1. Introduction

This is a study of how existential constructions function in the expression of what corresponds to English somebody and nobody. Thai in (1) illustrates this: khraj0 baaŋ0 khon0 is, at least in (1a), the closest we get to English somebody. In (1b) we get khraj0, which together with the negator maj2 corresponds to nobody. But in both we also see an existential syntactic marker mii0.

Of course, neither khraj0 baaŋ0 khon0 nor khraj0 are exact counterparts of English somebody or nobody. The latter are indefinite pronouns. The Thai phrases are not quite the same, but they contain a pronoun too, viz. khraj0, which, depending on one’s analysis, is an interrogative pronoun or a pronoun with a meaning which allows both interrogative and indefinite uses, sometimes called ‘ignorative’ pronoun after Karcevski (Reference Karcevski and Godel1969). Example (2) illustrates the interrogative use.

That the sentences in (1) contain an existential marker too is not entirely surprising. We can see something similar in English in (3).

Languages may avoid an indefinite constituent early in the sentence, plausibly because of a ‘Given before New’ principle. This principle goes back to the Prague School of linguistics and perhaps before (Vachek Reference Vachek1966: 89) and achieved further prominence through e.g. Halliday (Reference Halliday1967: 205–211), Givón (Reference Givón1979a: 299), and Gundel (Reference Gundel, Hammond, Moravcsik and Wirth1988: 229). It says that there is a preference for given information to precede new information. With an existential construction the speaker explicitly marks that the ‘Given before New’ ordering is not adhered to and that what follows the existential, i.e. somebody or nobody or what corresponds to this in another language, is new information (see Givón Reference Givón1979a: 27; Van Alsenoy Reference van Alsenoy2014: 241). In some languages and in some constructions the pressure to mark that the given does not precede the new can be strong. Thus in Thai it is stronger than in English. To render somebody or nobody in Thai, at least when what renders ‘somebody’ or ‘nobody’ occurs before ‘see’, one has to use an existential marker. In this study we look in detail at the kinds of constructions shown in (1).

A few words on terminology. First, we will call somebody a ‘specific’ indefinite pronoun, nobody a ‘negative’ one and we will say that somebody and nobody express ‘specific’, respectively, ‘negative indefiniteness’. English also has anybody, which we call a ‘non-specific indefinite’ pronoun.

Negative indefiniteness is a subtype of non-specific indefiniteness. Hence it is no surprise that a language can express negative indefiniteness with a combination of a negator and a non-specific indefinite pronoun, as we see in English in (4c). In this paper we focus on specific and negative indefiniteness and leave non-specific indefiniteness aside. Second, we look at both ‘pronominal’ and ‘nominal’ indefinites. The latter are like pronominal ones, except that there is a noun or noun phrase that denotes the (non-)existing person. We see this in Thai in (5).

When it does not matter whether the indefiniteness is nominal or pronominal, we use the term ‘(pro)nominal’. Third, a construction that uses a syntactic existential marker to express either specific or negative indefinites is called an ‘existential indefinite construction’. A construction can be both (pro)nominal and existential. Thai in (1a), for instance, is pronominal and existential. Fourth, as adumbrated already, a (pro)noun that has one meaning (semantics), but both interrogative and indefinite uses (pragmatics), has been called ‘ignorative’ and we follow this practice. Finally, we use the terms ‘preverbal’ and ‘postverbal’ to refer to the position of the indefinite construction relative to the lexical verb, e.g. hen 4 ‘see’ in (5). The existential marker may also be a verb, but that is not the verb that the terms ‘preverbal’ and ‘postverbal’ relate to.

In Section 2 we will evaluate where we stand with our understanding of existential indefinite constructions for the world at large. In Section 3 we zoom in on four mainland Southeast Asian (‘MSEA’) languages, viz. Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, and Khmer. There are four reasons for this focus. First, in each of these languages existential indefinite constructions are prominent. We can thus hope that the language-specific similarities and differences between these languages help the general typology of existential indefinite constructions. Second, Kaufman (Reference Kaufman, Adelaar and Pawley2009: 194) compares MSEA, as part of the larger Asian mainland, to conservative Austronesian languages and claims that what is special for the expression of indefiniteness in MSEA is the use of ‘wh-words’, different from conservative Austronesian languages, which favor existential constructions. Though we cannot compare Austronesian and MSEA languages, we can at least have a closer look at four MSEA languages and check whether existential indefinite constructions do indeed take second stage there. Third, the four languages are ‘big’ languages, which are in general well described, the data are more accessible than for ‘smaller’ languages, and for each of the four languages, (pro)nominal indefiniteness has already attracted scholarly attention.Footnote 2 Fourth, the MSEA languages ‘are well known for their seemingly high degree of convergence in many if not all aspects of their grammar’ (Enfield Reference Enfield2019: 236). This has led to the hypothesis that MSEA is a Sprachbund (see Enfield Reference Enfield2005; Comrie Reference Comrie2007; Dahl Reference Dahl2008; Vittrant & Watkins Reference Vittrant and Watkins2019; Peterson & Chevalier Reference Peterson and Chevalier2022). This further invites one to find out how much similarity there is with respect to existential indefinite constructions, which has not been done yet. Of course, Enfield (Reference Enfield2019: 1, 234–235; Reference Enfield2021: 10; see also Enfield & Comrie Reference Enfield, Comrie, Enfield and Comrie2015: 14) warns that the restriction to the four national languages will not disclose the variation found in MSEA as a whole. It will thus not allow us to establish whether any feature of MSEA existential indefinite constructions is criterial for the MSEA Sprachbund, nor will this synchronic account tell us anything about the diachrony of the convergence, possibly established due to long time contact.

2. Existential indefinite constructions in the world

2.1 Specific indefinites

Despite the fact that there is a continuously growing voluminous literature on indefiniteness, to find out how existential indefinite constructions fare in the world at large, WALS (World Atlas of Language Structures), in particular Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a),Footnote 3 is still the best guide, at least for specific indefinites.Footnote 4 Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) classifies the world’s languages into five types. This is shown and illustrated in Table 1. The examples are taken from Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a).

Table 1 Languages classified as to the way they express ‘somebody’ and ‘something’.

i Pace Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) we would claim that somebody is a special pronoun too. Somebody obviously contains the noun body, that it is not a generic noun meaning ‘person’ or, as Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) has it, it is not a generic noun ‘anymore’. Thus English itself becomes mixed, as it has both the generic noun-based something and the special somebody.

ii The Spanish form alguien does not itself contain an interrogative element, but its Latin predecessor aliquem does.

The phrases ‘interrogative-based’ and ‘generic noun-based’ each cover two subtypes. Either the indefinite pronoun is identical to an interrogative pronoun or generic noun (like the German example wer) or it contains an interrogative pronoun or generic noun (like the English example something). The last column offers an approximation of the number of languages illustrating each type. That the number is approximate has several reasons. First, for the languages in which the indefinite pronoun is identical to an interrogative one, Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) admits that the view that such pronouns are not really interrogative, but only ignorative, could be correct. In that case the number for interrogative-based strategies will be lower, and we have to devise a new category, to wit, that of ignoratives, or perhaps consider the ignoratives to be a subtype of special indefinite pronouns. Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) does not make clear in how many of the 194 languages the interrogatives and the indefinites are identical, but the number must be significant. In a 100-language sample in Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997: 174), 64 languages are classified as ‘interrogative-based’ and in 31 languages the interrogatives and the indefinites are identical. The ignorative issue also affects the mixed category, of course, for languages could have non-ignorative and ignorative strategies. Note that the synchronic status of the ignorative is different from its etymology. According to Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997: 176, Reference Haspelmath2005a), historically ignoratives are always interrogative-based.Footnote 5

A second reason for calling the numbers for each strategy ‘approximations’ is that there may be more nominal strategies, translating somebody or something with the equivalent for person and thing, than a grammarian reports. This especially affects the number given for type B, but also the one for type D. Curiously, languages that use the numeral ‘one’ (as in English someone) or what used to be the numeral ‘one’, are also included in type A. One could argue that this is a separate type rather than a subtype.

Table 1 shows that it is rare for a language not to have a specific indefinite (pro)noun and to rely solely on an existential construction. Table 1 only has two languages, out of a total of 326. These languages are Mocoví (Guacuruan, Brasil) and Tagalog (Malayo-Polynesian, Philippines).

Tagalog in (6) has an existential marker may and there is no (pro)noun. It is interesting to compare Tagalog in (6) with Thai in (1a). In (1a), Thai also contains an existential marker, but there is a pronoun as well, viz. an ignorative one. Since Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) counts ignoratives as interrogatives, he classifies Thai as a type A language. But does the presence of the pronoun make (1a) any less existential? A terminological decision is needed, depending on whether one allows the term ‘existential’ for constructions that contain an existential marker independently of whether there is an exponence of the individual that exists. We have implicitly already chosen for the wider definition. Most importantly, the decision should ideally be the same when we come to negative indefiniteness, which has been investigated better than specific indefiniteness and also by other linguists. In this area the terminological decision is also the wider one, not only in Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b), but also in the earlier Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997) as well as in Kahrel (Reference Kahrel1996) and the later Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014). This gives additional support for the choice of the wider definition for specific indefiniteness. This then means that Thai should fall into category D, the mixed one. It has both an existential and an ignorative pronoun (interrogative-based for Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath2005a). In fact, as already illustrated with (5), Thai also allows the generic noun-based strategy – so it is mixed for an additional reason.

2.2 Negative indefinites

For negative indefiniteness we turn to Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b). The focus of this study is on whether an expression that ‘directly translates’ nobody or nothing occurs with a clausal negator or not. In standard English in (7a) there is no clausal negator, in substandard Engllish in (7b) there can be one.

Like for specific indefinites, the indefinite may be pronominal or nominal. This is also the wide sense that we adopt. Haspelmath’s definition is even wider, since ‘negative indefinite’ also includes ‘non-specific indefinites’, such as anybody, to which we object (see also van der Auwera & Van Alsenoy Reference van der Auwera and Van Alsenoy2016, Reference van der Auwera, Van Alsenoy, Turner and Horn2018). Table 2 shows Haspelmath’s findings: the definition of ‘negative (pro)noun’ in this table is his, not ours.

Table 2 Languages classified as to the way they express ‘nobody’ and ‘nothing’.

i There is only one language that is classified by WALS as requiring an existential construction for both specific and negative indefiniteness, viz. Mocoví, but there are no convincing data in WALS, and at least in the variety of Mocoví studied by Carrió (Reference Carrió2015, Reference Carrió2019), negative indefinites do not require an existential construction (Cintia Carrió, pers. comm.).

A language can be mixed, Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b) points out, and in more than one way. The parameter that has received most attention concerns the position of the negative indefinite relative to the verb, as in Italian in (8).

In (8a) the negative indefinite follows the verb and the clausal negator is obligatory. In (8b) the negative indefinite precedes the verb and the clausal negator is unacceptable.Footnote 6

Despite the fact that parameters for the typologies of specific and negative indefinites are different, both typologies contain an existential type. Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b) uses Nêlêmwa (Oceanic, New Caledonia) to illustrate a language that requires an existential construction for negative indefiniteness.

Note that (9) does not only have an existence marker, but also an exponent of the non-existent individual, viz. agu ‘person’. We thus see that ‘existential’ is defined more liberally than in Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a): for negative indefinite constructions an existential strategy may have a (pro)nominal exponent for the non-existent person. Thus Nêlêmwa in (9) is similar to Thai in (1b). Yet, for negative indefiniteness Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b) categorizes Thai as a non-existential type A language, presumably because the negative indefinite pronoun khray occurs with a verb (mii 0) which has to occur with a clausal negator. Our criticism is that the verb mii 0 is crucially an existential verb. This would ceteris paribus put Thai together with Nêlêmwa, but the matter is more complicated. When the Thai negative pronoun follows the verb, one does not use an existential construction.

The placement of the indefinite relative to the verb is the main parameter for classifying a language as mixed. But ‘mixed’ in Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b) does not allow for one of the strategies to be existential; we propose that ‘mixed’ should allow this. This is also where Tagalog should be classified, pace Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b), who categorizes Tagalog among the 170 languages that use a negative (pro)noun with a clausal negator.

But, as already mentioned in his earlier work (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997: 54), Tagalog has an existential indefiniteness strategy too.

Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014: 240) suggests that in Tagalog the choice is determined by whether or not the indefinite is the subject. This hypothesis does not contradict Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b), for he accepts that there is more than one parameter that determines the choice between various strategies. Furthermore, the two parameters, i.e. word order and subjecthood, may be related, at least for Thai. Thai is an SVO language, so the preverbal position is, ceteris paribus, also a subject position.

There may be more parameters. In a publication later than Haspelmath’s source (Bril Reference Bril, Hovdhaugen and Mosel1999), Bril (Reference Bril2002) suggests that in Nêlêmwa emphasis could play a role.

This way Nêlêmwa ceases to be a good example of a language that can only express negative indefiniteness existentially.

Though Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b) does not provide for a mixed category allowing existential constructions, his earlier work (1997) did. Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997: 214–215) claimed about SVO languages with non-specific pronouns that allow negative uses, that in some of these languages this pronoun cannot occur before the verb.Footnote 7 This is illustrated with Mandarin in (14).

To express the meaning of something like (14b), languages may resort to an existential construction. Mandarin serves to illustrate this.

So Mandarin also counts as a mixed language, pace Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005b), who classifies it as one of the 170 ‘unmixed’ ones.

When we compare the WALS accounts for specific and for negative indefinites, we learn that Haspelmath finds existential constructions for negative indefinites in 12 out of 206 languages, but for specific indefinites only in 2 out of 326 languages. Whereas the number of languages with specific indefinites is much bigger than that for negative indefinites, we thus find much fewer existential constructions for specific indefiniteness than for negative indefiniteness. This might be taken to suggest that the existential strategy is associated more with negative indefiniteness than with specific indefiniteness. The numbers, however, do not warrant this hypothesis. First, the accounts of specific and negative indefiniteness define ‘existential’ in a different way. The study of negative indefiniteness uses the wider definition allowing an exponent of the non-existent entity. So it is not surprising that the number of negative existential constructions is higher than that of specific indefinite constructions. The second reason is that the data sets of the two studies are not representative samples. So one cannot, in principle, compare the numbers.

So far we have focused on Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997, 2005b), but there are two more typological accounts. Both Kahrel (Reference Kahrel1996) and Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014) write about negative existential indefinite constructions, but their category of existential constructions is possibly wider than that of Haspelmath’s. They include the construction illustrated for Nadëb (Nadahup, Brasil) in (16), which Weir (Reference Weir, Kahrel and Van den Berg1993: 301) analyzes as an ‘ascriptive’ or ‘equative’ construction.

Interestingly, both Kahrel (Reference Kahrel1996) and Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014) acknowledge a mixed category allowing one of the strategies to be existential. In his sample of 40 languages, Kahrel (Reference Kahrel1996: 38) has seven languages with an existential negative construction, five of which are part of a mixed strategy. Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014: 238–239) has 179 languages, with 20 allowing existential negative indefinite constructions, possibly half of which are mixed. So existential negative indefinite constructions may occur at least as often as an alternative to a non-existential strategy than as the only option, and maybe the mixed strategies are more common.

A final point is that the ‘mixed’ label has by now covered different things. In the discussion of specific indefiniteness we focused on the presence of an existential marker and on the presence and the nature of the (pro)noun. Thai is mixed because the sentences contain both an existence marker and an exponent of the non-existent person and also because the latter can use either an ignorative or a generic noun – see (1) and (5). In the discussion of negative indefiniteness, however, the nature of the (pro)nominal exponent is irrelevant. What matters is the presence or absence of the clausal negator and the presence or absence of the existence marker. For the latter parameter Thai is mixed again, for (1b) contains the existence marker and (10) does not.

2.3 Conclusion

Our typological understanding of existential indefinite constructions is unsatisfactory. We still have to rely on the two WALS chapters. But this is problematic. For one thing, ‘existential indefinite construction’ is defined in a different way for specific versus negative indefinite constructions. Negative indefinite constructions may have a (pro)nominal exponent of indefinites in addition to the existential marker, but specific ones may not. In addition, the classification of mixed languages should allow for a mix between existential and non-existential strategies, both for specific and for negative indefinites.

It is true that we know more about negative existential constructions than about specific existential constructions, largely due to Haspelmath’s own pre-WALS work (1997) and to Kahrel (Reference Kahrel1996) and Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014), but our knowledge is deficient there too, for none of these works focuses on negative existential constructions. The general problem is also that descriptive grammars, the main source for typological works, generally fail to treat existential indefinite constructions in a satisfactory way. So we need supplementary, language-specific studies. This is what we will do in the second half of this paper.

3. Existential indefinite constructions in Mainland Southeast Asia

3.1 Introduction

Of the four MSEA languages of which we study the expression of indefiniteness, two were discussed in Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a, Reference Haspelmath2005b), viz. Thai and Vietnamese. These two languages have existential constructions, as already illustrated for Thai, but neither was recognized for this by Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a, Reference Haspelmath2005b): both languages were classified as making their indefinites with interrogatives. In what follows we will provide a more satisfying account and we add two more MSEA languages, viz. Lao, genealogically closely related to Thai, and genealogically unrelated Khmer.

This study has many limitations. The most important one was mentioned at the end of Section 1: it is obvious that a study of just four MSEA languages falls short of sketching the variation that is expected to emerge if either many more MSEA languages or a balanced sample of them would be studied. This study is thus very much an invitation to undertake more comprehensive work. Second, we only study human indefinites, i.e. constructions corresponding to English somebody and nobody. We leave for later the study of non-human constructions such as the ones corresponding to English something and nothing, but also somewhere and nowhere, sometimes and never, and a few more. Third, as in the previous section we only cover specific and negative indefiniteness, so not non-specific indefiniteness. Fourth, there is only one parameter of variation that will be studied, viz. whether or not the human specific or negative indefinite construction occurs before or after the verb. There might be other parameters of variation. Fifth, our account is based on a small number of grammatical descriptions and native speaker judgments. Regional, register or stylistic variation will fall under the radar. Also, when a meaning can be expressed by more than one strategy, one strategy might be much more frequent than the other strategy or strategies or have different discourse-grammatical functions. Only corpus work or a questionnaire survey would allow solid frequency statements and only Givón style discourse analysis (Givón Reference Givón1979b, Reference Givón1983) will uncover the finer discourse-structural dimensions of the various strategies. Sixth, we do not study emphatic strategies. We study the way the languages express ‘nobody’, for instance, but not ‘not even one person’ or ‘nobody at all’. The distinction between an emphatic and a non-emphatic strategy is not always clear, of course, primarily because an emphatic strategy may be in the process of bleaching and turning non-emphatic. We also steer clear of rhetorical expression types, such as the one illustrated for Khmer in (17).

The translation has ‘no one’, but John Haiman (pers. comm.) points out that (17) is literally a rhetorical question meaning ‘Who dared stand up to him?’, with ‘No one’ as the implicated answer. Seventh, we do not discuss the nature of what follows the existential indefinite construction or the relation between that part and the existential indefinite construction. Consider Thai in (1a) again. The existential indefinite construction is mii 0 khraj 0 baaŋ 0 khon 0 and the remaining part of the sentence is hen 4 chan 4. Both parts contain verbs, viz. mii 0‘exist’ and hen 4 ‘see’. Is the appearance of the two verbs in any way related to the phenomenon of ‘verb serialization’, prominently present in MSEA languages (see e.g. Bisang Reference Bisang1992)? Also, is hen 4 chan 4a kind of reduced relative clause, somewhat similar to what can be called a ‘relative infinitive’ in English (18a) (e.g. Breivik Reference Breivik1997), sometimes also called ‘modal’ (e.g. Šimik Reference Šimik2011), or the ‘contact clause’ relative in English (18b), after Jespersen (Reference Jespersen1933: 360)?

These are interesting issues, but they are well beyond the confines of the present study. Relatedly, MSEA languages may also have uncontroversial relative clauses, such as Thai in (19), and these will also be left out of account.

Furthermore, there has been much research on the negation of existence of states of affairs, prompted by Croft (Reference Croft1991) and strongly associated with the work of and inspired by Veselinova (most recently Veselinova & Hamari Reference Veselinova and Hamari2021). At least in some languages, the expression of the negation of physical entities and states of affairs may be related – see e.g. van der Auwera, Van Olmen & Vossen (forthcoming) on Tagalog. This issue will also be shelved for future research.

We will use the same terminology as in Section 2. We will thus have occasion to use the term ‘ignorative’ for each of the MSEA languages. The term has not been used in MSEA scholarship. The issue of how to deal with pronouns that have both interrogative and indefinite uses, however, has not been avoided there. For Lao, for example, Enfield (Reference Enfield2007: 86) is compatible with our account. He is aware of the term ‘ignorative’, through Wierzbicka (Reference Wierzbicka1980), but prefers to call ignoratives ‘indefinites’.Footnote 8 This seems to be a terminological difference only. When one claims that the meaning is always indefinite, one does not claim that the interrogative meaning is the same, only that it includes the indefinite meaning. In this account, ‘indefinite’ captures what is common between indefinite interrogative and indefinite non-interrogative meanings. ‘Ignorative’ covers the same common meaning. One also finds linguists giving pride of place to the interrogative meaning, as in Tran & Bruening (Reference Tran, Bruening, Hole and Löbel2013) for Vietnamese. In part motivated by Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997), they take the elements that we take as ignorative as basically or ‘underlyingly’ (Tran & Bruening Reference Tran, Bruening, Hole and Löbel2013: 218) interrogative – although Haspelmath’s claim (Reference Haspelmath1997: 176) concerned only the diachrony of ignoratives. The interrogative hypothesis is also found in Emeneau (Reference Emeneau1951: 59), for instance, again for Vietnamese, though Emeneau is aware of a possible Indo-European bias for wanting to distinguish between interrogative and indefinite pronouns. For Khmer we see Jacob (Reference Jacob1968: 122) implicitly embracing an interrogative hypothesis when she writes that ‘[m]any of the question words … may have different lexical meanings … They may be used to express indefiniteness, having in English the translation of “some” and “any”’. And for Thai Jenny (Reference Jenny, Vittrant and Watkins2019: 577) writes that interrogatives are ‘also used as indefinites’.

3.2 Thai

We have already used Thai to illustrate the general issues. Now we will try to give a more comprehensive description. First, when the indefinite is specific, Thai has five strategies. In each the existential marker is obligatory. When the specific indefinite is postverbal, the strategies are very similar, except that there is no existential marker.

As argued before, we take khraj0 to be an ignorative as it can also have an interrogative function. Without using the term ‘ignorative’, traditional accounts (e.g. Yates & Tryon Reference Yates and Tryon1970; Iwasaki & Ingkaphirom Reference Iwasaki and Ingkaphirom2005) are compatible with this analysis. Historically, khraj0 is both generic noun-based and interrogative-based, as it derives from khon0 and an interrogative determiner raj (Teekhachunhatean Reference Teekhachunhatean2003: 112; Jenny Reference Jenny, Vittrant and Watkins2019: 595, 608). Note that nɯŋ1 follows the classifier; it then ‘functions like an indefinite article’ (Jenny Reference Jenny, Vittrant and Watkins2019: 577) and we gloss it as ‘ind.sg’. When nɯŋ1 precedes the classifier, it is a numeral (‘one’).

For the negative indefinite, the preverbal position only has two options, both with the existential marker.

In postverbal position, there is only one option.Footnote 9

In (23) replacing the ignorative by the generic noun khon is possible, but the resulting sentence means that the speaker did not see humans, different from, e.g. birds or horses.

We can now go back to Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) and the claim that the specific indefinite constructions of Thai are interrogative-based or, in our recasting, that these constructions are ignorative. First, it is true that Thai has ignorative indefinite strategies, but there are generic noun strategies too and they are no less important. Of the 14 patterns illustrated in (20) to (23) for both specific and negative indefiniteness, six contain an ignorative and six contain a generic noun. If we count the patterns with only a classifier deriving from a generic noun as a generic noun pattern too, then we have eight generic noun-based patterns. Second, there are seven patterns with an existential marker. In line with what we remarked earlier, there is no indefinite pattern that uses an existential marker that is not accompanied by a (pro)nominal exponent of the non-existing entity. But that does not mean that the existential marker is unimportant. Table 3 shows in the top rows in what context we find the existential strategy.

Table 3 Strategies for human indefiniteness in Thai.

We see that the existential strategy is strongly associated with preverbal indefiniteness, for it is necessary there, and it is impossible for postverbal indefiniteness. It can combine with both an ignorative and a generic noun. Third, in the Haspelmath classification, ignoratives and generic nouns can either occur by themselves or they are marked for specificness, but there are no details on their nature or use. Thai shows that there is more than one type of specificness marking: there is a classifier phrase with baaŋ 0, but there is also a classifier phrase with nɯŋ 1, which we analyzed as marking singular indefiniteness, and they are incompatible. Other points of interest are that the singular indefiniteness phrase can occur without either an ignorative or a generic noun and that negative indefiniteness does not occur with specificness or indefiniteness marking.

In the preverbal existential context, ignoratives and generic nouns behave in a very similar way. This is true also for the postverbal non-existential contexts. When the sense is specific, they have to be marked for specificness or indefiniteness. There is one difference, i.e. when the sense is negative, we can get a bare ignorative, but not a bare generic noun. It is not clear whether this difference is significant. Perhaps this can be interpreted to mean that ignoratives are more strongly associated with negativity than generic nouns.

In the next section we will see to what extent Lao behaves in the same way.

3.3 Lao

Lao is closely related to Thai, but, to the extent that we can see, the patterns are a little different. Example (24) documents how Lao expresses preverbal specific indefiniteness. Note that phaj3 is the univerbation of phuø-daj3, which can always replace phaj3.

The main similarities with Thai are the following. First, in both languages we see existential markers, ignoratives, generic nouns, and both specific and indefinite classifier phrases. Second, in both languages existential markers are prominent. But then there are differences. First, the Lao existential marker is not necessary. Hospitalier (Reference Hospitalier1937: 180) does not even mention the existential strategy, but at least in present-day Lao existential strategies are more common. Second, the classifier strategies do not use khon 2 but phuø. Third, though nùng 1 can both precede and follow the classifier in both languages, the association with indefiniteness may be different. In Thai the different positions relate to the difference between an indefinite article (after the classifier) and numeral use (before the classifier). In Lao the counterpart allows these orderings too, but Enfield (Reference Enfield2007: 105) does not link this to different meanings. Nevertheless, for an existential construction like in (24) he glosses nùng 1 as ‘a/one’ and he makes clear that the main function is to mark singular number. We therefore gloss it as ‘ind.sg’, like we did for Thai. Fourth, whereas in Thai the specific and indefinite classifiers phrases are incompatible, (24h) shows that Lao allows them to co-occur. A fifth difference is that Lao has no counterpart to Thai khraj 0. Lao instead uses phuø-daj 3 or the shorter phaj 3. Phuø-daj 3 and phaj 3 are ignoratives, they also have an interrogative use, but these Lao words also show a universal quantifier use (‘everybody’), as in (25).

In (26) we see the options for specific postverbal indefinites.

According to Enfield (Reference Enfield2007: 88) a bare phaj3 is possible when the specific indefinite is postverbal, but our informants ruled the indefinite reading out or called it ‘unnatural’: its only reading is interrogative.

Again, there are similarities and differences with Thai. Differences concern the uses of the classifier phrases. The most important similarity is that the structure allows a bare generic, but not a bare ignorative.

For negative preverbal indefiniteness, Lao differs from Thai in an interesting way. Like Thai, Lao has an existential construction with either an ignorative or a generic noun, but there are also a few non-existential constructions that literally mean ‘Everyone didn’t see me’, with the universal quantifier scoping over the negation.

The universal strategies in (27c–f) are peculiar. An ‘all not’ strategy makes sense from a logical point of view: if a negative predicate holds true of all, then there is nobody of which the positive predicate holds true. In English, however, sentences like (28a, b) with the interpretation of (28c) are unusual.

Languages that use universal quantifiers as a dedicated negative indefiniteness strategy are rare. Neither Kahrel (Reference Kahrel1996) nor Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1997, 2005b) even provide for this type. In her 197-language sample Van Alsenoy (Reference van Alsenoy2014: 242–249) does, but she only finds it in four languages. We are confidentFootnote 11 that Lao, not included in the Van Alsenoy sample, is such a language too.

Negative postverbal indefiniteness is also a little different. In Thai the generic noun is not appropriate, but in Lao it is.

Table 4 gives a survey of the various strategies.

Table 4 Strategies for human indefiniteness in Lao.

To conclude, in Lao existential constructions are associated with preverbal indefiniteness, but the association is not as strong as in Thai, for both specific and negative indefiniteness can do without existential marking. Like in Thai, however, existential constructions are not used for postverbal indefiniteness. We can represent the similarity and the difference in the ‘accessibility’ hierarchy of Table 5.

Table 5 Existential constructions in Thai and Lao.

In both languages specific indefiniteness allows ignoratives and generic nouns, which tend to be accompanied by specificness or indefiniteness marking, with the exception of specific postverbal indefiniteness, which allows a bare generic (in both languages). The reason, we hypothesize, is that generic nouns do not ‘suffer’ from the indefinite – interrogative – vagueness. Lao has two more exceptions: both bare ignoratives and generic nouns are allowed for specific preverbal indefiniteness. Interestingly, in these uses ignoratives and generic nouns still require the existential marker. So the bareness of the noun does not mean that there is no other special marker. In particular, we take the existential marker to signal that the entity thus introduced is not ‘given’ (see the ‘Given before New’ hypothesis, introduced in Section 1). The accessibility hierarchies in Tables 6 and 7 show the similarities and the differences.

Table 6 ind or spec marking with ignorative constructions in Thai and Lao.

Table 7 ind or spec marking with generic noun constructions in Thai and Lao.

The main difference is that Lao allows an ‘all not’ strategy for negative preverbal indefiniteness.

3.4 Vietnamese

We now turn to Vietnamese. When we discussed Lao we interlaced the analysis with comparative remarks on Thai, because the languages are closely related. For genealogically unrelated Vietnamese – as well as for Khmer in Section 3.5 – we will save the comparison to the end of the section.

To express specific preverbal indefiniteness in Vietnamese one uses an ignorative or a generic noun. An existential marker is optional when the ignorative is followed by đó, but obligatory when the ignorative is not followed by đó or when the exponent is a generic noun. We gloss đó as a marker of specificness. In other contexts it has a distal demonstrative meaning (Nguyễn Đình-Hoà Reference Nguyễn1997: 133).

Một is used both as the numeral ‘one’ and as the indefinite article. From Do-Hurinville & Dao (Reference Do-Hurinville, Dao, Vittrant and Watkins2010: 401) it would appear that một in (30c) can be interpreted as an indefinite article. That ai is an ignorative is illustrated in (31), which shows an interrogative use.

Nào is an ignorative determiner: an interrogative use is illustrated in (32).

When the specific indefinite is postverbal, the existential marker is not used and we only see ignoratives in combination with the specific marker, with an optional indefinite marker.

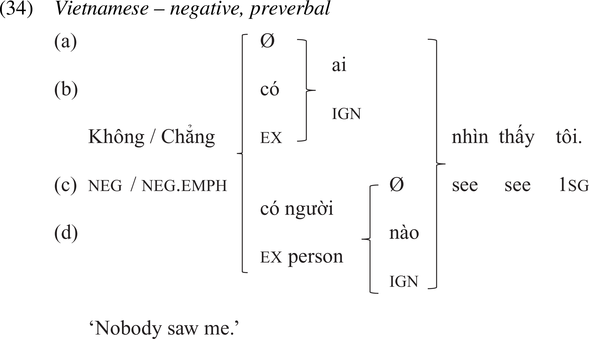

The strategies for negative preverbal indefinites are similar to the ones we see for specific preverbal indefinites. The biggest difference is that negative preverbal indefiniteness does not allow a specific or indefinite marker.

Note that một can be added here, as in (30) and (33), but in (34) it brings along emphasis (not a single) and so we do not include this use of một. Example (35) shows the strategies for negative postverbal indefinites. We only have ignorative constructions.

The various strategies are surveyed in Table 8. The combination of the generic noun người with the ignorative determiner nào counts as an ignorative construction.

Table 8 Strategies for human indefiniteness in Vietnamese.

Compared to Thai and Lao, the strongest similarity is that existential constructions are again restricted to preverbal indefiniteness (see Table 9). It is closest to Thai because existential constructions are necessary.

Table 9 Existential constructions in Vietnamese, Thai, and Lao.

In Vietnamese, generic nouns have a limited use: they are only used for preverbal specific indefiniteness, except that they are transparent components of the phrase người nào ‘person ign’, which we have analyzed in its entirety as an ignorative. We again see ind and spec marking, appearing only for specific indefiniteness, though this time not with a classifier construction. In Vietnamese specific and indefinite markers can occur together – see (30c, g) and (33b). In Lao this is possible too, but the markers occur with classifiers there.

3.5 Khmer

Finally, we turn to Khmer, first with specific preverbal indefiniteness.

Once again, we see existential markers, generic nouns, ignoratives, and indefinite classifier phrases, but no specific classifier phrases or markers. There are three different generic nouns that appear here: neak, mmuh, and kee:. Footnote 12 M-neak is analyzed as a ‘quantifier classifier’ construction by Haiman (Reference Haiman2011: 144) and m- is the short form of muaj ‘one’ (Haiman Reference Haiman2011: 74). The long form muaj neak is hardly ever used. Haiman (Reference Haiman2011: 74, 176–177) takes both the long and short form as numerals, yet we venture the hypothesis that the numeral sense in m-neak has changed to an indefinite singular sense and we use the ‘ind.sg’ gloss accordingly. M-neak is obligatory: without it (36a) would have an interrogative reading, and in (36b–d) the indefinite phrases would translate as ‘people’. We follow Haiman (Reference Haiman2011: 331, 341) in analyzing na: as an ‘indefinite/interrogative’ determiner, i.e. an ‘ignorative’ one, in our terminology. This makes the phrase neak na: ignorative too. Example (37) illustrates the interrogative use of na:.

Interestingly, Haiman (Reference Haiman2011) – but not Jacob (Reference Jacob1968) – mentions another ‘who’ phrase, viz. nau: na: (or nauna:). It contains yet a fourth human generic noun, viz. nau (Haiman Reference Haiman2011: 144, 176). Nau na: is ignorative, having both interrogative and indefinite uses, but it is not used for preverbal specific indefiniteness.

Nau na: is fine, however, for postverbal specific indefiniteness.

Example (40) shows the strategies for negative preverbal indefiniteness.

Table 10 gives an overview of the various strategies.

Table 10 Strategies for human indefiniteness in Khmer.

Table 11 compares Khmer to the other languages. For existential constructions, Khmer is similar, but not quite the same. We will come back to this difference in Section 4. Different from the other three languages, Khmer has no specificness marking. Indefiniteness marking seems to be necessary in all uses, which also means that bare ignoratives and generic nouns are not possible. In these respects, Khmer is the divergent language, yet for the use of existential constructions, Table 4 shows it to be in between Vietnamese and Thai, on the one hand, and Lao, on the other hand.

Table 11 Existential constructions in Vietnamese, Thai, Khmer, and Lao.

4. A conclusion and a conjecture

How does the typological study of existential indefinite constructions profit from the study of these constructions in four MSEA languages? First, we pointed out that both Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a,Reference Haspelmathb) and Kaufman (Reference Kaufman, Adelaar and Pawley2009) minimize the role of existential constructions for the expression on indefiniteness in Thai and Vietnamese (Haspelmath) or in the South Asian area (Kaufman). This is unwarranted, at least to the extent we can see from Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, and Khmer. A robust finding for these languages is that existential constructions are typical for the expression of preverbal indefiniteness – see Table 11. Second, this does not mean that there are no non-existential markers that may combine or alternate with existential markers. As pointed out by Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a), indefiniteness also relies on ignorative constructions and generic nouns. They may occur without existence markers, but they may also combine with them, thus militating against the typology of Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a) in which existential markers and ignoratives or generic nouns exclude each other. Third, another parameter, not focused on in Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a), is the use of dedicated specificness and indefiniteness markers. A language may have both or only one, and when the language has both, they may or may not be interchangeable and they may or may not combine with each other.

There are strong similarities between the expression of indefinite constructions in the four languages, most strongly so with respect to our main issue, that of existential indefinite constructions. There are three ways in which existential indefiniteness is dedicated to the preverbal position: existential indefinite constructions are either necessary or possible for the preverbal position or they are necessary for negative indefiniteness and possible for specific indefiniteness, but in each case they are impossible for the postverbal position.

We end on an explanatory conjecture on the hierarchy shown in Table 11. What all four languages show is that preverbal indefiniteness is most accessible for existential constructions, but what the Khmer data show is that at least in this language negative preverbal indefiniteness is more accessible than specific preverbal indefiniteness. We pointed out in Section 2.2 that a superficial reading of the numbers of Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath2005a,Reference Haspelmathb) – with 12 on 206 ‘existential’ languages for negative indefiniteness versus only two on 326 ‘existential languages’ for specific indefiniteness – would also support this conclusion. We resisted this conclusion then for two reasons (‘existential’ is not defined in the same way for specific and negative indefiniteness; the datasets of 206 and 326 languages are not representative samples). Yet that does not preclude that the difference in accessibility for specific and negative indefiniteness has a higher crosslinguistic validity. By itself, the data on Khmer, i.e. just one language, cannot be conclusive either. But recent work on Malayo-Polynesian languages brings more backing. Van der Auwera et al. (forthcoming) asked four speakers of Standard Malay, three of which also helped for colloquial peninsular varieties, and also one speaker for Standard Indonesian, Sundanese, Balinese, Banjar, and Kulikusu, what their most natural translations of the sentences in (42) would be.

It is important to emphasize that speakers were not asked to provide all the possible translations in their languages, only what they would prefer, which is different from the research reported on in this paper. Still, naturalness tells us something about accessibility too. The results are the following: for (42a) all of the 12 speakers used an existential construction, like the one in (43a). For (42b) eight translations had an existential construction, but four did not – see (43b, c).

We conclude that for some languages negative preverbal indefiniteness is more in need of existential constructions than specific preverbal indefiniteness. Why should this be so?

In Section 1, we subscribed to Givón’s (Reference Givón1979a: 27) and Van Alsenoy’s (Reference van Alsenoy2014: 241) hypothesis that the preference of existential constructions for preverbal indefiniteness is explained by the ‘Given before New’ principle. A preverbal indefinite is an early ‘Non-Given’ and the existential marker flags this construction as ‘Non-Given’. What we see in specific preverbal indefiniteness is the ‘Non-Given’ that we are used to, viz. the ‘New’, and this ‘New’ entity can then become ‘Given’ in the ensuing discourse. With negative preverbal indefiniteness the ‘Non-Given’ entity, however, is not a ‘New’ one. It is in fact an entity that does not exist, a ‘non-entity’, which has little or no potential of becoming ‘Given’ in the later discourse.Footnote 13 Put in a different terminology, different from a specific preverbal indefinite construction, the negative one cannot have a ‘presentational’/‘presentative’ function; it has a ‘terminative’ one (McGregor Reference McGregor2010: 213). We propose, therefore, that there is a ‘Given before Non-Given’ principle, either as an alternative to the traditional ‘Given before New’ principle or as a more general principle. With respect to a ‘Given before Non-Given’ principle, introducing something that does not even exist is a more radical breach of the principle than merely introducing something new. As an afterthought, the last quarter of the century has seen much effort on providing a more refined understanding of types of ‘Givenness’, with either conceiving it as a gradient notion or as distinguishing subtypes, with e.g. the ‘Given’ that is explicit in the discourse versus only inferable, accessible, or activated (e.g. Gundel, Hedberg & Zacharski Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993; Hansen & Visconti Reference Hansen, Visconti, Rossari, Ricci and Spiridon2009). The proposal to rethink the ‘New’ pole as ‘Non-Given’, allowing for the subtypes of ‘Non-Existent’ and ‘New’, is an attempt to refine the ‘Given before New’ principle from the other end.