IntroductionFootnote 1

During the last decade, the universal basic income (UBI)Footnote 2 has gained massive prominence. Current concepts usually construct the UBI as providing all people with regularly paid unconditional minimum income, without any means test or work requirements, ensuring their subsistence is independent of paid labour. Despite many differences with regard to the actual design of a UBI (eg concerning questions such as who should be eligible for UBI, how should children be included, what should the exact amount of the UBI be, or – probably most fiercely debated – how should the money for the UBI be generated), it has been argued that all UBI approaches that share the key principles of unconditionality, universality, individuality and sustainability relate to a unique concept of social justice: the idea of combining equality and freedom as ultimate goals (van Parijs, Reference Parijs1997). As we will outline in greater detail below, this distinguishes the UBI from other concepts of social justice.

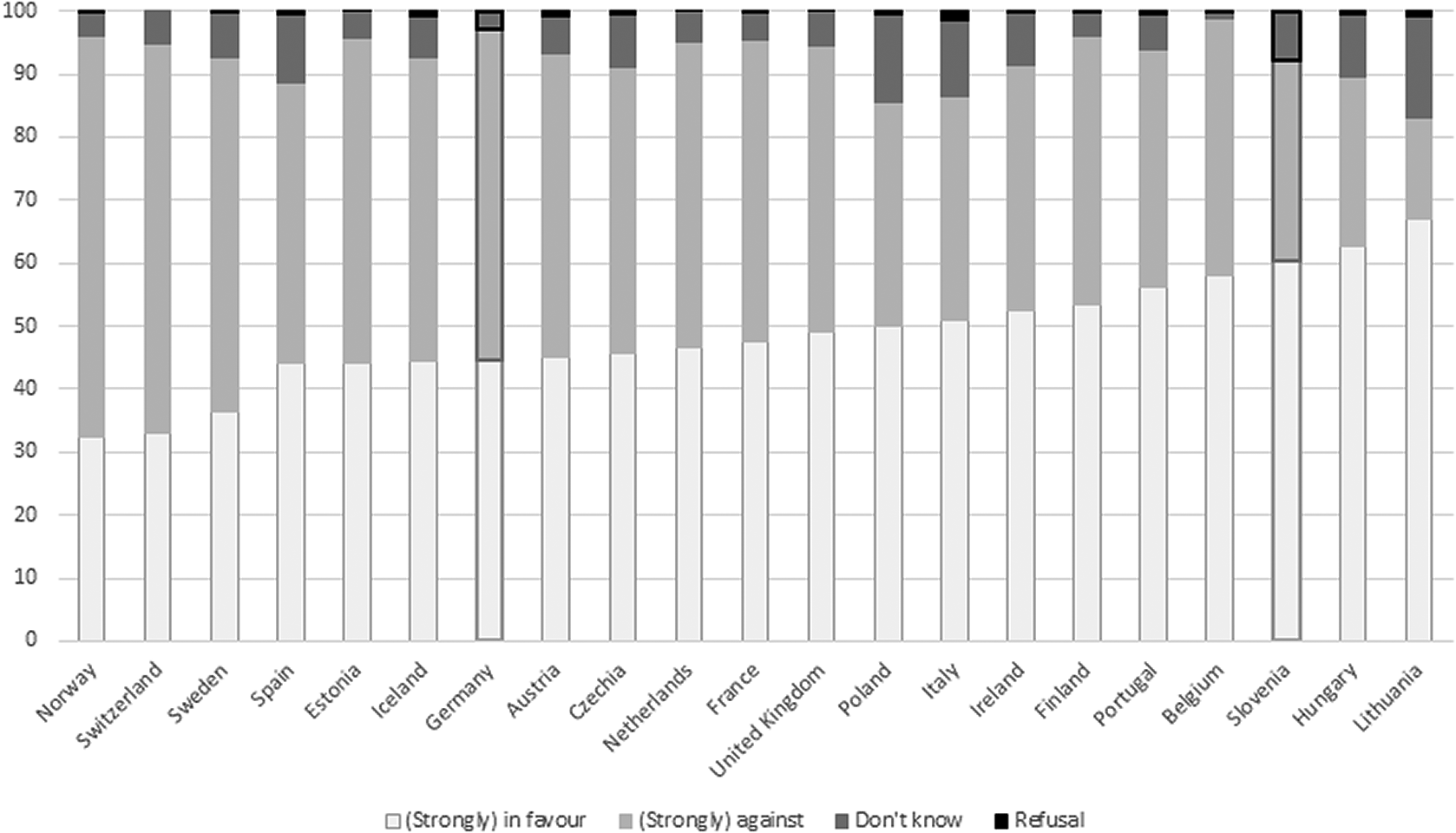

Figure 1. Share of respondents who would be in favour or strongly in favour of the introduction of an unconditional basic income (UBI). Source: ESS 2016 (weighted data).

In the last years, the literature on UBI has expanded from advocacy texts, critique and descriptions of the different approaches (Martinelli, Reference Martinelli2017; Spannagel, Reference Spannagel2015; van Parijs, Reference Parijs1997) to more empirically oriented debates. Particularly in the context of experiments such as in Finland or Kenia (Kangas et al., Reference Kangas, Jauhiainen, Simanainen and Ylikännö2019; Latour, Reference Latour2016) and Canada (Hamilton & Mulvale, Reference Hamilton and Mulvale2019), scholars have started to examine the practical implementations of a UBI, as well as economic and political, and effects on individuals. What is now a very new field is research on the social legitimacy of a UBI – a most important aspect taking into account the unique concept of social justice underlying the UBI. The emergence of this strand is particularly supported by the inclusion of questions on the UBI in surveys such as the European Social Survey (ESS) 2016, as several contributions in this special issue show. However, UBI itself is a complex and very different approach compared to the existing social security schemes, a fact that should be considered when interpreting any survey data. Not only might people not fully understand the concept they are asked to judge, their point of departure is also unknown by us: do they support the universalism of the approach? The unconditionality? What do they criticize? We argue that to understand the social legitimacy of the approach, it is vital to grasp what people’s understanding of the UBI is, what they expect from it, and why they reject or support it in light of their own perception of social justice – dimensions that are hard to capture with quantitative studies.

This is why our study seeks to complement the quantitative, survey-based studies on perceptions about the UBI from a qualitative perspective. We set out to study the social legitimacy of the UBI by qualitatively analysing large group discussions in Slovenia and Germany – two countries that constitute interesting contrasting cases, as will be outlined below. As we will outline in the following section, we follow the argument that (welfare) institutions embody conceptions of social justice and, as such, also have a preference forming impact on people’s moral stances towards income provision and social security. Hence, our article seeks to analyse how different concepts of social justice are linked to country-specific differences in people’s attitudes towards UBI.

Social justice and the moral economy of UBI

Social philosophers advocating the UBI have argued that it constitutes a very distinctive interpretation of social justice. According to van Parijs, UBI finds its rationale in the theory of citizenship of real libertarianism, which states that the most just society is the one that maximizes the least advantaged individual’s “real freedom”: the freedom to do whatever s/he might want to do (van Parijs, Reference Parijs1997). At the same time, real libertarianism sees equality as an endeavour to continuously improve the social position of the most disadvantaged (van Parijs, Reference Parijs1992), whereby it pursues the principle of equality of opportunities rather than equality of outcomes. In this sense, real libertarianism is a starting-gate theory that attempts to equalize individuals’ opportunities through compensation. Thus, it also seeks to incorporate the market (as a distribution mechanism) into the concept of social justice, leaving only inequalities for which the individual is not responsible in the domain of social policies (Anderson, Reference Anderson1999). This commitment to equality, along with the social policies needed to attain it (maximizing individual’s opportunities by implementing UBI), is intended to fulfil the concept of real freedom as one in which the individual is empowered to carry out their life plan in accordance with their own preferences and ideals and in the complete absence of state paternalism.

The UBI idea is in line with the traditional libertarianism approach in the sense that it emphasizes the right of every individual to natural resources, but the redistributive nature of the UBI is clearly in opposition to libertarianism. This redistributive dimension is, however, shared with egalitarianism, which emphasizes the need to compensate “undeserved bad luck.” However, as the outcome of the equalizing potential of UBI is limited, particularly due to its flat-rate benefits, egalitarians might also have some opposition to the idea of a UBI. Communitarians who focus on the best in society as a whole might also criticize certain aspects of the UBI approach, especially the lack of reciprocity. However, they might, at the same time, embrace other aspects, such as the potential to reduce people’s dependency on wage labour, as this would permit more time for communitarian responsibilities (Martinelli, Reference Martinelli2017, pp. 90–92). Briefly, the social justice rationale underpinning the UBI shares some fundamental commonalities with traditional concepts of social justice but also differs considerably from them.

Departing from this perspective, our argument is that if we want to understand people’s perceptions of UBI, we need to understand them as reactions to the genuinely new suggestions of the UBI – reactions that come from the perspective of other (already existing) concepts of social justice. According to Liebig and Sauer (Reference Liebig, Sauer, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016), perceptions of (social) justice in a society (1) vary according to the basic structure of a society and are thus historically contingent, (2) are reflected in the institutional design of society (ie welfare institutions, tax systems), (3) are socially conditioned and (4) can have social consequences in the sense that experiences of (in)justice affect attitudes and behaviour of individuals (Liebig & Sauer, Reference Liebig, Sauer, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016, p. 38). Hence, individual perceptions of social justice are interwoven in a complex web of social structure, institutions and individual (but socially conditioned) attitudes. Consequently, we argue that analysing people’s perceptions of a UBI alongside existing principles of social justice is vital to understanding the social legitimacy of the approach.

Here, the role of welfare institutions that determine how and to whom resources and chances are redistributed (such as social insurance or social assistance schemes) are particularly relevant in our eyes. They do not only most probably serve as a contrasting frame to which the UBI as a social policy measure is compared, they also fundamentally shape people’s perceptions of social justice, as the institutional setting in which people live also frames their attitudes considerably and strongly interacts with individual interests and values (Larsen, Reference Larsen2008; Liebig & Sauer, Reference Liebig, Sauer, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016; Mau, Reference Mau2003; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors1997). As Mau (Reference Mau2003) showed, institutions embody concepts of social justice, and they mediate and cultivate a corresponding normative repertoire. He argues that “institutions are not merely environments for gain-oriented attitudes since they embody conceptions of social justice; they also have a preference and taste forming impact on people’s moral stances. Therefore, what people regard as fair and equitable welfare burden and welfare benefit varies significantly with regard to different welfare sectors and welfare regimes.” (Mau, Reference Mau2003, p. 195) Sachweh (Reference Sachweh, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016) takes up this argument and develops a more detailed perspective on the embodiments of social justice in different welfare institutions. He argues that the different approaches towards social justice are related to basic principles such as equality, need and merit (Sachweh, Reference Sachweh, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016), which play different roles in different welfare setups (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). To be sure, there is not one concept of social justice that is represented in all the different measures and policies that can be found in the complex welfare setting of a country – different policies might represent different routes and perspectives. Nevertheless, there are usually still dominant patterns: For instance, the social-democratic approach to welfare emphasizes the relevance of equality of outcome, the liberal approach focuses on need and merit, and the conservative approach on merit and equivalence (Sachweh, Reference Sachweh, Sabbagh and Schmitt2016, pp. 298–299). Similar arguments were brought forward by Arts and Gelissen (Reference Arts and Gelissen2001) who also included the southern model of welfare states, which resembles the conservative one in its emphasis on status protection and reciprocity (ie highlighting individual meritocratic achievements and the principle of equivalence) but leaves large shares of social protection to the family. Neither Sachweh nor Arts and Gelissen have discussed the post-socialist welfare model, but from what we know, the post-socialist countries with welfare systems based on the Bismarckian tradition – such as Slovenia, Hungary, Czech Republic and Croatia – would emphasize principles of reciprocity along with equality (of outcomes), which are rooted in the state socialist welfare model (Deacon, Reference Deacon2000; Kolarici, Kopac, & Rakar, Reference Kolariči, Kopac, Rakar, Schubert, Hegelich and Bazant2009; Rus, Reference Rus1990; Stambolieva, Reference Stambolieva2016).

Based on these moral economy arguments regarding the embodiment of social justice principles in welfare institutions, we can expect existing (welfare) institutions to work as the point of departure and general baseline for people’s judgements of the UBI. This means they will assess the UBI approach against their (individual but institutionally framed) views regarding equality, meritocracy, need or reciprocity. For our two countries under study, this means that we can expect people in Slovenia to emphasize the role of equality as well as universality and hence be more supportive of the universality embedded in the UBI. Universalistic principles are rooted in the Slovenian approach to providing welfare, stemming from the socialist era and its emphasis on achieving equality as the primary goal of socialist welfare states (Rus, Reference Rus1990). This becomes evident in regard to the universalistic provision of welfare services, such as health care, child care services, education (also higher education), as well as some additional benefits (eg for children) (see Kolariči et al., Reference Kolariči, Kopac, Rakar, Schubert, Hegelich and Bazant2009). However, in Slovenia, the welfare system is also linked to the meritocratic Bismarckian tradition of social insurance, evident in, for example, the pension system and unemployment schemes. Additionally, a few of the recently present more universalistic principles have been abandoned in the last decades and more conditionality was introduced (see Ignjatovič & Filipovič Hrast, Reference Ignjatovič, Filipovič Hrast and Theodoropoulou2018).

In Germany, we can expect people to put a focus on merit and status maintenance, and hence probably criticize the UBI for its universality. Despite some in-depth reforms in the last decades, the German welfare system is still rooted in a Bismarckian tradition of social insurance. This status-preserving system is still prevalent in the pension system and also in the unemployment protection scheme, albeit the Hartz-reforms in 2004 added a tax-financed, flat-rate unemployment protection layer and a generally stronger emphasis on self-responsibility was introduced (for an overview: Heuer & Mau, Reference Heuer, Mau, Taylor-Gooby, Leruth and Chung2017). Research showed that – while increased individual responsibility was largely accepted – the shift from status preservation towards tax-financed basic protection was received sceptically among the German population (eg Nüchter et al., Reference Nüchter, Bieräugel, Glatzer and Schmid2010; Sachweh et al., Reference Sachweh, Burkhardt and Mau2009).

The two countries constitute interesting contrasting cases when it comes to support for a UBI as measured in the ESS: Figure 1 displays the share of respondents per country who answered the question on support of a UBI in the ESS 2016 with “(strongly) in favour,” “(strongly) against,” “Do not know” or refused to answer. As we can see, Slovenia is one of the countries with relatively high support [60.5 per cent are (strongly) in favour] while support in Germany is considerably lower [44.7 per cent are (strongly) in favour]. Interestingly, in Slovenia, the non-response rate (ie “Do not know” or refusal) is with 7.9 per cent much higher than in Germany (3 per cent).

In both countries, UBI has been the subject of relatively vibrant debates in the last years. In the 1990s and 2000s, the discussions were mostly limited to academic circles and non-governmental initiatives and particularly pushed forward by a few private advocates of the approach. In the last decade, interest in the UBI reached the political realm, and the concept found support, especially on the left of the political spectrum. In Slovenia, some political parties reacted to the initiatives by non-governmental political actors (eg section for promotion of UBI – slo. Sekcija za promocijo UTD) and responded to the favourable public opinion towards a UBI. In 2018, the state set up a feasibility study on UBI (Boljka et al., Reference Boljka, Trbanc and Črnak Meglič2018). UBI has been seen as a political niche for several non-parliamentary political parties who have used it as one of their main campaign pillars before the parliamentary elections. In general, the established political parties on the left and those on the political right have predominantly ignored the UBI.

The situation in Germany has been similar but the lower non-response rate in the ESS might point towards a higher public salience of the topic. Smaller political parties in Germany have reacted to the initiatives put forward by non-political actors [eg the initiative “Mein Grundeinkommen” (“my basic income”); Mein Grundeinkommen, Reference Grundeinkommen2020] and to its popularity among citizens (Adriaans et al., Reference Adriaans, Liebig and Schupp2019). Today, the political parties Die Linke, Die Grünen and the Piratenpartei – despite inner-party divides over the idea – have all established UBI-working groups, frequently discuss the topic and have prominent advocates in their rank. In addition, a one-topic party (Bündnis Grundeinkommen) was founded in 2016 and sought to promote the UBI at the political level in all federal states in Germany. In both Slovenia and Germany, public interest in UBI has been further boosted by the Swiss referendum on UBI and the experiment in Finland.Footnote 3

Methods

In order to study people’s perceptions of the UBI, we drew on qualitative data from large group discussions gathered in the context of the NORFACE-funded research project WelfSOC.Footnote 4 The qualitative data allows for insights into people’s sense-making and justifications behind their attitudes towards the UBI – something which is most suitable for us as we seek to understand the link between judgements and perceptions of the UBI in light of institutional settings. The group discussions were conducted in five countries (UK, Slovenia, Norway, Denmark and Germany), and the UBI was discussed in two of them, which shall be analysed here: Slovenia and Germany. The two countries under study represent two contrasting cases, as the countries constitute different welfare systems and also show different pictures regarding public support of the UBI in surveys (cf. Figure 1). While Germany is among the countries with the lowest support (46 per cent are in favour or strongly in favour of the introduction of a UBI), Slovenia is among those with the highest support (65.7 per cent).

We drew on two different datasets in both countries: one consisting of transcripts of large group discussions called democratic forums (DFs; for details on the method and design see Taylor-Gooby & Leruth, Reference Taylor-Gooby and Leruth2018), the other of transcripts of traditional focus groups (FGs). Combining the two datasets that both addressed the same research interest (ie people’s attitudes towards the future of their welfare state) and drew on very similar data gathering techniques has the benefit that it increases the breadth of our database and allows a certain validation (as similar patterns of debates emerged in the two datasets in each countries).

The DFs took place on two Saturdays in autumn 2015 in Slovenia and Germany. On both days, 34 and 37 people came together in Germany and Slovenia, respectively, to discuss the “welfare state of the future” in their country. The participants were recruited by professional research agencies to reflect national demographic characteristics regarding gender, age, educational qualification, employment status, household income, family status and children in the household, migration background and political party preferences.Footnote 5 During the DF, they were split into three sub-groups with about 10–12 participants in each group. There were also two plenary discussions per day. The groups spent the majority of each day discussing several topics (such as unemployment, pensions and healthcare) under the bigger headline-question how the welfare state in their country should look like in the future. The DFs were only loosely moderated by professional moderators, and in both countries, a large variety of themes were raised by the groups in the context of the mentioned topics. UBI was one of those themes raised by participants (and not introduced by moderators) in both countries, which indicates the salience of the topic. While in Germany the UBI was discussed in two sub-groups, in Slovenia it appeared in only one sub-group. In both countries, well-informed and UBI-supporting participants brought up the topic and explained it to the other participants.

The FGs were conducted in autumn 2016. In each country, five FGs were formed (each lasting 2 h) with different groups that were socio-economically relatively homogenous (middle class, working class, pensioners, under 25 and women with care duties). As discussion stimulus, the participants received different vignettes of welfare target groups (eg unemployed, low income, migrant; for further information on the treatment see online appendix). For both Slovenia and Germany, we have used data from only the middle-class group as this was the only group in which UBI was raised as a topic by the participants.Footnote 6 Similar to the DFs, well-informed participants explained it to the other participants (and it was not introduced by moderators). For the FGs and the DFs, this implies that no pre-defined UBI-scheme was in the focus of the discussions, but instead the abstract principles of unconditionality, universality, flat-rate payments (sometimes a prominent amount was mentioned as an exemplary sum, like 1,000 € in Germany) and sometimes the abolishment of other social benefits. This triggered debates on a relatively abstract level so that people’s judgements of the underlying principles could be observed.

Audio and video recordings were made of both the DFs and FGs, transcribed and translated into English by the professional research agencies. For analysing the debates on UBI, we selected in a first step those sequences from the transcripts of the DFs and FGs where UBI was discussed, plus parts of the preceding discussion in order to understand the context in which the UBI was brought up by participants. In the second step, with the help of NVivo, we applied the first round of coding with a rough deductive set of codes, highlighting those parts of the data where arguments for and against the UBI were raised, including the expression of problem perceptions and reasons why a UBI should or should not be introduced. In the second round of coding, we used coding categories related to the principles of social justice within the arguments for and against a UBI: equality (of outcomes/of chances), solidarity/social cohesion, freedom (of choice/freedom from), value of work, conditionality, need and reciprocity. In addition, we took into account non-social justice-related arguments such as those on administration or financing.

Analysis

Germany

In Germany, the contexts in which UBI was brought up by the participants, as well as the level of support, were similar across all breakout groups of the DFs and FGs. In general, people raised the topic both in the context of macro-economic debates [“Every time we add more burden to the social welfare system, it accelerates its collapse (…); we have to build a completely new system.” (P34, DF)] and in discussions focusing more on the individual level, such as health issues and gender inequality [“They do not need to burn out and can live as healthy people” (P04, DF)]. Consequently, the statements by participants supporting the UBI concentrated on points such as welfare financing and administration, economic inequalities, care work, the motivation to work and the value of certain jobs. Similar to the political and expert debates, the idea that a UBI could help build a sustainable social security system while at the same time solve administrative problems of the tax and welfare systems was frequently raised by the advocates of the approach:

The shadow economy would fall away because no one would need to avoid the social welfare contributions or rules anymore (…). (P04, DF)

I have to ask whether I’d rather pay the money for the bureaucracy, or whether I’d rather distribute that money either in the form of minimum pension or unconditional basic income. (P24, DF)

The debates on care work, the value of jobs and motivation to work resemble the points raised by prominent advocates when highlighting the potential of a different approach towards work such as that of decoupling paid labour and securing subsistence. Here, especially the chance to valorize currently unpopular jobs (as higher wages would emerge for them), the individual freedom to opt for unpaid care work or stay at home for other reasons, and a changing attitude towards work that would also provide people with greater freedom were mentioned by the participants:

But this [the UBI] might lead to re-categorisation where the hairdresser earns more than this or that group… (P 31, DF)

Then you have a completely different motivation for working& (P15, DF)

But every housewife and mother would have a right to that so that they can stay at home. (P23, DF)

The critical voices were mixed and questioned some basic assumptions of the UBI approach. Participants raised fundamental concerns with regard to the practical dimension as they doubted whether the introduction of a UBI would mean a “real system change” or whether its implementation would be feasible. In this context, participants also feared that the introduction of a UBI in one country would lead to a welfare magnet problem:

But what would happen globally if here in Germany we would all get 1,000 euros as a basic secure income without any conditions? (P28, DF)

But you have to consider that if I’m a landlord and I know that everyone is running around with 1,000 euros in their pocket, then I’m going to want to take advantage of that. (P34, DF)

Other frequently raised doubts and critical points concern the issue of motivation to work. Here, the topic of “welfare moochers” was crucial:

They [the “moochers”] buy the newest mobile phones, and then, by the middle of the month, they have no money left and go to get additional state funds, because they can’t just let them starve. So (…) I’m very much against the concept of unconditionality in this regard. (P32, DF)

Turning now towards a social justice perspective on the debate on UBI in the German DF, it becomes clear that freedom is privileged over equality. Although a few statements pointed towards greater equality of chances through the introduction of a UBI [“If I want to send my child to a private school, then I have to earn enough money to pay for this, and that is unevenly distributed. If we were to go with (unconditional) basic income, then people have the same chances.” (P23, DF)], the advocates did not strongly promote the equalizing potential of a UBI. Furthermore, this equalizing potential was also strongly questioned by many sceptics who pointed towards the inability of a UBI to achieve equality of outcomes. [“If every citizen gets a thousand euros, then everything would just get more expensive (…).” (P16, DF)].

With regard to freedom, the picture is different. Statements highlighting the freedom of choice were frequently made by supporters of the approach [“That’s not a bad idea, because the individual has to decide how he or she wants to live.” (MC7, FG)], and – except with regard to the moochers’ debate – not questioned by more critical participants. The most relevant positive arguments with regard to the freedom of choice were higher motivation for work and greater choice with regard to care work and other family-related decisions. Greater individual freedom with regard to family and care topics (and also health) was not only brought up in the context of freedom of choice but also with regard to “freedom from.” Here, relief from economic pressure was seen as an opportunity to take decisions more freely:

If my ex-husband, who was a craftsman, and I back then, had been provided a basic income by the state in the same amount, we’d only have had to decide which one of us would work a bit extra, and I would not have had to go to work while still breastfeeding. (P05, DF)

Most interestingly, the high value that the German participants imposed on individual freedom in the context of the UBI debates finds its limit when it comes to reciprocity. The narrative of the active individual who should not put a burden on society by being lazy but instead contribute to the “common good” in exchange for receiving social support was very strong throughout the entire discussion and also emerged in the context of UBI. This results in a clear rejection of unconditionality in combination with a general (and not work specific) demand for proof of activity:

The condition I would connect with that is if I’m going to be getting social support in the broadest sense, then I should have to do something for the state. It can’t be that I just open up my hand and the state gives me something. (P32, DF)

According to my way of thinking, when I’m hungry, then I have to get up and plant a tomato plant or buy something – I have to actively do something. It doesn’t just show up on its own. (P31, DF)

In some cases, the demand for proof of an activity was also linked to a call for means testing or a coupling of the social right for UBI to German citizenship, as this would exclude people from receiving a UBI who had not contributed earlier:

You have to do something, earn something, work at something.” Unknown: “Or at least with some kind of verification or proof of need. (P18, DF)

No, they’d have to earn it in a sense. It would start after they get German citizenship. Without that, they’d not get this money. (P23, DF)

Besides reciprocity, the notion of merit was a frequent baseline of critical statements towards a UBI – and it relates to the above-mentioned low relevance of equality in the debates. Participants not only questioned the equalizing potential of a UBI, several also stated that equality of outcomes was not in line with their perceptions of how society should work, and that different achievements, such as (educational) investments or different work efforts, would not be reflected:

If we’re talking about unconditional basic income, then I’m in favour of saying that we’re an achievement-based society, and that is the point where I get stuck (…). (P17, DF)

(…) some people work hard and get 600, and others stay at home and get 900 for doing nothing. So, I’m totally against it. (P10, DF)

The emphasis on merit and achievements became particularly pronounced in the following dialogue from the focus group. Participants first stated that “it should be the same for everyone” but finally concluded that an expensive or time-consuming education (and in another statement also special performance or having many children; MC-9, FG) would justify a higher UBI:

MC-3: “It should be the same for everyone, regardless of whether they were a hairdresser and only earned 1,200 euros, they also need to get their 800 a month just as the other person starting at the basic income level who used to earn 4,000 euros. They start at 800 and then one can see perceptually that if they did more, then they might get another 400.” MC-9: “What more might they have done or contributed?” MC-5: “Well, if they had a more expensive or time-consuming education, for instance, you would have to take that into account. Otherwise, no one will want to take the trouble to pursue a more elaborate education if they were going to get the same money in the end anyway.” (FG)

In a nutshell, it can be stated that in the German DFs and FGs a strong emphasis on individual freedom in the supporting arguments can be observed; however, equality was less pronounced. The critical voices raised concerns with regard to unconditionality and equality of outcomes, while reciprocity and meritocracy were highlighted as crucial fundamental principles. From the focus on merit and reciprocity, two general lines of argument emerge that are linked to both equality and freedom: as different investments and achievements are stressed as particularly relevant, people argue that both equality and freedom should be restricted (ie for freedom: conditionality, needs tests, exclusion of migrants; for equality: different benefit levels according to different investments/achievements).

Slovenia

The arguments from the DFs and FGs in Slovenia followed a very similar line, focusing on the benefits of universal transfers that would ease the bureaucratic burden of a complex welfare state and improve its efficiency and quality:

It [the UBI] allows you to cross a bunch of things out. (P67, DF)

And the social work centres might finally start to deal with social problems and not with who gets what and how much. (P4.5, FG)

In addition to this and also quite relevant were the arguments that universal UBI would reduce corruption and abuse of benefits. The abuse of benefits was, in general, a large part of the discussions, and a UBI was seen as one of the solutions for this issue:

And the sole proprietors also could not profit from working illegally. They now work illegally in order to not have to pay for child daycare. So, if they don't have to do those things and they receive the social benefits instead …, there would be none of that anymore. They would receive 500 euros whether they would be working or not, end of story. It would be better if they would work, wouldn't it? (P69, DF)

Another crucial point in the discussions was the social cohesion argument, stressing the idea that all parts of society need to support each other, and each member is valued. This argument was, therefore, linked not to the practical functioning of a welfare state but to abstract solidarity needed for the common functioning of the society, stressing the universalistic principle:

Well, it fits with this as well. If all contribute…, if we all live like an organism, the state is that, regardless of whether it's about our hands or our heads, we are all drawing from it; we are all using a certain base in order to be able to live and function. So, my suggestion would be to have a common base, how should I put it, something that certain states already have. (P73, DF)

(…) if this [the UBI] were the case (…), perhaps we would prefer to think about the quality of life, about what else you can offer to this country, to society, right? (P73, DF)

Besides support, negative reflections and critiques of a UBI also came up during the discussions. The strongest critique was the worry about participation in the labour market and the motivation to work. Critical voices put forward the arguments that under these conditions, people would lose their motivation to work:

No, no, they will no longer be working, fifty-fifty, fifty percent would stop working and fifty percent [would work]. (P65, DF)

In the context of these critiques, people extensively discussed the level of UBI and largely agreed that it should be set low enough to still stimulate work participation:

But then the difference between the minimum wage and this benefit should be, let's say, very big (…) so as to not, I don't know, encourage laziness. (P65, DF)

These worries about people’s laziness were strongly contradicted in the discussions, forming probably one of the strongest divisions within the discussions on UBI in Slovenia:

Why wouldn't they go to work? They weren't made to be lazy. (P73, DF)

But, these social transfers are considered OK. And nobody is upset about there being so many types of social transfers. And nobody is upset about receiving them…. And people receive the benefit and a subsidy for food, and I haven't noticed anyone quitting their job over this. (P70, DF)

In analysing the arguments in Slovenia, it is evident that the supporting arguments rarely drew on the “classic” UBI reasoning of equality (“of chances”) and freedom (from constraints and to do what one likes). Instead, the practical arguments that dominated the debate were that a UBI would substitute an overly complex welfare state, reduce social spending and help to control benefit abuse or undeclared work. However, despite not being in the forefront, equality and freedom arguments are visible.

As for the dimension of freedom, the positive effect of UBI on enabling personal choice, especially in relation to the labour market, was indeed put forward by a few participants:

I think that society would function in a much more relaxed way, or one may say, “I’ll take 5 years and do this and that,” or “I'll be researching something and then I'll get a job again”. One would not be under pressure; oh my, a job, I'm waiting for a job, I have been waiting for one for 2 years. (P68, DF)

In fact, in that case, people are more active because they have more options. They might even go to educate themselves and do what they really want. That makes them more productive. This means that the welfare benefits actually do not make people dependent and do not make them lazy. (P4.7, FG)

However, the freedom of choice in the view of the participants did not seem to be rooted in the arguments linked to individual decisions. Instead, they were related to the freedom of doing something good for society and, therefore, this freedom is linked with reciprocity:

It's, yes, yes. For example, one of the family members is unemployed and would be receiving universal income, the other would have a job, and that would be enough. They would have more time for & Exactly, they could do more charity work, humanitarian work, public works and so on. (P68, DF)

A similar narrative can be found for equality arguments. It was less the idea of equality of chances that would be reinforced by the UBI but the idea of universality in the sense of equality of treatment. Here, the above-mentioned arguments of social cohesion and collective solidarity are particularly relevant. Equal treatment of each and every person in society was put forward, expressed in the equal right to the same amount of UBI:

Which means that we are all going to have the same, all of us, everybody will be on the same income. (P69, DF)

But then we come to a very good question, why would this apply only to healthy 70-year-olds? Why wouldn’t it apply to all? For all people, for each? From the newborn until death. Then, say at the age of fifteen or eighteen you are able to work, why wouldn’t you receive a basic income? Why should this affect your primary income if you work more? (P4.7, FG)

The notion of universalism becomes crucial as a basic welfare state principle. The arguments for such universalism seem to be grounded in the idea of equality as a value in itself. Equality was seen at the starting point as assuring a basic minimum that would be necessary for an individual to live a decent life, but not in the sense of a levelling and equalizing effect, that is, equality of outcome:

It's not about that people do not have the same paycheques. (P65, DF)

No, no, no, no, no. It's not a levelling, no, no, no. (P67, DF)

No, it’s enough to make ends meet so that you don’t have to be on minimum wage. You don’t need social transfers… (P73, DF)

Besides universalism, the second principle that was very salient in the debates is reciprocity. The above-mentioned freedom of choice argument for the introduction of a UBI often seemed to be linked with the idea of obligations of all individuals to return something to society (eg humanitarian, voluntary work). This also becomes visible in the debate about “laziness” where several participants expressed their concerns that the introduction of a UBI would demotivate people to work and hence would lead to an exploitation of the society.

Interestingly, need to be played a certain role in the basic arguments for universalism when people argued that UBI addresses the basic needs of all the people to be sustained and having their needs fulfilled as members of the society. However, needs testing was not part of the conditionality imposed on the UBI. The discussion on introducing conditions on the receipt of a UBI was very limited, mainly in the form of controlling what the income was spent on through a voucher system.

In a nutshell, we can conclude that the support for a UBI in the Slovenian discussion groups was mainly linked to an improvement in the efficiency and transparency of the welfare state. From a social justice perspective, freedom arguments were much less pronounced than equality arguments. However, equality was not understood in the sense of an equality of chances or outcomes but as universalism and equality in treatment. The few freedom of choice arguments were furthermore linked to a reciprocal idea of the individual giving something back to society. As we will discuss below, this relates to a strong role of the collective in the Slovenian discussions.

UBI in Germany and Slovenia – a comparison

The previous paragraphs provided an insight into our analyses of the group discussions on UBI in Slovenia and Germany. The analyses revealed a number of similarities between the two countries: in both countries, a UBI was perceived as a potential option for future welfare policies and was generally supported by several participants (although also heavily criticized by others). In their support, the participants from both countries emphasized very similar administrative and procedural arguments: they stressed that the UBI could be an option to achieve welfare state sustainability, reduce overly complex welfare state institutions, help ban the shadow economy and make welfare abuse obsolete.

However, besides the similarities, there were also fundamental differences in the debates in the two countries, particularly when interpreting them from a social justice perspective. As outlined initially, the UBI can be understood as being rooted in the social justice concept of “real libertarianism” (van Parijs, Reference Parijs1997), which seeks to combine freedom (in the sense of freedom to do whatever one might want to do) and equality (in the sense of an equality of opportunities) in a specific way. Now, our data shows that the debates in the two countries emphasize these concepts in rather different ways – and we argue that this can be linked to different institutional setups in the two countries, as these embody specific concepts of social justice. In Germany, the dominant narrative of the supporters of a UBI was one of individual freedom. Although equality (of opportunities) arguments were also raised, the emphasis clearly laid on freedom when participants stressed the chances of relieving individuals from economic pressure or increasing individual motivation by allowing greater choice with regard to job, family and health decisions. In Slovenia, the picture is very different. Here, we observed the dominance of equality arguments over freedom arguments. However, equality was only partly seen as equality of chances but mostly as equality of treatment. The basic narrative was that every person is part of a collective, the society and as such has the same right to a basic subsistence by the state.

As we showed in our analyses, these fundamentally different approaches towards the social justice roots of UBI are linked to different basic welfare state principles that people apply when judging the UBI. In Germany, participants frequently brought up arguments for both reciprocity and meritocracy – which is clearly in line with the above-mentioned, still prevalent principles of the Bismarckian social insurance system in Germany. The participants explicitly wanted different achievements and investments to be reflected in the access to and amount of benefits. Furthermore, they demanded proof of activity as a condition for receiving a basic income. In Slovenia, the dominant welfare state principle in the UBI debate was one of universalism, which we can link with socialist past and its universalistic approach to welfare provision. As already outlined, the participants frequently highlighted that every individual is important for society as a collective and should be supported by it. Hence, they strongly supported an equal treatment in the sense of equal benefits for all. However, at the same time, a certain notion of reciprocity was also applied in the participants’ judgements of the UBI, which we can link with the Bismarckian tradition of social insurance systems and meritocracy also present in Slovenia. However, this was different compared to Germany: Reciprocity in Slovenia was seen as a moral implication rather than a procedural expectation (as in the activity proofs in Germany) in the sense that people should give something back to society, like in community work.

As already discernible, the different perspectives on the UBI in the two countries under study – linked to different (interpretations of) basic welfare state principles – are related to different kinds of critique of the UBI:

-

• In both countries, motivation to work was raised as a crucial concern. While in Germany, the participants demanded proof of activity as a condition for benefit receipt, in Slovenia the participants pleaded for a low level of benefits for all in order to maintain motivation. Hence, for several German participants, the unconditionality of the UBI approach constituted a problem, while this was not the case in Slovenia.

-

• We also observed diverging notions of reciprocity: the responsibility of the individual towards society in Germany (and thus critique of unconditionality) and the responsibility of society towards the individual in Slovenia.

-

• In Slovenia, the participants highlighted universalism and strongly supported equal amounts of benefits for all, while in Germany arguments of merit and status preservation came in. This led some German participants to criticize the UBI for its universalism when demanding different levels of benefits for different achievements and investments.

-

• The support for equal benefits for all was in the Slovenian debate also linked to the principle of need, although not for requesting conditionality but – rather contrariwise – as an argument for unconditionality, as the UBI would address the basic need for all members in society. In the German debate, arguments referring towards need were not salient.

Conclusion

To better understand the link between the social justice paradigms that are rooted in existing welfare institutions and the social legitimacy of the UBI, our study analysed group discussions in Slovenia and Germany where participants discussed – among other topics – the UBI. Our basic expectation that people would interpret, perceive, judge and discuss the UBI on the basis of their own experiences and in the framework of their own moral economy can be confirmed for the analysed debates in Germany and Slovenia. In the dominant lines of arguments in Germany, we can clearly see the well-known basic principles of the conservative welfare state: Participants stressed the role of achievements and investments for benefit receipt and frequently referred to ideas of merit and reciprocity, hence following a clear logic of status preservation and work ethos. This dominant repertoire seems to have led their perceptions of the UBI and also framed their judgements of the approach, as they particularly criticized the principles of unconditionality and universalism. In Slovenia, the principles of universalism and unconditionally were supported while also stressing reciprocity. The former seems to be rooted in collectivism of the past socialist system with the universal inclusion of citizens and the equalizing principles as the main goals (Kuitto, Reference Kuitto2016; Rus, Reference Rus1990).Footnote 7 However, the lack of focus on the equality of outcome could be seen also more in line with the conservative, Bismarckian tradition of the Slovenian welfare state, that tends to valuate more the meritocratic link of contributions and outcomes. The basic agreement with universalistic principles of UBI, as well as arguments that put forward the potential inefficiency and corruption within the current welfare state arrangement might also be important in understanding the relatively positive views towards UBI indicated in this study (and also in survey-based analyses of attitudes towards the UBI). Unfortunately, due to data limitations, we were not able to include other welfare states in our analysis. As our study strongly points towards a crucial link between existing systems and people’s perceptions of the UBI as a new social policy approach, it would be highly interesting to see whether debates on the UBI in other welfare regimes would follow similar patterns.Footnote 8 Here, we would, for instance, expect discussions in liberal countries like the UK to support the freedom dimension of a UBI but raise critiques for the lack of means testing and lack of meritocratic gains. For Scandinavian countries, we would expect to find criticism of a UBI for missing focus on the equality of resources and outcomes. Such studies should in our eyes adopt a more traditional “attitudes” research approach and directly prompt people’s perceptions of the UBI. While our design, that focused on a general “future of the welfare state,” was highly informative for providing a broader and interconnected picture of people’s attitudes towards different dimensions of the welfare state, it is not suited to unravel more specific, fine-grained and systematic insights. Furthermore, the experimental design of the group discussions might have led to group-specific processes and other selectivity issues that could not be captured in the present study but might have influenced the results.

Hence, future research will be needed to test the above-mentioned expectations, validate our findings, and to provide more in-depth insight into the social legitimacy of the UBI and its relationship to existing welfare institutions. Such insights are not only highly interesting from an academic point of view but also provide valuable insights for the advocates and opponents of a UBI. They would permit the identification of the different challenges that the UBI might be confronted within different settings, allowing these challenges to be addressed in an adequate manner. In this regard, our qualitative and small-scale study can be a starting point for hopefully broader research on the social legitimacy of a UBI, both quantitative and qualitative.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no financial interest or benefit that has arisen from the direct applications of their research.

APPENDIX

Extended information on data collection

The data analysed in the article were gathered in the context of the NORFACE-funded WelfSOC project; a project interested in qualitative research on citizens’ attitude towards the welfare states, particularly their aspirations for the future of the welfare state in their country (blogs.kent.ac.uk/welfsoc). Under the lead of the coordinator Peter Taylor-Gooby (University of Kent), national teams in five European countries (UK, Slovenia, Denmark, Norway and Germany) conducted two different types of group discussions in each country: FGs and Deliberative Forums (DF). Both forms of group discussions had a specific setup with regard to group composition, duration and moderation, but had at its core the same overall topic: the future of the welfare state in the respective country in 2040. In both setups (FGs and DFs), participants in all five countries discussed this overall topic, and recruitment procedures, moderation guidelines, organisational setup, etc. of the group discussions were the same in each country; agreed upon among the five national research teams. Based on the agreed structure and in close cooperation with the national research teams, professional research agencies organised the recruitment, organised the events, moderated the discussions and provided audio- and video-recording as well as transcripts and English translations of all group discussions.Footnote 1

In the FGs, the UBI was discussed in four of the five countries under study: Germany, Slovenia, Denmark and the UK. In the DFs, it also came up in three countries, namely UK, Slovenia and Germany. Both in the FGs and the DFs, the UBI was brought up by single participants as a potential option for future social policies, and then explained by those who knew more about it to the other participants. Researchers and moderators did not intervene by mentioning the topic or providing further information. In the FGs, the debates on the UBI were – given the design of the FGs, see below – necessarily quite short. In the UK DFs, the discussions on the UBI evolved mainly around different models and practical issues and were then dropped quickly (mostly due to time constraints and other topics coming up), while in Germany and Slovenia, the discussions went further and participants engaged in lively debates how they perceived the UBI.

For Germany and Slovenia, the databases with regard to discussions on the UBI within the DFs and the FGs are hence highly comparable in scope and focus and provide material rich enough for a sound analysis. As these two countries also constitute two contrasting cases when it comes to quantitative surveys on preferences towards the UBI (see main article), we chose to look closer into people’s perceptions of the UBI in Slovenia and Germany. The fact that the UBI was only discussed more extensively in these two countries is in our eyes a matter of contingent circumstances and should not be interpreted in the sense of a lower salience of the topic in the other countries (at least not on the basis of our data). In the following paragraphs, we will provide detailed information on data gathering and data processing the DFs and the FGs in the two countries.

The deliberative forums

The DFs took place in November 2015 in Ljubljana and Berlin for two full Saturdays (November 14th and 28th in Ljubljana, and November 7th and 21st Berlin) and were organised by the research agencies Aragon (Slovenia) and IPSOS (Germany). In Germany, the DF took place in the facilities of the Humboldt-University, and in Slovenia in the “M hotel.” The recruitment was organised by the research agencies, using professional recruitment databases. The participants received a financial incentive after the event (Germany: 280 €). Participants had been recruited with the aim to assemble a “mini-public” roughly representative of the population the two countries, with recruitments criteria being based on gender, age, educational qualification, employment status, family status, children in household, house-hold net income, migration background, and political orientation (see list of participants below). In Germany, 34 people showed up and participated in the DF, in Slovenia 37. The participants received an incentive for their participation (280 € in Germany, 100 € in Slovenia).

The structure of the DF in both countries was the same. When participants arrived at the venue on day 1, they were welcomed and given a survey questionnaire with socio-demographic questions and items from the ESS welfare attitudes module (ESS Round 4, 2008) as well as items from the International Survey Social Programme (ISSP) and by the WelfSOC co-ordination team (eg on parental leave).Footnote 2 A morning plenary session followed with a brief introduction to the format and the topic, and a brainstorming on associations that participants have when they hear the word “welfare state,” and what they seem as relevant for discussion in the DF. Moderators and researchers grouped the topics during a short break and distilled overall topics on which participants could then vote. The five most prominent topics were selected for further discussion on day 1. In Slovenia, these were health, employment, education and early education, elderly care, and values, rights and duties. In Germany, participants had selected the topics inequality and basic social security, labour markets and employment, families, retirement and intergenerational issues, health care, and immigration and refugees. The selected topics were then discussed in three breakout groups per country (11–14 participants per breakout-group).

In both countries, the participants were allocated to the three breakout groups randomly but with an eye towards creating a broad mixture of persons regarding age, gender, educational qualifications, etc. Furthermore, each breakout group had a “core group” of the few participants from a specific socio-demographic group: (1) self-employed persons (five in Germany and three in Slovenia), (2) persons from ethnic minorities (seven in Germany and one in Slovenia) and (3) unemployed persons or persons in precarious employment (five in Germany and three in Slovenia). During the DF, groups were only referred to by a randomly assigned colour and participants seemed not to be aware of the allocation criteria. In Germany, the UBI was particularly discussed in the breakout-group with the oversampling of persons from ethnic minorities (as here an advocate of the approach was present who introduced it and mentioned it frequently; not from an ethnic minority) and in the group with the oversampling of self-employed persons (here, several participants were aware of the approach). In Slovenia, the UBI discussion was also predominant in the breakout group with an oversampling of participants from ethnic minorities, and due to the formation of the proposal, this issue was also raised at the plenary session and shortly discussed by all participants.

During day 1, the participants discussed in the breakout-groups the five selected topics, with only loose moderation by professional moderators from the research agencies. Members of the research teams were present in the rooms but did not intervene. In the afternoon, all participants came back to a plenary session where they exchanged views and discussed the in their group’s eyes most important topics.

Between day 1 and day 2, the recruitment agency sent the participants a document with background information (“expert input”) from the research teams. This information was explicitly focussing on five topics that had been selected by all WelfSOC researchers in advance, in order to have the same topics for discussion on day 2 in all five countries. These topics were: work and occupation, inequalities, immigration, gender equality and intergenerational equality. Day 2 started with a plenary session and an expert presentation by members of the research teams, followed by a Q&A session. Afterwards, participants again gathered in their breakout-groups and discussed the five topics selected for day 2. The groups were asked to formulate a few policy guidelines for each of the five topics that should be brought to the plenary session at the end of day 2. In this plenary session, the policy guidelines were briefly presented and then participants could vote on them. The most prominent guidelines in Germany were “Fair/equal educational opportunities for all” and “Work/performance must always be worthwhile.” In Slovenia, the guidelines with the highest votes were “Change in the taxation system – more tax brackets” and “Improving the link between education and economy.” In both countries, a guideline promoting the introduction of an UBI made it into the final voting and found a relatively high support (30 positive votes in Slovenia, 28 in GermanyFootnote 3). At the end of day 2, the participants were asked to fill in again the same survey-questionnaire as in the beginning of day 1.

Focus groups

The FGs took place in October 2016 (October 10th, 11th and 12th in Germany, and October 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th in Slovenia) in Berlin and Ljubljana. The FGs were carried out by the same research agencies as the DFs, and they took place in professional focus group studios (with one-sided mirrors, audio/video-recording facilities, etc.). Recruitment was also carried out by the research agencies as for the DFS, using common criteria agreed on by the WelfSOC team. Each focus group was supposed to represent a distinct social group regarding status and stage of life: the middle class (determined via income, education and occupation), the working class (ditto), young people (below 35 years of age), retirees (aged 60 years or above) and women with care responsibilities managing work and family life (see list of participants below). The participants received an incentive for their participation (40 € in Germany, 20 € in Slovenia).

In each focus group were eight to nine participants,Footnote 4 and each group lasted around 2 h and followed the same structure in both countries: After an introduction and a brainstorming on “the welfare state” (as in the DFs), the moderator presented six vignettes to the participants. These were (always in the same order and here translated into English):

-

• An unemployed person in good health.

-

• An elderly person in good health; not working anymore.

-

• A family with roughly the median income and two children under 3 years.

-

• A low-income earner with the minimum wage.

-

• A well-off earner.

-

• An immigrant.

The moderators asked the participants what social benefits and services the person(s) on the vignettes should receive and what should be demanded from them – and why. When participants expressed their views, the moderators asked for specifications, and why certain aspects mattered in the eyes of the participants. Each vignette was discussed 15–20 minutes (with the first vignette usually taking a bit longer to make the participants familiar with the format). At the end, the focus groups (FGs) were asked to rank the vignettes in terms of about whom the welfare state should care most/least and to discuss the resultant rank order and justify their ranking decisions.

The UBI was discussed in Slovenia and in Germany only in the middle class group. Given the design of the FGs, the debates were necessarily shorter than in the DFs, but due to the moderation, participants were nevertheless encouraged to justify their views, which provides some interesting insights into their perceptions on the UBI – which is why we include the FG data in our analysis. The fact that in both countries the UBI was only brought up in the middle class groups is in line with the findings form representative studies that show that the UBI is more salient among higher educated people – however, with the small sample in our study, we should not stretch interpretation too far.

List of DF-participants

Slovenia

Germany

List of FG-participants

Slovenia

Germany