saxon economic interests.

Firstly, Sigerus labeled the images and regions ethnically, juxtaposing landscapes and townscapes with ethnographic photographs of the purported inhabitants to assert a national map of Transylvania. In doing so, Sigerus had to navigate the competing territorial claims of other nationalists in Transylvania, who asserted distinct but overlapping connections to landscapes within Transylvania (White Reference White2000, 70f, 119f; Mitu Reference Mitu2014, 10–13). Sigerus, for example, freely recognized Hungarian nationalist claims to the Szeklerland (e.g. Figure 7) and the Kalotaszeg Valley (Figures 3, 6) as key sites of Hungarian culture, and Romanian nationalist claims to the Hatszeg Valley and surrounding mountains for its vibrant Romanian folk culture (e.g. Figure 8). Few Saxons had settled in these regions, which correspondingly played little role in Saxon nationalist attachment to territory. Rather, Sigerus identified the two principal territories of the former Natio Saxones as Saxon: the Königsboden [Crownland] in South Transylvania (e.g. Figures 1, 4, 5, 9) and the Nösnerland in North Transylvania. Sigerus identified no places with the Roma, whom non-Romani descriptions continued to present as a shiftless, vagabond people with no link to territory despite their overwhelmingly sedentary lifestyle (Davis Reference Davis2017). The two processes – of branding territories nationally and of illustrating those territories with photographs of nationally labeled landscapes, architecture, and peasant types – were mutually self-reinforcing, emphasizing nationalist connections to landscape and place.

Figure 8. F. Berger, “Romanian Shepherd in the Mountains” (top) and Dr. Büttner, “Romanian Shepherd’s Hut” (bottom). Public Domain.

Nationalists reinforced their claims through naming conventions. Geographical locations in Transylvania, as elsewhere in the Habsburg Empire, had multiple names reflecting the different languages of the Empire’s inhabitants. Labeling a photograph in a particular language could imply a territorial claim (Almasy Reference Almasy2018, 44). Sigerus applied German names to landscapes in the German version of Durch Siebenbürgen. However, the same locations were labeled in Hungarian and Romanian in the respective language editions; indeed, the photographic prints from these were overprinted with German placenames when cannibalized for the 1917 edition (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1917, 3). Instead, Sigerus expressed his assertions of a Saxon claim to south Transylvania more subtly, through his use of the ethnically clear term Sachsenland (Saxonland) rather than the more commonly used Königsboden, which might not be recognizable to an international audience as asserting a national claim.

In branding regions, landscapes, and landmarks nationally, Sigerus imposed on the landscape a monoculturalism that was largely absent in Transylvania; almost all portions of Transylvania (with the comparative exception of the Szeklerland), and especially all large settlements, had ethnically diverse populations (Mitu Reference Mitu2014, 13). While recognizing Romanian and Hungarian national claims in territories of little importance to Saxon nationalists, Sigerus elided the fact that by 1930 Saxons constituted only forty three percent of the population of the Königsboden, while Romanians constituted a relative majority at forty four percent (Wagner Reference Wagner1976, 423). These representations were in keeping with other Saxon ethnographic descriptions, which tended to produce mono-culturally conceived landscapes despite their mixed inhabitants (Török Reference Török2017, 657). Appealing to a heightened wartime sense of shared Germanness during the First World War (Philippi Reference Philippi and Rothe1994, 80), Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1917, 5) particularly emphasized the specifically German character of the Sachsenland in the 1917 edition, asserting that visiting German soldiers “were above all always amazed by Germanness [Deutschtum] in southern Transylvania.” He reinforced this monocultural view by removing from later editions a photograph of Romanian peasants near Hermannstadt included in pre-war editions (“Romänische Bauern aus Hermannstadt,” in Sigerus Reference Sigerus1917).

In addition to considering the region’s folk culture, as well as its historic architecture, as key attractions to Transylvania, Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 5) also extolled natural landscapes, especially the Carpathian Mountains:

This mountain world cannot compete with the imposing Alps of Tyrol and Switzerland; but the great nature here still has its originality and the full charm of its virginity, which can hardly be found in those highly cultivated countries. Here there is sometimes lovely, sometimes wild romantic high mountain country with primeval thickets and giant trees; rocky heaps with no path leading through them and charming valleys where there are no hotels waiting for tourists. Nothing can be found here of the excessive luxury of a modern culture that often impairs the enjoyment of nature!

Such imaginings stood in direct contrast to pre-nineteenth century Saxon views of the mountains as places of wildness and savagery, and principally inhabited by Romanians as Naturvolk (Heitmann Reference Heitmann, Gündisch, Höpken and Cologne1998, 35–37).

The visual and textual descriptions of the Sachsenland and surrounding mountains also served a second purpose: to direct an increased share of tourists to Saxon regions. Sigerus had long fostered tourist interest in the Carpathians through his directorship of the SKV. The aforementioned lack of comforts notwithstanding, Sigerus also described, and sometimes provided photographs of, many of the spas and sanatoriums built to allow greater enjoyment of the mountains, and which he had already identified in previous travel writing as key tourist attractions (Bielz and Sigerus Reference Bielz and Sigerus1903b).

However, tourism in Transylvania was competitive on national lines; rivals of the SKV included the Magyarországi Kárpát Egyesület [Hungarian Carpathian Association] (1873–1939), and later the Romanian Fraţia Munteană [Mountain Brotherhood] (founded 1921) (Heltmann Reference Heltmann, Heltmann and Roth1990, 11, 19–20). The majority of tourist attractions Sigerus included in Durch Siebenbürgen were designed to draw travelers to “Saxon” centers, including towns like Hermannstadt as well as smaller settlements, such as to Heltau (Cisnădie, Nagydisznód) to see the fortified church (Figure 9). Other sites directly promoted the SVK’s activities, such as the SKV sanatorium “Hohe Rinne,” or could be reached by walking tracks developed by the SKV, such as the Szurduk (Surduc) Pass or Lake Bulea (Lacul Bâlea, Bilea-tó). Durch Siebenbürgen, then, aimed to foster Saxon economic interests through national branding that would attract foreign tourism above other parts of Transylvania.

Figure 9. Anonymous, “Fortified Church in Heltau.” Public Domain.

Sigerus also took the opportunity to further his own professional interests. Durch Siebenbürgen devoted considerably more space to the SKV Museum’s collections than to comparable Hungarian and Romanian museums (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1917, 8, 14; Sigerus Reference Sigerus1929, 8, 14).Footnote 8 Sigerus (Reference Sigerus1929, 6, 8–9) also took the opportunity to recommend several of his other publications to interested readers, including his own work on Saxon folk costume, but few works by other nationalists. He did not, for example, recommend Dimitrie Comşa’s (Reference Comşa1902) comparable work on Romanian folk costume, which Sigerus had himself reviewed in glowing terms (Negoescu Reference Negoescu2012, 98–99). Such intermixing of nationalism and economic self-interest was common amongst Saxon nationalists.Footnote 9

Thus, by selective branding of Transylvania and its inhabitants through his choice of images and text, Sigerus engaged in economic nationalism, directing tourists to the benefit of the Saxon community (and himself). Such descriptions and images could be influential; German language publications like Durch Siebenbürgen had a greater international influence than Hungarian and Romanian publications. Consequently, international travel guides covered sites of Saxon national significance more extensively than other parts of Transylvania (Török Reference Török2017, 653–656). The various editions of Durch Siebenbürgen were drawn upon (and their illustrations often reproduced) by authors writing for a wider German-speaking audience, publishing in Transylvania, Germany, and Austria (Roth Reference Roth1908, 104, 109; Gegenbauer Reference Gegenbauer1914, 20; Müller-Langenthal ca. Reference Müller-Langenthal1922, 43, 131, 141; Huß Reference Huß and Stepan1922, 37, 39).

Conclusion

The publication of Durch Siebenbürgen was the result of the confluence of a number of trends. These included technical developments in photographic and printing technology, the expansion of the railway to Transylvania, and growing interest in travel to “unspoiled” landscapes. These opportunities engendered the founding of Saxon tourist organizations to exploit a growing tourist market. Such organizations took advantage of a relatively tolerant political environment following the 1890 agreement between the DSVP and the Hungarian government. These were opportunities that Sigerus, an active scholar of Transylvanian ethnography, and a leading figure in the Saxon tourism industry, with a history of successful scholarly tourist publications, was well positioned to exploit.

Sigerus asserted consistent messages through Durch Siebenbürgen. The first of these was a marketing campaign, branding Transylvania as a travel destination, inviting travelers to see its picturesque landscapes and settlements, folklore, and people – and, of course, to spend their currency. The second was an equally strident message of nationalist competition. This competition was not explicit in individual photographs; like most tourist images, they show no sign of social tensions or conflict. Rather, through his focus on the core Saxon-imagined landscapes, Sigerus not only directed tourism to benefit Saxon economic interests, but also asserted an idealized hierarchical social order, one increasingly undermined by the economic and political transformations of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In this order, Saxons were entitled to exert domination over “their” towns, and the wealth of the Saxon peasantry was the natural product of their civilizational standing and moral character rather than historical accident, just as Romanian and Romani poverty was the charming consequence of their closeness to nature. It was a social order in which each ethnicity accepted the natural – and separate – order of things, as demonstrated through the “objective” lens of the camera. This consistent nationalist message, directed at foreign and domestic audiences alike, goes a long way to explaining why the Hungarian and Romanian translations of Durch Siebenbürgen sold so poorly compared to the German editions.

Through Durch Siebenbürgen, then, Sigerus demonstrated a remarkable ability to brand nation and place, without state support, and in competition with other nationalists in Transylvania. That competition and broader nationalist contestation in the Habsburg Empire underlines that Sigerus was far from alone in his efforts. Individually and taken as a whole, the nineteenth century photographs available on postcards, in books, and in archives do offer a wealth of anthropological information. However, study of their historical colligation and labeling as in works like Durch Siebenbürgen provides deeper readings of their intended socio-political message.

Acknowledgements

This paper was originally presented at the “Visual Culture and Conflict in Central and Eastern Europe” symposium jointly hosted by the Centre for the Study of Violence, University of Newcastle (Australia), and Antipodean East European Study Group on June 18–19, 2018. My thanks to Alexander Maxwell, Roger Markwick, Han Lukas Keiser, Anna Davis, and the anonymous reviewers for their generous feedback.

Disclosures

None.

List of Images

Photographs are from the 4th edition of Durch Siebenbürgen (Sigerus Reference Sigerus1929), in the author’s private collection. While Sigerus does not acknowledge the photographers in the 4th edition, some were identifiable from earlier editions or other contexts. All reasonable efforts have been made to identify the photographer and confirm the public domain status of the images reproduced here.