If print as commodity was at the heart of national consciousness formation by the end of the nineteenth century, as Benedict Anderson has argued, cinema – as a new medium for imagining the nation and as a new commodity at the turn into the twentieth century – also helped shape and amplify the idea of a national consciousness.Footnote 1 Anderson defined the nation as “an imagined political community”; to him, it was “imagined” because “the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them.”Footnote 2 While Anderson did not consider cinema as a powerful medium for imagining the nation – in the sense that film theorists do when they refer to national cinema – his work opens up new lines of inquiry into the ways in which moving pictures, the next mass-produced industrial commodity after print, helped imagine the nation during a crucial moment of transformation of the United States, both technologically and demographically. The early twentieth century witnessed a heightened sense of nationalism and nativism precipitated by recent waves of European immigrants to the US, and leading to the campaign to Americanize the communities perceived as threats to American homogeneity. During the era of new immigration, between 1880 and 1920, the composition of the American population changed drastically, with over twenty million immigrants entering the United States between 1890 and 1924. The term “new immigrants” placed Southern and Eastern European new immigrants in opposition to the “old immigrants” of Nordic and Anglo-Saxon ancestry, accentuating their foreignness, and justifying the Progressive Era need to reform and educate them.Footnote 3 As a community imagined through language, in Anderson's terms, simultaneously open and closed, the nation inspires love and profound sacrifice, but how does a subject such as the new immigrant, coerced into or unable or unwilling to speak the language of the nation, learn to participate in it? How does the nation include or exclude its aspiring citizens, when nationalism and nativism preclude the nation from seeing its different subjects?

Although Progressive Era reformers acknowledged silent film's potentially negative effects on so-called impressionable audiences – such as women, children, immigrants, and working-class Americans – they agreed on one fundamental idea: that film could educate. The role of the emerging film industry, although key in supporting the Americanization efforts – both in the local and the national Americanization campaigns targeting the newest immigrants to the United States – has been insufficiently examined by scholars of American studies. In its initial context, Americanization and Americanism – terms signifying the movement (to Americanize) and the (nationalist) ethos respectively – were often used interchangeably during the 1910s and 1920s to signify the process of acculturating immigrants through language, customs, behaviors and so on. The Americanism Committee of the Motion Picture Industry, for instance, convened in December 1919 in Washington, DC to set the parameters of the Americanization campaign, which enlisted the support of the film industry. As historian John Higham has shown, from the end of the nineteenth century to its pinnacle during World War I, “the crusade for Americanization … brought new methods for dealing with the immigrants,” revealing “the growing urgency” of nationalism.Footnote 4

As nativism and nationalism intensified during and after World War I, the term “Americanization” acquired negative connotations; if hyphenated identities thrived at the turn into the twentieth century, the war-era nationalism shaped Americanization into a patriotic enterprise, compounded by fears of racial and ethnic difference and threats to Anglo-Saxonism. Historians such as Gary Gerstle have argued that “coercion, as much as liberty, has been intrinsic to our history and to the process of becoming American.”Footnote 5 Film historians have also revealed the social and political roles of film across history.Footnote 6 Americanizers seized the opportunity to exploit the potential of this new medium to reach wider and wider audiences in the United States. Besides local organizations doing the work of Americanization on a small or large scale, the federal government itself used the new film industry in the service of Americanization, especially at the height of the Americanization movement, during and after World War I. What I call “spectacular nationalism” in this essay signals the visual affective connection of the (new) immigrants with their adoptive country. I propose that spectacular nationalism emerged as a form of immigrant affect – through what I call affective Americanization – a new line of feeling connecting immigrant subjectivity both with one's country of origin and with the United States. Affective Americanization, therefore, reinforced and disseminated through silent film, also indexed immigrant multiple allegiances. Like print and other cultural texts, silent film carried and revealed feelings and emotions; although such emotions were often stifled by institutional control, especially during the more militant phase of Americanization in the 1910s, affective Americanization as a specific site of encounter between institutions and immigrant subjects marked the immigrant viewers’ encounters with both film and institutional and national ideology.Footnote 7

In this essay I argue that, just as Americanization did not produce compliant citizens overnight, silent film as a new and powerful medium of persuasion – in its growing variety of genres, addressing different audiences – influenced the new American viewers’ transformation only in part. Of particular interest to this article is the use of film in industrial and educational contexts – which sometimes overlapped – purporting to both “educate” and Americanize the new immigrants to the United States, particularly immigrant workers. This article asks, what cultural work did silent film do for Americanization, the active and sometimes coercive campaign to make new immigrants into good Americans?Footnote 8 The films I have chosen to read as case studies later in this essay – industrial, educational, and nontheatrical films such as An American in the Making (1913), The Making of an American (1920), and others – illustrate the potential of silent film both as mimesis (or representation of ideology) and as ideology. How did silent film contribute to the mission of Americanization? Were new immigrants the innocent viewers that the American government, industrialists (like Henry Ford), and Progressive Era educators and Americanizers were imagining for immigrant children and their families? Were they complicit? Were they doubly exploited through the popular images that aimed at “representing” them, and, in their own uncritical reception of such films duped by the illusion of the medium? To answer these questions, I draw on scholarship in immigration studies and film studies, as well as archival materials in the National Archives, the Library of Congress (MBRS), Northeast Historic Film, and the New York Public Library. I rely on the theoretical work of film scholars like Lee Grieveson, Richard Abel, Giorgio Bertellini, Miriam Hansen, Katy Peplin, Gregory A. Waller, Sabine Haenni, and others. Hansen addresses the metaphor which understood film as a universal language that emphasized “egalitarianism, internationalism, and the progress of civilization through technology.” With the rise of the nickelodeon in the United States, film offered the potential to instruct and entertain through the medium's “non-verbal mode of signification.”Footnote 9 Building on Hansen's work, Bertellini notes the larger ideological work of film on early twentieth-century audiences: “to understand how films were experienced at the time of their first viewing is one thing; it is another to understand how they operated, semiotically and ideologically.”Footnote 10 Although both American capitalists like Ford Motor Company and the federal government used film strategically and complicitly in the local and national efforts to Americanize the new immigrants, I argue that early American cinema was also critical of Americanization, especially as it negotiated new immigrant concerns about labor, literacy, gender, and representation.

As industrial and educational films helped disseminate an ideal version of the desired American, silent film also helped perpetuate what Bertellini calls existing “visual patterns of national and racial differences.”Footnote 11 From its inception, silent film responded to white America's obsession with race. Early Hollywood perpetuated racial stereotypes in thousands of shorts and feature films; D. W. Griffith was a case in point, particularly in his films about Native Americans and African Americans. If other films simply glossed over the topic of race, a film like The Making of an American (1920) conceived of Americanization as a process of “whitening.”Footnote 12 In the 1910s, the popularity of films like Birth of a Nation (1915) or The Italian (1915) revealed the country's fascination with race. The typecasting of Italians revealed larger ingrained racist and nationalist rhetoric, such as certain immigrant groups’ unsuitability for citizenship. As Kevin Brownlow has shown, Irish actor George Beban, who played the lead role in The Italian, had a fundamental role in changing the film's initial title from “The Dago” to “The Italian.”Footnote 13 New immigrant groups such as Italians and Jews were targets of a new genre of films emerging in the early 1900s, especially educational films aimed at promoting good American citizenship in the context of a national panic about the new immigrants’ difference and unassimilability.Footnote 14

By the end of the 1920s, half of the US population went to the movies; by the 1930s, most of the country went to the movies.Footnote 15 The images on-screen – as attempts to escape from daily lives of toil or as private enjoyments away from the hustle and bustle of family and work – could also influence the immigrants’ sense of ethnic or national identity, and reinforce ideologies of national and racial difference. Film scholar Sabine Haenni's work on the ethnicized public sphere in midtown Manhattan reveals that European immigrants were emotionally invested “in a mediatized European immigrant scene.”Footnote 16 If immigrant viewers had access to silent films, their interpellation into the various ideologies behind the films was not uniform. Media historian Judith Thissen finds that early silent films were complicit with the Americanization of their Jewish audiences, whereas Giorgio Bertellini argues that Italian immigrant audiences in the US became, in fact, more Italian. The second-largest group of new immigrants (after the Jews), Italians watched Italian films in their United States neighborhoods, on historical Italian themes, and thus, rather than becoming more “American,” they became more “Italian.”Footnote 17 In this instance, silent film failed the Americanization project as immigrant-themed films appealed more to group allegiances in the country of origin rather than in the United States.

NATIONALISM ON CELLULOID: SILENT FILM, EDUCATION, AND PATRIOTISM

As the Americanization campaign expanded both locally and nationally during the patriotic 1910s – a decade marked by resurgent nativism and nationalism – silent film as a seemingly democratic (and democratizing) new public sphere was also a meeting ground for ideological formations vis-à-vis racial and ethnic difference. In recent decades, film scholars have started to reexamine the role of cinema at the beginning of the twentieth century, when film reached both audiences who frequented movie-exhibiting places and large audiences in industrial settings. In a 2020 study, The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema, the contributors argue for rethinking “the pedagogical usefulness of motion pictures,” recasting the history of educational cinema in terms of its institutionalization in the 1910s and 1920s.Footnote 18 Katy Peplin, for instance, argues that “Ford's films were not simply benevolent educational films granted unto the American public but also advertisements, political propaganda, and moneymaking ventures.” Similarly, Gregory A. Waller shows the extent of the film industry's influence in educational contexts in the early 1920s, supported by organizations such as the Society for Visual Education, the Visual Instruction Association of America, or the National Academy for Visual Instruction. After the National Education Association convention in July 1922, Waller shows, the film industry found new support for classroom use.Footnote 19 Giorgio Bertellini has argued that early motion pictures “maintained lasting relationships with preexisting visual forms” (such as photography) and that these relationships perpetuated ideologies of national and racial difference.Footnote 20 Silent film could serve the education mission of the Progressive Era while also endorsing political platforms and supporting the work of the Americanization campaigns across the United States.

The moving picture show arrived in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century. Its arrival coincided with both the closing of the Western frontier for white settlement and the opening of the immigration door to new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe in 1883, following the passing of the first race-based immigration exclusion legislation, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Unlike the previous immigrants, the new immigrants were not only foreign but also “white on arrival,” in historian Tom Guglielmo's term, although historians still debate the degree of whiteness of the Southern and Eastern European new immigrants.Footnote 21 The question of race (and whiteness, in particular), not of nationality, would soon determine the racial composition of the United States for several decades through immigration restriction legislation passed in 1921 and 1924. As Guglielmo has shown, in the case of Italian immigrants, anti-Italian sentiment in a variety of venues – from the federal government to newspapers and “race science” – emerged from continued questions about the legitimacy of their claims to whiteness.Footnote 22 The new immigrants’ foreignness in the Americanization campaigns was determined primarily in terms of Anglo-Saxonism; because the majority of new immigrants were Southern and Eastern European, their transformation through Americanization programs, as well as their claims to citizenship, relied on their ability to prove their whiteness or to become white.Footnote 23 Like the new immigrants, on its arrival cinema in America was “foreign” – mostly French – and threatened the stability of the local emerging cinema industry in the United States. As film historian Richard Abel has shown, by 1905, French company Pathé Frères supplied most of the films for the American market to the extent that not only did French films dominate the early American market but they also determined the shape of “American” cinema in the next decades.Footnote 24

At the beginning of the twentieth century, in the United States and in Europe, cinema became coterminous with modernity – not only as a new technology of representation, but also as a new cultural commodity of mass production and consumption. Major shifts in the film industry affected the Americanization efforts through film. As Marina Dahlquist and Joel Frykholm have shown, film as a new technology had multiple “social and cultural uses.” Industrial film, in particular, through its networks of production, distribution, circulation, and exhibition throughout the United States, offered a venue for disseminating Americanization materials. The circulation and distribution of these films – often free of charge – led to what Dahlquist calls “the institutionalization of film.” Moreover, cinema censorship efforts (and the move to clean up the motion picture industry) and the attempts to make the movie industry more middle-class also mirrored the widespread Americanization efforts more broadly, from local, state, and national programs.Footnote 25 At the same time, as Gregory A. Waller has shown, “the early 1920s saw cinema, theatrical and nontheatrical alike, widely screened and publicly debated in an America that was rife with particularly exacerbated racial, class, and political conflict in the wake of World War I.”Footnote 26 Film translated Americans’ desires, anxieties, and beliefs, at the same time as these anxieties helped form and nurture them.

In the United States, film emerged as a popular form of mass culture between 1900 and 1910, a decade also marked by growing fears of “alienism” and a growing national(ist) panic about the new immigrants’ putative difference. The French provenance of many of these early films only deepened this (white) American anxiety. As film critic Richard Abel put it, “With an ‘alien’ body like Pathé at its center, how could American cinema be truly American?”Footnote 27 Film historians distinguish between two eras in silent film: the early period from 1905 to 1917 and the period from 1917 to 1929, marked by the rise of the Hollywood studio system. Early films were exhibited in a variety of spaces, from storefront theatres and nickelodeons, parks, and cafes to vaudeville theatres and opera houses, churches, schools, department stores, and YMCAs. After 1914, when the beginning of the war in Europe made European films harder to bring to the United States, war news and American-based or patriotic films brought propaganda on American screens.Footnote 28

Silent film, a new persuasive medium, facilitated the work of Americanization in several ways: on the one hand, it purported to educate; on the other, it served local and national Americanization projects. As film historian Mark Glancy has argued, film “gained credibility during the First World War, when it was used as a medium of persuasion by all of the major powers.”Footnote 29 According to film scholar Ronald W. Greene, “Faced with the popularity of film in the first decade of the twentieth century and the cultural anxieties generated by women, children, and immigrant men congregating at the nickelodeon, both film industry boosters and social reformers looked to the educational uses of film.”Footnote 30 Reformers, industrial moguls such as Henry Ford, youth organizations such as the YMCA, and the federal government advocated for the use of film to educate. The YMCA, for instance, “distributed industrial pictures and proposed that the films would provide an opportunity ‘for developing the platform of mutuality between the managerial and working force in industry.’”Footnote 31 If we think of moving pictures during the 1910s as a form of “visual Esperanto” (film historian Miriam Hansen's term) or the medium that filmmakers and inventors predicted would take over written language and replace books in schools and libraries (Thomas Edison or D. W. Griffith), silent film was a welcome educational tool and the immigrant audiences were the ideal students.

Watching patriotic parades and messages on film, a new absorbing medium, elicited emotions about complicated, sometimes multiple, patriotic allegiances. In the early twentieth-century affective economy, how immigrant subjects decoded and negotiated forms of belonging – and the imposition of more or less militant practices aiming at effective Americanization – affected both the personal and the community. In this context, I read affective Americanization as a structure of feeling emerging at the intersection of official discourse (federal and state governments spelling out the parameters of Americanization and acculturation), popular responses to the official discourses (such as silent film), and its larger cultural negotiations. Historian of education Jeffrey Mirel calls the new immigrants’ competing allegiances “patriotic pluralism,” which he describes as a new commitment to the adoptive country and a strong allegiance to the country of origin, a desire to maintain cultural ties with one's birthplace despite new affective and political allegiances. Mirel's framework of “patriotic pluralism” shares similarities with the term “cultural pluralism,” popularized during the Progressive Era by Horace Kallen. The pervasive model of immigrant assimilation embraced by the Americanization campaigns in the 1910s was the “Crèvecoeurian myth of Americanization,” which thrived on the assumptions that immigrants wanted to become Americans and that Americanization was quick and easy. Cultural pluralism, as theorized by Horace Kallen in 1915 (“Democracy versus the Melting Pot”) and Randolph Bourne in 1916 (“Trans-national America”), argued for preserving ethnic and cultural differences. While not entirely subverting Anglo-Saxonism, Kallen argued that ethnic and cultural differences, those “inner” qualities representing the immigrant's descent, were essential in maintaining “a multiplicity in a unity.”Footnote 32 Addressing Kallen's idea of “multiplicity in a unity,” Mirel's framework of “patriotic pluralism” also captures the affective investment of immigrants in the United States through their vision of American democracy, at the same time as they maintained strong cultural and spiritual bonds with their cultural backgrounds.Footnote 33 Over the years, local (civic), state, and national organizations serving political and economic interests would exploit such affective allegiances for political gains, especially during the peak years of the Americanization movement (during and after World War I). Building on Mirel's work, I posit that silent film helped elicit and nurture immigrant audiences’ patriotic pluralist allegiances, while also entertaining them.

As the film industry developed, immigrant filmmakers and exhibitors expanded their theatrical venues to reach an ever-growing audience.Footnote 34 By the turn of the twentieth century, motion picture producers like Carl Laemml and Adolph Zukor also exhibited the films they produced; immigrants became significant participants in the movie industry, not only as exhibitors and producers, but also as distributors and actors.Footnote 35 At the beginning of the twentieth century, a typical moving picture theatre seated fewer than 300 people, had poor ventilation, and was of questionable cleanliness. In a study on “commercial recreations” in New York City, published in 1911, Michael Davis documented that the films shown in these theatres were of suspicious quality. Nevertheless, the moving picture show at the time provided the main form of recreation and was, according to Davis, “by far the dominant type of dramatic representation in New York.” Davis's critiques also extended to the musically crude songs providing sound background for the silent films, which occasionally included patriotic songs.Footnote 36 This inclusion of patriotic songs to accompany the images on-screen was perhaps not accidental, especially when the audiences were predominantly working-class and immigrant. Through visual and aural stimulation, the Americanization movement could find new recruits among immigrants and perform the work of affective Americanization.

Whereas critics like Davis condemned the quality of store shows and the films they exhibited, civic leaders and Americanizers found the potential of the new medium welcome through local Americanization projects. In 1910 Francis Oliver, the chief of the Bureau of Licenses in New York City, found silent film to be “a potent factor in the education of the foreign element and therefore an advantage to the city.” To him, motion pictures offered the immigrants who could neither read nor write a chance at understanding their adoptive country.Footnote 37 Cultural and film critic Ernest Dench also wrote in 1917 that silent films could supplement the new language of the adoptive country. “English loses its force,” Dench remarked, whereas the moving picture, “a more powerful medium” than the page or spoken word, appeals to the eye and brings different nationalities together.Footnote 38 As it soon became clear to both politicians and the film industry that films could help in the Americanization effort, state local efforts were mobilized, from Detroit to St. Louis to Rhode Island. Writing in 1917 about “Americanizing Foreigners by Motion Pictures,” film critic Ernest Dench advocated for the use of the motion picture – “which appeals to the eye” – to bring the many immigrant nationalities together in the US. He praised the work of Ford Motor and its motion picture department, led by Frank Cody, in Michigan, and also applauded the work of the St. Louis municipal authorities to educate immigrants in St. Louis about the region and about American industries. Although he mentioned no titles, Dench pointed out that the films shown in the effort to Americanize St. Louis were exhibited in places like “a Catholic church, police station, Jewish synagogue, and a public school.” The effect of displaying Americanization films free of charge in such spaces was unexpected: on the first evening, he recounted, “ten thousand children of Italian, German, Greek, Irish, and Russian parents were present, along with their guardians.” The reach of the new medium was unprecedented. Dench credited the town of Pawtucket, Rhode Island – with nine-tenths of its inhabitants foreign-born – for making the best use of motion pictures in the service of Americanization. The Civic Theatre in Pawtucket's free admission allowed immigrants to watch programs on topics such as history, biography, sociology, and hygiene, as they also enjoyed the “scenic subjects.” Dench also credited the Committee at the Civic Theatre on handling the translation of the English intertitles into the immigrants’ languages by hiring interpreters who would explain briefly the basic message of the subtitles in several languages (Polish, Italian, or Hebrew) before the screening of the movies began. In this way, film could both educate and entertain the immigrant audiences.Footnote 39

The consumption of an emerging national cinema and its use reveals more than its source of entertainment and education; it also reveals its ideology, through articulations of nationalism and interpellations of spectators into national(ist) discourses. Despite the aura of didacticism, film provided an escape from daily life and was a source of acculturation to American life. Facilitating English-language literacy (immigrants could learn English by reading intertitles aloud), films also played a key role in creating the category of the “immigrant spectator” itself. As film consumers, immigrant spectators became aware of themselves and other consumers as spectators from similar or different ethnic and racial backgrounds. In other words, the socialization provided by the new medium (as entertainment and as education), first offered by the nickelodeon, later by the feature film, led to an opportunity for socialization inside and outside the movie theatre. In this way, film served a similar function to the school, the press (including the immigrant press), and the organizations supporting immigrant communities in their assumed transition to Americanness. Silent films, however, did not produce just compliant consumers and vessels ready to be filled with ideology; they also produced critical spectators, able to distinguish increasingly between the public and the private sphere, or between ethnic and national allegiances.Footnote 40 Yet, before silent film allowed immigrant spectators to dream, it became indispensable in the Americanization movement.

INDUSTRIAL AND EDUCATIONAL FILM: AMERICANIZATION AT FORD MOTOR AND BEYOND

Ford Motor Company's Motion Picture Department, in collaboration with the company's Sociological Department and English program, used motion pictures to educate its immigrant workers in both labor efficiency and Americanism.Footnote 41 Welfare programs aimed at Americanizing the immigrant workers at Ford Motor Company were transposed on film to promote worker productivity and efficiency. Ford's experiment in welfare capitalism, known as “the Five-Dollar Day,” started in 1914; it consisted of a profit-sharing model aimed at making Ford workers change their attitudes toward work to meet the rigors of mass production, while also being compensated accordingly if they met specific standards of efficiency. As historian Stephen Meyer has documented, “the preindustrial culture of immigrant workers had to be restructured to meet the requirements of new and more sophisticated industrial operations.” The corporate assumption about unskilled immigrant laborers was that they wanted to be “elevated” both in industrial standards of efficiency and in conditions of domestic life, as the work of Ford's Sociological Department, later named the Ford Educational Department, attested. The Ford English School expanded the Ford Americanization program by taking it into the classroom. Here adult immigrant workers received the rudiments of English language training along with an introduction to American culture. The efforts of Peter Roberts, a well-known YMCA educator, were enlisted in the training of immigrant workers at Ford's Highland Park factory in Michigan. Ford's Americanization work before the United States entered World War I served as a model for Americanization programs not only in the state of Michigan but, as Stephen Meyer has shown, for the “national [Americanization] campaign for the assimilation of immigrants into American society.” Although Ford was not alone in these efforts, during World War I, as manufacturers expressed unease or ambivalence about the “foreign” workers in their factories, the Ford Americanization program became a model for transformation, showing employers that Americanization programs could remake immigrant workers into productive Americans.Footnote 42

In Ford's endeavor to educate its workers both in Americanism and in efficiency, two categories of Ford films served the work of Americanization: first, films produced by Ford's film department between 1913 and 1919; second, the so-called “educational” films, produced between 1919 and 1925, when a militant version of Americanization after the war infused both national rhetoric and the rhetoric of Ford films. Although Ford films played regularly in traditional theatrical venues and alongside educational and industrial films, the focus of this section is on Ford films shown in nontheatrical settings. In the 1910s, more than 70 per cent of Ford Motor Company's employees were foreign-born. The Ford Sociological Department aimed to Americanize the immigrant employees through mandatory attendance of the company's English School and through removal to working-class neighborhoods near the Ford plants in Dearborn, MI, and away from ethnic communities in Detroit. Immigrants were also introduced to middle-class domestic structures by being relocated to new living quarters, appropriate for the kind of citizen the company imagined. Besides American history, civics, and the English language, the immigrant workers at Ford were also introduced to table etiquette and American living standards.Footnote 43 Ford's interest in the educational potential of film led to the creation of the Ford Motion Picture Department at the Ford plant in Highland Park in 1913, when Ford Motor became the first American industrial company with a motion picture department. Ford trained workers and disseminated news to wide audiences; the materials often included news about the products of Ford Motor Company itself. As film historian Lee Grieveson has documented, “Ford's Motion Picture Department had an annual budget of $600,000 and produced films that were among the most widely distributed and seen in the silent era.”Footnote 44 From 1914 until the 1920s, the Ford Motion Picture Department became one of the largest film producers in the world, widely distributed outside the United States. As David Lewis put it, by 1918 Ford was “the largest motion picture distributor on earth.”Footnote 45

The films produced by Ford's Motion Picture Department were shown in schools and factories throughout the United States over the years. Such pedagogical endeavors included documentaries, newsreels, and travelogues, attempting to offer “a mirror” of American life – even though the mirror was pointed more toward aspects of American life of great economic and political interest to the Ford Motor Company, and less toward Ford's laborers.Footnote 46 At the same time as the Ford movies were presenting the viewers with a “mirror” of America, these films were also self-promoting; they sold the Anglo-American ideal of the self-made man: just like cars, Americans could be “made.” Ford's immigrant workers hailed from fifty-three different countries and spoke more than a hundred different languages. Ford's documented anti-Semitism reveals another facet of his nationalism; blaming the Jews for the degeneration of American society in private, he made it his public mission to “make” the “peasants” in his employ into good Americans.Footnote 47 The large distribution efforts supported these ambitions. In the early years of production, the films produced by Ford's Motion Picture Department were grouped into the series Ford Animated Weekly, and were distributed at no charge to movie theatres and nontheatrical exhibition spaces. Ford Times documented that, in 1917, Ford films were shown in three thousand theatres a week to an audience of four to five million people; in 1924, Ford News claimed that sixty million people worldwide had seen Ford films.Footnote 48 The postwar political economy also contributed to a heightened rhetoric of nationalism and patriotism, as the films in the Ford Educational Weekly and Ford Educational Library attest. As Lee Grieveson has also argued, “the issue of Americanization became particularly important here in the Ford films, amid anxieties about immigrant loyalty to company and nation.”Footnote 49 Could immigrant workers become loyal Americans while they also maintained ties with their countries of origin? Could Ford films disseminate the Americanization ethos by appealing to immigrants’ affective registers while also instructing them to become productive (and safe) workers?

Moving pictures made by Ford's Motion Picture Department instructed audiences in both mass production and capitalism, as well as the possibilities of a new visual pedagogy to transform workers into desirable, compliant industrial citizens. Scholars have only recently started to examine this large archive and to explore the role of Ford's so-called educational films. Grieveson has shown that there were “two dominant trends in the production of pedagogic moving pictures at Ford”: the Ford ideal in manufacturing, as well as the social and industrial welfare.Footnote 50 Among the films produced by Ford – many now lost – is English School, a short 35 mm film produced in 1918. It shows a teacher lecturing in a classroom, and adult students talking to each other, then leaving the building.Footnote 51 One of the early films produced by Ford Motor's Motion Picture Department, English School was about immigrant workers in line at the Employers’ Association Bureau, who were turned away because of their inability to speak English. After the film was shown in Detroit and other industrial cities, Ford Motion Picture estimated that night-school attendance increased over 153 per cent in a year as a result.Footnote 52 English literacy was a thematic concern shared by other industrial films produced in the service of Americanization. Other Ford educational films included titles such as The Story of Old Glory (c.1916), about the American flag; Where the Spirit That Won Was Born (c.1918), about Philadelphia's historic sights; Landmarks of the American Revolution (c.1920), about the Revolutionary War; and Presidents of the United States (c.1917). Other films showed the beauty and modernity of American cities: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (c.1917), Washington, D.C. (c.1918), New York City (1919). The Ford “educational films,” distributed gratis to movie theatres and nontheatrical exhibition spaces (including factories, schools, and prisons) by Ford dealers across the United States, capitalized on the growing visual instruction movement of the 1920s. They introduced viewers to American modernity, which included coverage of both industrial progress and a visual history of the US. Helping audiences see themselves – on- and off-screen – was part of Ford Motion Picture's pedagogic mission. Films like English School and others addressed primarily immigrant and working-class audiences, perceived as deficient in understanding and performing a putative good American citizenship. As examples of “visualizing citizenship” for both working-class and immigrant audiences, Ford films also contributed to the Progressive Era's mission of maintaining social and economic order.Footnote 53

Ford's Americanization program orchestrated large graduating exercises, showcasing the adult students’ complete transformation from immigrants into Americans: in modest European clothing, they immersed themselves into a large “melting pot” and emerged as new Americans dressed in identical suits, waving flags to the audience's delight, intoning the Star-Spangled Banner, and collecting their diplomas (which allowed them to file their first naturalization papers). The “Melting Pot” ceremonies at Ford Motor in 1916 showed the nation how the disciplined immigrant laborer could become a good American citizen. Clinton De Witt, the director of Americanization at Ford, described the event at the national Americanization conference:

Our program consists of a pageant in the form of a melting pot, where all the men descend from a boat scene representing the vessel on which they came over; down the gangway representing the distance from the port at which they landed to the school, into a pot 15 feet in diameter and 7½ feet high, which represents the Ford English School. Six teachers, three on either side, stir the pot with 10-foot ladles representing nine months of teaching in the school. Into the pot 52 nationalities with foreign clothes and baggage go and out of the pot after a vigorous stirring by the teachers comes one nationality, viz., American.Footnote 54

The Ford Melting Pot Ceremonies of Americanization drew large audiences and were held in public spaces that could accommodate thousands of viewers. As hundreds of graduates emerged from the melting pot, they received their diplomas and then took their place in the audience.Footnote 55 The diplomas guaranteed that they could read, write, and speak good English, which allowed immigrants to draw their first naturalization papers without other examinations. Over time, The “Melting Pot Exercises” became larger, more dramatic, elaborate, and intolerant. The Ford English classes, organized under the auspices of the Ford Sociological Department, were subsequently widely criticized for their “grotesquely exaggerated patriotism”: “the pupils are told to ‘walk to the American blackboard, take a piece of the American chalk, and explain how the American workman walks to his American home and sits down with his American family to their good American dinner.”Footnote 56 The dissemination of patriotism through performance called attention to the artificiality of these ceremonies, as well as the company's use of these patriotic exercises to publicize its capitalist project, where immigrant labor played a central part.

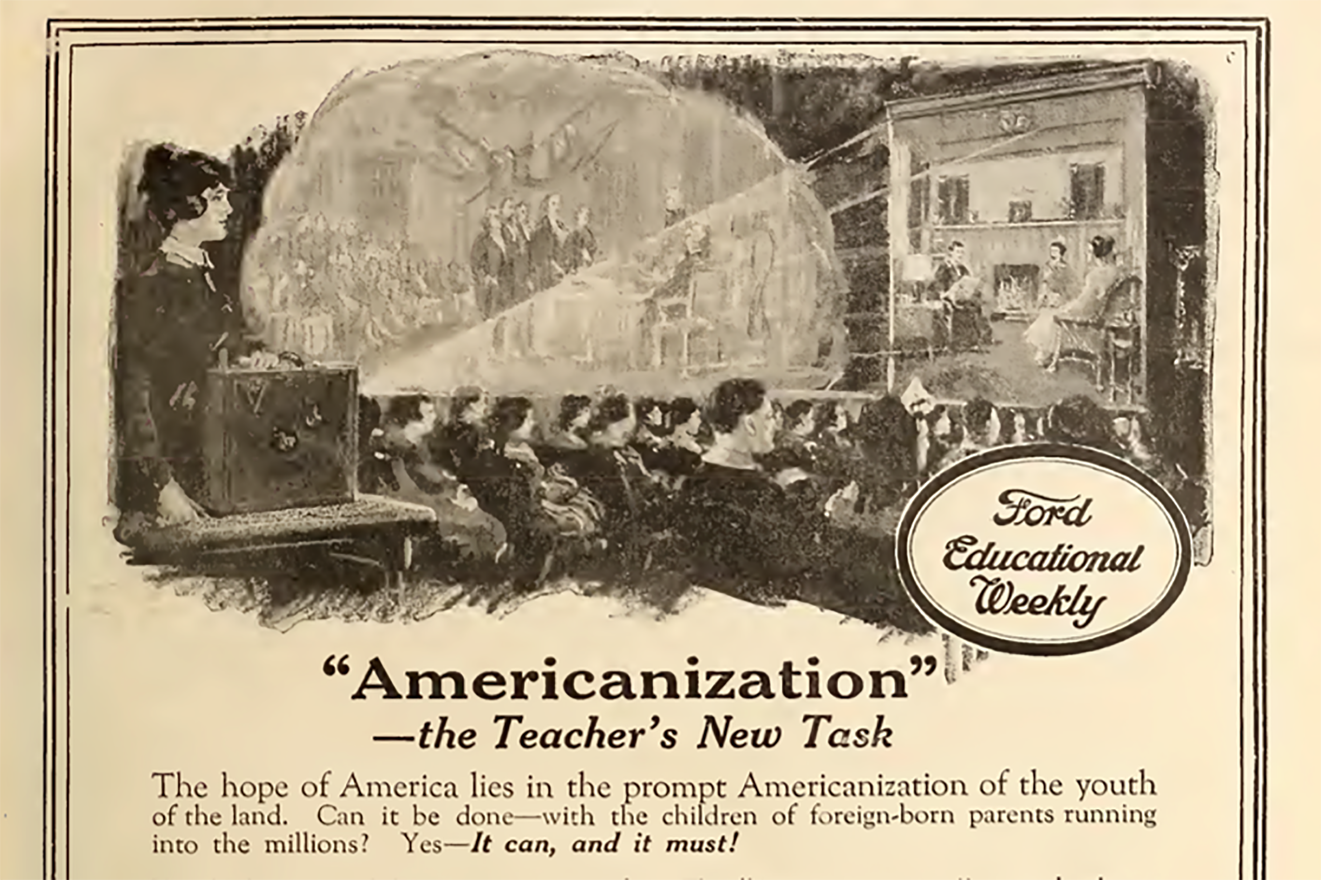

In support of Ford's Americanization mission, the newsreel-like series Ford Educational Weekly advertised the potential of film to teach “millions” and to assist in “Americanization – the Teacher's New Task,” as an advertisement in a January 1920 issue of Moving Picture Age reveals. Asking, alarmingly, “Can it be done – with the children of foreign-born parents running into the millions?” – the advertisement of Ford patriotic films answered, “Yes – it can, and it must!” Ford Educational Weekly started in 1916, and was distributed at low cost to cinemas in 1918.Footnote 57 Defining Americanization as “loyalty to home as well as country,” the films made and distributed by Ford purported to “cover history, industry, science, home life, and art.” Distributed by the Goldwyn Distributing Corporation in twenty-two cities across the United States, the films appealed to the teachers’ sense of citizenship and loyalty: “Every loyal school teacher should know what the Ford Educational Weekly really is. We want to tell you, and we want your helpful suggestions as to what new films we shall make.” The advertisement concluded with a coupon offer and the promise to connect schools with the best projector suppliers (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Moving Picture Age, January 1920, p. 7.

The images used in the advertisment also convey the utility of a good projector to classroom instruction: on the screen, a middle-class family spends leisurely hours reading and conversing in a sitting room. On the main screen to the left, the viewer sees an episode from the signing of the Declaration of Independence. This simultaneous visualization of both domesticity and history alerts the viewer to the medium's potential for Americanizing “the youth of the land,” as the advertisement puts it. The references to domesticity and Americanization as the construction of a (primarily white) middle-class domestic and heteronormative space were consistent with the norms of domesticity imposed by Ford's Sociological Department – which would soon be terminated, along with the Americanization program – during the financial crisis caused by the 1920–21 recession. Revealing the potential of visual instruction for educating and Americanizing the children of immigrants, Ford Educational Weekly also revealed the parameters of (white) American citizenship visible in the Americanization programs following World War I. Grieveson shows that the “Fordist dream of a productive pedagogical cinema failed in the late 1920s and early 1930s,” and that Ford terminated its Motion Picture Laboratory in 1932. Grieveson also explains that Ford's visual-pedagogy project ultimately ended because of practical problems in using film in educational contexts before the 16 mm film was available and because of the increased costs that the advent of sound film created.Footnote 58 Ford's narrow conception of American citizenship also alienated him and his corporation from Progressive Era groups. Only a decade later, Charles Chaplin's own Modern Times (1936) offered an acerbic critique of the Ford assembly line and the dehumanizing effects of the Fordist project.

Although the Ford welfare model declined after World War I, Ford's Americanization Program soon became a model in other states. Yet the ultimate failure of the Ford Americanization program also signaled an end to the paternalism and manipulative approach of Ford Motor to labor relations. After immigration laws were in place following the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924, as well as previous iterations of immigration restriction legislation in 1921, Americanization programs through the factory were no longer desirable or efficient to create what had been possible only a decade before: “a fully malleable workforce,” in historian Stephen Meyer's words. Immigrant workers were no longer arriving in large numbers and, because of shifts in informal worker training – where more experienced workers trained the less experienced ones – the Ford Americanization program became unnecessary.Footnote 59

Other industrial conglomerates besides Ford Motor – such as US Steel – produced and distributed industrial and educational films that not only served the gospel of Americanization but also advertised the company's (and capitalism's) humane side. States also commissioned industrial films to support their Americanization work. I end this section with an analysis of two industrial films produced and distributed during the 1910s, serving similar aesthetic and ideological goals as the films produced at Ford, and revealing further the potential for film to be harnessed in the work of both Progressive Era Americanizers and industrial capitalism: An American in the Making (1913), sponsored by US Steel, and The Making of an American (1920), sponsored by the Connecticut State Board of Education. The similarity of these films’ titles also suggests their congruent industrial and ideological mission: the “making” of an immigrant into an American at the scene of industrialization and education.

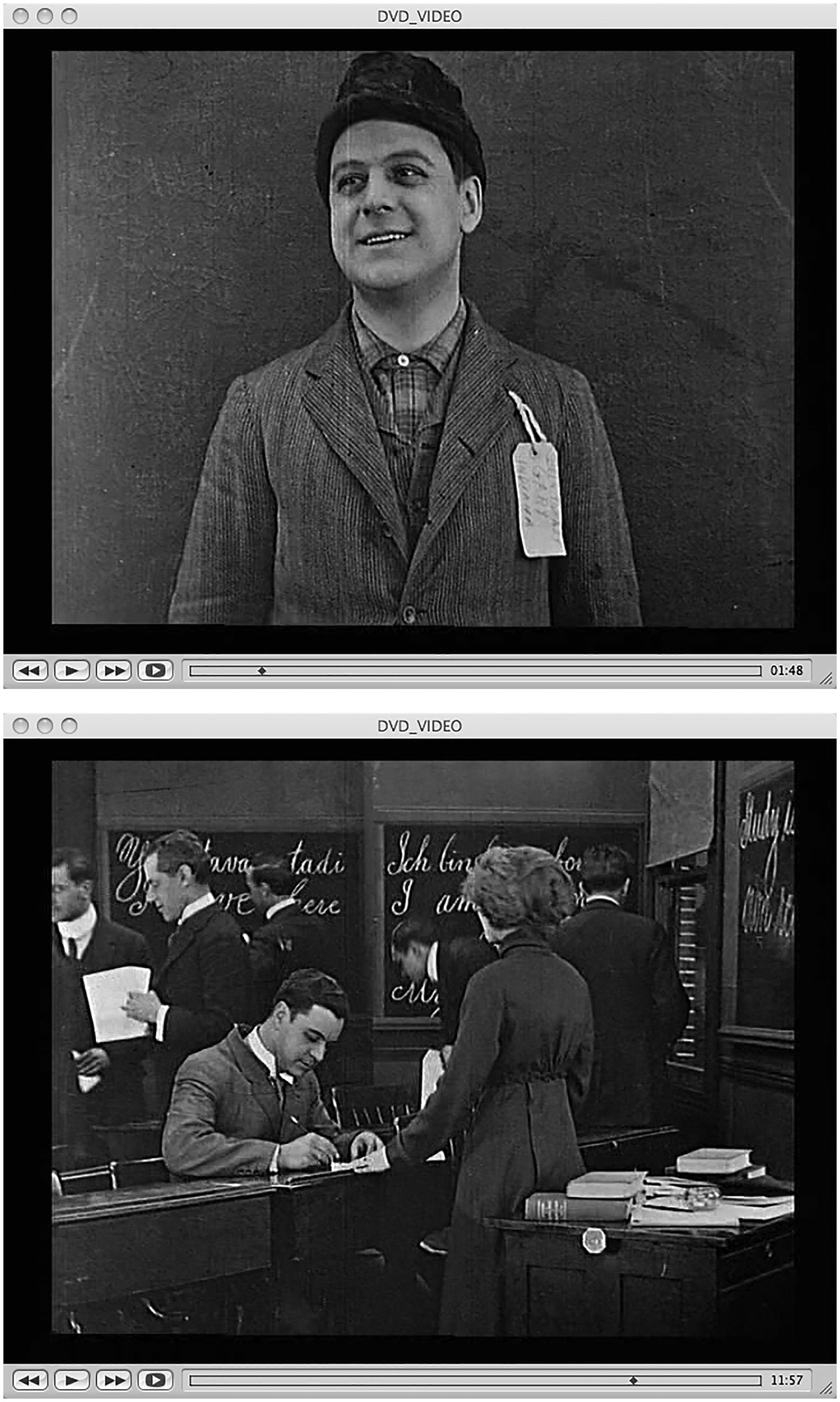

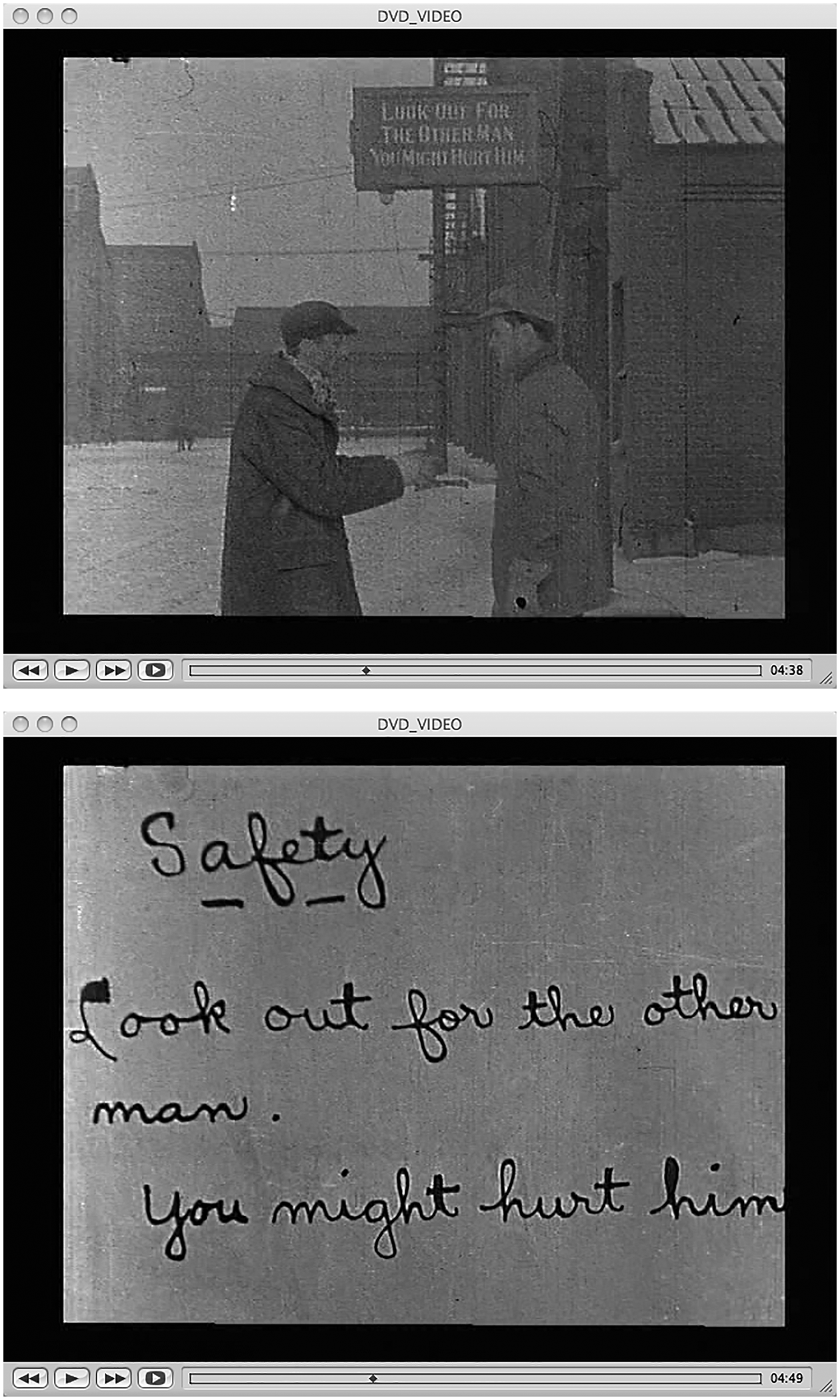

An American in the Making (1913), an industrial film commissioned by the US Steel Corporation in response to growing national concerns about industrial safety and cheap immigrant labor, purported to represent the human side of US Steel, an industrial conglomerate thriving on nonunionized, non-skilled, and low-wage labor.Footnote 60 The one-reel short industrial film (fifteen minutes) tells the story of a Hungarian immigrant, Bela Tokaji, who is “made over” into an American in six years by becoming a good laborer, after learning the safety instructions of the US Steel Corporation, and by marrying his English teacher (Figures 2 and 3).

Shot on location at Ellis Island, in Gary, Indiana, and at two other Midwestern steel companies in Illinois and Ohio, the film starts in a rural setting in Hungary, then jumps quickly forward to an American industrial setting: city scenes, industrial scenes, and scenes of education. One key industrial scene is filmed in front of the Illinois Steel Corporation, where Bela pauses in front of a multilingual instruction board at the entrance (min. 4:10). Here, safety guidelines are written in English and three East European languages, suggesting the ethnic makeup of the Illinois Steel immigrant labor force.

Immigrant labor safety is at the heart of An American in the Making, which leaves out all other types of immigrant safety (emotional, physical, and so on). In 1910, a Congressional investigation found that over 40,000 US Steel workers (almost half its employees) earned less than eighteen cents an hour, with half of them working twelve-hour shifts. President Taft had initiated an antitrust suit in 1911, which the company was still fighting at the time the movie was released. As Scott Simmon has argued, US Steel “had reasons to dramatize on film its safety measures and its concern for workmen.”Footnote 61 If one of the goals of the early industrial films was to educate audiences about technology and to demystify the industrial process, a commissioned industrial film like An American in the Making did that and so much more; it conflated capitalism, Americanization, and domesticity to serve the financial interests of a corporation. By paying little attention to the subject's story or background – Bela is Hungarian but he represents the generic malleable Southern European compliant immigrant – this industrial film sold audiences (on) the possibilities of Americanization and capital accumulation. Details throughout the film suggest the imperfections of Americanization and the film's own complicity in perpetuating them. When the protagonist's old parents hand him a letter and passage money they have received from his brother in America, the letter is written in a version of Czech, although Bela is Hungarian. For a nonunionized industrial conglomerate like US Steel, the laborers’ racial and ethnic identities made little difference, and while labor unions lobbied for restricting immigration numbers due to a surplus of unprotected immigrant hands, corporations like US Steel were ready to welcome immigrants like Bela Tokaji for minimum wage.Footnote 62 Americanization, in this case, encouraged and supported cheap (immigrant) labor.

An American in the Making reveals immigrant subjectivity as subsumed to both ideology and economics, as the film industry became complicit not only with Americanization, but also with American capitalism. The film's emphasis on the protection of laborers reveals more about the fears of conglomerates like US Steel of losing capital gains than it does about loss of (immigrant) lives. The viewers are interpellated into American exceptionalism as economic prosperity through narratives of safety: Bela's fast accumulation of both economic and social capital comes from his mastery of industrial safety equipment (Figures 4 and 5).

Showing a film like An American in the Making to immigrant workers in American industrial plants like US Steel was part of a larger national systematic effort at Americanization.Footnote 63 An American in the Making was screened by the US Bureau of Mines and by the National Association of Manufacturers, and distributed widely by the National Association of Manufacturers, often accompanied by this blurb: “Every European liner that steams into New York Harbor brings in its steerage, Americans in the Making.” A successful, albeit exploitative, American corporation like US Steel needed a film like this to clear its name. Bela's Americanization depends on US Steel: he takes the company-sponsored English classes for immigrants, learns to dress appropriately, starts dating his English teacher, and settles into a comfortable home in only six years. The final tableau paints a picture of marital bliss – Bela, his wife, and son hold each other – and American middle-class domesticity (Figure 6).

Figure 6. An American in the Making, 1913, final tableau. Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division.

Yet the film tells the domestic story in a brief succession of images in the last four minutes, after a long introduction to industrial equipment and safety. The domestic scenes reveal a bizarre combination of family life and the US Steel's benefactor grasp: the couple's son enjoys the company's leisure facilities, the (American) mother works as an English teacher for the company, and the (Americanized) father continues to thrive as a company worker. The reward of Bela's industrial labor is access to an American middle-class life, solidified by continuous employment by US Steel and marriage to his American teacher. Although these last narrative scenes set the tone for a more coherent, albeit still fabricated, story of successful Americanization, the film's first eleven minutes are radically different from the film's ending; in a series of sequences, the film instructs the viewer on industrial safety: how to use the equipment properly, such as the safety goggles, and how to navigate industrial machinery. This fractured mode of representation also glosses over Bela's years of hard labor and life as an immigrant, showing instead his swift access to American middle-class domesticity. This framing of utilitarian industrial educational material with a narrative arc around immigration reveals the potential of silent film to turn into “spectacle” the industrial safety material at the same time as it attempted to present it as a successful immigrant story of Americanization.

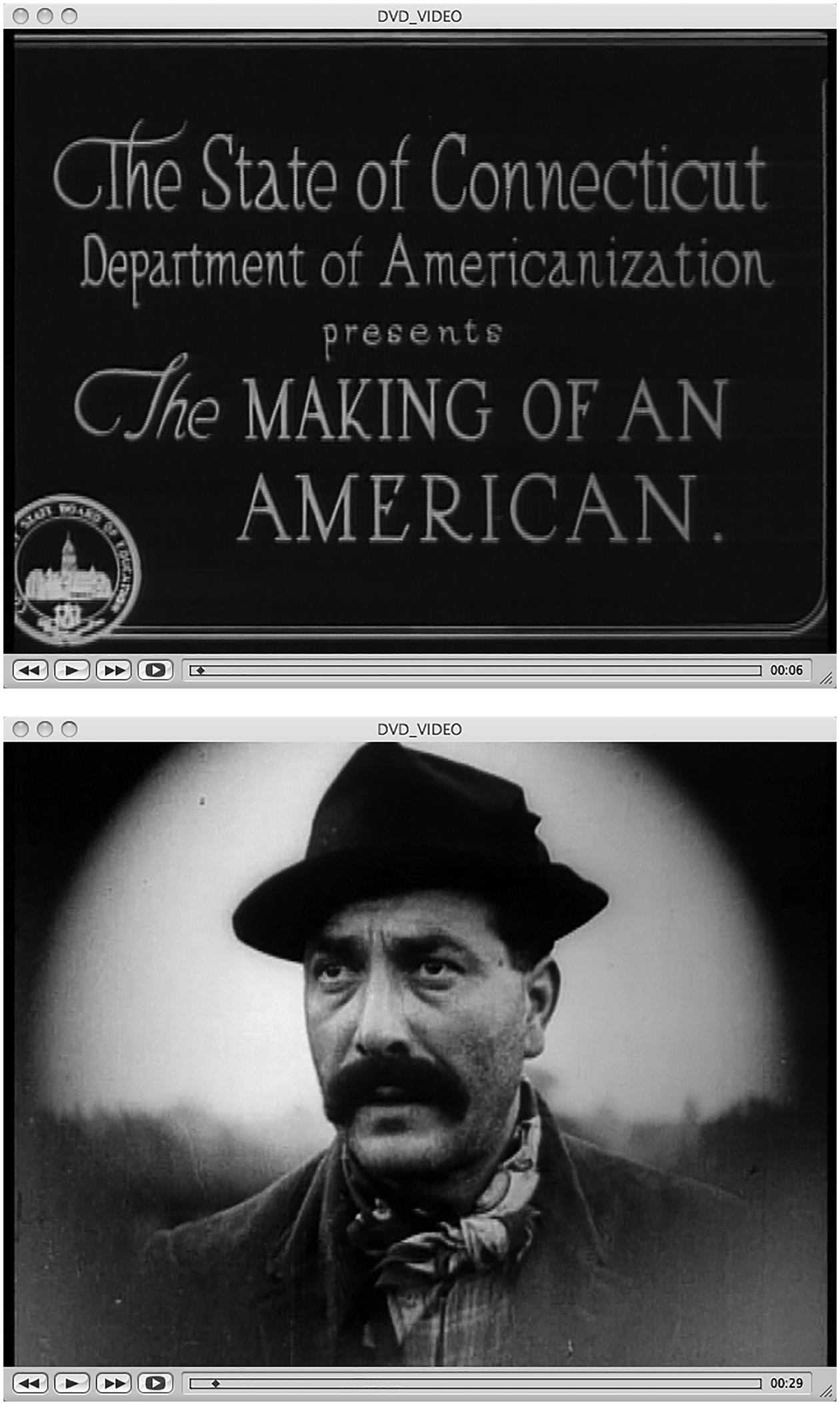

Like An American in the Making (1913), the longer and more developed silent The Making of an American (1920) had a clear marketing agenda: the recipe for successful Americanization. Made for the Connecticut State Board of Education by the Worcester Film Corporation, The Making of an American targeted industrial workers in Connecticut.Footnote 64 It promoted the image of the well-rounded immigrant man, whose success relied heavily on literacy and mastery of English. The story of Peter Bruno, an Italian immigrant with a large moustache and a disheveled appearance, revolves around his inability to speak English, his night-school education, and his rise in social and leadership status (Figures 7 and 8).

Figures 7 and 8. The first frame of The Making of an American (top); Peter Bruno as a new immigrant arrival (bottom). Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division.

Despite the film's polemic and predictable fictionalized plot, it is a useful historical document about immigration and literacy.Footnote 65 Italian immigrants formed the second-largest immigrant group in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, which may explain the choice of an Italian immigrant as a metonym for illiterate Southern and Eastern European immigrants.Footnote 66 The film shows similar “appeals to all foreigners,” including safety warnings in other Southeast European languages, thus extending both the target audience and the demographics that Peter Bruno embodies. Almost killed in an elevator shaft at the beginning of the film because of his inability to read the “danger sign,” Peter emerges victorious at the end of the film not only as a proficient English speaker and an Americanized foreigner, but also as a civic leader. In The Making of an American, English saves Peter's life. He becomes the head of the Safety Council, where he continues to fight for the well-being of his fellow immigrants. The last intertitle, in capitals, reiterates the film's didacticism: “IF YOU KNOW MEN OR WOMEN WHO DON'T KNOW ENGLISH, URGE THEM TO GO TO NIGHT SCHOOL.” The lesson in literacy that the film promotes includes social mobility, but it also reveals the limits to the future of literate immigrant laborer. The Connecticut Board of Education defined Americanization as “any process which makes a man or woman a loyal, active, and intelligent citizen,” a definition the film readily endorsed.Footnote 67

The reception of The Making of an American exceeded initial expectations, with over 100,000 viewers during 1920 and many copies sold to other states.Footnote 68 In one six-month period, sixty-three factories in Connecticut established Americanization classes. English is this film's metonym for Americanness, an idea already written into immigration restriction laws by the Literacy Bill passed in 1917. The bill (which passed over President Wilson's veto) marked not only the beginning of the immigration restriction policy, but also an increased emphasis on English-language acquisition as the essential mark of Americanness. Produced during the militant phase of the Americanization movement following World War II, The Making of an American serves as a cautionary tale and a rethinking of the ingredients for “making” an American in the next decade. Subsequent immigration restriction categories (besides literacy) and a growing nativism, coupled with an economic crisis, would soon lead to the drastic restriction of immigration from countries like Peter Bruno's beloved Italy and other Southern and Eastern European countries through the Immigration Act of 1924.

AMERICANISM IN ACTION: MOTION PICTURES AND THE AMERICANIZATION EFFORTS

Silent film was here to stay, as was its promise to “educate” and Americanize the immigrant industrial worker. The popularity of moving pictures, especially among the immigrant working class and children, was a major argument for the government's use of the medium strategically in the Americanization campaigns. In 1919, newspapers reported with confidence that “Movies Will Aid [the] Work of Making Good Americans.” The goal of the Americanization campaign using celluloid was ultimately to reach over 1,900 schools throughout the United States, a project under the direct supervision of the Bureau of Naturalization, Department of Labor:

Thousands of feet of celluloid are now awaiting the zero hour to go over the top in a drive that will carry the gospel of 100 per cent Americanism to every corner of the land. The pictures will visualize for the foreigners in our midst the message that is being sent out to them through the bureau of naturalization.

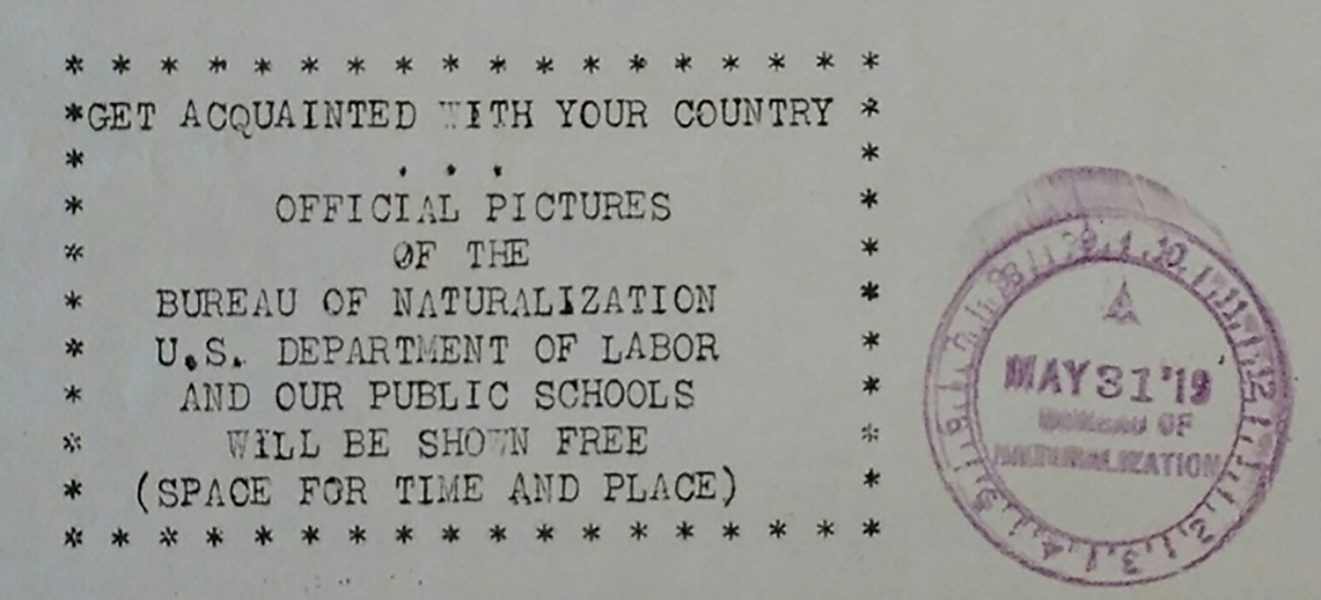

In promotional materials, the federal government enlisted the new medium to “[a]id in the work of making good Americans,” promising that these films will show “precisely what the government of the United States stands for and what it aims to do for its citizens.” The plan was to exhibit these films in night schools and to serve immigrant laborers. The films would “revel in the country's colonial history – from the landing of Columbus to the present day.”Footnote 69 A newsletter issued by the chief naturalization examiner in Chicago on 26 May 1919 announced in all capital letters, “MOVING PICTURE FILMS AND FILM POSTERS.” The films were “for use in the instruction of the foreign-born in preparation for citizenship. They visualize the subjects covered in the Free Government Textbook furnished by this Bureau. There is to be no charge for the use of these films except the necessary express charges.” A rectangular advertisement at the center of the newsletter urged the reader to “get acquainted with your country” through the “official pictures of the Bureau of Naturalization” (Figure 9). The commissioner of naturalization also expressed “hope that these films will assist the schools to induce not only the foreign born men and women, but the native born Americans who may require further instruction of the kind furnished by the English and citizenship classes, to enroll for regular instruction.”Footnote 70

Figure 9. Newsletter No. 5, “Americanization, Naturalization, and Citizenship,” Chicago, 26 May 1919. GROUP 85, The National Archives and Records Administration, The National Archives, Washington, DC.

At the National Conference on Americanization Industries in Boston, Massachusetts (22–24 June 1919), which met to address Americanization Activities in American Industries, the topic of Americanization through film emerged in several speeches. Merle R. Griffeth, publicity agent of General Electric, addressed the audience on the topic “Americanization in Industries”; he related a recent episode at a General Electric plant in Schenectady, NY, where the foreman decided to produce a film on Americanization to educate the immigrant workers, to show them “how the different nationalities have progressed from the time they left their homes in the old country to their present bettered condition in their American homes.” Another General Electric employee from the plant in Pittsfield, Massachusetts advocated for using the workers’ lunch hour to show a fifteen- to twenty-minute Americanization film.Footnote 71 Industrial films like these were desirable to companies because not only did they use the employees’ time efficiently, but they also controlled workers, as film historian Lee Grieveson has argued, in order to advance the work of capitalism.Footnote 72

In an attempt to make and distribute films promoting “faith in America,” representatives of the motion picture industry were summoned to Washington, DC in December 1919 by Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane to form the Americanism Committee of the Motion Picture Industry. A Joint Committee on Education of the Senate and the House resolved that “that the Motion Picture Industry of the United States be requested to do all that is within its power to upbuild and strengthen the spirit of Americanism within our people.” This project aimed at promoting what Secretary Lane called “concrete Americanism,” and enlisted the services of leading producers, artists, directors, and distributing agencies throughout the United States.Footnote 73 Besides providing entertainment to immigrants and Americans alike, films – both early documentaries and short feature films – also engaged Americanization or were engaged by it, in service of nationalism, publicized through both government venues (such as government documents or the proceedings of Americanization conferences) and trade magazines like Motion Picture News (MPN). Shortly after the meeting of the Americanism Committee, a January 1920 issue of Motion Picture News announced that the short-lived National Film Corporation of America was planning to adapt screenplays from eight stories in popular magazines (like the Ladies Home Journal) in order to “push Americanization.”Footnote 74

The Americanism Committee projected that these films would be “America first products” – written by American authors and using American settings. The production manager of the National Film Corporation of America, I. Bernstein, pledged the Department of the Interior his support “in its scheme for Americanization through motion pictures.Footnote 75 MPN also announced that filmmaker Ralph Ince would make a series of Americanization pictures. The first in the series was The Land of Opportunity (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Poster for The Land of Opportunity, Selznick Pictures, 1920. Note that poster advertises the film as “The Initial Americanization Production.”

This was a two-reel film written by Lewis Allen Browne, about America as “land of opportunity,” seen through the lens of Abraham Lincoln's life:

In commemoration of the birth of the great Emancipator, Land of Opportunity is released to exhibitors and it would be to the advantage of all of them to present this picture not only as a tribute to Lincoln but as an ideal subject in showing America as a wonderful land of opportunity.Footnote 76

Real Art Pictures, producer and distributor of the film, used the occasion of Lincoln's birthday to promote the Americanization movement. The film was widely marketed as “The Initial Americanization Production” of the Americanization Committee, chaired by Lane.Footnote 77 The National Americanization Committee (NAC) was formed in May 1915 at the recommendation of the Committee for Immigrants in America. Its main task was “to bring American citizens, foreign-born and native-born alike, together on our national Independence Day to celebrate the common privileges and define the common duties of all Americans, wherever born.” Besides the national Americanization Committee, there were local Americanization committees; according to sociologist Howard Hill, besides federal, state, and municipal agencies of Americanization, there were also private and voluntary agencies working toward Americanization. NAC's activities included conducting surveys in cities, training college teachers for educating immigrants, publicity campaigns in night schools, and holding Americanization conferences. Contributing largely to the standardization of Americanization work, the far-reaching and powerful Americanization Committee also offered free services and publications.Footnote 78 The politicians and movie distributors agreed: film could serve (and save) the nation.

One of the first tasks of the Americanization Committee of the Motion Picture Industry, led by Secretary Lane, was to work with film exhibitors to screen the patriotic film The Land of Opportunity on Abraham Lincoln's birthday (12 February 1920). This effort was part of the campaign to promote the Americanization movement, reaching far and wide: from Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, and Minneapolis, to Omaha, Kansas City, St. Louis, Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia. The committee declared the week of 8–14 February 1920 Americanization week; it included other patriotic exercises in all the major cities of key interest to Americanizers. Exhibitors were encouraged to use music “compositions exclusively of American authorship,” including “American numbers that are valuable from a standpoint of patriotism.”Footnote 79 Every theatre on Broadway also booked The Land of Opportunity, advertised as an antidote to post-World War I radicalism, “the most forceful blow at parlor Bolshevism ever made into a screen production.” Government officials also viewed the film in Washington, DC, and were pleased with the film's mission to combat radicalism and unrest.Footnote 80 Franklin Lane himself met with film exhibitors on 9 February 1920, reminding them of the new medium's potential – nay, “opportunity” – to bolster public sentiment: “The whole idea of this program is that we shall try to revivify the spirit of our people. We are in a slump; that is to say, we are not buoyant … we are not as sure of ourselves as we were.” Franklin Lane's appeal was calculated: “you made the people of the country feel that the motion picture was as real as the newspaper or as the pulpit – as real, probably, as the pulpit used to be when religion had more definite hold upon the people.” Film historian Steven J. Ross attributes the failure of this genre of Americanization films, such as The Land of Opportunity, to their message of acceptance of economic submission and the depreciation of the value of labor: “the anti-left, anti-labor films of the war period were paralleled by the emergence of the movie industry as a major big business and by increased militancy among its workers.” Nevertheless, film exhibitors took the opportunity to use film to sell American patriotism throughout the country.Footnote 81

Along with private and voluntary organizations, and state and municipal agencies implicated in the work of Americanization, federal agencies showed an interest in using film as they strove to create a more “practical Americanism campaign.” On 19 May 1920, Secretary Lane wrote a letter to George Kleine, a Chicago optician and entrepreneur who made and sold filmmaking equipment, asking him to serve as a member of the Advisory Council of the Americanism Committee of the Motion Picture Industry of the US. The goal of this committee was to inaugurate an active screen campaign for Americanism. One of the tasks of this committee was to develop themes for what Lane called “a practical Americanism campaign.” Kleine rose to the occasion by assuring Lane and the Americanism Committee of his company's cooperation, promoting films already in stock.Footnote 82 Throughout the 1910s, especially during the war years, George Kleine worked with the US government (the Department of War, among others) and assisted in the distribution of films for patriotic occasions. In July 1917, Kleine distributed Thomas Edison's The Birth of the Star Spangled Banner (1914) – produced to mark the song's one-hundredth anniversary – with the main purpose of recruiting men to the Marine Corps. Although the song would not be adopted as the US national anthem until 1931, the film's release in 1914 and subsequent distribution throughout the 1910s enhanced the patriotic frenzy of the decade.Footnote 83 During World War I, Kleine also contributed to the war effort by distributing films like the documentary America's Answer (1918), about the arrival of American troops in France. When the American Motion Picture Programs were released in January 1924, totaling thirty weekly program units, they promised to offer “eye-training for American citizenship,” including titles such as Yanks (1 reel), The Immigrant, America: Enduring Power of Service, and America: The Garden with a Protected Soil.Footnote 84

Although the Americanization Committee failed in its ambitious plan of releasing one film a week, the films it did release received wide distribution and critical attention for a short period following World War I, when the movie industry shifted its focus to a profit-driven business model.Footnote 85 The restriction of immigration in 1924 and the consolidation of Americanism as an intransigent race-based Anglo-Saxon ideology, along with the consolidation of the studio system in the next decade, with its host of emerging labor concerns, took the spotlight off Americanization in silent film. New popular fears of Russian invasion and the takeover of Bolshevism, concerns about labor strikes, along with fantasies of revolution, soon replaced the concerns of Americanizers about the perceived differences of new immigrants.Footnote 86 Yet, for a few years in the 1910s and the early 1920s, the promise of silent film to help in the work of Americanization galvanized the attention of politicians, the film industry, and neighborhood exhibitors ready to make Americanism their platform. A resolution adopted in December 1919 by the Joint Committee on Education of the Senate and House in Washington, DC requested that the Motion Picture Industry “do all in its power to build up and strengthen the spirit of Americanization within our people.”Footnote 87 The National Board of Review collaborated with the moving picture industry and the commissioner of immigration between 1921 and 1923 to enable screenings of both nonfiction and fiction films on Ellis Island for the newly arrived immigrants.Footnote 88 State and federal agencies continued to distribute Americanization materials in a more concerted effort immediately after World War I. The immigration restriction legislation of 1921 and 1924 – which imposed numeric quotas on immigrants from undesirable countries – shifted the concerns of both employers and state and federal agencies away from assimilation after 1924.

Silent film both engaged and occasionally challenged the nationalist project of Americanization by calling attention to issues such as citizenship and national belonging, exclusion, and the often formulaic model of the ideal American citizen – or “the good American” – that many viewers were interpellated into, particularly through the educational and industrial films. As silent film served the Americanization crusade through industrial and educational films, silent feature films – albeit not the focus of this article – also pointed to the medium's complicity in the Americanization project beyond the classroom or the factory and its potential for critique. Silent feature films such as Alice Guy Blaché's Making an American Citizen (1912) and Charles Chaplin's iconic The Immigrant (1917) engaged in a critique of both the Americanization movement and the unrealistic and prescriptive approaches to Americanization. Alice Guy Blaché's Making an American Citizen (1912), for instance, called attention to the gender barriers limiting access to American citizenship, and showed the prescriptiveness of American behavior through a series of “lessons in Americanism” that the visible alien has to learn. Although not an educational film, Blaché's commercial film took on the similar task of industrial or educational films at the time; however, rather than employing the didacticism of pedagogical film, it subsumed the “lessons” it attempted to teach to a larger cautionary tale about prescriptive Americanism. Like An American in the Making, discussed earlier in this article, Blaché's Making an American Citizen made family and the domestic sphere the primary sites of “lessons in Americanism,” yet maintained a critical stance toward the quick Americanization and almost overnight reformation. The film's last intertitle reads, “Completely Americanized!”

Similarly, Charles Chaplin offered an acerbic parody of the “immigrant problem” and a sympathetic treatment of the immigrant subject in his iconic silent feature film The Immigrant (1917), where he poked fun at the regimentation of immigrant travel and arrival “in the land of liberty.” Chaplin's film assumed Americanization as part of the immigrant's adaptation to the new country after a long and difficult voyage but did not make it central to the immigrant's new life. The Immigrant's most memorable tableau is the scene of “arrival in the land of liberty,” which offers a biting critique of the putative American hospitality. During triage at Ellis Island, Chaplin's character furtively kicks an immigration officer's behind – a scene that caused considerable uproar, especially when Chaplin was accused of anti-American activities in the 1950s – in response to the officer's similar violent act upon the immigrant's arrival. This episode captures the power imbalance between the immigration agents and the new arrivals. The physical punishment the Tramp experiences upon arrival is a metaphor for the larger forms of violence the Americanization crusade used, over and over, on- and off-screen, to disseminate the image of spectacular nationalism beyond educational and industrial film.

The emergence of cinema as a medium of great use to the Americanization campaign – endorsed and supported by the federal government, as this essay has shown – coincided with the birth of the American spectator. In many instances, the American spectator was an urban immigrant or working-class subject whose class or ethnic distinctions temporarily dissolved in the darkness of the movie theatre. Silent film was, in many ways, a welcoming public forum where racial, ethnic, and linguistic differences were temporarily suspended, an alternative public sphere for immigrants (and women) in the US, where they could immerse themselves – for a while – in a virtual space where ethnic and racial differences did not dictate their belonging.Footnote 89 As cinema became a new vehicle for “imagining the nation,” in Benedict Anderson's terms, at the turn of the twentieth century nations like the United States learned to imagine themselves and their ideal citizenry through moving images.

The spectacular nationalism that the Americanization crusade helped disseminate through film resonates in the resurgence of nativism and nationalism a century later, in our contemporary moment. In the early twentieth century, the film industry, through its industrial and educational films discussed in this essay, contributed effectively to the affective work of the Americanization campaign. The motion picture theatres – like factories or night schools – became powerful arenas for educating the immigrant, not the least in American patriotism. The federal government's intervention in enlisting the motion picture industry's service to help promote Americanization took this “education” one step further. If moving pictures promised to facilitate cross-cultural communication between people belonging to different nationalities and speaking different languages, they were also used strategically by the federal and local governments in their Americanization efforts, reaching their peak during and after World War I.