On September 27, 1922, a group of wealthy Americans gathered at Faneuil Hall in Boston to launch a crusade for the defense of liberty, constitutional rights, and local self-government. Those gathered, an assembly of prominent businessmen and lawyers, disaffected Republicans and Democrats, and disappointed former antisuffrage activists, raised a toast to the founding of the Sentinels of the Republic. Self-consciously fashioning themselves as the direct descendants of the American revolutionary tradition, the Sentinels sounded a “call to arms” among the people about a new form of tyranny that threatened their liberty: “federal paternalism.” Formed in the wake of the Red Scare, the Sentinels affirmed that only a return to the “fundamental principles” of the Constitution would safeguard the republic from the threats of socialism, communism, and radicalism. The Sentinels were particularly alarmed and embittered by the adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, granting the federal government the power to prohibit the sale of alcohol, and the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, granting women suffrage. In 1924, when Congress submitted the federal Child Labor Amendment to the states for ratification, the Sentinels identified a very firm target for their first major battle. The proposed Twentieth Amendment would allow the federal government to regulate child labor, and the Sentinels waged war against it. The “‘so-called’ Child Labor Amendment,” the Sentinels charged, would “take away the sovereign rights of the states and destroy local self-government” by subjecting “your children and your home to inspection of a federal agent.”Footnote 1

Between 1924 and 1937, the Sentinels of the Republic led two successful campaigns against the adoption of the federal Child Labor Amendment by casting the amendment as a threat to the sovereignty of the home. A forerunner to the American Liberty League, the Sentinels were never much more than a small outfit of elite businessmen, lawyers, and politicians. Nonetheless, the organization's cozy relationships with industry and politics, the deep pockets of its backers, and in particular its ability to forge broad-based antistatist coalitions based on patriarchal ideas about the family made the Sentinels a political force. In 1924, they pulled off an upset victory in Massachusetts after the state's legislature referred the amendment to a people's advisory referendum. Bringing together a coalition of farmers, antifeminists, Boston Brahmins, the Catholic Church, old-stock Republicans, and ethnic Democrats under the banner of the “Citizen's Committee for the Protection of the Home and Child,” the Sentinels’ victory at the Massachusetts polls turned the tide against the amendment nationally in the 1920s. By 1925, thirty-four more states had voted to reject the amendment.

The onset of the Great Depression and election of President Roosevelt in 1932, however, revived the momentum to ratify the amendment. In 1934, the Sentinels formed a “National Committee for the Protection of the Child, Family, School and Church,” operating out of an outpost in St. Louis, Missouri, to lobby against it once again. The Sentinels leveraged their connections with the American Bar Association, the Catholic Church, prominent Protestant leaders and public figures, and industry to present a unified message about the dangers the amendment posed to the rights of both family and state government. While the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act included provisions regulating industrial child labor, the federal Child Labor Amendment remained ten states short of the majority needed for ratification.

The Sentinels’ crusade against the federal Child Labor Amendment reveals intimate connections between the economic and cultural roots of free-market conservatism. To the Sentinels, the amendment epitomized the threat of “federal paternalism” because it proposed to grant the federal government unprecedented powers over both industry and the family. Studying the politics and organizing strategies of the Sentinels also connects two separate stories about conservative activism in the 1920s and the 1930s. In the first story, as historians of gender and the Red Scare, especially Kim Nielsen and Kristen Delegard, have shown, the mixed-sex Sentinels composed part of a tapestry of 1920s conservative activists, led by female antifeminists, who forged an antiradical politics based on the defense of the white patriarchal family.Footnote 2 In the second, as told by George Wolfskill, Robert Burk, and Marjorie Kornhauser, the Sentinels reappear in the 1930s as part of the nucleus of interlocking antistatist groups of elite businessmen, led by the American Liberty League, who attacked the New Deal.Footnote 3 But throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, the ideology of the Sentinels remained consistent; they viewed the expansion of the federal government as destructive to the “private initiative” of men in both the patriarchal family and private industry. What changed in the years between was simply the type of “paternalistic” legislation that the federal government pursued, from the maternalist policies of the Children's Bureau to the economic relief programs of the New Deal.Footnote 4

The influence of the Sentinels therefore exposes the importance of gendered ideas about the sovereignty of the male-headed family to both the ideological and organizational development of free-market politics. Recent histories on the long roots of free-market conservatism have traced its origins to the antiregulatory agenda of businessmen in the 1930s.Footnote 5 Yet the roles of gender and the traditional family have been almost all but absent in those accounts.Footnote 6 Existing interpretations therefore overlook the galvanizing role that patriarchal ideas played in propelling economic elites into antistatist activism.Footnote 7 The Sentinels of the Republic firmly believed that the male-headed family constituted the most local level of self-government, and deployed ideas about the sovereignty of the family to stitch together broad antistatist coalitions across sex, class, and faith lines.

While historians acknowledge that anti-New Deal lobbies generally failed to make much headway in selling free-market politics during the 1930s, the Sentinels successfully sold an antistatist agenda in their campaign against the Child Labor Amendment. Fusing the causes of free industry and the freedom of the family, the Sentinels brought together businessmen, conservative lawyers, antifeminists, anticommunists, and conservative Catholics and Protestants in an alliance that foreshadowed the political alignment of the New Right by nearly half a century. Indeed, the Sentinels’ campaign against the Child Labor Amendment reveals new ties between religious conservatism and free-market conservatism, and points to a longer history of alliances between conservative religious groups and business interests––alliances that coalesced around questions of gender and the family.Footnote 8

The Origins and Ideology of the Sentinels

The Sentinels of the Republic formed in the summer of 1922 to consolidate and reformulate conservative efforts to resist the expansion of the federal government after the ratification of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments. The founding members of the Sentinels, all wealthy, native-born white Protestants, included prominent men and women who had led the fight against Prohibition and women's suffrage in single-sex organizations such as the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, the Maryland League for State Defense, and the Constitutional League of Massachusetts.Footnote 9 The Sentinels sought to channel the single-sex, single-issue conservative activism of the 1910s into a mixed-sex, pan-conservative movement dedicated to a broader fight against centralization. The proliferation of federal bureaucracies and the growth of federal power that had marked the Progressive Era, the Sentinels warned, would continue to pervade President Warren Harding's administration unless checked by the citizen's watchful eye.Footnote 10 The group's fears about the dangers of “federal paternalism” were heightened by the Red Scare, a widespread panic of a creeping red menace triggered by a series of anarchist bombings on U.S. soil in 1919 in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. For the Sentinels, the centralization of federal government powers demonstrated the insidious influence of both an internal and external communist threat.Footnote 11 In that context, they viewed federal paternalism as the “third crisis” facing the nation, charging that it behooved the “patriots of America” to rise up again “to battle for the preservation of constitutional government, the cornerstone of American liberty” that the patriots of 1776 and 1861 “built and cemented with their blood.”Footnote 12

The Sentinels fell far short of their stated goal of building a mass movement that would bring together all patriotic conservatives in the United States. After absorbing a few existing conservative groups into their ranks, the Sentinels announced the lofty goal of attracting a “million patriots” who would pledge to maintain “the fundamental principles of the constitution” of individual liberty, states’ rights, and local self-government.Footnote 13 The Sentinels set about establishing “Committees of Correspondence” across the country, modeled on the shadow governments of the thirteen British colonies that had declared independence during the American Revolution. By 1923, the group claimed to have branches in more than 43 states and 480 cities and towns.Footnote 14 The leadership of the Sentinels, predominantly Northeast “wet” (anti-Prohibition) Republicans and converts to the states’ rights cause, did succeed in enlisting a number of Southern Democrats.Footnote 15 Nonetheless, the membership base remained piddling. Membership peaked at around 9,000 in the late 1920s after the Sentinels doubled its numbers at the height of the 1924–1925 antiratification campaign.Footnote 16 In the 1930s, as anti-New Deal organizations proliferated and discussions on merging with the newly founded American Liberty League fell through, the Sentinels’ membership base dwindled to around 3,000.Footnote 17

Notwithstanding the organization's opposition to highly centralized power, the Sentinels built its influence primarily through its executive committee, which was composed of around forty to fifty wealthy businessmen, elite lawyers, antifeminist activists, religious leaders, conservative politicians, and public figures. In building that core committee, the leaders held true to their founding promise that the Sentinels of the Republic knew “no sex, no party, no creed.”Footnote 18 Instead, what bound what bound the organization together was a common class background and shared aversion to the political developments of the Progressive Era—namely the enlarged role of federal government in public life driven primarily by female reformers and typified by the enfranchisement of women in the 1920s. Made up primarily of the patrician class of old-stock Northern Republicans, the key players on the Sentinels’ executive committee represented the overlapping interests of pro-business, antifeminist, antistatist, and religious conservatives who viewed the expansion of federal power as a fundamental threat to the nation.Footnote 19 The convergence of these interests shaped the ideology of the Sentinels that viewed “federal paternalism” as a threat to the independence of self-governing men.

The Sentinels' inaugural president, Louis A. Coolidge, was a Boston Brahmin who traced his lineage back to Mary Chilton, the first person said to have set foot on Plymouth Rock. After graduating from Harvard, he worked in Washington, DC, between 1890 and 1909 as a political correspondent, private secretary to Republican senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and, later, assistant secretary of the treasury in Theodore Roosevelt's administration. Returning to Boston in 1909, Coolidge became the director of the United Shoe Manufacturing Company. Coolidge's antipathy to government intervention in industry hardened sharply during World War I, when he resigned from the Shipbuilding Labor Adjustment Board, a voluntary partnership between business, labor, and government set up to resolve strikes over wages. Remaining disenchanted with Republican politics, but also active in anti-Prohibition campaigns in the 1910s Coolidge personified the relationship between business and politics the Sentinels sought to foster. Explaining his view in 1924 that “every businessman should be a politician, every politician a businessman,” Coolidge's fears about federal paternalism were far from allayed by the Republican deregulatory economic agenda of the 1920s. He urged businessmen to keep a closer eye on the expansion of federal government power.Footnote 20

Lawyers and antifeminist activists also featured prominently in the Sentinels’ leadership. After Coolidge died in May 1925, Bentley Warren, a Boston railway attorney and active Democrat, briefly assumed the leadership, and Alexander Lincoln, the former Massachusetts assistant attorney general, took the helm from 1927 to 1936. While the prominence of lawyers, Democrat and Republican in equal proportion, helped to explain the Sentinels’ fixation on the Constitution as the instrument for achieving limited government, the outsized contribution of former antisuffragists and antiradical activists pointed to the importance of antifeminist ideas to the Sentinels’ ideology. Most notably, Katharine T. Balch, the former president of the Women's Anti-Suffrage Association of Massachusetts, served continuously as the Sentinels’ secretary, leading the organization to establish their headquarters in Milton, Massachusetts, where Balch was based.Footnote 21 Thomas F. Cadwalader, the chairman of the Sentinels’ executive committee, reflected the overlapping interests of the two groups. A Democratic attorney from Baltimore, Maryland, Cadwalader had helped file an unsuccessful challenge to the Nineteenth Amendment in 1922.Footnote 22

Conservative ideologues such as Nicholas Murray Butler and Reverend J. Gresham Machen sat on the executive committee, and publicly augmented the tight web of businessmen, lawyers, and antifeminists at the core of the Sentinels’ leadership. Butler, the outspoken president of Columbia University, hailed from a middle-class Presbyterian New Jersey family, embraced Episcopalianism as he rose up the ranks of New York's high society and Republican politics, and injected himself into international politics in the 1920s. Despite his more modest roots, as the socialist (and a former student of Butler's) Upton Sinclair charged, Butler “considered himself the intellectual leader of the American plutocracy,” making him the ideal public spokesmen for the Sentinels’ platform. Machen, a theologian at Princeton Theological Seminary, enlisted as a Sentinel in 1924, impressed by the group's antiratification campaign. Machen was a towering, if controversial, figure in fundamentalist circles, credited with leading the revolt against modernism. However, he deviated from most fundamentalist Protestants in the 1920s who strongly supported Prohibition. In his opposition to Prohibition and the establishment of a federal education department, he sympathized instead with the more antistatist politics of the Sentinels.Footnote 23

The Sentinels’ opposition to federal intervention in family life was critical both to their formation and to their disproportionate influence as an antistatist lobby group in the 1920s and 1930s. As historians of antisuffragists have demonstrated, opponents of women's suffrage, especially male antisuffragists, held fast to a conception of the white male head of the household as the “individual” who governed and represented his family.Footnote 24 The Sentinels were one of a number of antiradical groups that carried that ideology into the post-suffrage era as part of a conservative opposition to social welfare programs.Footnote 25 Throughout the 1920s, the Sentinels limited their campaigns to attacking a suite of maternalist projects that would have extended the role of the federal government in family life; they opposed the nationalization of marriage and divorce laws, a federal department of education, the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act, and the Equal Rights Amendment. Indeed, while the Sentinels privately reviled the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, they waited until 1931, when the movement to repeal Prohibition had gained sufficient force, to officially register their support.Footnote 26 Since its founding, a representative of the Sentinels reflected in the 1930s, the organization had been “engaged in an almost continuous contest with the Children's Bureau and its allies.”Footnote 27 As Kim Nielsen has explored, while historians generally regard the policies emanating from the Children's Bureau as the product of maternalist politics, the Sentinels’ and their allies’ denunciations of “federal paternalism” were not a slip in language. They underscored the importance of the “politicization of patriarchal fatherhood” to their opposition.Footnote 28 The Sentinels’ objection to maternalist programs was the entry point for the group's consistent opposition to federal aid programs, higher taxes, and government regulation of industry that carried into the New Deal era.

A widespread conservative cultural consensus about the importance of the sovereign, white, male-headed family propelled the Sentinels’ efforts. They deployed the techniques of modern lobbying, running targeted campaigns that used print media, national radio, and experimentation with film to sell an antistatist agenda to the public at large.Footnote 29 In an era when the lines between liberal and conservative politics were more fluid, especially with regard to the family, the Sentinels used media appeals to reach broad cross-sections of the public without ever building a mass membership base.Footnote 30 Though the Sentinels had opposed the Nineteenth Amendment, for example, they assiduously courted women—well understanding that the newly expanded electorate had doubled in size—by elevating appeals to the home and family in their antistatist campaigns.Footnote 31 The group benefited from crucial injections of corporate and manufacturing money at key moments, most notably during its antiratification campaign in 1924 and anti-New Deal campaign in 1934, but otherwise survived on a skeletal budget. Always a small outfit whose views about state intervention remained to the right of even the Republican Party the Sentinels nonetheless profited from the broader milieu of conservative Protestant movements in the 1920s that professed to defend the white, patriarchal family.

While the Sentinels stood apart from most of its conservative compatriots by mobilizing the politics of the family in the service of an antistatist and antiregulatory agenda, the rallying cry of the “sanctity of the home” reverberated widely in the political culture of the 1920s. Defenses of the white patriarchal family fanned the flames of antiradical activism, drew millions of American men and women into the ranks of the second Ku Klux Klan, and animated support for Prohibition.Footnote 32 Indeed, family protection had long animated more state-centered and progressive campaigns such as the movements for temperance and Prohibition.Footnote 33 Since the late nineteenth century, the Women's Christian Temperance Union had mobilized a mass movement of women around the banner of “home protection.” At the 1924 Democratic National Convention, William Jennings Bryan lit a fiery defense of Prohibition and claimed to lead the “defenders of the home” against the wet Al Smith.Footnote 34 In the 1920s, organizations such as the Klan sought to shore up the boundaries of a white Christian nation through state power, advocating for Prohibition and strong federal and state control over public schooling in pursuit of an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, and anticommunist agenda.Footnote 35 By contrast, the Sentinels argued that any expansion of federal government power imperiled the sovereignty of the white, male-headed family.Footnote 36

Unlike other conservative Protestant organizations of the era, the Sentinels also avoided overtly nativist positions and forged close partnerships with leading conservative Catholics. While the Sentinels privately supported “Americanization” and remained suspect of “subversive influences,” the executive committee avoided taking a public position on such questions.Footnote 37 To be sure, many Sentinels had formerly been part of the Massachusetts Immigration Restriction League, but Butler opposed highly restrictive immigration laws because of their potential economic impact––a view likely shared by other Sentinels with interests in manufacturing.Footnote 38 Mobilizing public opinion against the Child Labor Amendment, especially in places like Massachusetts where the Sentinels acknowledged the heterogeneity of the population and the importance of winning over ethnic and immigrant workers, would have been difficult with nativist positions.Footnote 39 The limits of their ethnic and religious tolerance, however, were exposed during Congressional hearings into anti-administration lobby groups in the 1930s, when the Sentinels were censured and widely discredited for the anti-Semitic pronouncements of its president, Alexander Lincoln.Footnote 40

Additionally, while many conservatives in the 1920s relied on religious fundamentalism as a fulcrum, the Sentinels instead championed a near-fundamental reverence for the U.S. Constitution as a bulwark against social change and communism. They vowed to honor the “original intent of the framers” and maintain the “fundamental principles” of the Constitution by opposing federal amendments, legislation, and bureaucratic agencies that “encroached on the reserved rights of the States and the individual citizen.”Footnote 41 Here the Sentinels anticipated the language of the American Liberty League, whose stated founding aim in 1934 was to “defend and uphold the Constitution,” espousing what Jared Goldstein has aptly described as “constitutional nationalism” and a “political analog to originalism.”Footnote 42 Like the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, a parallel 1920s organization, the Sentinels wrestled with something of a paradox regarding recent constitutional amendments as “betrayal[s]” that were “destructive” to the true purposes of the Constitution.Footnote 43 Indeed, there was a certain irony in their historical reading of the Constitution––whereas their forbearers in the early republic had aligned with the Federalist party and championed a strong national administration to protect their financial and class dominance, by the early twentieth century, the aristocratic elite behind the Sentinels channeled more Jeffersonian ideals of radically decentralized government towards the same end.Footnote 44 The Sentinels’ slogan—“Every citizen a Sentinel! Every home a sentry box!”—made clear the ideological relationship between the liberty of the individual and the freedom of the home.

The 1924 Campaign in Massachusetts

The federal Child Labor Amendment was first floated in Congress in June 1922. For its supporters, it represented the final resolution to a decade-long effort to grant the federal government the power to regulate child labor. Congress had passed two federal child labor laws: the Keating-Owen Act of 1916 prohibited the interstate trade of goods produced by children under fourteen years, and the “Child Labor Tax Law” of 1919 imposed a ten percent tax on the profits of companies that used industrial child labor. But the Supreme Court struck down both laws as an unconstitutional exercise of the interstate commerce clause and the taxing power in Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) and Drexel Furniture Co. v. Bailey (1922), respectively. The proposal for a constitutional amendment surfaced two days after Drexel was handed down. Twenty-five organizations, made up predominantly of labor unions and national women's organizations, formed a committee to draft it. In 1924, after two years of debate, the would-be Twentieth Amendment was introduced in Congress, proposing that the federal government “limit, regulate and prohibit the labor of persons under eighteen years of age.”Footnote 45

The broad scope of the amendment reflected both the optimism and anxiety of its backers. After decades of attempting to devise enforceable child labor laws, reformers set the age limit at eighteen, not sixteen, which then defined the end of childhood in the census, so that seventeen-year-olds in hazardous industrial occupations would not be beyond reach. The word “labor” as opposed to “employment” was adopted at the insistence of the National Child Labor Committee, who feared that parents would define the work their children performed in farms, homes, and tenements as “chores.”Footnote 46 The construction of the amendment also reflected the changing character of child labor. The 1920 census showed that the number of children employed between ages ten and fifteen had dropped from two million children as recorded in the 1910 census to just over one million.Footnote 47 As reformers complained, the 1920 census concealed the more accurate numbers of laboring children because it was taken during a brief period when the second national child labor law was in effect and in mid-January before any agricultural labor resumed. Nonetheless, the rates of industrial child labor, performed predominantly by white children, had declined, as reflected in the decision of the National Child Labor Committee in the early 1920s to turn its attention to agricultural labor for the first time.Footnote 48 The opponents of the amendment would interpret and exploit this broader framing to argue that it gave Congress the power to interfere with family farms, the domestic chores of teenagers, and the education of youth.

At the time, however, the amendment enjoyed a broad base of support. Over the past decade, four amendments had altered the Constitution to meet the governing needs of the day. Much to the Sentinels' chagrin, in 1922 Republican president Warren Harding urged Congress to adopt the Child Labor Amendment on just those grounds, arguing that the Constitution ought to be amended “to meet public demand when sanctioned by deliberate public opinion.”Footnote 49 In 1924, with the support of newly elected Republican president Calvin Coolidge, the amendment easily secured the necessary two-thirds majority in both houses, with the House of Representatives passing it by a vote of 297 to 69 and the Senate approving it shortly thereafter. Thirty-six states now needed to ratify it.Footnote 50

Numerous antiratification organizations cropped up around the country to campaign against the proposal, but, based in Boston, the Sentinels quickly found themselves at the frontline of the war.Footnote 51 Massachusetts was expected to be the first state to ratify the amendment, with the state's General Court moving to ratify the amendment on June 5. The Sentinels scored an early victory, however, when the last-minute intervention of Lincoln, who offered “sober second counsel,” led the General Court to instead refer the amendment to an advisory referendum to be held in conjunction with the state's election in November.Footnote 52 Later that month, the amendment squeaked through in Arkansas by one vote. Over the summer, Louisiana, Georgia, and North Carolina rejected the amendment, well representing both the Southern mill industry and a zealous Southern states’ rights tradition.

Much of the nation looked to Massachusetts, then, as the bellwether for the amendment's fate. The Sentinels knew the task of defeating the amendment would be a “formidable” one. “Public opinion, at the outset, moved by the appealing nature of the subject, was almost uniformly for the Amendment,” they admitted.Footnote 53 Considered a natural home for approval, the Bay State had led the nation in introducing child labor regulations and compulsory schooling laws since the mid-nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, the lax regulation in Southern industrial states supposedly disadvantaged Massachusetts's mills. The amendment had the support of Massachusetts's leading representatives, notwithstanding their small government leanings, including Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and David Walsh, along with U.S. president Calvin Coolidge. For these reasons, the supporters of the amendment actually assembled more slowly than its opponents. As the National Child Labor Committee conceded, they were “lulled to sleep, or at least into a state of semi-slumber,” because they “blundered in presuming” that because all of the politicians from Massachusetts had supported it, “the people would too.”Footnote 54

By contrast, after securing the advisory referendum, the Sentinels quickly swung into action, and, in line with state campaign laws, set up a campaign committee named the “Citizen's Committee to Protect Our Homes and Children.”Footnote 55 Sentinels president Louis Coolidge recruited Clifford Anderson, Associated Industry president, to finance the campaign. Coolidge himself took charge of the organizational strategy and public relations sides, employing the services of the Hunt-Luce advertising agency.Footnote 56 Throughout the campaign, the Sentinels vociferously denied that the Citizen's Committee was a mere front for industry. Coolidge and Cadwalader would go so far as to suggest the influence worked in the opposite direction. Coolidge feared the business community had “undermined its own freedom” in blithely accepting government aid.Footnote 57 Cadwalader argued that while farmers had previously held questionable economic views on the role of government, farmers’ associations were ripe for conversion to the Sentinels’ cause because they were filled with “patriotic minded men.”Footnote 58

So the Sentinels deliberately created a degree of distance between the manufacturing industry and its public facing campaign, emphasizing instead the dangers that the amendment posed to the family. The Citizen's Committee, chaired by Hebert Packer, a former Massachusetts attorney general, presented itself as a moderate, respectable, and impartial organization, boasting the names of prominent lawyers, statesman, religious leaders, and the presidents of Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Boston College. Speaking directly to parents, the committee urged: “If you would defend your hearthstone from centralized bureaucratic control … if you believe in local self-government, if you would preserve the foundation stones of democracy—vote NO on Referendum No. 7.”Footnote 59

The charge that the child labor regulations would invade parental rights and individual liberty were, of course, not new arguments. Since the late nineteenth century, conservatives and antistatist activists had fomented opposition to compulsory schooling, child labor, and mandatory vaccination laws at the local and state level by arguing that such legislative innovations overrode the natural and common law rights of fathers.Footnote 60 Indeed, as late as 1916, the sovereign rights of fathers figured prominently in the decision to grant an injunction against the first national child labor law. A federal court judge in North Carolina held that the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act exceeded the powers of Congress in regulating the internal labor conditions of the states and violated the economic rights of men. It was an enduring, timeless, natural right, the judge opined, beyond dispute, that in “the family government the father has the right to control of his children and the right to support by service of his children.”Footnote 61 The Sentinels updated this long-standing proprietary conception of fatherhood, as the proposed constitutional amendment shifted the political debate from whether the states possessed the right to regulate child labor to whether the federal government possessed it.

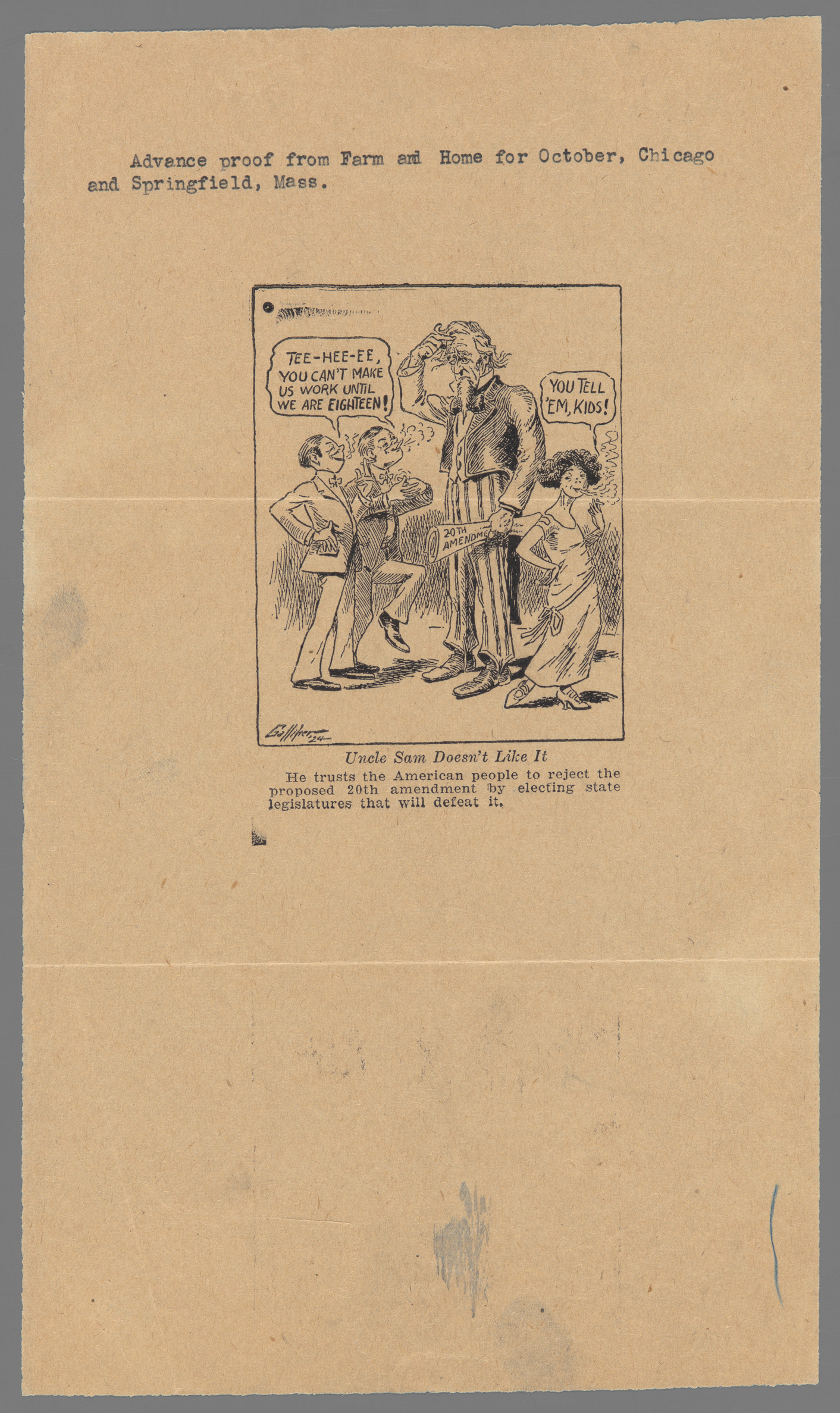

Capitalizing on the backlash to the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, the Sentinels cast the expansion of federal government power over children as yet another incursion on the rights of self-governing men.Footnote 62 George Stewart Brown, a Sentinel and lawyer from Baltimore, explained that the amendment threatened his “fundamental individual right” to decide whether his “seventeen year old” would work or go to school, or what kind of religious instruction he should receive. Brown, who had argued that women's suffrage was unconstitutional because it changed the composition of state electorates, declared that individual rights were the provenance of men who retained rights of governance over their children until eighteen years of age (Figure 1). Positioning family government as the most local form of self-government, Brown objected that the amendment “usurped” his rights, and, if adopted, would destroy his “precious right of local-self-government.”Footnote 63

Figure 1. Cartoon mocking the proposed Twentieth Amendment. Advance proof from the October 1924 issue of Farm and Home, a national farming magazine that coordinated with the Sentinels. Box 3, Folder 14, A109, Lincoln Papers. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

While the Sentinels held reservations about women's enfranchisement, they also needed to take advantage of the expanded voter base and to appeal to women's authority as mothers. Indeed, they viewed the enfranchisement of women as having created the conditions for the Child Labor Amendment as well as a critical part of the strategy for scotching it. As Warren explained, the whole mess of the Child Labor Amendment had come about because nothing appealed to women “more instinctively, more intuitively than the family.” Women's innate interest in domestic life, Warren reflected, often led to their political betrayal, because when it was suggested to women that “children need protection,” women were so blinded by maternal instinct and political inexperience that they assumed the only way to protect children was to change the Constitution. So the Sentinels needed to communicate in an “affirmative way” that they really stood for the “preservation of the family.”Footnote 64

Anti-ratification materials directly appealed to maternal authority. As Butler affirmed in a radio address, “No American mother would favor the adoption of the constitutional amendment which would empower Congress to invade the rights of parents and to shape family life.”Footnote 65 The Citizen's Committee disseminated a voter card that mocked the inability of a teenage son to step in as the breadwinner and save his widowed mother from the indignity of laboring for her family (Figure 2). Taking advantage of the expanded voter base, the Sentinels mixed appeals to men's individual rights as citizens with appeals to women's moral authority as mothers in a gendered discourse that converged around a defense of the sovereign home.

Figure 2. Citizen's Committee Voter Card, 1924. Box 3, Folder 14, A109, Lincoln Papers. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

The Sentinels rightly concluded that the politics of the family could cut across class, faith, and partisan lines to mobilize broad opposition to the amendment. While they waxed lyrical about states’ rights elsewhere, the antiratification materials in Massachusetts often drew a direct line between the expansion of congressional power and the diminishment of family government.Footnote 66 An oft-quoted statement from Reverend Warren Candler, a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Georgia, omitted states’ rights from the equation altogether: “This ‘Child Labor’ amendment proceeds on the absurd assumption that Congress will be more tenderly concerned for children than their own parents.” It was a troublesome assumption in the bishop's mind because “this assumption appraises congressional government far above its worth and puts home government far below its value.”Footnote 67 This savvy strategy not only downplayed arguments about states’ rights, but also diverted attention away from questions of economic regulation and even the morality of child labor itself. As the New Republic, a bastion of Progressivism and loyal friend of the amendment, explained in 1924, “In the current propaganda against the Child Labor Amendment, the economics of the issue are strangely subordinated. We are gravely assured … that what is at stake is our sacred liberty, the sanctity of our homes.”Footnote 68 Reformers, of course, were deeply frustrated by the argument that the amendment would invade individual rights and the home. The amendment did not grant Congress any powers that states had not already relied upon. Its supporters struck back at this misrepresentation. But it mattered little; what mattered were the rights that the citizens imagined were under threat, and these included the “natural rights” of parents.

By painting the amendment as a threat to the sovereignty of the home, the Sentinels predicted that they would be able to motivate diverse sectors of the community to go to the polls to vote it down. They linked the causes of federalism and “fundamental” parental rights, and deftly bundled together the interests of mill owners, farming families, and working-class families. In this frame, the amendment also threatened the political and cultural interests of middle-class families and religious minorities. In the Massachusetts referendum, the Sentinels were therefore able to quickly forge important coalitions between existing organizations and institutions with significant clout within the state.

They started first with the Catholic Church. While the Sentinels’ own leadership ranks brimmed with Boston Brahmins, they secured the support of Cardinal William O'Connell, the archbishop of Boston. O'Connell's decision to speak out against the federal Child Labor Amendment was no sure bet. Before the 1920s, O'Connell had held to the official church position to keep out of politics, refusing to reveal his personal political positions on partisan questions or women's suffrage.Footnote 69 But both the pro- and antiratification campaigns were keen to secure the archbishop's support. The proratification committee met with O'Connell in September and felt confident it had swayed him.Footnote 70 Amid the resurgence of anti-Catholicism in the 1920s, however, the Child Labor Amendment was one of numerous proposals that potentially threatened Catholic interests, with long-standing tensions over state and parochial schooling reaching a boiling point as the proposal for a federal education department reached the floor in Congress.Footnote 71 When O'Connell made his decision in early October, he concurred with the Sentinels’ argument that the amendment would give Congress unlimited powers over the education and labor of children, constituting an “unprecedented threat to the natural rights of parents.”Footnote 72 After O'Connell made his stance public, James Curley, the Irish Catholic mayor of Boston, promptly rescinded his support for the amendment. By late October, the Sentinels’ Citizen's Committee contained the names of both O'Connell and Curley.Footnote 73

Cardinal O'Connell made use of the Catholic Church's extensive institutional reach within Boston to motivate voter turnout against the amendment. Throughout the month of October, the pages of the diocesan paper the Pilot were filled with discussions of the amendment. The cardinal urged the clergy of Boston to dedicate their sermons to warning the parishioners of the dangers of the amendment. He further encouraged lay Catholics to organize against the amendment by targeting female parishioners. O'Connell invited over 600 Catholic women, representing Boston's 300 parishes, to meet with him on October 6, 1924, one month prior to the referendum, to hear a host of speakers led by Frances Slattery, the president of the League of Catholic Women.Footnote 74

Slattery, an enlisted Sentinel and member of the Citizen's Committee, threw herself behind the anti-ratification campaign. A devout Catholic, she claimed that the Sentinels were the “only organization” outside the church deserving of her affiliation because the Sentinels’ campaign transcended politics in defense of the “moral cause” of the family. After the election, Slattery bragged before a meeting of the Sentinels that she had registered 162,000 women to vote in fewer than ten days. Warren praised her contribution, noting that, if women in other churches did the same work, the Nineteenth Amendment could be judged to have greatly increased the “safety of the nation.”Footnote 75 While Slattery may have exaggerated her role, the Sentinels undoubtedly benefited from the church's influence among Boston's large working- and middle-class Irish Catholic population.

The Sentinels also convinced Protestant leaders to take positions against the amendment, appealing to common Catholic and Protestant beliefs about the autonomy and hierarchy of the family. The Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts, William Lawrence, joined O'Connell in lending his name to the distinguished citizens who supported the Citizen's Committee. Reverend Joseph Shepler, the presiding elder over 59 Methodist churches, also came out against the amendment.Footnote 76 In a radio address broadcasted on October 10, Coolidge himself appealed to the “Christian men and women of Massachusetts” to “carefully and prayerfully” study the amendment. He painted a domestic scene of a family gathered around the hearth with “benediction of a home-loving Christian mother.” The children, he described, were “flushed and happy” from the “wholesome labor” they had completed around the house and farm on return from school.Footnote 77 The Child Labor Amendment threatened that scene—the home life of respectable, middle- and upper-class families along with the working-class families whose children labored in factories and mills.

The Sentinels enlisted the help of antisuffragists, who still held some influence in the state. Boston had been a hotbed of antisuffrage activism in the early twentieth century, reflected in the membership of the Women's Anti-Suffrage Association of Massachusetts, which reached 40,000 women in 1917.Footnote 78 While broad-based antisuffrage activism receded quickly after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, a committed core of Northeastern antisuffrage (turned antifeminist and antiradical) activists might have lost the war but were determined to win the peace. A group of five women, including Sentinels secretary Balch, consolidated their efforts in the Woman Patriot Publishing Company, based in Washington, DC, refitting their antisuffrage newspaper the Woman Patriot to this new purpose, with the updated byline “Dedicated to the Defence of the Family and the State AGAINST Feminism and Socialism.”Footnote 79 Fanning the flames of antiradicalism, they doused the pages of the Woman Patriot from May through November with redbaiting appeals, fixating on the friendship between Florence Kelley, a key backer of the amendment, and Frederick Engels as proof that a “socialist dictated the draft of the amendment” and charging that an “interlocking” web of radical women at the Children's Bureau now intended to “organize a revolution through women and children.”Footnote 80 While the circulation of the Woman Patriot had shrunk to around 3,000 in the early 1920s, its pages provided plenty of ammunition to alarm anticommunists and antiradicals of the subversive nature of the amendment.Footnote 81

The final weapon in the Sentinels’ arsenal was the claim that the amendment would place a federal agent on every farm in the country—an appeal that goaded both farmers and middle-class urbanites who held romantic ideas about the white farm child. By the 1920s, most Americans, and even most mill owners, would have conceded that industrial labor injured the health and development of young children. But in a moment when the U.S. population became predominantly urban instead of rural, many Americans valued farm work for precisely the opposite––the fresh air of the farm was the perfect laboratory for developing healthy bodies and healthy minds, instilling children with skills and a sense of responsibility for the family economy. Another Citizen's Committee voter card pictured the popular antiratification argument that the amendment would prevent healthy, white teenage sons from helping out independent farmers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Citizen's Committee Voter Card, 1924. Box 3, Folder 14, A109, Lincoln Papers. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

The Sentinels coordinated with the conservative newspaper editor of the Springfield Union and with the Phelps Company, which published the weekly New England Homestead and monthly national Farm and Home newspapers, all based in Springfield in the west of the state, to pump out antiratification materials.Footnote 82 In the lead-up to the Massachusetts referendum, the American Farm Bureau Federation voted to oppose the amendment, with its news services heavily circulating antiratification materials thereafter.Footnote 83 While the Sentinels would claim credit for having a “great deal to do with setting the farm organizations right” on the amendment, they were one of a number of manufacturing interest groups clambering to sway farm groups (if the economic self-interest of commercial agriculture had not led them to oppose the amendment already).Footnote 84 Nonetheless, sensing how the farm propaganda was playing out in anti-ratification campaigns, the National Child Labor Committee suspended its investigations into the conditions of agricultural child labor in 1924.Footnote 85

On November 4, 1924, the voters of Massachusetts rejected the proposed Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution 697,563 votes to 241,461. The defeat in Massachusetts precipitated a swift and sharp turn in public opinion and political will. In New York, another state considered a reliable stalwart by amendment advocates, Governor Al Smith, who had supported the amendment, immediately flinched, suggesting that an advisory referendum be held there as well.Footnote 86 In December, the Sentinels held a meeting in Philadelphia of sixteen antiratification groups, putting itself forward to lead the nationwide campaign against ratification as manufacturing groups, farm bureaus, and patriotic organizations flooded other states with the antiratification appeals the Sentinels had honed in Massachusetts.Footnote 87 Like dominoes, the support of Northeast, Midwest, and Western states fell. By the summer of 1925, only three more states, Arizona, California, and Wisconsin, had ratified, while a total of thirty-four states in quick succession voted against its adoption.

In the aftermath of the election, the supporters of the amendment complained that they had been defeated by a deliberately deceitful campaign financed by the manufacturing industry. Indeed, the Citizen's Committee had outspent the proratification committee in Massachusetts by a ratio of five to one.Footnote 88 Lincoln strongly denied the charge that the National Association of Manufacturers had financed the campaign. Anderson, however, was also a member of the National Association of Manufacturing's antiratification committee, which had circulated strikingly similar materials. Lincoln pointed to the high caliber of upstanding men and women who formed the Citizen's Committee as proof of its impartiality, alleging that the $15,000 spent by the committee had been raised by donations, none of which exceeded $200, from concerned citizens.Footnote 89

In truth, the prominent members of Boston's high society, whom Lincoln held up as examples of the Sentinels’ impartiality, actually revealed a Citizen's Committee awash in manufacturing money. Lincoln singled out Elizabeth Lowell Putnam, for example, a matriarch of a Boston Brahmin family and a formidable antisuffragist. Lowell Putnam styled herself an expert on maternal and infant health, but she was also an heir to the Lowell textile fortune her father had amassed from owning Pacific Mills, the largest combine of its era. She was also related to two of the other prominent “disinterested” members of the committee; her brother was Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the president of Harvard University, and their first cousin, the Episcopal Bishop William Lawrence, had grown up in the neighboring town of Lawrence, where his father owned Ipswich Mills.Footnote 90 After the Supreme Court struck down the first child labor law in 1918, a number of Massachusetts mills had also extended their operations in the South and invested in new mills there.Footnote 91

Nonetheless there existed an ideological coherence among the prominent backers of the Citizen's Committee that coalesced around the private property rights of men and limited government.Footnote 92 As Coolidge explained, after quitting his role at the United Shoe Manufacturing Company to dedicate himself full-time to the antiratification fight, he opposed all forms of “government ownership, no matter what its guise may be.”Footnote 93 Long before joining the Citizen's Committee, Bishop Lawrence was renowned for preaching about the compatibility of laissez-faire capitalism and Christianity, while Cardinal O'Connell was a conservative force within the Catholic Church, lecturing on the importance of “limited state activity.”Footnote 94 After the Massachusetts campaign, Lowell Putnam remained steadfast in her antisuffrage convictions about the importance of male-headed family government, joining the Sentinels in Congress in opposing the nationalization of marriage and divorce laws and the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act.Footnote 95 Just as social reformers such as Florence Kelley had long viewed protective labor laws for women and children as an opening wedge for the protection of all laborers, the Sentinels viewed the “nationalization” of children under the Child Labor Amendment as the opening wedge for federal control of industry, religion, and education.Footnote 96 As Reverend Machen put it, “If we give the bureaucrats our children, we may as well give them everything else.”Footnote 97

Moreover, their arguments about the Child Labor Amendment had enabled the Sentinels to build a broad-based antistatist coalition. Machen publicly struck back at the idea that the Sentinels’ success could be reduced to the propaganda of “fat business men and windy professors who prate about the sacredness of the home.” Instead, he charged that the explanation for the defeat was much simpler: the American people had become increasingly “disgusted” with the tendency to place “intimate details of family life in the hands of a centralized Washington bureaucracy.”Footnote 98 There was much to Machen's assessment that a wide range of Americans found themselves politically invested in the sovereignty of the home. This fact had allowed the Sentinels to forge common ground among unlikely allies, using churches and public figures to transcend traditional political divides. The head of the Massachusetts ratification committee, Dorothy Kirchwey Brown, conceded that the “combination of reactionary Yankee Republicans and reactionary Irish Democrats” who rallied to the Sentinels' cause was insurmountable. While the antiratification campaign remained virtually silent on the interests of industry, it still primed the public to view state intervention as a dangerous and destructive force.

Indeed, in the campaign in Massachusetts, the Sentinels of the Republic had found an effective way to fight the expansion of the state—one that undergirded its lobbying efforts for the rest of the 1920s and also prevented the ratification of the same amendment in the 1930s. Between 1922 and 1929, the Sentinels joined forces with the National Catholic Welfare Council to defeat repeated proposals to establish a federal department of education.Footnote 99 In 1926, they appeared again in Congress to broker the repeal of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act, which had provided federal funds to states for prenatal and children's health services on a matching basis. On this occasion, the Sentinels aligned themselves with the American Medical Association and continued their standing partnership with Woman Patriot Publishing Company.Footnote 100 By the late 1920s, the Sentinels had helped defeat numerous proposals to expand the purview of the federal government; gendered ideas about the sovereignty of the family had enabled the organization to forge important alliances in each instance.

The Sentinels in the New Deal

As the nation fell into an economic depression after the stock market crash of 1929, the Sentinels broadened their focus beyond the Children's Bureau, opposing any congressional proposal that included federal aid to the states or economic relief to the public at large. They opposed the dole throughout the winter of 1930–1931—a time when the unemployment rated doubled to nearly 16 percent.Footnote 101 The organization displayed a tenacious and unwavering commitment to its antistatist principles during the depths of the downturn. In February 1931, Frank L. Peckham appeared before Congress on behalf of the Sentinels to oppose a proposal for federal cooperation with the states for the rehabilitation and vocational training of disabled people. “I am not here in favor of crippled children,” Peckham clarified, stating, “I am here opposed, however, to further crippling American principles of government.”Footnote 102 The states, the Sentinels explained, were now “beggars” who needed to be “saved from themselves.”Footnote 103

Franklin Roosevelt's presidency and the full roster of New Deal economic relief programs left the Sentinels in despair. The principles of government they had fought to maintain for over a decade, Lincoln bemoaned in a July 1933 letter, had been “thrown into the discard.” In a public statement to Roosevelt, the Sentinels urged that he show restraint in his response to the economic crisis, which they argued had been largely brought about by “over centralized control of business and industry.” It behooved the president to respect private property rights, stop Congress from passing any new taxes, and stay out of labor relations, as the right to work was sacrosanct, and no government was entitled to impair it. The Sentinels reminded the president that he had taken an oath to uphold the Constitution, “not to overthrow it.”Footnote 104

In the early years of the Depression, the Sentinels made a determined effort to sell their antistatist agenda but struggled to survive as an organization. In 1932, they sponsored twenty national radio addresses and made concerted attempts to attract more prominent speakers to raise their profile. Despite this outreach, neither the executive committee nor membership base drew in many new recruits. A notable exception was the addition of the first prominent Catholic to the executive committee, Father Edmund Walsh of Georgetown University, who would come to be known as one of the most vociferous anticommunist warriors of the mid-century. Walsh's rousing radio address brought in more letters of inquiry than did any other address. But while the Sentinels claimed to have 10,000 subscribers in 1931, only 1,000 members paid nominal dues, and the executive committee admitted that it lacked the resources to follow up on the interest the radio talks had generated.Footnote 105 A lack of funds saw the Sentinels’ long-standing partner, the Woman Patriot Publishing Company, cease publication in 1932. But Balch, who had long served both organizations, and Mary Kilbreth would continue their antistatist activism through the Sentinels. The Sentinels found renewed energy in 1933 when proratification forces capitalized on the changing political mood to make a new effort to ratify the federal Child Labor Amendment.

Indeed, as the New Deal revitalized new threads of antistatist activism, the Sentinels jostled to define their place in this new political landscape. Many business leaders initially supported the election of Roosevelt, and the president's support for the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment handed a welcome victory to the Sentinels’ 1920s anti-Prohibition compatriots. The businessmen and prominent Democrats behind the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, however, quickly soured on Roosevelt after he introduced the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933, and they resolved to found the American Liberty League.Footnote 106 The League's goals clearly echoed those of the Sentinels’, and in June 1934, William H. Stayton, the secretary of the Liberty League, wrote to Lincoln to propose a merger.

The idea of a merger appealed to Lincoln, who strongly supported the League's goals and worried about the Sentinels' ability to attract funds and publicity in the League's shadow. The national director of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, Raymond Pitcairn, the son and heir of John Pitcairn, a Gilded Age industrialist, had already assumed the national chairmanship of the Sentinels and begun to pour in money. Both Lincoln and Stayton worried that the duplication of efforts would diminish the effective pursuit of the two groups’ common cause. For Lincoln, however, the Liberty League's undetermined position on the Child Labor Amendment proved a sticking point—a cause the Sentinels were unwilling to abandon. While Stayton strongly identified with the Sentinels’ opposition to the Child Labor Amendment, Jouett Shouse, a leading anti-Prohibition Democrat and founding member the Liberty League, had voted for the Child Labor Amendment in 1924 and had yet to reverse his support. The Liberty League's primary backers, the du Pont brothers, ultimately came out against the amendment. But in October 1934 with the League's position unresolved, Stayton advised that the Sentinels should remain its own entity to continue its campaign against the revived effort to ratify the Child Labor Amendment, noting the momentum the organization had already built.Footnote 107 In the end, the Sentinels formed the nucleus of anti–New Deal groups that supported the more prominent Liberty League's goals. The group shared the same principles, the same small overlapping membership base, and an even smaller base of financial backers, with the same businessmen and corporations providing 90 percent of all anti-administration funds.Footnote 108

The National Industrial Recovery Act had rekindled the fight over the federal Child Labor Amendment by including provisions that outlawed industrial child labor. Seeking to cement the gains made under the act and to extend protections to children in agriculture, Grace Abbott, Lillian Wald, and Florence Kelley, three driving forces behind the Children's Bureau, led a renewed push to ratify the amendment in 1933. With little ado, fourteen states ratified the amendment that same year. Twelve of those fourteen states reversed a previous vote by the state legislature to reject it.Footnote 109 By 1935, the battle erupted more fiercely when the Supreme Court struck down the National Industrial Recovery Act and Roosevelt joined the fight for ratification, leaning on all Democratic governors to pursue it. Cracks in the once bipartisan support for the federal Child Labor Amendment, first introduced in a Republican Congress in 1924, were now fully opened, as the Republican opposition became uniform.Footnote 110

Before President Roosevelt had even entered the ratification fight, however, the Sentinels had already done significant damage, lobbying thirteen states to reject ratification in 1934.Footnote 111 In late 1933, the Sentinels used their executive committee to establish the National Committee to Protect the Child, Home, School and Church, which operated out of St. Louis, Missouri. The National Committee's executive included Balch, Kilbreth, and Lincoln. Sterling Edmunds, a new member of the Sentinels, headed the committee. A prominent Missouri lawyer and member of the American Bar Association, Edmunds was an anti–New Deal Democrat who led a Democratic campaign against Roosevelt as a member of the Southern Committee to Uphold the Constitution.Footnote 112

The final member of the executive committee was William Dameron Guthrie, a laissez-faire constitutional lawyer, lifelong Republican, and devout Catholic who had long shared the Sentinels’ worldview about the threats that progressivism posed to private property rights and the patriarchal family. Guthrie had first risen to national prominence in 1895, when he appeared before the Supreme Court in Pollock v. Farmers Loan Trust Co. in a successful challenge to the constitutionality of the national income tax. (The decision in Pollock had been superseded by the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913. In the 1930s, the Sentinels added the repeal of the Sixteenth Amendment to their platform.) Over the next thirty years, Guthrie dedicated his legal work to challenging Progressive Era reforms, culminating in his successful challenge to an Oregon school law on behalf of the National Catholic Welfare Council in the Supreme Court case Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925). The Oregon law, struck down before it came into effect, would have made attendance at public schools in Oregon compulsory, effectively outlawing parochial education. Echoing the political rhetoric of the Sentinels, Guthrie had argued that family government, like state government, had its own separate sphere of jurisdiction beyond the reach of the state. Striking down the law as unconstitutional, the court declared that the “child was not a mere creature of the state,” and held that parental rights were a fundamental liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.Footnote 113 Guthrie's role in the National Committee again aligned the Sentinels with the Catholic Church in the antiratification fight.

In the 1930s, the Sentinels argued once again that the amendment posed dire threats to individual liberty and to the American home. In February 1934, the National Committee kicked off its campaign with four national radio addresses delivered by Butler; Clarence E. Martin, the former president of the American Bar Association; Lawrence Lowell, the former president of Harvard University; and James Reed, a former U.S. Democratic senator from Missouri. Reed stated that he could imagine “nothing more inimical to our country or destructive of our civilization” than the proposed Child Labor Amendment: “Our American civilization and the civilization of the Anglo-Saxon race has been based upon the home, upon the authority of the parent, upon the discipline of the family, upon the industry and common effort of the family.”Footnote 114 The amendment, he warned, would replace the authority of the parent with the authority of Congress.

The Sentinels leveraged their extensive connections within the legal community to lean on the American Bar Association to come out against the amendment. Since its inception, the ranks of the Sentinels’ executive committee had been filled with lawyers, including Lincoln, its congressional spokesmen Peckham, and Cadwalader, who had long dueled with leading progressive lawyers, such as Roscoe Pound and Ernst Freund, over the constitutional wisdom of the amendment. In the 1930s, Guthrie and Edmunds convinced the American Bar Association to throw its professional heft behind the antiratification campaign, persuading the association to form a Special Committee Against the Ratification of the Child Labor Amendment in early 1934. Guthrie was appointed chairman and authored an influential report, relying on his victory in Pierce as a constitutional bedrock to argue that the amendment invaded the rights of parents. “The Amendment should be actively opposed as unwarranted invasion by the Federal Government in the field in which the rights of the individual states and of the family are and should remain paramount,” the report concluded, warning that the amendment would grant Congress power that “could be exercised so as to invade the privacy of the home and the sacred authority, control and duty of parents.”Footnote 115 Guthrie also convinced the American Bar Association to use its state associations to lobby against ratification in 1935.Footnote 116

The Sentinels also solidified their partnerships with prominent Catholics and with evangelical and mainline Protestant religious leaders, and used the institutional resources of their churches to disseminate antiratification materials. Edmunds was a member of the Westminster Presbyterian Church of St. Louis, and he secured the support of his pastor, Dr. William Crowe. Crowe sent a letter on behalf of the National Committee to every minister of the Southern Presbyterian Church to call their attention to the “evils in the so-called ‘child labor’ Amendment.” (Machen also unsuccessfully lobbied the Northern Presbyterian Church to oppose the amendment.)Footnote 117 Across the Midwest, the Sentinels coordinated with conservative religious leaders, issuing a joint statement of the opposition of twelve ministers from Methodist, Southern Baptist, Presbyterian, and Lutheran Churches, as well as the Archbishop of St. Louis. By the 1930s, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church was united in its opposition to the amendment, and the Missouri Lutheran-Synod joined the fight in the Midwest as well.Footnote 118

In Boston and New York, where the Sentinels’ leadership remained rooted, the Sentinels again used alliances with Catholic leaders to unite wet Republicans and Catholic Democrats. New York, as the home state of the president, was considered a key battleground for ratification in 1935. Guthrie and Butler established the New York Committee Against Ratification in 1934, and Guthrie worked his connections with the Catholic Church, whose public condemnation of the amendment was enough to lead many New York Democrats with large Catholic constituencies to disregard the directions of Roosevelt and the Democratic governor.Footnote 119 In Massachusetts, Lincoln appeared before the General Court to read the letters of “unequivocal opposition” penned by Cardinal O'Connell and the Episcopal Bishop Lawrence.Footnote 120 By March 1935, a further sixteen states had voted to reject the amendment, and the Sentinels declared it “dead.”Footnote 121

While the Sentinels waged war against the Child Labor Amendment under the auspices of the National Committee, the organization concurrently spoke out against the New Deal in Congress. Between 1933 and 1935, the Sentinels appeared in Congress to register their opposition to the Social Security Act, the establishment of a national department of education, the National Labor Relations Act, and the Public Utility Holding Company Act, all while calling for the repeal of the Sixteenth Amendment and the elimination of the “general welfare clause” of the U.S. Constitution.Footnote 122 In 1935, Pitcairn used the Sentinels as a vehicle for his own personal crusade against a provision of the Revenue Act of 1934, which required the small percentage of Americans who paid income tax to disclose their income on a “pink slip” that would become publicly available. Declaring that the “pink slip” was an affront to individual liberty and to the Constitution, Pitcairn coordinated a targeted campaign to inundate members of Congress until the provision was repealed.Footnote 123

In May 1935, the Sentinels regrouped at Faneuil Hall in Boston to celebrate their recent victories against “federal paternalism.” Though Pitcairn had pulled the Sentinels in a new direction with his anti-tax appeal, the organization retained a common purpose and ideology, revealed in the persistent gendering of the individual citizen as a male property owner. Pitcairn emphasized that the fundamental constitutional rights that the Sentinels fought to preserve were “profoundly important” to all “productive self-reliant citizens,” and warned that the current administration imperiled the rights of the “home owner,” the “wage earner,” the “businessman,” and the “professional man.” The Sentinels used the same valorizing language to describe the “sanctity of his home” and the “sanctity of his contracts” in describing the property rights protected by the Constitution. At Faneuil Hall, Pitcairn and the original founders of the Sentinels decided to celebrate their recent victories in the antiratification and pink slip campaigns with a weeklong celebration of the Constitution in Philadelphia that October. The exhibit, which attracted 30,000 visitors, used poster displays to portray the dangers of the New Deal and debuted a new and controversial cartoon film mocking the administration.

The celebrations were short lived. In 1936, the Black Committee called the Sentinels to testify before Congress on the sources of their lobbying funds. Chaired by Hugo Black, the committee oversaw a Senate inquiry into the lobbying efforts against the Public Utility Holding Act. Its broader aim, however, was to expose the money and the sinister intents of anti-administration groups, especially the American Liberty League, who were “tried in absentia” and “declared guilty by association” due to their thick links with groups like the Sentinels.Footnote 124 The hearings were the first time the Sentinels were forced to disclose their financial operations, revealing that the organization had been limping along on a budget of approximately $6,000 per annum in the early 1930s until Raymond Pitcairn had joined the Sentinels and injected approximately $100,000 “on loan” to the organization. During that eighteen-month period, the Sentinels had also received support from other prominent businessmen, including Howard Pew and Alfred Sloan of General Motors. Though it paled in comparison to the more than $350,000 the du Pont brothers poured into anti–New Deal lobby groups, the Pitcairn family contribution ranked third highest in the donations disclosed in the Black Hearing.Footnote 125 The findings that the same businessmen bankrolled all anti-administration groups tainted the groups’ efforts to position themselves as disinterested patriotic organizations.

Beyond the damage done by the financial revelations, the reputation of the Sentinels and their allies was irreparably tarnished by the recovery of private communications that revealed the Sentinels President Lincoln's anti-Semitic views. In correspondence subpoenaed by the Black Committee, the Sentinels were asked about an inquiry Lincoln had received from a New York lawyer concerning what the Sentinels planned to do about the “Jewish threat.” Lincoln responded that the “Jewish threat is a real one” and that the real opportunity to defeat it lay in defeating Roosevelt in the forthcoming election.Footnote 126 The revelation spread through the press like wildfire. Sloan issued a public statement denouncing the Sentinels, adding that he would not be making any further donations to a group that spread religious bigotry.Footnote 127 Lincoln stepped down as president of the Sentinels and resigned his post from the Massachusetts State Board of Tax Appeals under pressure, though he maintained his comments had been “misconstrued.”Footnote 128 The only political group that would associate with Lincoln after the scandal were the die-hard anti-feminists, led by Kilbreth and her ailing Woman Patriot Committee, who asked Lincoln to act as their treasurer in 1940.Footnote 129 Despite the Sentinels’ efforts to drop Lincoln, they were unable to escape anti-Semitic charges, and they faded from public view before officially disbanding in 1944.Footnote 130 In the 1940s, the American Liberty League, who had attempted to distance itself from the Sentinels, also disbanded, having failed more broadly to sell a free-enterprise agenda in the New Deal era.Footnote 131

Conclusion

At the end of the Sentinels’ existence, the defeat of the Child Labor Amendment stood out as the singular achievement of their antistatist campaigns. By 1937, only twenty-eight states had ratified the amendment, ten short of the necessary majority. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which included regulations to end industrial child labor, replicating the mechanism and limited scope of the first national child labor law of 1916. The Sentinels’ critics were not wrong to charge that the organization had scotched the amendment with a well-financed scare campaign backed by industry. But the Sentinels were also more than a big business propaganda machine parading in patriotic garb.Footnote 132 The content of the Sentinels’ antiratification campaign reflected the antifeminist, anticommunist, and antiregulatory interests that made up the Sentinels’ leadership ranks, but also allowed the group to build antistatist coalitions far beyond its small membership base. The Sentinels’ belief in the sovereignty of family government animated their opposition to the Nineteenth Amendment, triggered their formation, and sustained the organization over time. It also provided the language to sell an antistatist agenda that appealed across sex, faith, class, and partisan lines.

While the Sentinels had petered out as a political force by the 1940s, their politics reveal the deep roots of the New Right. Many of the Sentinels' key players passed away in the 1930s and 1940s. A few notable Sentinels, however, such as Cadwalader, carried their conservative activism well into the twentieth century. Cadwalader, who had co-filed a Supreme Court challenge to the Nineteenth Amendment in Leser v. Garnett (1922) and served as the chairman of the Sentinels’ executive committee, later coordinated Strom Thurmond's 1948 Dixiecrat campaign in Maryland and filed a brief on behalf of his Mount Royal Protective Association in defense of racially restrictive property covenants in the Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer (1948).Footnote 133 Cadwalader's career points to the connections and continuities between conservative opposition to the enfranchisement of women and opposition to racial integration—politics that took the form of a conservative constitutional language of individual liberty, states’ rights, and local self-government. Other Sentinels served as a source of inspiration for late-twentieth-century conservatives. Gresham became a muse to mid- to late twentieth-century evangelical conservatives from Francis Schaeffer to Jerry Falwell.Footnote 134 In Gresham's work, they found a blueprint for an evangelical conservatism that fused religious fundamentalism, libertarianism, and antifeminist politics.

The Sentinels’ activism highlights important affinities among conservative constituencies that found common cause around the politics of the family in the 1920s and 1930s. The contributions of conservative lawyers, and the ideology of constitutional nationalism that the Sentinels promulgated, suggest a longer history to the conservative constitutional movement that postwar scholars have begun to sketch out.Footnote 135 The National Association of Manufacturers' efforts to sell free-enterprise politics in the 1940s formalized alliances with religious conservatives that the Sentinels had forged in their antiregulatory campaign in the decades prior.Footnote 136 Indeed, the partnerships forged between the high-church Protestants who made up the ranks of the Sentinels and conservative Catholics over the politics of the family in the 1920s and 1930s suggest that the cross-faith alliance forged over abortion, antifeminism, and sexuality in the late twentieth century represented the resurgence of an old pairing. Overall, the story of the Sentinels should remind us that an antiregulatory business agenda originally formed in opposition to maternalist politics, and that histories of free-market conservatism cannot be divorced from the politics of gender, sexuality, and the family.Footnote 137