A recent article published in Vietnam's Communist Party newspaper Nhân Dân titled “Vacant Lands, Bare Hills into Green Forests” epitomizes a now-common reforestation story in Vietnam. The essay describes a forest plantation project in the hills above Quảng Trị. It begins with a description of the area in the 1960s, then a denuded landscape of bomb craters, and explains how it has been turned into a prospering tree plantation. People from a local highland minority group own these plots, and the essay notes their social transition, too, from nomads to green capitalists:

These communes inhabited by ethnic minorities … had a very difficult life in the past. Their primary cultivation practices were “find, cut, burn, sow,” moving from place to place, burning forests for swidden plots; but now they have fixed agriculture, permanent settlements, increased production and stable lives … in which many ethnic minority households have risen to become millionaires from planting forests and rubber trees.Footnote 1 (Nguyễn Văn Hai Reference Nguyễn Văn Hai2014)

This double transformation, converting bare hills into industrial forests and ethnic minorities into prosperous citizens, is an example of a process of state-building achieved through the reappropriation of “empty land, bare hills” (đất trống, đồi trọc) and the state-supported development of tree plantations. Since Vietnam recognized private leases in such lands in 1993, provincial governments and private investors have reforested over five million hectares of “bare hills” and other public lands in this manner with mostly acacia, pine, and rubber trees. Vietnam's total forest cover bottomed out at about 25 percent of total area in 1993 and has since rebounded to over 44 percent, mostly via tree plantations (McElwee Reference McElwee2016; Meyfroidt and Lambin Reference Meyfroidt, Lambin, Nagendra and Southworth2010; Pham et al. Reference Pham, Moeliono, Hien, Tho and Hien2012).

This popular regreening story in Vietnam fits a readily understood modern timeline beginning with the Vietnam War and turning after the Đổi Mới liberalization reforms in the 1990s. Undoubtedly, the hills near the former DMZ were severely damaged by the war. However, this timeline also obscures a deeper environmental past. Unlike many areas of highland forests, many of the hills had already been cleared of their forests long before the American war began. A French explorer in 1877 noted broad swaths of terres abandonées here, and imperial Vietnamese surveyors in 1833 listed roughly half of these hilly areas as “idle wasteland” (hoang nhàn, thổ phụ).

This article follows a longer history of this hilly “wasteland” not only to challenge a presentist framing of environmental decline but also to recognize the historic roles that people played in producing these spaces, even “wasting” them via fire and livestock grazing. This local history of land clearing and customary uses also figured into colonial visions of them as “wasteland” requiring state repossession and regreening. As Dove (Reference Dove1998) and Peluso (Reference Peluso2009) argue with respect to state seizures of “dead” land for rubber plantations in Borneo, terms such as “idle,” “waste,” or “vacant land” (đ ấ t trố ng) had multiple valences, meaning very different things to individuals than to states. For people living and working in the hills, what states viewed as “wasteland” had value as a commons, providing fuel wood, pasture, and precious space for tombs. The historical causes of persistently bare hills were both socially and ecologically complex. Annual burning, grazing, laterite clays, and intense erosion played a role, but so did coercive taxes and state demands for labor. As a “wasteland,” the bare hills were more than just an effect of unsustainable, early modern practices, colonial policies, or even the Vietnam War. Both as a historically open zone and more recently as ground zero for tree plantations, the hills were physically and socially produced.

Writing the history of such a “wasteland” is one way to decenter imperial, colonial, and nationalist teleologies that tend to emphasize the environmental “footprints” of state actions but not the reverse. In Asian studies, recent environmental histories of rivers and river deltas (Biggs Reference Biggs2010; Zhang Reference Zhang2016) point to the agency of floods and uncooperative landscapes in shaping state environmental responses; like cities, deltas and waterways have long attracted attention from historians as keys to the development of trade and agriculture. By contrast, “wasted” or blighted areas such as urban slums (Harms Reference Harms2014) and treeless hills have long posed different problems for states but received much less attention from historians. These less attractive spaces have what Taylor (Reference Taylor1998) might call surface histories of their own, histories oriented to local concerns that often followed different trajectories from national or colonial imperatives for land “improvement.”

While such problem areas may not have attracted the same level of attention, works in Chinese and Indian environmental history in particular offer useful historiographical approaches. Perdue's (Reference Perdue1987) study of Qing programs to reclaim the hills fringing Dongting Lake in Hunan details a locally centered approach to examining social conflict and local resistance to imperial mandates at specific lands and lakefronts. Elvin (Reference Elvin2004), Marks (Reference Marks2011), and others have extended similar regional approaches to other sites and dynasties, showing how local resistance or cooperation with imperial initiatives often varied with the balance between perceived economic rewards and relative autonomy. In studying the role that “wastelands” played in shaping colonial practices and politics, Indian environmental historians highlight the agency of troubled lands in shaping the spaces of colonial rule and in complicating European notions of value, waste, and environmental conservation. Rangarajan (Reference Rangarajan1994, 150) notes how a Mughal clear-and-hold strategy in the Uttarakhand Hills, cutting down forests to catch tax evaders, opened these spaces to British colonial troops who then claimed them for the Raj. Guha (Reference Guha2000) focuses on caste conflicts in marginal lands, noting how they invited colonial interventions. Gadgil and Guha (Reference Gadgil and Guha1992) also show how older caste and ethnic conflicts stymied colonial reclamation in some places. Geographer Vinay Gidwani (Reference Gidwani2008) uses the contested “wastelands” of Gujarat to explore a colonial and postcolonial “discourse around ‘waste.’” He notes how British officials used Lockean notions of value and depictions of the “physical infirmity and cultural inferiority of Indians” to lay claim to lands contested by rival castes. He then shows how caste politics reworked colonial and postcolonial schemes, complicating the discourse (Gidwani Reference Gidwani2008, 19). While the political and social circumstances of hills in central Vietnam differed significantly from these other places, customary land uses and shifting positions vis-à-vis imperial and colonial states were common features of their clearing, “wasting,” and regreening.

Especially in the colonial era (1884–1945), debates over certain hillsides in central Vietnam often highlighted deeper conflicts in colonial land policies, even spurring foresters to fashion “green” solutions to these ecological and social problems. Similar to Grove's (Reference Grove1995) study of British responses to land desiccation in southern India, I suggest that the French colonial “discovery” of these degraded lands and subsequent colonial failures to stop deforestation shaped colonial ideas about environmental decline and propelled the interest in exotic trees. This emphasis on the agency of “wasteland” in shaping colonial practices corresponds somewhat with Vandergeest and Peluso's (Reference Vandergeest and Peluso2006) study on local forestry customs in Siam, British Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies. They show how European studies of forest communities shaped colonial approaches to forest resources that differed significantly from one state to another.

Writing the history of an “empty” space that many imperial and colonial observers tried to ignore is, in some respects, a revisionist project, too, in that it requires close attention to particular hills, land claims, and village-state disputes. While imperial and colonial records described widespread deforestation in the hills, especially closer to the coast, my intent in writing a local history is not to generalize for the region but rather to pinpoint the terms of local cooperation or resistance in the processes of clearing, “wasting,” and regreening the hills. This article draws together a mix of village records, imperial surveys, and colonial documents about a relatively focused area of hills around the former imperial capital of Huế to articulate a historiographical point that this local “wasteland” had a history that often ran counter to imperial and colonial attempts to reclaim it and, in certain cases, informed state ideas about degradation and recovery.

Clearing the Hills

For Vietnamese, the central coast was an early modern frontier where the armies of Đại Việt established uncontested rule in the late 1400s. Vietnamese chronicles note that this coast between the Ngang and Hải Vân passes (see figure 1) had since the tenth century been a border zone dividing Vietnamese and Cham polities north and south. Archeological sites and ancient texts suggest that ancestors of both groups built settlements here much earlier; and tributary records suggest that the lowland rainforests that once covered the hills produced some of the most prized goods in the Nan Hải trade: camphor, agarwood (Aquilaria crassna), ivory, and cinnamon (Hardy, Cucarzi, and Zolese Reference Hardy, Cucarzi and Zolese2009). Tropical hardwoods such as ironwood (Erythrophleum fordii) and dipterocarps (Hopea odorata and Hopea pierrei) supplied valuable timber for local construction. Even after the Lê dynasty established official territories in this region, Cham and Việt inhabitants produced culturally mixed settlements along the coast while mostly Katuic-speaking peoples lived in the hills and participated as upland partners in a forest products trade.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Hill region of the central coast. Data from VMAP0, ESRI Inc., and Open Street Map. Figure by author.

Vietnamese migration and settlement picked up quickly after successful naval campaigns against Cham polities further south, and the hills fringing coastal villages took on special roles in the settler economy. As a source of fuel wood, bamboo matting, timber, and metal ores, they were an industrial complement to the rice production that expanded in estuary polders. In the villages near Huế, civic life was concentrated on a narrow, inland coastal plain while satellite settlements in the hills and estuaries supplied essential goods (see figure 2). Local village histories and family genealogies often detail initial land grants and founding ancestors (including many ethnic Chams) who claimed lands in this plain. These founders and their initial plots often formed a sort of ancestral beachhead as family descendants over generations moved out to start new, “upper” (thượng) and “lower” (hạ) hamlets. Family tombs for “founding ancestors” (thủy tổ) and family shrines (lăng họ) became pilgrimage sites while descendants built more tombs in a village's hill territory (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Founding villages on the Inner Road. Topographic map, Société Géographique d'Indochine, 1909, republished 1943; elevation data and commune boundaries provided by Thừa Thiên–Huế Province, 2011. Figure by author.

This system of village development accelerated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with Nguyễn Cochinchina's rapid economic and territorial growth. In 1558, a general loyal to the then-deposed emperor, Nguyễn Hoàng, became viceroy of the region and established a southern Vietnamese domain that became known colloquially as the Inner Road (Đàng Trong) (Li Reference Li1998, 37). The narrow, inland coastal strip with its string of villages crossing it was that road. Bounded by lagoons, dune fields, and barrier islands, the inside coastline offered shelter from winter storms and seaborne raids. As commerce increased along this inland corridor, villages developed cottage industries in the hills that, in some villages, became central to village culture. As village residents moved to new hamlets, they often named them by adding an “upper” (thượng) or “lower” (hạ) suffix to the founding village's name (see figure 2). This pattern of village names, centered on the coastal strip with upper and lower extensions, placed particular hill zones within the legal territory of these village clusters. Most of these upper and lower names disappeared in colonial and postcolonial maps, but the first colonial topographic survey retained some. An excerpt from a 1909 map (see figure 2) shows origin villages clustered along an isocline approximately three meters above sea level with some upper and lower hamlet names. A recently discovered, seventeenth-century land record from Dã Lê Village details the village's founding and splitting. Dã Lê Chánh Xá Village (Dã Lê Communal House in figure 1) was founded in 1460. In 1515, the village split into four parts: Dã Lê Thượng (hills), Dã Lê Chánh (communal house), Dã Lê Hạ (estuary) and Lợi Nông Dã Lê (a hamlet along Lợi Nông Canal) (Thừa Thiên Huế Province Library, n.d.). (See figure 2.)

As Li (Reference Li1998) and others note, the boom in foreign trade and warfare in Nguyễn Cochinchina during the 1600s led to more intensive industrial activities; nowhere was this more pronounced than in the iron-rich hills above Phù Bài Village. Over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this village's economy and identity grew around all aspects of iron production. As a main supplier of iron and steel to the capital, Phù Bài ran smelting kilns around the clock, especially during the long, west winters to keep the kilns running (see figure 2).Footnote 3 The village's iron production was so important that the Nguyễn lords exempted the village from the military draft for almost two hundred years. Instead, the village's men, women, and children worked in hazardous mines and smelters. During years of intense fighting during the Trịnh–Nguyễn War (1627–73), annual production topped over sixty metric tons. This industry was intensely consumptive and polluting, as the kilns required tons of charcoal fuel and each ton of iron resulted in several tons of waste slag (Bùi Thị Tân Reference Bùi Thị Tân1999, 60). Phù Bài's village culture was organized around iron, too. Its family shrines and five communal houses were tied to five hereditary guilds responsible for each stage of iron production: mining, transport, charcoal production, smelting, and blacksmithing (78).

While the Nguyễn lords spurred dynamic economic growth around coastal ports and continued to take new lands further south, imperial land policies and increasingly onerous tax demands on upland villages losing their natural resource base produced an environmental and political crisis by the mid-1700s. The Nguyễn court struggled to keep people in deforested uplands. In the hills around the capital, it exacerbated the problem by keeping most of these lands subject to strict public oversight and heavy taxes. Upland land grants were generally not hereditary but instead listed as “public fields” (công điền). Retaining them depended on a lessor's good tax standing, and many people who could not pay the taxes gave them up. Even high-ranking officials could not easily obtain hereditary lands. A descendant of a founding family in Dã Lê Village was required to keep 90 percent of his hilly, poorly irrigated acreage listed as public fields (Thừa Thiên Huế Province Library, n.d.).

By the mid-1700s, Nguyễn Cochinchina's pattern of expansion into the hills had reached some limits. Many villages could no longer meet imperial obligations for taxes and materials while feeding their own residents. Over 125,000 people in Thừa Thiên Province were farming just 75,000 hectares of land, mostly in the intensively engineered patchwork of estuary polders. Less productive fields in the hills were left fallow (Nguyễn Khắc Thuần Reference Nguyễn Khắc Thuần2007, 173). Meanwhile, the Nguyễn lords continued to heavily tax upland areas (Li Reference Li1998, 134–38).

A political crisis swept through areas of Nguyễn Cochinchina in 1771 when a tax revolt in the hills of Bình Định expanded into the Tây Sơn Rebellion (1771–1802). After taking control of coastal ports around the former Cham stronghold of Vijaya, the brothers leading the rebellion cut off rice shipments traveling from the Mekong Delta to Phú Xuân and effectively starved the capital into submission (Trương and Đỗ Reference Trương and Bang1997, 69). This period of political upheaval worsened conditions in the villages along the Inner Road. The hills could not supply Tây Sơn's demands for industrial goods, and observers noted that the occupation government took desperate measures, even melting down church and pagoda bells, to substitute (Cadière Reference Cadière1915, 306). Estuary fields had reached their productive limits, too, and by the 1790s severe famines racked parts of the central region (Dutton Reference Dutton2006, 166–70).

Reframing the Hills

The last imperial government, the Nguyễn dynasty (1802–1945), issued a new round of land reforms and surveys, but these measures had little effect on “idle, fallow lands” in the central region. The new government, a military regime under Emperor Gia Long and his generals, continued to conscript soldiers in campaigns to expand territory in Cambodia and while putting down rebellions. These military activities drained farm and industrial labor from struggling villages on the Inner Road, undermining any effort to reclaim fields or do more than collect fuel wood and let animals graze in the hills. Formerly wealthy villages such as Phù Bài suffered a postindustrial decline in the 1800s. In 1808, the imperial government revoked the village's 200-year exemption from military service and requested 500 soldiers from the village (Viện Sử Học Reference Viện Sử Học2006, 717). Emperor Gia Long (r. 1802–20) also extended traditional tax schemes, exerting high payments from those farming “public fields” (công điền) in less productive areas. A land survey of the province noted that by 1833, villages along the central coast had given up more than half of the fields in the hills as “idle wasteland” (hoang nhàn, thổ phụ) (Nguyễn Đình Đầu Reference Nguyễn Đình Đầu1997, 165).

While the last imperial government in Vietnam followed suit with many nineteenth-century states in largely historically “idle” lands, it joined in the scramble to incorporate new settlement frontiers from neighboring states. This new wave of imperial attention toward the mountains resulted in new cartographic and geographic attention to the entire upland area. By naming the hills and including them in a series of nineteenth-century maps and gazetteers, the Nguyễn dynasty reframed these areas as “idle” or “open” areas within an expanding national map that pushed national borders out into former Lao, Cambodian, and highlander territories. The second Nguyễn emperor, Minh Mạng (r. 1820–41), played a central role in guiding these efforts, incorporating Khmer, Cham, and highland areas while also pushing to assimilate these regions and “cultivate” new imperial subjects (Choi Reference Choi2004).

Nguyễn dynasty territorial surveys and writings on upland peoples played a key role in repositioning the hills as a “midlands” and also in structuring new views of land and people that informed colonial views on these areas just a few decades later. Davis (Reference Davis2015, 325) shows how Minh Mạng's imperial project, especially ethnographies of highland peoples, guided early French ethnographic work. Nguyễn officials traveled through the hills and past old imperial border gates to new trading posts deeper into highland territory. These communities of mixed ethnic-Vietnamese and highlander people served as nodes for imperial efforts to “cultivate” (giáo hóa) highland subjects through various means of soft power, trade incentives, and the threat of harsher, military reprisals.

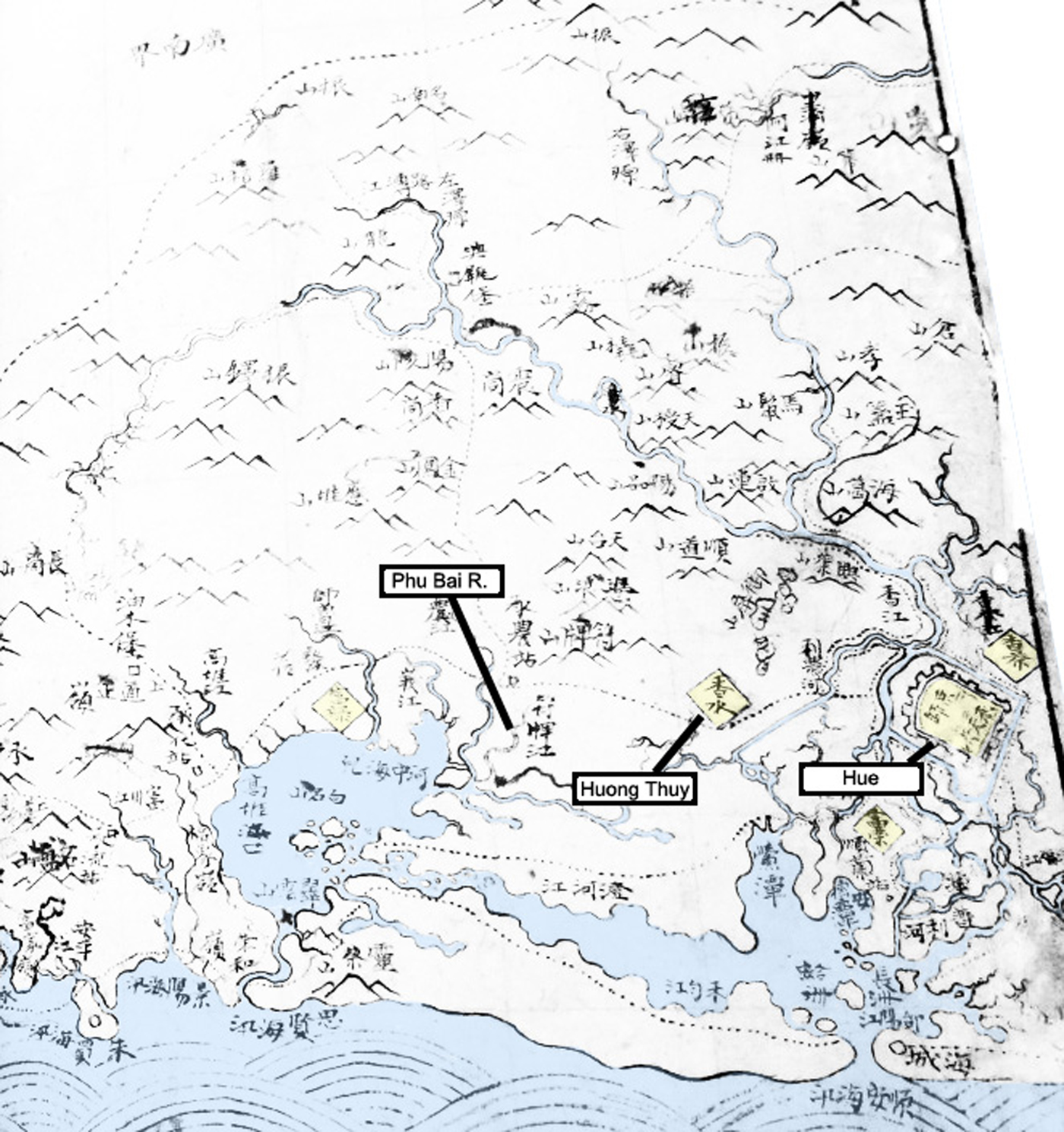

The corresponding cartographic project, especially focused on these new highland frontiers, was also significant for providing new details about the hills. The hills shifted in their spatial significance from upland (đất thượng) backcountry in a traditionally coastal-oriented kingdom to a relatively bare, midland (đất trung) zone dividing the coast from the expanding highland frontier. One of the first maps published in this era, a national atlas published in 1832, shows this more detailed attention to the hills reflected in many named hills (see figure 3). While the Nguyễn had experimented with Western, planimetric mapping as late as 1820, the atlas's use of a coastal orientation and symbolic conventions similar to late-Qing cartography (Hostetler Reference Hostetler2001) reflects the second Nguyễn emperor's preference to return the kingdom to a closer association with Chinese models of statecraft.

Figure 3. 1832 map of Thừa Thiên Huế Province (Social Sciences Library of Hồ Chí Minh City 1832).

Also significant with respect to the state's developing claims to highland peaks, the map uses a Sino-Vietnamese term “sơn” (山) for “hill” or “mountain” to name these hills forming the historical Vietnamese backcountry running from the Inner Road to headwater (nguồn nước) trading posts. As Nguyễn officials pushed further uphill in the 1840s and 1850s, later geographic texts used “sơn” to describe hills settled by ethnic Vietnamese (người kinh) but other terms to describe mountains in the highlands. One of the last Nguyễn gazetteers written before the French conquest, Đại Nam Nhất Thống Chí, introduced two foreign terms, “động” and “cốc,” to describe mountains inhabited by highlander groups.Footnote 4 This last set of works reorganized Vietnamese territory from two to three elevational domains: Thượng (non-Việt highlands), Trung (Việt midlands, bare hills), and Hạ (the coastal plain) lands (Bùi Văn Vượng Reference Bùi Văn2012, 603; Nguyễn Văn Tạo Reference Nguyẽ̂n Văn Tạo1961).Footnote 5 While such works did little if anything to change land uses in these “midlands,” they nonetheless were pivotal in shaping the cartographic imaginations of French explorers who built from Nguyễn knowledge bases in forming their own maps.

Colonial Encounters in Terres Abandonées

French encounters with these hills actually commenced several years before the military invasion through an unusual diplomatic deal. After a series of unequal treaties had concluded, in 1876 the French government voted to present Emperor Tự Đức with a gift of five French ships to help the kingdom reestablish a small fleet.Footnote 6 French naval officers traveled from a camp in Đà Nẵng to deliver the ships and temporarily captain them. This gift of warships and a two-year training mission brought a novel reconnaissance opportunity for one French explorer who took a capitalistic view of the empty hills. Retired naval officer and cartographer Jules-Léon Dutreuil de Rhins spent two years captaining the gunship Le Scorpion while exploring the countryside around Huế. His detailed attention to Nguyễn coastal defenses informed the French navy, while his gaze from the “royal road” to the hills rendered deforested hillsides into verdant spaces for new enterprises. His popular, published account of the journey, Le Royaume d'Annam et Les Annamites, included two of the first detailed maps of the Huế area for European audiences. The maps and the travel diary hewed close to the genre of the day, functioning as both entertainment and promotional literature for colonization. He wrote about the lower reaches, “almost entirely deforested, uncultivated, which mediate between the mountain and the plain.” He described this area as ideal for “cash crops: sugar cane, coffee, tobacco, cotton, mulberry, cinnamon, pepper, etc.” and he added that “the climate of this province is much healthier than Lower Cochinchina or the Tonkin Delta.” In light of the cholera epidemics that had raged in colonial ports such as Sài Gòn, the bare hills offered a healthy respite where “Europeans could acclimatize, directing industrial and agricultural establishments and really do the work of colonization” (Dutreuil de Rhins Reference Dutreuil de Rhins.1879, 289).

Recalling Gidwani's comment on British colonial efforts devaluing “wasted” landscapes before claiming them for colonial, capitalist uses, Dutreuil de Rhins likewise took many opportunities in the text to criticize the Nguyễn government for its failures in the hills. He also laid blame on the villages below them, chastising “rapacious” mandarins and “lazy” villagers for not investing labor in developing cash crops in these empty lands (Dutreuil de Rhins Reference Dutreuil de Rhins.1879, 282–83). Confined to the geographic reach afforded by his Vietnamese guides and traveling no further than the kingdom's rear gates, he focused on these hills while leaving the highlands a gray-stippled blank space labeled “mountainous region inhabited by the Moïs” (savages) (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Carte de la Province de Hué (Dutreuil de Rhins Reference Dutreuil de Rhins.1879, inset).

A closer look at this map (see figure 5) shows that the French cartographer not only carried forward Vietnamese sites such as “royal garden” and “tram” (administrative post, trạm) but he also used terms such as “uncultivated” and “abandoned,” conceptually clearing the hills for forms of colonial development that he repeatedly alluded to in his travelogue. Through gentle shadings, he hid many ecological “truths” in this region, deep gullies incised along streambeds and razor-thin layers of topsoil. Villages names, cemeteries, and place names melted into generalized names—“village,” “uncultivated plain,” and “scrub” (see figure 5). Despite his boosterish view on colonial development in the hills, the 1884 treaty that established the Protectorate of Annam prohibited French entrepreneurs from claiming the hills. After vicious fighting with Nguyễn forces in the north, the treaty protected the imperial court's sovereignty over village affairs, especially public fields (công điền), private fields (tự điền), and unincorporated lands. The treaty limited ownership of these “crown lands” to Vietnamese nationals and indigenous courts.

Figure 5. Detail from Carte de la Province de Hué (Dutreuil de Rhins Reference Dutreuil de Rhins.1879, inset).

France's legal access to these “fallow” lands only began in 1897 after a prolonged, royalist insurgency that started in 1885 and continued sporadically until 1896. French expeditionary forces, thousands of colonial troops, moved through the hills above Huế to pursue royalists who retreated to bases in the mountains (Brocheux and Hémery Reference Brocheux and Hémery2009, 52–55). After the movement was stopped, a new governor general, Paul Doumer, pressed a new legal attack on “vacant” lands in the protectorates of Annam and Tonkin. He pressured a new, more cooperative Nguyễn monarch, Thành Thái, to sign a joint proclamation ceding all public and unincorporated lands to the colonial government. Doumer touted this accomplishment, certain that it would be remembered as a pivotal turning point for Indochina:

[T]he King abandoned … his prerogative to dispose of assets not already allocated to public service, and as a consequence to concede vacant lands without masters. This provided the means for colons to settle in Annam, and we know they will make good use of it. (Doumer Reference Doumer1902, 92–93)

Thành Thái, eighteen years old at the time, signed away the crown's rights to the hills and mountain frontiers as well as all “public fields” and “military salary fields” in the lowlands. He gave up a major source of crown revenues while legally dissolving village communal claims to the hills (Bienvenue Reference Bienvenue1911, 104–8).

Lawlessness, Imperial Complaints, and Communal Resistance

This abrupt legal shift in the colonial government's control of public and “waste” land may have replaced imperial claims with the swipe of a pen, but it did not solve the long-term issues of ecological degradation nor did it completely erase customary claims to the hills. When the Resident Supérieur of Annam (RSA) office attempted to distribute plots of land to entrepreneurs, it found very few takers. It reached out to high-profile Vietnamese collaborators with hopes that they might take up cash cropping, but the few contracts issued were fraught with loopholes protecting prior access to the hills.

One contract shows how both village claims and colonial military occupation undermined new enterprises. The contract awarded 125 hectares of hilly terrain above Dã Lê Village to one of the most prominent imperial officials who joined with the French forces after 1884. Hoàng Cao Khải was the viceroy of Tonkin under Emperor Tự Đức before French forces defeated his army in 1883. Unlike peers who joined the royalist insurgency, Khải continued to serve the imperial and French governments under the protectorate treaty. In 1897, he returned to Huế to advise Thành Thái to accept the land deal. A sketch map of the hilly property and caveats in the contract reveal that, despite colonial maps and Doumer's claims, Khải's land parcel was anything but “open” or even abandoned. The contract protected villagers’ access to ancestors’ tombs for all holidays and anniversaries, and parcel boundaries were modified to allow a wide path leading from the village into the center of the parcel (see figure 6). On one side of the parcel, it also indicated other troubling features: a military “artillery polygon” and firing range (Vietnam National Archives 1900). If Khải developed the parcel, he would have to work around these other uses. Instead, the aging official left Huế and returned to the north. He became a district chief (t ổ ng đố c) in Hà Đông and left the hills to the RSA and the villagers (Fourniau Reference Fourniau1989, 169).

Figure 6. Parcel map of Hoàng Cao Khải Concession (Vietnam National Archives 1900).

Besides these legal caveats undermining colonial enterprises, villagers and the imperial government's advisory council also clashed with the RSA to defend customary access in the hills. In one case, they challenged the colonial military in a matter that traveled up the chain of command to the governor general and the commander of Indochina's military. As France expanded its military before World War I, the colonial military made new use of old firing ranges in the hills. Beginning in 1906, it commenced an annual, live-fire artillery training school in the hills above Thần Phù Village. It took place on a denuded hill that before 1884 had been a popular stop with travelers on the royal road, the Eastern Wood (Đông Lâm) (see figure 2).Footnote 7

A series of letters from 1906–13 involving residents of Thần Phù Village, the Nguyễn Emperor's advisory council, and colonial officials highlight the multiple ways that villagers used customary claims to challenge colonial authority over the spaces and especially the timing of its drills. Each year, the Third Battery of the Colonial Artillery in Tourane (Đà Nẵng) sent fifteen officers, fifty European artillerymen, fifty indigenous artillerymen, fifty mules, and six horses to a weeklong artillery fire school held on the denuded knolls above Thần Phù.Footnote 8

While lasting only a few weeks, the timing and daily requirements of the fire school represented a noisy invasion of the hills and a violent disregard for the village's cultural life. Every year, the artillery unit conducted the fire school during the Lunar New Year. It not only disrupted celebrations with loud explosions, but also required villagers to feed and house troops with no compensation in their homes during the holiday. The French officers commandeered the village communal house and stabled their horses and donkeys in the yard of the Buddhist pagoda. In 1911, the village council wrote to the emperor, petitioning him to intervene before the camp commenced. The emperor, via his Privy Council (Viện Cơ Mật), addressed the matter to the RSA, explaining that during Tết villagers made annual visits to their ancestral tombs in the hills. They prepared offerings for their ancestors in their homes, and two days before the New Year they visited the pagoda to make offerings, plant bamboo, and pray. The Privy Council made a modest request that the artillery school commence after the third day of the new year, once village rituals had been observed. However, it also pointed to the deep hostility and pain caused to the village: “[T]o move the [ancestral] altar to receive the [enlisted] and to abandon worship to serve, these are things that are contrary to the feelings of local residents and that would generate mutterings on their part” (Vietnam National Archives 1911c).Footnote 9 Despite the emperor's request, the military went ahead with the school as planned.

This conscious decision of the military commanders to ignore and disrupt the village's rites had ripple effects, upsetting civilian members of the colonial government. French civil service officers from the district and province wrote to the governor general complaining about this wholly avoidable, provocative conflict. The Resident of Huế sided with the villagers, writing to his military counterpart that all administrative and judicial business in the district stopped for several weeks because of the fire school (Vietnam National Archives 1911d).

Villagers in Thần Phù also did not stop writing letters; however, their requests highlight a more entrepreneurial view of the matter in the hills. Via the sympathetic district official, they suggested that the colonial military might erect a permanent camp on the hill, thus taking the burden of feeding and housing troops from the village while potentially creating a new source of jobs. Théophile Pennequin, commander of Indochina's military, refused the base proposal as too costly but recognized the value of compromise. He assented to paying the village for its food and lodging costs. On the timing issue, however, he did not budge (Vietnam National Archives 1911a). The province chief, exasperated and near the end of his tour, wrote one final note to Hà Nội, noting that timing the school during the holiday was an especially spiteful move, sure to cause long-term resentment (Vietnam National Archives 1911b).Footnote 10

In some cases, the elimination of royal and traditional village authority over woods and fields accelerated new environmental crises. Colonial observers at times expressed shock at scenes of unchecked forest destruction as zones of clear cuts and bare hills expanded. One of the more culturally poignant examples occurred not in the backcountry but in the royal gardens fringing the French quarter in Huế. Doumer's 1897 claim dissolved royal rights to the pine groves and abolished the royal guards who protected them. People, including colonial soldiers, cut the trees for fuel wood, leaving the pines vulnerable to storms and fires. The diminished pine groves found a particularly energetic avatar in Father Léopold Michel Cadière. A Jesuit priest who had lived in Annam since 1892 and a major contributor to the École française d'Extrême-Orient, he wrote with alarm about the pines in a journal he founded, Le Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Huế. Years of neglect and growing camps of soldiers mobilized for the war in Europe had decimated the royal groves. In one essay, “Save Our Pines!” he recounted his horror upon seeing a colonial soldier hacking away the roots of one of the wood's largest pine trees to sell as matchsticks. “I was stunned, I was angry, I was heartbroken.” He referenced the 1897 edict and blamed the damage on the colonial regime for eliminating the royal guards who traditionally patrolled these properties. He recalled traveling to the gardens with students and parishioners before the land law in 1897. He described shadowy, old groves of twisted, great trunks. Many had been planted by royal family members and bore brass, commemorative plaques. He then described for his readers the scene in 1916, vistas of damaged and downed trees with wide gashes of red soil in gullies running up the hills. Besides illegal cutting and harvesting, a severe typhoon in 1904 worsened this destruction, toppling many sick trees. He wrote, “Today it is the guards themselves who cut the pines. Today is unbridled havoc, devastation beyond measure. We must act” (Cadière Reference Cadière1916, 442–43).

Unchecked cutting and burning, especially in hills where there were few commercially exploitable stands of timber, produced a number of environmental responses among the protectorate's small group of foresters. The RSA government devoted the bulk of its forestry to exploiting highland stands of old-growth timber across its impossibly long territory, leaving hills to local users (Thomas Reference Thomas2009). Colonial foresters and district officials were too few and did not typically work with communities or pay much attention to annual burning of brush. In 1918, Annam's senior forest inspector, Henri Guibier, weighed in on this problem, expressing deep concerns about the effects of burning on erosion and Indochina's forest stocks. He had graduated from the “cradle of forestry,” the École Nationale des Eaux et Forêts in Nancy, and like his friend Cadière wrote extensively on Annam's forests for local and French audiences. Like Cadière, Guibier took a more nuanced view on modes of forest clearing, distinguishing between highlander cultures that rotated crops and the uncontrolled fires consuming scrub in the hills. He took to the pages of Cadière's Bulletin with essays, and in the forest service he joined his colleagues to advocate for forest preserves to study regional biodiversity (Thomas Reference Thomas2009, 122–23).

While Guibier did not express much admiration for highlander cultures, he was quick to note that customary swidden burning (rẫy) in highland forests with rotation was at least sustainable compared to the annual cycle of dry season burning in the hills. In the hills, he complained that colonial officials viewed every type of burning as a traditional practice, called it rẫy (swidden), and “that excuses everything.” He took special aim at the same slopes that had attracted Dutreuil du Rhin, blaming colonial officials and the villagers who used them as pasture for not “improving” them. In discussing the fires that annually ravaged these hillsides, he took pains to disassociate them from burning in the highlands. Fires here burned through thousands of acres of scrub in one dry season, leaving blackened hills followed by grasses, a sort of “management by clear cut with no reserves, a sort of sartage.” In the “bare hills,” he noted how perpetually fire-cleared sections gave way to grass, and that with respect to forest cover, the annual fires destroyed all vegetation without chance for regrowth (Guibier Reference Guibier1918, 31).Footnote 11

Regreening and Local Agency: Past, Present, and Future

This ecological assessment of widespread destruction permitted Guibier, as he stayed in Huế for over twenty years, to advance a regreening response to what he viewed as wasteful burning. He became one of Indochina's strongest advocates for reforestation via exotic species, especially Australian eucalypts and filao (Casuarina equisetifolia). His optimism, as historian Frédéric Thomas (Reference Thomas2005, 39) suggests, reflected a more general interest among foresters in the 1930s to rapidly expand wood commodity markets through reforestation of “miracle species.” Guibier was not alone in his enthusiasm for exotics. Eucalypts, particularly Eucalyptus globulus, had by the 1930s become a companion species for white settler colonies worldwide. Colonial foresters in South Africa aimed to “wean” natives from native species by introducing eucalypts, and in the Nilgiri Hills of Madras, they replaced shifting agriculture traditions of native hill groups with plantation frontiers of eucalyptus (Bennett Reference Bennett2010, 42). Guibier followed suit in Huế, opening new nurseries for eucalypts and filaos (Guibier Reference Guibier1941, 148). By then, just one tree nursery near the royal tombs remained dedicated to the traditionally preferred, Sumatran pines (Pinus merkusii) while newer nurseries sold the exotics (Vietnam National Archives 1912). (Even more telling by their absence, there were no nurseries selling native tree seedlings.) The following words of Guibier, published in the Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Huế in the months after the arrival of the Japanese Imperial Army, capture the forester's optimism for this new form of botanical colonization:

Elsewhere, around Hue, Tourane, in the North, the South, several interesting species have been tried: Eucalyptus robusta, resinifera, citriodora.

— Citriodora? It must be good?

— Stop by a warm summer evening at the nursery of Pho-Ninh, 23 km. from Hue in the north, when the young plants are already tall, tight, thick, and full of sap, undulating under a light wind and

— ‘Sounds and perfumes turn in the evening air.’ (BAUDELAIRE).

— “Yes, but it also pays, the Eucalyptus?”

— Not yet. It will come. Do you know the history of this coffee plantation in South America, where the Eucalyptus was at first only an accessory, and which, when the crisis came, became the principal and made the fortune of the plantation? It is recommended to form wooded pasture, at least with the species with clear foliage and whose leaves take a vertical position during the hours of great sun. (Guiber Reference Guibier1941, 148)Footnote 12

Despite his optimism, the Indochina War (1946–54) prevented him from engaging in any widespread reforestation in the hills.

Nevertheless, these local, colonial ideas about “wasted” hills and their possible salvation via “miracle” trees persisted with a new generation of Vietnamese foresters who took over from Guibier in the Associated State of Vietnam (1949–54) and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, 1955–75). Huế’s first postcolonial chief forester, Nguyễn Hữu Đính, continued Guibier's enthusiasm to reforest with exotics and worked with new foreign experts coming from the United States and Australia in the 1960s. Đính was responsible for developing new nurseries and plantations in secure areas. Later, he supported the National Liberation Front. He retired from government service in 1960 and stayed in Huế after 1975 to develop a forestry school at Huế University. While the fighting in the hills west of Huế had reached unprecedented levels of destruction by 1973—saturation bombing, chemical defoliation, napalm drops, and base construction—Đính and many forestry colleagues in both Vietnamese governments envisioned a postwar future with new regreening schemes. After the RVN and the communist Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) agreed to a cease-fire in January 1973, Đính sent a public report to his fellow foresters and PRG officials in Paris suggesting that they work quickly to develop a viable forest policy with fast-growing species that might support industries such as pulp and paper. He took advantage of his retirement status to offer advice to all sides, stating that the cease-fire presented an opportunity to “plant trees, make flowers” [make peace] and “cease forest destruction” (playing on the term “cease-fire”) (Nguyễn Hữu Đính Reference Nguyễn Hữu Đính2008). While socialist forestry in the 1980s failed to regenerate forests over much of this land, more recent efforts after the privatization reforms have succeeded, at least in extending green cover if not in reproducing biodiverse forests.

In the present, terms such as “bare hills” and “waste land” continue to operate not only as physical descriptions of degraded lands but also as discursive tools used by state officials and local people in negotiations about the legal, political, and ecological terms of these new uses. Baird (Reference Baird2014) emphasizes this multivalent nature of similar terms in the politics of reforestation in southern Laos, noting how people in different levels of society alternatively use or challenge classifications such as “degraded land” and “degraded forest.” This essay has argued that these conflicts over terms are tied not only to global exchanges of ideas but also to deeply rooted local histories shaped by past conflicts, past land uses, and past claims. Presentations of “waste land” in the past often served as justifications for imperial and colonial calls for land reclassification and land reform. At various moments, “discoveries” of widespread degradation triggered episodes of imperial- and colonial-era environmental angst. Emperor Minh Mạng sought to push past the “idle, fallow” hills to build economic links in the still-forested highlands. Cadière responded to decimation of the pine groves with a call for the colonial government to post guards to protect them as natural and cultural heritage sites. Guibier took aim at lowlanders burning the hillsides for pasture, producing permanently treeless slopes. He then played a central role in propagating exotic species to recolonize these slopes. The Nhân Dân story advances a new twist on an older “wasteland” story, contrasting new developments and regreening with episodes of American military destruction. Like imperial and colonial actors in the past, the article not only positively depicts recent regreening policies but also reinforces a particular story of wartime “clearing” followed by state-centered, successful reclamation using acacia and rubber seedlings.

A sited, environmental history approach shows continuities as old ideas of “waste” and reclamation circulated over multiple periods of discovery, mapping, and attempted reclamation. At moments, it shows continuities in the ways that people living in such “bare” lands in the past articulated their own economic and personal ambitions vis-à-vis a challenging environment and volatile state politics. In the 1700s, many people did this with their feet, leaving struggling hillside plots for other frontiers. In the early 1900s, villagers in Thần Phù claimed traditional access to ancestral tombs in an unsuccessful bid to reschedule military training exercises. Many others, the lawless indigènes in Guibier's essays, used fire to clear the hills to produce pasture.

Even today in these hills, especially on the edges of new tree plantations, foresters, conservationists, and communal leaders continue to struggle with deeper questions about the corresponding economic and political values of monoculture plantations, naturally regenerating forests, and bare land. The American War offers many a useful historical baseline, an event that violently cleared several million hectares of land and opened uncontested, state access to many “wastelands” in the postwar era. However, even at former American military sites where government ownership is undisputed, forestry officials, villagers, and entrepreneurs appear deadlocked in deeper debates over longer-term ethical and environmental dilemmas beyond the rhetoric on regreening. I observed this first-hand on a field trip with foresters and an NGO staffer with the conservation organization Tropenbos to a plot reserved for natural forest regeneration on top of a former American firebase (FSB Birmingham). The old runway was barely recognizable under a dense thicket of tree saplings and scrub. We hiked down from the runway towards a creek crossing the plot. Saplings grew from seeds dropped by birds, they explained, and there was no regular plan to thin them out as in “managed” forests. Despite the novelty of the “natural” plot and its historic location, the foresters held little hope that the plot would survive much longer. Area residents passed by carrying bundles of wood for fuel, and the NGO representative added that they were struggling to justify the plot's financial contributions via ecosystem services to local authorities. They pointed my gaze to lush stands of acacia growing in industrial plots on nearby ridges and suggested that the “natural” reforestation plot might soon follow a similar, green industrial fate. That model, they wryly noted, “worked” while the experiment in natural regeneration was missing an easily defended economic or political logic.

Environmental histories of such “bare hills” in Vietnam can be instrumental as historical interventions in these local discourses on “waste” and green recoveries. They point to deeper, more autonomous ideas of nature and culture as people take part in reforestation projects. Regreening hillsides has always been about more than just trees. Often it is a response to long-contested struggles over the boundaries separating local and state authority over these lands. A longer historical approach tuned to these struggles and local experiences of environmental change opens another possibility, too. More localized environmental histories can show how ideas of regreening as well as ideas of environmental degradation belong not only to states but also to individuals in these places. They played key roles in either advancing or slowing processes of “wasting” and regreening. The people who live and work in these landscapes deserve more attention for their roles in the local environmental past as well as more recognition in the present as they redefine regreening, what land is “waste,” and potentially new forms of a more localized environmentalism.