I. Introduction

Wine tasting is a complex and ambiguous experience, as objective measures of product quality are not easy to evaluate (Almenberg and Dreber, Reference Almenberg and Dreber2011). However, wine tastings can spark interesting conversations, especially commercial insights (Bodington, Reference Bodington2012). Studies have found that tasting results are influenced by expertise, preferences, and the reviewer’s gender (e.g., Castriota et al., Reference Castriota, Curzi and Delmastro2013). As a result, wine quality is an abstract measure that is difficult to define in absolute terms (Cao and Stokes, Reference Cao and Stokes2017). Rankings and ratings of wines are typically provided by the conversion of professional judges and reviewers (e.g., Ashenfelter and Quandt, Reference Ashenfelter and Quandt1999). Ranking refers to the arrangement of the objects according to some characteristic, such as from largest to smallest or vice versa (Olkin et al., Reference Olkin, Lou, Stokes and Cao2015). Rating entails grouping items into categories based on shared characteristics (Olkin et al., Reference Olkin, Lou, Stokes and Cao2015). Given the significant rise in the number of experienced wine tasters, it is imperative to understand how professional judges and reviewers are impacted by given information (i.e., grape variety, wine color, and reviewer’s gender) during blind tastings (Wang and Prešern, Reference Wang and Prešern2018).

Additionally, sensory qualities, winery reputation, country of origin, and grape varieties indicate product quality (e.g., Oczkowski and Doucouliagos, Reference Oczkowski and Doucouliagos2015). Grape varieties especially play a unique role in the wine industry in the context of wine reputation and branding. According to Steiner (Reference Steiner2004), consumers regard grape varieties in addition to wine regions as proxies for brands. The grape variety is recognized as an essential determinant of wine quality (for a comprehensive overview, see Outreville and Le Fur, Reference Outreville and Le Fur2020), which can affect the flavors and aromas of the wine. Thus, we assume that grape varieties act as quality parameters to which a particular reputation is assigned.

This study aims to determine whether a grape variety’s name’s linguistic properties contributed to the implicit transfer of gender-associated traits and the explicit quality assessments of professional judges and reviewers. The current study investigates the hypothesis that consumers prefer and have higher opinions of products with feminine names, which would result in higher ratings and more favorable reviews. By mapping ordinal scaled values to phonetic properties of names (Barry and Harper, Reference Barry and Harper1995), Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021) show that names with a high femininity score receive higher ratings and more positive evaluations than products with a high masculinity score. By analyzing professional wine assessments by a critics’ network consisting of female and male reviewers, this study also provides evidence that people’s perceptions and assessments can be impacted by gender bias. Hence, we are interested in investigating whether female and male judges respond differently to phonetic name traits, potentially influencing the overall ratings and rankings of wines. Klink (Reference Klink2009) has shown that women and men respond with different preferences to gendered language, indicating gender differences in reactions to phonetic name properties. Therefore, we address the following research questions:

1. How do phonetic name traits impact wine ratings, assuming that specific wine characteristics are known in the professional evaluation process?

2. Are female and male reviewers potentially attracted to different phonetic name traits, which affects the overall product rating?

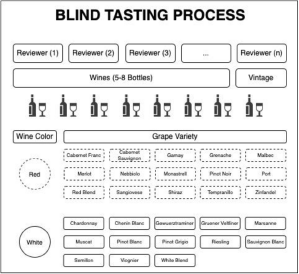

We address these research questions in a quasi-experimental setting by examining the known parameters in a blind wine tasting on the first stage of the professional review process. Blind tastings take place in groups of five to eight wine samples each, with the producers of the wines and their prices kept secret. The tasters may know general information about a sample, such as its varietal and vintage. They still don’t know who makes a particular option or what the suggested retail price is. Because the wines were presented blind, participants were not influenced by information about the wine’s origin, label, or price, allowing us to track preferences based solely on the wine’s inherent characteristics. The blind tastings possess all characteristics of a quasi-experiment to establish a cause-and-effect relationship as the reviewers are pre-selected and assigned to specific wine-origin countries, with only a little information provided in the review process. The professional rating score is our variable of primary interest.

We find a significant phonetic gender gap in wine ratings, i.e., female grape varieties receive lower ratings. Heterogeneity analysis by reviewer gender reveals that this penalty depends on both the color of the wine and the gender of the reviewer. In particular, white (red) wines with more feminine names receive lower ratings from women (men). This suggests that both women and men assign a phonetic penalty to the type of wine they generally know or like better (white for women, red for men). We also find that women, on average, rate wines lower than men.

Our study contributes to current research in several ways. This study sheds light on assessing product quality in blind tastings and their potential (gender) biases. Moreover, we aim to investigate the extent to which phonetic traits suggest product attributes in the context of professional reviews and, for this purpose, analyze parameters known to reviewers, such as grape variety. To the best of our knowledge, the impact of this phonetic terminology has not been investigated in the context of wine ratings. Thus, this study aims to close this research gap and investigate how product variety and phonetic name traits affect expert ratings.

Furthermore, we contribute to current research by investigating potential gender bias related to known determinants in the blind tasting review process. The results support the importance of inherent product qualities in wine tasting and ratings among wine producers, enthusiasts, and critics. With these insights, e.g., winemakers, producing firms, wine experts, and wine critics are able to gain further insights into unconscious wine-tasting mechanisms in the wine industry that could affect the evaluated wine quality and, thus, the reputation of wines and wineries.

II. Literature and hypotheses

Previous research has demonstrated that the phonetic patterns of names affect product information, consumer behavior, and even pricing (e.g., Klink, Reference Klink2001, Pogacar et al., Reference Pogacar, Plant, Rosulek and Kouril2015). The association of phonetic patterns and inherent product qualities is known as phonetic symbolism (Keller and Lehmann, Reference Keller and Lehmann2006). Market participants unconsciously process these associative perceptions, which affect their judgment of names without conscious awareness (e.g., Yorkston and Menon, Reference Yorkston and Menon2004, Pogacar et al., Reference Pogacar, Shrum and Lowrey2018). The association of specific product attributes over phonological properties has been investigated mainly in experimental studies (e.g., Arora et al., Reference Arora, Kalro and Sharma2022). Following Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Klink and Guo2013), phonetic symbolism creates brand personalities in that names with front vowels indicate a more feminine brand personality, while names with back vowels construct a masculine brand personality. Moreover, Klink (Reference Klink2009) shows that females prefer the two front vowels [i] and [e], while males prefer the two back vowels [o] and [u]. These studies apparently reveal specific gender-specific preferences for names. At the same time, product characteristics can be evoked by these phonetic structures, which can also be transported as quality-indicating characteristics in wine consumption. For instance, we assume that qualities such as lightness could also be associated with a particular grape variety or wine color.

a. Phonetic gender score

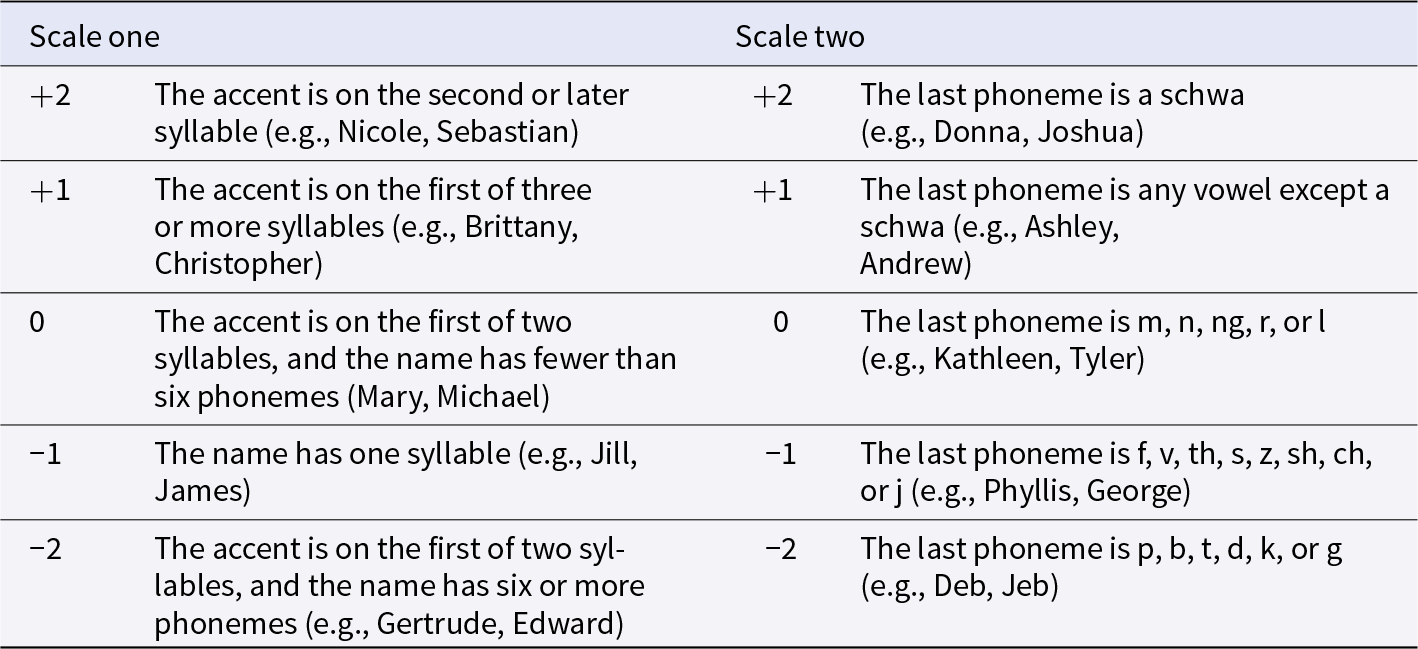

Men’s and women’s names have distinguishable patterns; thus, individuals learn to discern linguistic gender indicators in names (Barry and Harper, Reference Barry and Harper1995). Barry and Harper (Reference Barry and Harper1995) devised a phonetic gender score, a quantitative scale based on a name’s length, sounds, and stress that has been used to measure the degree to which a name is feminine or masculine. The phonetic gender score helps determine if a novel or unfamiliar name is feminine or masculine. The phonetic gender score is the sum of two quantitative scales, ranging from −2 (very masculine) to +2 (very feminine). Names with positive scores are predominantly feminine. Names with negative scores are predominantly masculine. One scale measures the phonetic traits of the entire name. The other scale measures phonetic traits of the last phoneme (i.e., the characteristics of a single sound). This normative scale is based on American male and female given names. The phonetic gender scores can be applied to a wide variety of names, other ethnic groups, and different languages (e.g., Latin, French, Spanish, German, and Russian), and consumer products, boats, houses, streets, cities, etc. (Barry and Harper, Reference Barry and Harper1995). With later research, it has conceptually been validated (e.g., Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Kelly and Sharoni1999, Slepian and Galinsky, Reference Slepian and Galinsky2016, Whissell, Reference Whissell2001). Table 1 summarizes the phonetic gender score utilized in the present study (see Barry and Harper Reference Barry and Harper1995).

Table 1. Phonetic gender scoring system (based on Barry and Harper Reference Barry and Harper1995)

Phonetic gender score = the average of scales one and two.

A study by Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021) examines how brand names express gender connotations and how this affects performance, choice, and attitudes. It shows how linguistically feminine names improve perceived comfort and brand performance. However, they show that the benefits of feminine brand names are diminished when the products are utilitarian and the average user is male. Additionally, some studies illustrate how gender implications affect names and inherent qualities, in which femininity is associated with attributes such as softness, lightness, and mildness. In contrast, masculine names are associated with opposite qualities (e.g., Klink, Reference Klink2000). Moreover, Guevremont and Grohmann (Reference Guevremont and Grohmann2015) have shown that name consonants affect consumers’ perceptions. Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021) have shown that feminine brand names are positively associated with more favorable attitudes and increased consumer choice. Masset et al. (Reference Masset, Terrier and Livat2023) have analyzed over 1400 expert tasting notes and found that more feminine wines receive similar ratings and sell for similar prices as their more masculine counterparts but are perceived as having limited aging potential.

Names are frequently employed in the wine industry to inform customers about the qualities and features of various wines. Motivated by the results of Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021), we test whether linguistically feminine names—often associated with positive qualities—receive higher ratings. As a result, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H1: Higher phonetic gender scores, and therefore more feminine names, will receive higher ratings.

b. Gender-specific choices

There are distinct disparities between men’s and women’s wine-drinking habits and sensory preferences. Mora et al. (Reference Mora, Urdaneta and Chaya2018) have shown that men and women differ in their emotional responses to wine. According to Bruwer et al. (Reference Bruwer, Saliba and Miller2011), women show specific preferences for wine consumption. They have found that women consume white wine more often than men and prefer wine with a higher sweetness, preferring medium-bodied wines to light or full-bodied ones. Further, they state that female consumers favor sensory qualities such as fruit aromas, fragrances, vegetal flavors, woody aromas, and palate sensations. At the same time, men attach importance to the aged qualities of the wine.

According to Ough and Amerine (Reference Ough and Amerine1970), women prefer red wines with brighter hue intensity than males. Bartoshuk (Reference Bartoshuk2000) finds that women are more likely than men to have high densities of specific types of sensory cells on their tongues, making them so-called supertasters. According to Laeng et al. (Reference Laeng, Berridge and Butter1993), men rate sweet drinks higher than women. Bodington (Reference Bodington2017) finds minimal variation in the relative wine preferences of men and women. This finding could be attributed to taste physiology and psychology similarities and factors such as cultural milieu, experience, education, and self-selection toward a wine interest. Sena-Esteves et al. (Reference Sena-Esteves, Mota and Malfeito-Ferreira2018) state that women prefer sweeter red wine than males. Using an online poll, Ristic et al. (Reference Ristic, Danner, Johnson, Meiselman, Hoek, Jiranek and Bastian2019) report variations in hedonic and emotional responses to wine scents between men and women.

On the other hand, Pickering and Hayes (Reference Pickering and Hayes2017) discovered that women’s wine type preferences differed from men’s for dry sparkling and dry sherry wines. In addition, previous studies have shown that feminine names appeal to women, especially for feminine products (e.g., Yorkston and De Mello Reference Yorkston and De Mello2005). Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021) demonstrate that both men and women prefer feminine names and are just as attractive as masculine names for products used by males. These studies suggest that men and women tend to vary in their gustatory preferences for wine consumption, resulting in a potential gender bias concerning reviews of wines. Therefore, gender biases may affect how consumers perceive and evaluate experience goods, whether through associated product attributes or specific taste preferences.

Furthermore, studies demonstrate that brand names that correspond to the usual user’s gender are more well-regarded than those that don’t (e.g., Yorkston and De Mello, Reference Yorkston and De Mello2005). As a result, gendered language and, thus, the phonetic gender score may also be moderated by the reviewers’ gender. Therefore, we hypothesize that the reviewer’s gender is a boundary condition to the perceived phonetic name and, thus, the feminine name advantage. Thus, we state the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H2a: Females give wines with more feminine names (thus, higher phonetic gender scores) higher ratings compared to males.

Hypothesis H2b: Feminine-gendered names are preferred by women more than men, while masculine-gendered names are preferred by men more than women.

c. Product categories and preferences

Horowitz and Lockshin (Reference Horowitz and Lockshin2002) examined the correlations between the quality rankings of expert reviewers and the eight grape varieties, Chardonnay, Riesling, Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet, Shiraz, Merlot, and Pinot Noir, and discovered a statistically significant relationship. According to Cardebat and Livat (Reference Cardebat and Livat2016), taste preferences often consider the expert’s evaluations. Therefore, we aim to investigate the relationship between the gendered connotations of names and their effects on consumer preferences for red and white wines. They were particularly given that the reviewers can visually judge the wine color during the blind tasting process. While red wines are often attributed qualities such as “warmth” owing to their sensory characteristics (e.g., Gawel et al., Reference Gawel, Oberholster and Francis2000), warmth is associated with femininity (e.g., Brown et al., Reference Brown, Phills, Mercurio, Olah and Veilleux2018) and affective qualities such as warmth impact ratings and sales (e.g., Aaker et al., Reference Aaker, Garbinsky and Vohs2012). According to Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021), feminine names ought to improve perceived warmth and subsequent brand outcomes. Warmth is an affective reaction; thus, specific product categories are more affect-focused than others (e.g., Kervyn et al., Reference Kervyn, Fiske and Malone2012). Wang and Prešern (Reference Wang and Prešern2018) found a preference for wine age, acidity, sweetness, and especially red wines compared to white wines, even when the wines tasted blind. Brower et al. (Reference Bruwer, Saliba and Miller2011) highlight differences in sensory preferences and wine consumption behavior. Regarding sensory preferences, fruit flavors and aromas are particularly important for women, while men prefer the mature characteristics of wine. We, therefore, expect the benefit from feminine names to be more substantial for red wines than white wines because red wines are appreciated more for warmth than white wines.

Consequently, this study aims to determine whether red wines have a stronger feminine name advantage than white wines. Due to the distinctions in how consumers and reviewers view these two wine categories, we assume that the gender connotations of names and, thus, higher phonetic gender scores will affect consumer preferences for red wines more than white wines. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H3: The phonetic gender score advantage will be significantly higher for red than white wines.

III. Data and model

The dataset comprises wine reviews from wine-tasting experiments conducted for Wine Enthusiast Magazine. It includes specific data on each rated wine bottle’s country, description, winery, designation, rating points, reviews, wine price, province, and region. We obtained data on 18,609 wines professionally rated in blind tasting experiments between 2011 and 2016, yielding a sample of 31,058 individual experiment observations to objectively evaluate the influence of phonetic gender scores on quality outcomes measured by wine experts’ ratings.

The Wine Enthusiast Magazine was first published in print form in 1988. Since then, it has become a digital platform with the website www.winemag.com and various content, including podcasts, buying guides, and expert opinions. With 4.1 million readers focusing on journalism on wine and beverages, the magazine is regarded as one of the top seven wine publications in the U.S. (Storchmann, Reference Storchmann2012). The magazine also provides expert reviews of wines using a predetermined point system, which professional critics provide. According to the magazine information on their website, over 25,000 wines are tested annually as part of this professional grading system run by a network of 25 experts with specialized country-specific knowledge. The reviewers are also allocated as primary reviewers for wine regions, which elevate their status to that of authorities with in-depth knowledge of such regions.

Each bottle of wine tested receives a score between 80 and 100, where 100 is the highest quality rating. The producers of the wines and the prices are kept a secret; the blind tastings are conducted in groups of five to eight wine samples each. Reviewers may be aware of broad details about a sample, such as the vintage and variety. Still, they are unaware of any given option’s producer or suggested retail price. We are, therefore, able to track preferences solely based on the intrinsic qualities of the wine because the wines were served blind, which prevented participants from being swayed by label, price, or origin information (Wang and Prešern, Reference Wang and Prešern2018, Almenberg and Dreber, Reference Almenberg and Dreber2011).

Hence, the blind tastings possess all the characteristics of a quasi-experiment to establish a cause-and-effect relationship (see Figure 1). The reviewers are randomly assigned to different groups, which ensure that any observed effects are not due to pre-existing differences between the groups. In addition, blind tastings are standardized procedures to ensure all participants are treated equally. This helps to eliminate extraneous variables that could affect the results. As the blind tastings are conducted yearly, the results are reliable and can be generalized. Thus, the femininity and/or masculinity of the variety’s name can lead to implicit associations with wine-tasting characteristics.

Figure 1. Blind tasting process.

We primarily focus on the femininity and/or masculinity of the variety’s name and the relationship between the ratings from professional reviewers, their gender, and the wine color characteristics. Using a technique by Barry and Harper (Reference Barry and Harper1995) (see Table 1), we determined the phonetic gender score of wine types. With values ranging from −2 (extremely masculine) to +2 (highly feminine), the phonetic gender score quantifies how much a name is masculine or feminine based on its length, sounds, and stress. This normative scale is based on male and female names from the United States and has conceptual support from research (e.g., Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Kelly and Sharoni1999, Slepian and Galinsky, Reference Slepian and Galinsky2016, Whissell, Reference Whissell2001).

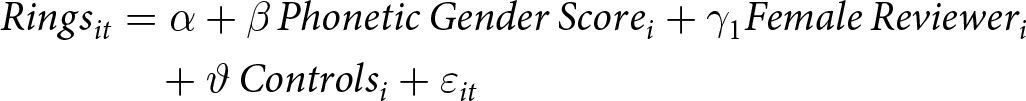

The complete list of model variables included in the regression analyses explains that brand outcome, measured by ratings for wine title i at time t, is

Model I

\begin{align}Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}\nonumber \\ & \quad + \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}\end{align}

\begin{align}Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}\nonumber \\ & \quad + \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}\end{align}Model II

\begin{align}

Ring{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i}\nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

Ring{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i}\nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}Model III

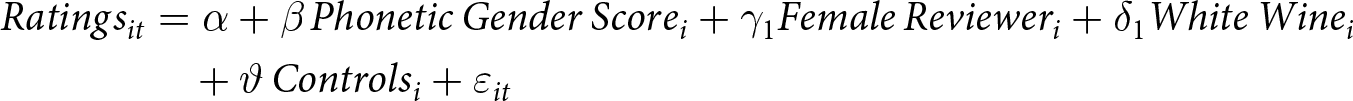

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i} + {\delta _1}White\,Win{e_i}\nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}} \nonumber \\ & \quad

\end{align}

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i} + {\delta _1}White\,Win{e_i}\nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}} \nonumber \\ & \quad

\end{align}Model IV

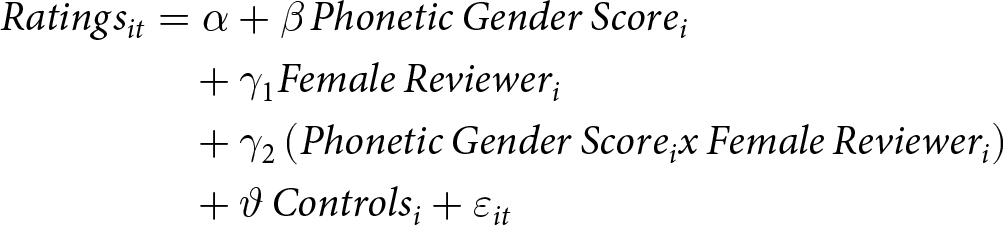

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\gamma _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,Female\,Reviewe{r_i}} \right)\nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\gamma _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,Female\,Reviewe{r_i}} \right)\nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}Model V

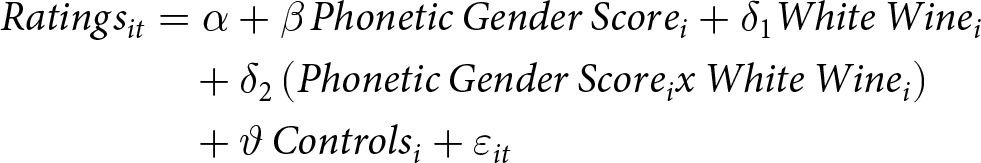

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\delta _1}White\,Win{e_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\delta _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,White\,Win{e_i}} \right) \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\delta _1}White\,Win{e_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\delta _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,White\,Win{e_i}} \right) \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}Model VI

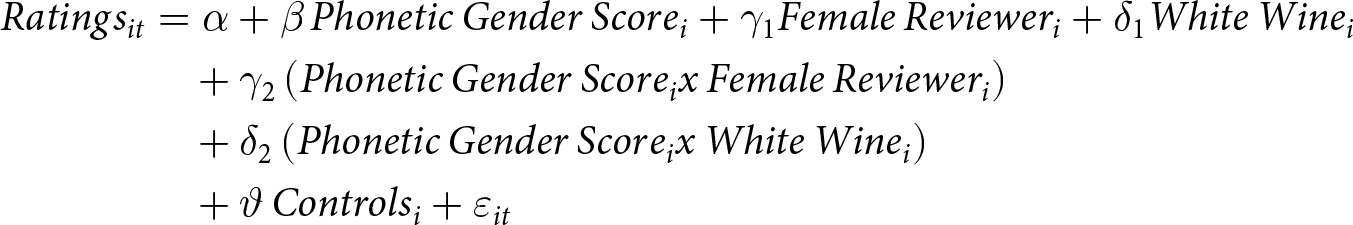

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i} + {\delta _1}White\,Win{e_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\gamma _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,Female\,Reviewe{r_i}} \right) \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\delta _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,White\,Win{e_i}} \right)\; \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

Rating{s_{it}} & = \alpha + \beta\, Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i} + {\gamma _1}Female\,Reviewe{r_i} + {\delta _1}White\,Win{e_i} \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\gamma _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,Female\,Reviewe{r_i}} \right) \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ {\delta _2}\left( {Phonetic\,Gender\,Scor{e_i}x\,White\,Win{e_i}} \right)\; \nonumber \\ & \quad

+ \vartheta\, Control{s_i} + {\varepsilon _{it}}

\end{align}where the definitions of each of these individual vectors of variables are consistent with the categories of variables reported in the descriptive statistics shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

Controls consist of country of origin, province, and winery dummies representing the country of origin and growing region of the wine i. Wine is produced in many countries with unique geographic, climatic, and growing conditions that determine product attributes. Consequently, the control dummies account for the effect of product-inherent characteristics on the taste and quality of the wine and thus on the wine ratings (e.g., Horowitz and Lockshin, Reference Horowitz and Lockshin2002).

Specifically, the values of the β coefficient allow us to test hypothesis H1, the γ coefficients allow for the testing of H2, and the δ coefficients allow for the testing of H3.

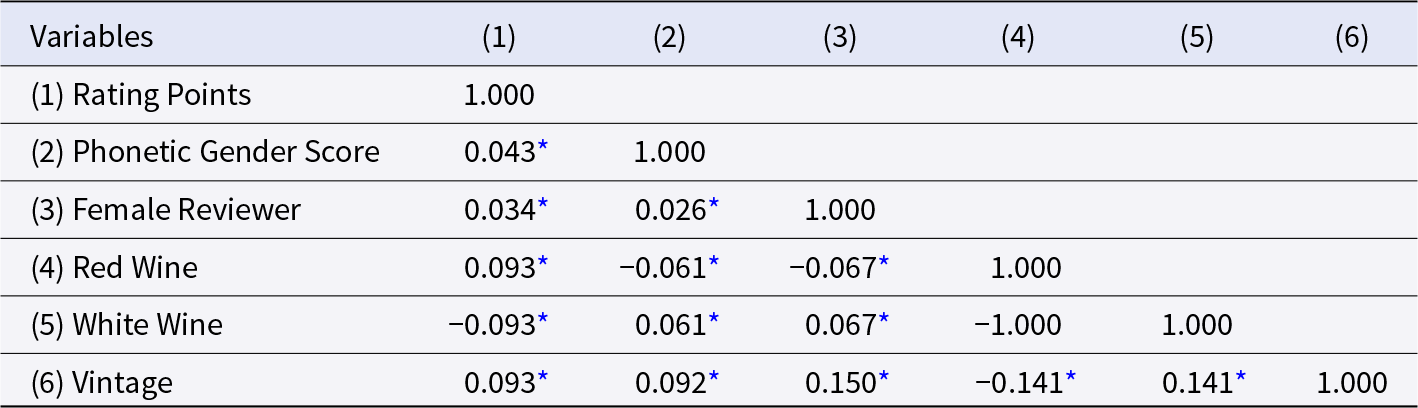

Using appropriate variables capturing product characteristics, we present correlation coefficients between the variables used in the estimations in Table 4. The highest level of correlation can be observed between the wine colors and the phonetic gender score, with coefficients of −0.15 and +0.15. Consequently, these correlation levels are well below the threshold, whereby multicollinearity would significantly affect our results.

Table 4. Pairwise correlations

* p < 0.1.

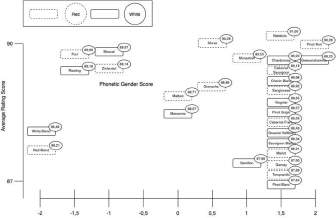

Figure 2 shows the distribution of phonetic gender scores for grape varieties and colors, respectively. We see that the distribution of scores for grape varieties is skewed to the left, with 14 grape varieties having a phonetic gender score of 1.5. However, we see that the phonetic gender scores are equally distributed across red (dashed line) and white (solid line) varieties.

Figure 2. Distribution of phonetic gender scores across grape varieties (with indication of average scores).

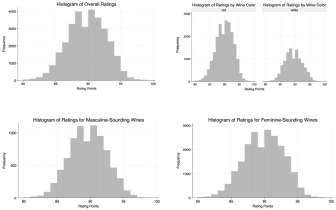

So are the average scores (seen in the tiny bubbles), which range from 87 to 92. In addition, we present histograms to provide visual representations of the distribution of ratings in different scenarios, allowing us to explore how ratings are distributed overall, across different wine colors, and based on phonetic scores (see Figure 3). This grouped histogram shows the distribution of ratings separated by different wine colors. The histograms for phonetic scores compare the distribution of ratings between feminine and masculine sounding wines (i.e., phonetic scores less than 0 are considered masculine and scores greater than 0 are considered feminine).

Figure 3. Histograms of the average rating scores.

The following section presents the estimation results and a series of alternate model specifications as a robustness check to explore a range of different interactions of signals both separately and jointly. Additionally, we check our results for validity, significance, and robustness.

IV. Empirical analysis and results

In the empirical analysis that follows, we use panel data regressions. Panel data regressions have more degrees of freedom and sample variability than cross-sectional data regressions and include intertemporal dynamics that allow for the control of missing or unobserved variables (Hsiao, Reference Hsiao2007). Since our outcome of interest, the rating points for wine i at time t, is time-varying, and our explanatory variables such as phonetic gender score, reviewer gender, or wine color are time-invariant variables, we focus on random-effects regressions to estimate variation within and between wines (Hsiao, Reference Hsiao2007). In this way, we take advantage of panel data and can deal with possible omitted variable bias due to heterogeneity in the data.

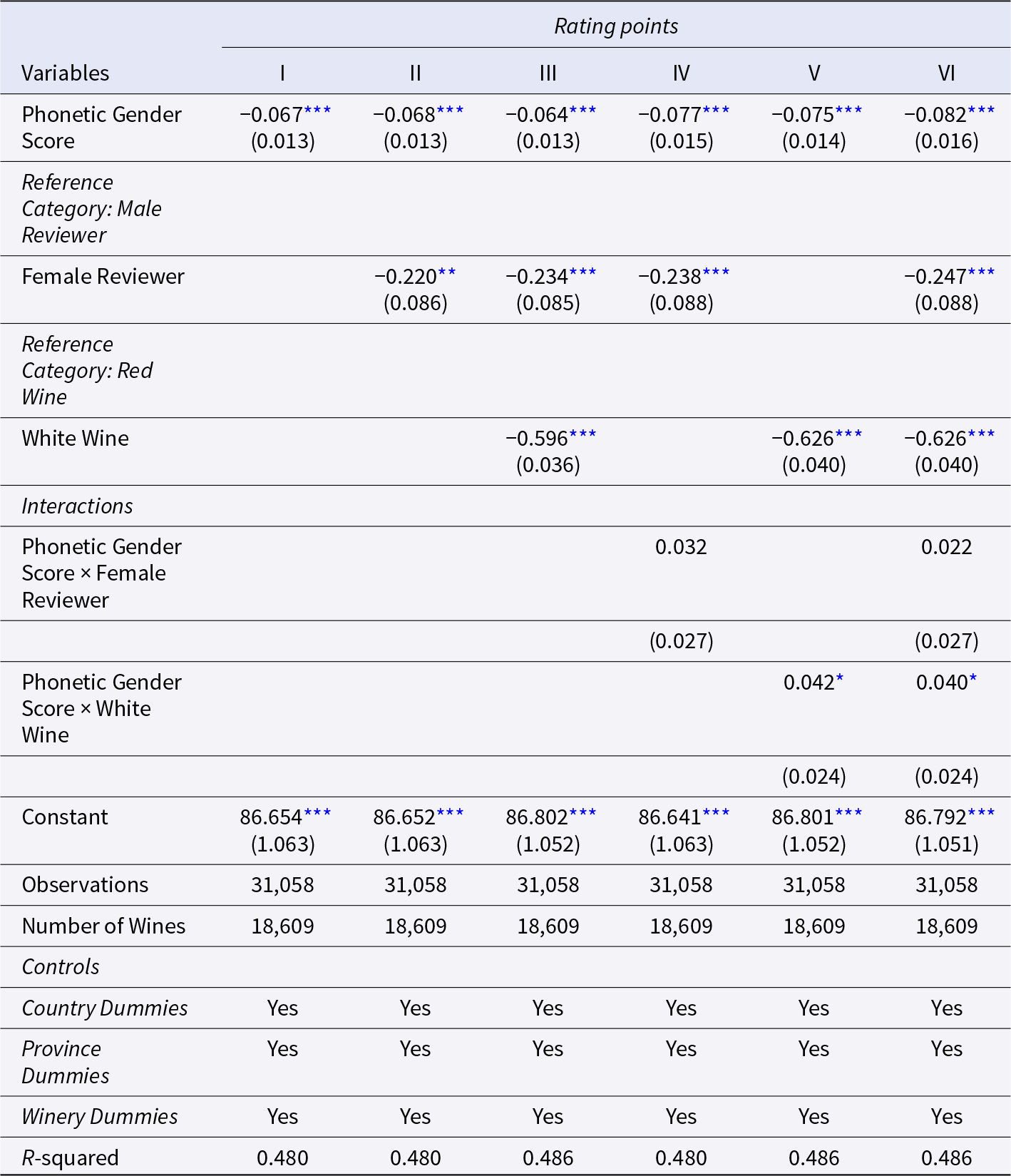

We consider six models to test our hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 empirically. First, we examine the impact of phonetic gender score on the respective wine rating (Model I), also considering the respective gender of the reviewer (Model II), before explicitly including the wine type, divided into red and white wine (Model III) in the estimation. In the following estimation (Model IV), we introduce the interaction term of phonetic gender score and female reviewer to test for the collective impact on rating points. Similarly, this approach is used in Model V by including the interaction term of phonetic gender score and white wine with the reference category red wine into the model to capture the relationship of phonetic gender score and wine category, controlling for product quality. Finally, Model VI is conducted as a robustness check to confirm the validity, robustness, and significance of the previously estimated Models I–V. Using 31,058 observations and 18,609 different wines, we control in all models for wine quality by using country, province, and winery dummy fixed effects representing wine characteristics and winery reputation for separating the effects of phonetic gender scores on rating points (see Table 5).

Table 5. Regression results

Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Models I–VI reveal that the phonetic gender score significantly negatively impacts the average rating points. Model I demonstrates that a one-unit increase in the phonetic gender score decreases the average rating by –0.067 points. Accordingly, a one standard deviation increase in the phonetic gender score reduces the overall rating by –0.089 standard deviations. The results in Model VI indicate that increasing the phonetic gender score by one unit decreases the rating by −0.082 points on average, with a significance level of 1%. The effects remain stable across all estimated models. In conclusion, these results suggest that a higher femininity score in names appears to have a highly significant negative impact. In comparison, a higher masculinity score in names appears to have a highly significant positive impact on professional evaluations.

At the same time, Models II, III, IV, and VI expose that female reviewers score lower on average than their male counterparts. We control these models for wine quality and follow a stepwise approach by first including the phonetic gender score and reviewer’s gender (Model II), adding the wine category (Model III) before interaction terms are included (Models IV and VI). Model VI shows the most significant effect while female reviewers score on average −0.247 points lower than male reviewers. The results are highly significant across the models at the 1% significance level and remain robust across all estimated models. We include the wine category in Model III. We control for phonetic gender score, reviewer gender, and product quality, resulting in the wine category white wine receiving, on average −0.596 rating points less than red wines.

To test for a possible feminine name advantage of wine varieties based on the reviewer’s gender and wine color, we capture the relationship between female reviewers and the wine category with gender score and introduce interaction terms. We find evidence that suggests that some degree of interaction is essential in explaining variations in the ratings made by professional critics, especially between a feminine variety name and white wines. The interaction of phonetic gender score and white wine shows that an increase in phonetic gender score by one unit increases the rating by 0.042 points compared to the reference category of red wine. This result remains stable in Model VI. Heterogeneity analysis will reveal that this effect is driven by male reviewers, while feminine-sounding white wines are penalized by female reviewers.

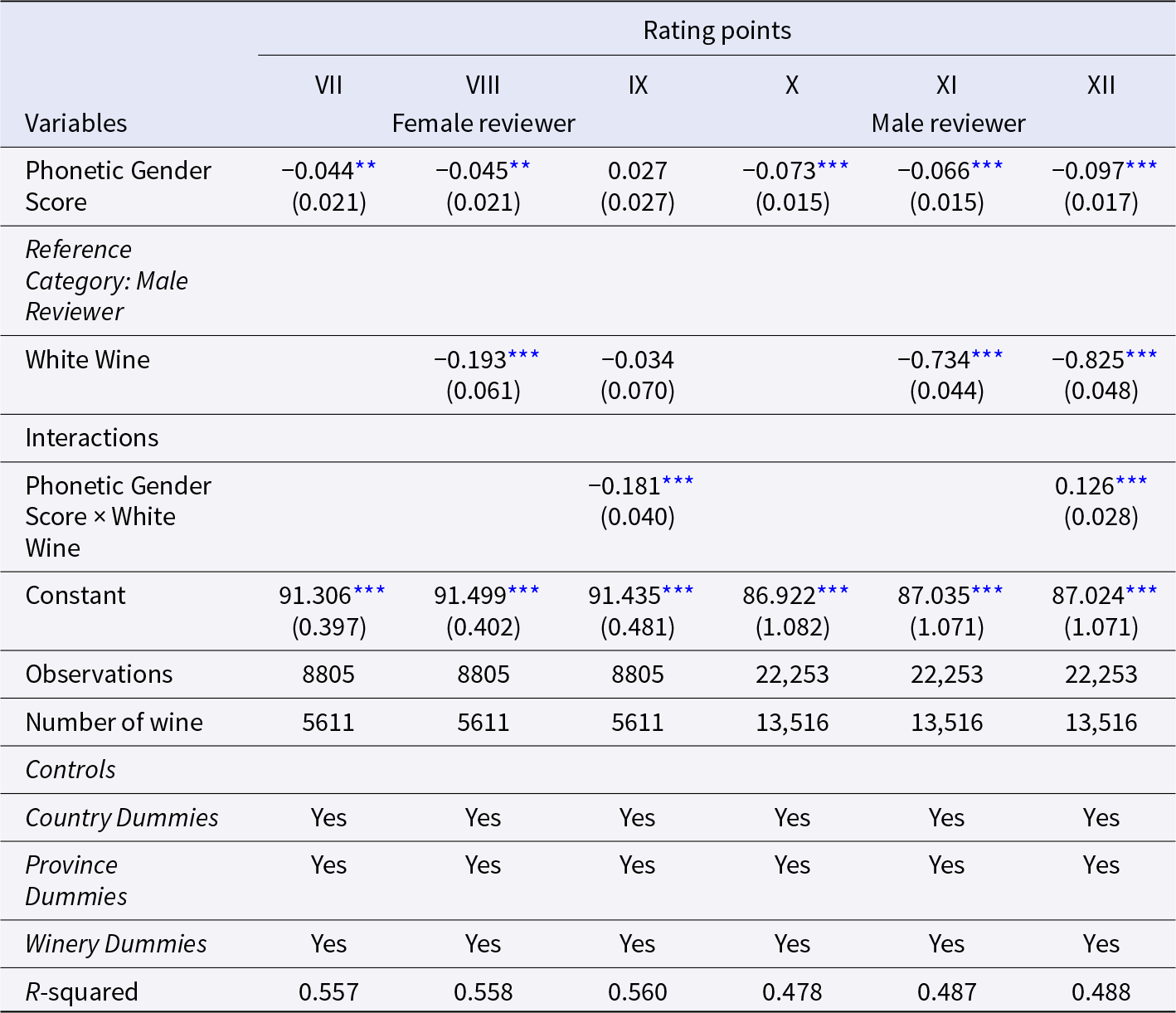

Model IV shows that an increase of gender score by one unit increases the rating points given by female reviewers by about 0.032 points, respectively 0.022 points in Model VI in contrast to male reviewers. However, the results are statistically insignificant. Therefore, we estimate separate regressions for men and women to analyze heterogeneity better. By isolating the effects, we are able to test whether the effects differ significantly by gender and to test the identity hypothesis more effectively (see Table 6).

Table 6. Separate regressions for female and male reviewers

Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05.

Including the interaction between phonetic gender score and white wine absorbs a large part of the effect of phonetic gender score, showing that female reviewers penalize feminine-sounding wines only when they are white. Instead, male reviewers penalize feminine-sounding wines only when they are red (the sum of −0.097 and 0.126 gives approximately 0 for white wines).

Heterogeneity analysis shows that this effect is driven by white wines for female reviewers and by red wines for male reviewers. The interpretation of these effects requires further investigation. One possible explanation is that each gender penalizes the femininity of the wine they know best—provided that female reviewers know better white wines and male reviewers know better red wines.

V. Discussion of results

Previous literature has examined names, linguistic properties, and product qualities imparted by inherent phonetic structures (e.g., Pogacar et al., Reference Pogacar, Plant, Rosulek and Kouril2015). In this context, the concepts of phonetic symbolism (e.g., Sapir, Reference Sapir1929), which ascribes specific (product) properties to phonetic patterns, and of names associated with gender and preferences are phenomena that have been investigated in mainly experimental studies so far (e.g., Klink, Reference Klink2000, Reference Klink2001, Reference Klink2009). Names are one of the first features consumers see or hear and are able to transmit information, meaning, trust, and reputation (Aaker and Keller, Reference Aaker and Keller1990).

However, little is known about how intrinsic product variety and phonetic gender effects affect professional evaluations, rankings, and ratings. These professional ratings are often determined by blind tastings to guarantee unbiased evaluations, where professional tasters are only provided with some information, such as the grape variety of the wine (e.g., Wang and Prešern, Reference Wang and Prešern2018). Particularly in the wine industry, wine tastings and professional ratings serve as trustworthy quality signals that consumers and prospects rely on (e.g., Storchmann, Reference Storchmann2012). To educate themselves, novice or infrequent wine drinkers may rely on professional rating scores (Yang et al., Reference Yang, McCluskey and Ross2009).

Wine differs depending on several factors. Some properties, like color or grading, are simple and affordable to measure. Others, like sensory or taste attributes, are challenging to quantify before consumption. The qualitative attributes of a wine are supposedly summed up by expert opinions (see Cardebat et al., Reference Cardebat, Figuet and Paroissien2014). Thus, the degree to which a person appreciates a wine depends on their expectation of quality, which is determined by a well-known label, the grape variety, or a wine critic’s ratings (Postman, Reference Postman2010). According to Friberg and Grönqvist (Reference Friberg and Grönqvist2012), a favorable review can result in a 6% rise in demand the week after publication. Kaimann et al. (Reference Kaimann, Spiess Bru and Frick2023) find that prices and product ratings are significantly related and that review consistency evolves and even determines current evaluations. Combris et al. (Reference Combris, Lecocq and Visser1997) state that objective cues (such as vintage and expert rating scores) significantly impact wine prices. However, sensory variables like tannin content and other quantifiable chemicals have not.

Therefore, ratings and tastings may show some limitations. The distinction between two wines may be so marginal that not even the most seasoned reviewer and taster could tell them apart (Barberà et al., Reference Barberà, Bossert and Moreno-Ternero2023). A similar scenario may occur when the wines are compared to a third wine. Postman (Reference Postman2010) spotlights that the results might be skewed simply by the wines’ presentational sequence. The personality of wine number four may easily moderate one’s enjoyment of wine number five. Wines also alter in the glass. For starters, even if the temperature was ideal when they were poured initially, it will quickly warm up to room temperature. Sensory adaptation, the process by which the strength of incoming stimuli is lowered with exposure over time, may mute other facets of the wine’s flavor. As a result, the wine that is tasted last will taste very differently from the wine that was tasted first. The results’ repeatability is another problem with blind tasting. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2008) found that the judges could not duplicate their results when served the exact wine numerous times.

Despite these limitations, we are confident to shed light on how gendered language, specifically masculine or feminine names, affects perceptions and evaluations. On average, products indicating masculine gender-scored names tend to be better rated compared to feminine gender-scored names. Since genders may be drawn differently to masculine or feminine names, we have presumed that the taster’s gender is another factor that needs further analysis to understand what influences tastings and ratings. Spielmann et al. (Reference Spielmann, Dobscha and Lowrey2021) show how different brand associations lead men and women to focus on gendered representations differently. In particular, men experience a brand relationship with brands that contain masculine representations, even for neutral products such as champagne, board games, or potato chips. Women do not relate to gendered brands differently from men. In our study, female reviewers give lower evaluations than their male counterparts, indicating gender differences in review behavior. Our results imply that products with feminine name scores are likelier to be rated lower by both women and men. This effect especially occurs for white wines for female tasters and for red wines for male tasters. These results emphasize the significance of considering gender bias when tasting and rating wines, and they point to the necessity to clarify the relationship between gender behavior and wine preferences.

VI. Conclusion

This study examines the relationship between gender characteristics and the linguistic cues of wine varietal names, and how this affects the quality judgments of experts who evaluate and rate wines. We find a significant phonetic gender difference in wine ratings, indicating that feminine names receive lower ratings than masculine names. A phonological gender difference is revealed by heterogeneity analysis based on reviewer gender, with female reviewers giving lower ratings for white wines and male reviewers giving lower ratings for red wines. This implies that the type of wine that people are more likely to recognize or enjoy—red for men and white for women—has a phonological penalty that is applied by both genders. We also observe that, on average, women rate wines lower than men.

As a result, the study reveals a gender bias in blind tasting evaluations and provides insightful information for wine critics, enthusiasts, and producers, as well as useful advice for industry participants. It helps companies negotiate consumer preferences and improve wine quality and reputation by providing insight into the unconscious processes of wine tasting. The study promotes a more sophisticated and informed conversation about wine evaluation by encouraging a reevaluation of the variables that influence expert judgments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editors, Karl Storchmann and Marica Valente, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and valuable feedback. This work was partially supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Collaborative Research Centre 901 “On-The-Fly Computing” under the project number 160364472-SFB901.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.