No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

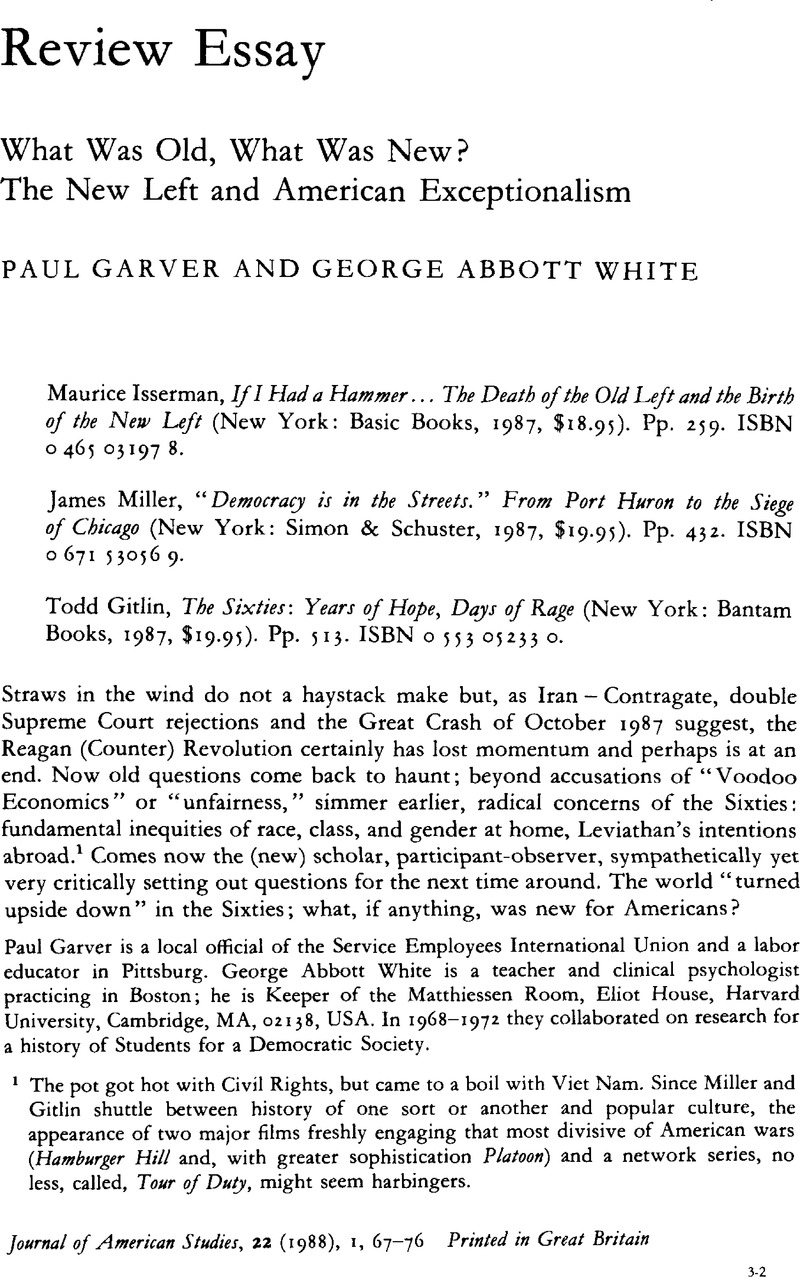

What Was Old, What Was New? The New Left and American Exceptionalism - Isserman Maurice, If I Had a Hammer … The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (New York: Basic Books, 1987, $18.95). Pp. 259. ISBN 0 465 03197 8. - Miller James, “Democracy is in the Streets.” From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987, $19.95). Pp. 432. ISBN 0 671 53056 9. - Gitlin Todd, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York: Bantam Books, 1987, $19.95). Pp. 513. ISBN 0 553 05233 0.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1988

References

1 The pot got hot with Civil Rights, but came to a boil with Viet Nam. Since Miller and Gitlin shuttle between history of one sort or another and popular culture, the appearance of two major films freshly engaging that most divisive of American wars (Hamburger Hill and, with greater sophistication Platoon) and a network series, no less, called, Tour of Daty, might seem harbingers.

2 See, by the same author, “The 1956 Generation: An Alternative Approach to the History of American Communism,” Radical America (March–April 1980), 42–51Google Scholar, and “Three Generations: Historians View Communism,” Labor History 26 (Fall 1985), 517–45.Google Scholar

3 Some, such as Alan Brinkley. have fashionably demured (“Dreams of the Sixties,” The New York Review of Books, 22 October 1987, 10–16Google Scholar) in the pages of a journal which, in 1967, published Tom Hayden's account of the Newark rebellion with a diagram of a Molotov cocktail on the cover. But Brinkley's spectator judgements lack weight. Anyone who seriously believes the New Left did not “transform the American political system,” for example, either has an exceedingly narrow conception of “transformation,” or is entirely unaware of actions by women, pacifists, welfare rights and educational activists upon the structure of that system since the time he was a graduate student at Harvard and an instructor at MIT.

4 Each study soberly appraises SDS's end, though Miller's more caustic remarks may be excessively colored less by his entry point than his experience. For a topical judgement and overview of SDS's origins, see George, White Abbott, “Remember the Weatherman?” Commonweal (22 10 1971), 91–93Google Scholar. That the government was destabilizing as much at home as it was abroad each author amply attests though, here again, Gitlin, as a participant-observer at the highest level, provides the finer detail.

5 How the New Left epithet, “Schactmanite,” could be hurled at such seemingly different versions of Trotskyism as embodied in Hal Draper, Irving Howe and Michael Harrington, finally becomes clear. What linked them all, other than the mercurical identity of their puppetmaster, Schachtman, was the New Left's nemesis, anti-Communism.

6 New Leftists were drilled in school, even elite schools, that McCarthyism was a lower-class, phenomenon: unorganized, irrational, and as dirty as the Senator's fingernails. Having inherited the perspective of a party that held national office for nearly two decades – and which would do almost anything to keep it – how hard to appreciate Republican frustration, and the lengths to which those outsiders would go to get in. For one New Left antidote, see Michael, Paul Rogin's, The Intellectuals and McCarthy: The Radical Specter (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1967).Google Scholar

7 See Theodore Draper's two-part review essay in the New York Review of Books, “American Communism Revisited,” (9 May, 1985, 32–37)Google Scholar and “The Popular Front Revisited,” (30 May, 1985, 44–51).Google Scholar

8 Miller and Gitlin each quote Potter on this important point to demonstrate that Potter, a passionate activist but careful and deliberate political thinker, rejected capitalism because it inadequately explained America as Potter had experienced it. Enormously well read, as many of the Old Guard were, Potter was neither unaware of nor unsympathetic to the Marxist critique; elements of that critique. He was convinced, as many still are, however, that the New World had to be understood on its own terms – not with some universal ideological cookie-cutter.

9 Miller's is the first work on this period to examine participatory democracy in any depth and he has been justly praised for it. Yet this effort of someone who has, after all, philosophical training and made a study of Rousseau as well, seems oddly unphilosophical in its lack of rigor. The concept's philosophical roots – growing from Plato's Republic – are unexamined, its historical antecedents (English Levellers and a string of American utopian communities, for example) are undiscussed, and its considerable successes – in practical rather than symbolic terms, from countless religious communities to the Israeli kibbutzim and the contemporary women's movement – are uncredited. Perhaps most disappointing, because Miller has searched more than the conventional literature, is that University of Michigan social philosopher Arnold Kaufmann's contribution on the subject, as teacher and author, remains unacknowledged. See Kaufmann's “Human Nature and Participatory Democracy” and “Participatory Democracy: Ten Years Later,” manuscripts in the SDS Collection, State Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin.

10 If it has a major failing, The Sixties' insensitivity to the religious dimension is that failing. Despite a concluding allusion to the Judaic tradition, Gitlin's is a relentlessly secular account which, though attentive to Counter-Cultural “passages to India,” misses the very American denominational structures, traditions, and real life actors who gave rise to the Greensboro Sit-Ins and Freedom Rides as well as sustaining much later anti-war activities such as the (Draft) Resistance. Pachem in Terris was very much on Hayden's mind when he drafted the “Port Huron Statement,” and Oglesby, Potter and others would “confess” to the importance of traditional theology and traditional ethics, as well as radical exemplars such as the Catholic Worker's Dorothy Day and Protestant Theodore Parker.

11 Oglesby was SDS's fifth president and in many respects its most extraordinary. Working class from an Akron family “come North” from the Carolinas, this Ann Arbor daytime technical writer in his thirties with a family of three was also an actor, novelist and playwright who would cut folk records for Vanguard, internationalize the Teach In movement with memorable oratory, and publish the New Left's most substantial intellectual prose, including its indictment of the Viet Nam war, Containment and Change (New York: Macmillan, 1967)Google Scholar. Like Hayden, Oglesby is everywhere cited in Gitlin and his account of the period, like Hayden's, is forthcoming.

12 ERAP was a brave but also extraordinarily divisive path for SDS, which, after internal debate and disagreement, literally ran parallel to an anti-war one. Coming on the heels of near-exclusion from Black controlled Civil Rights in the South, ERAP, among other things, gave an influential segment of early SDS a place to go as well as a continuation of earlier insurgency strategies against the benign neglect of the liberal state. Unfortunately, neither Gitlin (who was part of the Chicago project for two years) nor Miller does more than number its negative aspects; neither makes clear its importance in terms of the emerging women's movement or the crucial connection between a movement's vitality and authenticity as a consequence of its “serving the people” and a movement's decline as a consequence of that function's neglect. Neither explore the considerable secondary literature on community or community organizing, but see Gitlin's, Uptown: Poor Whites in Chicago, with Nanci Hollander (New York: Harper & Row, 1970)Google Scholar and, especially, Paul, Potter's A Name for Ourselves (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974)Google Scholar. This effort may be seen in an historic and ideological context, specifically compared with other Left “social services,” in Ann, Withorn's Serving the People: Social Services and Social Change (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984)Google Scholar. Withorn had access to ERAP files as well as interviews with ERAP members.

13 This loss was made easier not only because many of the newer New Left had virtually no contact with what Robert Coles had called “middle America,” but because those who did, including the New Left's Old Guard, had encountered there such intense racism and reflexive conservativism, even reaction – for which they were unprepared and which they had precious little success engaging and overcoming.