No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

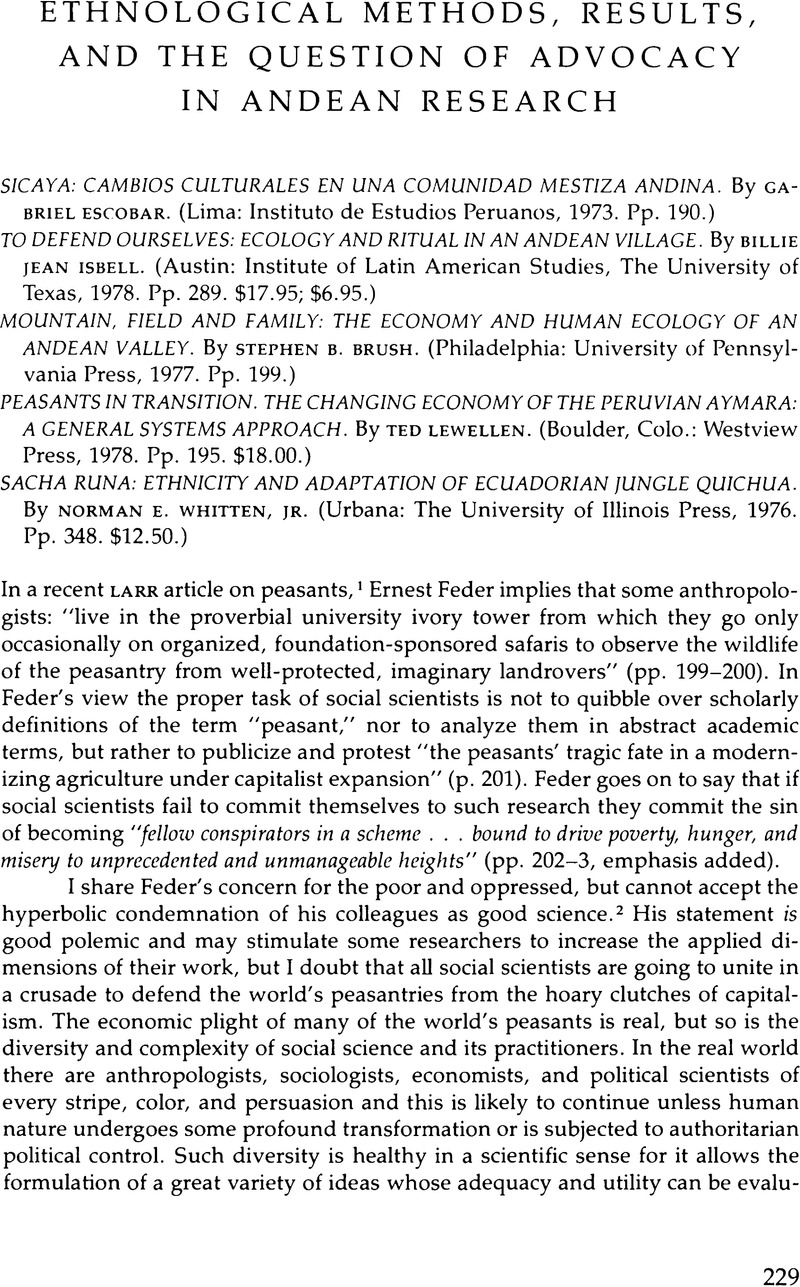

Ethnological Methods, Results, and the Question of Advocacy in Andean Research

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Books in Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1980 by Latin American Research Review

References

Notes

1. Ernest Feder, “The Peasant,” LARR 13, no. 3 (1978): 193–204.

2. Some may take my critique of Feder's position as an indication that I am unconcerned about the well being of peasant and tribal peoples in the face of modernization. For this reason alone I refer readers to the following items: “Development Without Them in Brazil's Northeast and Amazon,” Caribbean Review 8, no. 2 (1979): 50–53; “Letter to the Editor, Indians on the Amazon,” Time (Foreign Editions), 13 February 1978, p. 1; “Environment, Production and Subsistence: Economic Patterns in a Rural Otomi Community,” in Michael Kenny and H. Russell Bernard, eds., Ethnological Training in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America, 1973) pp. 143–62; “Indians, Oil, and Colonists: Contrasting Systems of Man-Land Relations in the Aguarico River Valley of Eastern Ecuador,” Latinamericanist 8, no. 2 (1972): 1–3; “Ideation as Adaptation: Traditional Belief and Modern Intervention in Siona-Secoya Religion,” in Norman E. Whitten, Jr., ed., Cultural Transformations and Ethnicity in Modern Ecuador: Ethnological Perspectives (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, in press); “The Jesuits and the SIL: External Policies for Ecuador's Tucanoans through Three Centuries,” in S⊘ren Hvalkof and Peter Aaby, eds., Is God an American: An Anthropological Perspective on the Missionary Work of the Summer Institute of Linguistics in Latin America (Bornheim-Merton, W. Germany: Lamuv Verlag GmbH, in press).

3. William Mangin, “Urbanization Case History in Peru,” pp. 47–54 and Paul L. Doughty, “Behind the Back of the City,” pp. 30–46 in William Mangin, ed., Peasants in Cities (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1970).

4. See Victor Barnouw, Culture and Personality (Homewood, Ill.: The Dorsey Press, 1973), pp. 129–47 for a discussion of various critiques of Mead's early work.

5. Marvin Harris, The Rise of Anthropological Theory (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1968), pp. 605–33.

6. See, for example, Earl R. Babbie, The Practice of Social Research, 2d ed. (Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1979), pp. 13–25 for a discussion of the traditional model of science and the realities of scientific practice.

7. Good introductions to the state of the art in ecological anthropology may be found in Andrew P. Vayda and Roy A. Rappaport, “Ecology: Cultural and Non-Cultural,” in James A. Clifton, ed., Introduction to Cultural Anthropology: Essays in the Scope and Methods of the Science of Man (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1968), pp. 477–97; Donald L. Hardesty, Ecological Anthropology (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1977); and Emilio F. Moran, Human Adaptability: An Introduction to Ecological Anthropology (North Scituate, Mass.: Duxbury Press, 1979).

8. Examples of the use of input-output analysis in the study of nonindustrialized subsistence systems may be found in Roy A. Rappaport, Pigs for the Ancestors: Ritual in the Ecology of a New Guinea People (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1968) and Bernard Nietschmann, Between Land and Water: The Subsistence Ecology of the Miskito Indians, Eastern Nicaragua (New York: Seminar Press, 1973).

9. For an introduction to the debate between the “formalist” and “substantivist” schools of thought in economic anthropology see the collection of papers in Edward E. LeClair, Jr. and Harold K. Schneider, Economic Anthropology: Readings in Theory and Analysis (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968).

10. The correct spelling in Ecuador is “Quichua,” and not “Quechua” as in Peru and Bolivia. This is a sore point for researchers who have worked in Ecuador and who are repeatedly “corrected” by colleagues whose experience is in other Andean countries.

11. Udo Oberem's, Los Quijos: historia de la transculturación de un grupo indígena en el Oriente Ecuatoriano (1538–1956), 2 vols. (Madrid: Faculdad de Filosophia y Letras de la Universidad de Madrid, Memórias del Departamento de Antropología y Etnología de América, 1971) is the major modern source on the Quijos Quichua in Spanish.

12. See Michael Harner, The Jivaro: People of the Sacred Waterfalls (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday/Natural History Press, 1972) and Henning Siverts, Tribal Survival in the Alto Marañon: The Aguaruna Case (Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs Document No. 10, 1972).

13. The situation of the Campa is described in John H. Bodley, Tribal Survival in the Amazon: The Campa Case (Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs Document No. 5), and Gerald Weiss, The Cosmology of the Campa Indians of Eastern Peru (Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms, 1969).

14. An overview of the Cornell Peru Project is presented in Henry F. Dobyns, Paul L. Doughty, and Harold D. Lasswell, Peasants, Power, and Applied Social Change: Vicos as a Model (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1971).