Introduction

Digitalisation and increasing automation are expected to have profound impacts on the transformation of work. These processes particularly affect the question of work arrangements. Some jobs will be replaced entirely, others transformed and new kinds of work arrangements will emerge. While large-scale job replacement has not yet been observed, an area where the transformation of work is more visible is the platform economy. Platform companies are digital intermediaries in two- or multi-sided markets that enable a free interaction of supply and demand (Rochet & Tirole, Reference Rochet and Tirole2003). As digital intermediaries, they benefit primarily from network effects, which can be of either a direct or an indirect nature. For this reason, the number of users of a given platform is the most important metric for success and explains the strong focus on expansion, which is generally valued higher than profitability (Kenney et al., Reference Kenney2021).

The employment model of platform companies is highly contested and subject not only to academic, but also to political debates. Platform companies rely on independent contractors referred here to as self-employed gig workers fulfilling tasks rather than jobs in a more or less freelance position. A remuneration model that is oriented towards paying per completed task rather than fixed hourly wages, in particular, represents a departure from previous work arrangements (Behrendt, Nguyen, & Rani, Reference Behrendt, Nguyen and Rani2019). The reason why independent contractors are such a controversially debated topic is that platform companies deliberately misclassify their workers as independent contractors. From a labour law perspective, the thresholds for being an independent contractor (resp., being self-employed) are quite high. Decisive in this context is the question of subordination (ILO, 2020). Only if there is no subordination in the relationship between the company and the worker, the latter is considered self-employed. Platform companies often claim that they do not exert any control on the workers in order to misclassify them as being self-employed. The motivation behind the misclassification is that self-employed workers enjoy fewer rights with regard to wages, working times, work injuries, collective bargaining and in many countries less social protection. In addition, companies in welfare states that are financed by social contributions do not have to contribute to the finance of social insurances (De Stefano et al., Reference De Stefano, Durri, Charalampos and Wouters2021; ILO, 2021a).

The platform economy comes in a variety of forms and includes location-based platforms for ridesharing companies (Uber and Lyft) or food delivery start-ups (Deliveroo, Uber Eats and Foodora), low-paid, microtask platforms (Amazon Mechanical Turk and CrowdFlower) and better-paid, freelance platforms (Upwork; Graham & Woodcock, Reference Graham and Woodcock2018). Even though the platform economy is a relatively new phenomenon and, in most countries, its size does not exceed 1–2 per cent of the adult population, who perform platform work regularly, its potential effects on the organisation of work remain significant. One of the few measures of platform work is the online labour market index developed by the Oxford Internet Institute that tracks the real-time development of tasks and projects posted on the five largest online labour platforms and is therefore a proxy for the development of platform work. Between 2017 and 2021, the index increased by 50 per cent (Online Labour Index, 2020).

As already argued, the question of independent contracting and particularly the misclassification of workers as being self-employed raises a lot of challenges such as pay, collective bargaining, working times or welfare state financing. This paper looks at one particular challenge, which is the integration of these nonstandard forms of employment into existing social protection systems. Independent contractors working for platform companies are, in most cases, low-paid and part of the most vulnerable groups in the labour market (Behrendt & Nguyen, Reference Behrendt and Nguyen2019). Gaps in social protection coverage further exacerbate their situation and pose severe challenges for states to deal with independent contracting, particularly as it is expected to grow. It also raises the overarching question of how well social protection systems are prepared to adequately cover forms of employment that depart from typical full-time, dependent employment relationships.

The aim of this paper is, therefore, twofold. First, to find out how accessible social protection systems are for self-employed workers across major European countries, I developed an index on access to social protection for the self-employed. Second, based on this index, I examined the responses towards platform work in a couple of countries. In particular, I wanted to analyse whether the degree of accessibility to social protection for self-employed workers is a predictor for a given country’s response towards the regulation of platform work.

I intend to show in this paper that those countries, which offer the best access to social protection systems for self-employed workers, tend to develop a more inclusive response by integrating platform work into the industrial relations system via social dialogue. Particularly in the Nordic countries and Austria, which offer almost full access to social protection for the self-employed, current responses to regulate platform work focus on social dialogue and the negotiation of collective agreements. As social protection schemes for platform workers, who are mostly self-employed, are widely accessible, it is less of a pressing policy challenge and platform work is understood to be less antagonistic from a social protection perspective. In contrast, countries such as the Netherlands and Germany, with their limited access to social protection for self-employed workers, have developed a rather confrontational response aimed at challenging the self-employment status of platform workers or extending social protection coverage. The term confrontational does not assess the actions taken by the state, but is merely a description of the fact that the states take actions at all. Contributing to the literature on employment relations systems, this paper therefore sheds light on how well-prepared major capitalist economies are to deal with new forms of employment and where differences in their responses to platform work can be identified.

The rest of this article is organised as follows: the first section includes a literature review on platform work. It focuses on the size of the platform economy and different typologies to better grasp the phenomenon. Moreover, the existing literature on social protection systems and platform work is briefly discussed and research gaps are identified. In the second section, the research questions and hypotheses are discussed. The third section presents an overview of estimates of platform work across major Western European countries and introduces an index on the accessibility of social protection systems for platform workers. In the following section, some of the responses for regulating platform work across countries are highlighted. Finally, the results are critically discussed and avenues for further research are stressed.

Literature review on platform work

The emergence of platform work is attributed to the growth of digital tools and a greater demand for flexibility, mostly on the part of the employer. Instead of being regular employees, workers in the platform economy are mostly self-employed and move as independent contractors from one gig to another (Stanford, Reference Stanford2017). This form of nonstandard work stands in stark contrast to the stable, long-term employment relationships that shaped many mature capitalist economies over the last few decades. In the context of platform work, the distinction is mainly made between gig, crowd and cloud work. Gig work refers to piecemeal, location-based work, ie., individuals are paid for specific tasks rather than being hired for a job. If a task is not assigned to a specific individual and does not have to be fulfilled at a specific location and time, but rather is offered to an otherwise undefined crowd, the literature refers to crowd work. Finally, cloud work includes all platform-related work that is only web-based (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2017).

Recent research primarily investigated the employment conditions of platform work. According to several studies, platform work is often associated with low wages, long working hours and high stress (Forde et al., Reference Forde2017; Huws et al., Reference Huws2017). Platform workers tend to be younger, rather higher educated, and are concentrated in urban areas. Thus, platform work affects primarily cities and does not play a big role in rural areas (De Groen et al., Reference De Groen, Kilhoffer, Lenaerts and Mandl2018). Only a minority relies on platform work as a main job, whereas the majority of platform workers use this kind of employment as an opportunity to earn a supplementary income. In this context, Hall and Krueger (Reference Hall and Krueger2018) argued, in a case study on Uber, for instance, that drivers work considerably fewer hours a week than taxi drivers and are primarily attracted to the job because of its promised flexibility. The importance of flexibility as a main determinant to pursue platform work is also emphasised in several other publications (Huws et al., Reference Huws2017; Riso, Reference Riso2019).

A key question for comparative political economy research is the compatibility of existing social protection systems with these new forms of employment relationships. Most social protection systems are designed to protect full-time, standard employment contracts, whereas significant gaps exist in the protection of all nonstandard employment relationships such as self-employment, temporary work or part-time work (Forde et al., Reference Forde2017). The ILO (2019) analysed in several studies, for instance, the largest protection gaps for these forms of employment that exist across different social protection systems. They found significant coverage gaps for nonstandard forms of employment, particularly in contribution-based social protection systems, often with regard to pensions and unemployment benefits. Jerg et al. (Reference Jerg2021) reviewed the compatibility of social protection systems with the needs of so-called multiple jobholders in Denmark, the United Kingdom and Germany and identified substantial coverage gaps. Opening social insurance schemes, particularly for self-employed workers, is understood as a way to close gaps in social protection (Behrendt & Nguyen, Reference Behrendt and Nguyen2019). However, most of these studies provide a rather general analysis of social protection or look at specific types of new employment forms that indirectly include platform workers (Forde et al., Reference Forde2017; Joyce et al., Reference Joyce2019). Similarly, partly due to the very recent nature of the platform economy, there is not yet much comparative research into how countries respond to the challenge of regulating platform work apart from case studies on single companies such as Uber. Nor is there comparative research on the link between access to social protection systems and responses towards platform work. For these reasons, this study investigates the following research questions:

RQ1: How accessible are social protection systems for platform workers across countries?

Platform work arrangements, which are, in most cases, based on self-employment, depart from the standard, full-time employment relationships and therefore pose a particular challenge for many European social protection systems. Even though some convergence, regarding the social protection of dependent and independent employment relationships, has been achieved over the past 20 years across European countries, important differences remain (Spasova et al., Reference Spasova2019). I analyse to what extent social protection systems offer access to self-employed workers. In particular, I look at specific social protection schemes and evaluate to what extent access to self-employed workers is provided. The different degrees of accessibility are translated into an index, which shows different degrees of access, ranging from full to no coverage. Criteria for the different degrees of accessibility are conditionality, duration of benefit payments or differences in coverage between groups of self-employed workers.

RQ2: Which responses are formulated by countries to regulate platform work?

Platform work is a relatively new regulatory challenge, which explains why only comparatively few countries have already developed a response on how to regulate platform work. At the core of the regulatory debate lies the question of how better social protection for platform workers can be achieved. In order to achieve that goal, I hypothesise that countries can either (1) pursue a more integrative response, aiming to integrate platform work into the respective industrial relations system or (2) follow a more confrontational approach to attain better social protection for platform workers. Even though these regulatory responses are not mutually exclusive, I expect certain preferences across those countries that have started to formulate a response towards platform work. Countries with wide accessibility of their social protection systems for self-employed workers are expected to integrate platform work into their industrial relations system by social dialogue and collective agreements because platform work is a less pressing policy challenge. In contrast, I expect countries that have only limited accessibility to their social protection systems to follow a more confrontational response, particularly aimed at reclassifying platform workers as employees, to circumvent gaps in social protection coverage.

Methodology

The analysis follows a comparative case study design and relies on an extensive body of data and academic publications as well as grey literature. Countries covered in this study include ten major European countries: Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and the United Kingdom. This selection is justified by the intention to obtain a comparable case study design that allows some variations between countries. These countries vary considerably, not just with regard to the type of welfare state, but also with respect to the market economy they represent.

For the purpose of creating an index on the access to social protection systems for self-employed workers, the accessibility of nine major social protection schemes in each country has been assessed. This analysis was partly based on the MISSOC database, the European Network of Social Policy thematic reports on access to social protection and accompanied by own research into the specific social protection schemes (MISSOC, 2020a; Spasova et al., Reference Spasova2017, Reference Spasova2019). To better compare the accessibility of social protection systems across countries, an access to social protection index was constructed, which shows some aggregation of variation between countries. Finally, the analysis of country responses to platform work was based on an extensive literature review of academic papers, government publications, assessments of international organisations and newspaper articles.

Size of the platform economy

Obtaining estimates of the size of the platform economy is helpful to grasp the relative importance of platform work arrangements and how it compares to the media attention they receive. However, estimates of the level of platform work are subject to great uncertainties. A major problem is that this form of employment is not yet covered in official labour market statistics. Moreover, there is great variety in how platform work is defined, which further contributes to the uncertainty of the estimates (Katz & Kruger, Reference Katz and Kruger2019; Riso, Reference Riso2019). This also explains why estimates on the size of the platform economy often differ greatly depending on the source. Most of these studies are based on surveys and differentiate between platform work as a main or second job. The number of people working in the platform economy occasionally exceeds those who rely on platform work for at least half of their income by a great margin. This result underlines the fact that platform work has not yet been established as an employment relationship that replaces standard employment on a larger scale. In most countries, 1–2 per cent of the adult population earns at least half of their income via platform work arrangements.

Despite the relatively small size of the platform economy, this issue is still of great importance for several reasons. First, platform companies are growing at an unprecedented rate and are now among the most valued companies in the world. Whereas in 2000, only one of the ten most valuable companies in terms of market capitalisation was considered a platform company, today seven platform companies are among the most valuable companies (Kenney & Zysman, Reference Kenney and Zysman2016). Second, platform work is growing at a fast rate. For instance, the online labour market index, which measures online platform work, increased between 2017 and 2021 by 50 per cent. Platform work is expected to further increase, particularly due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which has increased the demand for online shopping or food delivery services. Third, many platform work occupations are primarily affecting the service sector and are difficult to automate. For instance, last mile activities of logistics and food delivery platforms are expected to be carried out by manual labour in the foreseeable future (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer2021). In a similar vein, despite increasing hype about automated driving systems, this technology has yet to materialise, as ridesharing companies are still exclusively relying on drivers. Fourth, platform work is not entirely new but rather represents a further deterioration of standard employment relationships. Starting in the 1980s, increased outsourcing and subcontracting, also known as the fissuring of work, disrupted standard employment relationships and shifted the focus from careers to jobs as the prevailing labour pattern (Kirchner & Schüßler, Reference Kirchner and Schüßler2020; Weil, Reference Weil2014). A further fragmentation of labour into tasks is thus the latest stage of a process, which has been taking place for a considerably longer time.

Access to social protection for the self-employed

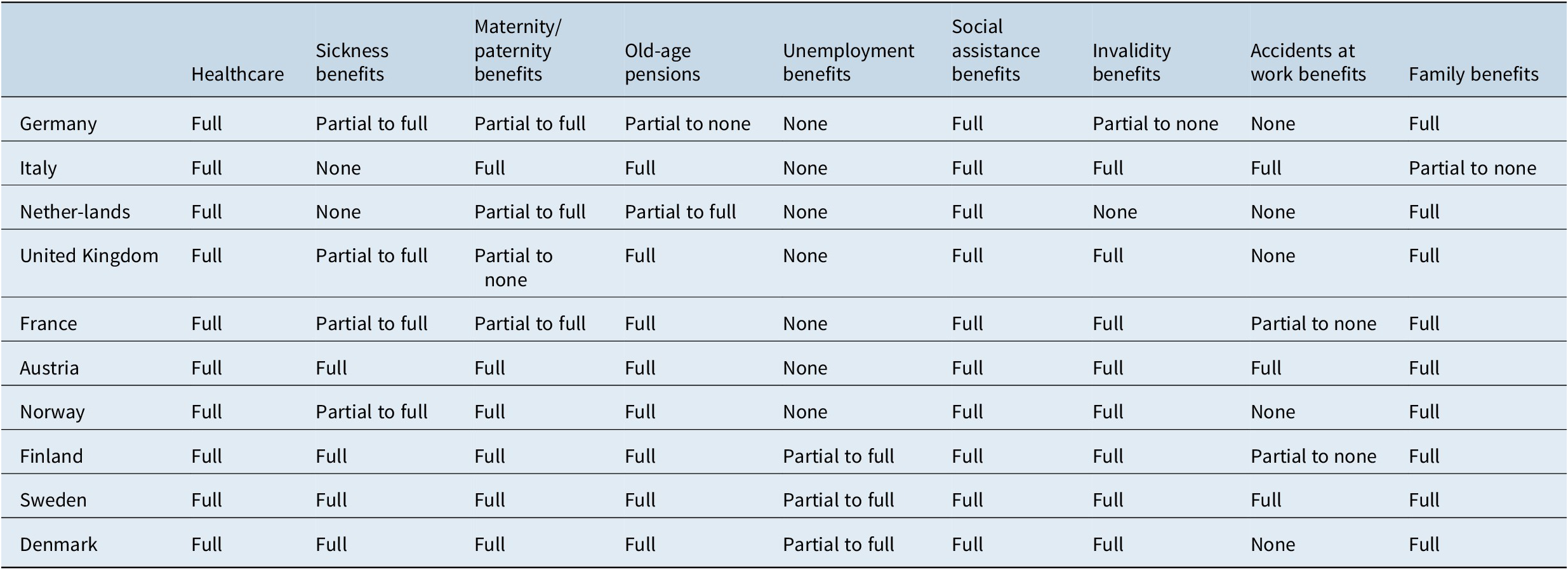

A particular challenge in identifying the most accessible social protection systems for self-employed workers is the comparability of these systems. In order to allow a structured comparison of social protection systems across countries, I have constructed an index which distinguishes between four degrees of accessibility to social protection. In the context of this paper, 1 denotes full accessibility to social protection systems for self-employed workers, whereas 0 denotes the absence of any accessibility. More specifically, I class the accessibility of social protection systems for self-employed workers as either full (1), partial to full (0.66), partial to none (0.33) or none (0).

In classifying social protections systems, I follow the approach by Spasova et al. (Reference Spasova2019), who distinguished between the following nine social protection schemes: (1) healthcare, (2) sickness, (3) maternity/paternity benefits, (4) old-age pensions, (5) unemployment benefits (6) social assistance, (7) invalidity, (8) accidents at work and (9) family benefits. To each of these social protection schemes, I assigned one of the four index values (see Table 1). These scores were added together then divided by the number of social protection schemes in order to obtain an index value between 1 and 0. The allocation of these scores was partly driven by several country reports provided by the European Social Policy Network and the MISSOC database, which was updated, in some cases altered, and accompanied by original research into the respective social protection schemes (see Table 2). Criteria to evaluate the degree of accessibility are as follows: compulsory and denied coverage, tighter eligibility conditions, shorter duration of benefit payments and fragmented coverage among groups of self-employed workers. The example of access to maternity/paternity benefits illustrates the underlying reasoning for the assignment of index scores.

Table 1. Index scores.

Note: Source: Own graph.

Table 2. Classification of accessibility of social protection schemes for self-employed workers.

In France, the self-employed have access to daily maternity benefits of up to €56 per day, which is lower than the €90 per day that employees receive and is therefore classified as partial to full (MISSOC, 2020b). In the United Kingdom, the self-employed have access to a maternity allowance, which is capped at £150 a week if full national insurance contributions have been paid, but do not have access to statutory maternity pay, which offers much more comprehensive protection (Bradshaw & Bennett, Reference Bradshaw and Bennett2017). Due to these differences, maternity/paternity benefits in France are categorised as partial to full and in the United Kingdom partial to none.

The resulting index values, however, only indicate the degree of formal access for self-employed workers to the respective social protection systems. It does not allow an inference regarding the generosity of social protection schemes. For the purpose of parsimony, all social protection schemes are weighted equally, which is arguably a simplistic assumption considering that some social protection schemes, such as healthcare or old-age pensions, are usually considered more important than invalidity benefits for instance. Independent of a causal mechanism, there is a correlation between access to social protection systems and the level of social benefits, as countries with strong access, such as the Nordic Countries, are also those offering the highest level of social protection (Pedersen & Kuhnle, Reference Pedersen, Kuhnle and Knutsen2017).

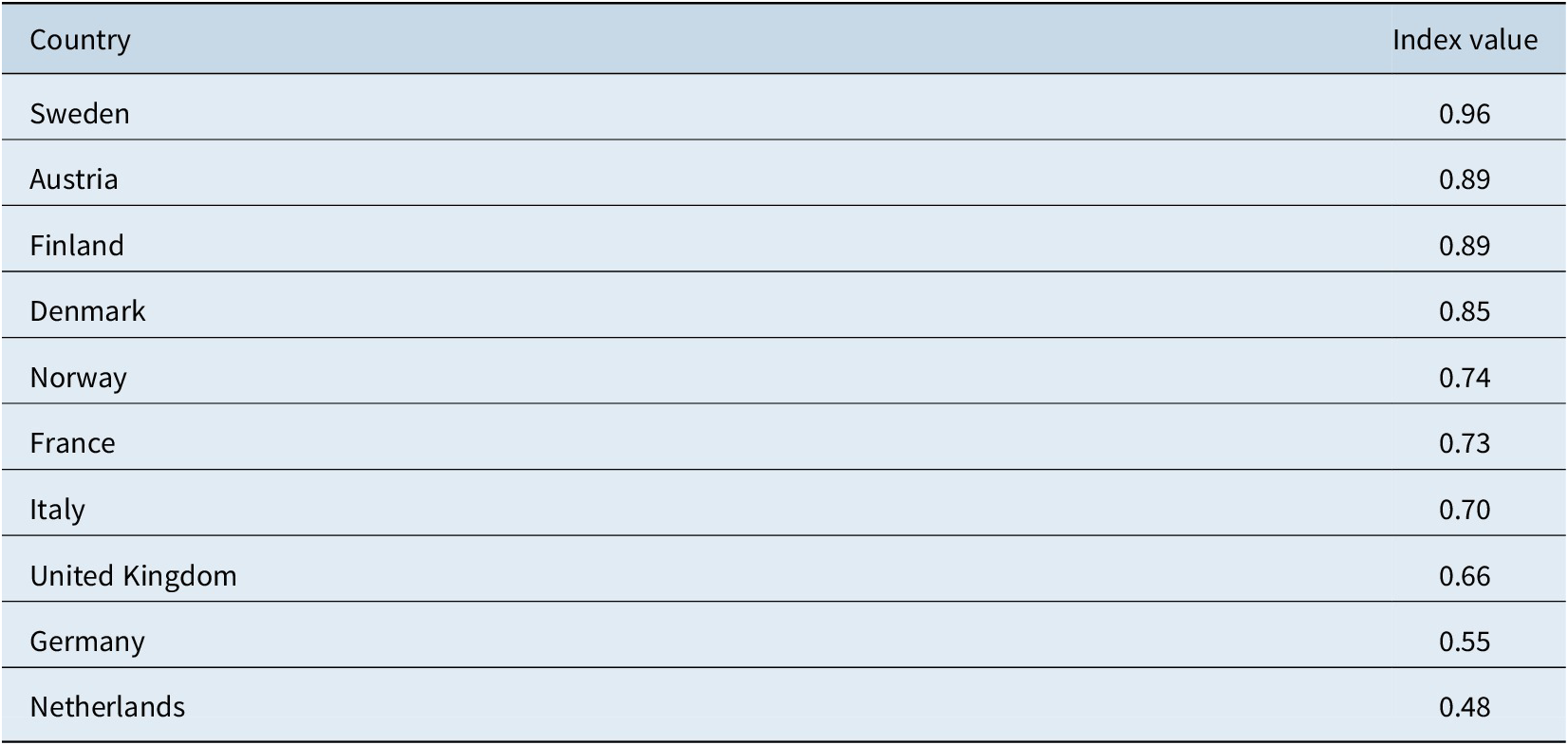

Access to social protection index

Table 2 shows the classification of the different social protection schemes according to the four accessibility criteria: (1) full, (2) partial to full, (3) partial to none and (4) none. The index values for the accessibility of social protection systems for self-employed workers across countries are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Index on the accessibility of social protection systems for self-employed workers.

Note: Source: Own graph.

Sweden has the highest value and provides almost full access to social protection for self-employed workers. Except for access to unemployment benefits, Austria provides the same accessibility to social protection for the self-employed, which is the result of a continuing effort to integrate them into the social security system, starting in the mid-1990s (Fink, Reference Fink2017). In Finland, access to social protection for the self-employed is with the exception of accidents at work benefits quite comprehensive. Surprising at the first sight is the lower value of Norway (0.74), which stands in contrast to the other Scandinavian countries and is explained by the limited access to sickness benefits and no accessibility to unemployment benefits and accident at work benefits. A possible explanation could be that self-employment is a particularly marginal phenomenon in Norway (Jesnes & Oppegaard, Reference Jesnes and Oppegaard2020). In 2018, self-employment comprised only 6.5 per cent of total employment, representing the lowest value among all considered countries. Moreover, most platform workers, such as food delivery riders or drivers of ridesharing platforms, are employed on marginal, part-time contracts instead of being self-employed (Jesnes & Oppegaard, Reference Jesnes and Oppegaard2020).

Italy, France and the United Kingdom provide fairly comprehensive accessibility to social protection schemes for self-employed workers. Coverage gaps primarily concern sickness, maternity/paternity and accident at work benefits. A distinct characteristic of France and Italy is that access to social protection is very fragmented among self-employed workers. Despite some convergence in the last few years, these countries are still characterised by a variety of social protection schemes for special groups of the self-employed (MISSOC, 2020b). The greatest coverage gaps are in Germany and the Netherlands, which have a value of 0.55 and 0.48, respectively. In both countries, access to different pension schemes, maternity/paternity allowances and sickness benefits is considerably more difficult for the self-employed than for regularly employed workers. Moreover, the system is very fragmented, with special rules and access to coverage in Germany for some groups of self-employed workers, such as artists (MISSOC, 2020c). In contrast to other continental European countries, such as France and Italy, there has not been much convergence over the last few decades in providing access to social protection for self-employed workers.

Responses of countries to regulate platform work

Due to the different institutional settings and political alliances, increased social protection for platform workers can be achieved in a number of ways. In the following, I have analysed the responses by countries to the regulation of platform work. Responses refer in this context to all court cases and legislation explicitly dedicated to platform work as well as to collective agreements. These include only court cases and legislation with regard to employment issues, such as employment status classifications and questions of social protection coverage. Court cases and legislation on taxi-related issues, such as the question as to whether Uber provides a taxi service or must be classified differently, are excluded from the study. There is, however, a larger body of literature, especially focused on responses to the expansion of Uber in European countries and the United States (Thelen, Reference Thelen2018).

A central question in this context is which mechanisms explain a country’s regulatory response to platform work. While they are not mutually exclusive, four distinct mechanisms are conceivable. First, there is an emerging body of literature pointing towards the strength of labour movements and social mobilisation as a factor that pressures countries to regulate platform work (Chesta, Zamponi, & Caciagli, Reference Chesta, Zamponi and Caciagli2019; Johnston & Land-Kazlauskas, Reference Johnston and Land-Kazlauskas2018). Second, a well-functioning corporatist system including strong social dialogue could predict whether countries’ responses to regulate platform work are more integrative or more confrontational. The third mechanism involves general labour market conditions. In countries where platform work is only a marginal phenomenon, either because the dissemination of platform companies is low or because there are enough better-paid job openings, its regulation may be a neglected policy issue. Finally, as argued in this paper, the structure of social benefits could explain how a country regulates platform work.Footnote 1 If accessibility to social protection systems is already comparatively broad, social protection of self-employees could be less of a policy challenge, making countries less inclined to intervene. Although this paper primarily provides evidence for the structure of social benefits mechanism, these four mechanisms are not mutually exclusive but rather mutually reinforcing.

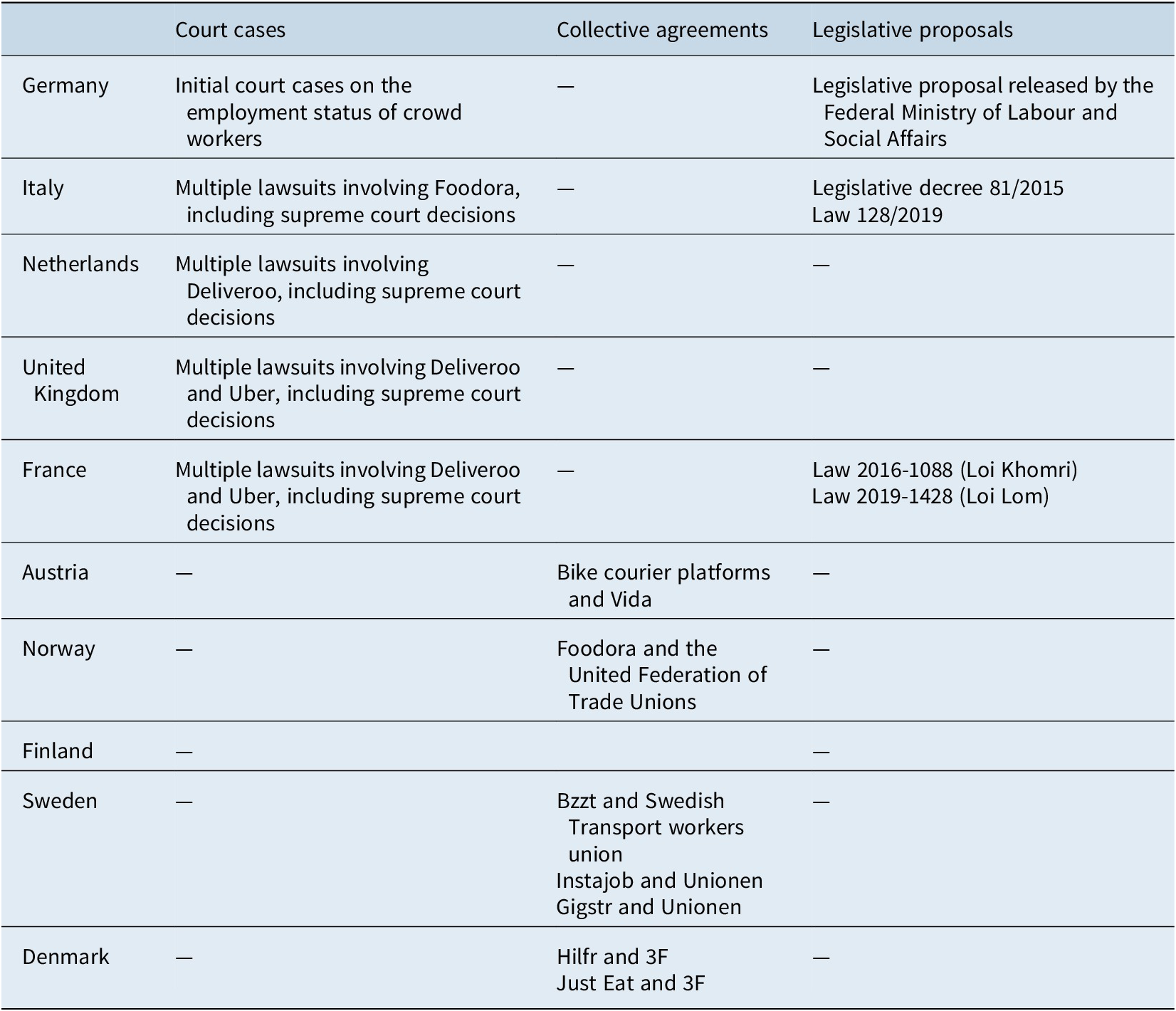

The identified responses – shown in Table 4 – are roughly divided into (1) an inclusive approach aimed at integrating platform work into the respective industrial relations model via social dialogue and (2) a confrontational approach to attain better social protection for platform workers by challenging their self-employment status. The analysis is based on an extensive literature review of academic papers, government publications, assessments of international organisations and newspaper articles. The identified responses are, however, not mutually exclusive, but can rather be pursued in parallel. This clustering is, therefore, a rather rough estimator of the current responses, which, however, can be subject to change in the future. Moreover, the analysis covers only a couple of countries – namely Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Austria, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy – as platform work is a rather new phenomenon and only a few countries have started to take action.

Table 4. Responses towards platform work.

Integration of platform work into the industrial relations system via social dialogue

Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway and Austria are identified as those countries with a more integrative response for regulating platform work from an employments rights perspective. In the Nordic countries and Austria, there have been no court cases on the reclassification of platform workers as employees (Westregård, Reference Westregård2020). Instead almost all court cases in these countries have been on personal transport services and have primarily dealt with the question as to whether Uber represents a taxi service and is, thus, subject to taxi legislation or must be classified differently. So far, the governments in these countries have refrained from adopting legislation targeting employment-related issues of platform work, but have actively encouraged social dialogue among social partners, which plays a key role in the respective industrial relations systems. First attempts have been made to integrate platform companies into the social partnership model (Jesnes & Oppegaard, Reference Jesnes and Oppegaard2020).

In Denmark, trade unions directly negotiated a collective agreement with the cleaning platform Hilfr. Apart from receiving higher wages and social benefits, such as additional sickness benefits and further pension contributions, the platform workers could decide whether to receive an employee status or to continue to work as self-employed workers (Ilsøe, Reference Ilsøe2020). In addition, the Danish trade union 3F negotiated a sectoral agreement with the employer association Dansk Erhverv, which guaranteed riders of the food delivery platform Just Eat higher pay and additional benefits, such as overtime pay (Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2021).

Although there are no negotiated collective agreements exclusively targeting platform workers in Sweden, the scope of existing collective agreements has been extended. This was, for instance, the case with personal transport platform Bzzt, which, unlike most platform companies, hires its workers on marginal, part-time contracts. An agreement between the Swedish transport union and Bzzt extended the collective agreement of the taxi sector and guaranteed the platform drivers the same standards as those taxi drivers already covered by the agreement (Jesnes et al., Reference Jesnes2019).

Responses in Finland towards platform work are less distinct. Even though the Finnish government showed an interest in platform work, there have not been any legislative proposals in addition to a complete absence of court cases on the employment status of platform workers. Instead, platform work is rather discussed in the context of improving social protection for the self-employed, which is, however, already on a comparatively high level. This includes establishing a combined unemployment insurance for employees and the self-employed, a policy proposal that has been discussed often over the last few years, though with little process (Mattila, Reference Mattila2020).

In Norway, a collective agreement with the food delivery company Foodora was negotiated, which grants riders higher wages and an early retirement provision (Ilsøe, Reference Ilsøe2020). The fact that it is even possible to engage in collective agreements sets the Nordic countries apart from other European countries, where platform companies have a much more hostile attitude towards social dialogue and can be seen as a cautious indication of the resilience of the Nordic model. A major difference between Denmark and Sweden, on the one hand, and Norway and Finland, on the other, which could provoke legislative intervention in the future, concerns the question of collective agreement coverage. In Denmark and Sweden, collective agreements are characterised by a voluntarist nature, whereas in Norway and Finland, legal extension mechanisms exist to extend their coverage to companies, which did not sign any agreements (Jesnes & Oppegaard, Reference Jesnes and Oppegaard2020). If platform companies were less willing to voluntarily negotiate collective agreements in the future, the government could start to intervene.

Also in Austria, where access to social protection schemes between employees and the self-employed have converged considerably over the last few decades, conflicts in the response to platform work tend to focus on social dialogue. While there are hardly any court cases and legislative proposals targeting platform work, responses included the desire to establish work councils within platform companies and extend the scope of collective agreements to cover platform work. In 2019, the first worldwide collective agreement between a bike courier platform and a trade union was concluded. This agreement regulated working time and resting periods, introduced a minimum wage and increased paid leave entitlement (Widner, Reference Widner2019). A common characteristic between the Nordic countries and Austria is the extensive social protection coverage of self-employed workers (De Groen et al., Reference De Groen, Kilhoffer, Lenaerts and Mandl2018). As accessibility to social protection is less of an issue in these countries, governments appear to be less inclined to intervene and encourage conflict resolution via the social partnership model, which governs industrial relations (De Groen et al., Reference De Groen, Kilhoffer, Lenaerts and Mandl2018).

Confrontational responses to platform work, aimed at challenging the self-employment status of platform workers

In France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Italy and Germany, the response to platform work is more confrontational. Primarily driven by an increasing number of court cases, the classification of platform workers as being self-employed became a major point of contestation. The primary legal question, when deciding on the employment status of platform workers, is the question of subordination (Aloisi & De Stefano, Reference Aloisi and De Stefano2020). Only when it is proven that workers are impeded in organising their own activity freely and are under substantial control by their employer are they deemed employees. The employment status classification of workers thus depends on how narrow or broad a definition is given to subordination. In France, the social chamber of the French supreme court showed a broad understanding of subordination and, in 2018 and 2020, decided that food delivery riders of the platform Take Eat Easy and Uber drivers have to be reclassified as employees, as the platforms allegedly exert a substantial degree of control on their workers, for instance, by controlling work performance via a rating system (Palli, Reference Palli2020). France is also one of the very few countries that adopted legislation explicitly targeting platform work in 2016. A key element of the loi Khomri in 2016 was the extension of the right to collective bargaining, freedom of association and collective action to platform workers (Daugareilh et al., Reference Daugareilh, Degryse and Pochet2019). However, the employment status and social protection of platform work still remains a very controversial topic in France. Even though some improvements have been made, such as an extension of accident at work insurance to some self-employed workers, the social protection system is still very fragmented with separate schemes for the self-employed, who pay comparatively high contributions in relation to the benefits they receive (Palli, Reference Palli2020).

In the United Kingdom, conflicts about the employment status of platform workers dominate the debate. A major difference lies, however, in the interpretation of the subordination principle, which is understood more narrowly. Whereas food delivery riders were ruled to be self-employed, as they are allowed to let third parties carry out their shifts and, thus, are ruled not to be subordinated by their employer, the courts decided differently in the case of Uber. In 2021, the Supreme Court decided, in its last ruling, that Uber drivers are workers,Footnote 2 which gives them access to the minimum wage and holiday payments (Butler, Reference Butler2021). Employment conditions of the self-employed and other nonstandard employment are discussed in a wider context. Initiated by the Conservative government, the Taylor review was published in 2017, which contained an analysis and recommendations on the regulation of the future of work (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor2017). These recommendations included proposals to reform employment law and to strengthen the social protection of self-employed workers. Despite promises by the incoming Johnson government to implement some of these recommendations, employment reforms have been postponed, which leaves the regulation of platform work, at least for the moment, to the courts (Partington, Reference Partington2021).

Similar to the aforementioned countries, in the Netherlands, the distinction between employment and self-employment is increasingly becoming a point of contestation. The food delivery platform Deliveroo especially is involved in a series of lawsuits. After ruling against the reclassification of a rider as an employee, the same court ruled, in 2019, that Deliveroo couriers should be classified as employees. The latest development on this matter occurred in 2021, when the Amsterdam Court of Appeal confirmed earlier rulings that Deliveroo couriers are employees. In two similar cases brought forward by the trade union FNV and the road sectoral pension fund, the courts ruled that Deliveroo is not a technology platform but a delivery service firm and, hence, required to pay pension premiums to its staff with employment contracts (SIA, 2019).

In Italy, the response to platform work is also confrontational, but is pursued from a slightly different angle. Instead of reclassifying platform workers as employees, social protection was extended to them. Full social protection was extended to a subset of workers whose work is organised by another party, so-called etero-organizzazione or organisationally dependent, self-employed workers (Aloisi, Reference Aloisi2020). Criteria for being subsumed under this class of workers are, for instance, that the employer dictates the location and time when a specific task has to be fulfilled. In several court rulings, food delivery platform workers were classified as organisationally dependent, self-employed workers and their social protection coverage, such as access to sickness benefits, was extended. Therefore, they enjoy similar social protection to regular employees (Aloisi, Reference Aloisi2020).

The employment status question is also becoming increasingly more important in Germany, where in 2020, the highest labour court ruled that crowd work is, under certain conditions, dependent employment (Lutz, Reference Lutz2020). The reclassification of platform workers as employees is also a central component in a legislative proposal by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs in Germany. This legislative proposal, specifically targeting platform work, aims to reverse the burden of proof for the reclassification of employees. If platform workers present evidence indicating the existence of an employment status, the platform provider has to prove that this is not the case. Moreover, the legislative proposal intends to increase the social protection of self-employed platform workers by integrating platform companies into the statutory pension insurance and accident insurance schemes (Denkfabrik, 2020).

Even though there are considerable variations in courts’ decisions on the employment status of platform workers, the fact that so many cases are being brought to court can be seen as an indication of the limited assertiveness of social dialogue. Instead, platform work appears to be regulated by court rulings until governments pass new laws, as there have hardly been any collective agreements between social partners. First legislative proposals, particularly in France and Italy, have been adopted that directly target platform work, by improving the social protection of self-employed workers and are, thus, a reflection of a rather confrontational response towards the regulation of platform work.

Conclusion

Platform work, although still a small but rising phenomenon, represents a mounting challenge for countries. This challenge arises from the fact that the employment status of platform workers is atypical and often deliberately misclassified, which has a number of repercussions. Among these repercussions are wage levels, working times, work injuries or competition distortion of companies (ILO, 2021b). This article focused on one of the challenges, namely social protection coverage. Particularly in countries whose social protection systems are oriented towards the full-time, standard employment contract, integrating platform work relationships into existing social protection schemes can be a significant obstacle. These challenges are reflected in an increasing number of court cases, legislative proposals and collective agreements regarding platform work.

This paper analysed the relationship between the degree of access to social protection schemes for self-employed workers and the responses towards platform work across ten major European countries. The aim of the paper was twofold: first, an index of access to social protection for self-employed workers was constructed for the countries covered in this study. Second, the responses of these countries towards the regulation of platform work have been identified and an analysis undertaken as to whether the degree of accessibility to social protection for self-employed workers is a predictor for a given country’s response towards the regulation of platform work. In the Nordic countries and Austria, where self-employed workers enjoy almost the same access to social protection as regular employees, the response towards platform work appears to be more integrative. There are hardly any court cases on the classification of platform workers as employees, and governments are still refraining from intervening too much into the regulation of platform work. These countries are also the countries covered in this study that successfully negotiated collective agreements with platform companies, which is an indicator for a more integrative response by incorporating platform work into the respective industrial relations system via social dialogue.

A possible mechanism that explains a country’s response towards platform work is the structure of social benefits. In those countries with wide accessibility to their social protection systems, social protection for self-employees is less of a policy challenge as the baseline protection level is relatively high. This high degree of access to social protection enables a more integrative response towards platform work, as platform companies and their preferred employment model are less threatening from a social protection perspective. Points of contestation with platform work primarily concern other topics, including taxes and sector-specific regulations, such as taxi legislation.

In countries with less accessibility to their social protection system, a rising number of court cases on the employment status classification and legislative proposals can be observed. These responses are an indicator of a more confrontational approach towards the regulation of platform work and could be explained by the fact that social protection for (self-employed) platform workers is a much more pressing policy challenge. Platform work, in that sense, is understood to be more antagonistic from a social protection perspective.

The evidence, presented in this paper, for a link between access to social protection and response towards platform work is, however, preliminary and tentative. A greater country sample including countries such as Portugal or Spain and more in-depth studies are required to obtain a better understanding of platform regulation. Moreover, the presented classification of social protection systems leaves room for debate. Whereas the categorisation of the Nordic countries and Austria is quite robust, as access to social protection for standard employment and self-employment is relatively uniform in both countries, either through welfare state universalism or reforms targeting self-employed workers, the situation is more complex in the remaining countries. In France or Italy, for instance, access to social protection between regular employees and the self-employed has converged in the last few years. However, the social protection system in both countries is still very fragmented with a variety of social insurance schemes targeting different groups of self-employed workers. Norway with much greater universalism and these two countries provide nearly the same level of access to social protection, but differ significantly in their responses. While this paper shed light on the structure of social benefits as an explanation for how countries react to platform work, there are also other possible mechanisms. For this reason, there are three possible avenues for future research on the effect of: (1) the strength of the labour movement and social mobilisation, (2) a well-functioning corporatist system and social dialogue and (3) general labour market conditions as explanatory factors for countries’ regulatory responses to platform work.

Funding

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the reserach, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Grant by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Germany, No. DKI.00.00003.19.