No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

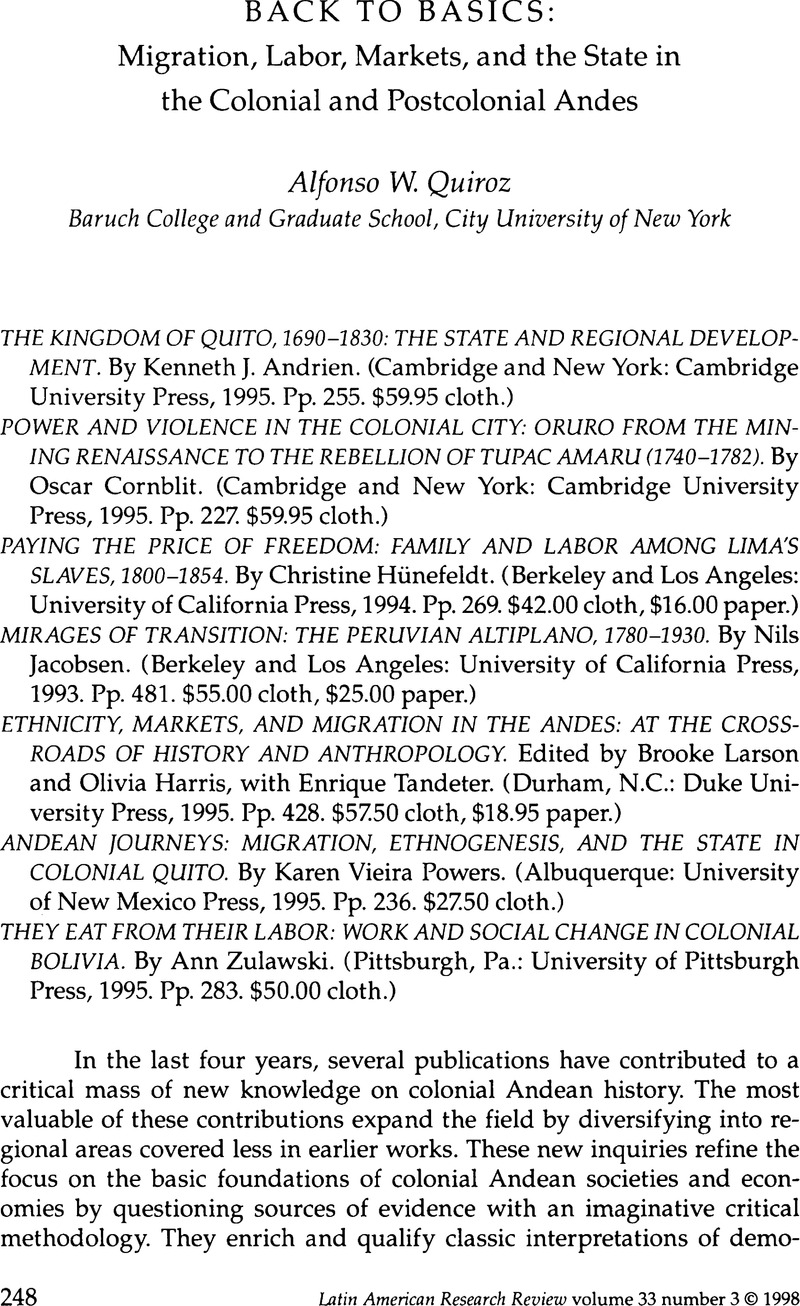

Back to Basics: Migration, Labor, Markets, and the State in the Colonial and Postcolonial Andes

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1998 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Most notable are the contributions of Noble David Cook, Herbert Klein, Franklin Pease, Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz, Karen Spalding, Steve Stern, Enrique Tandeter, Ann Wightman, and Nathan Wachtel.

2. See especially the works of Rolena Adorno, Sabine MacCormack, and Irene Silverblatt.

3. Works by Kendall Brown, Keith Davies, and Susan Ramírez on colonial Peru have contributed to the rigor of this regional perspective. See Brown, Bourbons and Brandy: Imperial Reform in Eighteenth-Century Arequipa (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1986); Davies, Landowners in Colonial Peru (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984); and Ramírez, Provincial Patriarchs: Land Tenure and the Economics of Power in Colonial Peru (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1986).

4. Nicolás Sánchez-Albornoz, Indios y tributos en el Alto Perú (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978); and Ann W. Wightman, Indigenous Migration and Social Change: The Forasteros of Cuzco, 1570–1720 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1990).

5. Suzanne Alchon, Native Society and Disease in Colonial Ecuador (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

6. See Jeffrey A. Cole, The Potosí Mita, 1573–1700: Compulsory Indian Labor in the Andes (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1985); and Enrique Tandeter, Coercion and Market: Silver Mining in Colonial Potosí, 1692–1826 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993).

7. Irene Silverblatt, Moon, Sun, and Witches: Gender Ideologies and Class in Inca and Colonial Peru (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987).

8. María Rostworowski, Etnía y sociedad: Costa peruana prehispánica (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1977); a second edition entitled Costa peruana prehispánica was published in 1989.

9. Kenneth Andrien, Crisis and Decline: The Viceroyalty of Peru in the Seventeenth Century (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985); and “Economic Crisis, Taxes, and the Quito Insurrection of 1765,” Past and Present, no. 129 (1990):104–31. See also Martin Minchom, The People of Quito, 1690–1810: Change and Unrest in the Underclass (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1994); and Carlos Contreras, El sector exportador de una economía colonial: La costa del Ecuador entre 1760 y 1820 (Quito: Abya-Yala, 1990).

10. Autarky might be a better concept to employ in describing the condition of Quito in the seventeenth century.

11. This perspective has been taken to new levels in Mark Thurner, From Two Nations to One Divided: Contradictions of Postcolonial Nationmaking in Andean Peru (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997).

12. See also Carlos Aguirre, Agentes de su propia libertad: Los esclavos de Lima y la desintegración de la esclavitud, 1821–1834 (Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Católica, 1993).