INTRODUCTION

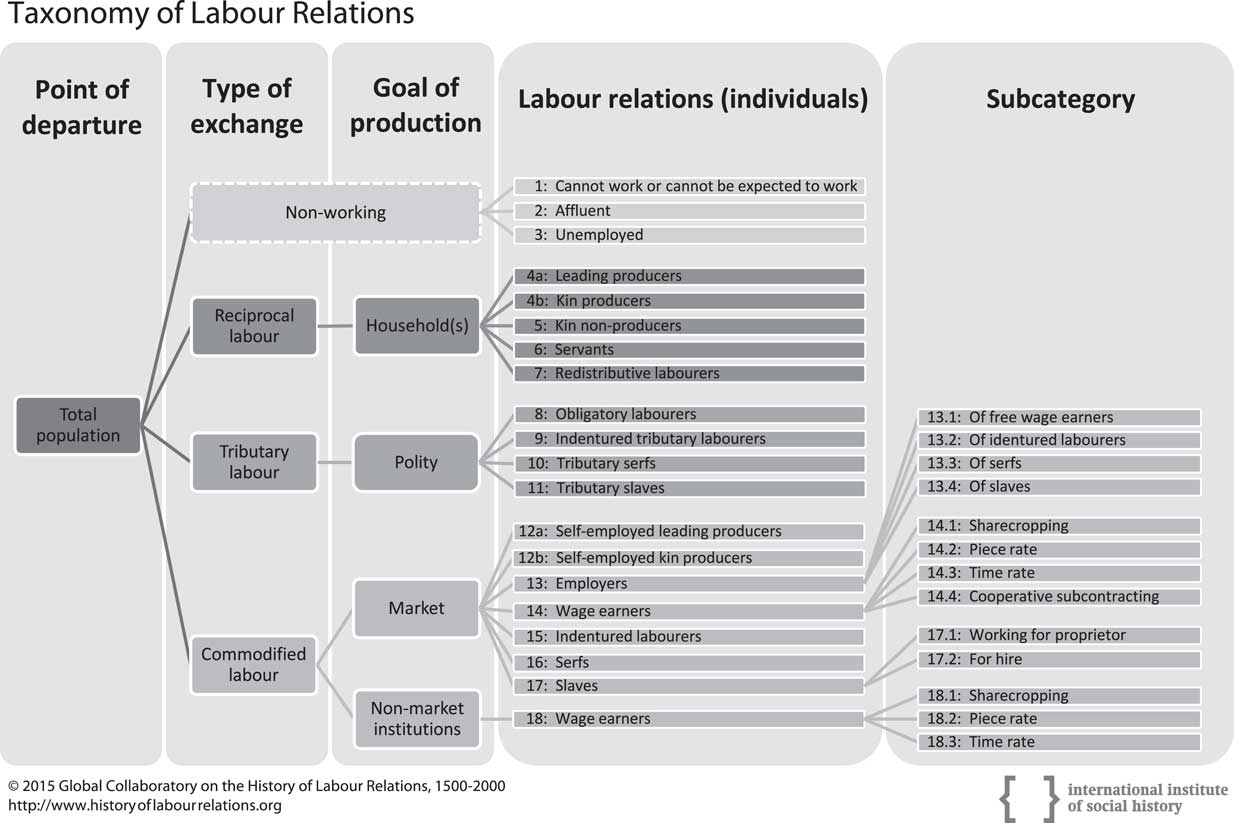

This volume owes its existence to the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, a long-standing effort uniting labour historians across the globe in an attempt to trace and explain historical shifts in labour relations over a timeframe roughly coinciding with the rise and subsequent development of capitalism (1500–2000).Footnote 1 Labour relations are understood as the full range of vertical and horizontal social relations under which work is performed, starting from a basic subdivision in society between those who are not expected or who are unable to work (the young, the elderly, and the infirm) as well as the unemployed, and those who work, whether part-time or full-time, outside the home or at home, in self-employment, or as wage earners, in slavery, or as employers.Footnote 2 The first phase of this project (2007–2012) consisted of data mining and brought together data on labour relations on the basis of a shared taxonomy (see the appendix to this introduction for the taxonomy and the definitions of the various labour relations) in five benchmark years (1500, 1650, 1800, 1900, 2000) for a wide range of countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas.Footnote 3

The second phase of the project seeks explanations for shifts in labour relations as well as for the possible patterns observed therein. Causes and consequences of shifts in labour relations are explored by looking in depth at possible explanatory factors in a series of dedicated workshops in order to subsequently combine the insights this produces into proper multi-causal explanations. The central question that interests us here is under what conditions shifts take place, how these impacted the way work was valued and compensated, and what the consequences were for the level of inequality in society.Footnote 4

The first workshop in this series examined the role of the state in effecting shifts in labour relations; the results are reported in the present Special Issue.Footnote 5 The reason that we started our investigation based on the state is that the state emerged from our fact finding as the single most visible factor inducing shifts in labour relations, such as the emergence of the second serfdom in seventeenth-century Muscovy, the rise of military labour through mercenary armies and navies, conquest and subjugation, colonial exploitation, and the mass resort to convict labour and forced labour in twentieth-century totalitarian societies. Other examples of state intervention in labour relations are the abolition of slavery, regulation of child and women’s labour, labour legislation, and, in a more recent past, the introduction of welfare states exempting part of the population from the need to work in order to support oneself. The articles in this volume look at shifts in labour relations in a wide diversity of periods and places, ranging from the sixteenth-century silver mines of Potosí in the Andes to late twentieth-century Sweden, and from seventeenth-century Dzungharia to early twentieth-century colonial Mozambique.

In this Special Issue, we use the term “state”, a widely accepted term or concept in the various debates on state formation, even though the term “polity” more adequately captures the range of possible manifestations of state power, including early states, empires, and, at the meso and micro levels (including neighbourhoods and their governments), regional authorities and city states. Our use of the term “state” should not be read as a sign of an uncritical and straightforward identification of the state as a single-level actor, with one single and coherent policy. State-society relations, the role of supranational polities as well as the role of social agency in shaping, resisting, deflecting, and modifying state action, are taken on board wherever possible in the articles in this volume, also leaving room for unintended consequences of state policies.

STATE FORMATION: RESOURCE EXTRACTION AND GOVERNANCE

The principal analytical framework for our findings is provided by the scholarship on state formation. Our understanding of states is both organizational and instrumental. To start with, a definition of the organizational element: states consist of institutions and personnel that determine political relations radiating to and from a centre. They cover a territorially demarcated area over which they exercise power to make binding rules and, in doing so, they are backed up by organized physical force.Footnote 6 The more instrumental definition of states is more difficult to give, since definitions of state functions are often determined by political theories and thus can be contradictory; moreover, state functions differ over time and space. However, an indispensable activity of any state is the extraction of the resources, in cash, kind, or manpower, needed to exercise power and determine political relations. Centralizing power, enforcing a monopoly on the use of coercion, and extracting the resources allowing rulers to achieve these first two goals are the basic steps in state formation. In addition, state formation can also include the development of infrastructure, education, and social security systems. However, the occurrence of these forms of state formation varies widely over time and space. Before we address a reasoned selection of the extensive literature on state formation, it is necessary to identify the relevance of the different aspects of state formation for labour relations, so we can connect these to the shifts in labour relations that can be historically observed.

Firstly, it is necessary to distinguish between the state as a direct actor or participant, carrying out tasks deemed essential for its functioning, and the state as an arbiter, redistributor, or regulator. As a direct actor, the state influences labour relations as an employer – initially, above all, as a military employer – as well as in its capacity as a conqueror, effecting existing and possibly imposing new labour relations on conquered societies. For want of a better term, this also includes the “employment” of forced labour and conscript labour. As an arbiter, redistributor, or regulator, the state acts to steer other social forces in directions deemed to be beneficial either for the functioning of the state itself, or to political and ideological agendas espoused by the state. These two capacities of the state are not strictly separated, but intertwined, and have existed side by side throughout trajectories of state formation, although, over time, the importance of the state as an arbiter and regulator has undeniably increased.

It has been argued in response to our categorization that if the state participates in the labour market, it is not, and cannot be, a purely impartial arbiter or redistributor, because as an employer it must live up to the obligations and regulations it imposes, including, for example, possible restrictions on the use of forced or tributary labour, and this can affect policymaking. Also, states can be dominated by and act in the interests of certain social groups or classes and will therefore often tend to take sides.Footnote 7 Some of the authors of this Special Issue stress this point more strongly than others.

In constructing the analytical framework for this volume, and the workshop that preceded it, we were inspired by the work of Charles Tilly on early modern European state-formation processes. In his seminal work on the relationship between war-making and state-building,Footnote 8 he argues that European rulers, locked in geopolitical competition, were continuously confronted with the need to raise the means and extract the resources to wage their increasingly costly wars. This constituted the main driving force behind the processes of state formation as they played out in early modern Europe. Rulers needed to mobilize more and more resources to fund their wars and built increasingly elaborate extraction apparatuses, which eventually developed into the states we know today.

Tilly distinguished between three principal trajectories along this path, and it was particularly this aspect of his work that inspired us, because it fitted so well with the patterns observed in the articles presented in this Special Issue. Even though Tilly’s ideas have been criticized for being modelled too narrowly on the experience of early modern Europe, we have found them to be a very useful heuristic instrument in all times and places to analyse the methods used by states to extract resources and to determine labour relations. Firstly, there was the capital-intensive trajectory, followed by early city states such as Venice and, later, by the Dutch Republic, which could easily tap the significant commercial wealth generated within the territories under their rule, and relied on taxation to fill their coffers and recruit labour for their armies and navies.Footnote 9 On the opposite side of the spectrum were the northern and eastern European states, such as Sweden and Russia, further away from important trade routes and commercial wealth and therefore with little choice other than to rely on coercion and the forceful extraction of resources to raise the means for war, developing bulky state apparatuses in the process. In contrast to Venice and the Dutch Republic, labour was less easily recruited on the market, and this caused a tendency to rely on tributary labour. In the long run, however, the most successful proved to be the capitalized-coercion trajectory, which combined the forceful extraction of resources with the incorporation of capitalists in the state structure through the granting of privileges, thereby enabling the ruler to constantly tap this wealth to enlarge state capacity. Such states, like England and France, won out because they could amass taxes on a much larger scale than city states like Venice and use these financial means to build large armies and navies, bringing them out on top in the perpetual interstate competition over power.

Crucial in the process of state formation in Europe, Tilly argues, was that states needed legitimacy in order to place fiscal and other obligations on the population, and this resulted in a constant process of bargaining with the population over the extraction of resources. In this process, European states granted rights and privileges and made concessions to individuals and groups of citizens who controlled the resources to be extracted. As states attempted to ever broaden their tax base, this eventually lay at the root of the democratization processes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Critics of Tilly’s interpretation scheme point to its limitation both in time and in space. To start with the first, Michael Mann states that Tilly’s theory is too military driven and thus applies mainly to earlier periods, when the principal activity of many states was indeed war-making.Footnote 10 In the second half of the nineteenth and in the twentieth century, most European states, at least internally, expanded civilian activities, by building infrastructures, national education systems, and welfare systems. All these are state-formation processes that cannot be explained in terms of war-making. Here, according to Mann, other aspects of civil society play a role, such as religion, secular ideologies, and other sets of norms and values he calls ideological sources of power.Footnote 11 This is also where Marcel van der Linden’s suggestion to add culture to capital and coercion as causes of state formation comes in.Footnote 12 As we will see in the articles in the second half of this volume, which focus on the state as arbiter and moderator, ideology comes to the fore as a major motivational force in state action, more explicitly so than where states act primarily in their capacities as conqueror or employer.

Secondly, Tilly’s work has also come in for criticism because it insufficiently accounts for non-European patterns of state formation, in particular in parts of the world where war-making was less important for state formation.Footnote 13 Literature focusing on state-society relations as part of state formation in non-Western countries shows how societies could often challenge processes of state formation and – in the case of former colonies – transformation. Pre-colonial forms of state formation were crucial in these processes.Footnote 14 As regards taxation, it has been pointed out that not all forms of taxation are conducive to democratization or the granting of rights. When states can raise sufficient resources by taxing lightly, for example, as the Chinese state did throughout many centuries of its history, they can actually get away with no or very little bargaining at all.Footnote 15 Also, Tilly’s interpretation was based too much on the experience of early national states and later nation states, ignoring the experience of other state formations, such as empires, the importance of which in world history has recently been underlined.Footnote 16 Indeed, recent work by Roy Bin Wong has revealed a significantly different modus operandi of the late imperial Chinese state in resource extraction and governance, which poignantly underlines the fact that state formation in Asia is still an understudied phenomenon, notwithstanding a growing body of literature that sets the stage both on colonial and post-colonial Asian states as well as on Asian states that were never colonized.Footnote 17

The global aspect of state formation and state activities forms part of recent literature on the different capacities and modalities of states in fostering economic development, and in particular in creating the institutions conducive to economic development.Footnote 18 Of particular interest to us here is the attention paid to this issue within the framework of the Great Divergence debate on the origins of the differential development of Asia and Europe. Crucially, the early modern Chinese state appears to have operated on fundamentally different principles from its European counterparts in its political economy and economic policies.Footnote 19 Whereas European states concentrated their efforts on stimulating economic development, creating the conditions, often monopolies, for merchants and capitalists to generate wealth that could subsequently be taxed, the late imperial Chinese state aimed in many ways to create a level playing field, acting against concentrations of wealth and power and relying on a fiscal policy of relatively light taxation of as large a number of peasant producers as possible.Footnote 20

THE STATE AND LABOUR RELATIONS

Considering labour relations, our approach starts with the state in its capacity as a direct participant, as conqueror, or employer facing the question how to mobilize and allocate the labour power and resources required to carry out the civil and military tasks deemed essential for its functioning. In our view, this involves a choice between two principal options: (1) to impose taxes in money or kind and to use the resources accumulated in this way to pay people to perform the tasks to be fulfilled, whether military, civil, or auxiliary (i.e. capital); or (2) to mobilize the people, resources, and equipment to carry out these tasks by imposing direct labour obligations (i.e. coercion). States can choose to follow either option with their own people and institutions, or can decide to outsource these activities and co-opt other people, groups of people, or even states, to carry out these tasks, granting them privileges, autonomy within larger state structures, powers of supervision, or subjugation over others, for example. In this introduction, we rely on the dichotomy between capital and coercion to bring some order to the wide variety of policies deployed by states to carry out their core tasks. Of course, the two options are not mutually exclusive, and practically all states rely, to some extent, on both of these options, but the mix between them varies both among states and over time. Moreover, larger states, and particularly empires, can rely on coercion in one area, or in relation to certain groups, on taxation in another, and opt to outsource and co-opt these tasks in one area and act themselves in another.Footnote 21

In sum, the research agenda for the contributions to this Special Issue was to provide an analysis of empirical cases of shifts in labour relations where the state intervened in one way or another. The following sections contain the findings of the individual articles and contributions to the workshop. They show how the three options of acquisition and disposal of labour power were handled by states across the globe, in different times and different settings. At the end of this introduction, we will provide an interpretation of these cases in the framework of the explanatory matrix of state activities and the typology of the roles of states as conquerors, employers, and arbiters.

THE STATE AS CONQUEROR: THE CHOICE BETWEEN COERCION AND CAPITAL

Due to their monopoly on the means of violence, states as direct participants of the labour market have strong means of determining labour relations. This applies particularly to imperial states in the phases of conquest, when they strive to enlarge their territory. Yet, not all states choose coercion to recruit labour. The articles and contributions considered in this introduction look at China from the Song to the Qing (tenth to nineteenth centuries) as well as Russia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the Spanish colonial empire from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. By contrast, Venice, as a city state, is an excellent example of the option to recruit by capital and co-optation.

In her article “Tributary Labour Relations in China During the Ming-Qing Transition (Seventeenth to Eighteenth Centuries)”, Christine Moll-Murata focuses on the Chinese state in the period of transition from the Ming (1368–1644) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). The conquest of the empire by the Manchu changed the “physiology” of the Chinese state in several important respects. The Manchu dynasty brought along its own system of social-military organization based on banners – groups of hereditary military households comprising both warriors and their families and servants. Before the conquest of China these banners had been engaged in self-sufficient farming in peacetime, but were paid by the state in times of war. After the conquest of the empire, they protected the court and key strategic towns and were freed from all other obligations but its military ones, for which they were permanently remunerated in silver and grain. This system combined elements of coercion (labour service) and capital (remuneration), not only in goods, but also in privileges, and a great deal of autonomy was granted to the bannermen. Apart from relying on the banners, the Qing dynasty also deployed a professional army of paid Han Chinese soldiers – the Green Standard Army. This reliance on capital, rather than coercion in military organization, marked a departure from the corvée principles on which Ming-era military mobilization had been based, and Moll-Murata attributes this change also to the influx of silver during that period.

At the workshop, these findings were placed in a long-term perspective in a paper by William Guanglin Liu.Footnote 22 Looking at military wages and remuneration over a period from the early Song dynasty (960–1279) to the Ming (1368–1644), Liu presented a picture of a Chinese state switching back and forth between reliance on capital and coercion in its task of footing and maintaining an army. Before the Song, military organization relied on land-based, hereditary military households, but monetization and commercialization during the Tang-Song transition in the tenth century resulted in the introduction of indirect taxation and a shift towards military recruitment based on direct employment and remuneration in cash. This system was reversed again, however, due to the impact of the Mongol conquest (1200–1279), which put military organization back on a demonetized footing under the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). This practice was continued under the subsequent Ming dynasty, based on military settlements of soldier-farmers, who fulfilled military duties and contributed grain to state reserves. The main cause of this change was the end of the commercialization of the Song period, which left the early Ming dynasty unable to mobilize a mercenary army as their predecessors had done, and they therefore chose to rely on the hereditary military household system, which could function independently of monetized state finance. In conjunction, Guanglin Liu’s and Moll-Murata’s findings draw our attention to the degree of commercialization and particularly monetization of an economy as a crucial variable in determining outcomes of the capital-coercion choice that states face.

This is also powerfully illustrated by Dmitry Khitrov’s article, “Tributary Labour in the Russian Empire in the Eighteenth Century: Factors in Development”. The late eighteenth-century system of tributary labour obligations in the Russian empire formed an essential element of the system of military mobilization on which the Russian state had based its impressive territorial expansion from the sixteenth century onwards. Against the larger background of serfdom in the Russian heartland, Khitrov focuses on two groups performing tributary labour duties in the southern and eastern border provinces of the Russian state. These were the military service class, who performed military duties in exchange for allotments of land, and state peasants assigned to work in industries that were of strategic military significance for the Russian state.

The military service class consisted of various military settlers, Cossacks, and co-opted non-Russian groups, who had in common that, in exchange for land, they carried military service obligations in the southern and eastern border areas of Russian expansion. The tributary labour obligations of the state peasants assigned to certain industries were also an essentially non-monetary system of labour mobilization. The two cases studied by Khitrov therefore provide further evidence of what has been described as Russia’s quintessential model of war-making and war-related resource mobilization that developed in a low-capital environment, relying on non-monetary instruments such as conscription, military settlement, grain deliveries, and land allotments in exchange for service.Footnote 23

The Russian case compares in an interesting way with that of the city state of Venice, a typical example of the capital-intensive trajectories of state formation. As Andrea Caracausi showed in his paper presented at the workshop, Venice relied largely on monetary means of mobilizing military labour for its fleet, primarily by paying patricians to actually carry out the operation of the ships, but also in recruiting the skilled labour for the Arsenal, where its galleys were built. Shipbuilders at the Arsenal were assured of a wage, even if there was no work, thus achieving the same effect of avoiding the market in the supply of strategic labour as in Russia, but by monetary, rather than coercive means. It should be noted, though, that for actually rowing the galleys the Venetian fleet also made ample use of the forced labour of prisoners of war, which serves to underscore that practically all states, to some extent, combine coercion and capital in achieving their aims.Footnote 24

The articles by Raquel Gil Montero and Paula Zagalsky, “Colonial Organization of Mine Labour in Charcas (Present-Day Bolivia) and Its Consequences (Sixteenth to the Seventeenth Centuries)”, and Rossana Barragán Romano, “Dynamics of Continuity and Change: Shifts in Labour Relations in the Potosí Mines (1680–1812)”, focus on labour relations in the Andean silver mines, discovered by the Spanish conquerors in the 1540s. When Viceroy Toledo was in office (1569–1581) he re-established and drastically changed a pre-Hispanic tributary system, the mita. Toledo transformed this system into a state-organized and enforced draft of coerced labour to ensure a continuous supply of labour to the Potosí silver mines. Communities of indigenous people had to send tributaries as mitayos to the mines. Mita work was done in weekly turns. Having done their turn, the mitayos could spend their “free” time as hired workers in the mines (as mingas). Having returned home after a period of corvée, they worked under reciprocal labour relations on their own land or that of their communities, thus combining various types of labour relations over the year. Some of the natives preferred to work for Spanish landowners, rather than be subjected to the extremely harsh labour obligations of the mita. The royal officials accepted this if the landowners paid the tribute that the mitayos owed the state. Thus, the coercion-intensive trajectory of the Spanish colonial state also relied on the co-optation of local authorities and Spanish individuals and on outsourcing part of the extractive activities to them.

Rossana Barragán focuses on the subsequent periods of silver mining and refining in Potosí. In the seventeenth century, production in the silver mines decreased. Consequently, the mita changed from corvée labour to a payment in cash, to be paid to the mine and refining-mill operators. The trajectory followed by the Spanish state was still coercive, but now capital had replaced labour. When, in the 1730s, mining activities were re-intensified, some mitayos started to combine the unfree labour they had to perform during their “turn” with self-employed ore refining, working as so-called kajchas. As Barragán explains the mitayos, mingas, and kajchas were often one and the same person, who combined a wide variety of labour relations varying from unfree tributary to free wage work to self-employment.

Startled by this new development, the mine operators asked the Spanish Crown for a new allocation of labour under the mita. Barragán shows how lengthy discussions brought to the surface differences in interests and views regarding the desirability of coerced labour in favour of one specific interest group: the Spanish mine operators. These differences manifested themselves among the different levels of state administration in Potosí, Lima, Seville, and Madrid. It would take the Napoleonic occupation of Spain and the establishment of a National Assembly to abolish the mita. Here, a state-led system of coerced labour was finally abolished by a representative body installed by the French occupying state, mirroring the development of shifts in labour relations through the state as conqueror, only this time in the metropolis.

In his contribution “The Labour Recruitment of Local Inhabitants as Rōmusha in Japanese-Occupied South East Asia”, Takuma Melber analyses a relatively short period compared with the other articles. The political change in focus was more one of the ruler than of the system, since Japanese colonial rule directly replaced that of the Dutch. In order to build the necessary infrastructure in the South East Asian territories, the Japanese governors first hired workers. When workers failed to commit themselves in sufficient numbers, coercion was applied. The corresponding shift in labour relations was thus, mainly, from hired labour for non-market institutions to slavery. This article points out that during the immediate pre-war situation and during the war itself, the Japanese occupation caused South East Asian economies to become isolated from the world market. This resulted in unemployment and a shift by peasant smallholders away from cash crops to food production. When recruitment was coerced, those who had to join the infrastructural projects worked as tributary slaves. Those who could avoid forced labour by committing themselves to paramilitary work can be regarded as doing obligatory work for the polity. They could thus be employed side by side on the same project, and being able to opt for the less coerced mode could, literally, make a difference between life and death.

Lest the impression arise that the choice between coercion or capital and between performing the activities oneself or outsourcing them was something related only to early periods of state formation, many more modern states came to face the same issues in colonial contexts, and often chose approaches based on coercion, even if, at the same time, these very same states had come to rely on taxation and capital-intensive methods in the metropolis. To some extent, in colonial contexts they came to face a challenge similar to that of the early modern period, i.e. how to extract resources from societies with a low degree of monetization and commercialization. Colonial authorities, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, were often caught in a low-income cycle: to be able to invest in infrastructure, they needed customs revenues, which could be obtained only through some form of commercialization, for which it was necessary to invest in infrastructure, etc. To break this deadlock, they resorted to forced labour and corvée labour, either for commercial agriculture or for infrastructural work.Footnote 25

THE STATE AS DIRECT AND INDIRECT EMPLOYER

Direct as well as indirect, i.e. outsourced, employment in the service of the state in periods after consolidation of power often caused changes in labour relations, as various articles in this Special Issue show. In her contribution “Political Changes and Shifts in Labour Relations in Mozambique, 1820s–1920s”, Filipa Ribeiro da Silva shows how the Portuguese state, forced by the supranational power of the Conference of Berlin (1884–1885), had to occupy the colonial territories over which it wanted to gain rights. The Portuguese decided to employ an instrument they had used more often during their colonial history: outsourcing. Since the sixteenth century, various forms of outsourcing were in place: there was the Prazos da Coroa, a system of land tenure that had taken the form of chieftaincies in Mozambique; mining, agriculture, and trade was developed through outsourcing; but also, management of trade routes between Mozambique and Goa and in the Atlantic had been under private management. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, the newly gained areas of central and northern Mozambique that had been outsourced to two main companies chartered by the state were vaster than any area ever before. Moreover, the companies were authorized to issue their own regulations, their own currency, and establish their own police force. Not only the scale and the state-like functions of these companies were unprecedented; for the first time, private enterprises were encouraged to subjugate African leaders, enrol the African population and, thus, recruit, allocate, and control labour in the African continent itself. Sometimes, this co-optation of African leaders was voluntary, sometimes coerced. To give this change a legal basis and a moral justification, a new labour code was established that determined that all men “fit to work” had the moral obligation to do so and that through work Africans could “civilize themselves”.

In the areas commanded by the companies, labour relations that used to be predominantly reciprocal and tributary, with a small share of free and unfree (often slave) labour for the market, became more commodified, as the companies forced men into (often unfree forms of) wage labour and women into reciprocal, subsistence labour.

In her article “Grammar of Difference? The Dutch Colonial State, Labour Policies, and Social Norms on Work and Gender, c.1800–1940”, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk explores similarities and dissimilarities between the efforts of the Dutch state in the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies during the first half of the nineteenth century to enhance the industriousness of the population. Whereas in the Netherlands, these efforts served primarily to combat poverty, through the establishment of peat colonies where people on poor relief had to work, in the Netherlands Indies, the Cultivation System, established in 1830, was an instrument to increase the surplus generated by the colonial economy. This difference notwithstanding, the peat colonies in the Netherlands and the Cultivation System in the Netherlands Indies shared a common emphasis on industriousness as the key to advancement, and were indeed conceived and implemented by one and the same person, General Johannes van den Bosch (1780–1844). The Cultivation System relied principally on coercion to enhance the industriousness of Javanese peasants, requiring them to set aside part of their land to produce cash crops such as coffee, sugar, and indigo for the Dutch authorities. In practice, the work in the Dutch peat colonies also came to resemble tributary labour, from 1859 onwards solely for the Dutch state as owner of the colonies.

Fernando Mendiola’s article “The Role of Unfree Labour in Capitalist Development: Spain and Its Empire, Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Centuries” looks at the continuity of unfree labour in spite of political change.Footnote 26 The phases under observation here are the late Spanish colonial empire, and the periods of liberal parliamentarism, civil war, Fascist dictatorship, and parliamentary democracy up until the present.

The cases considered include slavery on Cuban sugar plantations and – in more limited scope – on the island of Bioko (Fernando Pó) off the coast of Equatorial Guinea; prison labour, obligatory labour in infrastructure, and military service; the prisoners of war in the Spanish concentration camps until 1945; and the recent indentured migrant labour working either in Spain or abroad in subcontracting companies. Overall, Mendiola notes that – within the ensemble unfree labour relations – slavery played a central role in the periods of the liberal revolution and the colonial empire, whereas during the period of liberal parliamentarism we see a shift to tributary labour for the state. These forms of unfree labour prevailed in the colonies, whereas in the metropolis unfree labour diminished until the period of civil war and fascist dictatorship. The Spanish state condoned slavery in the nineteenth century, but actively promoted convict labour, with varying degrees of legitimization. In his analysis, Mendiola argues that unfree labour served the purpose of capital accumulation, and that private enterprises and the state profited in various ways from these labour obligations.

Erdem Kabadayı’s contribution “Working for the State in the Urban Economies of Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica: From Empire to Nation State, 1840s–1940s” examines public service employment at the city level in the mid-nineteenth century Ottoman empire and in the nation states of Turkey and Greece, which emerged after the disintegration of the empire and the accompanying population exchanges of the 1920s. His findings are based on a comparison of three cities, of which two are in modern-day Turkey (Bursa, Ankara) and one in Greece (Salonica). As public service employment in the mid-nineteenth century was organized to a large extent at the neighbourhood level, he finds that the degree of ethnic and religious segregation between neighbourhoods in these cities had a strong impact on the religious and ethnic profile of public service sector employment. In cities with a high degree of segregation, like Salonica, or, to a lesser extent, Bursa, non-Muslims were well represented, whereas in Ankara, where the degree of segregation was much lower, Muslims clearly enjoyed comparative advantages in entering public service employment, something that Kabadayı relates to the dominant position of Islam in what was, officially, a multi-ethnic empire. After the population exchanges of the 1920s and the emergence of the nation states of Greece and Turkey, public service employment in the three cities came to reflect the ethnic and religious profile of the respective countries in a more direct manner.

These examples, as well as the other cases from the literature, can provide us with some clues as to the regularities and the issues involved in the choice between the various options the state had: to choose the capital or coercive trajectory (or a combination of both) and to perform the extractive activities with its own personnel and organizations, or to outsource them. To start with, it is obvious that the degree of monetization of a society plays a crucial role: although taxes can be, and often are, levied in kind, a low degree of commercialization and monetization generally appears to enhance the attractiveness of resorting to mobilization and the coercive extraction of labour and other resources, something already emphasized by Tilly as well.Footnote 27 Or, perhaps, this causality should be framed somewhat differently: monetization and commercialization allow for resource extraction based on taxation which would not otherwise have belonged to the range of possible options. The difference is one that revolves around assumptions on the expected pattern – do states resort to coercion when they cannot tax, or do states resort to coercion by default unless there happens to be an opportunity to tax? Certainly, from our modern point of view, we tend generally to expect taxation to be the default behaviour and coercion the explanandum, but the resort to coercion almost across the board in colonial situations by states relying on taxation in the metropolis does cast some doubt on such assumptions.

A second observation is that war and war-like situations tend to favour the use of coercion in recruiting and allocating labour to accomplish state tasks. This is true not only for military and military-auxiliary labour, where it is easier to explain, but also for infrastructural and industrial work not directly related to the military effort, as we see in Melber’s contribution on the Rōmusha in the Japanese empire during World War II, and as Mendiola has documented for the Spanish Civil War. Examples of war-like situations in which the same mechanisms appear to be at play outside of the scope of this volume include Soviet industrialization in the 1930sFootnote 28 as well as colonial contexts of subjugation of one nation by another.

THE STATE AS ARBITER AND MEDIATOR

Over time, in many Western states the capacity of the state as arbiter, mediator, and provider of social protection became more important, while military conquest receded. Paralleling the vast increase in the reach of the state within society, which involved more direct government employment, state-building moved away from the single focus on organizing the extraction of resources to a much wider mission, geared towards fostering welfare and economic development as well as human capital formation. The rise of complex legal systems, higher levels of education, and the availability of communication and information technologies enabled the state to enhance its roles. Intertwined with these efforts were what we have referred to as “labour ideologies”, i.e. belief systems, norms and values as well as ideals and aspirations relating to work and labour relations and informing policy choices.Footnote 29 These can be religiously, politically, or ethnically inspired, or, as is more often the case in today’s world, derived from economic theory or interpretations thereof. What is essential to the issues we are looking at in this volume is that these “ideologies” shape policymaking; indeed, they underlie some of the basic tenets of contemporaneous social systems, as in the case of the modern welfare state, based on the idea that certain sections of the population ought, by common effort, to be relieved of the necessity to work.

As Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk shows in her contribution to this volume, poor relief in the early nineteenth-century Netherlands was still based on the formula “who does not work, shall not eat”, as epitomized by the peat colonies founded by Johannes van den Bosch. But, in the course of the century, labour ideologies changed. The idea of the male breadwinner gained foothold, and child and women’s labour protection laws increasingly aimed to exclude women from the labour process and encourage an exclusive role for women in household work. Although postulated as universal values, attitudes and policies towards women’s labour in the colonies differed – indeed, Javanese women were seen as industrious and their contribution to the work of the household in farming and, notably, cash-crop farming as essential within the framework of the Cultivation System. Only much later, in the early twentieth century, did some of the ideas long in vigour in the metropolis, trickle down to the colonial context, but they never really came to have an impact on female labour participation, as economic considerations continued to have the upper hand in policy decisions. Borrowing a term from Stoler and Cooper, Van Nederveen Meerkerk refers to a “Grammar of Difference”, combining different norms in metropole and periphery regarding one and the same issue and leading to different labour relations for women in both areas.

Religiously inspired labour ideologies appear to have caused the gender-specific patterns of public service employment as described by Erdem Kabadayı for the 1920s urban centres of Bursa and Ankara in the newly born Turkish republic. The influence of Islam minimalized female public service employment, and indeed all employment in these three cities, particularly if compared to the cities of Salonica and Athens in the recently created Greek national state. A further example of gendered labour ideologies is provided by Takuma Melber, who refers to opinions raised in Japan during World War II that resisted the replacement of men in factories by women until it became absolutely imperative due to the erosion of the industrial workforce by military mobilization, because it conflicted with existing ideals of women as mothers and souls of the household.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the role of the state in shaping labour relations became even greater. Not only did the state evolve to become one of the largest employers in any society, in both western and eastern Europe it also built up a welfare state that exonerated a substantial part of the population from the duty to work, particularly through the introduction of retirement pensions and general, obligatory schooling.Footnote 30 In western Europe this was complemented by unemployment benefits for those involuntarily left out of the labour market, and in eastern Europe by policies of ensuring (and requiring) full employment for people of working age.Footnote 31

The contributions by Max Koch, “The Role of the State in Employment and Welfare Regulation: Sweden in the European Context”, and Raquel Varela, “State Policies Towards Precarious Work: Employment and Unemployment in Contemporary Portugal”, trace the development of the welfare state in Sweden and Portugal and the labour ideologies that accompanied it. Over time, a shift can be observed from “targeted” social welfare to a more universal approach and then back again as neo-liberal policies of deregulation and flexibilization started to spread from the 1990s. Koch’s contribution takes up the conceptualization of the state’s functions as employer and arbiter for twentieth-century Sweden and compares the Social Democratic period from the 1940s to the 1990s with the subsequent more deregulatory phase after Sweden joined the European Union in 1995. In a detailed view of the perspective of arbitration, he sees the state as “an object of agency of the sociopolitical coalition that creates and recreates it” and as an actor, “structured and structuring at the same time”. As such, he points to the three related fields of activity of capitalist states: ensuring property rights through legislation and adjudication, redistribution by taxation and welfare administration, and arbitration by temporarily harmonizing conflicting group interests and creating consensus. In the particular setting of Sweden’s relatively late membership of the EU, while policy designs and ideas emerged from new supranational agents and institutions and the accumulation of capital increasingly became a transnational process, the state remained important as a participant and actor in international regulation. Internally, in the deregulatory process, state actions towards the labour force became less visible, since much disciplining, regulating, and supporting was imparted to the “entrepreneurial employee”, which, as Max Koch perceptively remarks, resulted in a much improved “economy of power” compared with the earlier period of Social Democratic and top-down state impact, when collectively organized and class-aware workers prevailed.

Raquel Varela’s contribution focuses on the same period as that of Max Koch. Both countries joined the European Union at a relatively late stage (Portugal in 1986, Sweden in 1995), and the basic socioeconomic conditions were similar, though standards of living were higher in Sweden. But while Max Koch more directly links up with EU participation and supranational policy ideals and ideas, Raquel Varela concentrates on the implementation of labour policies that practically reinstated the ideal of the “right to work” instituted in the Portuguese constitution after the Carnation Revolution in 1974. She argues that in attenuating the effects of labour precarity and unemployment, the state acted as a direct participant in the labour market, functioning as both employer and mediator. In her view, welfare policies intended to address social inequalities and to promote reintegration into the labour market led instead to increased job insecurity and were closely related to the deregulation of employment. Moreover, deregulation did not imply less, but increased state intervention in the economy, since, for instance, there has been no reduction in the state’s role as a direct employer – in fact, the number of people employed by the state has increased. In Varela’s view, the state actively promoted a policy of cushioning the effects of deregulation, with the aim of maintaining the competitiveness of the Portuguese economy.

SHIFTS IN LABOUR RELATIONS AND THE STATE

What have we learned from the investigations in this issue into the role of the state as a causal factor in effecting historical shifts in labour relations? Firstly, relative to the “physiology” of states, we have found that trajectories of state formation matter. Particularly for states on a coercion-intensive trajectory, the link between state action and shifts in labour relations is evident, for example in early modern Muscovy and Russia, where geopolitical competition and forward expansion was accompanied by the emergence of, and increase in, tributary labour relations. Similarly, along the capital-intensive trajectory, state formation and the military recruitment it entails has been a factor in the rise of military labour markets, and therefore shifts to commodified labour relations. The best example here is, probably, the Dutch Republic, which attracted sailors to man its fleet from a hinterland far beyond its own borders.Footnote 32

It has also become clear from the contributions to this volume that there is by no means a one-to-one relationship to trajectories of state formation and the reliance on capital or coercion in mobilizing the resources and recruiting the labour required to carry out the tasks deemed essential for the functioning of the state. In fact, most states relied on a mix of capital and coercion, of monetary and coercive-administrative means, to accomplish their tasks. They also often outsourced part of their resource-extractive activities, thereby relying heavily on the instrument of co-optation. Particularly in the border areas of the larger land-based territorial empires, such as China’s and Russia’s, or rapidly expanding overseas empires, such as Spain’s in the early modern period or Portugal’s in the late nineteenth century, co-optation was a formidable instrument to deal with the constant challenge of neighbouring nomadic and semi-nomadic polities. In fact, more than anything, states appear surprisingly rational in choosing between capital and coercion and between outsourcing and co-optation or performing the activities themselves. States also appear to be flexible, switching between instruments over time, depending on the circumstances of the period and the challenges faced. The best-documented example here is that of the Chinese empire, which, in the course of the second millennium ad, switched back and forth several times between reliance on capital and coercion in military recruitment.

This should serve as a powerful reminder that there is no such thing as a fixed trajectory over time in the shifts in labour relations as effected by state formation. This is important because, on the face of it, shifts in labour relations appear to provide evidence of such a unilinear trajectory over time, from unfree to free labour. On the basis of our findings in this volume, we argue that this appearance is the manifestation of a causal link for which we have found evidence, i.e. between the degree of monetization of a society and the likelihood that states choose to rely on monetary instruments, rather than tributary obligations, to mobilize resources and labour. As most societies for which we have evidence have moved in the direction of greater monetization over the past 500 years or so, this tends to factor out tributary solutions over time, creating the appearance of a trend towards free rather than unfree labour. Crucial evidence to the contrary, though, is provided by that of the Chinese state during the transition from the Song to the Yuan, as well as by the readiness of colonial states, heavily reliant on capital in the metropolis, to resort to the use of coercion and tributary labour obligations in the periphery when confronted with societies with a low degree of monetization.

This brings us to the state in its capacity of a conqueror. We have found the state, in this role, to have been a causal factor in effecting shifts in labour relations. As conquerors, states can adapt existing forms of labour relations, as Spain did with the mita in Charcas. They can impose their own models, which can involve abrupt shifts in labour relations, as in the case of the Manchu conquest of China and the introduction of the banner system that accompanied it, or, vice versa, the incorporation of nomadic tribes into the Russian empire and the ensuing imposition of tributary labour relations. But we have also seen how states impose models other than their own. Some of the colonial states, for example, relied on capital at home and coercion in the colonies, like the Portuguese and the Spanish in Mozambique and Charcas, respectively. The imposition of the Cultivation System in the Netherlands Indies by the Dutch colonial state, as described by Van Nederveen Meerkerk, represented a shift in labour relations as part of such a two-tier model of state policy. A shift, moreover, that had repercussions not only in the periphery, but also in the centre itself, as the surplus generated by the exploitative Cultivation System in the colonies accommodated the rise of the male breadwinner model, relegating women to the sphere of domestic labour. In a similar vein, but with the opposite effect, conquest by the Japanese empire during World War II resulted in women joining the labour force in Japan to replace the men who had been mobilized into the army. Thus, conquest involves shifts in labour relations not only in the conquered territories, but also often, although not necessarily so, in the heartlands of the states concerned.

As states expand their reach, their impact on labour relations also increases, both in their capacity as arbiters or mediators, and as direct participants. To start with the latter, over time, states have become the single most important, and in some cases only, employer, and this makes them major “trendsetters” in labour relations, monopolizing certain sectors of the labour market and determining levels of remuneration and contractual standards. Most importantly, though, states have come to deeply affect labour relations in their roles of arbiters, legislators, and mediators. The example of the Ottoman empire and its ideology of Turkification and Islamification, leading to a drastically changed ethno-religious and gender makeup of the public sector, shows how the state as employer – even if it were a crumbling empire – could heavily influence labour relations. Modern states are driven in this respect by a powerful mixture of considerations related to their need to carry out the tasks essential for their functioning and the labour ideologies inspiring the models they aspire to implement. Such labour ideologies have been responsible for some of the most far-reaching shifts in labour relations seen over the past 200 years, notably the rise of the welfare state, based on the fundamental premise that a certain part of the population ought, by common effort, to be set free of the obligation to work, because of its inability to work, as a reward for past efforts, or in order to allow them to acquire the necessary skills to effectively participate in the labour process in the future.

A final development that also ought to be seen as the expression of certain labour ideologies is that states increasingly submit themselves to the arbitration or regulation of supranational bodies, whether within the framework of structures such as the European Union or as members of organizations such as the United Nations or the International Labour Organization. In her contribution to this volume, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk describes how, in the 1920s, the International Labour Organization put increasing pressure on the Dutch colonial state to introduce labour protection for women and children in the colonies. Finally, in their contributions to this volume Max Koch and Raquel Varela link deregulation within the framework of the European Union to a shift in labour relations that has played out in Europe over the past two decades, away from a system based primarily on employment, collective bargaining, and inclusive social welfare to a more entrepreneurial model based on self-employment, individual risk-aversion schemes, and a concomitant greater “precarity” in labour relations. What should be stressed, though, is that this rise and subsequent decline of the welfare state is a largely Western story. For many states in the Global South economic development, providing social security and support, and labour regulation and protection are still very much goals to be achieved and policies to be implemented.

Appendix: Taxonomy and Definitions of Labour Relations of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations

Since all articles in this volume refer to the core analytical tool of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, for the convenience of the reader we present here the entire taxonomy with the essential definitions. For an unabridged version of the definitions, including examples and methodological guidelines, see Karin Hofmeester et al., “The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500–2000: Background, Set-Up, Taxonomy, and Applications”, available at http://hdl.handle.net/10622/4OGRAD, last accessed 17 June 2016.

Figure 1 Taxonomy of Labour Relations.

Definitions of Labour Relations

Non-working:

1. Cannot work or cannot be expected to work: those who cannot work, because they are too young (≤6 years), too old (≥75 years),Footnote 33 disabled, or are studying.

2. Affluent: those who are so prosperous that they do not need to work for a living (rentiers, etc.), and consequently actually do not work.

3. Unemployed: those wanting to work but who cannot find employment.

Working:

Reciprocal labour:

Persons who provide labour for other members of the same household and/or community.

4a. Leading household producers: heads of (mostly) self-sufficient households (these include family-based and non-kin-based forms).

4b. Household kin producers: subordinate kin, including spouses (men and women) and children of the above heads of households, who perform productive work for that household.

5. Household kin non-producers: subordinate kin, including spouses (men and women) and children of heads of households, who perform reproductive work for the household.

6. Reciprocal household servants and slaves: subordinate non-kin (men, women, and children) contributing to the maintenance of (mostly) self-sufficient households.

7. Community-based redistributive labourers: persons who perform tasks for the local community in exchange for communally provided remuneration in kind.

Tributary labour:

Persons who are obliged to work for the polity (often the state, though it could also be a feudal or religious authority).

8. Obligatory labourers: those who have to work for the polity, and are remunerated mainly in kind.

9. Indentured tributary labourers: those contracted to work as unfree labourers for the polity for a specific period of time to pay off a debt or fine to that same polity.

10. Tributary serfs: those working for the polity because they are bound to its soil and bound to provide specified tasks.

11. Tributary slaves: those who are owned by and work for the polity indefinitely.

Commodified labour:

Work done on the basis of market exchange in which labour is “commodified”, i.e. where the worker or the products of his work are sold.

For the market, private employment:

12a. Self-employed leading producers: those who produce goods or services for the market with fewer than three employees, possibly in cooperation with

12b. Self-employed kin producers: household members including spouses and children who work together with self-employed leading producers who produce for the market.

13. Employers: those who produce goods or services for market institutions by employing more than three labourers.

13.1Employers who employ free wage earners.

13.2Employers who employ indentured labourers.

13.3Employers who employ serfs.

13.4Employers who employ slaves.

14. Market wage earners: wage earners (including the temporarily unemployed) who produce commodities or services for the market in exchange mainly for monetary remuneration.

14.1Sharecropping wage earners: remuneration is a fixed share of total output.

14.2Piece-rate wage earners: remuneration at piece rates.

14.3Time-rate wage earners: remuneration at time rates.

-

14.4 Cooperative subcontracting workers at piece rates.

15. Indentured labourers for the market: those contracted to work as unfree labourers for an employer for a specific period of time to pay off a private debt.

16. Serfs working for the market: those bound to the soil and bound to provide specified tasks.

17. Slaves who produce for the market: those owned by their employers (masters).

17.1Slaves working directly for their proprietor.

17.2Slaves for hire.

For non-market institutions:

18. Wage earners employed by non-market institutions (that may or may not produce for the market), such as the state, state-owned companies, the Church, or production cooperatives.

18.1Sharecropping wage earners.

18.2Piece-rate wage earners: remuneration at piece rates.

18.3Time-rate wage earners: remuneration at time rates.