No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

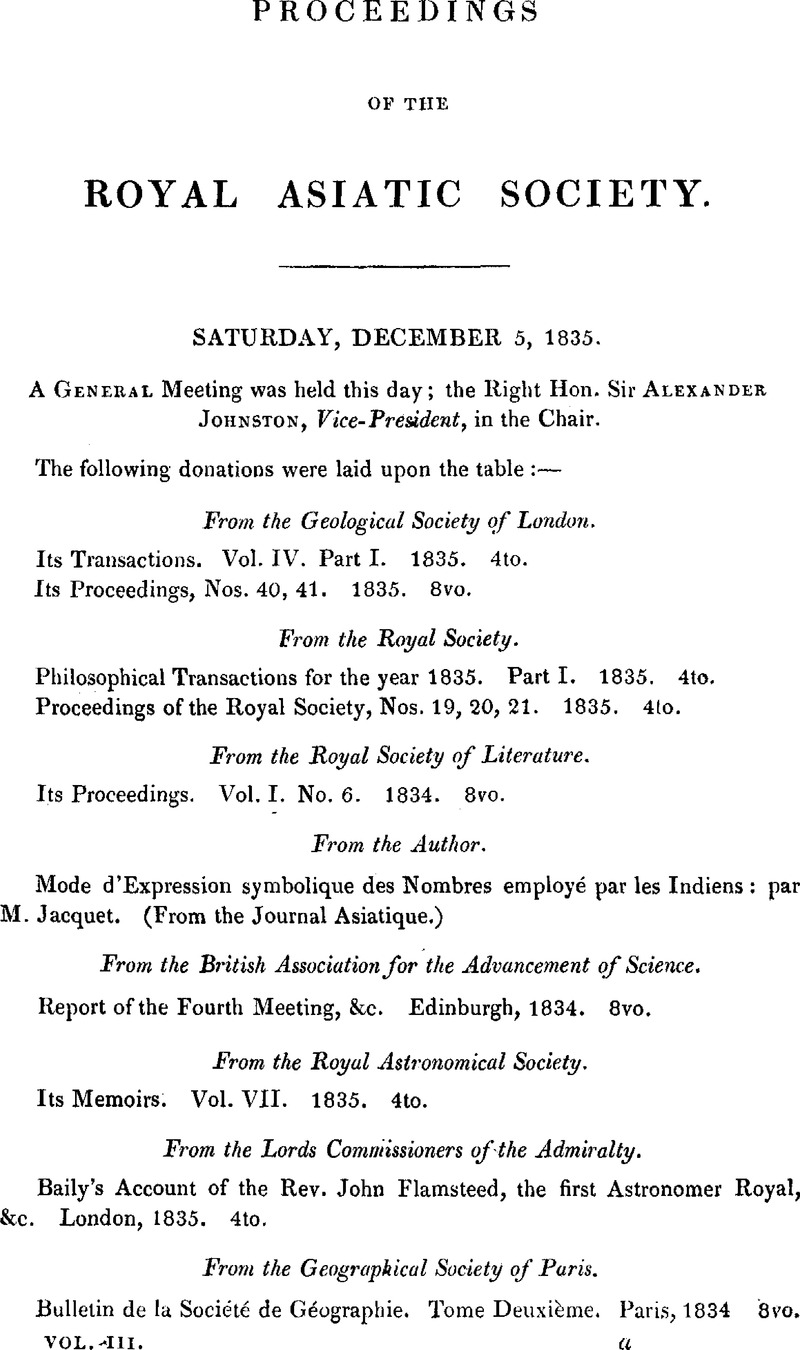

Proceedings of the Royal Asiatic Society

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2011

Abstract

- Type

- APPENDIX

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Royal Asiatic Society 1836

References

page iv note 1 Printed in the present Volume of the Journal.

* Pâli, or high Prákrit, a Bháshá merely, though a refined one, and easier than Sanskrit. Strongly as the spirit of proselytism possessed the earlier Buddhists, nothing can be more natural than the supposition that they employed that Bháshá to spread their doctrines: nothing, to my mind, more forced than the supposition that the eminently learned founders of Buddhism enshrined their refined and abstruse system in works composed in the Bháshá of a single province of India, when they had the powerful and universal Sanskrit at command.

* Published in the present Volume of the Society's Journal.

page viii note 1 This paper is printed in the present Number of the Journal.

* Mukhzun-ul-Udwiyeh, Toohfut-ul-Múmineen, Ikhtiáráti Budia, and the Taleef Shereef. The last has been translated by Mr. Playfair, Superintending Surgeon, Bengal Service.

* Colonel Sykes has been informed that 6484 cwt. were imported in 1834.

* It may be noticed as singular, that on the day (the 19th March) this paper was read to the Society, the following notice was given in the Athenœum, in the review of Balbi's “Literary Statistics of Austria:” — In the year 1819, the present emperor projected the technological museum, which is now one of the most interesting objects in Vienna. This collection, of all the products of industry, arrayed according to the provinces, their successive stages of manufacture, and their several improvements during the last sixteen years, is justly regarded as one of the most useful institutions of modern times. It is divided into three great classes — natural productions, manufactured articles, and models.”—Athenœeum, 1836, No. 208. The recent determination of the government to form, in this country, a museum, to be attached to the Board of Works, as applicable to the arts, of soils, rocks, and minerals, with models of mines, and the machinery attached to it, are strong confirmations of the utility of such institutions being generally recognised.

* Indica, Flora, vol. iii. p. 187.Google Scholar

* Owing to the kindness of Professor Wheatstone, of King's College, I am enabled to refer to M. Biot's investigations in vegetable physiology, which display, in a striking point of view, the practical bearing of the most abstract scientific investigations. M. Biot, in his experiments on the refraction of a ray of polarised light in vegetable solutions of different densities, discovered that the beet-root yields from eleven to fourteen parts in one hundred of the same kind of sugar as the sugarcane, and the parsnip fourteen parts in one hundred. “The great quantity of sugar obtainable from the latter root, gives M. Biot occasion to suggest, that as the manufacture of beet-root sugar can only be carried on profitably during a few months after the crop; and as the root is required to be gathered in the sowing season, when agricultural labour is expensive, and horses, &c. difficult to be obtained, sugar might be manufactured from the parsnip in the seasons of inactivity. And the author concludes his memoir, published in the Annales de Chimie, for Jan. 1833, in the following words: ‘Ces applications sembleront, peut-être, des consequences assez inattendues des expériences qui les ont fait naître; mais toute détermination positive des sciences est susceptible de progres et d'utilité, fut ce éloignée. Une observation microscopique, une propriété d'optique, qui ne semble d'abord que curieuse et abstraite, peut devenir plus tard importante pour nos intérêts agricoles et manufacturiers.’”

* Dr. Roxburgh's works have had less influence than they would have had, had they not been scattered through various publications not easily accessible; while his most popular work, the “Flora Indica,” remained in MS. for twenty years, and was only published in 1832. It is interesting to find him stating the following facts, in a letter dated, Samulcotta, 25th August, 1788: “Since the end of 1781, I have been stationed here; and as soon as I became acquainted with the seasons, soil, and produce of the country hereabout, I formed an idea that pepper and coffee would thrive as well in this Circar as in any part of Asia. My natural turn for Botany, Agriculture, and Meteorological observations, enabled me to form the idea upon, pretty certain grounds.” And, in another letter, we find him, on discovering the pepper in this very country, congratulating himself to a friend: “Now judge to yourself how right Doctor Russel and I have been, in conjecturing that the climate, &c. of the Circars would be favourable for the culture of black pepper.”—Oriental Repertory, vol. i. pp. 3 and 13.Google Scholar

* Bengal Husbandry, p. 155.

† Since this paper was read, I have been informed by Mr. Harpur Spry, F.G.S. of the Bengal Medical Service, that the opium cultivation has been extended to the Cawnpore district; and the opium produced there “has been reported by the person appointed to test the drug, as the best quality of all that is received at Benares.” “The cultivation was attempted a few years since, and proved a failure; but owing to the exertions and good management of Mr. Reade, the deputy collector, the Indian government is said to have derived a net profit, in the first year (1833), of 50,000 rupees; the second year, 75,000 rupees; and last year, the quantity was expected to be 200 maunds; and it will go on gradually increasing.”— (Private Letter to Mr. Spry.) At Saharunpore, still further to the north-west, I myself made some opium in 1829, which was submitted by Mr. Mackenzie, then Territorial Secretary, to the Medical Board, of which one specimen was pronounced, “perhaps equal, but certainly not superior to,” and others, “resembling in almost every particular,” some of an improved quality made by Capt. Jeremie the previous season in Behar, which the Medical Board, however, had “no hesitation in considering equal, if not superior, to the finest Turkey that comes into the market at home.” It was on these grounds, and from the superior quality of the opium cultivated in the Himalayas, that I, two years since, published the opinion, that “if it were an object to make the best opium for the European market, there is no doubt, that Malwa, and the north-western provinces, would be best suited for the experiment.”

* See Papers on Culture, &c. of Sugar in British India, App. iii. p. 4; also in Tennant's Indian Recreations, vol. ii. p. 41, quoted, “Bockford in his Indian Recreations,” by Baron Humboldt, in Political History of New Spain.