Article contents

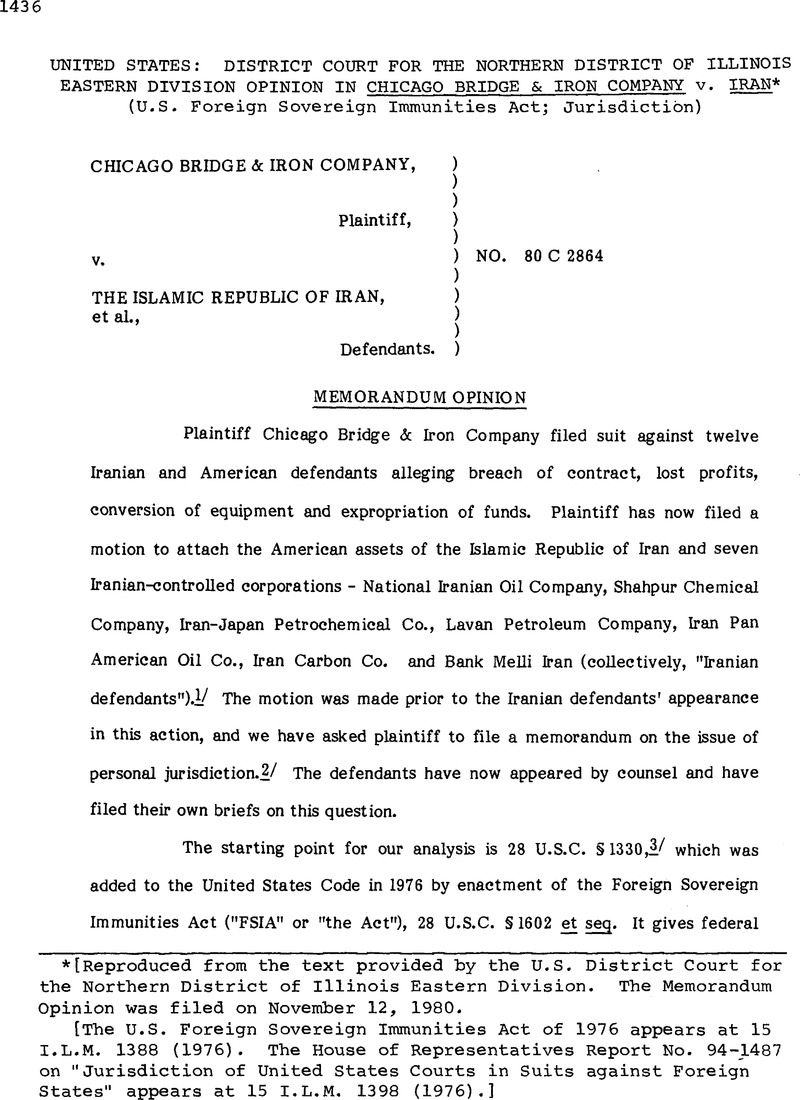

United States: District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division Opinion in Chicago Bridge & Iron Company v. Iran*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1980

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division. The MemorandumOpinion was filed on November 12, 1980.

[The U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 appears at 15I.L.M. 1388 (1976). The House of Representatives Report No. 94-1487 on “Jurisdiction of United States Courts in Suits against ForeignStates” appears at 15 I.L.M. 1398 (1976).]

References

1/ Plaintiff does not seek to attach the assets of two nongovernmental Iranian defendants, Norm Engineering Company and Farbal Co.

2/ While personal jurisdiction is generally waivable and can only be raised by the parties, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 ties personaljurisdiction to the substantive question of sovereign immunity. See p. 2 of textinfra. Sovereign immunity is, in fact, given jurisdictional status for both subjectmatter and personal jurisdictional purposes. International Association of Machinistsand Aerospace Workers v. OPEC, 477 F. Supp. 553, 565 (CD. Cal. 1979).Since it is the duty of a court to scrutinize continually its power to act, Warner v.Territory of Hawaii, 206 F.2d 851, 852 (9th Cir. 1953), it is not inappropriate for usto examine sua sponte the existence of jurisdiction, both subject matter andpersonal, to the extent they are intertwined.

3/ 28 U.S.C. § 1330, “Actions against foreign states,” provides:(a) The district courts shall have original jurisdiction without regard to amount in controversy of any nonjury civil actionagainst a foreign state as defined in section 1603(a) of thistitle as to any claim for relief in personam with respect towhich the foreign state is not entitled to immunity eitherunder sections 1605-1607 of this title or under any applicableinternational agreement. (b) Personal jurisdiction over a foreign state shall exist as toevery claim for relief over which the district courts havejurisdiction under subsection (a) where service has been madeunder section 1608 of this title. (c) For purposes of subsection (b), an appearance by a foreignstate does not confer personal jurisdiction with respect to anyclaim for relief not arising out of any transaction or occurrenceenumerated in sections 1605-1607 of this title. AddedPub.L. 94-583 § 2(a), Oct. 21, 1976, 90 Stat. 2891.

4/ 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(1) states:

(a) A foreign state shall not be immune from the jurisdictionof courts of the United States or of the States in any case—(1) in which the foreign state has waived its immunityeither explicitly or by implication, notwithstanding any withdrawalof the waiver which the foreign state may purport toeffect except in accordance with the terms of the waiver;

5/ Justice Brennan observed, “Once we have rejected the jurisdictionalframework created in Pennoyer v. Neff, I see no reason to rest jurisdiction on a fictional outgrowth of that system such as the existence of a consent statute,express or implied.” 433 U.S. at 227.

6/ See also, R. Leflar, American Conflicts Law § 24A, at 43 (3d ed.1977):The [Shaffer] decision proves beyond question that old jurisdictional dogma is not sacred. If century-old law on in remjurisdiction can be changed, so can other rules that are believed to operate unfairly.

7/ /Some courts have decided, for example, that prejudgment attachmentis not covered by the Treaty's waiver of sovereign immunity provision. Seediscussion at p. 5 supra.

8/ /Remarkably, plaintiff cites this exact language in the Verlindendecision, out of context, and with no indication that Judge Weinfeld criticized this “literalist” approach. Plaintiff's Supplemental Memorandum at p. 6.

9/ H.R. Rep. No. 1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 7, reprinted at [1976] U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News. 6604, 6605; Kahale Vega, “Immunity andJurisdiction: Toward a Uniform Body of Law in Actions Against Foreign States,” 18 Columbia J. of Transnational Law 211, 212, 218-19 and note 40 (1979).

10/ / 592 F.2d 673 (2d Cir. 1979). The Court of Appeals applied the same reasoning:

PETCO [subsidiary of plaintiff] is a Bahamian corporation.Though a subsidiary of NEPCO [plaintiff], it was a separatecorporate entity, and we will not here “pierce the corporateveil” in favor of those who created that veil. The cancellationof the contracts between NOC [defendant] and PETCO, andthe overcharge on the charters, had a direct effect on PETCOas a party to those contracts, but not in the United States.

Similarly, while there was an admitted effect on NEPCO, anAmerican company, that effect can only be deemed indirect,through NEPCOls relations with PETCO and Antco [subsidiaryof plaintiff NEPCO], whose dealings with NOC were entirelyoutside the United States….The appellants claim that the Libyan government and NOCwere aware that the refineries in the Bahamas were being usedprimarily to channel oil into the United States. Appellants also contend that the Libyan oil embargo was expressly aimedat affecting the United States. Even if these allegations aretrue, they do not fulfill the “minimum contacts” requirement of International Shoe, and thus cannot reach the level of“direct” effects described in the statute. 592 F.2d at 676-677 (citation omitted).

- 1

- Cited by