Introduction

Thirty years after the Tiananmen Square protests, the People's Republic of China (PRC) has reached ‘great power’ status. It owns the second economy (World Bank, 2019) and the largest armed force in the world (IISS, 2019). Moreover, the PRC exerts a crucial geopolitical weight in the Indo-Pacific region, which Washington considers ‘critical’ in terms of stability of the international orderFootnote 1 (US Department of the Navy, 2015). The 2017 National Security Strategy of the United States (NSS-17; White House, 2017) explicitly labels China a ‘revisionist’ power that challenges American vital interests. Beijing would be expanding the range of its state-driven economic model, massively modernizing its conventional and nuclear armed forces and persuading other states to heed its political and security agenda.

The challenge to scholars of international relations (IR), as posed by China's precipitous rise, is twofold. The first is theoretical. Although the notion of revisionist power is deeply rooted in the IR realist literature, it has always been treated as a secondary issue compared to that of status quo power. As a result, although existing studies have provided convincing insights about the actors involved in and the causes of revisionism, there are still some important gaps concerning its modes. In particular, the distinction between the revolutionary and the incremental strategies, as defined by Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1981), remains under-researched.

The nature of the second challenge is empirical. While some works deny that Beijing's policies are revisionist, others adopt a similar perspective of the NSS-17 yet disagree on the range of action of Beijing's strategy of change. For example, a first strand of studies speaks of a mounting Chinese challenge to the US. Differently, a second group interprets this competition as strictly limited to the Indo-Pacific. However, only a few researchers explore the revolutionary or, alternatively, the incremental modes of China's revisionism.

To fill these voids, the current article posits that the PRC is pursuing an incremental strategy of change. The hypothesis is tested by tracing its means in order to develop a more accurate theoretical distinction between revolutionary and incremental revisionist strategies. More specifically, the article analyses the modes of China's strategy in the regional security order, which is, in turn, unpacked into five arenas. To clearly bring out the implications of this framework, we compare the trajectory of the PRC with a paradigmatic revolutionary challenger in the Indo-Pacific: Shōwa Japan in the Interwar period (1926–1941).

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 offers an overview of the realist literature on revisionism to highlight its main shortcomings. Section 3 clarifies the research hypothesis, its theoretical framework, and its methodology. Section 4 compares Japanese revisionism in the pre-1941 Shōwa period with China's after 1989. Conclusions discuss the theoretical and empirical findings of the research.

Revisionist

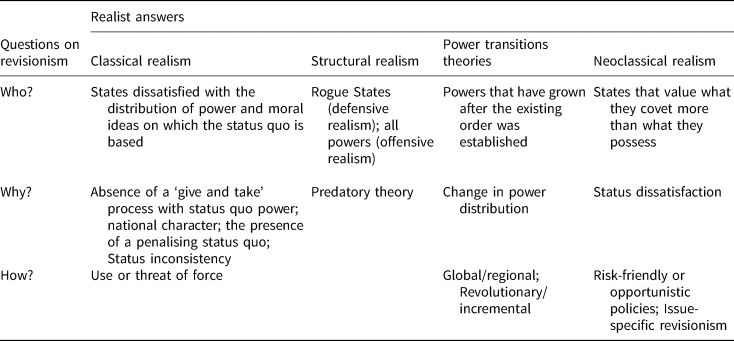

As Andreatta (Reference Andreatta2004) notes, the concept of international orderFootnote 2 implies the existence of a dyadic set of behaviours, that is, those strengthening it and those weakening it. Probably due to the US centrality in IR studies, a wide body of research has focused on the former. By contrast, the study of the latter has been less systematic and at times even ancillary. However, as Table 1 shows, some works of the realist school have tackled the most recurrent theoretical problems on revisionism – in particular, those concerning the actors (who?), its causes (why?), and its modes (how?).

Table 1. Questions on revisionism and the realists' answers

Who?

Most of the works in the field of classical realism were impacted by the shocking revisionist challenge launched by the Third Reich and Shōwa Japan. Such images influenced the first studies that attempted to outline the identity of revisionist states. Carr (Reference Carr1939: 75) speaks of dissatisfied powers as those that are reluctant to adhere to the moral ideals the international order is based on and instead reject them as tools to maintain the satisfied powers' dominance and to mask their ‘interest in the guise of universal interest’. Two subsequent studies have focused on the problem of resources. Morgenthau (Reference Morgenthau1948), on the one hand, explains that imperialist statesFootnote 3 wish for a deep change in the distribution of power. Schuman (Reference Schuman1948), on the other hand, mention the ‘unsatiated’ powers as those feeling humiliated and oppressed by the existing conditions.

The entrance onto the global stage of a new revisionist state, the USSR, inspired the following vast literature on this issue. Although Moscow was partially deprived of the possibility of waging war against its strategic rival (due to the threat of mutually assured destruction), it still proved determined to initiate and sustain wide-range confrontation with Washington. In a precious contribution to a more solid account of revisionism, Wolfers (Reference Wolfers1962) describes revisionists as those countries willing to change the status quo. More specifically, Kissinger (Reference Kissinger1957: 2) labels as ‘revolutionary’ those states that ‘consider the international order or the manner of legitimizing it oppressive’ while, at the same time, ‘nothing can reassure’ them.

The decline of the USSR and the rise of unipolarity after 1991 favoured the emergence of new inquiry about revisionism. Among the structural realists, the defensive ones posit that all the great powers are security-seekers (Waltz, Reference Waltz1979), thus reducing revisionism to an anomaly or overlapping this image with that of ‘rogue States’. By contrast, offensive realists argue that all powers are committed to a permanent revisionist foreign policy (Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2001), as international anarchy pushes to power maximization and thus to perpetual modifications of the status quo. Differently, in the field of power transition theories, Organski and Kugler (Reference Organski and Kugler1980: 19) depict revisionist powers as dissatisfied nations that usually ‘have grown to full power after the existing international order was fully established and the benefits already allocated’. Finally, neoclassical realism brought the revisionist power concept back into the IR debate after the end of the Cold War. In particular, Schweller (Reference Schweller1994: 104–105) concludes that revisionists are power-maximizers who ‘value what they covet more than what they currently possess’.

Why?

The experiences of Nazi Germany and Shōwa Japan influenced the first works of realism also as regards the causes of revisionism. According to Carr (Reference Carr1939), states choose to change the external order when other states profiting the most from it show themselves to be unavailable or unable to undertake/embark on a process of ‘give and take’ with them. Morgenthau (Reference Morgenthau1946: 194), for his part, writes that the ‘ever unstilled desire’ encourages some countries to accumulate power and subvert the status quo. Focusing on the domestic level, Morgenthau explains imperialism as a consequence of the ‘national character’ and ‘national morale’ exasperating states' animus dominandi. By contrast, Schuman (Reference Schuman1948) maintains a systemic-level explanation, arguing that powers strive to change the status quo that penalizes them.

The Soviet case partially escaped such interpretations and encouraged new efforts to understand revisionism. These gained momentum especially after the US defeat in the Vietnam War and the 1973–1975 recession. Wallace (Reference Wallace1973) suggests that revisionism depends on mounting status inconsistency, occurring when states' prestige lags behind their newly formed and still-increasing power. Among power transition theorists, Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1981: 10) contends that emerging powers are often uneasy with the status quo because they did not take part in defining the rules of the game and likely will bid to ‘change the international system’ if and when the ‘expected benefits exceed the expected costs’. This is because the international status quo they face becomes ‘less and less compatible with the shifting distribution of power’ among states (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1988: 601). Similarly, Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1987) interprets change as a fundamental result of geographical variation in the distribution of economic and technological development. States with new resources can convert them into military power and replace the dominant powers.

The emergence of China's and Russia's challenges to the post-Cold War status quo has set the stage for new momentum in the study of the causes of revisionism. Within the neoclassical realist field, Davidson (Reference Davidson2006) and Ward (Reference Ward2017) argue that its origin must be traced in the perceptions of national elites that their state's ambitions are incompatible with the international order. Wohlforth (Reference Wohlforth2009), instead, combines status dissatisfaction with international polarity arguing that the former is more likely to produce revisionist behaviours in the presence of a multipolar system, whose flat hierarchy incentives clashes over the status quo. By contrast, as a structural realist, Shifrinson (Reference Shifrinson2018a) suggests that rising powers adopt predatory policies towards declining rivals – particularly when the latter are simultaneously perceived as unable to assist in opposing other great powers' threats and lack military options to keep the riser in check.

And how?

As for the previous questions on revisionism, classical realism's responses about its modalities were influenced by the Second World War and the opening phase of the Cold War. If Morgenthau (Reference Morgenthau1948) saw in war the most recurrent revisionist tool to supplant an unsatisfactory status quo, Wolfers (Reference Wolfers1962: 125–126) argued that, ‘in quite exceptional cases’ revisionists can accept balanced power if they feel that ‘the established order can be seriously modified’ only by the ‘threat of a force so preponderant that it will overcome the resistance of the opposing side’. The international changes that occurred since the second half of the 1970s – and even more since 1989 – relaunched the demand for a more nuanced definition of the revisionist modes of action. Such definition was supposed to overcome the conventional thinking according to whom revisionists usually trigger a worldwide confrontation with conservative powers – an effort that, often enough, will culminate in a ‘major’ (or ‘hegemonic’) war.Footnote 4 Therefore, new investigations of revisionism have dealt with two different aspects of its modalities: their scope and strategy.

Among the former, some authors have focused on the geographical range of the challenges. Colombo (Reference Colombo2010) explains that the unipolar system is marked by the presence of a regional revisionist power for each subregion in which it can be unpacked. After the Cold War, the US engaged regions' peculiar patterns of cooperation and rivalry, principles of legitimacy, political symbols, and rhetoric. Consequently, the contagion capacity of conflicts also remained territorially confined. Pisciotta (Reference Pisciotta2019), on her part, clearly distinguishes two revisionisms: regional and global. Since dissatisfied states are often rising countries experiencing an increase in relative power, but still lacking proper great power status and capabilities, their conduct is frequently medium-ranged and regionally focused.

In contrast, neoclassical realists tried to grasp the variety of specific issues in which the revisionist challenge occurs. Davidson (Reference Davidson2006) posits that states are concerned with modifying the distribution of five distinct international goods: territory, status, markets, ideology, and institutions. Ward (Reference Ward2017), for his part, suggests that states can be revisionist in two distinct dimensions: they can be dissatisfied either with the international distribution of resources or, rather, with the commonly-accepted international institutions. Lastly, from an unorthodox standpoint, Johnston (Reference Johnston2019) offers a more complicated picture, aggregating international order into eight issue-specific domains.Footnote 5 Revisionist powers could adopt various approaches vis-a-vis different domains, choosing unsupportive or partially supportive postures. As a result, the revisionist challenge may occur in all these domains or in some.

Instead, only a few authors have dealt with the problem of revisionist strategies. Distinctively, Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1981) introduces the distinction between revolutionary and incremental modes of change. All states adopting either one harbour a dissatisfaction with ‘the hierarchy of prestige, the division of territory, and the rules of the system’ (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1981: 14). However, the revolutionary path is taken in the presence of an irrecoverable incompatibility with the pillars of the international order and likely leads to hegemonic wars. On the other hand, the incremental approach occurs ‘within the framework of the existing system’, be they territory changing hands, shifts in alliances and influences, and alterations of the ‘patterns of economic intercourse’ (Ivi, 45).

More recently, Schweller (Reference Schweller1994: 103) distinguishes ‘wolves’, who ‘are willing to take great risks – even if losing the gamble means extinction – to improve their condition’, from ‘jackals’, which ‘tend to be risk-averse and opportunistic’. Finally, Cooley et al. (Reference Cooley, Nexon and Ward2019) advance a disaggregated understanding of revisionism that distinguishes between two distinct dimensions – the international order and the distribution of military capabilities – resulting in three ideal-typical revisionist orientations: reformist powers – expressing satisfaction with the distribution of power but seeking to change other elements of order; positionalist actors – expressing satisfaction with the current order but aiming to shift the distribution of power; and revolutionary ones – waging a full-scale revisionist endeavour.

These seminal works introduced a preliminary distinction between revisionist strategies. However, they did not operationalize their modalities of action and thus maintained a significant gap in the literature.

Who will run the world?

The above-mentioned void causes some difficulties in interpreting China's impressive rise in the post-Cold War era. In particular, a lacerating doubt among IR scholars and practitioners stems from its consecration as a great power and the crisis of the liberal order: who will run the world? (Rose, Reference Rose2019).

Some scholars even deny entirely the PRC's revisionism at least in the consolidated sense of the term. According to some of the most renowned Chinese theorists, Beijing's foreign policy would not fit the Western logic of international interaction, such as the traditional opposition between status quo and revisionist powers or balancing and bandwagoning options (Yan, Reference Yan2011; Zhao, Reference Zhao2019). Some others, even though acknowledging China's discomfort with the US-led order, interpret Chinese revisionism as a consequence of Washington's incapacity to treat Beijing in ways other than as a rival or ‘junior partner’ (Larson and Shevchenko, Reference Larson and Shevchenko2010). China then could still be incorporated into the US-led order through a wise strategy of liberal engagement (Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2011).

Other experts take a somewhat more ominous tone and foresee a gathering storm of a PRC's global challenge to the US-led order. They conclude that Beijing's monumental power accumulation of the last decades encourages it to pursue revisionist goals. Although Jacques (Reference Jacques2009) agrees with those who denounce the common interpretation of China's rise on the basis of Western parameters as parochialist, he confirms that the PRC is spearheading a significant change in world affairs. Allison (Reference Allison2017) contends that the impact of China's ascendance on the US-sponsored global order will constitute the preeminent geostrategic challenge of this era and warns of the risks associated with the so-called Thucydides' trap. Similarly, Layne (Reference Layne2017) and Kagan (Reference Kagan2018) insist that the PRC is challenging the way the US has configured the international order to make a new one to its advantage.

Finally, a third strand of literature claims that China's attitude is revisionist but gauges it as limited by range or strategy. Concerning the range of action, several scholars affirm that its contestation of the liberal order is not global. They hold that Beijing is trying to dictate a new set of norms and behaviours to its neighbours and to restore its historical hegemony over the Indo-Pacific (Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2010; Goh, Reference Goh2019; Mastanduno, Reference Mastanduno2019). This interpretation is echoed in the strategic documents of the last US presidencies. For instance, the Obama Administration denounced China's rise (White House, 2015) and characterized its military modernization as aimed to ‘project power across the greater Asia-Pacific region’ (US Department of Defense, 2016: 68). This stance has been strongly underscored by the Trump Administration. Although it clearly stated that China is undermining ‘American power, influence, and interests’ (White House, 2017: 2), it also reaffirmed that its challenge is primarily focused on gaining ‘Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in the near-term’ (US Department of Defense, 2018: 2).Footnote 6

It must be noted that, even when attention has focused on the PRC's revisionist attitude, few works have researched its strategy of change. Schweller and Pu (Reference Schweller and Pu2011) recognize Chinese revisionism but maintain that a real balance of power has yet to emerge because the PRC must first undermine the US hegemony's legitimacy. Furthermore, Brooks and Wohlforth (Reference Brooks and Wohlforth2015) claim that China is so dissimilar to previous rising states, as the contemporary world is different in ways that hinder its ascent to global power. Feigenbaum (Reference Feigenbaum2017) hints that Beijing is tactically promoting changes within the system and not a systemic change. Lastly, Beckley (Reference Beckley2018) suggests that the US power gap over China still endures, while Shifrinson (Reference Shifrinson2018b) argues that, at worst, the PRC may engage with the US in a limited confrontation or, at best, Beijing may even help Washington against other threat.

To address both the theoretical and empirical shortcomings emerged, the article adopts the seminal distinction of Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1981) between revolutionary and incremental revisionism and posits that China is implementing an incremental strategy of change in the Indo-Pacific in the post-Cold War era (1989–2019). Agreeing with the few works that have contributed to discourse on this topic, the current work assumes that revolutionary revisionism fosters a direct and multi-dimensional confrontation with status quo powers (Ward, Reference Ward2017) and triggers a process of destabilization of the international order which often culminates in a hegemonic war (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1988). This article acknowledges a continuous need for moderation in incremental revisionism, resulting into selective and gradual policies of change towards both the distributive and the normative dimension (Wohlforth, Reference Wohlforth2009; Ward, Reference Ward2017).

To test this hypothesis, the current study investigates the modes of the Chinese revisionist strategy towards the regional security order. This notion refers to how states pursue security in their regions, whether via the maintenance of a suitable distribution of power or through more collective solutions (Morgan, Reference Morgan, Lake and Morgan1997). The choice of exploring this dimension stems from two different considerations. On one side, the need to focus attention on this key sub-order constitutes a well-grounded idea within the realist school. According to it, the stability of any international order is primarily based on power asymmetry and security mechanisms (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1981; Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2001). On the other side, in this domain, the PRC still needs to fill the gap with the US, after having built – as architected by Deng Xiaoping – a ‘state-controlled capitalist economy’ and having supplemented it with growing political influence between the 80s and the 90s (Skylar Mastro, 2019).

In order to conduct an in-depth analysis, the regional security order has been unravelled into five arenas: Military buildup, where a revisionist power is expected to pursue a more distributed military balance (Ward, Reference Ward2017); Military aggressive actions in region, where a revisionist power is expected to take hostile acts against another state (Organski and Kugler, Reference Organski and Kugler1980); Attitude towards the arrangements for regional security, where a revisionist power is expected to challenge the regional institutional setting in the field of security (Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2011); New alliances conflicting with the regional order, where the revisionist power is expected to combine with other ‘sovereign states' for the increase of their own strength – and thus their claims – by reaching ‘formal or informal relationship of security cooperation’ (Walt, Reference Walt1987: 1); New or renewed territorial claims, where a revisionist power is expected to increase its territorial demands due to its ambition to alter the distribution of lands and seas and expand its sphere of influence (Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2001).

The article adopts a historical comparative methodology – based both on primary (strategic and diplomatic documents, international treaties and agreements) and secondary sources (scientific literature, governmental websites, online magazines, datasets) – to trace a clearer distinction between revolutionary and incremental revisionist strategies. Therefore, it compares the PRC's policies towards the regional security order with those of a paradigmatic revolutionary revisionist in the Indo-Pacific, such as Shōwa Japan before WWII (1926–1941).Footnote 7 Following Sartori (Reference Sartori1971), the two cases appear suitable for comparison because they share a crucial condition, that is, being a challenger of the international status quo of their time. The occurrence of this element finds confirmation in the official statements of the two powers. By 1933, indeed, Japan felt that ‘a profound difference of opinions’ – said the government telegram with whom Tokyo left the League of Nations (LoN) – had emerged with the ‘fundamental principles’ of the post-war security order (Japanese Government, 1933: 657). Five years later, the rift was even more explicit when the Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe's address advanced the concept of a ‘New Order in East Asia’ (Konoe, Reference Konoe1939). Beijing, on its side, has shown uneasy with the current regional security order, declaring its willingness to alter it as it is ‘based on Cold War mentality, zero-sum game, stress on force, and unilateralism’ (PRC State Council Information Office, 2017; similar arguments are also made in PRC State Council Information Office, 2019).

A tale of two revisionist powers

The choice of which posture to take towards the regional security order not only informs whether states aim to preserve or revise the status quo in their regions but – and important to this article – also reveals which type of revisionist strategy they have opted for. Applying this framework to the two case studies of pre-1941 Shōwa Japan and post-Cold War China – as done in Table 2 – brings out a tale of two different revisionist powers.

Table 2. Japan's and China's revisionist policies towards the regional security order

Shōwa Japan in the Interwar period (1926–1941)

Still embroiled in the war, Tokyo and Washington signed an agreement to uphold the ‘Open Door’ Policy in China and to respect its territorial integrity and sovereignty. After World War I, Japan contributed to the reshaping of the East Asian order (Ward, Reference Ward2017) and, in exchange, received temporary administration of the Shandong region and the mandate over some former German Pacific islands. As provided by the Covenant, Japan was considered to be a founding member of the LoN,Footnote 8 even while it was greatly disappointed by the absence of a racial equality clause – a circumstance that gradually led to its estrangement from the other conservative powers (Gallicchio, Reference Gallicchio2000). During the 1921–1922 Washington Naval Conference, it convened to maintain the status quo in the region and to consult with the other three powers – the US, the UK, and France.Footnote 9 Under American auspices, Tokyo and PekingFootnote 10 agreed that Chinese sovereignty on Shandong would be restored within 6 months in exchange for compensation and the warranty of Japanese rights and properties in the territory and Manchuria.Footnote 11 As a result of the Conference, Japan signed the Five-Power Treaty, intended to prevent an arms race, to limit naval buildup by allocating different quotas of shipbuilding to the winning powers and to avoid the establishment of military outposts in the Pacific.Footnote 12 Finally, it joined the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1926) to officially reject war as a political instrument (Nish, Reference Nish2002).

The combination of both domestic and systemic factors (Rose, Reference Rose1998) fostered Japan's shift towards a more aggressive stance during the examined period. First, the Japanese political system was founded on parties deeply linked to industrial cartels which, as tensions began to rise, started pushing for more a bellicose position as they could profit from war more than peace (Samuels, Reference Samuels1994). Second, a strong military faction rose to power in pre-WWII Japan and managed to gain a command over many policy areas such as foreign and defence policies sometimes even establishing ‘parallel institutions to supplant the Foreign Ministry's jurisdiction’ (Paine, Reference Paine2017: 87). Third, Japan could benefit from several voids of power around. For instance, China had a weak central authority after the Emperor's abdication and later was strained by the civil war. Also, the post-war Asian security settlement lacked a clear guide as the United Kingdom was distracted by the war recovery process and the mounting threat of Nazi Germany, and the United States was not willing to take the lead (Taliaferro et al., Reference Taliaferro, Ripsman and Lobell2012). Lastly, when France was invaded by Germany, Tokyo felt able to take advantage of Paris' weakness and seize Indochina in September 1940. Within the perimeter of a fragmented international order, the above-mentioned factors exacerbated Japanese revisionist claims and policies.

Regarding military buildup, Japan experienced a dramatic shift towards a more aggressive posture during the Interwar period. The Manchuria campaign, even if not encompassing the whole Army, pushed up military expenditures, which rose even more dramatically in conjunction with the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). As a result, the Japanese defence budget grew on average 25.1% annually. In contrast, the US budget rose by 8.8%, UK by 12.4%, and France by 10.2% in the period before the Second World War broke out (Singer et al., Reference Singer, Bremer, Stuckey and Russett1972). During the 1930s, free from the constraints of naval disarmament commitments, Tokyo ramped up shipbuilding and improved its naval industry to compete and surpass the US as a maritime power in the Indo-Pacific. Washington was the main target to outweigh and against whom the war was imagined, as demonstrated by the 1936 Imperial Navy Operations Plan (Wetzler, Reference Wetzler1998).

With respect to military aggressive actions, Shōwa Japan, after complying with the post-war settlement – as seen in the cession of Shandong to China – opted for an expansionist foreign policy to build a sphere of influence in East Asia and to force the colonialist powers out of the region. Later, Japan continued its meddling into Chinese politics and, as well, its attempts to gain full control over Manchuria (Borsa, Reference Borsa1961). In 1931, while Tokyo was outraged by numerous boycotts by the Chinese people against its assets, it staged a fait accompli to gain a pretext for taking over the contended region. After a bomb exploded on the Japanese South Manchurian railway, the Kanto Army launched a full-scale invasion and Manchuria – as well as part of Inner Mongolia – was seized in a few months. Although Manchukuo retained formal sovereignty, in reality, it was a puppet regime controlled by Tokyo. The Chinese government appealed to the LoN for a condemnation of Japan's actions and obtained a formal reprimand against it both by the League and the US (Nish, Reference Nish2002). In 1932, the Japanese Empire conducted another operation in Shanghai, taking advantage of a local brawl to bomb the city (Paine, Reference Paine2017). In 1937, as a consequence of the Marco Polo bridge incident, Tokyo launched a full-scale invasion of China marching towards Peking (Paine, Reference Paine2012). In 1940, Tokyo decided to cut Nanking's defence supplies, transiting through French Indochina and waging war against France without any formal declaration. The invasion of Indochina lasted for a few days until Vichy France capitulated to Japanese demands; in 1941, Tokyo's control was extended to the French South Indochina (Nish, Reference Nish2002). Lastly, due to the American embargo on oil, Tokyo attacked the US-military base of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, and dragged Washington and London to war. Briefly, for the period analysed herein, the Correlates of War project (Sarkees and Wayman, Reference Sarkees and Wayman2010) acknowledges Japan as the initiator of five inter-state wars and 33 dyadic military interstate disputes when it threatened, displayed, or used military force short of war against another state (Maoz et al., Reference Maoz, Johnson, Kaplan, Ogunkoya and Shreve2018).

The first tear in Japan's attitude towards the arrangements for regional security appeared after the invasion of Manchuria, when China obtained the LoN to condemn Japanese actions. As a result of that event, Tokyo decided to leave the League since ‘an irreconcilable divergence of views as regards to the principles in the establishment of durable peace in the Far East’ had emerged (Nish, Reference Nish2002: 89). After its withdrawal in 1933, the so-called ‘Amo Statement’ outlined the new trajectory of Japan's foreign policy: regional predominance (Hotta, Reference Hotta2007). In 1938, this rift was highlighted in Prime Minister Konoe's address, which advanced the concept of a ‘New Order in East Asia’ (Colegrove, Reference Colegrove1941), an idea that, in 1940, was relabelled as the ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’ (Beasley, Reference Beasley1991). This new order was centred on Japan as a hegemon and encompassed first Northeast Asia and, later, the whole of Asia. By that time, Tokyo was imagining its own ‘centrality within a pan-regional Empire that was to take shape after the war's end’ (Yellen, Reference Yellen2019: 6). This blueprint was essentially an Asian regional imperial design where Japan had to ‘wholeheartedly maintain the Empire's own standpoint and walk the Empire's own path’ (Ivi, 3). To maintain such a grandiose regional control, Japan could not bear heavy constraints on its military power (Nomura, Reference Nomura1935) and thus could not accept to reduce further its naval shipbuilding as the impendent London Naval Conference requested. The ship tonnage ratio established in 1922 and updated in 1930 was then abandoned and Tokyo walked out of the Second London Naval Conference in 1936 (Nish, Reference Nish2002).

The Japanese Empire also made strides in joining new alliances conflicting with the regional order. In 1936, Tokyo signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany and later with Fascist Italy. Although the Pact was not a revisionist military agreement per se, it paved the way for cementing further the security partnership between Tokyo, Rome, and Berlin, as the latter was striving to turn it into a proper military alliance (Galluppi, Reference Galluppi2008). In September 1940, the three powers reached the Tripartite Pact, a military alliance formalizing the German and Italian support of Japan ‘in the establishment of a new order in Greater East Asia’.Footnote 13 Even though they did not directly intervene in the Indo-Pacific, Germany and Italy officially endorsed Japan's revisionism in the region. Furthermore, Tokyo deepened relations with Bangkok, mediating in the Franco-Thai War between 1940 and 1941; it later turned against and defeated Thailand, which was forced to sign a military alliance in 1941 (Paine, Reference Paine2017).

Finally, within this period, Shōwa Japan expanded significantly the perimeter of its territorial claims. Between 1926 and 1941, Tokyo advanced at least 13 territorial requests that were completely new (compared to those during the previous 25 years). Among these are Manchuria, the Amur, the Ussuri River Islands, Inner Mongolia, the Paracel, and the Spratly Islands, parts of British Southeast Asia, the Philippines. Moreover, Japan renewed several territorial claims with renovated vigour after having acquiesced to the post-war settlement during the 1920s (Frederick et al., Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017).

The PRC in the post-Cold War era (1989–2019)

During the Cold War, Washington shaped the order of the Indo-Pacific region following the pattern of a ‘hub-and-spoke system’, that is, a network of bilateral relations with ‘balanced and self-contained friendly regional forces’ (Reagan, Reference Reagan1982: 3–4) such as the Philippines, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.Footnote 14 After 1989, it started supporting also regional multilateral security initiatives (Dian, Reference Dian, Clementi, Dian and Pisciotta2018), such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the East Asia Summit (EAS) (White House, 1993). Similarly, the US has improved its security relations with other actors such as Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, Singapore, India (White House, 2015) and during the Trump Administration has also sponsored a revival of a broad-Asian security arrangement – the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – with Japan, Australia, and India (Pompeo, Reference Pompeo2019).

After acting as a ‘norm-taker’ in the 1990s and 2000s, China is conventionally believed to have stepped up its revisionism during the 2010s. A mixture of domestic and systemic factors influenced such a shift (Rose, Reference Rose1998). First, the monumental development allowed the People's Republic of China to reach the great power status, as a second global economy with a 13% share of the global GDP (World Bank, 2019). Second, Xi Jinping's rise to power in 2012 and the pursuit of his ‘Chinese Dream’ grand vision which drifted Beijing away from Deng Xiaoping's policy of ‘hide and bide’ (Skylar Mastro, 2019). Third, even within a structural perimeter shaped by nuclear deterrence, an incommensurable gap of power with the United States, and Washington's security ties with several Asian regional players, the 2007–2008 global financial crisis still allowed Beijing to publicize the virtues of the ‘Chinese model’ on a global scale and thus represented a window of opportunity (Halper, Reference Halper2010). Fourth, Chinese strategic calculations about being targeted by a new fashion of containment strategies after the Obama Administration proclaimed the ‘Pivot to Asia’ and, even more intensely, after the unilateral turn of the US policies under Trump (which represented both a pressure factor and an opportunity; Medeiros, Reference Medeiros2019). Both Obama and Trump pushed for more coordination with the US regional partners in tackling China's rise and signalled a stronger resolve of shaping Beijing's conduct.

Concerning Chinese military build-up, from 1989 to 2018, China's military budget accounted for an average of 1.9% of its GDPFootnote 15 while that of the US comprised 3.6% of its GDP. China's military budget has augmented significantly from 1989 to 2001Footnote 16 – constituting, on average, 14.2% of its overall government spending (SIPRI, 2019). In the following period, this pace decreased to 8.5% while US military spending accounted for 10.6% of its federal budget. Although the rise of the Chinese military has been constant since 1989, the PRC still falls behind Washington (Brooks and Wohlforth, Reference Brooks and Wohlforth2015). For instance, when it comes to fourth- and fifth-generation jet fighters, Beijing has encountered several technical obstacles and not delivered reliable aircraft.Footnote 17 China's first carrier, Liaoning, is outdated because it is an updated version of an old Soviet Admiral Kuznetsov, while the Shandong is entering service in 2020. However, the latter encountered major technical issues, and rumours are being spread that Beijing could limit the programme to four vessels due to unsustainable costs and technical snags (Stashwick, Reference Stashwick2019). As a result, albeit an impressive improvement since the 1990s, ‘Chinese [military] power diminishes rapidly across even modest distances’ (RAND Project Air Force, 2015: 326) and Chinese maritime rebalancing ‘has not yet displayed the features of a proper global naval projection’ (Dossi, Reference Dossi2014: 164). Facing such limits, Beijing has instead preferred to develop anti-access/area-denial capabilities to gain a military command over its surrounding seas to ‘raise the costs of any US military campaign around China's periphery’ (Shifrinson, Reference Shifrinson2018b: 23) and other vessels such as the Type 055-Renhai class destroyer.

When it comes to military aggressive actions in the Indo-Pacific, Beijing has presented a very low belligerency since 1989. Apart from multilateral operations, China has deployed its People's Liberation Army very few times against other States. In 1995–1996, the PRC fired missiles towards Taiwan and triggered a severe US military response (which compelled it to de-escalate and return to normalcy). In 2017, China confronted India in a military standoff in Doklam, a disputed territory within Himalaya. Notwithstanding the dangerous stalemate, ‘no shots were fired’ (Mendes, Reference Mendes2018: 161) and the crisis was resolved a few weeks later. Therefore, no wars have been fought by China since 1989 (Sarkees and Wayman, Reference Sarkees and Wayman2010). However, in the post-Cold War era, Beijing has embarked on an effort of coercive diplomacy to gain full control of the South China Sea (SCS) without triggering wars. As a result, it ‘is now capable of controlling the SCS in all scenarios short of war with the United States’ (Beech, Reference Beech2018). However, it is important to note that China began its maritime expansion in the SCS way before the end of the Cold War. The first significant military operation dates back to 1974, when Beijing expelled South Vietnamese troops from the Paracel Islands. It was followed by the 1988 Johnson South Reef naval skirmish when the PRC established full control over the reef. Since 1989, due to the deep US security engagement with the Indo-Pacific region and Beijing's sensitivity of triggering tougher containment by its neighbours, China has not conducted any major military operations to take over islands in the Sea, opting for an ‘other-than-war’ approach and a ‘gray-zone’ approach.Footnote 18 Indeed, it has preferred the ‘use of civilian law-enforcement ships to ram the vessels’ of other claimants as well as to block ‘foreign ships from conducting oil and gas exploration’ (Zhang, Reference Zhang2019: 134). Playing this way, it has gained control over islands in the SCS, where it has built military infrastructures and outposts effectively turning the Sea into its military bastion. Accordingly, Chinese record as the initiator of short-of-war disputes is rather high, displaying the occurrence of 52 episodes (Maoz et al., Reference Maoz, Johnson, Kaplan, Ogunkoya and Shreve2018). Among the most renowned cases, there is the 1995 Mischief Reef Incident and the 2012 seizure of Scarborough Shoal which confirm China's predilection of non-escalating options.

The PRC has also shown consistency in its attitude towards the arrangements for regional security. Currently, the task is carried out by institutions created and sustained by US partners and Washington itself (e.g. the ASEAN Regional Forum and Defense Ministers Meeting-Plus as well as the EAS; Ba, Reference Ba, Pekkanen, Ravenhill and Foot2014). After the Cold War, ASEAN stood up against Beijing in 1992 issuing a statement on the SCS status and, likewise, later condemned the 1995 Chinese seizure of Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands. Concerning the EAS, China was originally enthusiastic about the idea of a pan-Asian security architecture, but later changed its mind when Japan and Singapore pushed for including India and Australia and after the United States joined EAS meetings in 2010 and 2011 (Cha, Reference Cha, Pekkanen, Ravenhill and Foot2014: 742). Facing a worsening institutional environment during the 2010s, China has advanced the New Asian Security Concept (NASC), an architecture proposal for regional security and the only proposal of a Chinese-designed security institution. Initially mentioned by Premier Li Keqiang during the 2013 East Asia Summit and later relaunched by Xi Jinping in 2014, the NASC is meant to let the ‘people of Asia run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia, and uphold the security of Asia’ (Xi, Reference Xi2014: 392). This proposal has been interpreted as challenging the security order backed by the US in Asia (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015: 574). The NASC proposal is inspired by the belief that security should be based not on ‘outmoded Cold War alliances and military blocs’ (Larson and Shevchenko, Reference Larson and Shevchenko2010: 82). This framework is then rooted in China's antipathy for military alliances which, according to its diplomats and top officials, are ‘unnecessary vestiges of the Cold War’ (Shambaugh, Reference Shambaugh2004: 70). However, NASC was followed by confusing rhetoric and behaviour and no breakthroughs have been achieved since its proposal (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015). Two years later, it was de facto shelved. The Chinese White Papers of 2017 and 2019 made no mention of the 2014 NASC (PRC State Council Information Office, 2017).

With respect to the blueprints of new alliances conflicting with the regional order, China has shown self-restraint. Its only alliance remains with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea via the 1961 Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty, which was renewed automatically in 2001.Footnote 19 By backing Pyongyang, the PRC indirectly challenges part of the US-led security order in the Indo-Pacific, as North Korea is a violator of the non-proliferation regime and a threat for US allies in the region (e.g. South Korea and Japan). Consistent with its long-lasting stance on alliances, China has desisted from advancing new proposals of mutual defence since the end of the Cold War. A particular mention must be made of the China–Russia security partnership in the Indo-Pacific which has been regarded in the past as a ‘relationship of convenience’ (Lo, Reference Lo2008: 54). Today's China–Russia security cooperation seems, though, to have moved beyond the ‘convenience phase’ and towards deeper integration and coordination, both bilaterally and within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Even if they apparently are ‘on the verge’ of an alliance, there is still much ambivalence and ambiguity especially regarding Russian position on China's territorial ambitions (Korolev, Reference Korolev2018). Moreover, Beijing has been wary of describing the nature and purpose of its ties with Moscow, carefully avoiding the terms ‘allies’, ‘alliance’, ‘defence’, and referring to it as a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era’ (Kania and Woods, Reference Kania and Woods2019: 20).

With regard to new or renewed territorial claims, China shows a long-standing coherence in its contestations. Today, the PRC's territorial disputes concern the status of Taiwan, the sovereignty over the SCS islets as well as over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) (Fravel, Reference Fravel, Pekkanen, Ravenhill and Foot2014), the border disagreement with India. All of them are Cold War's inheritances. For instance, Taipei's Republic of China historically occupies a central place in China's thinking (Xi, Reference Xi2019) and, as a post-WWII heritage, cannot be considered a new or renewed claim. However, threatening may Xi's words sound, his recent speeches echo those delivered by all previous Chinese leaders (Johnston, Reference Johnston2013). Moreover, when it comes to actual threats, Beijing has not ever used military force against Taipei since 1995–1996. It refrained from employing military coercion also in late 2016 and early 2017, when President-elect Trump phoned Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen in the first official contact since 1979 to announce an upgrade in the US-ROC relationship. In the ECS and the SCS, things are different. Regarding the ECS, Beijing has held a grudge since at least 1971, when Washington returned to Tokyo the territories it had administered after WWII. Among those handed back to Japan were the Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands (considered part of the Ryukyu archipelago). China raised complaints because the islands were seized by the Japanese Empire with an ‘unequal treaty’Footnote 20 and demanded, instead, their cession (Pugliese and Insisa, Reference Pugliese and Insisa2017). Since 1971, the Senkakus have been officially ruled by Tokyo, while Beijing's voice has gone unheard. However, China ‘downplayed its claims [in the ECS] and sought to delay any resolution’ of the issue until 2010 (Fravel, Reference Fravel2016: 24). Conversely, in 2012, China reasserted its demands with new vigour, driving the dispute to a diplomatic escalation. Following the Japanese government's purchase of three of the islands, China unleashed a campaign of regular patrols within 12 nautical miles from the islands with its maritime militia to signal its commitment to the defence of the status quo. Nonetheless, since 2013, China and Japan have proved quite capable of managing such tensions: the dispute seems at present to have stabilized (Monteiro, Reference Monteiro2014). In the SCS, China has expanded its frontier; today it wields tight military control over most of the Sea. Yet even while Beijing currently boasts an increasing command over the SCS, its claims in the area are not new. As far back as the 1950s, it strived to gain mastery over the Paracels but later was overtaken by the Philippines and Vietnam. Only in 1974 and again in 1988 was China able to fight back, seizing some of the Vietnamese Paracels; in 1994–1995, China expelled the Philippines from Mischief Reef in the Spratlys using non-military means.

Conclusions

The article was motivated by the twofold need of providing a well-nuanced categorization of revisionism and, as well, understanding China's posture towards the US-led order.

The literature review revealed that the modes of revisionism still remain poorly studied. Gilpin's distinction between revolutionary and incremental revisionist states has not been further developed. While it is generally assumed that a revolutionary power challenges the international order in all its components, little is known of the incrementalists' policies except for their tendency towards gradual and selective challenges.

Thus, the first contribution of this article is theoretical. It diachronically compares an alleged incremental revisionist – the PRC in the post-Cold War era – with a paradigmatic case of revolutionary revisionism in the Indo-Pacific – as Shōwa Japan in the Interwar period – by analysing their policies towards regional security order. Although the comparison necessarily requires to be expanded to a wider number of cases and dimensions, this method proved to be effective in bringing out a preliminary description of the different modes of change implemented by ‘revolutionaries’ and ‘incrementalists’.

About military build-up, revolutionaries are expected to allocate a larger share of their government budget on defence than the status quo power/s. On the contrary, incrementalists will increase their spending without exceeding that of the conservative one/s. Concerning military aggressive actions, the revolutionary stance implies a recurring proclivity to the use or menace of violence against other actors, while states pursuing incremental strategies are more likely to employ means below the threshold of war. When it comes to the attitude towards the regional arrangements for security, revolutionaries denounce the main existing institutions and are expected to advance new conflicting fora. By contrast, incrementalists adopt a critical standpoint towards the institutions within which they choose to remain. Furthermore, revolutionary revisionists are more prone to establish subverting military alliances, while incremental revisionists refrain from creating military alliances explicitly targeting the – global or regional – status quo. Finally, new territories are more likely to be openly claimed by revolutionaries, which also tend to vindicate with renewed vigour previous demands. Conversely, incrementalists are wary of advancing new claims but may be prone to raise voices in demanding long-requested territories.

The second contribution of the article stems from empirical analysis. It highlighted that Chinese regional revisionism in each arena sticks to an incremental pattern of change as it displays the following features. First, the PRC is pursuing an upgrade of its Army but has fallen behind Washington both from a quantitative (i.e. in terms of military expenditures and shares of defence within the government budget) and a qualitative perspective (i.e. it has not been able to acquire US-level military technologies). Secondly, China has not yet shown a high level of belligerency since 1989. It also has limited employment of the PLA, preferring coercive means that fall below the threshold of war. In the Indo-Pacific, Beijing has further chosen to join and remain in the institutions for regional security, even if it has adopted a more sceptical and critical standpoint towards them. In 2014, it put forward a new security architecture proposal which, however, was dismissed shortly after. Likewise, it has not suggested or created any new alliance in the region even if it is increasingly leaning towards Russia. Lastly, China has indeed pursued with renewed vigour its territorial claims but has made no new ones compared to the Cold War era.

To conclude, this work is aware that it has provided a small contribution to a very broad and challenging field of study. However, it represents only a first step towards a more comprehensive understanding of the explored phenomenon. A further approach could be to adopt a neoclassical realist perspective in order to investigate the causes of the PRC's choice of an incremental – rather than revolutionary – strategy of change. In fact, the domestic political and economic concerns seem to play a crucial role in shaping both Beijing's strategic thinking and policies.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alessandro Colombo (University of Milan) for the preliminary feedback on the topic and Scott Morgenstern (University of Pittsburgh) for reviewing an early draft of the article.