INTRODUCTION

A common understanding of violent sexist humor is that it is a male homosocial practice that reproduces patriarchal order while normalizing sexual violence (Pérez & Green Reference Pérez and Greene2016; Nichols Reference Nichols2018). Ridicule, banter, and aggressive joking are often associated with certain types of masculinities, or with ‘lad culture’ (Kotthoff Reference Kotthoff2006; Nichols Reference Nichols2018), and homosociality (Hickie-Moodey & Laurie Reference Hickie-Moodey, Laurie and Papenburg2017). It has been shown that teasing and humor may serve as a way to preserve the gender order, as well as of constructing subjects that self-regulate, in line with such hegemonic orders (Abedinifard Reference Abedinifard2016). Kramer (Reference Kramer2011:136) investigated debates regarding internet rape-jokes by exploring ‘humor ideologies’, arguing that ‘telling, laughing at, or disapproving of a rape joke [is] a socially significant act through which one can index one's identity as a “type” of interlocutor, person, and citizen’. However, in this article we examine how such events come about collaboratively, and what happens during both the delivery and uptake of such humor, by scrutinizing the social interaction in an actual recorded case. We do this by analyzing an episode of a Swedish podcast, run by a group of male comedians, that evoked strong public criticism and condemnation due to its rape humor and threats of violence.

Aired in 2015, the podcast and the uproar that followed can, in a Swedish context, be understood as a precursor to the #metoo movement, which so clearly illuminated the extensiveness of sexism and violence towards women. While there were many virtues of this movement, there was also a growing critique of the focus on individual, famous men. It was argued that disclosures of celebrities as specific (unique) offenders entailed the risk that sexism might be understood as something personal and individual, rather than social and structural. The aftermath of the podcast has many similarities with this discussion. The interaction in the podcast very clearly breached taboos in Swedish public discourse—including the violation of a gender equal ideology. This ideology, of course, does not mean that Sweden is a gender-equal society, yet, making explicit anti-feminist claims is highly controversial in Swedish public discourse. The media debate that followed was marked by a disdain for the comedians in the podcast, and discussions focused on the comedians’ personal misogynistic values, their laddish attitudes, and possible alcohol abuse. The comedians involved were not particularly known for sexist or misogynistic humor, adding to the shock-value of the podcast.

In this article, we emphasize the social aspect of sexist humor, specifically, how sexist humor is a joint project that develops gradually in interaction. We argue that the heavily sexist talk employed in the podcast episode cannot be understood solely in terms of the performance of a hegemonic heterosexual masculinity (Connell Reference Connell1995; Connell & Messerschmidt Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005). Nor do we engage in an analysis of inner misogynist ideas among the podcasters. Our concern is rather with how subject positions (Wetherell Reference Wetherell1998; Althusser Reference Althusser2001), as well as morality and taboos, are being constructed and transgressed in social interaction. We want to illuminate the laughter surrounding rape humor as a collective and interactive phenomenon that can be understood in terms of desire and repression (Butler Reference Butler1987, Reference Butler1990; Billig Reference Billig1999)—and as such, something that generates enjoyment and pleasure, as well as arousing anger and fear among the men in the podcast studio. In doing this, we wish to make a contribution to the understanding of desire in social interaction, as a part of discourse, or what Wetherell (Reference Wetherell2013) calls an affective practice.

AFFECT AND DISCOURSE

Our interest in taboo-breaking talk, and interactional pleasure, leads us to incorporate affect into our analysis. As Wetherell (Reference Wetherell2013) explains, the affective turn in social sciences grew out of a wish to theoretically interweave the material and the biological with the social and cultural. From a Massumian (Reference Massumi2002) point of view, the distinction between discourse and prediscourse is fundamental to uphold, and from that epistemological claim, there follows a distinction between affect and emotion. Emotions can be defined as the way people make sense of bodily, material, and nondiscursive affects through language. As Reeser & Gottzén (Reference Reeser and Gottzén2018:5) put it, ‘[a]rticulating an emotion, means it is already too late to find affect’. Moreover, Sedgwick (Reference Sedgwick2003), in her critique of ’paranoid readings’ within discursive and critical theory, argues that the anti-essentialism in social constructionist works has led to an analysis that tries to critically reveal and unmask the studied phenomena in a way that has failed to account for embodied experiences and feelings.

Although affect and emotion were neglected for a long time throughout critical social theory (see also Billig Reference Billig2002), it now seems as if discourse is met with a similar kind of suspicion. For many leading affect theorists, the affective turn in social sciences has meant a shift away from discourse towards the prediscursive, towards looking at affect as something nonrepresentational, and beyond linguistic practices (see Massumi Reference Massumi2002; Thrift Reference Thrift2008). However, as Wetherell points out, this conception of discourse as being synonymous with ‘the conscious, the planned, and the deliberate while affect is understood as automatic, the involuntary, and the non-representational’ (Reference Wetherell2013:52, italics in original) creates an unfruitful dichotomy. Affect is rather, Wetherell states, both an embodied and social meaning-making practice. Milani, Levon, & Glocer (Reference Milani, Levon and Glocer2019) show, for example, how a truly sociocultural and ideological phenomenon such as nationalism can be understood as enactments of affects—of mourning, shame, guilt, and fear of loss. In a similar vein, Ahmed presents a theory which states that emotions are not located in peoples’ inner selves, but circulate and stick to certain bodies. Emotions do things, Ahmed writes. We therefore ‘need to consider how [emotions] work, in concrete and particular ways, to mediate the relationship between the psychic and the social, and between the individual and the collective’ (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2004:119).

While acknowledging Ahmed's theory, Wetherell (Reference Wetherell2013) urges us to not forget about participants’ interactional work in such processes. She therefore suggests an analysis of people's everyday affective practices. ‘Affective practice focuses on the emotional as it appears in social life and tries to follow what participants do’ (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2013:4). Wetherell's perspective, Malmqvist (Reference Malmqvist2015:736) notes, investigates the articulation of emotions while seeing them as inextricably intertwined with the ordered patterns of social relationships, as they emerge in affective discursive practices. Wetherell thus treats affect and emotion as inseparable from social interactions and discursive practices, situated in the settings in which these take place. It is precisely through these practices that affects are made meaningful (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2013).

Thus, we use the concept of affective practice, seen as a patterned activity and a way of doing things in interaction (see Wetherell Reference Wetherell2012:23). There is a small but growing number of empirical studies within this field (for instance, Malmqvist Reference Malmqvist2015; Wetherell, McCreanor, McConville, Moewaka Barnes, & le Grice Reference Wetherell, McCreano, McConville, Barnes and le Grice2015; Wetherell, McConville, & McCreanor Reference Wetherell, McConville and McCreanor2019); and we would like to contribute to this set of studies with our exploration of desire and repression as affective practices.

TABOO, DESIRE, AND HUMOR IN TALK

In her seminal book Gender trouble, Judith Butler (Reference Butler1990) urges us to see gender identities as enactments based on reiteration within dominant norms or discourses. In an often neglected chapter in the book, Butler emphasizes, with references to psychoanalytical theory, that this performative work of identification is enacted in relation to what is forbidden and repressed. She writes:

[Because] identifications are the consequence of loss, gender identification is a kind of melancholia in which the sex of the prohibited object is internalized as a prohibition. This prohibition sanctions and regulates discrete gendered identity and the law of heterosexual desire. (Butler Reference Butler1990:80)

Later on, Cameron & Kulick (Reference Cameron and Kulick2003) further developed Butler's point by stating that what is performed in talk is always linked to all that cannot be expressed, told, or achieved in communication. They write that focusing only on the explicitly expressed performance of identity in talk risks ‘a kind of conscious claim-staking by a subject who knows exactly who s/he is, or wants to be’ (Cameron & Kulick Reference Cameron and Kulick2003:128). In other words, various subject positions emerge in interaction, on the basis of not only what is possible to express, but also what remains untold and repressed in talk. Similarly, we do not take for granted that sexist talk reflects men's intentional doing of certain masculinities. As Kiesling (Reference Kiesling2018:4), drawing on Ochs (Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992), puts it: ‘When I “speak like a man”, I'm not usually thinking about doing so because I want to be a man but because I want to do something else that happens to be culturally linked to masculinity’. By also taking the forbidden into account, it follows that conscious performance is not the same as performativity (see Kulick Reference Kulick2003:140). Thus, we consider identities, as well as affects, as emergent in interaction, and never fully owned by the participants. Our presumption is, as Butler writes (Reference Butler1997:15), ‘that speech is always in some ways out of control’.

We shall follow Cameron & Kulick's (Reference Cameron and Kulick2003) call to investigate taboo and desire in talk. However, when analyzing the forbidden or taboo in this article, we do not approach it in terms of a forbidden desire repressed by an inner psyche, or analyze it as being only that which is impossible to enact. Rather, we use taboo in a wider sense, with a broad meaning that includes explicit language. Such talk may be reproduced over and over again (and is hence not silent), but can cause public disdain, aversion, and scandal. Further, we contend that desire is not reducible to the domain of the erotic. Instead, desire involves, in a wider sense, how people create amusement, pleasure, or enjoyment, in and through language use. One possible way of constructing homosocial intimacy, Kiesling (Reference Kiesling2005) shows in his research on American homosocial fraternities, is by ‘transgressing public taboos: talking explicitly about sex, engaging in unsafe, dangerous, and prohibited behavior, and using taboo lexis in public situations’ (Reference Kiesling2005:699). Thus, certain loaded words and taboo-breaking ways of talking can be thought of as constructing desire (see also Milani & Jonsson Reference Milani and Jonsson2011; Jonsson Reference Jonsson2018). To put it differently, what is socially prohibited and therefore desired is constituted in language—not outside of it.

Similarly, Billig (Reference Billig1999) suggests that repression is a discursive practice. It is part of one's banal and daily activities, such as when changing the subject or avoiding topics in social interaction. Billig urges us to not think of the unconscious—or affect we may add—as a dark core of mysterious innerness that controls our actions, but rather as something that is being constructed in and through language. These discursive moves can actually be seen as examples of affective practices. The skills of avoiding topics, ignoring talk, or masking and under-communicating certain reactions to situations and feelings (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2013:135) are important resources available to meaning-making processes in affective practices.

To this, we would add our contention that the forbidden also lies in jokes and humor, such as, for example, when taboos are explicitly being exploited for thrilling enjoyment. According to Freud's (Reference Freud1905/1991) theory of laughter, humor allows expressions of what is otherwise repressed. The taboo connected to aggression, as well as to sexual pleasure, can therefore explain the many jokes on the same themes—in laughing at such jokes, repressed desire may be relieved, yet hidden as jokes (see also Billig Reference Billig2005:159).

Following Billig's discursive take on Freud, we treat the podcast as full of humorous discursive practices because of its original framing, while not evaluating the quality of such humor. Additionally, humor does not necessarily entail that it is morally superior, or the bearer of any ‘good’ values (Billig Reference Billig2001). It has been pointed out that humor can create rapport, or a sense of belonging, while also constructing a space where the speaker becomes free of responsibility for what is said (Boxer & Cortés-Conde Reference Boxer and Cortés-Conde1997; Norrick Reference Norrick2003; Franzén & Aronsson Reference Franzén and Aronsson2013). The listener is also expected to get the joke and not take what is said seriously (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1990)—to be able to understand a humorous framing of an utterance is a conversational skill required in many social contexts. Billig (Reference Billig2005) points to how humor is deeply connected to social order, and how humor can be used as both a means to upset it, and to reproduce it (see also Jonsson, Franzén, & Milani Reference Jonsson, Franzén and Milani2020). Ridicule or friendly banter plays an important role in the production of desirable subjectivities by making both social order and breaches of it visible through laughter, even at seemingly banal humor (Billig Reference Billig2005). In the sense that humor, including sexist humor, is connected to identification (for humor and the construction of gender identities see Kotthoff Reference Kotthoff2006; Abedinifard Reference Abedinifard2016), so also are responses to humor. Both laughter and unlaughter (a lack of laughter where it might be expected; Billig Reference Billig2005) construct identity, and have to be understood in relation to humor ideologies (at times, as with rape humor, highly morally imbued; Kramer Reference Kramer2011)—through the production and uptake of transgressive humor, people may position themselves vis-á-vis a social order. In humor practices, Billig reminds us, the participants may also orient to multiple and contradictory goals.

Finally, Benwell (Reference Benwell2011) has critically pointed out the indemonstrable nature of the psychoanalytical approach from which Butler or Cameron & Kulick picked the concepts of desire and identification (see also the critique from Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2004). The focus on psychoanalytical concepts, such as repression and desire, might have distanced some of their sociolinguistic and discursively oriented readers. This article may serve to reintroduce such concepts into a discursive affective framework.

The aim of this article is to explore the affective practices involved in the engagement in, and response to, humorously framed sexist and violent taboo-breaking talk, and how this in turn indexes masculinities. By focusing on how affect is stimulated, performed, and negotiated in interaction, we investigate how the participants express both desire and discomfort for what is taboo, and create a pleasurable moment by taking part in what is forbidden.

DATA AND METHOD

The data for this study consists of a recording of the livestream of an infamous episode of the Swedish podcast Alla Mina Kamrater – Morgon ‘All of My Comrades – Morning’ (AMK), aired on the morning of November 11, 2015. The podcast was a somewhat comically framed morning show, hosted by three male podcasters/comedians: Martin Soneby, Fritte Fritzsson, and Nisse Hallberg. The show consisted of talk and discussions between the hosts, as well as with invited guests, on various topics. In the recorded episode, two well know Swedish stand-up comedians were invited: Kristoffer Svensson (generally known as ‘Kringlan’ or ‘K’) and Simon Svensson.

The livestream was edited when it was released as a podcast, but the original recording was widely circulated on the internet shortly after it was aired, and is freely available on, for example, YouTube. The taboo-breaking talk of sexist and violent humor/threats is initiated by, and centered on, the guest Kringlan. While the podcast lasts longer (there were other guests during other parts of the show), our analysis draws on the thirty minutes in which Kringlan was present, as well as some talk between the hosts after he left. The recording was transcribed in Swedish in its entirety, using a modified version of Jefferson's (Reference Jefferson and Lerner2004) transcription conventions (see the appendix). The recording and transcript were listened to and read several times by the authors, who selected sections deemed interesting as illustrative examples of discursive affective practices in the five men's interaction. To increase the readability of the excerpts, a few instances of background talk have been removed.

In the article, we have strived to display some of the ebb and flow of the recording. Kringlan is frequently highly enraged, at one-point throwing chairs around the studio, screaming into the microphone, and spewing out explicitly sexist and violent threats. At other times, he is calmer, discussing his feelings and motivations regarding the events. We have chosen to present the excerpts chronologically, starting with Kringlan's entrance into the studio. In some places, we have chosen to omit lines with extreme sexualized threats. This was done because we believe that they do not add further to the points we want to make, and would draw unnecessary attention to the ‘shock’ aspects of the talk. Given the severity of the language shown in the excerpts that are included, the reader can assume that these omitted lines contain more, and even harsher, language in the same style.

Since the podcast was a highly publicized event, leading to discussion, debate, and outrage in many of Sweden's most influential news outlets, as well as on social media, there has not been any need for anonymizing transcripts, or requesting consent from the people present on the recording. Åsa Lindeborg, who was the head of the cultural editorial department of the Swedish evening paper Aftonbladet, and the main target of Kringlan's violent and sexualized threats, has given consent to being named in the article.

ANALYSIS

In the fall of 2015, Kristoffer ‘Kringlan’ Svensson (henceforth called Kringlan) was a somewhat successful author, podcaster, and stand-up comedian. Through his podcasts and stand-up shows, Kringlan had gained a reputation as a controversial figure, as someone who loathed what is colloquially dubbed the ‘politically correct’, and as someone who was not afraid of conflicts or controversy. One of his most respected outlets was the political satire podcast Lilla Drevet, which Kringlan produced along with several well-known left-leaning comedians and feminist cartoonists.

On the morning of November 11, the podcast AMK began livestreaming, and Kringlan arrived at the studio soon after the show had begun. According to himself, he was at the time intoxicated, having stayed up all night, drinking an entire bottle of grappa. The reason he did this was that the Swedish evening paper, Aftonbladet, had published a review of one of Kringlan's books, which included a short passage criticizing the Lilla Drevet podcast. Aftonbladet was also Lilla Drevet's publisher. By his own account, Kringlan was enraged by this review. His anger was directed mainly at Åsa Lindeborg, head of the cultural editorial department of Aftonbladet, and thereby the person ultimately responsible for publishing it. He had read the review late in the evening, and during the night, he had launched a series of sexist tweets at Lindeborg, and this tirade continued verbally once Kringlan arrived at the AMK Morgon studio.

Enter Kringlan

The show had been going for a few minutes (during which the group had been talking about a kidnapping drama) when Kringlan entered the room.

As Kringlan enters the room, late for the beginning of the livestream, he excuses himself in a rushed voice. His entry and excuse is immediately narrated by Martin (line 20), who constructs Kringlan as laughable because of his rushed appearance. Kringlan apparently gets stuck in the door handle, and the room explodes with laughter. His funny entrance fills the room with joy. The joint laughter is an affective practice that creates a sense of belonging. The joyful emotions, produced by the funny entrance, work in Ahmed's (Reference Ahmed2004) terms as a social glue that bring subjects into being. Here, and in the lines that follow (21–29), it can be seen how Kringlan is interpellated (Althusser Reference Althusser2001) as the clown of the group, a speech act where he is given a position and a name—being likened to the character Cosmo Kramer in the 90s comedy show, Seinfeld, well-known for his hasty and clumsy entrances. This interpellation of ‘the clown’ position is one that Kringlan responds to, and enacts repeatedly throughout the show. The men jointly construct Kringlan as the comic figure: Martin's comments in lines 25–26, together with Fritte's reply “We can call him Cosmo K Svensson!” (line 27) and Nisse's “Wow!” (line 29) bring the clownish Kramer-figure into social existence. Later in the show, Kringlan will engage in a type of hyper-performativity of this position. It can be argued that being placed in such a position alleviates some responsibility for adhering to social norms—the clownish and buffoonish style of this character is one that can act in outrageous, yet humorous, ways.

The scene is also set for what will be the main subject of conversation for the rest of the show: Kringlan's affects that are continuously scrutinized, narrated, evaluated, and laughed at. Kringlan's rushed and eager manner is here evaluated by, especially, Martin, when repeating “you really don't have to be in such a hurry” (lines 30, 32). This could be understood in relation to Scott Kiesling's discussion of a ‘masculine ease’ in American fraternities, one type of hegemonic masculinity that creates desire for men to feel ease (rather than to merely perform ease; Kiesling Reference Kiesling2018). Martin's words may be understood as a display of ease and coolness, as he is suggesting that Kringlan should not be rushed when he is late for a live-broadcast radio show. At the same time, Kringlan is constructed as laughable, because he is displaying too much eagerness, clumsiness, and lack of composure.

The burst of shared laughter by several of the participants (line 33) underlines this point. The laughter can be understood as an affective practice that does disciplinary work (Billig Reference Billig2005), in the sense that it delivers the message of Kringlan's affective norm transgression. This type of ridicule, or friendly banter, may in that sense be understood as producing desirable subjectivities by making the social order, and breaches of it, visible through laughter (even at seemingly banal humor). Kringlan is ridiculed, in particular, for caring too much, being too eager. At the same time, his norm transgression creates an enjoyable moment for everyone who can laugh together.

The first breach of taboo

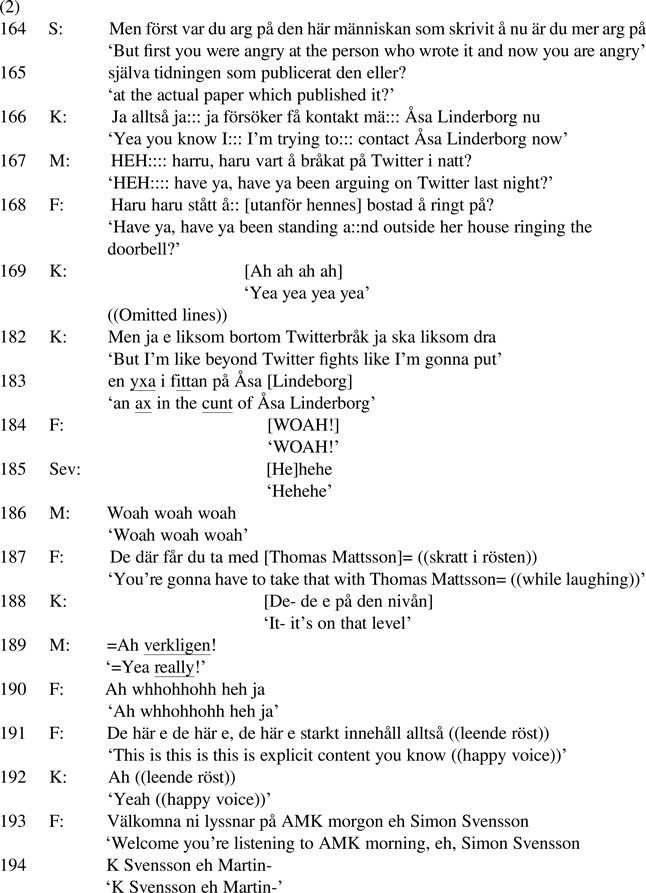

Soon the conversation turns towards ‘what happened last night’, and it is established that both Simon and Kringlan are still drunk. This information is met with great joy and excitement, and Simon begins to tell a story about how Kringlan became very angry the preceding night, as he read the review while in a taxi, and Simon tells the story humorously, with the other participants laughing and joining in with jokes, and encouragements for Kringlan to talk more. In the excerpt below, Kringlan has just explained that his anger is mainly aimed at Åsa Linderborg and Aftonbladet for publishing an article that included critical comments about his podcast Lilla Drevet, when Simon poses a critical question.

During the unfolding of the story, Kringlan recurrently produces accounts within a serious frame, explaining why he is angry, and that he, from now on, will refuse to publish the Lilla Drevet podcast via Aftonbladet. His accounts are mainly met with excitement and responses produced in a nonserious, playful frame. In lines 164–65, Simon can be seen questioning Kringlan's affect, constructing it as irrational by pointing out that Kringlan has shifted his affective focus from the reviewer to the publisher. Kringlan, however, ignores the critical undertone of Simon's question. His response is notably serious (lines 166), using a voice of reason, as he claims that he is trying to contact Åsa Lindeborg, seemingly to discuss the incident. This factual, low-investment response also constitutes a type of stance-taking, of masculine ease (Kiesling Reference Kiesling2018), a stance that he was mocked for not enacting in excerpt (1).

In contrast, Martin and Fritte's voices (lines 167–68) are ripe with excitement and anticipation at what is to come. Their teasing statements position Kringlan affectively as an angry, uncontrolled maniac, furiously ringing someone's doorbell in the middle of the night. This is for fun. The participants jointly express amusement at Kringlan's clownish behavior. This engagement in making Kringlan appear silly can be understood as affective practices that produce social relationships in the group. While these are humorous and exaggerated accounts (and thus in a sense ‘non-serious’), it is clear that the affective practice is a ‘joint intersubjective enterprise’ (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2012:83). Both the comments “have ya been arguing on Twitter last night?” (line 167) and “have ya been standing a::nd [outside her] house ringing the doorbell?” (line 168) call for a narrative that Martin and Fritte want to hear more of. The conversation is continuously guided toward affects of enjoyment, as well as anger. This can be seen in how serious statements from Kringlan are reworked and treated as either aggression or humor (or, mainly, as both: laughable aggression). We argue that Kringlan is not just interpellated as a specific position, the clown, but is also called to perform certain affects.

Kringlan, indeed, responds to the previous statements by producing a highly affective account. He is answering to the interpellation, performing the affect he was just positioned into and teased about. In a sense he is hyper-performing it: “But I'm like beyond Twitter fights like I'm gonna put an ax in the cunt of Åsa Linderborg” (lines 182–83). The statement is ambivalent, in the sense that it is produced with a straight (but rather angry) face; there is no happiness or laughter in his voice, but at the same time, the aggression and vulgarity of the words are sudden and diverge from the conversation in an absurd manner.

The other participants respond immediately with a displayed combination of shock and excitement. The interjection “woah” (lines 184, 186) can be understood as an expression somewhere in between ‘wow’ (conveying excitement or admiration) and ‘stop’ (conveying rejection or dismissal). The participants can be heard laughing or giggling, while simultaneously expressing disalignment from Kringlan's statement. Fritte, while laughing, refers to a person he presumably thinks is Åsa Lindeborg's boss, implying that Kringlan's words might be too extreme, and Martin agrees to this with emphasis (lines 187, 189). While the words uttered by Kringlan are undoubtedly highly transgressive, there is simultaneous excitement and enjoyment in the others’ voices and laughter, something that somewhat mitigates the hostility and seriousness of the situation. The others’ laughter constructs Kringlan's words as comical and laughable, rather than as something to be feared or chastised, which then, is a way of further encouraging—asking for more. At the same time, they are distancing themselves from the forbidden words and taboo subjects. These complex and, in part, contradictory affective practices both work to make sense of Kringlan's outburst, and to position the participants in the podcast studio.

Kringlan's taboo-breaking affective practice could be seen as increasing the demonstrated excitement and enjoyment in the others—there is a desire for what is forbidden (Billig Reference Billig1999). They can thus be seen as enticing or coaxing out Kringlan's ‘craziness’—and they get more than what they asked for—a breach of taboo which they receive with great pleasure. The participants are, in a sense, goading Kringlan forward, displaying ambiguous positions towards his anger, but with a desire to have him further explore a space of taboo subjects. In sum, the affective practices engaged by the participants are interactive. Affect resides not just in one person, but in its discursive formation and negotiation in specific contexts.

Unlaughter and upgrading breaches of taboo

As we have seen in the previous excerpt, Kringlan's affective work is met with ambiguous, yet curious, responses. Such responses should also be understood as affective practices in themselves, being unavoidably discursive ways of managing affect in this situation. This goes for much of the conversation, where the participants take up varying positions vis-á-vis Kringlan's narrative, where some attempt to pry further into his anger, while others question it, or try to dampen the most explicitly violent misogyny. In the following lines, the participants question Kringlan's angry reaction.

Simon's critical questioning of Kringlan's anger is posed within a serious frame—there is no laughter in his voice; he uses a voice of reason, rather (lines 270–74). It is a question that simultaneously evaluates Kringlan's affect negatively (as something that has no rational ground), and encourages him to continue his angry rampage. Kringlan responds with a slightly angry tone in his voice, as the first step in a series of upgraded sexualized insults/threats towards Lindeborg (line 275). The response from the other participants is a type of cumulative unlaughter (Billig Reference Billig2005). Simon's laughter in line 276 is quiet and somewhat held back, in a tone of disbelief. When Kringlan upgrades his threat in line 277, it appears that he has now gone too far—while the participants’ prior laughter can be seen as a challenging of conventional taboos and lines of moral indignation, there is nonetheless a limit, even for these comedians, where transgression as comedy stops, and actual transgression of a moral border commences. The others begin to suppress their previous laughter. Through unlaughter (Billig Reference Billig2005), and through the doubtful comments “yeah alright?” and “okay?” (lines 279, 280), Kringlan's behavior is being disciplined by his podcast colleagues. Put differently, efforts are made in interaction to repress the tabooed topic (Billig Reference Billig1999). However, this discursive work of repression is not very successful. In the omitted lines, Kringlan expands and further upgrades his sexualized threats. Again, Fritte can be seen as attempting to draw a line for what is acceptable at this point (lines 294–96). He can also be seen as expressing concern for the words Kringlan uttered, and the risk of being contaminated by the aggressive and sexist form of masculinity they index. Depending on the positions taken in regard to the transgressive talk, different subjectivities are constructed. Martin, by contrast, takes the opposite position, that this should not be edited or hidden away, produced in a somewhat aggressive tone (line 297).

Kringlan follows Martin's statement with a mock alignment, seemingly agreeing and continuing Martin's argument by using the same slightly aggressive and excited tone. He is thereby simultaneously mocking Martin's standpoint, by putting words in his mouth, associating him with the sexist and aggressive talk: “the whore's gonna die!” (line 299). What could possibly be understood as a statement in favor of freedom of speech, and a rejection of all form of censorship, is here humorously turned to a call for sexist threats. Kringlan is thus both mocking Martin and further positioning himself as an uncontrolled, angry, and clownish figure. This is successful, in the sense that it draws loud laughter from the participants in the room. Notably, while Kringlan's utterance in line 299 is a continuation of his threats, it is nonetheless delivered with a comedian's sensibility, to both shock and timing relative to the conversation. At the same time, someone laughingly exclaims “what the hell” (line 301), in an expression of disbelief, which is both disaligning from Kringlan, and simultaneously expressing enjoyment in the taboo-breaking conversation.

This excerpt exemplifies the waxing and waning of affect in interaction, and the continuous flow of joy/excitement, aggression, and now also, as Kringlan appears to have gone too far, concern. These affective practices involve negotiating contradictory ideologies (Billig, Condor, Edwards, Gane, Middleton, & Radley Reference Billig, Condor, Edwards, Gane, Middleton and Radley1988) in interaction. Here, on the one hand, freedom of speech and the pleasure of aggressive humor, and on the other hand, what can be understood as a Swedish gender-equal ideology, where there are limits as to what aggressive and sexist words can be uttered, and experienced as funny. In relation to this dilemma, the affective practices display both desire and fear in interaction. Desire for that which is taboo, and fear of being contaminated by it.

Dismissing discomfort

A few minutes later in the podcast, there are more discussions and questioning of Kringlan's reasoning and affect. In (4) below, there is a certain dynamic to the ways in which anger is displayed, with Kringlan mixing reasonability with sudden bursts of affect.

As previously noted, several of the people in the studio display a rational tone when talking to Kringlan. At the same time, it is a conversation that attempts to move the narrative along, one in which the participants attempt to examine his anger further. There is an eagerness, expressed in Fritte's question (lines 319–20), to find out what lies beyond, thus he continues to goad Kringlan along, without risking being placed alongside him in the conflict. Instead, he displays a tone of distanced observation and analysis of the events.

In this instance, it is Fritte who is questioning Kringlan. He is clearly not simply inquiring about Kringlan's reaction, but also, by his choice of words, and by juxtaposing the description used for Kringlan's podcast in the review: “whiteboard satire” with Kringlan's reaction “horribly angry”, he produces a critical moral evaluation of Kringlan's affective reaction as being disproportionate.

Simon aligns with Fritte (line 321), further emphasizing that the critique in the review could not be that harsh, since the possible insult does not even make sense (whiteboard satire is a derogatory neologism that does not have an established meaning). This exemplifies the critical evaluation of Kringlan's affect that the men in the studio continually engage throughout the podcast. However, while the critical questioning serves as a means of disciplining Kringlan, downgrading his affective reaction, and distancing the others from him, it simultaneously encourages and promotes his anger and affective outbursts.

Kringlan is continuously moving in a flow of shifting affective practices involving both seriousness and anger. Here, in a moment of rational and seemingly serious talk (lines 322–23, 325), he produces a more nuanced account of why he is angry, or perhaps even hurt, even though the review was not completely negative. However, this account quickly develops into another outbreak of enragement, as Kringlan moves back into sexualized insults and intense affective outbursts as he screams, seemingly at the top of his lungs, to the point of causing crackling in the microphone (lines 331).

In the immediate moment after Kringlan's outburst, the relaxed atmosphere that was there just seconds before is now gone, and when Fritte speaks, it is completely silent around him. At this point, Fritte launches a series of explicit attempts to stop Kringlan, by displaying both discomfort and worry—his stuttering, hesitant, yet slightly happy voice, somewhat tainted with nervousness (lines 333–35). Again, Kringlan moves quickly to the next affective practice, displaying a comedic timing, something that often gets the greatest appreciation from the rest of the participants during those occasions where he can show his improvisational skills as a comedian. This skill is exemplified here, as he follows the enraged scream into the microphone by talking to Fritte about wanting a more nuanced debate (line 336). He is successful in that he draws laughter from the group.

This excerpt also shows examples of attempts at displaying genuine concern over the contents of the podcast, with Fritte repeatedly complaining both directly to Kringlan (lines 329, 333–35), as well as to the rest of the participants (line 340). However, it is clear that the participants orient to various and contradictory goals here, and that the humor practices are intertwined with negotiations of ideological dilemmas. It is significant that Fritte is repeatedly ignored by both Kringlan and the other participants, and his displayed discomfort and concern is dismissed. Martin, by contrast, seems to be the one most eagerly anticipating what Kringlan will say, explicitly giving positive assessments of the podcast content (line 343). This does not mean that he agrees with what Kringlan says, but rather, that the situation produces valuable content for the podcast, and Martin's enthusiastic voice is ripe with excitement. In Fritte and Martin's contrasting attitudes towards Kringlan's tirades, both repression and transgression can be seen and understood as discursively constructed and maintained. Fritte's attempts to subdue the worst of Kringlan's outbursts are overcome by Martin's desire for moving past such repression and transgressing what is socially accepted.

Attempts to end the conversation and urges to continue

The conversation continues for another six minutes, as the participants continue to question Kringlan's reasoning and affect, that is, distancing themselves from Kringlan's anger and aggressive talk, while simultaneously encouraging him to continue with it, and thereby giving them more of the same sort of transgressions. Kringlan delivers on this, giving at least two more very violent and misogynistic narratives along the same tangents as before. But Kringlan also displays ambivalence. Below, he responds to Nisse's suggestion that they make a deal that during the second half of the podcast, when another guest will arrive, that they will not talk about Åsa Lindeborg anymore. Kringlan agrees.

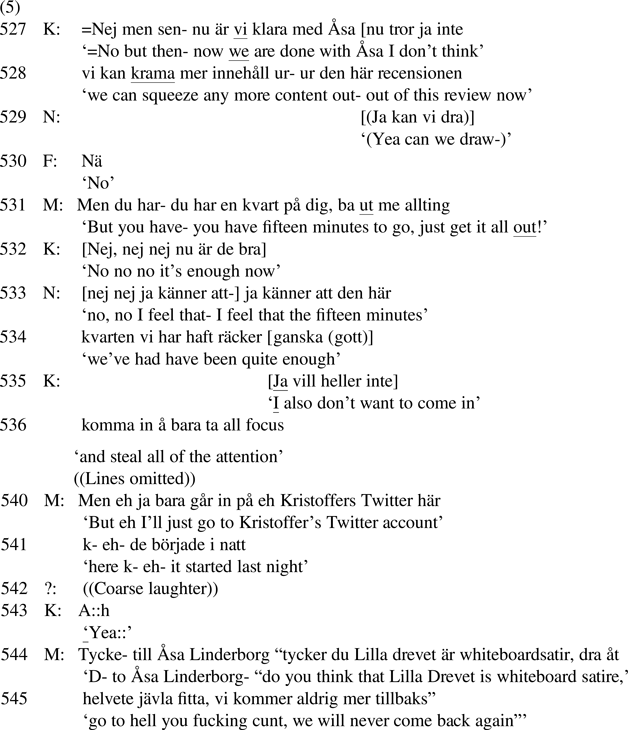

As we have seen so far, Kringlan's transgression through affective practices is an ongoing theme throughout the podcast. Yet, the affective practices can also be understood as a collective enterprise, but working in multiple directions. The group's responses to Kringlan are ambivalent, in that their questions and comments simultaneously dismiss and encourage. Kringlan himself also displays ambivalence, and at times he makes attempts to finish the conversation, as he does in this excerpt. He responds to Nisse's (disciplinary) suggestion by agreeing that they are done talking about Åsa Lindeborg, and, with a slightly condescending tone of voice, comments that they cannot squeeze any more out of this story now, suggesting that they have taken this as far as they could. At the same time, it shows some of the rationale behind the discussion—the necessity to provide the podcast with interesting content.

Nisse, Fritte, and Kringlan all cooperate in agreeing that the subject is finished, while Martin resists by attempting to engage Kringlan in continuing (line 531). Notably, he is encouraging Kringlan to enact anger, and for his own good: “get it all out”. Both Kringlan and Nisse persist, Kringlan by humorously referring to the earlier talk about him stealing all of the attention. Now, after fifteen minutes of intensive and affective talk about his anger, and hyper-performing the position of uncontrolled clown he then was given, this appears even more absurd as a self-reflective statement. At this point, the affective setting is light and cheery.

Martin, however, does not bend and instead turns to reading Kringlan's words from Twitter (lines 544–45), using reported speech that allows him to utter those taboo words, without having to be associated with them himself (in a manner that appears to be pleasurable, according to his eager tone). These turns produced by Martin can be understood as practices that promote affect: explicit urges for Kringlan to continue and requests for him to express even more rage. Finally, the reported speech (Martin's use of Kringlan's own words) can be seen as a way to get more, even as Kringlan refuses to contribute. These are upgraded, and successful, attempts at promoting more affect. Directly following this excerpt, Kringlan remains silent for a few turns, giving only very short responses, then suddenly changes the subject of the conversation by directing his anger toward the (male) author of the review, and successively launching a series of violent threats towards him (this however, is outside the scope of this article to analyze).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Listening to the podcast for the first time, listeners may be taken aback by the harshness of the language, and the display of unrestrained misogyny, all coupled with its relentlessness; the recording is thirty minutes long. During the course of the podcast, Kringlan's rage waxes and wanes, but never entirely dissipates. One might argue that what is most striking is Kringlan's performance of a threatening masculinity through talking oppressively about women. This was precisely what became the focus of discussion during the aftermath of the podcast, in an intense debate about the manner in which the other men in the podcast studio supported, actively and passively, Kringlan's threats of rape and violence. This also led to severe consequences for the people involved: Kringlan lost his book contract, left the Lilla Drevet podcast, and had most of his work cancelled. AMK Morgon lost major sponsorship deals, and the podcast was cancelled soon afterwards. In all, these were clear expressions of a massive dismay that the participants in the podcast studio did not stop Kringlan's performance of a sexist and misogynist heterosexual masculinity.

In our analysis, we have highlighted the use of truly misogynist words, however, we argue that the podcast does not (solely) have to be understood as a performance of heterosexual masculinity, or of a misogynist man's attitudes surfacing in an inappropriate setting while under the influence of alcohol, as the public reactions suggested. Rather, we wanted to investigate the incident as an example of how a group of men, in interaction, express desire for what is taboo, and create an enjoyable moment by taking part in what is forbidden. The analyses demonstrate several interlinked aspects of this, where conflicting ideologies are negotiated in practice, and where masculine subjectivities are ambiguous and in play, not preformed, but situationally malleable.

In the interaction, we see the men's desire for taboo-breaking—transgressing the social norms of the everyday, and of conventions of social conduct. This is also recognizable as part of male, homosocial bonding over a shared breach, and interactive exploration of something ‘outside’ of what can regularly be said and done (cf. Kiesling Reference Kiesling2005). By pronouncing misogynist and violent comments in a public forum such as the live podcast, a titillating, pleasurable, and entertaining conversation is created. Importantly, the breeches of taboo here do not only involve producing forbidden utterances, but also a norm-breeching anger—a rage which, according to the other participants, is not in proportion to what happened.

Yet, the desire for what is taboo brings with it the fear of what engaging in it might lead to. In the analysis, we see different displays of fear and discomfort, from open displays of distress to attempts to calm the situation and steer the conversation toward rational discussion. Engaging in norm breaching behavior always runs the risk of being associated with it, in this case the fear (which, for the people of the AMK podcast, turned out to be valid) of being associated with the immoral masculinity that the taboo-breaches index. Being a ‘good guy’, or a cool and funny man, involves negotiating conflicting everyday ideologies, such as staying within the everyday norms where highly misogynist talk is unacceptable, while at the same time displaying a masculine ease (Kiesling Reference Kiesling2018), where matters are not taken too seriously. In the podcast, Kringlan is not simply halted, but the participants also display that they are aware of comedic interpretations and framing of the ongoing events. Furthermore, while transgressions make the social norms visible, this is not the same as questioning these norms. The desire appears to be aimed at being someone who can both give and take a joke, but ultimately knows his moral bounds.

This dilemma of desire and fear can be seen in the interaction, as the exhilarating topic of aggressive, sexualized violence creates ambivalence in the group. We have shown that the participants display both fear and desire—the exhilaration of moving beyond what is allowed, and the fear of what it may entail. It is, further, visible in the co-construction of affect (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2013). On the one hand, we find practices that promote certain affects, practices that induce more anger from Kringlan, and pleasure and laughter from the other men. We have shown how Kringlan's taboo-breaking narratives, anger, and threats were constantly being encouraged by the other participants’ comments: plenty of questions for more details, reminders that steer the conversation back to the subject of Kringlan's anger, lots of laughter and exclamations, explicit encouragements to let his emotions out, and, finally, the use of reported speech as a way for the other participants to ask for Kringlan to talk more. We understand this as a desire to hear more of the taboo-breaking words, and see more of the taboo-breaking rage, and to remain in the affective state of both pleasure and laughter.

On the other hand, we find practices that distance and discipline affects. The analyses show how the participants engaged in such discursive-affective practices, which produce a distancing from Kringlan's anger by laughing at it. These can be understood as examples of what Billig (Reference Billig2005) calls disciplinary laughter and unlaughter, and we also see it as a response to displayed concern or eagerness, which is continuously either laughed at or ignored throughout the podcast. Through a distancing and disciplinary laughter, or by avoiding laughter when it is expected, they manage, at different times, to disalign with both transgressive misogyny and displayed concerns over such transgressions.

Together, these different affective practices make up both (a) the co-construction of Kringlan as the crazy Kramer-clown, a pathological Other, for their joint desire of breaking taboos, and (b) a sacrificing of the clown. This is a sacrifice that works as a method for dealing with the dilemma between fear of, and desire for, transgression. Here, the group pins the thrill and desire for moral transgression to one person, who enacts the transgression on behalf of the whole group. It is the affective practices, in the group, that propel the clown forward, thus encouraging him into saying and doing more and more, while the others stay safely behind him. It opens up the possibilities of having someone in the group who is entitled to break taboos, while the others can follow in laughs and enjoyment, but also with distance, dismay, and displays of discomfort. In this manner, they attempt to avoid some of the moral taint that may fall on them. Kringlan is interpellated as the clown (with sick/crazy values, and irrational, explosive emotions) from the very start of the interaction - something he answers to and positions himself as. However, this position is also ambivalent and vulnerable, which is displayed by Kringlan, who in one moment expresses “I don't want to talk more”, while in the next upgrading his utterances to further profanities.

In conclusion, we would like to first highlight the importance of studying practices such as rape humor as not being primarily expressions of inner misogynist attitudes within individual people. Rather, we point to the need to study this in interaction, as a collective and social phenomenon. In part, the critical voices raised during the aftermath of this podcast drew on a traditional, modernist understanding of the unitary subject, with an essential inner moral. With this understanding, all hope is aimed at the individual who should stand up against evil or immorality, and make a difference. Our analysis takes a different perspective, and demonstrates how affect, rage, and misogyny are not simply owned or cast within a single subject. Rather, they are shared and discursive. Affects, like subject positions, are interpellated in social interaction. This, however, does not entail that the individual is to be understood as completely agentless.

The affective analysis of transgressive humor in interaction thus helps us understand the subjective experience of living out cultures of masculinities, by illuminating the intricacies of affective practices, as well as the plurality and complexity of subjectivities. While subjectivities are ‘ready-made’, familiar, and transpersonal, they also come in the plural, are shifting, and often clashing (Wetherell Reference Wetherell2012:125). Various subject positions may, at one point, be a source for ‘invested identity’, and at another point, be a resource to position oneself against (Wetherell & Edley Reference Wetherell and Edley1999:351). The push and pull of both pleasure and fear surrounding the instances of rape humor, and the complexity of these affective practices, illuminate how individuals are captured by social forces, yet in a way that does not override agency. As Wetherell writes, affective practice ‘comes into shape and continues to change and refigure as it flows on’ (Reference Wetherell2012:15). We see this, for example, in the moments of nonlaughter and disalignments.

Second, we argue for the fruitfulness of studying affect as a discursive phenomenon. We have followed Wetherell's (Reference Wetherell2012) call to treat affects as intertwined and inseparable from social interactions and discursive practices. It is exactly through these practices that affects are made meaningful. In this article, we have suggested a combination of Wetherell's discursive perspective on affects, and a return to some seminal texts on desire, repression, and taboo, as well as on humor, to understand what affects do, as Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2004) asks us. Through including explicit language in an analysis of fear, anger, and desire, we contribute with an analysis on both subjectivity and co-construction of affect in interaction.

APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS

- :

prolonged syllable

- [ ]

overlapping utterances

- (.)

micropause, i.e. shorter than (0.5)

- (yes)

unsure transcription

- YES

relatively high amplitude

- (())

transcriber comments

- ?

rising terminal intonation

- after

sounds marked by emphatic stress

- -

abrupt cut-off

- underline

emphasis

- =

continued from prior utterance without gap