Introduction

The classical approach to the study of results in European Parliament (EP) elections comes from second-order elections (SOEs) theory (Reif and Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980). In a nutshell, the theory postulates that EP elections are less important than national legislative elections, which are first-order as they decide what matters most within each political system – who governs the country. As such, EP elections are used both by parties and voters to obtain desired outcomes for national governance – even though that is not what these elections are about. As we will discuss later, at the individual level, this implies that the same determinants of vote choice for national first-order elections (FOEs) should be relevant in influencing choices in the SOE, such as EP elections.

Differently from the second-order model, the so-called ‘Europe matters’ (Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2007) approach argues that EP elections are not of secondary relevance, but elections that are fought about Europe and with a specific issue content, distinct from that of FOEs.

The core of this article is an individual-level assessment of which of these two scenarios has characterized the results of 2019 Italian EP elections. The Italian case is, in this respect, particularly interesting, given the extraordinary level of aggregate-level volatility recorded between the 2018 general elections and the 2019 EP elections. Just over a year after an incredibly volatile national legislative election – which exceptionally was the second in a row of that kind (see Chiaramonte et al., Reference Chiaramonte, Emanuele, Maggini and Paparo2018), amazing numbers of Italian voters again changed their vote – almost 40%. In comparison with the recent previous parliamentary election (held in March 2018), in May 2019 the League doubled its votes and its governmental ally (M5S) halved its result (Landini and Paparo, Reference Landini, Paparo, De Sio, Franklin and Russo2019). Mainstream parties also had opposite trends, with the left-wing Democratic Party gaining and the right-wing Forza Italia losing votes. Furthermore, these electoral variations took place in a context characterized by a relatively low level of ideological structuring, in terms of both voters' attitudes and parties' issue stances and strategic issue emphases (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Maggini and Paparo2020). It is also worth noting that part of the recent successes of parties such as the League and the M5S in Italy (at the time of European elections, both in government) are clearly related to an emphasis on issues related to European integration. For all these reasons, the Italian case appears particularly interesting to test the second-order vs. ‘Europe matters’ model.

In order to perform such an investigation, we develop an innovative issue-voting approach, which is aimed at investigating (a) the issue-content distinctiveness (if any) of EP elections, compared to national, FOEs; (b) the relative impact of European and domestic issues on vote choice of voters in EP elections vs. national elections – leading to an overall assessment of the extent to which ‘Europe mattered’ in the 2019 EP election, on top of how much it already matters in national, FOEs.

To address the research questions of this article, we will employ an original survey dataset collected by the CISE (Italian Centre for Electoral Studies) immediately before the 2019 EP elections. This dataset includes 30 issues, both positional and valence, and both domestic and European Union (EU)-related. As a result, we are able to unpack generic, summary pro-contra EU integration attitudes into issue attitudes that are differentiated across different dimensions related to the EU, providing a richer and more complex measurement of EU-related attitudes.

The article is structured as follows. In the next two sections, we review the classic SOEs model with its individual-level implications; we discuss an alternative ‘Europe matters’ explanatory model based on the distinct relevance of the European dimension of conflict and arena; and we advance two rival hypotheses derived by these two models. We then present the data we employ to empirically test our hypotheses, and we detail our specific methodological choices. Next, we report empirical evidence and discuss the implications of our findings. Conclusions follow.

The second-order model of EP elections

EP elections have traditionally been considered as second-order national elections, that is, elections of secondary importance with respect to first-order general elections. The concept of SOEs was first introduced and popularized by Reif and Schmitt (Reference Reif and Schmitt1980). Looking at the first EP elections held in 1979, they showed that, in a system of multilevel governance, elections held at various levels of governance present a substantially different nature. FOEs are perceived as politically more relevant, because these elections establish who will hold power and, more generally, the political orientation of a country. SOEs, on the other hand, are perceived by voters as less relevant, because less is at stake: such elections do not profoundly affect the political orientations of a country, as well as the actual management of political power. More generally, SOEs are held in the shadow of general elections, in fact reflecting the dynamics of domestic political conflict (Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011). If domestic political conflict is not significantly structured by issues related to Europe (as it was generally the case in years before the global financial crisis of 2008–12), then EP elections would have little European content despite their objective of electing members of the EP.

The theoretical model of the SOE provides three general expectations about EP election results at the aggregate level (Reif and Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005). The first expectation concerns the level of turnout. If EP elections are really of a second order, electoral participation in these elections should be systematically lower than in general elections, as a sign of a relatively lower interest for this kind of electoral competition. To be true, lower levels of participation in EP elections have been interpreted in different ways. On the one hand – and according to the second-order model – low turnout is intended as clearly pointing to a low level of public interest in this kind of election; on the other hand, it has been sometimes referred to as symptomatic of anti-European feelings (see e.g. Blondel et al., Reference Blondel, Sinnott and Svensson1998). However, several analyses (Schmitt and Mannheimer, Reference Schmitt and Mannheimer1991; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005) have shown that lower levels of electoral participation in EP elections cannot be traced to feelings of hostility towards the EU or interpreted as a crisis of legitimacy of the EU.

A second expectation that derives from the second-order theory concerns the dynamics of electoral competition between governing parties and opposition parties. Given that relatively less is at stake in EP elections compared to general elections, voters may use EP elections to express an overall assessment of the government. In particular, voters might use this channel to express dissatisfaction with the performance of the current national government (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005). From this point of view, the second-order model expectation is that in EP elections governing parties will perform worse compared to previous FOEs; on the contrary, opposition parties should achieve relatively better results. These electoral dynamics are essentially driven by two mechanisms: on the one hand, voters who had voted for governing parties in general elections may decide to remove their support for these parties and opt for opposition parties (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005); on the other hand, voters of governing parties (even if satisfied with the performance of the government) might abstain more than voters of opposition parties. We know, for example, that differential mobilization among voters of governing and opposition parties is the most relevant factor leading to government electoral losses in EP elections (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005).

In turn, the adoption of the second-order approach to make sense of EP election results has allowed to also borrow important theoretical insights on SOEs that were developed before and independently from EP elections. This is especially the case for ‘electoral-cycle’ effects. Specifically, EP elections are grafted within the electoral cycle of national FOEs. On the basis of the electoral-cycle approach (Tufte, Reference Tufte1975; Stimson, Reference Stimson1976), the success of governing parties follows a cyclical trend: in a first phase (the so-called ‘honeymoon’), these parties enjoy broad and robust support from the electorate; at a second stage, this support declines, even in a radical way, only to recover in the final phase of the legislature. Taking into account the dynamics of the electoral cycle, the losses of governing parties and the success of the opposition parties in EP elections should take place in an ‘orderly’ fashion (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2005). In other words, the moment when elections for the EP are held with respect to the national electoral cycle is a fundamental fact to be taken into consideration.

A further aspect of differentiation between FOEs and SOEs concerns the relations between large and small parties. As already highlighted above, the stakes in SOEs are relatively lower than in FOEs and it is therefore appropriate to expect voters to vote less strategically. In the case of FOEs, voters are expected to vote mainly ‘with the head’ and perform some kind of strategic voting, by not only taking into account their sympathy for party goals, but also the likelihood that the party, due to its relative size within the legislature, will be able to have an impact in terms of policymaking (although it may not represent the voter's first preference). These strategic considerations lose relevance in the context of SOEs, where voters may prefer to vote ‘with the heart’, thus choosing the party they sincerely prefer and voting even for parties that might be relatively small and not influential in the first-order arena. Therefore, smaller parties should get relatively better electoral performances in SOEs.Footnote 1

Reassessing the second-order model

Second-order expectations have been variously tested and empirically confirmed over time (Reif and Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980; Reif, Reference Reif1984; Schmitt and Mannheimer, Reference Schmitt and Mannheimer1991; Van der Eijk et al., Reference Van der Eijk, Franklin, Oppenhuis, Van der Eijk and Franklin1996; Marsh, Reference Marsh1998; Schmitt and Van der Eijk, Reference Schmitt, Van der Eijk, Van der Brug and Van der Eijk2007; Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011). However, there has been no lack of criticisms, and different scholars have attempted to complement and refine the theoretical framework introduced by Reif and Schmitt.

Individual-level implications of the second-order model

One of the main critical aspects of the second-order approach concerns its aggregate-level nature (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Sanz and Braun2008; Hobolt and Wittrock, Reference Hobolt and Wittrock2011). As Schmitt et al. (Reference Schmitt, Sanz and Braun2008) themselves recognize, the main problem of the second-order model is that it does not develop a theory of voting at the individual level. While this is true in general, it however does not imply that the theory does not produce any argument about voters' electoral behaviour at the individual level, and indeed several scholars have empirically tested individual-level implications of the second-order model (see e.g. Boomgaarden et al., Reference Boomgaarden, Johann and Kritzinger2016; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Sanz, Braun and Teperoglou2020).Footnote 2 Let us see several.

The first individual-level implication of the second-order model is that, net of the role of the European arena and issues on national elections (i.e. Europeanization of national politics), EP elections should have little or nothing to do with the European dimension (Marsh and Franklin, Reference Marsh, Franklin, Van der Eijk and Franklin1996; Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011). This implies no EU effects on EP elections in a context in which national elections are independent of EU-related issues.

Extending the same logic to a different context, in which national FOEs are (at least partly) played on EU issues, the consequence would be that EP elections would acquire more European content as a direct result. In this respect, important applications of SOE theory (Van der Eijk and Franklin, Reference Van der Eijk and Franklin1996) clearly rest on the assumption that any EU content driving EP elections would indicate a differentiation with national elections only as long as national elections do not contain any EU-related discussion yet (see also more explicitly Franklin and Hobolt, Reference Franklin, Hobolt, Richardson and Mazey2015; Nielsen and Franklin, Reference Nielsen and Franklin2017). As long as EP elections are not about Europe more than national elections, this would still be in line with classical SOEs thinking – FOEs and SOEs determined by the same factors (Franklin and Hobolt, Reference Franklin, Hobolt, Richardson and Mazey2015).

Basically, our claim is that SOEs are SOEs as long as they do not present any distinctively specific (policy) content. From this perspective, we think that the classic SOE model could then easily and productively be relatedFootnote 3 to the concept of normal vote (Converse, Reference Converse, Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1966). In short, the idea is that party identification determines the voter's ‘normal vote’ towards the party of identification, that is, the voter's general tendency to vote for (candidates of) the party she identifies with, compatibly with occasional deviations that might arise from specific factors (such as e.g. the actual candidates, or other short-term factors) that are distinctive of a particular election. Coming to the specific case of EP elections, we then argue that – in order to be able to assess whether EP elections can be still classified as SOEs – we need to look at deviations from normal voting observed in EP elections. If such deviations (if present) are characterized by specific political content, it will be difficult to claim that such elections are exclusively SOEs; alternatively, if instead they do not appear driven by any clear political factor, this would indicate the persistence of their second-order nature.

Regarding the potential utility of the classic ‘normal-vote’ theory for the second-order model, it is interesting to observe that such theory could be also compatible with some classical aggregated findings of the SOE literature. For instance, the decline in turnout in SOEs could derive from the fact that, since stakes are lower, mobilization will be lower, and thus electoral participation would become mostly driven by party identification through normal vote.

A second individual-level implication of the second-order model concerns the interplay of strategic (‘with the head’) and sincere (‘with the heart’) voting. The negative performance of governing parties can be attributed to some (relatively sophisticated) strategic voting in SOEs, with voters feeling free to voice their dissatisfaction with the work of governing parties, knowing that this might change the behaviour of governing parties but not change the government itself. But, on the other hand, smaller parties are expected to be rewarded because voters could vote sincerely without relevant consequences. These last two propositions have been seen as at least partially in contradiction: indeed, voters can vote strategically, punishing a governing party for its performance or trying to signal their preferences on certain issues; but, if they do so, they cannot vote sincerely, choosing the party they really prefer (Hobolt and Wittrock, Reference Hobolt and Wittrock2011). Several scholars have in fact argued that both mechanisms (i.e. strategic and sincere voting) are in place at the individual level in SOEs (e.g. Camatarri and Zucchini, Reference Camatarri and Zucchini2019). In particular, Schmitt et al. (Reference Schmitt, Sanz, Braun and Teperoglou2020) found empirical evidence that ‘mobilisation and sincere and strategic factors are all playing an important role in our understanding of differential abstention and defection’ in SOEs (p.15). In this regard, we argue that the increase in vote shares for small parties could be also looked at from a normal vote perspective. Indeed, this approach appears adequate to account for the higher relevance of sincere voting in SOEs (compared to FOEs). Basically, voters choose strategically in FOEs when they are informed and motivated to not waste the vote (which might account for deviations from normal vote in FOEs), while they should rely more on their party ID (and thus their normal vote) in SOEs, if the latter do not have an important stake and a specific content.

The ‘Europe matters’ model

Alternatively to the second-order model, a different interpretation of the nature of the European electoral competition was provided by a different line of studies. This line argues that EP elections are not secondary elections, but elections with their own identity, in which political conflict over Europe is more relevant than in national elections. Several scholars (Hix and Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2007; Clark and Rohrschneider, Reference Clark and Rohrschneider2009; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Spoon and Tilley2009) have argued that the traditional left–right axis has an explanatory capacity for electoral outcomes especially in competitions for the renewal of national parliaments, while the general pro/anti-EU dimension would have a key role above all in the European arena. Other studies (e.g. Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Spoon and Tilley2009), instead, have shown how the punishment of governing parties in EP elections can be linked to different positions as regards the process of European integration. Voters could in fact punish governing parties (generally more Europhiles than their electorates) precisely because of a discrepancy of opinions about how much integrated the EU should be. Finally, there is a certain degree of overlap between the two levels of governance, given that European issues could also be relevant in the domestic arena and have weight in FOEs (Hobolt and Wittrock, Reference Hobolt and Wittrock2011). In other words, according to this alternative approach – generally labelled as ‘Europe matters’ – second-order theory (although still important to understand EP electoral results) offers only a limited perspective on this kind of elections, overlooking the specific importance of a truly European political dimension in influencing voters' choices in EP elections (more than it does in national elections).

However, we note that this new perspective might ignore the fact that, even within the second-order model, EP elections could have acquired a European dimension to the same extent that national politics did the same, as we have pointed out above. Thus, this increase in relevance of EU issues on national elections would not alter the prominence of FOEs within each national political system: while perhaps now containing EU content, they would still have higher stakes. On the contrary, the ‘Europe matters’ approach would be confirmed in the case in which deviations from normal voting behaviour in EP elections were in fact determined by distinctive issues or other political factors (typically expected to relate to the EU dimension), net, of course, of the reciprocal contamination of the two electoral arenas.

Against this backdrop, we can formulate two rival hypotheses. A first hypothesis is derived from the second-order approach. According to this approach, we expect that:

H1: Deviations from normal vote in the EP elections do not present any specific political content, distinct from that characterizing deviations in the general election.

As a result, EP elections would be simply manifestations of normal voting not adopted in national elections, or echo the same issues determining deviations from normal vote at the national elections.

A second, rival hypothesis is derived from the ‘Europe matters’ approach. In order to confirm the ‘Europe matters’ hypothesis, we expect that:

H2: Deviations from normal vote in EP elections present certain specific policy content, distinct from that characterizing deviations in the general election, which involves EU institutions in either framing or decision responsibility.

If this hypothesis is confirmed, our results would lend support to the idea that EP electoral results at the aggregate level should be interpreted as a result of an electoral competition in which voters care about specific issues (possibly European in their nature) more than they do for national elections. In a nutshell, the idea is that EP elections might have a distinctive policy content (specifically related to the EU) that makes these elections something fundamentally different from national elections.

Research design

Levels and dimensions of EU voting

To assess the distinctive European dimension of EP elections, we need to address some operational questions that are not trivial. A first crucial aspect to be taken into consideration is that European issues are relevant at least at two different levels (Weber Reference Weber2009): one that has to do with the integration process (how much integrated the EU should be); and one which has instead to do with policy content (i.e. policies decided at the EU level). In the past, the relevance of the policy content dimension was only marginally addressed, since the Union's policies were in any case decided at the intergovernmental level. Nevertheless, things have been changing in the last decades (especially since the coming into force of the Lisbon treaty). With the deepening of the integration process, the policy areas on which responsibility now lies within the EU have expanded; and the powers of the EP in the decision-making process of the EU have increased considerably, with the EP being now a key legislative body of the Union. In this context, it is plausible to think that, as the relevance of the EP increases, also EP elections might no longer be perceived as inconsequential or significantly less relevant than FOEs.

So far, individual-level studies assessing the second-order nature of EP elections have resorted to the proximity of voters to parties on the left/right and pro/anti-European dimensions of political conflict, based on the argument that the left/right dimension should structure electoral competition at the domestic level, whereas positions on EU integration should be much more relevant in SOEs. We argue instead that one should take into account both levels of relevance of Europe, and this is why in this study we go beyond the formal dichotomy between left/right and pro/anti-European integration, also addressing the substantive content of specific European policies decided at the EU level.

By doing so, we propose to assess the appropriateness and relative predictive ability of the ‘Europe matters’ vs. second-order framework by leveraging an issue voting approach. What indeed will matter is not necessarily whether voters recognize (and reward or punish) parties because of their willingness to promote more or less EU integration, but rather because of the specific issue goals these parties support (and are likely to achieve) on issues that are decided at the domestic vs. at the European level. In other words, if Europe really matters, voters should, at least partially, assess parties in terms of EU-related issues: those issues whose prevalent framing in the public debate involves EU competencies.

In so doing, we borrow from the issue-yield framework (De Sio and Weber, Reference De Sio and Weber2014), which – especially in its most recent developments (D'Alimonte et al., Reference D'Alimonte, De Sio and Franklin2020) – provides tools that enable a comprehensive analysis of issue politics generalized across valence and positional issues, in fact putting ‘all issues on a par’ (ibidem, 529) and providing a parsimonious and symmetric attitude measurement strategy for both kinds of issues. The generalization strategy provided by these authors (then implemented in the ICCP scheme – see below) rests on two steps: first, the definition of both positional and valence issues in terms of issue goals, with positional issues being defined by two rival goals and valence issues instead defined by a single, shared goal; second, the conceptualization of party-voter affinity (on each issue goal) in terms of party credibility in achieving a desired goal. Party credibility for achieving an issue goal (be it widely shared, or clearly divisive) is thus introduced as a generalization of the concept of party competence (traditionally used for valence issues) into a notion that is applicable also to the controversial goals that define positional issues (ibidem), which could hardly be associated with the technical-resonating notion of competence. As a result, goal credibility emerges as a more general concept that, unlike its intrinsically unmatchable positional and valence equivalents (respectively proximity and competence), captures voter-party affinity in a comparable, unified fashion, leading to the possibility of studying all issues comprehensively and homogenously in the same model. Finally, in terms of vote choice from the perspective of the individual voter, the theoretical model that is implied is that the voter enters the electoral arena with a set of goals she would like to be achieved (some divisive, some shared), and that she will attempt to select the party that she considers most credible for achieving these goals.

In terms of the pragmatic necessities of our article, the use of these notions of issue goals and party goal credibility has a clear advantage: it allows to get a comparable voter-party affinity measure for both positional and valence issues, thus allowing to study them simultaneously in the same model. As a result, this approach enables the construction of a comprehensive issue-voting model that includes not only the effect of general positional dimensions (the general pro/anti-EU and left–right dimensions mostly used to assess the ‘Europe matters’ vs. second-order framework), but also the more specific and nuanced issue content that might reveal the distinctiveness of EP elections compared to general elections. This approach requires survey data with rich issue content, covering both domestic and EU issues, but it provides in exchange a clearer and more accurate strategy for assessing any allegedly increased importance of Europe.

The data

Our analyses rely on the data provided by an original CAWI survey designed by the CISE (Italian Centre for Electoral Studies) and administered by Demetra srl in Italy in the month preceding the EP elections held on 26 May 2019. The survey relies on the data collection scheme developed for the ICCP (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, Emanuele, Maggini, Paparo, Angelucci and D'Alimonte2019; De Sio and Lachat, Reference De Sio and Lachat2020), albeit not being part of that comparative project (which covers general elections). Our original dataset includes information on individual-level issue attitudes on a large number (30) of domestic and European issues, both positional and valence, which have been selected by country experts based on their relevance throughout the campaign, and framed in terms of their dominant framing in the Italian public debate. In particular, we classified as EU-related only those issues whose framing explicitly refers to the EU and/or directly involve the EU in the decision-making process.Footnote 4 This structure of the dataset represents a distinctive feature of our study: not only because of the very large number of issues included, but also because such large number allowed us to include a meaningful number of both domestic issues and EU-related issues.

Being based on the ICCP scheme, the dataset allows us to analyse both positional and valence issues simultaneously. Issue attitudes are measured with reference to issue goals that can be employed to conceptualize positional and valence issues in a homogenous way. Valence issues are represented by a single shared goal (e.g. ‘boost economic growth’). On these consensual issues, respondents are explicitly asked to rate party credibility in achieving that goal.Footnote 5 Conversely, positional goals first require the respondent to side with one of the two rival goals entailed by the positional nature of the issue (e.g. ‘immigration should be further limited’ vs. ‘immigration should not be further limited’), and then to indicate all the parties that are credible to achieve the selected goal. As a result, consistent measurement is obtained for party credibility on any issue goal (either related to positional or valence issues), thus allowing homogeneous data analysis (D'Alimonte et al., Reference D'Alimonte, De Sio and Franklin2020).

A second distinctive feature of our study refers to our dependent variables. We use consistent items capturing vote preferences both in national and EP elections. Our survey data contain independent measures of vote intentions for these two distinct voting choices. This allows a rigorous operationalization and testing of the second-order and ‘Europe matters’ models, through a thorough comparison of the determinants of vote choice in the two sorts of elections.

In particular, we are interested in understanding which issues (and whether domestic or European) dominate the overall voting behaviour patterns in the two electoral arenas, thus perhaps leading individuals to vote for different parties in the two elections. As a result, for each respondent, for both national and EP elections, we focused on the construction of a dichotomous variable, indicating whether the respondent deviates from normal vote in that (EP or general) election. To that end, we needed to preliminarily detect respondents' normal vote. We did so by looking at the party receiving the highest PTV (propensity-to-vote) score. In particular, respondents were asked to state their PTV independently for all relevant Italian parties; we considered as normal voters of a party all respondents that assigned to that party their highest PTV score in comparison to all other parties (725 out of 1000).Footnote 6 Only these normal-vote respondents will be included in the theory testing empirical analyses investigating the issue determinants of defections from normal vote in national and EP elections.

This particular operationalization of normal vote requires a specific discussion. In short, we claim that expressing a higher PTV for a party, compared to all others, is a manifestation of a distinct party preference (disconnected from a specific election) that might precisely indicate normal voting, that is, the vote choice that would be expressed by the respondent in the absence of any election-specific, short-term factors. Our choice in this direction is reassured by two elements. First, recent research has convincingly shown that it is in fact possible to fruitfully construct a valid measure of party identification precisely from the overall configuration of PTVs across different parties, in particular – relying on normal vote theory – by looking at the highest one compared to all others (Paparo and De Sio, Reference Paparo and De Sio2017; Paparo et al., Reference Paparo, De Sio and Brady2020). Secondly, we offer further validation for our measurement choice by employing our dataset to assess whether the determinants of our measure are compatible with it being an indicator of a ‘normal vote’ attitude, that is, if they recall the factors that structurally drive voters towards such behaviour as theorized by classic party identification theory. If this operationalization is really able to capture a normal vote preference, most of its variance should be then captured by long-term predictors of vote choice (such as, in particular, left–right general orientation and, especially, party identification itself); while short-term factors (current government popularity or issues of the day) should provide little predictive power.

The results of this validation analysis are reported in Table 1, which includes two alternative logistic regression models predicting our measure of normal vote.Footnote 7 In the leftmost model, only long-term indicators are included, while the rightmost model adds short-term factors. We can safely claim that our measurement choice appears corroborated by the empirical evidence. Only long-term factors, and, in particular, ideological orientation and – even more so – party identification, account for almost 40% of variance in our measure of normal vote. The addition of numerous short-term indicators, namely 30 issues and satisfaction with the government, does make ideology non-significant (quite predictably, as the left–right dimension is broken down into its various issue components), but increases the overall predictive power of the model only to a modest extent, considered the very large number of predictors added. Finally, also in this second model, party identification emerges, by far, as the most relevant predictor of the outcome. All in all, we believe that this evidence, paired with the aforementioned literature contribution, provides robust validation for our measurement choice for assessing normal vote preference.

Table 1. Predictors of normal vote preference, operationalized as highest-PTV

Notes: P-values in parentheses; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pseudo R 2 is McFadden. The adjusted count represents the proportional reduction in error for correctly classified cases, compared to a null model where all cases are assigned to the largest category.

As anticipated, for those respondents having a normal vote preference, we built two similar but separate indicators for defections in legislative and EP elections. Namely, for deviations from normal vote in EP elections, the dependent variable is constructed out of a standard voting intention survey item, asking respondents the party they will vote in the (then upcoming) May 2019 EP elections. Coherently, for defections from normal vote in national elections, we have employed the standard survey item asking about vote choice in case of immediate national legislative elections.

Moving to our independent variables, we modelled them as follows. Party-voter affinity variables (e.g. respondent-assessed party credibility for achieving a certain goal) have been retained only with reference to the normal-vote party for each respondent. Thus, for each respondent, we register how the normal-vote party is assessed by R on different issues. For variables that are not party-specific (namely, age, gender, education), we employ them interacted with a categorical variable indicating which the normal-vote party is.

We test our hypotheses by relying on a modelling strategy designed to be robust to model specification, a concern which is particularly sensitive given the large number of predictors involved. We proceed in three steps. First, separately for each issue, we assess its effect on our two dependent variables (i.e. defections at both the EP and general elections) controlling for the standard set of sociodemographic variables; secondly, we perform a multivariate regression model with all the 30 issues included in our dataset, plus the same controls; thirdly, we use a selection model analysis (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator, hereafter LASSO) (Frank and Friedman, Reference Frank and Friedman1993; Tibshirani, Reference Tibshirani1996) to further investigate which, among all the 30 issues considered in this study, are most likely to explain defections in the two arenas (see below for more details).

We now need to discuss how exactly we operationalize respondent issue attitudes in order to assess the impact of the latter in different kinds of elections. For positional issues, the respondent had to first select one of two rival goals; and then, for the selected goal, she had to tick all parties that she deemed credible for achieving that goal. Therefore, respondent-assessed party goal credibility has – for the normal-vote party of each respondent – a value of 1 if the party is deemed credible for achieving the goal selected by the respondent; otherwise it has a value of 0.Footnote 8 It is worth noting that, for positional issues, the same variable contains credibility information for either of the two rival goals.Footnote 9 As a result, a generic ‘normal-vote party credibility on R's preferred goal’ is recorded, allowing us to later gauge the effect of such party issue credibility on our dependent variables – irrespective of the side chosen by the respondent.

For valence issues, the strategy we adopt to assess the impact of domestic and European issues on vote choice is the same as above, with one qualification. In contrast to positional issues, valence issues imply only one, shared goal. We thus omit the first step (selection of one of two rival goals), and simply operationalize these valence issues by looking at normal-vote party credibility on a single goal, assumed as consensual. Thus, the result is a variable that is fully homogeneous with the one calculated for positional issues, and the effects of both types of variables can also be directly compared (D'Alimonte et al., Reference D'Alimonte, De Sio and Franklin2020).

Findings

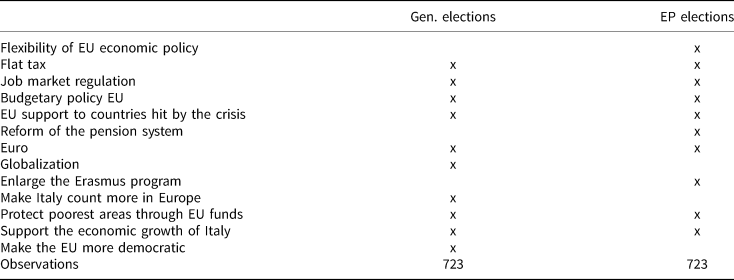

Table 2 reports the logit coefficients derived from a set of 30 logistic regressions, with each individually including one of the 30 issues considered in this study, plus controls. In both arenas, coefficients for any single issue are negative and highly significant, showing that when parties are deemed to be credible in achieving a desired issue goal, the likelihood for defection decreases in both general and European elections. In fact, deeming the party credible to achieve a goal provides an anchor to not quit the normally preferred party in the election at hand. All this considered, a first approach to understand which issues have been most relevant in preventing defections is to look at the predictive power of each single-issue model. Net of the effect of sociodemographic variables, we find that defections at the EU elections are better prevented by party credibility in relation to: protection of the poorest areas of the country by means of EU funds (Pseudo R 2 = 0.24); economic flexibility of the EU (Pseudo R 2 = 0.23); EU budgetary policy (Pseudo R 2 = 0.22); economic support to countries hardly affected by the economic crisis, support to the Italian economic growth and the flat tax (all three with Pseudo R 2 = 0.21). As for defections at general elections, the best fit – in terms of predictive power – is found for: flat tax, economic support to countries hardly affected by the economic crisis, protection for the poorest areas of the country by means of EU funds (all Pseudo R 2 = 0.21) and budgetary policy of the EU (Pseudo R 2 = 0.20). Interestingly enough, defections at EP elections are best predicted by models which include European issues (with flat tax being the only exception), whereas defections at general elections seem to be best predicted by a combination of national and European issues, a clue of the increased Europeanization of national politics.

Table 2. Logistic regression analyses

Notes: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. DVs: defections at general and European elections. The columns under the common label ‘Single issues’ report the logit coefficients (b) and Pseudo R 2 for a set of regression analyses using as independent variable any single issue individually (together with control variables). The columns under the common label ‘Full models’ report the results of two logistic regressions predicting respectively defections at general and EP elections and using the whole set of 30 issues as independent variables (together with controls). In bold coefficients for variables showing the highest Pseudo R2 in ‘Single issues’ models, those statistically significant in ‘Full models’. Complete models, also reporting the estimates of standard errors, are available in the Appendix. Pseudo R 2 is McFadden. The adjusted count represents the proportional reduction in error for correctly classified cases, compared to a null model where all cases are assigned to the largest category.

Clearly, these single-issue models do not allow yet to detect whether and to what extent the two electoral arenas are characterized by an issue-based distinctiveness, which is required to test our hypotheses. To assess whether defections at the general and EP elections are driven (and indeed prevented) by specific issue content, we rely on a multivariate logistic regression including as predictors party credibilities for all the 30 issues simultaneously. Here, patterns of statistical significance as for which issues prevent defections in the two elections provide a first test of our hypotheses. Concerning general elections, defections are mostly prevented by party credibility on the flat tax and the protection of the poorest areas of the country by means of EU funds. In other words, a combination of domestic and European issues contributes significantly to prevent defections in this arena.

As for EP elections, we find again that a combination of national and European issues has a significant ability to prevent defections, but with a prevalence of genuinely European issues. In particular, three out of four significant issues are European in their nature and these are the credibilities related to: flexibility of EU economic policy; enlargement of the Erasmus program; protection of the poorest areas of the country through EU funds. The only significant domestic issue relates to the reform of the pension system (‘Quota 100’). We stress, however, that such policy domain has had ties with the EU dimension in its framing for at least 30 years in Italy, while numerous reform plans were approved or proposed with no success. Most importantly, and decisively for our hypothesis testing, we do find that, among the statistically significant issues which anchor voters to their normal vote in EP elections, there is only one issue that is shared with the model for general elections: party credibility in protecting the poorest areas of the country by means of EU funds.

This means that H1 has to be rejected, while H2 is corroborated. In fact, our findings indicate that, beside an undoubtable contamination of the two electoral arenas, EP elections are indeed characterized by specific issue contents, which are significant predictors of electoral behaviour in such a type of elections. Furthermore, to reiterate what we have already observed, net of the reciprocal contamination of the two arenas, voters are anchored to their normal vote in European elections in prevalence by EU-based anchoring issues.

Although the aforementioned fully specified models already reveal specific issue content for each of the two electoral arenas, they still suffer from problems of overspecification and collinearity. Indeed, credibilities for a party on different issues are – not surprisingly – highly correlated with one another and, when they are included together in a regression model, they may produce biased estimations. To mitigate problems related to multicollinearity, we have reduced the complexity of the models, through a model selection procedure based on LASSO regularized regression (Frank and Friedman, Reference Frank and Friedman1993; Tibshirani, Reference Tibshirani1996), aiming to identify the best predictors among the 30 issue credibilities.Footnote 10

The issue selection resulting from the LASSO regression (Table 3) is in general consistent with the findings of the fully specified multivariate model, albeit producing a richer and more nuanced picture of the relevant anchoring issues. In terms of our hypotheses, again, H1 has to be rejected, while H2 is empirically confirmed.

Table 3. LASSO logistic regression

Notes: For both defections at the general and EP elections, selection solutions are obtained for 50 lambdas. For defections at general elections the lambda selected by EBIC is 14.17; for defections at EP elections the lambda selected by EBIC is 13.1.

Not surprisingly, we find a large reciprocal contamination of the two electoral arenas, with seven issues emerging as significantly preventing defections both in general and EP elections. Among these, we find issues that are both domestic (flat tax; support of economic growth of Italy; job market regulation) and genuinely European (budgetary policy of the EU; economic support to countries affected by the economic crisis; the Euro; the protection of the poorest areas of the country through EU funds). However, the specific, distinctive issue content of EP elections is confirmed, which disproves H1. Further, crucially to verify H2, the distinctive issue content of EP elections relates to two European issues (economic flexibility of the EU and the Erasmus program) and one domestic issue (the reform of the pension system) with significant EU-related aspects in its national framing – as we have mentioned above. Most importantly, these are the three issues that emerge as distinctively and significantly preventing defections at EP elections also in the fully specified model.

Bringing together all these pieces of evidence, it is clear from our investigation that: (a) the choice to defect from a party in the EP election is characterized by specific issue content, as specific (and distinctive) issues emerge as able to anchor EP vote to normal vote – in other words, defections in EP elections are not simply due to non-political factors (e.g. lower turnout by respondents with lower education) but they are shaped by issue attitudes; (b) these issue attitudes also clearly include (and in a prominent role) EU-related issues. If it is true that European issues already matter in national FOEs, to the extent that these same issues have now entered the national competition (thus conditioning both national and EP vote), it is also true that EU-related issues – alongside domestic issues – exert an additional, distinctive effect (i.e. beyond the contamination common to the national and the European arenas) on the choice to defect from the normal-vote party in EP elections.

On this basis, we can ultimately reject H1 (SOE hypothesis), and affirm the distinctiveness of EP voting, alongside the presence of EU-related issues within it – the two elements required by H2 to verify the ‘Europe matters’ hypothesis. Regarding the first element, this is clearly confirmed. EP voting would not be distinctive if, for example, EP defections (or their prevention) would be only predicted by socio-demographic factors. Such defections instead clearly present issue content, so that there is an issue distinctiveness of these elections. These findings could still be compatible with a fully second-order explanation, if these issues would be only related to national politics – for example, issues entirely managed by the national government – or fully analogous to the issues affecting general elections. However, our data show that this is not the case. Among the issues relevant for EP defections, we find several that are clearly related to the EU and not relevant for vote choice in general elections. From this, we derive a general interpretation of our empirical findings: Europe distinctively matters in EP elections, motivating voters to turn out and express a party preference. At the same time, we even found empirical confirmation for a distinctive importance of some domestic issues in EP elections, which indeed also provides support for the second-order model – aside, however, an undoubtable presence of effects of EU-related issues.

Discussion

Our analysis aimed at offering a contribution to the theoretical elaboration of individual-level mechanisms related to existing models (so far mostly formulated and tested at the aggregate level) of EP elections, namely the second-order vs. ‘Europe matters’ models. We confronted this challenge from a specific vantage point. First, by leveraging an especially issue-rich, individual-level dataset that allowed a much more nuanced conceptualization of EU-related issues and attitudes. This allowed us to move beyond the simple, classic EU integration item, toward a rich, comprehensive selection of real-world issues related to EU institutions and EU-affected policy areas, compared and contrasted with genuinely domestic issues. Secondly, our empirical strategy was tested in an election that presented a specific challenge – analysing the behaviour of voters in reaction to what was set up one year earlier in Italy as the first entirely ‘populist’ government in a large Western European country.

Our findings present several points of interest. First of all, our analytic strategy appears promising in its ability to account for a large portion of the variance in voting behaviour. Despite the presence of a very high volatility (at least in terms of vote shares) between the 2018 national and the 2019 EP election, it is reassuring to learn that such volatility is not due to idiosyncratic or ephemeral factors that go beyond our theoretical tools, but rather corresponds to a combination of long-term factors and specific patterns of differential issue credibility across different parties, which can indeed be understood according to their ability to prevent (or to further encourage) voter defection at EP elections. Curiously, this is a mix of economic, cultural and institutional issues, providing a more plausible picture, compared to Italian media portraits suggesting a dominant immigration issue carried forward by the League's Matteo Salvini.

So much for the substantive specifics of the 2019 result in Italy. In terms of the more general theoretical and methodological meaning of our contribution, we have two main points to make. On the one hand, this article demonstrates a novel research strategy for assessing second-order vs. ‘Europe matters’ models in EP voting by controlling for the importance that EU-related issues have acquired also in national elections (and also by leveraging a rich set of issues). On the other hand, by drawing a connection with party identification and normal vote theory, we introduce a strategy for assessing EP voting that goes beyond the simple comparison with general elections, providing a third indicator acting as a benchmark for both EP and general elections. The results of this analysis provide a plausible picture that sees a clearly distinctive importance of EU-related issues, alongside still present second-order effects.

The question that is left open is the generalizability of these findings. Indeed, the first ‘populist’ government in a large Western European country invested significantly on a stark confrontation with Brussels in the months that preceded the 2019 EP election, making publicly visible and salient those confrontations and negotiations that usually take place behind closed doors in the European Council. As a result, it is perhaps not surprising that EU-related issues emerged as relevant for voting behaviour. What would happen instead in other countries whose governments invested much less on such issues, or perhaps even tried to downplay these issues when raised by challenger parties? This remains an open question, albeit one that – we argue – should be confronted with issue-equipped datasets that are at least as rich as in our design, and perhaps with an analysis strategy that borrows our emphasis on patterns of vote deviations rather than simply on vote choices.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of this article was presented at the conference ‘Europa al voto. Tra sfida nazionalista ed europeista’ organized by the Italian Society for Electoral Studies (SISE), ITANES and the SISP Standing Group POPE at the University of Genoa, 4–5 July 2019.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2020.21.