Introduction

A primary goal of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is to advance the science of community engagement in research [1]. To date, the biomedical literature is limited and mixed on the impact of engaging stakeholders in research, but there is sufficient evidence to suggest that stakeholder engagement is indeed a promising strategy to making research findings more meaningful to patients and the providers who care for them and, as a consequence, more likely to be used and to benefit citizens [Reference Domecq2–Reference Mann, Chilcott, Plumb, Brooks and Man8].

Clinicians, social scientists, and funders have demonstrated increased interest in how to effectively involve stakeholders in all phases of research so that research is relevant, meaningful, and actionable to those receiving the intervention, delivering the intervention, and translating the model into standard practice and policy. Initially, much of the research focused on patient and public involvement in the early stages (i.e., design and implementation), including projects focused broadly on the patient experience, or narrowly on specific population groups or specific areas of research [Reference Concannon9–Reference Goldstein, Farquhar, Crofton, Darby and Garfinkel13]. More recently, several journal articles describe frameworks for how to integrate patient and family advisors in all phases of the research process and include specifics of how to share decision-making between researchers and other stakeholders [Reference Fagan, Morrison, Wong, Carnie and Gabbai-Saldate14–Reference Dudley16]. Others describe the training and competencies of researchers required for effective stakeholder engagement [Reference Dudley16, Reference Frisch17]. A review of stakeholder engagement highlighted that the evidence of impact was weak due to inconsistent data and lack of detail [Reference Brett3]. Studies to date emphasize the importance of evaluating the process of involving patients and the public in all phases of research and the need for evidence of how stakeholders’ perspectives can be meaningfully synthesized and used to shape research design, implementation, and dissemination [Reference Brett3, Reference Blackburn10, Reference Boivin18–Reference Wilson20].

This paper describes how stakeholders contributed to the design, conduct, and dissemination of findings of a multicenter pragmatic clinical trial and the changes the academic team made to the study in response to their input. The cluster-randomized COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) Study investigated the effectiveness of implementing an evidence-based, comprehensive, post-acute stroke transitional care model compared with hospitals’ usual care. The study design and methods – including methods used to engage stakeholders – are published [Reference Gesell21–Reference Duncan23]. This paper describes how stakeholders shaped this multicenter pragmatic trial.

Materials and Methods

COMPASS Study

The COMPASS Study was a pragmatic cluster-randomized controlled trial conducted in 40 hospitals with approximately 10,000 stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) patients in North Carolina. Intervention hospitals employed a novel transitional care model, as well as an additional set of billing codes to provide financial incentives, in order to change provider behavior and increase quality of care and recovery outcomes for stroke and TIA patients. The study provided small supplemental funding to hospitals to offset research-related costs only. The primary trial results are published [Reference Duncan23].

The COMPASS model was initially developed in collaboration with the Wake Forest Baptist Health Comprehensive Stroke Center clinical team. It incorporated their prior experience with stroke transitional care through the TRAnsition Coaching for Stroke (TRACS) Program and evidence from the most current scientific literature [Reference Condon, Lycan, Duncan and Bushnell24].

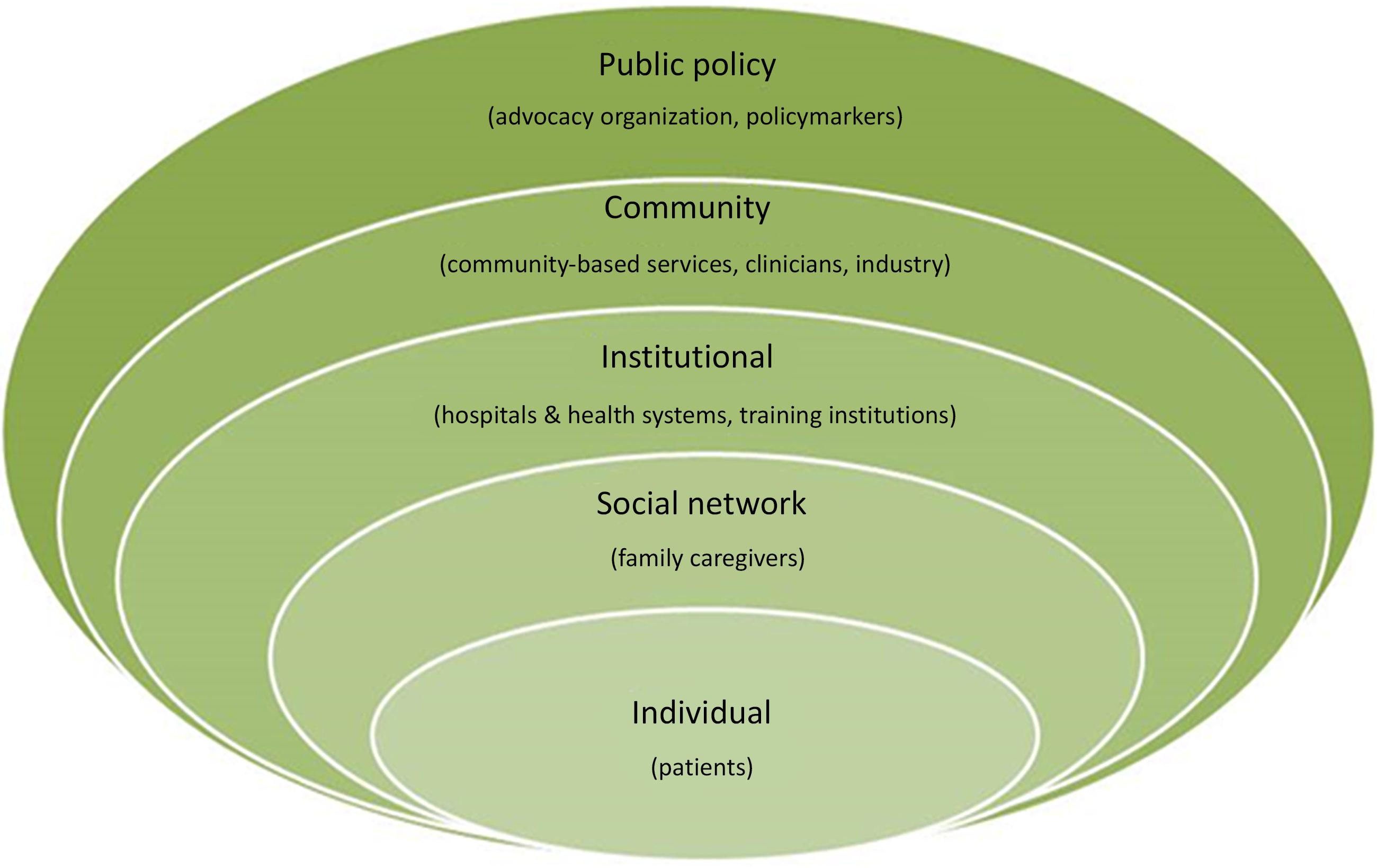

Details on the COMPASS Study’s non-traditional research partners and the rationale for their inclusion have been published [Reference Gesell21]. Briefly, the study team included members from a wide range of stakeholder groups, representing all socio-ecologic spheres of influence on patient health, including: patients, caregivers, clinicians, community-based health and social services, hospitals and health systems, industry partners, advocacy organizations, payers, and policymakers (Fig. 1 ). Our primary goal for stakeholder engagement in the COMPASS Study was to be responsive to both patient and caregiver needs, to treat recovery from stroke as a chronic condition, to create a realistic workflow for hospital-based providers, and to link patients to community-based services to address social determinants of health to maximize recovery.

Fig. 1. Stakeholder groups representing all levels of influence on patient health participated in the COMPASS study during design, conduct, and dissemination [Reference Gesell21].

Data Collection

We used qualitative methods to investigate stakeholder needs and priorities, which enabled us to more fully capture insights and reactions than would be possible with quantitative methodologies with pre-defined response options. Qualitative methods also allow new areas of inquiry to emerge and can reveal perspectives that researchers may not be able to foresee [Reference Charmaz25]. Transitional care is a process in which the patient moves from one healthcare setting and set of providers to another. During this transition, providers do not typically understand the next step in the care chain or the barriers patients face; the patient is the only “stable factor” in this process and thus the best source of information. Thus, qualitative methods were ideally suited for our purposes of improving the delivery of transitional care from the patients and multiple providers’ perspectives and within the clinical workflow.

Eliciting and incorporating stakeholder perspectives involved embedding stakeholders into study committees, assembling resource networks, conducting focus groups, and group discussions. These group interactions encouraged stakeholders to talk to one another, ask questions, and comment on one another’s experiences and perspectives, leading to more nuanced recommendations. Furthermore, the iterative process of holding multiple discussions over time with diverse groups of stakeholders helped refine recommendations and confirm that recommendations correctly reflected their ideas and were feasible with existing resources.

We collected input from stakeholders using committees and resource networks, as described below.

Statewide patient and stakeholder engagement committee

At the state level, we formed a large group of partners to be both inclusive and to leverage the tremendous expertise across the state. We purposefully included diverse perspectives, including urban/rural lived experiences of patients and providers, as well as patients and caregivers who represented varied income and educational levels. Some stakeholders on this committee were embedded in the study’s Steering Committee and subcommittees, which met weekly, so that they could have continuous input throughout the study. Some stakeholders were consulted outside the regular meeting schedule, most frequently by the study’s Principal Investigator (PI) and the Director of Implementation, both clinicians with extensive familiarity with North Carolina’s stroke system of care. Other stakeholders provided important insights via focus groups and interviews. See Supplement 1 for an example of what one focus group of elder, rural residents revealed to researchers, how that information was used, and how these stakeholders were informed that we had made changes to the study in response to their feedback.

Community resource networks

At the local level, we guided the post-acute care coordinator at each of the 40 participating hospitals to develop a COMPASS Community Resource Network (CRN). These networks of community-based health and social service providers helped the post-acute care coordinator link patients to resources outside the hospital that could support recovery. The goal was to incorporate local knowledge into the intervention to maximize successful implementation. Each CRN included a representative from aging services, a pharmacist, a home health provider, and a rehabilitation provider. Some CRNs also included a representative from the local health department, a community paramedic, a faith leader, a local stroke survivor, a local caregiver, a transportation service representative, and/or a social worker, reflecting each community’s unique resources and strengths. As part of implementation, each CRN engaged with the study’s Director of Implementation and other implementation and training team members during on-site day-long hospital meetings at the beginning of the study. CRNs also provided feedback to the study team by participating in bi-weekly group conference calls for problem solving. CRNs also participated in two surveys in which they shared challenges they had experienced as well as solutions. These data collection activities allowed the study team to continuously learn from those delivering the intervention.

Consent

All stakeholder engagement activities were submitted to the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB classified (and approved) some stakeholder engagement activities as “Human Subjects Research” and other stakeholder engagement activities as “Not Human Subjects Research.” For IRB-approved research activities (focus groups, interviews, surveys, recorded group conference calls), participants provided verbal consent. For activities that did not meet the IRB definition for research (working group meetings of the study team and stakeholders, day-long meetings to discuss ideas with stakeholders, documentation of decisions made by study team members after discussion of stakeholders’ ideas), there was no consent process.

Data Analysis

Guided by Grounded Theory, we asked stakeholders about their unmet needs, priorities, experiences with, and recommendations for post-acute stroke care. We extracted themes which were discussed as a team and with other stakeholder groups for feasibility. A consensus approach was used [Reference Slaldana26, Reference Israel, Schulz, Parker and Becker27]. Due to resource constraints and the intention of including stakeholder feedback continuously (starting with proposal development and throughout the 5-year study period), the notes from the focus groups, interviews, surveys, and meetings were not tagged with codes. Illustrative stakeholder quotes are included to support selection of themes. Stakeholder ideas that were intentionally incorporated into the study were documented in real time using a tool we developed with the REDCap software system. This tool (Stakeholder Engagement Tracker) is available in the REDCap shared library [Reference Gesell, Halladay, Mettam, Sissine, Staplefoote-Boynton and Duncan28]. Throughout the study, we documented how stakeholders’ ideas and input shaped and refined the study using pre-defined data fields. These data fields were selected from PCORI’s reporting requirements, to document which stakeholders were involved, how, during which phase of the study, what the advice was, and whether it was incorporated. This process allowed us to search the database. Open-ended data fields captured details (see Gesell et al. 2020 for description of tool) [Reference Gesell, Halladay, Mettam, Sissine, Staplefoote-Boynton and Duncan28].

We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting guidelines, the completed checklist for which is available in Supplement 2.

Results

With exception of development of the statistical analysis plan and the conduct of the statistical analyses, all aspects of the study were shaped by inviting and addressing the perspectives of non-traditional research partners. This engagement resulted in important changes to many aspects of post-acute stroke care. In addition, stakeholder input modified training for caregivers who are essential for stroke patients’ recovery, for hospital-based providers who generally lack awareness of what patients deal with after they leave the hospital, and for community-based health and social service providers whose services can support recovery yet often go underutilized because they are not integrated with hospital-based care and are unfamiliar to the patient. Details on the diversity of participating stakeholders, as well as key lessons learned from each group, and the ways that they shaped the study are presented in Table 1. Also described are ways that stakeholders’ engagement with the academic team, in turn, informed changes within partner organizations that extend beyond the scope of the trial.

Table 1. How stakeholders influenced the COMPASS study and the COMPASS study influenced stakeholders (examples)

CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; COMPASS = COMprehensive Post-Acute Care Services Study; IRB = Institutional Review Board; NC = North Carolina; NIH = National Institutes of Health; TCM = Transitional Care Management.

Members of the statewide stakeholder committee added, shaped, and refined intervention components (e.g., the intervention assesses the caregiver’s ability to care for the patient) and all patient- and provider-facing intervention materials (e.g., content, language, tone, layout, timing of delivery to maximize understanding). Examples of these changes are described in more detail in Table 1.

Weekly Steering Committee meetings included a stroke patient, caregiver, hospital neurologist, pharmacist, nurse, rehabilitation therapists, stroke advocacy organization leader, community-based aging agency leader, and stroke and health services researchers. This diverse leadership team provided perspectives that were often different and sometimes even opposing – and resulted in better problem solving and products. For example, Steering Committee members leveraged their diverse networks to design a comprehensive dissemination plan that maximized reach, identified barriers, and used the most effective strategies to ensure timely and effective communication to patients, community leaders, hospital administrators, and policymakers. Based on stakeholder input, the final plan was written in plain language so that it could be understood by all.

Clinicians and senior hospital leadership identified barriers to attendance at protocol-specified follow-up clinic visits and identified ways to improve attendance at this critical visit. They also provided feedback on how to more seamlessly integrate the intervention into clinical workflows to improve institutional buy-in. In turn, this engagement resulted in dissemination of the COMPASS model in part or in whole to 147 hospitals and rehabilitation agencies beyond the trial sites, with 110 sustaining use. As one stroke coordinator shared with us,

“We had to learn the process of ordering things in the outpatient world instead of the inpatient world… it took us a long time to sort of get over some of those hurdles… in a year, we have actually transitioned I think because the practice and our administrators saw how wonderful this program was and how much we were helping our patients. They actually said “Wow!” … and they said, “we can give you one of ours [nurse practitioners] for half a day now.”

Additional examples of specific stakeholder input and feedback that we elicited through engagement during proposal development and how we modified the intervention and implementation strategies as a result are presented in Supplement 3. For example, patient and caregiver stakeholders shared ways that COMPASS providers could improve their communication with patients, such as repeating instructions and the reasons that certain recommendations were being made to increase adherence. As one patient stated:

“It was also important for the doctors and the therapists to explain it multiple times – not to assume I knew why I needed this.”

Also during proposal development, feedback from hospital-based clinicians alerted us to changes needed to improve communication with local primary care providers (PCPs). We added another PCP to our stakeholder committee and had him review all PCP-facing materials and the process of getting the patient’s COMPASS care plan into the hands of the patient’s PCP. During implementation, multiple hospital-based clinicians shared that they still encountered hesitation or resistance from PCPs who wanted to use transitional care management billing codes and viewed the study as competition for revenue or patients. This real-time feedback allowed us to improve our communications with both the PCPs and the clinical teams delivering the intervention and let them know of alternative billing codes (identified by the clinical sites, not the research team) and emphasize our goal of working collaboratively to improve the transitional care and outcomes of patients.

Importantly, by bringing together patients, community-based service providers and hospital-based providers, it became clear that there were gaps in care that patients could easily identify and that providers were unaware of but eager to address. As one stroke coordinator shared with us,

“[What] COMPASS has really done for us is identify some holes that are in our program and the speech therapy is a prime example… I didn’t know before starting COMPASS that these things were getting missed or they weren’t being done or the patients were struggling like they were…. You don’t know what you don’t know, and I certainly had no idea. So we have been able to work through and do some education and set up some processes where we can limit these missed therapies and missed opportunities for incorporating resources for the patient.”

The cross-sector collaboration in the study also gave community agencies an entry point into their local hospitals which, in the past, they had not been able to establish on their own. There were multiple points throughout the study in which these stakeholders drove engagement activities that clearly strengthened the study. For example, the study pharmacist saw opportunities, knew of an existing network of community-based pharmacies that offered enhanced services, and had critical personal connections that made it possible for the study team to link a community-based specialty pharmacist to each of the 40 hospitals (via their CRNs). These community pharmacies often were able to provide to patients evidence-based interventions (smoking cessation, diabetes management, blood pressure monitoring, etc.). The study team recognized the value that these community pharmacists offered, but, over the course of implementation, they emerged as markedly more critical partners in care than the team had initially expected. If a pharmacist had not been on the study team, the team would not have been aware of the opportunities he identified; nor would the team have had the credibility or social capital that he had in his professional network to forge these statewide partnerships and connect patients with community services to support their recovery. Expanding beyond the hospital perspective enabled us to treat the patient holistically.

The study team made several observations after including diverse stakeholders in relation to socioeconomic status, urban/rural location, and racial representation. First, regardless of socioeconomic status, location, or race, patients and caregivers voiced the same problems with usual care after stroke:

Not knowing who to call as soon as they recognized they had cognitive and/or physical deficits that were not detected in the hospital.

Survival and full recovery require that the patient has an able and willing caregiver, yet many stroke survivors live alone or have ailing spouses who themselves need caretaking.

Not having a roadmap to follow to recovery.

These unmet needs were universal and shaped the intervention. It was particularly eye opening to hear from highly resourced patients and caregivers that they – in spite of their social and economic advantages – were overwhelmed by having to managing post-acute care. They told us that they did not see how people with fewer resources could cope or ever fully recover. Their lived experience pushed the team to design an intervention that assesses the patient comprehensively, and also assesses the caregiver’s ability to care for the patient. The intervention also calls for a single person, trained in stroke, to be the clear contact person for the patient; and this information is communicated to the patient and/or family in a myriad of ways (introduction at bedside, business card, refrigerator magnet, in paper work, by mail, second introduction on follow-up call after discharge). The guidance stakeholders gave for a roadmap to recovery (Care Plan) is described in Table 1.

Second, stakeholder diversity in terms of rural/urban and racial representation produced creative solutions to common problems. Rural hospitals had clinical teams that were exceptionally effective at anticipating and successfully addressing implementation problems. They attributed this prowess to knowing most people in the small hospital and community and being able to leverage those relationships. The solutions developed at rural sites were shared with and then adopted by urban sites. For example, a rural site could not identify the protocol-specified RN within the hospital system to serve as the main contact to the patient. But a clinician did know of a community paramedic program, rooted in the African-American community that was already making home visits. The site argued that a community paramedic, who was trusted by community members, could effectively function in the protocol-specified role and the protocol was amended. This solution was then used in other sites.

Several clinical stakeholders who were African-American and started as advocates for their African-American patients became trail blazers in implementing adaptations of the intervention after the measurement period (during the sustainability phase) to further address their needs. For example, to address remaining transportation barriers, they consolidated members of the care team to one location, and made the comprehensive assessment of the patient a televisit. The study team’s next study is to test the effectiveness and implementation of a televisit vs in-person visit for comprehensive post-acute stroke care now that Medicare is covering telemedicine during the COVID pandemic and this form of the intervention is sustainable.

Discussion

In this study, we actively elicited and incorporated input from a diverse set of stakeholders in one of the first large-scale pragmatic clinical trials of transitional care in the USA. This qualitative assessment highlighted ways that patients and caregivers shaped the design of the intervention, enhanced caregiver and clinician training, designed ways to improve patient recruitment and participation, and made patient-facing materials more useful to other stroke patients and their caregivers. Furthermore, it revealed ways that engagement of acute care hospitals’ providers and administrators, post-acute care providers, local pharmacists, and primary care physicians facilitated uptake of a complex intervention. Unexpectedly, it also revealed ways that stakeholders themselves benefited from engagement with the research team.

The majority of the literature to date on stakeholder engagement in research has provided general guidelines or has focused on the barriers to successfully engaging stakeholders [Reference Johnson29]. A common conclusion in these studies is the need for real-world evidence of successful stakeholder engagement methods. Findings presented in our paper describe specific ways that active engagement of a broad-ranging and diverse set of stakeholders shaped a large-scale pragmatic clinical trial. While the majority of studies that have shared successful engagement practices have primarily focused on only one aspect of the study (e.g., design, implementation), this study describes ways that a complex intervention bridging acute and post-acute community settings was shaped by stakeholders throughout its design, conduct, and dissemination.

Patient and family stakeholders were typically delighted when asked to join or advise the study team. Indeed, many patients sought out the study team when they heard about it through the local media. Patients and caregivers were typically motivated to collaborate as partners when learning that the research team wanted to learn from their experience to improve care for others. Community-based health and social service providers were similarly motivated to serve as stakeholders, even those who had no prior research experience, due to the shared mission of improving health and wellbeing of either stroke patients in particular or older individuals more broadly. Patients were open and honest with their input and feedback. At times, patients and families would couch their critiques of the hospital care they received by explicitly praising their providers (paraphrasing: “I loved my nurses, but xyz has to change”). Patient and family stakeholders frequently expressed that being able to contribute to the study was critical to their own healing. Specifically, they stated that bringing awareness to gaps in care and being part of the change that they hoped would reach thousands of other patients helped them rebuild their confidence in public speaking, redirect their grief or anger into something productive, make sense of their new life, and fulfill their new purpose in life.

This paper has limitations. Due to resource constraints it was simply not feasible for the study team to deeply engage with all stakeholders and also transcribe and tag all data with codes. Engagement activities were tracked but some were captured in less detail, truncated or summarized in REDCap forms. However, in those cases we often uploaded documents that captured rich details about the engagement activities. The strength of this paper is that the team documented the vast majority of engagement activities and systematically engaged stakeholders from design to dissemination and acted on stakeholder advice.

Stakeholder involvement in the COMPASS Study produced lasting benefits to stakeholder groups beyond the scope of the study, from publicly available, patient-friendly educational materials (https://www.nccompass-study.org/), to education of hospital-based clinicians on what it means to deliver patient-centered care, to strengthened community partnerships, to sharing evidence that informed policymakers about the need for primary and secondary prevention care in stroke. Very importantly, stakeholder involvement in the study produced a new patient-centered consent model for future pragmatic trials [Reference Andrews30].

Inclusion of stakeholders from underrepresented groups enhanced the project overall. For example, working with an African-American patient stakeholder on the development of the consent model was extremely educational. While she was advocating for all stroke patients, she was particularly attuned to the deep mistrust of the health system that African-Americans in North Carolina still feel. She advocated for a delay in the timing of consent (ensuring that patients were not asked to consent when they could not fully process what was being asked of them). She changed the language used on the consent form and study brochures because she did not want a single patient to think they would be receiving suboptimal care if assigned to the control group (for fear that perception would undermine their recovery). While the study team could offer language the IRB approved, she could offer language that would not turn patients away from the study.

A common charge against stakeholder involvement is the amount of time and resources required. We agree that, for stakeholder engagement to be meaningful, it does require paid research effort, study infrastructure, and payment for the time that patients and community organizations provide to the study. The study budget was established in 2015. It was important to reimburse stakeholders equitably and consistently. See Supplement 4 for our policy and procedures for reimbursing stakeholders. The study paid $20 per hour to patient and caregiver stakeholders for their time spent preparing for meetings, attending meetings, reviewing materials, and travel when necessary, etc. For health professional and corporate stakeholders there was overlap between their established (paid) work and study needs, therefore they were not compensated at an hourly rate. All stakeholders were eligible for compensation for their time in focus groups and interviews which the IRB defined as research. It was necessary to balance compensation across a large stakeholder base while not limiting input from stakeholders or exceeding study budget. It is now 2020, and as our team prepares other grants and associated budgets we have increased the hourly rate to 30–40 dollars per hour (depending upon the size of the grant) as we feel that 20 dollars per hour should be increased for the value that stakeholders bring to each study.

It should be noted that a collaborating advocacy organization declined reimbursement. A community-based organization negotiated a 10,000 dollar per year flat rate. Reimbursement went to the organization, not to the individuals engaged in the study. Unlike community-based participatory research, stakeholder engagement in research can lie along a continuum of meaningful participation, which provides some flexibility in time and resource investment. We believe that the short-term costs of investing in stakeholder engagement pays off over the long term. For instance, it may take longer to create a consent process and consent form that patients, caregivers, and the IRB approve, but it may support patient recruitment and hospital retention over the course of the study.

Future studies should directly test the impact of elements of study design, implementation, and dissemination that were informed by stakeholders vs those that were not to continue to advance the science of engagement in clinical research. Future research should also quantitatively test the effect of stakeholder engagement on patient recruitment, patient or provider behavior, and patient-centered outcomes. Another area ripe for study is understanding how patients personally benefits by contributing to research projects (not as subjects, but as study team members) and if and how that might affect their own recovery. This will require additional time and resources but is critical to strengthening the inclusion of stakeholders in the design and implementation of future studies and programs.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.552.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all COMPASS partners who made this study possible. Research reported in this publication was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (PCS-1403-14532). All statements in this presentation, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

We acknowledge REDCap support from the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR001420), supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.